Religion in Azerbaijan

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Persecution |

Religion in Azerbaijan (2010 est.)

Note: religious affiliation for the majority of Azerbaijanis is largely nominal, percentages for actual practicing adherents are probably much lower.[1]

The main religion in Azerbaijan is Islam, though Azerbaijan is the most secular country in the Muslim world.[2] Estimates include 96.9% (CIA, 2010)[1] and 99.2% (Pew Research Center, 2006)[3] of the population identifying as Muslim. Most are adherents of Shia Islam (approximately 85%[4]), with a minority (15%) being Sunni, differences traditionally have not been defined sharply.[1][5] Most Shi'a are adherents of orthodox Ithna Ashari school of Shi'a Islam. Following many decades of Soviet atheist policy, religious affiliation is nominal in Azerbaijan and Muslim identity tends to be based more on culture and ethnicity than religion. Traditionally villages around Baku and Lenkoran region are considered stronghold of Shi'ism. In some northern regions, populated by Dagestani (Lezghian) people, Sunni Islam is dominant. Folk Islam is widely practiced but there is little evidence of an organized Sufi movement.[citation needed]

The rest of the population adheres to other faiths or are non-religious, although they are not officially represented.[1] Other traditional religions or beliefs that are followed by many in the country are the Armenian Apostolic Church (in Nagorno-Karabakh), the Russian Orthodox Church, and various other Christian denominations.

Like all other post-Soviet states formerly ruled by the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan is a secular state; article 48 of its Constitution ensures the liberty of worship, to choose any faith, or to not practice any religion, and to express one's view on the religion. The law of the Republic of Azerbaijan (1992) "On freedom of faith" ensures the right of any human being to determine and express his view on religion and to execute this right. However, a 1996 law states that foreigners have freedom of conscience, but are denied the right to "carry out religious propaganda", i.e., to preach, under the threat of fines or deportation.[6] According to paragraphs 1-3 of Article 18 of the Constitution the religion acts separately from the government, each religion is equal before the law and the propaganda of religions, abating human personality and contradicting to the principles of humanism is prohibited. At the same time the state system of education is also secular.

Islam

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Until recently Islam in Azerbaijan was relatively nominal. Although the vast majority of Azerbaijanis identified themselves as Muslims, surveys in the late Soviet and early post-Soviet era generally found that less than a quarter of those who considered themselves Muslims "had even a basic understanding of the pillars of Islam", according to researchers Emil Souleimanov and Maya Ehrmann.[7] According to a survey conducted in 2000, fewer than 7 percent of respondents considered themselves "firm believers," while just 18 percent confessed observance of salat (ritual prayer, one of the pillars of Islam).[8] Thus, for many Azerbaijanis, Islam tended toward a more ethnic/nationalistic identity than a purely religious one.[7]

An estimated four fifths of Muslims in Azerbaijan are Shi'as of the Twelver branch. The remainder are Sunnis belonging to the Hanafi branch and inhabit primarily the northern and western areas of the republic.[7] Folk Islam is widely practiced but there is little evidence of an organized Sufi movement.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union all religious organizations fell into depression and split into pieces while the Religious Organization of Transcaucasia Muslims headed by akhund Allahshukur Pashazade elected the Sheikh ul-Islam in 1980 intensified its operation and tried to spread its influence to the entire Caucasus under the name of the Caucasus Muslims Department. The measures to implement these attempts were undertaken at the tenth session of the Caucasus Muslims held in Baku in 1998. The opening of CMD representations in Georgia and Dagestan was one of the significant steps in this field.

The chair of CMD ensures the consequent contacts with Islamic organizations and manages to establish close religious relations with neighbor Muslim countries. To date CMD fulfills the religious needs of the Islamic communities of Azerbaijan, oversees the proper fulfillment of the rituals (in accordance with Sharia), progresses in training religious workers through the Islamic University of Baku, founded in 1991 and is responsible for all religious events occurring in the country. The faculty of theology of the State University of Baku has been training Islam and theology scientists since 1992.

Through the years of independence the worshipping of holies strengthened in Azerbaijan and the new holy places were set up along with old ones. Bakhailism created its own assembly and expanded yearly.

The relations of the state-religion are regulated by the State Committee for the Work with Religious Associations of Azerbaijan established by the decree of President Heydar Aliyev in 2001.

More recently, some Azerbaijani youths have been drawn increasingly to Islam.[9][failed verification] Additionally, some young women in Azerbaijan have decided to dress in Islamic attire despite the risks associated including being rebuked by university personnel for wearing the hijab.[10]

-

Nowruz in Azerbaijan.

Bahá'í

The Bahá'í Faith in Azerbaijan crosses a complex history of regional changes. Before 1850, followers of the predecessor religion Bábism were established in Nakhichevan.[11] By the early 20th century, the Bahá'í community, now centered in Baku, numbered perhaps 2000 individuals and several Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assemblies[12] had facilitated the favorable attention of local and regional,[11] and international[13] leaders of thought as well as long standing leading figures in the religion.[14] However under Soviet rule the Bahá'í community was almost ended[15] though it was immediately reactivated as perestroika loosened controls on religions[12] and re-elected its own National Spiritual Assembly in 1992.[16] The modern Bahá'í population of Azerbaijan, centered in Baku, may have regained its peak from the oppression of the Soviet period of about 2000 people, today with more than 80% converts[17] although the community in Nakhichevan, where it all began, is still seriously harassed and oppressed.[18]

Christianity

The Christian religion began to be spread in Azerbaijan by means of the Caucasus Albania in the first years of the new era in times of Christ's apostles.[19] Christianity is represented by Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Protestantism as well as a number of minority communities in Azerbaijan.

Christians, who are estimated to number between 280,000-450,000 (3.1%-4.8%)[20] are mostly Russian and Georgian Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic (almost all Armenians live in the break-away region of Nagorno-Karabakh). There is also a small ethnic Azerbaijani Protestant community, numbering around 5,000, mostly from Muslim backgrounds.[21][22]

Eastern Orthodox Church

Orthodoxy is currently represented in Azerbaijan by the Russian and Georgian Orthodox churches. The Russian Orthodox Churches are grouped in the Eparchy of Baku and the Caspian region.

Azerbaijan also has eleven Molokan communities related to the old rituals of Orthodoxy. These communities do not have any church; their dogmas are fixed in a special book of rituals. They oppose the church hierarchy which has a special power.

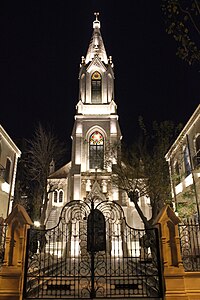

Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church

Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church[23] (Azerbaijani: Müqəddəs Qriqori kilsəsi, Armenian: Սուրբ Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչի Եկեղեցի) was built in 1871.[19] In 1869 Baku military governor Mikhail Petrovich Kolyubakin allotted land for the building of the church.The building was designed by Carl Gippius, brother of famous artist Otto Gustavovich Gippius (Yevstafiyevich) and architect of Baku city and the governorate. Carl Gippius's first work was the St Charles Church in Tallinn and second was Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church in Baku.He dedicated most of his life to construction of churches. In 1903 a library and school were built in the courtyard of the church. It survived through the Soviet state atheist policies of the 1920s and 1930s when all but one Armenian church in Baku were destroyed.[24][circular reference] In 2002 the church was transferred to the Presidential Library, which is located nearby, and now houses its archive.[25]

Albanian-Udi Church

Approximately 6,000 of the 10,000 people of the Udi ethnic community live in Azerbaijan including 4,400 people residing in Nij village, Qabala district.[26]

The Udis who resided on the territory of the Caspian sea shore, later accepted Christianity and spread this religion in the Caucasus Albania. The church of Kish (the Kish village of Shaki district) is one of the major examples of this cultural heritage.[26]

Catholic Church

There is a tiny Catholic community in Baku and surroundings, with less than a thousand members.

The Vatican Foreign Minister Giovanni Lajolo visited Baku on May 19, 2006. During the visit that lasted until May 25, he met with President Ilham Aliyev and chairman of the Caucasus Clerical Office, Sheikh Allahshukur Pashazada to discuss ties between Azerbaijan and the Vatican.[27]

Giovanni Lajolo made the following statements: "We are satisfied with the level of friendly communications between Azerbaijan and Vatican". "Azerbaijan really is a place of merge of religions and cultures. We highly estimate tolerance existing here. And we are very glad with intensive development of Azerbaijan. Vatican is interested in expansion of relations with Azerbaijan, and the purpose of my visit to Baku consists in carrying out of exchange by opinions on the further development of our ties."[28]

Baku's Catholic church was demolished in the Stalin era but a new one, started in September 2005, was opened in summer 2007.

Zoroastrianism

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The history of Zoroastrianism in Azerbaijan goes back to the first millennium BC. Together with the other territories of the Persian Empire, Azerbaijan remained a predominantly Zoroastrian state until the Arab invasion in the 7th century. The name Azerbaijan means the "Land of The Eternal Fire" in Middle Persian, a name that is said to have a direct link with Zoroastrianism.[29] Today the religion, culture, and traditions of Zoroastrianism remains highly respected in Azerbaijan, and Novruz continues to be the main holiday in the country. Zoroastrianism has left a deep mark in the history of Azerbaijan. Traces of the religion are still visible in Ramana, Khinalyg, and Yanar Dag.

Zoroastrianism in Azerbaijan has been tied not to survival of the ancient religion in the area, but a more recent arrival of the Parsi Zoroastrians coming from the British India, such as from Sindh and the Punjabi city of Multan at the time of the discovery of oil in Baku and the need for expert labor in the 1880s. Fire Temple of Baku was constructed for their use at the site of an ancient fire temple utilizing the naturally burning gas and oil on the ground. The structure a chartaqi is a standard fire temple of the Zoroastrians for thousands of years.c.

Judaism

There are three separate communities of Jews (Mountain Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Georgian Jews) in Azerbaijan, who total almost 16,000 combined. Of them, 11,000 are Mountain Jews, with concentrations of 6,000 in Baku and 4,000 in Quba, 4,300 are Ashkenazi Jews, most of whom live in Baku and Sumqayit, and 700 are Georgian Jews. There are three synagogues in Baku and a few in the provinces. Sheikh-ul-Islam Allahshukur Pashazade has donated US$40,000 for construction of Jewish House in Baku in 2000. There is also a Jewish village called Qırmızı Qəsəbə.

Hinduism

Hinduism in Azerbaijan has been tied to cultural diffusion on the Silk Road. In the Middle Ages, Hindu traders visited present-day Azerbaijan for Silk Road trade. The area was traversed by Hindu traders coming mostly from Multan and Sindh (Pakistan). The Hindus also have the Fire Temple of Baku. Today there are over 400-500 Hindus in Azerbaijan.

Older religions

Very little is known about pre-Christian and pre-Islam Azerbaijani mythology; sources are mostly Hellenic historians like Strabo and based on archeological evidence. Strabo names the gods of the sun, the sky, and above all, the moon.

Multiculturalism in Azerbaijan

There are more than 20 public places of Ukrainians , Meskhetian Turks, Tatars, Lacquers, Russians, Lezgins, Slavs, Georgians, Kurds, Ingiloy people, Talysh people, Avars, Europeans and Mountain Jews, Georgian Jews, Germans and Greeks only in Baku. According to information of State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations of Azerbaijan Republic there are 1802 Mosques, 5 Orthodox, 1 Catholic, 4 Georgian Catholic, 6 synagogues and other places of worship in Azerbaijan. Population consists of 96% Muslims, 4% Christians and representatives of other religions. Red Village of Guba has been home to Jews since the 13th century with their famous language, specific customs and traditions. There are 2 schools for Jews children, 7 Jewish communities and 2 synagogues.[30]

Government vouch for equality of rights and liberties of everyone, irrespective of race, nationality, religion, language, sex, origin, financial position, occupation, political convictions, membership in political parties, trade unions and other public organizations at Constitusion of Azerbaijan.[31] (Article 25, 44)

The multinational, multicultural and religious affairs of the State counsel services of Azerbaijan was created in February 2014. Baku International Multiculturalism Center was established based on decree of Azerbaijani President on May 15, 2014.

Aliyev declared that 2016 is called “Year of Multiculturalism” based on decree in 2016.[32]

Freedom of religion

The constitution of Azerbaijan provides for freedom of religion, and the law does not allow religious activities to be interfered with unless they endanger public order. Cases of anti-Semitism in Azerbaijan are rare.

The 2004 U.S. Department of State report on Human Rights in Azerbaijan noted some instances in which freedom of religion was violated, such as interference with the Juma Mosque due to the political activism of its Imam. All religious organizations are required to register with the government, and groups such as Baptists, Jehovah's Witnesses, and members of the Assemblies of God continue to be denied religious registration.[33] The official website of Jehovah's Witnesses has documented a number of acts of religious intolerance being committed by the Azerbaijan government against members of Jehovah's Witnesses.[34]

As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh war, mosques in the Nagorno-Karabakh region have been abandoned, and Armenian churches in Azerbaijan have likewise been inactive or damaged in the fighting.[35]

The position of the governmental authorities towards Islam is controversial. Men who grow beards more than normal are often viewed with suspicion by the authorities, for fear of the propagation of Wahhabism.[9] Despite the government's denial of the matter, the Azerbaijani police drew criticism from lawyers for infringing the rights of observant Muslims.[9]

However the 2009 Religion Law requires the compulsory re-registration of all religious groups.[36] The overwhelming majority of religious groups that have been granted re-registration are Muslim. Hundreds of others are still waiting to hear from the authorities.[36]

See also

- Irreligion in Azerbaijan

- State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations of Azerbaijan Republic

- Religion by country

References

- ^ a b c d "Middle East :: Azerbaijan — The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Islam and Secularism: the Azerbaijani experience and its reflection in France". PR Web. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ "Interactive Data Table: World Muslim Population by Country". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ http://files.preslib.az/projects/remz/pdf_en/atr_din.pdf

- ^ Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan - Presidential Library - Religion

- ^ Corley, Felix (November 1, 2005). "AZERBAIJAN: Selective obstruction of foreign religious workers". Forum 18. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- ^ a b c Souleimanov, Emil; Ehrmann, Maya (Fall 2013). "The Rise of Militant Salafism in Azerbaijan and Its Regional Implications". Middle East Policy Council. XX (3). Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Anar Valiyev, "Azerbaijan: Islam in a Post-Soviet Republic," Meria, 9, no. 4 (December 2005), accessed June 20, 2012, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (dead link). - ^ a b c ISN Editors. "Articles / Security Watch / ISN". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Spero NewsHeadscarves provoke controversy in Azerbaijan". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (2007-02-21), "The Baha'is of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {2/3}", Caucaz.com, archived from the original on 2007-10-30

- ^ a b "Baha'i Faith History in Azerbaijan". National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ Stendardo, Luigi (1985-01-30). Leo Tolstoy and the Bahá'í Faith. London, UK: George Ronald Publisher Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85398-215-9. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Bahá'í World Centre. pp. 797–800. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". The Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 05 (3). Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ Hassall, Graham. "Notes on Research on National Spiritual Assemblies". Research notes. Asia Pacific Bahá'í Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (2007-03-20), "The Baha'is of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {3/3}", Caucaz.com

- ^ U.S. State Department (2006-09-15). "International Religious Freedom Report 2006- Azerbaijan". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan". www.azerbaijan.az. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ^ "Global Christianity". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "5,000 Azerbaijanis adopted Christianity" (in Russian). Day.az. 7 July 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Christian Missionaries Becoming Active in Azerbaijan" (in Azerbaijani). Tehran Radio. 19 June 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Armenian Church of St Gregory the Illuminator in Baku, Azerbaijan". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ^ Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church, Baku

- ^ "Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine ::: Fountains Square: Looking Back in History". Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ^ a b "RELIGIONS IN PRESENT AZERBAIJAN". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-06-01. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ The Korea Times Azerbaijan Cultural Week Hits South Korea

- ^ Nielsen, Jørgen S.; Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibasi, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas (12 October 2012). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, Volume 4. ISBN 978-9004225213.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan" (PDF).

- ^ "Official Page of Azerbaijani Multiculturalism".

- ^ "Azerbaijan". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Highlights of the Past Year". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "2004 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Azerbaijan". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b Forum 18 News Service. "Forum 18 Archive: AZERBAIJAN: Communities to be forced to begin re-registration again? - 8 June 2011". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

- Albanian-Udi Church reestablished

- Vatican in Baku

- North American Azerbaijani Network - an organization of over 90 groups and churches committed to seeing the Azerbaijani people reached with the gospel of Jesus Christ.

- Charles, Robia: "Religiosity in Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan" in the Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 20