Thai art

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

... |

Traditional Thai art is primarily composed of Buddhist art and scenes from the Indian epics. Traditional Thai sculpture almost exclusively depicts images of the Buddha, being very similar with the other styles from Southeast Asia, such as Khmer. Traditional Thai paintings usually consist of book illustrations, and painted ornamentation of buildings such as palaces and temples. Thai art was influenced by indigenous civilizations of the Mon and Khmer. By the Sukothai and Ayutthaya period, thai had developed into its own unique style and was later further influenced by the other Asian styles, mostly by Sri Lankan and Chinese. Thai sculpture and painting, and the royal courts provided patronage, erecting temples and other religious shrines as acts of merit or to commemorate important events.

History

Prehistory

Prior to the southwards migration of the Thai peoples from Yunnan in the 10th century, mainland Southeast Asia had been a home to various indigenous communities for thousands of years. The discovery of Homo erectus fossils such as Lampang man is an example of archaic hominids. The remains were first discovered during excavations in Lampang Province. The finds have been dated from roughly 1,000,000–500,000 years ago in the Pleistocene. Stone artefacts dating to 40,000 years ago have been recovered from, e.g., Tham Lod rockshelter in Mae Hong Son and Lang Rongrien Rockshelter in Krabi, peninsular Thailand.[1] The archaeological data between 18,000–3,000 years ago primarily derive from cave and rock shelter sites, and are associated with Hoabinhian foragers.[2]

-

Vessel in the form of a water buffalo; 2300 BC; ceramic; height: 18 cm (73⁄32 in.)

-

Bowl; from Ban Chiang site; painted ceramic; height: 32 cm, diameter: 31 cm

-

Jar; 300 BC-400 AD; painted earthenware; Honolulu Academy of Arts (Hawaii, USA)

Sukhothai period

The Sukhothai period began in the 14th century in the Sukhothai Kingdom. Buddha images of the Sukhothai period are elegant, with sinuous bodies and slender, oval faces. This style emphasized the spiritual aspect of the Buddha, by omitting many small anatomical details. The effect was enhanced by the common practice of casting images in metal rather than carving them. This period saw the introduction of the "walking Buddha" pose.[citation needed]

Sukhothai artists tried to follow the canonical defining marks of a Buddha, as they are set out in ancient Pali texts:

- Skin so smooth that dust cannot stick to it

- Legs like a deer

- Thighs like a banyan tree

- Shoulders as massive as an elephant's head

- Arms round like an elephant's trunk, and long enough to touch the knees

- Hands like lotuses about to bloom

- Fingertips turned back like petals

- head like an egg

- Hair like scorpion stingers

- Chin like a mango stone

- Nose like a parrot's beak

- Earlobes lengthened by the earrings of royalty

- Eyelashes like a cow's

- Eyebrows like drawn bows

Sukhothai also produced a large quantity of glazed ceramics in the Sawankhalok style, which were traded throughout Southeast Asia.[citation needed]

-

The ruins of Wat Mahathat, Sukhothai Historical Park

-

Phra Achana, Wat Si Chum, Big Buddha image, Sukhothai

Ayutthaya period

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2011) |

The surviving art from this period was primarily executed in stone, characterised by juxtaposed rows of Buddha figures. In the middle period, Sukhothai influence dominated, with large bronze or brick and stucco Buddha images, as well as decorations of gold leaf in free-form designs on a lacquered background. The late period was more elaborate, with Buddha images in royal attire, set on decorative bases.

-

Statue of Buddha Shakyamuni; 14th-15th century; copper alloy; 73.03 x 53.34 x 25.4 cm (283⁄4 x 21 x 10 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

Bangkok period

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2011) |

This period is characterized by the further development of the Ayutthaya style, rather than by more great innovation. One important element was the Krom Chang Sip Mu (Organization of the Ten Crafts), founded in Ayutthaya, which was responsible for improving the skills of the country's craftsmen. Paintings from the mid-19th century show the influence of Western art.

-

Statue of a monk; 19th century; gilt copper alloy; 75.25 x 38.74 x 47.31 cm (295⁄8 x 151⁄4 x 185⁄8 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Buddha Shakyamuni in the Parileyaka forest attended by animals; late 19th century; gilt copper alloy with lacquer; 115.57 x 51.44 x 47.63 cm (451⁄2 x 201⁄4 x 183⁄4 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Contemporary

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2011) |

Modern painting in the western sense started late in Thailand, with Professor Silpa Bhirasri and the establishment of Silpakorn University, but Thai artists are now expressing themselves in a variety of media such as installations, photographs, prints, video art and performance art.[citation needed]

Painting

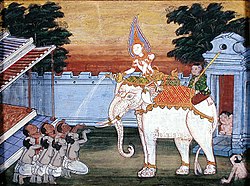

Traditional Thai paintings showed subjects in two dimensions without perspective. The size of each element in the picture reflected its degree of importance. The primary technique of composition is that of apportioning areas: the main elements are isolated from each other by space transformers. This eliminated the intermediate ground, which would otherwise imply perspective. Perspective was introduced only as a result of Western influence in the mid-19th century. Monk artist Khrua In Khong is well-known as the first artist to introduce linear perspective to Thai traditional art.

The most frequent narrative subjects for paintings were or are: the Jataka stories, episodes from the life of the Buddha, the Buddhist heavens and hells, themes derived from the Thai versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, not to mention scenes of daily life. Some of the scenes are influenced by Thai folklore instead of following strict Buddhist iconography.

-

A page of the Phra Malai Manuscript; opaque watercolor and ink on paper; covers: gilded and lacquered paper; c. 1860–1880; 13.97 x 68.26 x 6.35 cm (51⁄2 x 267⁄8 x 21⁄2 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art

-

A page of the Phra Malai Manuscript; opaque watercolor and ink on paper; covers: gilded and lacquered paper; c. 1860–1880; 13.97 x 68.26 x 6.35 cm (51⁄2 x 267⁄8 x 21⁄2 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art

-

Vessantara Jataka, Chapter 8 (The Royal Children); 1920-1940 AD; paint on cloth; height: 52.5 cm (20.6 in), width: 66.5 cm (26.1 in); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

-

A page of a Thai manuscript from the Wellcome Collection (London) that represents the monk Phra Malai converses with Indra in heaven

Sculpture

Thai sculpture almost exclusively depicts images of the Buddha, being very similar with the other styles from Southeast Asia, such as Khmer. Most of the sculptures depict Buddha. An exception is the dvarapala.

-

Lintel depicting the Hindu god Nārāyaṇa sleeping upon the serpent Śeṣa in the middle of the Milky Ocean; around 12th century; obtained from the Ku Suan Taeng Temple (Ban Mai Chaiyaphot District, Buri Ram Province); Bangkok National Museum

-

Guardian figure (dvarapala); 15th century; glazed stonewear; Harn Museum of Art (Florida, USA)

Architecture

Architecture is the preeminent medium of the country's cultural legacy and reflects both the challenges of living in Thailand's sometimes extreme climate as well as, historically, the importance of architecture to the Thai people's sense of community and religious beliefs. Influenced by the architectural traditions of many of Thailand's neighbors, it has also developed significant regional variation within its vernacular and religious buildings.

Thai temples

Buddhist temples in Thailand are known as "wats", from the Pāḷi vāṭa, meaning an enclosure. A temple has an enclosing wall that divides it from the secular world. Wat architecture has seen many changes in Thailand in the course of history. Although there are many differences in layout and style, they all adhere to the same principles.

-

The kamphaeng kaeo (crystal wall) surrounding the ubosot at Wat Ratchabophit in Bangkok

Traditional Thai houses

As the phrase "Thai stilt house" suggests, one universal aspect of Thailand's traditional architecture is the elevation of its buildings on stilts, most commonly to around head height. The area beneath the house is used for storage, crafts, lounging in the daytime, and sometimes for livestock. The houses were raised due to heavy flooding during certain parts of the year, and in more ancient times, predators. Thai building and living habits are often based on superstitious and religious beliefs. Many other considerations such as locally available materials, climate, and agriculture have a lot to do with the style.

-

The traditional Thai house at King Rama II Memorial Park

-

Chulalongkorn Traditional Thai house is a central Thai traditional style house mixed with decoration

-

Traditional Thai-style stilt house on a canal near the Chao Phraya River in Bangkok

Ceramics

Ceramics in Thailand were mostly used for domestic purposes such as holding food and water. Thai ceramics in the pattern of nature and animals were popular between the 11th and 13th centuries.

Types

| Name | Period | Notes | Example image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ban Chiang | 3400 BCE - 200 CE | spoons, beads, jars, vessel, pots, and vases. Some decorated with simple geometric patterns. Unglazed – red clay, some red on buff painted [3] |

|

| Ban Kao | 2000 BCE – 500 BCE [5] | jars, vessel, pots, vase, and tripods. Decorated with simple geometric patterns. Ban Kao's ceramics are thinner when compared to Ban Chiang. Glazed – red and black clay | |

| Mon people | Hariphunchai, 200 CE – 1000 CE | figurines, votive tablets and building decorations. Unglazed – red clay |

|

| Sukhothai ware | Sukhothai, 14th century – 16th century | animal figurines, bowls, and boxes. Opaque or greenish glazed – creamy white slip – fine clay |

|

| Kalong ware | Sukhothai, 14th century – 16th century |

| |

| Sankampaeng ware | Sukhothai, 14th century – 16th century |

| |

| Sawankhalok ware | Sukhothai, 14th century – 16th century | animal figurines, bowls, and boxes. Opaque or greenish glazed – creamy white slip – fine clay |

|

| Si Satchanalai ware | Sukhothai, 14th century – 16th century | animal figurines, bowls, and boxes. Opaque or greenish glazed – creamy white slip – fine clay |

|

| Ayutthaya | 17th century - 18th century | bowls, pedestal plates, roof tiles, and votive tablets. Enameled painted – creamy white slip – fine clay[4] | |

| Benjarong | Bangkok, 18th century - present | bowls, pedestal plates, roof tiles, and votive tablets. five colours, influenced from China |

|

| Lai Nam Thong | Bangkok, 19th century - present |

Shadow play

Shadow theatre in Thailand is called nang yai; in the south there is a tradition called nang talung.[5] Nang yai puppets are normally made of cowhide and rattan. Performances are normally accompanied by a combination of songs and chants. Performances in Thailand were temporarily suspended in 1960 due to a fire at the national theatre. Nang drama has influenced modern Thai cinema, including filmmakers like Cherd Songsri and Payut Ngaokrachang.[6]

-

A nang talung shadow puppet

-

A nang drama player and puppet

-

A shadow puppet that represents an aquatic fairy that seduces Hanuman; Museum of the Orient (Lisbon, Portugal)

See also

References

- ^ Anderson, D. 1990. Lang Rongrien Rockshelter: A Pleistocene–early Holocene Archaeological Site from Krabi, Southwestern Thailand. Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Lekenvall, Henrik. "Late Stone Age Communities in the Thai-Malay Peninsula". Journal of Indo-Pacific Archaeology 32 (2012): 78-86.

- ^ "Thai Ceramics: asia-art"

- ^ "Types of Ancient Ceramics: thailandceramicart” Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lian Lim, Siew (2013). "The Role of Shadow Puppetry in the Development of Phatthalung Province, Thailand" (PDF). siewlianlim.com. Southeast Asia Club Conference, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ Nang Yai Archived 2002-12-25 at the Wayback Machine from Mahidol University.

Further reading

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870993747.

- Piriya Krairiksh (Edited by Peter Sharrock; Translated by Narisa Chakrabongse; Photography Paisarn Piemmettawat) (2012). The Roots of Thai Art. Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 9786167339115.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Rama IX Art Museum Virtual museum of Thai contemporary artists. Listings of museums, galleries, exhibitions and venues. Contains muchinformation on Thai artists and art activities.

- Golden Triangle Art Introduction of contemporary art and artists living and working in Northern Thailand and Myanmar. Guide to art galleries, art News and exhibitions with focus on Chiang Mai.

- Thai Buddhist Art Thai Buddhist Art Website Project to Promote and play a part in the growth of the Thai Fine Art Community of Collectors and Aficionados. Representing a host of Thailand's Most Outstanding Artists.