Yorubaland

Yorubaland

Ilẹ̀ Yorùbá Southwest Nigeria, Western Nigeria, South and Central Benin, Central Togo and Ghana | |

|---|---|

Cultural region | |

| Nickname: Ilẹ̀ Káarò-Õjíire | |

Location of Yorubaland (green) in West Africa (white) | |

| Part of | |

| Earliest dated Ifẹ̀ artefact | 500 BCE |

| - Oyo Empire | 1400 |

| - British Colony | 1862 |

| - French Colony | 1872 |

| - Dahomey (Now Benin) | 1904 |

| - Nigeria | 1914 |

| Founded by | PYIG (Proto Yoruba-Itsekiri-Igala) |

| Regional capital | • Ilẹ̀-Ifẹ̀ (Cultural/Spiritual) • Ibadan (Political) • Lagos/Eko (Economic) |

| Former seat | • Oyo-Ile (Old Political) |

| Composed of | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Monarchies • Oba (King) • Ògbóni (Legislature) • Olóye (Chiefs) • Balógun (Generalissimo) • Baálẹ̀ (Village/Regional heads in Western Yorubaland) • Ọlọja (Village/Regional heads in Eastern Yorubaland) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 142,114 km2 (54,871 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,055 m (3,461 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −0.2 m (−0.7 ft) |

| Population (2015 estimate) | |

| • Total | ~ 55 million |

| • Density | 387/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| In Nigeria, Benin and Togo | |

| Demographics | |

| • Language | Yoruba |

| • Religion | Christianity, Islam, Yoruba religion |

| Time zone | WAT (Nigeria, Benin), GMT (Togo) |

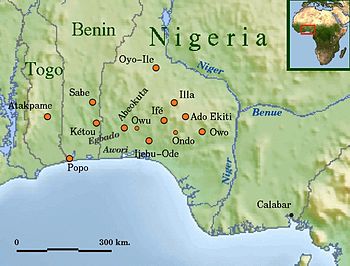

Yorubaland (Template:Lang-yo) is the cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern day countries of Nigeria, Togo and Benin, and covers a total land area of 142,114 km2 or about the same size as the combined land areas of Greece and Montenegro, of which 106,016 km2 (74.6%) lies within Nigeria, 18.9% in Benin, and the remaining 6.5% is in Togo. The geocultural space contains an estimated 55 million people, the overwhelming majority of this population being ethnic Yorubas.

Geography

Geophysically, Yorubaland spreads north from the Gulf of Guinea and west from the Niger River into Benin and Togo. In the northern section, Yorubaland begins in the suburbs just west of Lokoja and continues unbroken up to the Ogou River tributary of the Mono River in Togo, a distance of around 610 km. In the south, it begins in an area just west of the Benin river occupied by the Ilaje Yorubas and continues uninterrupted up to Porto Novo, a total distance of about 270 km as the crow flies. West of Porto Novo Gbe speakers begin to predominate. The northern section is thus more expansive than the southern coastal section.

The land is characterised by mangrove forests, estuaries and coastal plains in the south, which rise steadily northwards into rolling hills and a jagged highland region in the interior, commonly known as the Yorubaland plateau or Western upland. The highlands are pronounced in the Ekiti area of the region, especially around the Effon ridge and the Okemesi fold belt, which have heights in excess of 732m (2,400 ft) and are characterized by numerous waterfalls and springs such as Olumirin waterfall, Arinta waterfall, and Effon waterfall.[1][2] The highest elevation is found at the Idanre Inselberg Hills, which have heights in excess of 1,050 meters. In general, the landscape of the interior is undulating land with occasional inselbergs jutting out dramatically from the surrounding rolling landscape. Some include: Okeagbe hills: 790m, Olosunta in Ikere Ekiti: 690m, Shaki inselbergs, and Igbeti hill.

With coastal plains, southern lowlands, and interior highlands, Yorubaland has several large rivers and streams that crisscross the terrain.[1] These rivers flow in two general directions within the Yoruba country; southwards into the lagoons and creeks which empty into the Atlantic ocean, and northwards into the Niger river. The Osun River which empties into the Lekki Lagoon, the Ogun River which empties into the Lagos Lagoon, Mono River, Oba River, Owena river, Erinle River, Yewa River which discharges into the Badagry creek, Okpara River which drains into the Porto-Novo lagoon, Ouémé River, Ero river between Ekiti State and Kwara State, among numerous others. Others such as the Moshi river, Oshin and Oyi flow towards the Niger (north).

The Nigerian part of Yorubaland comprises today's Ọyọ, Ọṣun, Ogun, Kwara, Ondo, Ekiti, Lagos as well as parts of Kogi .[1] The Beninese portion consists of Ouémé department, Plateau Department, Collines Department, Tchaourou commune of Borgou Department, Bassila commune of Donga Department, Ouinhi and Zogbodomey commune of Zou Department, and Kandi commune of Alibori Department. The Togolese portions are the Ogou and Est-Mono prefectures in Plateaux Region, and the Tchamba prefecture in Centrale Region.

Vegetation and climate

The climate of Yorubaland varies from north to south. The southern, central and eastern portions of the territory is tropical high forest covered in thick verdant foliage and composed of many varieties of hardwood timber such as Milicia excelsa which is more commonly known locally as iroko, Antiaris africana, Terminalia superba which is known locally as afara, Entandrophragma or sapele, Lophira alata, Triplochiton scleroxylon (or obeche), Khaya grandifoliola (or African mahogany) and Symphonia globulifera amongst numerous other species. Some non-native species such as Tectona grandis (teak) and Gmelina arborea (pulp wood) have been introduced into the ecosystem and are being extensively grown in several large forest plantations. The ecosystem here forms the major section of the Nigerian lowland forest region, the broadest forested section of Nigeria.

The coastal section of this area features an area covered by swamp flats and dominated by such plants as mangroves and other stilt plants as well as palms, ferns and coconut trees on the beaches. This portion includes most of Ondo, Ekiti, Ogun, Osun, Lagos states and is characterised by generally high levels of precipitation defined by a double maxima (peak period); March–July and September–November. Annual rainfall in Okitipupa, for example, averages 1,900 mm.[3] The area is the center of a thriving cocoa, natural rubber, kola nut and oil palm production industry, as well as lucrative logging. Ondo, Ekiti and Osun states are the leading producers of cocoa in Nigeria,[4][5] while the southern portions of Ogun and Ondo states (Odigbo, Okitipupa and Irele) play host to large plantations of oil palm and rubber.

The northern and western portions of the region is characterized by tropical woodland savanna climate (Aw), with a single rainfall maxima. This area covers the northern two-thirds of Oyo, northwestern Ogun, Kwara, Kogi, Collines (Benin), northern half of Plateau department (Benin) and central Togo. Part of this region is derived savanna which was once covered in forest but has lost tree cover due to agricultural and other pressures on land. Annual rainfall here hovers between 1,100 and 1,500 mm. Annual precipitation in Ilorin for example is 1,220 mm.[6] Tree species here include the [[Blighia sapida]] more commonly known as ackee in English and ishin in Yoruba, and Parkia biglobosa which is the locust bean tree used in making iru or ogiri, a local cooking condiment.

The monsoon (rainy period) in both climatic zones is followed by a drier season characterized by northwest trade winds that bring the harmattan (cold dust-laden windstorms) that blow from the Sahara. They normally affect all areas except a small portion of the southern coast. Nonetheless, it has been reported that the harmattan has reached as far as Lagos in some years.

Administrative divisions

| Yorubaland | ||||||||

| Country | |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Area (km2) | Regional capital | Largest city | 2nd largest city | Map | |||

| Ekiti State | 6,353 | Ado Ekiti | Ado Ekiti | Ikere-Ekiti |

| |||

| Kogi State | 9,351 | Lokoja | Kabba | Isanlu | ||||

| Kwara State | 17,000 | Ilorin | Ilorin | Offa | ||||

| Lagos State | 3,345 | Ikeja | Alimosho | Ikorodu | ||||

| Ogun State | 16,762 | Abeokuta | Otta-Ijoko-Ifo | Abeokuta | ||||

| Ondo State | 15,500 | Akure | Akure | Ondo, Owo | ||||

| Osun State | 9,251 | Oshogbo | Oshogbo | Ile-Ife, Ilesha | ||||

| Oyo State | 28,454 | Ibadan | Ibadan | Ogbomosho | ||||

| Area = 106,016 km2 | ||||||||

| Country | | ||||||||

| Department | Area (km2) | Regional capital | Largest city | 2nd largest city | ||||

| Borgu (Shaworo) | 5,000 | ____ | Shaworo | Papane | ||||

| Collines | 12,440 | Savalou | Shabe | Idasa | ||||

| Donga (Bassila) | 5,661 | ____ | Bassila | Manigri | ||||

| Plateau | 3,264 | Sakete | Pobe | Ketu, Sakete | ||||

| Weme | 500 | Porto Novo | Porto Novo | Adjarra | ||||

| Area ≈ 26,865 km2 | ||||||||

| Country | | ||||||||

| Region | Area (km2) | Regional capital | Largest city | 2nd largest city | ||||

| Central (Chamba) | 3,149 | ____ | Kambole | Alejo | ||||

| Plateaux | 6,084 | Atakpame | Atakpame | Anié, Morita | ||||

| Area ≈ 9,233 km2 | Yorubaland Area ≈ 142,114 km2 | |||||||

Prehistory and oral tradition

Settlement

Oduduwa is regarded as the legendary progenitor of the Yoruba, and almost every Yoruba settlement traces its origin to princes of Ile-Ife in Osun State, Nigeria. As such, Ife can be regarded as the cultural and spiritual homeland of the Yoruba nation, both within and outside Nigeria. According to an Oyo account, Oduduwa was a Yoruba emissary; said to have come from the east, sometimes understood by some sources as the "vicinity" true east on the cardinal points, but more likely signifying the region of the Ekiti and Okun sub-communities in Yorubaland, Nigeria.[7] On the other hand, linguistic evidence seems to corroborate the fact that the eastern half of Yorubaland was settled at an earlier time in history than the western regions, as the Northwest and Southwest Yoruba dialects show more linguistic innovations than their central and eastern counterparts.[citation needed].

Pre-Civil War

Between 1100 and 1700, the Yoruba Kingdom of Ife experienced a golden age, part of which was a sort of artistic and ideological renaissance.[citation needed] It was then surpassed by the Oyo Empire as the dominant Yoruba military and political power between 1700 and 1900. Yoruba people generally feel a deep sense of culture and tradition that unifies and helps identify them.[citation needed] There are sixteen established kingdoms, states that are said to have been descendants of Oduduwa himself. The other sub-kingdoms and chiefdoms that exist are second order branches of the original sixteen kingdoms.

There are various groups and subgroups in Yorubaland based on the many distinct dialects of the Yoruba language, which although all mutually intelligible, have peculiar differences. The governments of these diverse people are quite intricate and each group and subgroup varies in their pattern of governance. In general, government begins at home with the immediate family. The next level is the extended family with its own head, an Olori-Ebi. A collection of distantly related extended families makes up a town. The individual chiefs that serve the towns as corporate entities, called Olóyès, are subject to the Baálès that rule over them. A collection of distantly related towns makes up a clan. A separate group of Oloyes are subject to the Oba that rules over an individual clan, and this Oba may himself be subject to another Oba, depending on the grade of the Obaship.

In this, government begins at home. The father of the family is considered the "head" and his first wife is the mother of the house. If her husband chooses to marry another wife, that wife must show proper respect to the first wife even if the first wife is chronologically younger. Children are taught to have respect for all those who are older than they are. This includes their parents, aunts, uncles, elder siblings, and cousins who they deal with every day. ... Any adult presumably has as much authority over a child as the child's parents do. All members of a particular clan live in the same compound and share family resources, rights, and possessions such as land

— Bascum 1969[8]

History

Government

Ife was surpassed by the Oyo Empire as the dominant Yoruba military and political power between 1600 CE and 1800 CE. The nearby kingdom of Benin was also a powerful force between 1300 and 1850 CE. Most of the city states were controlled by Obas, priestly monarchs, and councils made up of Oloyes, recognised leaders of royal, noble and, often, even common descent, who joined them in ruling over the kingdoms through a series of guilds and sects. Different states saw differing ratios of power between the kingship and the chiefs' council. Some, such as Oyo, had powerful, autocratic monarchs with almost total control, while in others such as the Ijebu city-states, the senatorial councils were supreme and the Ọba served as something of a figurehead. In all cases, however, Yoruba monarchs were subject to the continuing approval of their constituents as a matter of policy, and could be easily compelled to abdicate for demonstrating dictatorial tendencies or incompetence. The order to vacate the throne was usually communicated through an aroko or symbolic message, which usually took the form of parrot eggs delivered in a covered calabash bowl by the Ogboni senators. In most cases, the message would compel the Oba to take his own life, which he was bound by oath to do.

Civil War

Following a jihad (known as the Fulani War) led by Uthman Dan Fodio (1754–1817) and a rapid consolidation of the Hausa city-states of contemporary northern Nigeria, the Fulani Sokoto Caliphate annexed the buffer Nupe Kingdom and began to press southwards towards the Oyo Empire. Shortly after, they overran the Yoruba city of Ilorin and then sacked Ọyọ-Ile, the capital city of the Oyo Empire. Further attempts by the Sokoto Caliphate to expand southwards were checked by the Yoruba who had rallied to resist under the military leadership of the city-state of Ibadan, which rose from the old Oyo Empire, and of the Ijebu city-states.

However, the Oyo hegemony had been dealt a mortal blow. The other Yoruba city-states broke free of Oyo dominance, and subsequently became embroiled in a series of internecine wars, a period when millions of individuals were forcibly transported to the Americas and the Caribbean, eventually ending up in such countries as the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Brazil, Haiti and Venezuela, among others.

European colonization of the Yoruba

These wars weakened the Yoruba in their opposition to what was coming next; British military invasions. The military defeat at Imagbon of Ijebu forces by the British colonial army in 1892 ensured a tentative European settlement in Lagos, one which was gradually expanded by protectorate treaties. These treaties proved decisive in the eventual annexation of the rest of Yorubaland and, eventually, of southern Nigeria and the Cameroons.

In 1960, greater Yorubaland was subsumed into the Federal Republic of Nigeria.[9]

According to Yoruba historians, by the time the British came to colonize and subjugate Yorubaland first to itself and later to the Fulani of Northern Nigeria, the Yoruba were getting ready to recover from what is popularly known as the Yoruba Civil War. One of the lessons of the internecine Yoruba wars was the opening of Yorubaland to Fulani hegemony whose major interest was the imposition of sultanistic despotism on Old Oyo Ile and present-day Ilorin. The most visible consequence of this was the adding of almost one-fifth of Yorubaland from Offa to Old Oyo to Kabba to the then-Northern Nigeria of Lord Frederick Lugard and the subsequent subjugation of this portion of Yorubaland under the control of Fulani feudalism.[10]

Demographics

Yorubaland is one of the most populated ethnic homelands in Africa. It is also highly urbanized, holding 40% of settlements in Nigeria with over 100,000 people, although there is also a very large rural population like the rest of Africa. The regional population density is considerably high, at approximately 387 people in every square kilometer. This population density is not evenly distributed across the region, with values ranging from more than 140,000 people/km2 in certain districts of Lagos like Mushin, Ajeromi-Ifelodun, Shomolu, Agege and Isale Eko - which are among the world's densest, to 42,000 people/km2 in the urban city core of Ibadan. On a subregional level, the Ekiti, Osun, southern and central Ogun, Porto Novo and suburbs, Ibadan metro, Lagos, and the Akoko area of northern Ondo state are the vicinities with the higher population densities.

On the contrasting end of the spectrum, Ifelodun and Moro local government areas of central Kwara, with densities of about 80 people/km2, Ijebu east and Ogun Waterside local Government areas of eastern Ogun with densities of around 95 people/km2, Atisbo and Iwajowa LGAs in western Oyo (50 and 55 ppl/km2), as well as central Benin and Togolese Yorubaland have the lowest densities.

Typically, cities are laid out such that both the palace of the king or paramount chief and the central market are located in the city core. This area is immediately surrounded by the town itself, which is in turn surrounded by farmland and smaller villages. The larger settlements in Yorubaland tend to be nucleated in nature, with very high densities surrounded by agricultural areas of low density. Cities grow from the inside out. By definition the nearer a part of town is to the city core, the older it is, with the palace and the central market in the very center of town being the oldest establishments and the foundation of the city itself.

References

- ^ a b c Defence Language Institute, Curriculum Development Division: Yoruba Culture Orientation, 2008

- ^ "Taking a short road trip through Oke-Mesi Fold Belt (Part 1)". olokuta.blogspot.ca. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Okitipupa climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Okitipupa weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ http://www.fao.org/3/a-at586e.pdf

- ^ https://www.nigeriagalleria.com. "Ondo State of Nigeria:: Nigeria Information & Guide". www.nigeriagalleria.com. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ^ "Climate Ilorin: Temperature, Climograph, Climate table for Ilorin - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Article: Oduduwa, The Ancestor Of The Crowned Yoruba Kings Archived February 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ William R. Bascom:The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1969. page 42. ISBN 0-03-081249-6

- ^ Gat, Azar. "War in human civilization" Oxford University Press, 2006, pg 275.

- ^ Ishokan Yoruba Magazine, Volume III No. I, Page 7, 1996/1997