Alauddin Khalji

| Alauddin Khalji | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sultan Sikander - e- Sani | |||||

| File:Sultan Alauddin Khalji.jpg Sultan Alauddin Khalji | |||||

| Sultan of Delhi | |||||

| Reign | 19 July 1296–4 January 1316 | ||||

| Coronation | 21 October 1296 | ||||

| Predecessor | Jalaluddin Firuz Khalji | ||||

| Successor | Shihabuddin Omar | ||||

| Governor of Awadh | |||||

| Tenure | c. 1296–19 July 1296 | ||||

| Governor of Kara | |||||

| Tenure | c. 1291–1296 | ||||

| Predecessor | Malik Chajju | ||||

| Successor | ʿAlāʾ ul-Mulk | ||||

| Amir-i-Tuzuk | |||||

| Tenure | c. 1290–1291 | ||||

| Born | Ali Gurshasp c.1267 | ||||

| Died | 4 January 1316 (aged 48–49) Delhi, India | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Khalji dynasty | ||||

| Father | Shihabuddin Mas'ud | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Alaud-Dīn Khaljī (r. 1296–1316), born as Ali Gurshasp, was the emperor of the Khalji dynasty that ruled the Delhi Sultanate in the Indian subcontinent. Alauddin instituted a number of significant administrative changes, related to revenues, price controls, and society. He is noted for repulsing the Mongol invasions of India.

Alauddin was a nephew and a son-in-law of his predecessor Jalaluddin. When Jalaluddin became the Sultan of Delhi after deposing the Mamluks, Alauddin was given the position of Amir-i-Tuzuk (equivalent to master of ceremonies). Alauddin obtained the governorship of Kara in 1291 after suppressing a revolt against Jalaluddin, and the governorship of Awadh in 1296 after a profitable raid on Bhilsa. In 1296, Alauddin raided Devagiri, and acquired loot to stage a successful revolt against Jalaluddin. After killing Jalaluddin, he consolidated his power in Delhi, and subjugated Jalaluddin's sons in Multan.

Over the next few years, Alauddin successfully fended off the Mongol invasions from the Chagatai Khanate, at Jaran-Manjur (1297–1298), Sivistan (1298), Kili (1299), Delhi (1303), and Amroha (1305). In 1306, his forces achieved a decisive victory against the Mongols near the Ravi riverbank, and later ransacked the Mongol territories in present-day Afghanistan. The military commanders that successfully led his army against the Mongols include Zafar Khan, Ulugh Khan, and his slave-general Malik Kafur.

Alauddin conquered the kingdoms of Gujarat (raided in 1299 and annexed in 1304), Ranthambore (1301), Chittor (1303), Malwa (1305), Siwana (1308), and Jalore (1311). These victories ended several Hindu dynasties, including the Paramaras, the Vaghelas, the Chahamanas of Ranastambhapura and Jalore, the Rawal branch of the Guhilas, and possibly the Yajvapalas. His slave-general Malik Kafur led multiple campaigns to the south of the Vindhyas, obtaining a considerable amount of wealth from Devagiri (1308), Warangal (1310) and Dwarasamudra (1311). These victories forced the Yadava king Ramachandra, the Kakatiya king Prataparudra, and the Hoysala king Ballala III to become Alauddin's tributaries. Kafur also raided the Pandya kingdom (1311), obtaining much treasure and many elephants and horses.

At times, Alauddin exploited Muslim fanaticism against Hindu chieftains and the treatment of the zimmis. According to the later chronicler Barani, he rarely heeded to the orthodox ulema but believed "that the Hindu will never be submissive and obedient to the Musalman unless the Hindu is reduced to extreme poverty." He undertook measures to impoverish them and felt it was justified because he knew the Hindu chiefs and muqaddams led a luxurious life but didn't pay a jital in taxes. Under the Mamluks, Hindus were deprived of positions in higher bureaucracy. However, Amir Khusrau mentions a Hindu officer of his army despatched to repel the Mongols. In addition, many non-Muslims served in his army.

During the last years of his life, Alauddin suffered from an illness, and relied on Malik Kafur to handle the administration. After his death in 1316, Malik Kafur appointed Shihabuddin, son of Alauddin and his Hindu wife Jhatyapali, as a puppet monarch. However, his elder son Qutbuddin Mubarak Shah seized the power shortly after his death.

Early life

Contemporary chroniclers did not write much about Alauddin's childhood. According to the 16th/17th-century chronicler Haji-ud-Dabir, Alauddin was 34 years old when he started his march to Ranthambore (1300–1301). Assuming this is correct, Alauddin's birth can be dated to 1266–1267.[2] His original name was Ali Gurshasp. He was the eldest son of Shihabuddin Mas'ud, who was the elder brother of the Khalji dynasty's founder Sultan Jalaluddin. He had three brothers: Almas Beg (later Ulugh Khan), Qutlugh Tigin and Muhammad.[3]

Alauddin was brought up by Jalaluddin after Shihabuddin's death.[4] Both Alauddin and his younger brother Almas Beg married Jalaluddin's daughters. After Jalaluddin became the Sultan of Delhi, Alauddin was appointed as Amir-i-Tuzuk (equivalent to Master of ceremonies), while Almas Beg was given the post of Akhur-beg (equivalent to Master of the Horse).[5]

Marriage to Jalaluddin's daughter

Alauddin married Jalaluddin's daughter, Malika-i-Jahan, long before the Khalji revolution of 1290. The marriage, however, was not a happy one. Having suddenly become a princess after Jalaluddin's rise as a monarch, she was very arrogant and tried to dominate Alauddin. According to Haji-ud-Dabir, Alauddin married a second woman, named Mahru, who was the sister of Malik Sanjar alias Alp Khan.[6] Malika-i-Jahan was greatly infuriated by the fact that her husband had taken a second wife. According to Dabir, this was the main cause of misunderstanding between Alauddin and his first wife.[6] Once, while Alauddin and Mahru were together in a garden, Jalaluddin's daughter attacked Mahru out of jealousy. In response, Alauddin assaulted her. The incident was reported to Jalaluddin, but the Sultan did not take any action against Alauddin.[5] Alauddin was not on good terms with his mother-in-law either, who wielded great influence over the Sultan. According to the 16th-century historian Firishta, she warned Jalaluddin that Alauddin was planning to set up an independent kingdom in a remote part of the country. She kept a close watch on Alauddin, and encouraged her daughter's arrogant behavior towards him.[7]

Governor of Kara

In 1291, Alauddin played an important role in crushing a revolt by the governor of Kara Malik Chajju. As a result, Jalaluddin appointed him as the new governor of Kara in 1291.[5] Malik Chajju's former Amirs (subordinate nobles) at Kara considered Jalaluddin as a weak and ineffective ruler, and instigated Alauddin to usurp the throne of Delhi.[6] This, combined with his unhappy domestic life, made Alauddin determined to dethrone Jalaluddin.[4]

Conspiracy against Jalaluddin

While instigating Alauddin to revolt against Jalaluddin, Malik Chajju's supporters emphasized that he needed a lot of money to raise a large army and stage a successful coup: Malik Chajju's revolt had failed for want of resources.[6] To finance his plan to dethrone Jalaluddin, Alauddin decided to raid the neighbouring Hindu kingdoms. In 1293, he raided Bhilsa, a wealthy town in the Paramara kingdom of Malwa, which had been weakened by multiple invasions.[4] At Bhilsa, he came to know about the immense wealth of the southern Yadava kingdom in the Deccan region, as well as about the routes leading to their capital Devagiri. Therefore, he shrewdly surrendered the loot from Bhilsa to Jalaluddin to win the Sultan's confidence, while withholding the information on the Yadava kingdom.[8] A pleased Jalaluddin gave him the office of Ariz-i Mamalik (Minister of War), and also made him the governor of Awadh.[9] In addition, the Sultan granted Alauddin's request to use the revenue surplus for hiring additional troops.[10]

After years of planning and preparation, Alauddin successfully raided Devagiri in 1296. He left Devagiri with a huge amount of wealth, including precious metals, jewels, silk products, elephants, horses, and slaves.[11] When the news of Alauddin's success reached Jalaluddin, the Sultan came to Gwalior, hoping that Alauddin would present the loot to him there. However, Alauddin marched directly to Kara with all the wealth. Jalaluddin's advisors such as Ahmad Chap recommended intercepting Alauddin at Chanderi, but Jalaluddin had faith in his nephew. He returned to Delhi, believing that Alauddin would carry the wealth from Kara to Delhi. After reaching Kara, Alauddin sent a letter of apology to the Sultan, and expressed concern that his enemies may have poisoned the Sultan's mind against him during his absence. He requested a letter of pardon signed by the Sultan, which the Sultan immediately despatched through messengers. At Kara, Jalaluddin's messengers learned of Alauddin's military strength and of his plans to dethrone the Sultan. However, Alauddin detained them, and prevented them from communicating with the Sultan.[12]

Meanwhile, Alauddin's younger brother Almas Beg (later Ulugh Khan), who was married to a daughter of Jalaluddin, assured the Sultan of Alauddin's loyalty. He convinced Jalaluddin to visit Kara and meet Alauddin, saying that Alauddin would commit suicide out of guilt if the Sultan didn't pardon him personally. A gullible Jalaluddin set out for Kara with his army. After reaching close to Kara, he directed Ahmad Chap to take his main army to Kara by the land route, while he himself decided to cross the Ganges river with a smaller body of around 1,000 soldiers. On 20 July 1296, Alauddin had Jalaluddin killed after pretending to greet the Sultan, and declared himself the new king. Jalaluddin's companions were also killed, while Ahmad Chap's army retreated to Delhi.[13]

Ascension and march to Delhi

Alauddin, known as Ali Gurshasp until his ascension in July 1296, was formally proclaimed as the new king with the title Alauddunya wad Din Muhammad Shah-us Sultan at Kara. Meanwhile, the head of Jalaluddin was paraded on a spear in his camp before being sent to Awadh.[3] Over the next two days, Alauddin formed a provisional government at Kara. He promoted the existing Amirs to the rank of Maliks, and appointed his close friends as the new Amirs.[14]

At that time, there were heavy rains, and the Ganga and the Yamuna rivers were flooded. But Alauddin made preparations for a march to Delhi, and ordered his officers to recruit as many soldiers as possible, without fitness tests or background checks.[14] His objective was to cause a change in the general political opinion, by portraying himself as someone with huge public support.[15] To portray himself as a generous king, he ordered 5 manns of gold pieces to be shot from a manjaniq (catapult) at a crowd in Kara.[14]

One section of his army, led by himself and Nusrat Khan, marched to Delhi via Badaun and Baran (modern Bulandshahr). The other section, led by Zafar Khan, marched to Delhi via Koil (modern Aligarh).[14] As Alauddin marched to Delhi, the news spread in towns and villages that he was recruiting soldiers while distributing gold. Many people, from both military and non-military backgrounds, joined him. By the time he reached Badaun, he had a 56,000-strong cavalry and a 60,000-strong infantry.[14] At Baran, Alauddin was joined by seven powerful Jalaluddin's nobles who had earlier opposed him. These nobles were Tajul Mulk Kuchi, Malik Abaji Akhur-bek, Malik Amir Ali Diwana, Malik Usman Amir-akhur, Malik Amir Khan, Malik Umar Surkha and Malik Hiranmar. Alauddin gave each of them 30 to 50 manns of gold, and each of their soldiers 300 silver tankas (hammered coins).[15]

Alauddin's march to Delhi was interrupted by the flooding of the Yamuna river. Meanwhile, in Delhi, Jalaluddin's widow Malka-i-Jahan appointed her youngest son Qadr Khan as the new king with the title Ruknuddin Ibrahim, without consulting the nobles. This irked Arkali Khan, her elder son and the governor of Multan. When Malika-i-Jahan heard that Jalaluddin's nobles had joined Alauddin, she apologized to Arkali and offered him the throne, requesting him to march from Multan to Delhi. However, Arkali refused to come to her aid.[15]

Alauddin resumed his march to Delhi in the second week of October 1296, when the Yamuna river subsided. When he reached Siri, Ruknuddin led an army against him. However, a section of Ruknuddin's army defected to Alauddin at midnight.[15] A dejected Ruknuddin then retreated and escaped to Multan with his mother and the loyal nobles. Alauddin then entered the city, where a number of nobles and officials accepted his authority. On 21 October 1296, Alauddin was formally proclaimed as the Sultan in Delhi.[16]

Consolidation of power

Initially, Alauddin consolidated power by making generous grants and endowments, and appointing many people to the government positions.[17] He balanced the power between the officers appointed by the Mamluks, the ones appointed by Jalaluddin and his own appointees.[16] He also increased the strength of the Sultanate's army, and gifted every soldier the salary of a year and a half in cash. Of Alauddin's first year as the Sultan, chronicler Ziauddin Barani wrote that it was the happiest year that the people of Delhi had ever seen.[17]

At this time, Alauddin's could not exercise his authority over all of Jalaluddin's former territories. In the Punjab region, his authority was limited to the areas east of the Ravi river. The region beyond Lahore suffered from Mongol raids and Khokhar rebellions. Multan was controlled by Jalaluddin's son Arkali, who harboured the fugitives from Delhi.[17] In November 1296, Alauddin sent an army led by Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan to conquer Multan. On his orders, Nusrat Khan arrested, blinded and/or killed the surviving members of Jalaluddin's family.[18][19]

Shortly after the conquest of Multan, Alauddin appointed Nusrat Khan as his wazir (prime minister).[20] Having strengthened his control over Delhi, the Sultan started eliminating the officers that were not his own appointees.[21] In 1297,[22] the aristocrats (maliks), who had deserted Jalaluddin's family to join Alauddin, were arrested, blinded or killed. All their property, including the money earlier given to them by Alauddin, was confiscated. As a result of these confiscations, Nusrat Khan obtained a huge amount of cash for the royal treasury. Only three maliks from Jalaluddin's time were spared: Malik Qutbuddin Alavi, Malik Nasiruddin Rana, Malik Amir Jamal Khalji.[23] The rest of the older aristocrats were replaced with the new nobles, who were extremely loyal to Alauddin.[24]

Meanwhile, Ala-ul Mulk, who was Alauddin's governor at Kara, came to Delhi with all the officers, elephants and wealth that Alauddin had left at Kara. Alauddin appointed Ala-ul Mulk as the kotwal of Delhi and placed all the non-Turkic municipal employees under his charge.[21] Since Ala-ul Mulk had become very obese, the governorship of Kara was entrusted to Nusrat Khan, who had become unpopular in Delhi because of the confiscations.[24]

Mongol invasions and northern conquests, 1297–1306

In the winter of 1297, the Mongols led by a noyan of the Chagatai Khanate raided Punjab, advancing as far as Kasur. Alauddin's forces, led by Ulugh Khan, defeated the Mongols on 6 February 1298. According to Amir Khusrow, 20,000 Mongols were killed in the battle, and many more were killed in Delhi after being brought there as prisoners.[25] In 1298–99, another Mongol army (possibly Neguderi fugitives) invaded Sindh, and occupied the fort of Sivistan. This time, Alauddin's general Zafar Khan defeated the invaders, and recaptured the fort.[26][27]

In early 1299, Alauddin sent Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan to invade Gujarat, where the Vaghela king Karna offered a weak resistance. Alauddin's army plundered several towns including Somnath, where it desecrated the famous Hindu temple. The Delhi army also captured several people, including the Vaghela queen Kamala Devi and slave Malik Kafur, who later led Alauddin's southern campaigns.[28][29] During the army's return journey to Delhi, some of its Mongol soldiers staged an unsuccessful mutiny near Jalore, after the generals forcibly tried to extract a share of loot (khums) from them. Alauddin's administration meted out brutal punishments to the mutineers' families in Delhi, including killings of children in front of their mothers.[30] According to Ziauddin Barani, the practice of punishing wives and children for the crimes of men started with this incident in Delhi.[31]

In 1299, the Chagatai ruler Duwa sent a Mongol force led by Qutlugh Khwaja to conquer Delhi.[32] In the ensuing Battle of Kili, Alauddin personally led the Delhi forces, but his general Zafar Khan attacked the Mongols without waiting for his orders. Although Zafar Khan managed to inflict heavy casualties on the invaders, he and other soldiers in his unit were killed in the battle.[33] Qutlugh Khwaja was also seriously wounded, forcing the Mongols to retreat.[34]

In 1301, Alauddin ordered Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan to invade Ranthambore, whose king Hammiradeva had granted asylum to the leaders of the mutiny near Jalore. After Nusrat Khan was killed during the siege, Alauddin personally took charge of the siege operations, and conquered the fort in July 1301.[35] During the Ranthambore campaign, Alauddin faced three unsuccessful rebellions.[36] To suppress any future rebellions, he set up an intelligence and surveillance system, instituted a total prohibition in Delhi, established laws to prevent his nobles from networking with each other, and confiscated wealth from the general public.[37]

In the winter of 1302–1303, Alauddin dispatched an army to ransack the Kakatiya capital Warangal. Meanwhile, he himself led another army to conquer Chittor, the capital of the Guhila kingdom ruled by Ratnasimha.[38] Alauddin captured Chittor after an eight-month long siege.[39] According to his courtier Amir Khusrow, he ordered a massacre of 30,000 local Hindus after this conquest.[40] Some later legends state that Alauddin invaded Chittor to capture Ratnasimha's beautiful queen Padmini, but most modern historians have rejected the authenticity of these legends.[41]

While the imperial armies were busy in Chittor and Warangal campaigns, the Mongols launched another invasion of Delhi around August 1303.[42] Alauddin managed to reach Delhi before the invaders, but did not have enough time to prepare for a strong defence.[43][44] Meanwhile, the Warangal campaign was unsuccessful (because of heavy rains according to Ziauddin Barani), and the army had lost several men and its baggage. Neither this army, nor the reinforcements sent by Alauddin's provincial governors could enter the city because of the blockades set up by the Mongols.[45][46] Under these difficult circumstances, Alauddin took shelter in a heavily guarded camp at the under-construction Siri Fort. The Mongols engaged his forces in some minor conflicts, but neither army achieved a decisive victory. The invaders ransacked Delhi and its neighbourhoods, but ultimately decided to retreat after being unable to breach Siri.[47] The Mongol invasion of 1303 was one of the most serious invasions of India, and prompted Alauddin to take several steps to prevent its repeat. He strengthened the forts and the military presence along the Mongol routes to India.[48] He also implemented a series of economic reforms to ensure sufficient revenue inflows for maintaining a strong army.[49]

In 1304, Alauddin appears to have ordered a second invasion of Gujarat, which resulted in the annexation of the Vaghela kingdom to the Delhi Sultanate.[50] In 1305, he launched an invasion of Malwa in central India, which resulted in the defeat and death of the Paramara king Mahalakadeva.[51][52] The Yajvapala dynasty, which ruled the region to the north-east of Malwa, also appears to have fallen to Alauddin's invasion.[53]

In December 1305, the Mongols invaded India again. Instead of attacking the heavily guarded city of Delhi, the invaders proceeded south-east to the Gangetic plains along the Himalayan foothills. Alauddin's 30,000-strong cavalry, led by Malik Nayak, defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Amroha.[54][55] Many Mongols were taken captive and killed; the 16th-century historian Firishta claims that the heads (sir) of 8,000 Mongols were used to build the Siri Fort commissioned by Alauddin.[56]

In 1306, another Mongol army sent by Duwa advanced up to the Ravi River, ransacking the territories along the way. Alauddin's forces, led by Malik Kafur, decisively defeated the Mongols.[57] Duwa died next year, and after that the Mongols did not launch any further expeditions to India during Alauddin's reign. On the contrary, Alauddin's Dipalpur governor Malik Tughluq regularly raided the Mongol territories located in present-day Afghanistan.[58][59]

Marwar and southern campaigns, 1307–1313

Around 1308, Alauddin sent Malik Kafur to invade Devagiri, whose king Ramachandra had discontinued the tribute payments promised in 1296, and had granted asylum to the Vaghela king Karna at Baglana.[60] Kafur was supported by Alauddin's Gujarat governor Alp Khan, whose forces invaded Baglana, and captured Karna's daughter Devaladevi (later married to Alauddin's son Khizr Khan).[61] At Devagiri, Kafur achieved an easy victory, and Ramachandra agreed to become a lifelong vassal of Alauddin.[62]

Meanwhile, a section of Alauddin's army had been besieging the fort of Siwana in Marwar region unsuccessfully for several years.[63] In August–September 1308, Alauddin personally took charge of the siege operations in Siwana.[52] The Delhi army conquered the fort, and the defending ruler Sitaladeva was killed in November 1308.[64]

The plunder obtained from Devagiri prompted Alauddin to plan an invasion of the other southern kingdoms, which had accumulated a huge amount of wealth, having been shielded from the foreign armies that had ransacked northern India.[65] In late 1309, he sent Malik Kafur to ransack the Kakatiya capital Warangal. Helped by Ramachandra of Devagiri, Kafur entered the Kakatiya territory in January 1310, ransacking towns and villages on his way to Warangal.[66] After a month-long siege of Warangal, the Kakatiya king Prataparudra agreed to become a tributary of Alauddin, and surrendered a large amount of wealth (possibly including the Koh-i-Noor diamond) to the invaders.[67]

Meanwhile, after conquering Siwana, Alauddin had ordered his generals to subjugate other parts of Marwar, before returning to Delhi. The raids of his generals in Marwar led to their confrontations with Kanhadadeva, the Chahamana ruler of Jalore.[68] In 1311, Alauddin's general Malik Kamaluddin Gurg captured the Jalore fort after defeating and killing Kanhadadeva.[69]

During the siege of Warangal, Malik Kafur had learned about the wealth of the Hoysala and Pandya kingdoms located further south. After returning to Delhi, he took Alauddin's permission to lead an expedition there.[70] Kafur started his march from Delhi in November 1310,[71] and crossed Deccan in early 1311, supported by Alauddin's tributaries Ramachandra and Prataparudra.[72]

At this time, the Pandya kingdom was reeling under a war of succession between the two brothers Vira and Sundara, and taking advantage of this, the Hoysala king Ballala had invaded the Pandyan territory. When Ballala learned about Kafur's march, he hurried back to his capital Dwarasamudra.[73] However, he could not put up a strong resistance, and negotiated a truce after a short siege, agreeing to surrender his wealth and become a tributary of Alauddin.[74][75]

From Dwarasamudra, Malik Kafur marched to the Pandya kingdom, where he raided several towns. Both Vira and Sundara fled their headquarters, and thus, Kafur was unable to make them Alauddin's tributaries. Nevertheless, the Delhi army looted many treasures, elephants and horses.[76] The Delhi chronicler Ziauddin Barani described this seizure of wealth from Dwarasamudra and the Pandya kingdom as the greatest one since the Muslim capture of Delhi.[77]

During this campaign, the Mongol general Abachi had conspired to ally with the Pandyas, and as a result, Alauddin ordered him to be executed in Delhi. This, combined with their general grievances against Alauddin, led to resentment among Mongols who had settled in India after converting to Islam. A section of Mongol leaders plotted to kill Alauddin, but the conspiracy was discovered by Alauddin's agents. Alauddin then ordered a mass massacre of Mongols in his empire, which according to Barani, resulted in the death of 20,000 or 30,000 Mongols.[78]

Meanwhile, in Devagiri, after Ramachandra's death, his son tried to overthrow Alauddin's suzerainty. Malik Kafur invaded Devagiri again in 1313, defeated him, and became the governor of Devagiri.

Administrative changes

Alauddin was the most powerful ruler of his dynasty.[79][80] Unlike the previous rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, who had largely relied on the pre-existing administrative set-up, Alauddin undertook large-scale reforms.[81] After facing the Mongol invasions and several rebellions, he implemented several reforms to be able to maintain a large army and to weaken those capable of organizing a revolt against him.[82] Barani also attributes Alauddin's revenue reforms to the Sultan's desire to subjugate the Hindus by "depriving them of that wealth and property which fosters rebellion".[83] According to historian Satish Chandra, Alauddin's reforms were based on his conception of fear and control as the basis of good government as well as his military ambitions: the bulk of the measures were designed to centralise power in his hands and to support a large military.[84]

Some of Alauddin's land reforms were continued by his successors, and formed a basis of the agrarian reforms introduced by the later rulers such as Sher Shah Suri and Akbar.[85] However, his other regulations, including price control, were revoked by his son Qutbuddin Mubarak Shah a few months after his death.[86]

Revenue reforms

The countryside and agricultural production during Alauddin's time was controlled by the village headmen, the traditional Hindu authorities. He viewed their haughtiness and their direct and indirect resistance as the main difficulty affecting his reign. He also had to face talk of conspiracies at his court.[87]

After some initial conspiracies and Hindu revolts in rural areas during the early period of his reign, he struck the root of the problem by introducing reforms that also aimed at ensuring support of his army and food supply to his capital. He took away all landed properties of his courtiers and nobles and cancelled revenue assignments which were henceforth controlled by the central authorities. Henceforth, "everybody was busy earning with earning a living so that nobody could even think of rebellion". He also ordered "to supply some rules and regulations for grinding down the Hindus, and for depriving them of that wealth and property which fosters rebellion. The Hindu was to be reduced to be so reduced as to be unable to keep a horse to ride on, wear fine clothes, or to enjoy any luxuries of life."[87]

Alauddin brought a large tract of fertile land under the directly-governed crown territory, by eliminating iqta's, land grants and vassals in the Ganga-Yamuna Doab region.[88] He imposed a 50% kharaj tax on the agricultural produce in a substantial part of northern India: this was the maximum amount allowed by the Hanafi school of Islam, which was dominant in Delhi at that time.[89]

Alauddin Khalji's taxation system was probably the one institution from his reign that lasted the longest, surviving indeed into the nineteenth or even the twentieth century. From now on, the land tax (kharaj or mal) became the principal form in which the peasant's surplus was expropriated by the ruling class.

— The Cambridge Economic History of India: c.1200-c.1750, [90]

Alauddin also eliminated the intermediary Hindu rural chiefs, and started collecting the kharaj directly from the cultivators.[91] He did not levy any additional taxes on agriculture, and abolished the cut that the intermediaries received for collecting revenue.[92] Alauddin's demand for tax proportional to land area meant that the rich and powerful villages with more land had to pay more taxes.[93] He forced the rural chiefs to pay same taxes as the others, and banned them from imposing illegal taxes on the peasants.[93] To prevent any rebellions, his administration deprived the rural chiefs of their wealth, horses and arms.[94] By suppressing these chiefs, Alauddin projected himself as the protector of the weaker section of the rural society.[95] However, while the cultivators were free from the demands of the landowners, the high taxes imposed by the state meant a culviator had "barely enough for carrying on his cultivation and his food requirements."[92]

To enforce these land and agrarian reforms, Alauddin set up a strong and efficient revenue administration system. His government recruited many accountants, collectors and agents. These officials were well-paid but were subject to severe punishment if found to be taking bribes. Account books were audited and even small discrepancies were punished. The effect was both large landowners and small-scale cultivators were fearful of missing out on paying their assessed taxes.[96]

Alauddin's government imposed the jizya tax on its non-Muslim subjects, and his Muslim subjects were obligated to contribute zakat.[97] He also levied taxes on residences (ghari) and grazing (chara'i), which were not sanctioned by the Islamic law.[98] In addition, Alauddin demanded four-fifths share of the spoils of war from his soldiers, instead of the traditional one-fifth share (khums).[97]

Market reforms

Alauddin implemented price control measures for a wide variety of market goods.[85] Alauddin's courtier Amir Khusrau and the 14th century writer Hamid Qalandar suggest that Alauddin introduced these changes for public welfare.[99] However, Barani states that Alauddin wanted to reduce the prices so that low salaries were acceptable to his soldiers, and thus, to maintain a large army.[100][101] In addition, Barani suggests that the Hindu traders indulged in profiteering, and Alauddin's market reforms resulted from the Sultan's desire to punish the Hindus.[93]

To ensure that the goods were sold at regulated prices, Alauddin appointed market supervisors and spies, and received independent reports from them. To prevent a black market, his administration prohibited peasants and traders from storing the grains, and established government-run granaries, where government's share of the grain was stored. The government also forced the transport workers to re-settle in villages at specific distances along the Yamuna river to enable rapid transport of grain to Delhi.[102]

Chroniclers such as Khusrau and Barani state that the prices were not allowed to increase during Alauddin's lifetime, even when the rainfall was scarce.[103] The shopkeepers who violated the price control regulations or tried to circumvent them (such as, by using false weights) were given severe punishments.[104]

Military reforms

Alauddin maintained a large standing army, which included 475,000 horsemen according to the 16th-century chronicler Firishta.[105] He managed to raise such a large army by paying relatively low salaries to his soldiers, and introduced market price controls to ensure that the low salaries were acceptable to his soldiers.[101] Although he was opposed to granting lands to his generals and soldiers, he generously rewarded them after successful campaigns, especially those in Deccan.[106]

Alauddin's government maintained a descriptive roll of every soldier, and occasionally conducted strict reviews of the army to examine the horses and arms of the soldiers. To ensure that no horse could be presented twice or replaced by a poor-quality horse during the review, Alauddin established a system of branding the horses.[107]

Social reforms

Although Islam bans alcoholic drinks, drinking was common among the Muslim royals and nobles of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century, and Alauddin himself was a heavy drinker. As part of his measures to prevent rebellions, Alauddin imposed prohibition, because he believed that the rampant use of alcoholic drinks enabled people to assemble, lose their senses and think of rebellion. According to Isami, Alauddin banned alcohol, after a noble condemned him for merrymaking when his subjects were suffering from a famine. However, this account appears to be hearsay.[108]

Subsequently, Alauddin also banned other intoxicants, including cannabis.[108] He also banned gambling, and excommunicated drunkards and gamblers from Delhi, along with vendors of intoxicants.[109] Alauddin's administration strictly punished the violators, and ensured non-availability of alcohol not only in Delhi, but also in its surrounding areas. Nevertheless, alcohol continued to be illegally produced in and smuggled into Delhi.[110] Sometime later, Alauddin relented, and allowed distillation and drinking in private. However, public distribution and drinking of wine remained prohibited.[111]

Alauddin also increased his level of control over the nobility. To prevent rebellions by the nobles, he confiscated their wealth and removed them from their bases of power. Even charitable lands administered by nobles were confiscated. Severe punishments were given for disloyalty. Even wives and children of soldiers rebelling for greater war spoils were imprisoned. An efficient spy network was set up that reached into the private households of nobles. Marriage alliances made between noble families had to be approved by the king.[112]

Alauddin banned prostitution, and ordered all existing prostitutes of Delhi to be married.[109] Firishta states that he classified prostitutes into three grades, and fixed their fees accordingly. However, historian Kishori Saran Lal dismisses this account as inaccurate. Alauddin also took steps to curb adultery by ordering the male adulterer to be castrated and the female adulterer to be stoned to death.[113]

Alauddin banned charlatans, and ordered sorcerers (called "blood-sucking magicians" by his courtier Amir Khusrau) to be stoned to death.[114]

Last days

During the last years of his life, Alauddin suffered from an illness, and became very distrustful of his officers. He started concentrating all the power in the hands of his family and his slaves.[115] He became infatuated with his slave-general Malik Kafur, who became the de facto ruler of the Sultanate after being promoted to the rank of viceroy (Na'ib).[116][117]

Alauddin removed several experienced administrators, abolished the office of wazir (prime minister), and even executed the minister Sharaf Qa'ini. It appears that Malik Kafur, who considered these officers as his rivals and a threat, convinced Alauddin to carry out this purge.[115] Kafur had Alauddin's eldest sons Khizr Khan and Shadi Khan blinded. He also convinced Alauddin to order the killing of his brother-in-law Alp Khan, an influential noble who could rival Malik Kafur's power. The victims allegedly hatched a conspiracy to overthrow Alauddin, but this might be Kafur's propaganda.[115]

Alauddin died on the night of 4 January 1316.[118] Barani claims that according to "some people", Kafur murdered him.[119] Towards the end of the night, Kafur brought the body of Alauddin from the Siri Place and had it buried in Alauddin's mausoleum (which had already been built before Alauddin's death). The mausoleum is said to have been located outside a Jama Mosque, but neither of these structures can be identified with certainty. According to historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena, the ruined foundations of these two structures probably lie under one of the mounds at Siri.[118]

The next day, Kafur appointed Alauddin's young son Shihabuddin as a puppet monarch.[118] However, Kafur was killed shortly after, and Alauddin's elder son Mubarak Khan seized the power.[120]

Alauddin's tomb and the madrasa dedicated to him exist at the back of Qutb complex, Mehrauli, in Delhi.[121]

Personal life

Alauddin's wives included Jalaluddin's daughter, who held the title Malika-i-Jahan, and Alp Khan's sister Mahru.[6] He also married Jhatyapali, the daughter of Hindu king Ramachandra of Devagiri, probably after the 1296 Devagiri raid,[122] or after his 1308 conquest of Devagiri.[123] Alauddin had a son with Jhatyapali, Shihabuddin Omar, who succeeded him as the next Khalji ruler.[122]

Alauddin also married Kamala Devi, a Hindu woman, who was originally the chief queen of Karna, the Vaghela king of Gujarat.[124] She was captured by Khalji forces during an invasion, escorted to Delhi as part of the war booty, and taken into Alauddin's harem.[125][126] She eventually became reconciled to her new life.[127] According to the chronicler Firishta, sometime between 1306-7, Kamala Devi requested Alauddin to secure her daughter Deval Devi from the custody of her father, Raja Karan.[127][128] Alauddin sent an order to Raja Karan telling him to send Deval Devi immediately.[128] Deval Devi was eventually brought to Delhi and lived in the royal palace with her mother.[129]

Malik Kafur, an attractive eunuch slave captured during the Gujarat campaign,[130] caught the fancy of Alauddin.[131] He rose rapidly in Alauddin's service, mainly because of his proven ability as military commander and wise counsellor,[116] and eventually became the viceroy (Na'ib) of the Sultanate.[132] A deep emotional bond developed between Alauddin and Kafur.[131] According to Barani, during the last four or five years of his life, Alauddin fell "deeply and madly in love" with Kafur, and handed over the administration to him.[119] Based on Barani's description, scholars Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai believe that Alauddin and Kafur were in a homosexual relationship.[133] Historian Judith E. Walsh, scholar Nilanjan Sarkar and scholar Thomas Gugler also believe Alauddin and Kafur were lovers in a sexually intimate relationship.[134][135][136] Given his relationship with Kafur, historians believe Alauddin may have been bisexual or even homosexual.[137] Historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena believes that the closeness between the two was not sexual.[138]

Architecture

In 1296, Alauddin constructed the Hauz-i-Alai (later Hauz-i-Khas) water reservoir, which covered an area of 70 acres, and had a stone-masonry wall. Gradually, it became filled with mud, and was desilted by Firuz Shah Tughlaq around 1354. The autobiographical memoirs of Timur, who invaded Delhi in 1398, mention that the reservoir was a source of water for the city throughout the year.[139]

In the early years of the 14th century, Alauddin built the Siri Fort. The fort walls were mainly constructed using rubble (in mud), although there are some traces of ashlar masonry (in lime and lime plaster).[139] Alauddin camped in Siri during the 1303 Mongol invasion, and after the Mongols left, he built the Qasr-i-Hazar Situn palace at the site of his camp. The fortified city of Siri existed in the time of Timur, whose memoirs state that it had seven gates. It was destroyed by Sher Shah Suri in 1545, and only some of its ruined walls now survive.[140]

-

The Hauz-i-Khas

-

Ruined wall of Siri

-

Courts to the east of Quwwat ul-Islam mosque, in Qutb complex added by Khalji in 1300 CE.

-

Alauddin's Madrasa, Qutb complex, Mehrauli, which also has his tomb to the south.

-

The unfinished Alai Minar

Alauddin commissioned the Alai Darwaza, which was completed in 1311, and serves as the southern gateway leading to the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque built by Qutb al-Din Aibak.[141] He also started the construction of the Alai Minar, which was intended to be double to size of the Qutb Minar, but the project was abandoned, probably when he died.[142]

The construction of the Lal Mahal (Red Palace) sandstone building near Chausath Khamba has also been attributed to Alauddin, because its architecture and design is similar to that of the Alai Darwaza.[143]

In 1311, Alauddin repaired the 100-acre Hauz-i-Shamasi reservoir that had been constructed by Shamsuddin Iltutmish in 1229, and also built a dome at its centre.[139]

Religion & relationships with other communities

Views on religion

Like his predecessors, Alauddin was a Sunni Muslim. His administration persecuted the Ismaili (Shia) minorities, after the orthodox Sunnis falsely accused them of permitting incest in their "secret assemblies". Alauddin ordered an inquiry against them sometime before 1311. The inquiry was conducted by the orthodox ulama, who found several Ismailis guilty. Alauddin ordered the convicts to be sawn into two.[144]

Ziauddin Barani, writing half-a-century after his death, mentions that Alauddin did not patronize the Muslim ulama, and that "his faith in Islam was firm like the faith of the illiterate and the ignorant". He further states that Alauddin once thought of establishing a new religion. Just like the Islamic prophet Muhammad's four Rashidun caliphs helped spread Islam, Alauddin believed that he too had four Khans (Ulugh, Nusrat, Zafar and Alp), with whose help he could establish a new religion.[145] Barani's uncle Alaul Mulk convinced him to drop this idea, stating that a new religion could only be found based on a revelation from god, not based on human wisdom.[146] Alaul Mulk also argued that even great conquerors like Genghis Khan had not been able to subvert Islam, and people would revolt against Alauddin for founding a new religion.[147] Barani's claim that Alauddin thought of founding a religion has been repeated by several later chroniclers as well as later historians. Historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena doubts the authenticity of this claim, arguing that it is not supported by Alauddin's contemporary writers.[145]

According to Barani, Alauddin was the first sultan to separate religion from the state. Barani wrote that he:[148]

came to the conclusion that polity and government are one thing, and the rules and decrees of law are another. Royal commands belong to the king, legal decrees rest upon the judgment of the qazis and muftis. In accordance with this opinion, whatever affair of state came before him, he only looked to the public good, without considering whether his mode of dealing with it was lawful or unlawful. He never asked for legal opinions about political matters, and very few learned men visited him.

— Tarikh i Firoze Shahi by Ziauddin Barani[148]

Relationship with Hindus

At times, he exploited Muslim fanaticism against Hindu chiefs and the treatment of the zimmis.[148] Persian historian Wassaf states that he sent an expedition against Gujarat as a holy war and it was not motivated by "lust of conquest".[149] The masnavi Deval Devi—Khizr Khan by Amir Khusrau states that Gujarat was only annexed in the second invasion which took place seven years after the first one, implying the first was merely a plundering raid.[150] At Khambhat, it is said that the citizens were caught by surprise.[151] Wassaf states that "The Muhammadan forces began to kill and slaughter on the right and on the left unmercifully, throughout the impure land, for the sake of Islam, and blood flowed in torrents."[152]

Alauddin and his generals destroyed several Hindu temples during their military campaigns. These temples included the ones at Bhilsa (1292), Devagiri (1295), Vijapur (1298–1310), Somnath (1299), Jhain (1301), Chidambaram (1311) and Madurai (1311).[153]

He compromised with the Hindu chiefs who were willing to accept his suzerainty. In a 1305 document, Khusrau mentions that Alauddin treated the obedient Hindu zamindars (feudal landlords) kindly, and granted more favours to them than they had expected. In his poetic style, Khusrau states that by this time, all the insolent Hindus in the realm of Hind had died on the battlefield, and the other Hindus had bowed their heads before Alauddin. Describing a court held on 19 October 1312, Khusrau writes the ground had become saffron-coloured from the tilaks of the Hindu chiefs bowing before Alauddin.[154] This policy of compromise with Hindus was greatly criticized by a small but vocal set of Muslim extremists, as apparent from Barani's writings.[155]

Alauddin rarely listened to the advice of the orthodox ulama. When he had asked about the position of Hindus under an Islamic state, the qazi Mughis replied that the Hindu "should pay the taxes with meekness and humility coupled with the utmost respect and free from all reluctance. Should the collector choose to spit in his mouth, he should open the same without hesitation, so that the official may spit into it... The purport of this extreme meekness and humility on his part... is to show the extreme submissiveness incumbent upon this race. God Almighty Himself (in the Quran) commands their complete degradation in as much as these Hindus are the deadliest foes of the true prophet. Mustafa has given orders regarding the slaying, plundering and imprisoning of them, ordaining that they must either follow the true faith, or else be slain or imprisoned, and have all their wealth and property confiscated."[156]

Alauddin believed "that the Hindu will never be submissive and obedient to the Musalman unless he is reduced to abject poverty." He undertook measures to impoverish them and felt it was justified because he knew that the chiefs and muqaddams led a luxurious life but never paid a jital in taxes. His vigorous and extensive conquests led to him being viewed as persecutor both at home and abroad, including by Maulana Shamsuddin Turk, Abdul Malik Isami and Wassaf.[157] Barani, while summing up his achievements, mentions that the submission and obedience of the Hindus during the last decade of his reign had become an established fact. He states that such a submission on the part of the Hindus "has neither been seen before nor will be witnessed hereafter".[158]

Under the Mamluk dynasty, obtaining a membership in the higher bureaucracy was difficult for the Indian Muslims and impossible for Hindus. This however seems to have changed under the Khaljis. Khusrau states in Khazainul Futuh that Alauddin had dispatched a 30,000 strong army under a Hindu officer Malik Naik, the Akhur-bek Maisarah, to repel the Mongols.[159] During Ikat Khan's rebellion, the Sultan's life was saved by Hindu soldiers (paiks). Because of the large presence of non-Muslims in the imperial army, Alaul Mulk advised him not to leave Delhi to repel the Mongol Qutlugh Khwaja who had surrounded it.[160]

Relationships with Jains

Per Jain sources, Alauddin held discussions with Jain sages and once specially summoned Acharya Mahasena to Delhi.[161] There was no learned Digambracarya in North India during this period and Mahasena was persuaded by Jains to defend the faith. Alauddin was impressed by his profound learning and asceticism. A Digambara Jain Purancandra was very close to him and the Sultan also maintained contacts with the Shwetambara sages. The Jain poet Acharya Ramachandra Suri was also honored by him.[162]

Kharataragaccha Pattavali, completed in 1336–1337, details atrocities on Jains under his reign including destruction of a religious fair in 1313 while capturing Jabalipura (Jalor). The conditions seem to have changed a year later. Banarasidas in Ardhakathanaka mentions that Jain Shrimala merchants spread over North India and in 1314, the sons of a Shrimala and others along with their cousins with a huge congregation of pilgrims were able to visit a temple at Phaludi despite Ajmer and its neighbourhood under siege by Muslim forces.[162]

Alp Khan who was transferred to Gujarat in 1310, is praised by Jain sources for permitting reconstruction of their temples.[163] Kakkasuri in Nabhi-nandana-jinoddhara-prabandha mentions Alp Khan issuing a farman permitting the Jain merchant Samara Shah to renovate a damaged Shatrunjaya temple.[164] He[who?] is also mentioned to have made huge donations towards repairing Jain temples.[165][166]

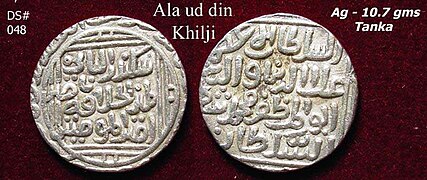

Coins

-

Copper half Gani

-

Copper half Gani

-

Billion Gani

-

Silver Tanka

-

Bilingual coin

-

Silver Tanka Dar al-Islam Mint

-

Silver Tanka Qila Deogir Mint

Khalji minted coins using the title of Sikander Sani. Sikander is Old Persian for 'Alexander', a title popularized by Alexander. While sani is Arabic for to 'Second'. The coin legend (Sikander-e -Sani) translates to 'The Second Alexander' in recognition of his military success.

He had amassed wealth in his treasury through campaigns in Deccan and South India and issued many coins. His coins omitted the mention of the Khalifa, replacing it with the self-laudatory title Sikander-us-sani Yamin-ul-Khilafat.[167] He ceased adding Al-Musta'sim's name, instead adding Yamin-ul-Khilafat Nāsir Amīri 'l-Mu'minīn (The right hand of the Caliphate, the helper of the Commander of the Faithful).[168]

In popular culture

- Alauddin Khalji is the antagonist of Padmavat, an epic poem written by Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi in 1540.[169]

- Khalji was portrayed by M. N. Nambiar in Chitrapu Narayana Rao's film Chittoor Rani Padmini (1963).[170]

- Om Puri portrayed Alauddin Khalji in Doordarshan's historical drama Bharat Ek Khoj.[171]

- Khalji was portrayed by Mukesh Rishi in Sony Entertainment Television's historical drama Chittod Ki Rani Padmini Ka Johur.[172]

- Ranveer Singh portrayed a fictional version of Alauddin in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's epic period drama film Padmaavat.[173]

References

- ^ Lafont, Jean-Marie & Rehana (2010). The French & Delhi : Agra, Aligarh, and Sardhana (1st ed.). New Delhi: India Research Press. p. 8. ISBN 9788183860918.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 321.

- ^ a b c Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 42.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 43.

- ^ A. B. M. Habibullah 1992, p. 322.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 45.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 322.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 323.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 324.

- ^ a b c d e Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 327.

- ^ a b c d Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 328.

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 329.

- ^ a b c Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 330.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 331.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 79.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 80.

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 332.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 333.

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 81.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 221.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Mohammad Habib 1981, p. 266.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 88.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 335.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 338.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 342–347.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 343–346.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 350–352.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 366.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 367.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 368.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 369.

- ^ Mohammad Habib 1981, p. 267.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 164-165.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 366-369.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 372.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 373.

- ^ Asoke Kumar Majumdar 1956, p. 191.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b Peter Jackson 2003, p. 198.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 393.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 175.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 189.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 400–402.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 396.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 135.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 186.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 409-410.

- ^ Ashok Kumar Srivastava 1979, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Ashok Kumar Srivastava 1979, p. 52-53.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 201.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 411.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 411–412.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 412.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 413.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 203.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 415-417.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 213.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2002). Essays in Indian history : towards a Marxist perception. London: Anthem Press. p. 81. ISBN 9781843310617.

- ^ Adhikari, Subhrashis (2016). The Journey of Survivors: 70,000-Year History of Indian Sub-Continent. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482873344.

He became the most powerful ruler of the sultanate after conquering Gujarat, Ranthambore, Mewar, and Devagiri.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 241.

- ^ Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004, p. 172.

- ^ Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 76-79.

- ^ a b Satish Chandra 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, p. 429.

- ^ a b Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004, p. 171-173.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 242.

- ^ Irfan Habib 1982, p. 62.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 357–358.

- ^ a b Satish Chandra 2004, p. 78-80.

- ^ a b c Satish Chandra 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 361.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 80.

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 250.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 243.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 374–376.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2014, p. 103.

- ^ a b Abraham Eraly 2015, p. 166.

- ^ Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 379.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 387.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 257.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 260.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 261.

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 262.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 263.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 76-77.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 264.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Peter Jackson 2003, p. 176.

- ^ a b Abraham Eraly 2015, p. 177-8.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, p. 421.

- ^ a b c Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, p. 425.

- ^ a b R. Vanita & S. Kidwai 2000, p. 132.

- ^ Abraham Eraly 2015, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Qutb Complex: Ala al Din Khalji Madrasa, ArchNet

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Satish Chandra 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 84.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 334.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 86.

- ^ a b Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 190.

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 402.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 297.

- ^ S. Digby 1980, p. 419.

- ^ a b Shanti Sadiq Ali 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Abraham Eraly 2015, p. 177-178.

- ^ R. Vanita & S. Kidwai 2000, p. 113, 132.

- ^ Judith E. Walsh (2006). A Brief History of India. Infobase Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 1438108257.

- ^ Nilanjan Sarkar (2013). "Forbidden Privileges and History-Writing in Medieval India". The Medieval History Journal. 16 (1): 33–4, 48, 55.

- ^ Gugler TK (2011). "Politics of Pleasure: Setting South Asia Straight". South Asia Chronicle. 1: 355–392.

- ^ Craig Lockard (2006). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 366. ISBN 0618386114.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 421.

- ^ a b c Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 375.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 376.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 380.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 376–377.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 399.

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 90.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 91.

- ^ a b c J. L. Mehta. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India – Vol. III: Medieval Indian Society And Culture. Sterling Publishers. p. 102. ISBN 9788120704329.

- ^ M.B. Deopujari (1973). "The Deccan Policy of the Sultanate (1296–1351)". Nagpur University Journal: Humanities. 24. Nagpur University: 39.

- ^ M. Yaseen Mazhar Siddiqi. "Chronology of the Delhi Sultanate". Islam and the Modern Age. 27. Islam and the Modern Age Society; Dr. Zakir Husain Institute of Islamic Societies, Jamia Millia Islamia: 184.

- ^ Mary Boyce (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780415239028.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar 1967, p. 625.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton 2001, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 354.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal. "Political conditions of the Hindus under the Khaljis". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 9. Indian History Congress: 234.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal. "Political conditions of the Hindus under the Khaljis". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 9. Indian History Congress: 234–235.

- ^ Kishori Saran Lal. Theory and Practice of Muslim State in India. Aditya Prakashan. p. 128.

- ^ Mohammad Habib, Afsar Umar Salim Khan. The Political Theory of the Delhi Sultanate: Including a Translation of Ziauddin Barani's Fatawa-i Jahandari, Circa, 1358-9 A.D. Kitab Mahal. p. 150.

- ^ Kanhaiya Lall Srivastava (1980). The position of Hindus under the Delhi Sultanate, 1206–1526. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 142.

- ^ Burjor Avari (April 2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of The Delhi Sultanate. Penguin UK. ISBN 9789351186588.

- ^ a b Pushpa Prasad. "The Jain Community in the Delhi Sultanate". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 54. Indian History Congress: 224, 225.

- ^ Iqtidar Alam Khan (25 April 2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780810864016.

- ^ Hawon Ku Kim. Re-formation of Identity: The 19th-century Jain Pilgrimage Site of Shatrunjaya, Gujarat. University of Minnesota. p. 41.

- ^ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 288.

- ^ Hawon Ku Kim. Re-formation of Identity: The 19th-century Jain Pilgrimage Site of Shatrunjaya, Gujarat. University of Minnesota. p. 38.

- ^ Vipul Singh (2009). Interpreting Medieval India: Early medieval, Delhi Sultanate, and regions (circa 750–1550). Macmillan. p. 17. ISBN 9780230637610.

- ^ Thomas Walker Arnold (2010). The Caliphate. Adam Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 9788174350336.

- ^ Sharma, Manimugdha S. (29 January 2017). "Padmavati isn't history, so what's all the fuss about?". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (13 June 2015). "Chitoor Rani Padmini (1963)". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Ghosh, Avijit (27 February 2017). "Actor's actor Om Puri redefined idea of male lead". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Shah, Shravan (21 September 2017). "Did You Know? Deepika Padukone is not the first actress to play Padmavati on-screen?". www.zoomtv.com. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Palat, Lakshana N (21 November 2017). "Padmavati row: Who was Rani Padmavati's husband Maharawal Ratan Singh?". India Today. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

Bibliography

- A. B. M. Habibullah (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Jalaluddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib; Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (eds.). A Comprehensive History of India. Vol. 5: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 31870180.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - A. L. Srivastava (1966). The Sultanate of Delhi, 711–1526 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. OCLC 607636383.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ashok Kumar Srivastava (1979). The Chahamanas of Jalor. Sahitya Sansar Prakashan. OCLC 12737199.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Asoke Kumar Majumdar (1956). Chaulukyas of Gujarat. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. OCLC 4413150.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Alauddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526). Vol. 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 31870180.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Irfan Habib (1982). "Northern India under the Sultanate: Agrarian Economy". In Tapan Raychaudhuri; Irfan Habib (eds.). The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 1, C.1200-c.1750. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. OCLC 685167335.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mohammad Habib (1981). Politics and Society During the Early Medieval Period. People's Publishing House. OCLC 32230117.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - R. C. Majumdar (1967) [1960]. "Social Life: Hindu and Muslim Relations". The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Delhi Sultanate. Vol. VI (Second ed.). Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. OCLC 634843951.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - R. Vanita; S. Kidwai (2000). Same-Sex Love in India: Readings in Indian Literature. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-05480-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richard M. Eaton (2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim states". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3 (September)). Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies: 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - S. Digby (1990). "Kāfūr, Malik". In E. Van Donzel; B. Lewis; Charles Pellat (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). Vol. 4, Iran–Kha: Brill. p. 419. ISBN 90-04-05745-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Satish Chandra (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526) - Part One. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124110645.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shanti Sadiq Ali (1996). The African Dispersal in the Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0485-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Khazáínu-l Futúh (also known as Táríkh-i 'Aláí), a book describing Alauddin's military career by his court poet Amir Khusrau. English translation, as it appears in The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, by Sir H. M. Elliot. Vol III. 1866-177. Page:67-92.