Art Institute of Chicago

One of the two lion statues (Kemeys, bronze 1893) flanking the Institute's main entrances | |

| |

| Established | 1879; in present location since 1893 |

|---|---|

| Location | 111 South Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60603 USA |

| Collection size | 300,000 works |

| Visitors | 1,539,716 annually (2013)[1] |

| Director | Douglas Druick |

| Public transit access | CTA Bus routes: (6 and 28 line) 'L' and Subway stations: Adams-Wabash: Brown Line Green Line Orange Line Pink Line Purple Line Monroe: Red Line Jackson-Dearborn(at Dearborn Street): Blue Line Metra Train: Van Buren Street Station |

| Website | www.artic.edu |

The Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) is an encyclopedic art museum located in Chicago's Grant Park. It features a collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in its permanent collection. Its holdings also include American art, Old Masters, European and American decorative arts, Asian art, Islamic art, Ancient classical and Egyptian art, modern and contemporary art, and architecture and industrial and graphic design. In addition, it houses the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries.

Tracing its history to a free art school and gallery founded in 1866, the museum is located at 111 South Michigan Avenue in the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District. It is associated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is overseen by Director and President Douglas Druick.[2] It is one of the most visited art museums in the world with about 1.5 million visitors annually (2013), and with one million square feet in eight buildings, it is the second-largest art museum in the United States, after the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1][3]

History

In 1866, a group of 35 artists founded the Chicago Academy of Design in a studio on Dearborn Street, with the intent to run a free school with its own art gallery. The organization was modeled after European art academies, such as the Royal Academy, with Academians and Associate Academians. The Academy's charter was granted in March 1867.

Classes started in 1868, meeting every day at a cost of $10 per month. The Academy's success enabled it to build a new home for the school, a five-story stone building on 66 West Adams Street, which opened on November 22, 1870.

When the Great Chicago Fire destroyed the building in 1871 the Academy was thrown into debt. Attempts to continue despite the loss by using rented facilities failed. By 1878 the Academy was $10,000 in debt. Members tried to rescue the ailing institution by making deals with local businessmen, before some finally abandoned it in 1879 to found a new organization, named the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. When the Chicago Academy of Design went bankrupt the same year, the new Chicago Academy of Fine Arts bought its assets at auction.

In 1882, the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts changed its name to the current Art Institute of Chicago and elected as its first president the banker and philanthropist Charles L. Hutchinson, who "is arguably the single most important individual to have shaped the direction and fortunes of the Art Institute of Chicago"[4]: 5 Hutchinson was a director of many prominent Chicago organizations, including the University of Chicago,[5] and would transform the Art Institute into a world-class museum during his presidency, which he held until his death in 1924.[6] Also in 1882, the organization purchased a lot on the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Van Buren Street for $45,000. The existing commercial building on that property was used for the organization's headquarters, and a new addition was constructed behind it to provide gallery space and to house the school's facilities.[4]: 19 By January 1885 the trustees recognized the need to provide additional space for the organization's growing collection, and to this end purchased the vacant lot directly south on Michigan Avenue. The commercial building was demolished,[7] and the noted architect John Wellborn Root was hired by Hutchinson to design a building that would create an "impressive presence" on Michigan Avenue,[4]: 22–23 and these facilities opened to great fanfare in 1887.[4]: 24

With the announcement of the World's Columbian Exposition to be held in 1892–93, the Art Institute pressed for a building on the lakefront to be constructed for the fair, but to be used by the Institute afterwards. The city agreed, and the building was completed in time for the second year of the fair. Construction costs were met by selling the Michigan/Van Buren property. On October 31, 1893 the Institute moved into the new building. For the opening reception on December 8, 1893, Theodore Thomas and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed. From the 1900s (decade) to the 1960s the school offered with the Logan Family (members of the board) the Logan Medal of the Arts, an award which became one of the most distinguished awards presented to artists in the US.

Between 1959 and 1970 the Institute was a key site in the battle to gain art & documentary photography a place in galleries, under curator Hugh Edwards and his assistants.

As Director of the museum starting in the early 1980s, James N. Wood conducted a major expansion of its collection and oversaw a major renovation and expansion project for its facilities. As "one of the most respected museum leaders in the country", as described by The New York Times, Wood created major exhibitions of works by Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh that set records for attendance at the museum. He retired from the museum in 2004.[8]

In 2006, the Art Institute began construction of "The Modern Wing", an addition situated on the southwest corner of Columbus and Monroe. The project, designed by Pritzker Prize winning architect Renzo Piano, was completed and officially opened to the public on May 16, 2009. The 264,000-square-foot (24,500 m2) building makes the Art Institute the second-largest art museum in the United States. The building houses the museum's world-renowned collections of 20th- and 21st-century art, specifically modern European painting and sculpture, contemporary art, architecture and design, and photography. In 2014, travel review website and forum, Tripadvisor, reviewed millions of travelers' surveys and named the Art Institute the world's best museum.[9]

In April 2015, it was announced that the museum received perhaps the largest gift of art in its history.[10] Collectors Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson donated a "collection [that] is among the world's greatest groups of postwar Pop art ever assembled."[11] The donation includes works by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, Jeff Koons, Charles Ray, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Roy Lichtenstein and Gerhard Richter. The museum agreed to keep the donated work on display for at least 50 years.

Collection

The collection of the Art Institute of Chicago encompasses more than 5,000 years of human expression from cultures around the world and contains more than 260,000 works of art. The museum holds works of art ranging from early Japanese prints to modern American art. It is principally known for one of the United States' finest collection of paintings produced in Western culture.[12][13]

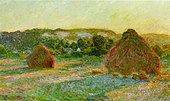

Today, the museum is most famous for its collections of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and American paintings. Highlights included in the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection include more than 30 paintings by Claude Monet including six of his Haystacks and a number of Water Lilies. Also in the collection are important works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir such as Two Sisters (On the Terrace), and Gustave Caillebotte's Paris Street; Rainy Day. Post-Impressionists include Paul Cézanne's The Basket of Apples, and Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair. At the Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is another highlight. The pointillist masterpiece, which also inspired a musical, Georges Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, is prominently displayed. Additionally, Henri Matisse's Bathers by a River, is an important example of his work. Highlights of non-French paintings of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection include Vincent van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles and Self-portrait, 1887.

Among the most important works of the American collection are Mary Cassatt's The Child's Bath, Grant Wood's American Gothic, and Edward Hopper's Nighthawks. The Child's Bath (1892), Cassatt's intimate portrayal, unusual for the time, was first exhibited in 1890s Paris and came into the collection in 1910. Although in the main Cassatt is an impressionist, the work's subject matter and the overhead perspective were inspired by Japanese woodblocks.[14][15] The more formal portrait, American Gothic (1930), by Wood, depicts what has been called "the most famous couple in the world," a dour, rural-American, father and daughter. It was entered into a contest at the Art Institute in 1930, and although not a favorite of some, it won a medal and was acquired by the museum.[16][17] Considered an "icon of American culture",[18][19] Nighthawks (1942) is perhaps Hopper's most famous painting, as well as one of the most recognizable images in American art.[20][21][22] Within months of its completion, Nighthawks was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago for $3,000.[23][18][24] The museum's acquisition of Nighthawks "launched" the painting to its "immense popular recognition." [25]

In addition to paintings, the Art Institute offers a number of other works. Located on the lower level are the Thorne Miniature Rooms which 1:12 scale interiors showcasing American, European and Asian architectural and furniture styles from the Middle Ages to the 1930s (when the rooms were constructed).[26] Another special feature of the museum is the Touch Gallery which is specially designed for the visually impaired. It features several works which museum guests are encouraged to experience though the sense of touch instead of through sight as well as specially designed description plates written in braille.[27] The American Decorative Arts galleries contain furniture pieces designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles and Ray Eames. The Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman galleries hold the mummy and mummy case of Paankhenamun,[28] as well as several gold and silver coins. Whereas, the museum's new Modern Wing (see below) displays additional important works from the 20th and 21st centuries.

Terra Collection

Since April 2005, approximately fifty paintings originally from the Terra Museum (now the Terra Foundation) collection have been on loan to the Department of American Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. The collections of the Terra and the Art Institute are located in a new suite of galleries, and together provide one of the nation’s most comprehensive presentations of American art. The foundation’s collection of American works on paper are housed in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute.

African American Art Collection

Institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago have assisted in creating a place for African American art to be explored freely without the restraints that once accompanied it. The pieces included in the Art Institute of Chicago's African American art collection provide a historical illustration of the progress made by African Americans as well as their continuing struggle.

Specific pieces in this section of the museum give insight into the racial boundaries that existed in the past. Samuel J. Miller's Frederick Douglass daguerreotype is an example of the way some African Americans managed to break away from stereotypes. The daguerreotype had been used by people like Louis Agassiz to show a "type" for ethnic groups. The style of J.T. Zealy's daguerreotype photographs made the subject seem vulnerable, even animalistic. For example, "Delia" (1850) shows a female slave completely exposed and in a sense victimized by the camera. Conversely, the Douglass daguerreotype shows a well-dressed man with a strong expression. This is the complete opposite from the submissiveness of the slaves in the Zealy photos. Douglass represented a new kind of Negro. He was educated and well-respected. This marks a shift in the idea of blackness and the way it is represented.

An artist that took it upon himself to continue to change the way blacks were in portrayed in art is Archibald John Motley, Jr. He aimed to paint "his people" just as they were. Motley said he “wanted to instill a sense of racial pride into his work.[29] Motley attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and had to deal with occasional harassment from white classmates. Yet, he continued to believe that art was the best way to approach racial tensions.[29]: 27

In his piece The Octoroon Girl (1925), Motley challenges the conventional image of an African American. While the woman in the painting fits the mold of "whiteness," she actually is 1/8 black. Breaking away from the traditional views of blacks was indicative of the time period. References such as octoroon or mulatto were used to describe how much "black blood" a person possessed. Motley takes this concept from a negative connotation to one that is independent of social status.

Another piece included in the Art Institute of Chicago's African American art collection is "The Boxer" by Richmond Barthé. Barthe is a significant figure among African American artists because his work was widely exhibited and recognized by reputable organizations. His sculptures depicted African Americans but were sought after pieces in the mainstream art world. In 1942, "The Boxer" coincided with a time period where black boxers such as Joe Louis were fighting white opponents and beating them. This signified a big step for African Americans and equality, at least in the ring.

The changing idea of blackness and African American art was also advanced by artists like Jacob Lawrence. Most of his work focused on African American history and utilized techniques like repetition to emphasize his message. In Graduation, 1948, Lawrence addresses the importance of getting a diploma and how the event can affect a family's morale. This piece went along with Langston Hughes' poem by the same title.[29]: 66 The contrast of black and white in the painting can indicate the fact that such an event is significant to both African and white Americans. An emphasis on education has been central to African American advancement. Frederick Douglas was a major supporter of the idea that education was the path to social equality. "Graduation" manages to depict blacks as academically oriented, a positive image of African Americans.

The use of art as political motivators has been a key factor in African American art. The Art Institute's collection also touches on the social implications of African American art. Black artists are a result of the fight their ancestors faced and the current boundaries that are still left to cross.[30] This powerful medium has evoked discussion about racial tensions and brought attentions that would have otherwise gone under the radar. Such approaches coincided with the emergence of political groups such as the NAACP and Africobra, for artists. African American artists utilized their work to address social and political issues of black people.[31] The combination of forces led to a more prevalent public conversation about racial equality. As African American artists banded together for projects such as the Wall of Respect, their concerns came to the forefront. Their paintbrushes had power.

In essence, the Art Institute of Chicago provides an accurate historical narrative of the lives of African Americans. Comparing daguerreotype images to the more recent pieces show a world of difference. Not only has the perception of African Americans changed, but also African American artists have established a separate school of art. The shift from being defined by African influence, to simply learning from the African link, has helped these artists break the mold they were previously forced to fit.

Architecture

The current building at 111 South Michigan Avenue is the third address for the Art Institute. It was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge of Boston[32] for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition as the World's Congress Auxiliary Building with the intent that the Art Institute occupy the space after the fair closed.

The Art Institute's famous western entrance on Michigan Avenue is guarded by two bronze lion statues created by Edward Kemeys. The sculptor gave them unofficial names: the south lion is "stands in an attitude of defiance," and the north lion is "on the prowl." When a Chicago sports team plays in the championships of their respective league (i.e. the Super Bowl or Stanley Cup Finals, not the entire playoffs), the lions are frequently dressed in that team's uniform. Evergreen wreaths are placed around their necks during the Christmas season.

The east entrance of the museum is marked by the stone arch entrance to the old Chicago Stock Exchange. Designed by Louis Sullivan in 1894, the Exchange was torn down in 1972, but salvaged portions of the original trading room were brought to the Art Institute and reconstructed.

The Art Institute building has the unusual property of straddling open-air railroad tracks. Two stories of gallery space connect the east and west buildings while the Metra Electric and South Shore lines operate below. The lower level of gallery space was formerly the windowless Gunsaulus hall, but is now home to the Alsdorf Galleries showcasing Indian, Southeast Asian and Himalayan Art. During renovation, windows facing north toward Millennium Park were added. The gallery space was designed by Renzo Piano in conjunction with his design of the Modern Wing and features the same window screening used there to protect the art from direct sunlight. The upper level formerly held the modern European galleries, but was renovated in 2008 and now features the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist galleries.

Libraries

Located on the ground floor of the museum is the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries. The Libraries' collections cover all periods of art, but is most known for its extensive collection of 18th to 20th century architecture. It serves the museum staff, college and university students, and is also open to the general public. The Friends of the Libraries, a support group for the Libraries, offers events and special tours for its members.

Modern Wing

On May 16, 2009, the Art Institute opened the Modern Wing, the largest expansion in the museum's history.[33] The 264,000-square-foot (24,500 m2) addition, designed by Renzo Piano, makes the Art Institute the second-largest museum in the US.[3] The architect of record in the City of Chicago for this building was Interactive Design. The Modern Wing is home to the museum's collection of early 20th-century European art, including Pablo Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, Henri Matisse's Bathers by a River, and René Magritte’s Time Transfixed. The Lindy and Edwin Bergman Collection of Surrealist art includes the largest public display of Joseph Cornell's works (37 boxes and collages).[34] The Wing also houses contemporary art from after 1960; new photography, video media, architecture and design galleries including original renderings by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Bruce Goff; temporary exhibition space; shops and classrooms; a cafe and a restaurant, Terzo Piano, that overlooks Millennium Park from its terrace.[35] In addition, the Nichols Bridgeway connects a sculpture garden on the roof of the new wing with the adjacent Millennium Park to the north and a courtyard designed by Gustafson Guthrie Nichol. In 2009, the Modern Wing won a Chicago Innovation Awards.[36]

Selections from the permanent collection

Note that other notable works are in the collection but the following examples are ones in the public domain and for which pictures are available.

Paintings

-

El Greco, Saint Martin and the Beggar, c. 1597–1600

-

Rembrandt, Old Man with a Gold Chain, c. 1631

-

Antoine Watteau, Fête champêtre (Pastoral Gathering), 1718–1721

-

Eugène Delacroix, The Combat of the Giaour and Hassan, 1826

-

John Simpson, The Captive Slave, 1827

-

Édouard Manet, Seascape Calm Weather, 1864–1865

-

Édouard Manet, Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers, 1864–1865

-

Édouard Manet, The Philosopher, (Beggar with Oysters), 1864–1867

-

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1876–1877

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, By the Water, 1880

-

Jules Breton, Song of the Lark, 1884

-

Paul Cézanne, The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque, 1885

-

Edgar Degas, The Millinery Shop, 1885

-

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887

-

Vincent van Gogh, Bedroom in Arles, 1888

-

Claude Monet, Wheatstacks (End of Summer), 1890–1891

-

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples, c.1890s

-

Paul Gauguin, Why are you angry? (No te aha oe Riri), 1896

-

Winslow Homer, After the Hurricane, 1899

-

Odilon Redon, Sita, 1903

-

Pablo Picasso, The Old Guitarist, 1903

-

Pablo Picasso, 1904, Woman with a Helmet of Hair, gouache on tan wood pulp board, 42.7 × 31.3 cm

-

Edgar Degas, Woman at Her Toilette, c. 1900–1905

-

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1906

-

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Head of a Woman (Tête de femme), oil on canvas, 60.3 × 51.1 cm

-

Jean Metzinger, 1913, La Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), oil on canvas, 92.8 × 65.2 cm

-

Wassily Kandinsky, 1912, Landscape With Two Poplars, 78.8 × 100.4 cm

-

Kazimir Malevich, Painterly Realism of a Football Player—Color Masses in the 4th Dimension, 1915

-

Grant Wood, American Gothic 1930

More highlights from the collection

-

Illuminated Manuscript page from a Book of Hours, c. 1440/45

-

One of the Thorne Miniature Rooms, c. 1930s

-

Pieces from the porcelain collection in the Art Institute of Chicago

-

Museum hall

Governance

Attendance

During 2009, attendance was around 2 million—up 33 percent from 2008—in addition to a total of approximately 100,000 museum memberships. Despite a 25 percent boost in museum admission fees, the Modern Wing was a major catalyst for a rise in visitor traffic.[37]

Finances

As of 2011, the Art Institute continues to rebuild its $783 million endowment since the recession.[38] In June 2008, its endowment was $827 million. As of 2012, the museum is rated A1 by Moody’s, its fifth-highest grade, in part reflecting the museum’s pension and retirement liabilities; Standard & Poor’s rates the museum A+, fifth-best. In October 2012, the Art Institute sold about $100 million of taxable and tax-exempt bonds partly to shore up unfunded pension obligations.[39]

The $294 million extension in 2009 was the culmination of a $385 million fundraising campaign—roughly $300 million for design and construction and $85 million for the endowment. Around $370 million were raised primarily from private patrons in Chicago.[40] In 2011, the Art Institute received a $10 million gift from the Jaharis Family Foundation to renovate and expand galleries devoted to Greek, Roman and Byzantine art, as well as to support acquisitions and special exhibitions of that art.[41]

Acquisitions and deaccessioning

In 1990, the Art Institute of Chicago sold 11 works at auction, including paintings by Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Maurice Utrillo and Edgar Degas, to raise the $12 million purchase price of a bronze sculpture, Golden Bird, by Constantin Brâncuși. At the time, the sculpture was owned by the Arts Club of Chicago, which was selling it to buy a new gallery for its other works.[42] In 2005, the museum sold two paintings by Marc Chagall and Auguste Renoir at Sotheby's.[43] In 2011, it auctioned two Picassos (Sur l'impériale traversant la Seine (1901) and Verre et pipe (1919)), Henri Matisse's Femme au fauteuil (1919), and Georges Braque's Nature morte à la guitare (rideaux rouge) (1938) at Christie's in London.[44][45]

Directors

- William M.R. French (1885–1914)

- Newton Carpenter (1914–1916)

- George Eggers (1918–1921)

- Robert Harshe (1921–1938)

- Daniel Catton Rich (1938–1958)

- Allen McNab (1956–1965)

- Charles Cunningham (1965–1972)

- E. Laurence Chalmers (1972–1986)

- James N. Wood (1980–2004)

- James Cuno (2004–2011)

- Douglas Druick (2011–)

Controversy

In 2002, the Art Institute of Chicago filed suit alleging fraud by a small Dallas firm called Integral Investment Management, along with related parties. The museum, which put $43 million of its endowment into funds run by the defendants, claimed that it faced losses of up to 90% on the investments after they soured.[46]

In 2010, the year after the opening of its massive Modern Wing, the Art Institute of Chicago sued the engineering firm Ove Arup for $10 million over what it said were flaws in the concrete floors and air-circulation systems. The suit was settled out of court.[47][48]

The Art Institute in film

Film director John Hughes included a sequence featuring his favorite items in the Art Institute, in his acclaimed 1986 film Ferris Bueller's Day Off, which is set in Chicago. Hughes had first visited the Institute, as a "refuge", while in high school. The sequence features three high school seniors, his main protagonists, admiring the works with a musical sound track.[49] Hughes' commentary on the sequence was used as a reference point by journalist Hadley Freeman in a discussion of the Republican Presidential primary candidates in 2011.[50]

See also

- Forest Idyll

- List of museums and cultural institutions in Chicago

- American Academy of Art

- School of the Art Institute of Chicago

- Visual arts of Chicago

- Alme Meyvis

- Old Man with a Gold Chain

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Visitor Figures 2013: Museum and exhibition attendance numbers compiled and analysed, The Art Newspaper, International Edition, April 2014.

- ^ Viera, Lauren (24 August 2011). "Douglas Druick named director of Art Institute of Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ a b Roberta Smith (13 May 2009). "A Grand and Intimate Modern Art Trove". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b c d Hilliard, Celia (2010). "The Prime Mover" - Charles L. Hutchinson and the making of the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 978-086559-238-4.

- ^ "Few Changes Made - University of Chicago Trustees Hold an Election - Two Vacancies Filled - Other Members Whose Terms Expired Re-Elected - Examinations for Positions as Teachers in the Public Schools of the City". The Daily Inter-Ocean: 1. June 28, 1893.

- ^ Dillon, Diane (2004-09-18). "The Encyclopedia of Chicago - Art Institute of Chicago". The Newberry Library. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ "The Art Institute – The Western Art Movement and its Splendid Achievements in Chicago – The New Home of the Fine Arts – The Ward Collection – The Century, Harper's - The Formal Opening of the New Museum – The Loan Collection – A Noble Triumph". The (Chicago) Inter Ocean. XVI (239): 9. November 20, 1887.

- ^ Kennedy, Randy. "James N. Wood, President of the Getty Trust, Dies at 69", The New York Times, June 14, 2010. Accessed June 21, 2010.

- ^ Grossman, Samantha (2014-09-18). "These Are the 25 Best Museums in the World". Time. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Chicago Tribune (22 April 2015). "Art Institute of Chicago gets its largest gift ever, including 9 Warhols". chicagotribune.com.

- ^ "Gift Worth $400 Million To Art Institute Of Chicago Includes Works By Warhol". NPR.org. 22 April 2015.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian, ed. (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art: The Art Institute of Chicago. Oxford University Press. pp. 813–814. ISBN 978-0192800220.

Celebrated masterpieces: Nighthawks; American Gothic; A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

- ^ "World's most beautiful museums". Fox News.com. 2013-05-03. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

Must-see masterpieces: Georges Seurat's A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte, Nighthawks, and Vincent Van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles.

- ^ Painting profile from the Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ Art Access at the Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ Fineman, Mia, The Most Famous Farm Couple in the World: Why American Gothic still fascinates., Slate, 8 June 2005

- ^ "About This Artwork: American Gothic". The Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Nighthawks". artic.edu.

- ^ "Edward Hopper". A Closer Look. National Gallery of Art. 2006. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ "About This Artwork: Nighthawks, 1942". Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ^ "Edward Hopper's Nighthawks". Present at the Creation. National Public Radio. 2002-10-07. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ^ Wood, James N. (1996). The Art Institute of Chicago, 20th-Century: Painting and Sculpture. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 0865590966.

- ^ The sale was recorded by Josephine Hopper as follows, in volume II, p. 95 of her and Edward's journal of his art: "May 13, '42: Chicago Art Institute - 3,000 + return of Compartment C in exchange as part payment. 1,000 - 1/3 = 2,000." See Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper: A Journal of His Work New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997, p. 63.

- ^ "Art Institute of Chicago". visual-arts-cork.com.

- ^ Levin, Gail (1996). "Edward Hopper's Nighthawks, Surrealism, and the War". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 22 (2): 180–195 at 189, 193–194. doi:10.2307/4104321.

- ^ "Thorne Miniature Rooms". artic.edu. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Touch Gallery". artic.edu. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "Coffin and Mummy Case of Paankhenamun" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ a b c Rossen, Susan F., ed. Selections from The Art Institute of Chicago: African Americans in Art. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1999.

- ^ Parker, Daniel Texidor. African Art: The Diaspora and Beyond. Chicago: Daniel Texidor Parker, 2004. pg. 61.

- ^ The Art of Culture: Evolution of Visual Arts by African American Artists, the Last Fifty Years. Chicago: Africa International House USA, 2003. pg. 18.

- ^ "1879–1913: The Formative Years". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nicolai Ourossof (13 May 2009). "Renzo Piano Embraces Chicago". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Joseph Cornell's Works At The Art Institute". Chicago Tribune. March 23, 1997.

- ^ "A New Kind of Institutional Dining". Zagat.com. May 27, 2009.

- ^ "2009 Chicago Innovation Award winners". Chicago Innovation Awards.

- ^ Lauren Viera (May 9, 2011), Art Institute leader resigns Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Kelly Crow (August 24, 2011), "Chicago's Art Institute Names New Director". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Brian Chappatta (October 9, 2012), Chicago Art Institute Borrows $100 Million for Pensions Businessweek.

- ^ Jason Edward Kaufman (May 13, 2009), Art Institute of Chicago’s massive extension opens The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Kate Taylor (February 27, 2011), A Gift for Art Institute New York Times.

- ^ Chicago Gallery to Sell 11 Works to Buy Brancusi Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1990.

- ^ Carol Vogel (October 26, 2005), Museums Set to Sell Art, and Some Experts Cringe The New York Times.

- ^ Lauren Viera (January 11, 2011), Art Institute paintings to fetch $10-$16 million at auction Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (January 26, 2011). "The Permanent Collection May Not Be So Permanent". The New York Times.

- ^ "Stick to paintings". The Economist. 3 January 2002. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- ^ Finkel, Jori (3 June 2014). "Eli Broad's Art Showcase, Still Unfinished, Sues Over Delays in Los Angeles". The New York Times.

- ^ Kapos, Shia (17 September 2013). "Art Institute closes Modern Wing's 3rd floor for 7 months". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- ^ John Hughes commentary - The Museum scene from Ferris Bueller's Day Off. YouTube. 7 August 2009.

- ^ Two new films reveal the death and triumph of the American dream, Hadley Freeman, The Guardian, November 15, 2011

External links

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Museums in Chicago, Illinois

- Art museums and galleries in Chicago, Illinois

- Art museums in Illinois

- Central Chicago

- Museums of American art

- Asian art museums in the United States

- Institutions accredited by the American Alliance of Museums

- 1879 establishments in Illinois

- Art museums established in 1879

- Visitor attractions along U.S. Route 66

- Visitor attractions in Chicago, Illinois