Bombing of Tokyo

| Bombing of Tokyo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Air raids on Japan, as part of the Pacific War | |||||||

Tokyo burns under B-29 firebomb assault, 26 May 1945 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

325 bombers (279 bombers over target) |

Approximately 638 antiaircraft guns 90 fighter aircraft Professional and 8,000 civilian firefighters | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 43 aircraft destroyed |

80,000 to 130,000 killed (most common estimates) Over one million homeless 267,171 buildings destroyed | ||||||

The Bombing of Tokyo (東京大空襲, Tōkyōdaikūshū) was a series of firebombing air raids by the United States Army Air Forces during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Operation Meetinghouse, which was conducted on the night of 9–10 March 1945, is regarded as the single most destructive bombing raid in human history.[1] 16 square miles (41 km2; 10,000 acres) of central Tokyo were destroyed, leaving an estimated 100,000 civilians dead and over one million homeless.

The US first mounted a seaborne, small-scale air raid on Tokyo in April 1942. Strategic bombing and urban area bombing began in 1944 after the long-range B-29 Superfortress bomber entered service, first deployed from China and thereafter the Mariana Islands. B-29 raids from those islands began on 17 November 1944, and lasted until 15 August 1945, the day of Japanese surrender.[2]

Over 50% of Tokyo's industry was spread out among residential and commercial neighborhoods; firebombing cut the whole city's output in half.[3] Some post-war analysts have called the raid a war crime due to the targeting of civilian infrastructure and the ensuing mass loss of civilian life.[4][5]

Doolittle Raid

The first raid on Tokyo was the Doolittle Raid of 18 April 1942, when sixteen B-25 Mitchells were launched from USS Hornet to attack targets including Yokohama and Tokyo and then fly on to airfields in China. The raid was retaliation against the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid did little damage to Japan's war capability but was a significant propaganda victory for the United States.[6] Launched at longer range than planned when the task force encountered a Japanese picket boat, all of the attacking aircraft either crashed or ditched short of the airfields designated for landing. One aircraft landed in the neutral Soviet Union where the crew was interned, but then smuggled over the border into Iran on 11 May 1943. Two crews were captured by the Japanese in occupied China. Three crewmen from these groups were later executed.[7][8]

B-29 raids

The key development for the bombing of Japan was the B-29 Superfortress strategic bomber, which had an operational range of 3,250 nautical miles (3,740 mi; 6,020 km) and was capable of attacking at high altitude above 30,000 feet (9,100 m), where enemy defenses were very weak. Almost 90% of the bombs dropped on the home islands of Japan were delivered by this type of bomber. Once Allied ground forces had captured islands sufficiently close to Japan, airfields were built on those islands (particularly Saipan and Tinian) and B-29s could reach Japan for bombing missions.[9]

The initial raids were carried out by the Twentieth Air Force operating out of mainland China in Operation Matterhorn under XX Bomber Command, but these could not reach Tokyo. Operations from the Northern Mariana Islands commenced in November 1944 after the XXI Bomber Command was activated there.[10]

The high-altitude bombing attacks using general-purpose bombs were observed to be ineffective by USAAF leaders due to high winds—later discovered to be the jet stream—which carried the bombs off target.[11]

Between May and September 1943, bombing trials were conducted on the Japanese Village set-piece target, located at the Dugway Proving Grounds. These trials demonstrated the effectiveness of incendiary bombs against wood-and-paper buildings, and resulted in Curtis LeMay ordering the bombers to change tactics to utilize these munitions against Japan.[12]

The first such raid was against Kobe on 4 February 1945. Tokyo was hit by incendiaries on 25 February 1945 when 174 B-29s flew a high altitude raid during daylight hours and destroyed around 643 acres (260 ha) (2.6 km2) of the snow-covered city, using 453.7 tons of mostly incendiaries with some fragmentation bombs.[13] After this raid, LeMay ordered the B-29 bombers to attack again but at a relatively low altitude of 5,000 to 9,000 ft (1,500 to 2,700 m) and at night, because Japan's anti-aircraft artillery defenses were weakest in this altitude range, and the fighter defenses were ineffective at night. LeMay ordered all defensive guns but the tail gun removed from the B-29s so that the aircraft would be lighter and use less fuel.[14]

Operation Meetinghouse

On the night of 9–10 March 1945,[15] 334 B-29s took off to raid with 279 of them dropping 1,665 tons of bombs on Tokyo. The bombs were mostly the 500-pound (230 kg) E-46 cluster bomb which released 38 napalm-carrying M-69 incendiary bomblets at an altitude of 2,000–2,500 ft (610–760 m). The M-69s punched through thin roofing material or landed on the ground; in either case they ignited 3–5 seconds later, throwing out a jet of flaming napalm globs. A lesser number of M-47 incendiaries were also dropped: the M-47 was a 100-pound (45 kg) jelled-gasoline and white phosphorus bomb which ignited upon impact. In the first two hours of the raid, 226 of the attacking aircraft unloaded their bombs to overwhelm the city's fire defenses.[16] The first B-29s to arrive dropped bombs in a large X pattern centered in Tokyo's densely populated working class district near the docks in both Koto and Chūō city wards on the water; later aircraft simply aimed near this flaming X. The individual fires caused by the bombs joined to create a general conflagration, which would have been classified as a firestorm but for prevailing winds gusting at 17 to 28 mph (27 to 45 km/h).[17] Approximately 15.8 square miles (4,090 ha) of the city were destroyed and some 100,000 people are estimated to have died.[18][19] A grand total of 282 of the 339 B-29s launched for "Meetinghouse" made it to the target, 27 of which were lost due to being shot down by Japanese air defenses, mechanical failure, or being caught in updrafts caused by the fires.[20]

Results

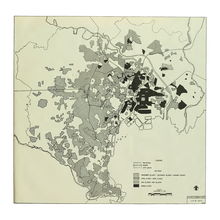

Damage to Tokyo's heavy industry was slight until firebombing destroyed much of the light industry that was used as an integral source for small machine parts and time-intensive processes. Firebombing also killed or made homeless many workers who had taken part in the war industry. Over 50% of Tokyo's industry was spread out among residential and commercial neighborhoods; firebombing cut the whole city's output in half.[3] The destruction and damage was especially severe in the eastern areas of the city.[citation needed]

Emperor Hirohito's tour of the destroyed areas of Tokyo in March 1945 was the beginning of his personal involvement in the peace process, culminating in Japan's surrender six months later.[21]

Casualty estimates

The US Strategic Bombing Survey later estimated that nearly 88,000 people died in this one raid, 41,000 were injured, and over a million residents lost their homes. The Tokyo Fire Department estimated a higher toll: 97,000 killed and 125,000 wounded. The Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department established a figure of 83,793 dead and 40,918 wounded and 286,358 buildings and homes destroyed.[22] Historian Richard Rhodes put deaths at over 100,000, injuries at a million and homeless residents at a million.[23] These casualty and damage figures could be low; Mark Selden wrote in Japan Focus:

The figure of roughly 100,000 deaths, provided by Japanese and American authorities, both of whom may have had reasons of their own for minimizing the death toll, seems to be arguably low in light of population density, wind conditions, and survivors' accounts. With an average of 103,000 inhabitants per square mile (396 people per hectare) and peak levels as high as 135,000 per square mile (521 people per hectare), the highest density of any industrial city in the world, and with firefighting measures ludicrously inadequate to the task, 15.8 square miles (41 km2) of Tokyo were destroyed on a night when fierce winds whipped the flames and walls of fire blocked tens of thousands fleeing for their lives. An estimated 1.5 million people lived in the burned out areas.[22]

In his 1968 book, reprinted in 1990, historian Gabriel Kolko cited a figure of 125,000 deaths.[24] Elise K. Tipton, professor of Japan studies, arrived at a rough range of 75,000 to 200,000 deaths.[25] Donald L. Miller, citing Knox Burger, stated that there were "at least 100,000" Japanese deaths and "about one million" injured.[26]

The Operation Meetinghouse firebombing of Tokyo on the night of 9 March 1945 was the single deadliest air raid of World War II,[27] greater than Dresden,[28] Hamburg, Hiroshima, or Nagasaki as single events.[29][30]

Postwar recovery

After the war, Tokyo struggled to rebuild. In 1945 and 1946, the city received a share of the national reconstruction budget roughly proportional to its amount of bombing damage (26.6%), but in successive years Tokyo saw its share dwindle. By 1949, Tokyo was given only 10.9% of the budget; at the same time there was runaway inflation devaluing the money. Occupation authorities such as Joseph Dodge stepped in and drastically cut back on Japanese government rebuilding programs, focusing instead on simply improving roads and transportation. Tokyo did not experience fast economic growth until the 1950s.[31]

Memorials

Between 1948 and 1951 the ashes of 105,400 people killed in the attacks on Tokyo were interred in Yokoamicho Park in Sumida Ward. A memorial to the raids was opened in the park in March 2001.[32]

After the war, Japanese author Katsumoto Saotome, a survivor of 10 March 1945 firebombing, helped start a library about the raid in Koto Ward called the Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage. The library contains documents and literature about the raid plus survivor accounts collected by Saotome and the Association to Record the Tokyo Air Raid.[33]

Postwar Japanese politics

In 2007, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe apologized in print, acknowledging Japan's guilt in the bombing of Chinese cities and civilians beginning in 1938. He wrote that the Japanese government should have surrendered as soon as losing the war was inevitable, an action that would have prevented Tokyo from being firebombed in March 1945, as well as subsequent bombings of other cities.[34] In 2013, during his second term as prime minister, Abe's cabinet stated that the raids were "incompatible with humanitarianism, which is one of the foundations of international law", but also noted that it is difficult to argue that the raids were illegal under the international laws of the time.[35][36]

In 2007, 112 members of the Association for the Bereaved Families of the Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids brought a class action against the Japanese government, demanding an apology and 1.232 billion yen in compensation. Their suit charged that the Japanese government invited the raid by failing to end the war earlier, and then failed to help the civilian victims of the raids while providing considerable support to former military personnel and their families.[37] The plaintiffs' case was dismissed at the first judgement in December 2009, and their appeal was rejected.[38] The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court, which rejected their case in May 2013.[39]

Partial list of missions

B-29

- 24 November 1944: 111 B-29s hit an aircraft factory on the rim of the city.[40]

- 27 November 1944: 81 B-29s hit the dock and urban area and 13 targets of opportunity.[41]

- 29–30 November 1944: two incendiary raids on industrial areas, burning 2,773 structures.[41]

- 19 February 1945: 119 B-29s hit port and urban area.

- 24 February 1945: 229 B-29s plus over 1600 carrier-based planes.[42]

- 25 February 1945: 174 B-29s dropping incendiaries destroy 28,000 buildings.[43]

- 4 March 1945: 159 B-29s hit urban area.[44]

- 10 March 1945: 334 B-29s dropping incendiaries destroy 267,000 buildings; 25% of city[44] (Operation Meetinghouse) killing some 100,000.

- 2 April 1945: 100 B-29s bomb the Nakajima aircraft factory.[45]

- 3 April 1945: 68 B-29s bomb the Koizumi aircraft factory and urban areas in Tokyo.[45]

- 7 April 1945: 101 B-29s bomb the Nakajima aircraft factory again[45]

- 13 April 1945: 327 B-29s bomb the arsenal area.[46]

- 20 July 1945: 1 B-29 drops a Pumpkin bomb (bomb with same ballistics as the Fat Man nuclear bomb) through overcast. It aimed at, but missed, the Imperial Palace.[47]

- 8 August 1945: 60 B-29s bomb the aircraft factory and arsenal.

- 10 August 1945: 70 B-29s bomb the arsenal complex.[48]

Other

- 16–17 February 1945: carrier-based aircraft, including dive bombers, escorted by Hellcat fighters attacked Tokyo. Over two days, over 1,500 American planes and hundreds of Japanese planes were in the air. "By the end of 17 February, more than five hundred Japanese planes, both on the ground and in the air, had been lost, and Japan's aircraft works had been badly hit. The Americans lost eighty planes."[49]

- 18 August 1945: The last U.S. air combat casualty of World War II occurred during mission 230 A-8, when two Consolidated B-32 Dominators of the 386th Bomb Squadron, 312th Bomb Group, launched from Yontan Airfield, Okinawa, for a photo reconnaissance run over Tokyo, Japan. Both bombers were attacked by several Japanese fighters of both the 302nd Naval Air Group at Atsugi and the Yokosuka Air Group that made 10 gunnery passes. Japanese IJNAS aces Sadamu Komachi and Saburō Sakai were part of this attack. The B-32 piloted by 1st Lt. John R. Anderson, was hit at 20,000 feet; cannon fire knocked out the number two (port inner) engine, and three crew were injured, including Sgt. Anthony J. Marchione, 19, of the 20th Reconnaissance Squadron, who took a 20 mm hit to the chest and died 30 minutes later. Tail gunner Sgt. John Houston destroyed one attacker. The lead bomber, Consolidated B-32-20-CF Dominator, 42-108532, "Hobo Queen II", piloted by 1st Lt. James Klein, was not seriously damaged but the second Consolidated B-32-35-CF Dominator, 42-108578, lost an engine, had the upper turret knocked out of action, and partially lost rudder control. Both bombers landed at Yontan Airfield just past ~1800 hrs. having survived the last air combat of the Pacific war. The following day, propellers were removed from Japanese aircraft as part of the surrender agreement. Marchione was buried on Okinawa on 19 August, his body being returned to his Pottstown, Pennsylvania home on 18 March 1949. He was interred in St. Aloysius Old Cemetery with full military honors.[50] "Hobo Queen II" was dismantled at Yonton Airfield following a 9 September nosegear collapse and damage during lifting. B-32, 42-108578, was scrapped at Kingman, Arizona after the war.[51]

References

- ^ Long, Tony (9 March 2011). "March 9, 1945: Burning the Heart Out of the Enemy". wired.com. Wired Magazine.

1945: In the single deadliest air raid of World War II, 330 American B-29s rain incendiary bombs on Tokyo, touching off a firestorm that kills upwards of 100,000 people, burns a quarter of the city to the ground, and leaves a million homeless.

- ^ Craven, Wesley Frank, and James Lea Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume Five, the Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953, page 558.

- ^ a b United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report (Pacific War), p. 18.

- ^ Rauch, Jonathan. "Firebombs Over Tokyo: America's 1945 attack on Japan's capital remains undeservedly obscure alongside Hiroshima and Nagasaki". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Carney, Matthew. "Tokyo WWII firebombing, the single most deadly bombing raid in history, remembered 70 years on". ABC Australia. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Shapiro, Isaac (2009). Edokko: Growing Up a Foreigner in Wartime Japan. iUniverse. p. 115. ISBN 1-4401-4124-X.

- ^ The Illustrated History of WWII, by Dr. John Ray, p.126, Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2003)

- ^ http://www.doolittleraider.com

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. New York: Back Bay Books. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-316-02375-7.

- ^ Video: B-29s Rule Jap Skies,1944/12/18 (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Morgan, Robert; Powers, Ron. The Man Who Flew The Memphis Belle. Dutton. p. 279. ISBN 0-525-94610-1.

- ^ Hopkins, William B. (2009). The Pacific War: The Strategy, Politics, and Players That Won the War. Zenith Imprint. p. 322. ISBN 0-7603-3435-8.

- ^ Bradley, F.J. (1999). No Strategic Targets Left. Turner Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 9781563114830.

- ^ Miller, Donald L.; Commager, Henry Steele (2001). The Story of World War II. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 447–449. ISBN 9780743227186.

- ^ Crane, Conrad C. "The War: Firebombing (Germany & Japan)." PBS. Accessed 24 August 2014.

- ^ Bradley 1999, pp. 34–35

- ^ Rodden, Robert M.; John, Floyd I.; Laurino, Richard (May 1965). Exploratory Analysis of Firestorms., Stanford Research Institute, pp. 39, 40, 53–54. Office of Civil Defense, Department of the Army, Washington D.C.

- ^ Freeman Dyson. (1 November 2006), "Part I: A Failure of Intelligence", Technology Review, MIT

- ^ David McNeill. The night hell fell from the sky. Japan Focus, 10 March 2005 Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Morgan, Robert; Powers, Ron. The Man Who Flew The Memphis Belle. Dutton. p. 314. ISBN 0-525-94610-1.

- ^ Bradley, F. J. No Strategic Targets Left. "Contribution of Major Fire Raids Toward Ending WWII" p. 38. Turner Publishing Company, limited edition. ISBN 1-56311-483-6.

- ^ a b Selden, Mark (2 May 2007). "A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq". Japan Focus. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard. "The Making of the Atomic Bomb". p 599. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks (1984) ISBN 0-684-81378-5.

- ^ Kolko, Gabriel (1990) [1968]. The Politics of War: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1943–1945. pp. 539–40.

- ^ Tipton, Elise K. (2002). Modern Japan: A Social and Political History. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 0-585-45322-5.

- ^ Miller 2001, p. 456.

- ^ "9 March 1945: Burning the Heart Out of the Enemy". Wired. Condé Nast Digital. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Technical Sergeant Steven Wilson (25 February 2010). "This month in history: The firebombing of Dresden". Ellsworth Air Force Base. United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Laurence M. Vance (14 August 2009). "Bombings Worse than Nagasaki and Hiroshima". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Joseph Coleman (10 March 2005). "1945 Tokyo Firebombing Left Legacy of Terror, Pain". CommonDreams.org. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Andre Sorensen. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty First Century RoutledgeCurzon, 2004. ISBN 0-415-35422-6.

- ^ Karacas 2000, pp. 521–523

- ^ Aukema Justin, "Author sees parallels between prewar, nuclear indoctrination", Japan Times, 20 March 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Karacas, Cary (2010). "Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids 焼夷弾空襲と忘れられた被災市民―東京大空襲犠牲者による損害賠償請求訴訟". JapanFocus.org. ISSN 1557-4660.

- ^ "Japanese government says 1945 Tokyo bombing was 'against humanitarian principles'". Japan Daily News. Mainichi Shimbun. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "東京大空襲で答弁書 「人道主義に合致せず」". 47NEWS. 共同通信社. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "東京大空襲、国を提訴 遺族ら12億円賠償請求". 47NEWS. Kyodo News. 9 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "東京大空襲の賠償認めず 「救済対象者の選別困難」". 47NEWS. Kyodo News. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "東京大空襲で原告敗訴が確定 最高裁が上告退ける". 47NEWS. Kyodo News. 9 May 2013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Hillenbrand (2010), pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand (2010), p. 263.

- ^ Hillenbrand (2010), p. 274.

- ^ Tactical Mission Report 38. 21st Bomber Command. 1945.

- ^ a b U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology. March 1945. Archived 2 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Historical Studies Office. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ a b c Sloggett, David (18 July 2013). A Century of Air Power: The Changing Face of Warfare 1912–2012. Pen and Sword. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-78159-192-5.

- ^ Dorr, Robert F. (20 December 2012). B-29 Superfortress Units of World War 2. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-835-4.

- ^ Norman Polmar. The Enola Gay: The B-29 That Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, pp. 24. Potomac Books (2004) ISBN 1-57488-836-6.

- ^ "American missions against Tokyo and Tokyo Bay". Pacific Wrecks. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Hillenbrand (2010), pp. 273–274.

- ^ The Last to Die | Military Aviation | Air & Space Magazine. Airspacemag.com. Retrieved on 5 August 2010.

- ^ 1942 USAAF Serial Numbers (42-91974 to 42-110188). Joebaugher.com. Retrieved on 5 August 2010.

Further reading

- Caidin, Martin (1960). A Torch to the Enemy: The Fire Raid on Tokyo. Balantine Books. ISBN 0-553-29926-3. D767.25.T6 C35.

- Coffey, Thomas M. (1987). Iron Eagle: The Turbulent Life of General Curtis LeMay. Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 0-517-55188-8.

- Crane, Conrad C. (1994). The cigar that brought the fire wind: Curtis LeMay and the strategic bombing of Japan. JGSDF-U.S. Army Military History Exchange. ASIN B0006PGEIQ.

- Frank, Richard B. (2001). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100146-1.

- Grayling, A. C. (2007). Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan. New York: Walker Publishing Company Inc. ISBN 0-8027-1565-6.

- Greer, Ron (2005). Fire from the Sky: A Diary Over Japan. Jacksonville, Arkansas, U.S.A.: Greer Publishing. ISBN 0-9768712-0-3.

- Guillian, Robert (1982). I Saw Tokyo Burning: An Eyewitness Narrative from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. Jove Pubns. ISBN 0-86721-223-3.

- Hillenbrand, Laura (2010). Unbroken. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6416-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoyt, Edwin P. (2000). Inferno: The Fire Bombing of Japan, March 9 – August 15, 1945. Madison Books. ISBN 1-56833-149-5.

- Jablonski, Edward (1971). "Air War Against Japan". Airwar Outraged Skies/Wings of Fire. An Illustrated history of Air power in the Second World War. Doubleday. ASIN B000NGPMSQ.

- Karacas, Cary (2010). "Place, Public Memory and the Tokyo Air Raids". The Geographical Review. 100 (4).

- Lemay, Curtis E.; Bill Yenne (1988). Superfortress: The Story of the B-29 and American Air Power. McGraw-Hill Companies. ISBN 0-07-037164-4.

- McGowen, Tom (2001). Air Raid!: The Bombing Campaign. Brookfield, Connecticut, U.S.A.: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 0-7613-1810-0.

- Morgan, Robert; Powers, Ron (2001). The Man Who Flew The Memphis Belle: Memoir of a WWII Bomber Pilot. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94610-1.

- Shannon, Donald H. (1976). United States air strategy and doctrine as employed in the strategic bombing of Japan. U.S. Air University, Air War College. ASIN B0006WCQ86.

- Smith, Jim; Malcolm Mcconnell (2002). The Last Mission: The Secret History of World War II's Final Battle. Broadway. ISBN 0-7679-0778-7.

- Tillman, Barrett (2010). Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan, 1942–1945. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-8440-7.

- Werrell, Kenneth P. (1998). Blankets of Fire. Smithsonian. ISBN 1-56098-871-1.

External links

- 67 Japanese cities firebombed in World War II.

- Army Air Forces in World War II.

- The Center of the Tokyo Raid and War Damages / Introduction.

- Barrell, Tony (1997). "Tokyo's Burning". ABC Online. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 August 1997. Retrieved 3 November 2006. Transcript of a radio documentary/commentary on the Tokyo firebombing with excerpts from interviews with participants and witnesses.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. V: The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944 to August 1945". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- Hansell, Jr., Haywood S. (1986). "The Strategic Air War Against Germany and Japan: A Memoir". Project Warrior Studies. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- World War II aerial operations and battles of the Pacific theatre

- Aerial operations and battles of World War II by town or city

- Japan in World War II

- World War II strategic bombing of Japan

- 1940s conflicts

- History of Tokyo

- Japanese home islands campaign

- Firebombings in Japan

- 1940s in Tokyo

- Japan–United States military relations