Dog anatomy

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Czech. (July 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Dog anatomy comprises the anatomical studies of the visible parts of the body of a canine. Details of structures vary tremendously from breed to breed, more than in any other animal species, wild or domesticated,[1] as dogs are highly variable in height and weight. The smallest known adult dog was a Yorkshire Terrier, that stood only 6.3 cm (2.5 in) at the shoulder, 9.5 cm (3.7 in) in length along the head-and-body, and weighed only 113 grams (4.0 oz). The largest known dog was an English Mastiff which weighed 155.6 kg (343 lb) and was 250 cm (98 in) from the snout to the tail.[2] The tallest dog is a Great Dane that stands 106.7 cm (42.0 in) at the shoulder.[3]

Physical characteristics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

Like most predatory mammals, the dog has powerful muscles, a cardiovascular system that supports both sprinting and endurance, and teeth for catching, holding, and tearing.

The dog's skeleton provides the ability to jump and leap. Their legs can propel them forward rapidly, leaping as necessary to chase and overcome prey. They have small, tight feet, walking on their toes (thus having a digitigrade stance and locomotion); their rear legs are fairly rigid and sturdy; the front legs are loose and flexible, with only muscle attaching them to the torso.

The dog's muzzle size will come with the breed. The sizes of the muzzle have different names. Dogs with medium muzzles, such as the German shepherd dog, are called mesocephalic and dogs with a pushed in muzzle, such as the pug, are called brachacephalic. Today's toy breeds have skeletons that mature in only a few months, while giant breeds such as the Mastiffs take 16 to 18 months for the skeleton to mature. Dwarfism has affected the proportions of some breeds' skeletons, as in the Basset Hound.

All dogs (and all living Canidae) have a ligament connecting the spinous process of their first thoracic (or chest) vertebra to the back of the axis bone (second cervical or neck bone), which supports the weight of the head without active muscle exertion, thus saving energy.[4] This ligament is analogous in function (but different in exact structural detail) to the nuchal ligament found in ungulates.[4] This ligament allows dogs to carry their heads while running long distances, such as while following scent trails with their nose to the ground, without expending much energy.[4]

Dogs have disconnected shoulder bones (lacking the collar bone of the human skeleton) that allow a greater stride length for running and leaping. They walk on four toes, front and back, and have vestigial dewclaws on their front legs and on their rear legs. When a dog has extra dewclaws in addition to the usual one the rear, the dog is said to be "double dewclawed".

Size

Dogs are highly variable in height and weight. The smallest known adult dog was a Yorkshire Terrier, that stood only 6.3 cm (2.5 in) at the shoulder, 9.5 cm (3.7 in) in length along the head-and-body, and weighed only 113 grams (4.0 oz). The largest known dog was an English Mastiff which weighed 155.6 kg (343 lb) and was 250 cm (98 in) from the snout to the tail.[2] The tallest dog is a Great Dane that stands 106.7 cm (42.0 in) at the shoulder.[3]

In 2007, a study identified a gene that is proposed as being responsible for size. The study found a regulatory sequence next to the gene Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and together the gene and regulatory sequence "is a major contributor to body size in all small dogs." Two variants of this gene were found in large dogs, making a more-complex reason for large breed size. The researchers concluded this gene's instructions to make dogs small must be at least 12,000 years old, and it is not found in wolves.[5] Another study has proposed that lap dogs (small dogs) are among the oldest existing dog types.[6]

Skull

In 1986, a study of skull morphology found that the domestic dog is morphologically distinct from all other canids except the wolf-like canids. "The difference in size and proportion between some breeds are as great as those between any wild genera, but all dogs are clearly members of the same species."[7] In 2010, a study of dog skull shape compared to extant carnivorans proposed that "The greatest shape distances between dog breeds clearly surpass the maximum divergence between species in the Carnivora. Moreover, domestic dogs occupy a range of novel shapes outside the domain of wild carnivorans."[8]

The domestic dog compared to the wolf shows the greatest variation in the size and shape of the skull (Evans 1979) that range from 7 to 28 cm in length (McGreevy 2004). Wolves are dolichocephalic (long skulled) but not as extreme as some breeds of such as greyhounds and Russian wolfhounds (McGreevy 2004). Canine brachycephaly (short-skulledness) is found only in domestic dogs and is related to paedomorphosis (Goodwin 1997). Puppies are born with short snouts, with the longer skull of dolichocephalic dogs emerging in later development (Coppinger 1995). Other differences in head shape between brachycephalic and dolichocephalic dogs include changes in the craniofacial angle (angle between the basilar axis and hard palate) (Regodón 1993), morphology of the temporomandibular joint (Dickie 2001), and radiographic anatomy of the cribriform plate (Schwarz 2000).[9]

One study found that the relative reduction in dog skull length compared to its width (the Cephalic Index) was significantly correlated to both the position and the angle of the brain within the skull. This was regardless of the brain size or the body weight of the dog.[10]

Skeleton

- Dog skeletal features

-

Lateral view of a dog skeleton

-

Lateral view of a dog skull - jaws open

-

Lateral view of a dog skull

-

Frontal view of a dog skull

-

Image of dog teeth

Coat

Domestic dogs often display the remnants of counter-shading, a common natural camouflage pattern. The general theory of countershading is that an animal that is lit from above will appear lighter on its upper half and darker on its lower half where it will usually be in its own shade.[11][12] This is a pattern that predators can learn to watch for. A countershaded animal will have dark coloring on its upper surfaces and light coloring below.[11] This reduces the general visibility of the animal. One reminder of this pattern is that many breeds will have the occasional "blaze", stripe, or "star" of white fur on their chest or undersides.[12]

A study found the that the genetic basis that explains coat colors in horse coats and cat coats did not apply to dog coats.[13] The project took samples from 38 different breeds to find the gene (a beta defensin gene) responsible for dog coat color. One version produces yellow dogs, and a mutation produces black. All dog coat colors are modifications of black or yellow.[14] For example, the white in white miniature schnauzers is a cream color, not albinism (a genotype of e/e at MC1R.)

Modern dog breeds exhibit a diverse array of fur coats, including dogs without fur, such as the Mexican Hairless Dog. Dog coats vary in texture, color, and markings, and a specialized vocabulary has evolved to describe each characteristic.[15]

Tail

There are many different shapes for dog tails: straight, straight up, sickle, curled, cork-screw. In some breeds, the tail is traditionally docked to avoid injuries (especially for hunting dogs).[16] It can happen that some puppies are born with a short tail or no tail in some breeds.[17] Dogs have a violet gland or supracaudal gland on the dorsal (upper) surface of their tails.

Foot pad

Dogs can stand, walk and run on snow and ice for long periods of time. When a dog's footpad is exposed to the cold, heat loss is prevented by an adaptation of the blood system that recirculates heat back into the body, drains blood from the skin surface, and retains warm blood in the pad surface.[18]

Dewclaw

There is some debate about whether a dewclaw helps dogs to gain traction when they run because, in some dogs, the dewclaw makes contact when they are running and the nail on the dewclaw often wears down in the same way that the nails on their other toes do, from contact with the ground. However, in many dogs the dewclaws never make contact with the ground; in this case, the dewclaw's nail never wears away, and it is then often trimmed to keep it to a safe length.

The dewclaws are not dead appendages. They can be used to lightly grip bones and other items that dogs hold with the paws. However, in some dogs these claws may not appear to be connected to the leg at all except by a flap of skin; in such dogs the claws do not have a use for gripping as the claw can easily fold or turn.[2]

There is also some debate as to whether dewclaws should be surgically removed.[citation needed]The argument for removal states that dewclaws are a weak digit, barely attached to the leg, so that they can rip partway off or easily catch on something and break, which can be extremely painful and prone to infection. Others say the pain of removing a dewclaw is far greater than any other risk. For this reason, removal of dewclaws is illegal in many countries. There is, perhaps, an exception for hunting dogs, who can sometimes tear the dewclaw while running in overgrown vegetation. [3] If a dewclaw is to be removed, this should be done when the dog is a puppy, sometimes as young as 3 days old, though it can also be performed on older dogs if necessary (though the surgery may be more difficult then). The surgery is fairly straight forward and may even be done with only local anesthetics if the digit is not well connected to the leg. Unfortunately many dogs can't resist licking at their sore paws following the surgery, so owners need to remain vigilant.

In addition, for those dogs whose dewclaws make contact with the ground when they run, it is possible that removing them could be a disadvantage for a dog's speed in running and changing of direction, particularly in performance dog sports such as dog agility.

Genitalia

Senses

Vision

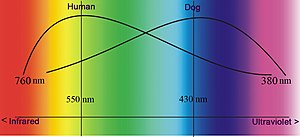

Like most mammals, dogs have only two types of cone photoreceptor, making them dichromats.[19][20][21][22] These cone cells are maximally sensitive between 429 nm and 555 nm. Behavioural studies have shown that the dog's visual world consists of yellows, blues and grays,[22] but they have difficulty differentiating red and green making their color vision equivalent to red–green color blindness in humans (deuteranopia). When a human perceives an object as "red", this object appears as "yellow" to the dog and the human perception of "green" appears as "white", a shade of gray. This white region (the neutral point) occurs around 480 nm, the part of the spectrum which appears blue-green to humans. For dogs, wavelengths longer than the neutral point cannot be distinguished from each other and all appear as yellow.[22]

Dogs use color instead of brightness to differentiate light or dark blue/yellow.[23][24][25][26] They are less sensitive to differences in grey shades than humans and also can detect brightness at about half the accuracy of humans.[27]: page140

The dog's visual system has evolved to aid proficient hunting.[19] While a dog's visual acuity is poor (that of a poodle's has been estimated to translate to a Snellen rating of 20/75[19]), their visual discrimination for moving objects is very high; dogs have been shown to be able to discriminate between humans (e.g., identifying their human guardian) at a range of between 800 and 900 metres (2,600 and 3,000 ft), however this range decreases to 500–600 metres (1,600–2,000 ft) if the object is stationary.[19]

Dogs have a temporal resolution of between 60 and 70 Hz. This means that domestic dogs are unlikely to perceive modern TV screens in the same way as humans because these are optimized for humans at 50–60 Hz.[27]: page140 Dogs can detect a change in movement that exists in a single diopter of space within their eye. Humans, by comparison, require a change of between 10 and 20 diopters to detect movement.[28]

As crepuscular hunters, dogs often rely on their vision in low light situations: They have very large pupils, a high density of rods in the fovea, an increased flicker rate, and a tapetum lucidum.[19] The tapetum is a reflective surface behind the retina that reflects light to give the photoreceptors a second chance to catch the photons. There is also a relationship between body size and overall diameter of the eye. A range of 9.5 and 11.6 mm can be found between various breeds of dogs. This 20% variance can be substantial and is associated as an adaptation toward superior night vision.[27]: page139

The eyes of different breeds of dogs have different shapes, dimensions, and retina configurations.[29] Many long-nosed breeds have a "visual streak"—a wide foveal region that runs across the width of the retina and gives them a very wide field of excellent vision. Some long-muzzled breeds, in particular, the sighthounds, have a field of vision up to 270° (compared to 180° for humans). Short-nosed breeds, on the other hand, have an "area centralis": a central patch with up to three times the density of nerve endings as the visual streak, giving them detailed sight much more like a human's. Some broad-headed breeds with short noses have a field of vision similar to that of humans.[20][21]

Most breeds have good vision, but some show a genetic predisposition for myopia – such as Rottweilers, with which one out of every two has been found to be myopic.[19] Dogs also have a greater divergence of the eye axis than humans, enabling them to rotate their pupils farther in any direction. The divergence of the eye axis of dogs ranges from 12–25° depending on the breed.[28]

Experimentation has proven that dogs can distinguish between complex visual images such as that of a cube or a prism. Dogs also show attraction to static visual images such as the silhouette of a dog on a screen, their own reflections, or videos of dogs; however, their interest declines sharply once they are unable to make social contact with the image.[27]: page142

Hearing

The frequency range of dog hearing is between 16-40 Hz (compared to 20–70 Hz for humans) and up to 45–60 kHz (compared to 13–20 kHz for humans), which means that dogs can detect sounds far beyond the upper limit of the human auditory spectrum.[21][30][31][32]

Dogs have ear mobility that allows them to rapidly pinpoint the exact location of a sound. Eighteen or more muscles can tilt, rotate, raise, or lower a dog's ear. A dog can identify a sound's location much faster than a human can, as well as hear sounds at four times the distance.[33]

Those with more natural ear shapes, like those of wild canids like the fox, generally hear better than those with the floppier ears of many domesticated species.[citation needed]

Smell

While the human brain is dominated by a large visual cortex, the dog brain is dominated by a large olfactory cortex.[19] Dogs have roughly forty times more smell-sensitive receptors than humans, ranging from about 125 million to nearly 300 million in some dog breeds, such as bloodhounds.[19] This is thought to make its sense of smell up to 40 times more sensitive than human's.[34]: 246 These receptors are spread over an area about the size of a pocket handkerchief (compared to 5 million over an area the size of a postage stamp for humans).[35][36] Dogs' sense of smell also includes the use of the Vomeronasal organ, which is used primarily for social interactions.

The dog has mobile nostrils that helps it determine the direction of the scent. Unlike humans, the dog does not need to fill up his lungs as he continuously brings the odor into his nose in bursts of 3-7 sniffs. The dog's nose has a bony structure inside that humans don't have, which allows the air that has been sniffed to pass over a bony shelf and many odor molecules stick to it. The air above this shelf is not washed out when the dog breathes normally, so the scent molecules accumulate in the nasal chambers and the scent builds with intensity, allowing the dog to detect the most faint of odors.[34]: 247

One study into the learning ability of dogs compared to wolves indicated that dogs have a better sense of smell than wolves when locating hidden food, but there has yet been no experimental data to support this view.[37]

The wet nose, or rhinarium, is essential for determining the direction of the air current containing the smell. Cold receptors in the skin are sensitive to the cooling of the skin by evaporation of the moisture by air currents.[38]

Taste

Dogs have around 1,700 taste buds compared to humans with around 9,000. The sweet taste buds in dogs respond to a chemical called furaneol which is found in many fruits and in tomatoes. It appears that dogs do like this flavor and it probably evolved because in a natural environment dogs frequently supplement their diet of small animals with whatever fruits happen to be available. Because of dogs' dislike of bitter tastes, various sprays, and gels have been designed to keep dogs from chewing on furniture or other objects. Dogs also have taste buds that are tuned for water, which is something they share with other carnivores but is not found in humans. This taste sense is found at the tip of the dog's tongue, which the part of the tongue that he curls to lap water. This area responds to water at all times but when the dog has eaten salty or sugary foods the sensitivity to the taste of water increases. It is proposed that this ability to taste water evolved as a way for the body to keep internal fluids in balance after the animal has eaten things that will either result in more urine being passed, or will require more water to adequately process. It certainly appears that when these special water taste buds are active, dogs seem to get an extra pleasure out of drinking water, and will drink copious amounts of it.[39]

Touch

The main difference between human and dog touch is the presence of specialised whiskers known as vibrissae. Vibrissae are present above the dog’s eyes, below their jaw, and on their muzzle. They are sophisticated sensing organs. Vibrissae are more rigid and embedded much more deeply in the skin than other hairs, and have a greater number of receptor cells at their base. They can detect air currents, subtle vibrations, and objects in the dark. They provide an early warning system for objects that might strike the face or eyes, and probably help direct food and objects towards the mouth.[40]

Magnetic sensitivity

Dogs may prefer, when they are off the leash and Earth's magnetic field is calm, to urinate and defecate with their bodies aligned on a north-south axis.[41] Another study suggested that dogs can see the earth's magnetic field.[42][43]

Temperature regulation

Primarily, dogs regulate their body temperature through panting,[44] and sweating via their paws. Panting moves cooling air over the moist surfaces of the tongue and lungs, transferring heat to the atmosphere.

Dogs and other canids also possess a very well-developed set of nasal turbinates, an elaborate set of bones and associated soft-tissue structures (including arteries and veins) in the nasal cavities. These turbinates allow for heat exchange between small arteries and veins on their maxilloturbinate surfaces (the surfaces of turbinates positioned on maxilla bone) in a counter-current heat-exchange system. Dogs are capable of prolonged chases, in contrast to the ambush predation of cats, and these complex turbinates play an important role in enabling this (cats only possess a much smaller and less-developed set of nasal turbinates).[45]: 88 This same complex turbinate structure help conserve water in arid environments. The water conservation and thermoregulatory capabilities of these well-developed turbinates in dogs may have been crucial adaptations that allowed dogs (including both domestic dogs and their wild prehistoric ancestors) to survive in the harsh Arctic environment and other cold areas of northern Eurasia and North America, which are both very dry and very cold.[45]: 87

References

- ^ Scientists fetch useful information from dog genome publications, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, December 7, 2005; published online in Bio-Medicine quote: "Phenotypic variation among dog breeds, whether it be in size, shape, or behavior, is greater than for any other animal"

- ^ a b "World's Largest Dog". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Guinness World Records – Tallest Dog Living". Guinness World Records. 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Wang, Xiaoming and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. pp.97-8

- ^ Sutter NB, Bustamante CD, Chase K, et al. (Apr 2007). "A single IGF1 allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs". Science. 316 (5821): 112–5. doi:10.1126/science.1137045. PMC 2789551. PMID 17412960.

- ^ Ostrander EA (Sep–Oct 2007). "Genetics and the Shape of Dogs; Studying the new sequence of the canine genome shows how tiny genetic changes can create enormous variation within a single species". Am. Sci.

- ^ Wayne, Robert K. (1986). "Cranial Morphology of Domestic and Wild Canids: The Influence of Development on Morphological Change". Evolution. 40 (2): 243. doi:10.2307/2408805. JSTOR 2408805.

- ^ Drake, Abby Grace; Klingenberg, Christian Peter (2010). "Large‐Scale Diversification of Skull Shape in Domestic Dogs: Disparity and Modularity". The American Naturalist. 175 (3): 289. doi:10.1086/650372. PMID 20095825.

- ^ Roberts, Taryn; McGreevy, Paul; Valenzuela, Michael (2010). "Human Induced Rotation and Reorganization of the Brain of Domestic Dogs". PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11946. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011946. PMID 20668685.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) All cited in Roberts. - ^ Roberts, Taryn; McGreevy, Paul; Valenzuela, Michael (2010). "Human Induced Rotation and Reorganization of the Brain of Domestic Dogs". PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11946. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011946. PMID 20668685.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Klappenbach, Laura (2008). "What is Counter Shading?". About.com. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ a b Cunliffe, Juliette (2004). "Coat Types, Colours and Markings". The Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds. Paragon Publishing. pp. 20–3. ISBN 0-7525-6561-3.

- ^ Candille SI, Kaelin CB, Cattanach BM, et al. (Nov 2007). "A -defensin mutation causes black coat color in domestic dogs". Science. 318 (5855): 1418–23. doi:10.1126/science.1147880. PMC 2906624. PMID 17947548.

- ^ Stanford University Medical Center, Greg Barsh et al. (2007, October 31). Genetics Of Coat Color In Dogs May Help Explain Human Stress And Weight. ScienceDaily. Retrieved September 29, 2008

- ^ "Genetics of Coat Color and Type in Dogs". Sheila M. Schmutz, Ph.D., Professor, University of Saskatchewan. October 25, 2008. Retrieved 11/05 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The Case for Tail Docking". cdb.org. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "Bourbonnais pointer or 'short tail pointer'".

- ^ Ninomiya, Hiroyoshi; Akiyama, Emi; Simazaki, Kanae; Oguri, Atsuko; Jitsumoto, Momoko; Fukuyama, Takaaki (2011). "Functional anatomy of the footpad vasculature of dogs: Scanning electron microscopy of vascular corrosion casts". Veterinary Dermatology. 22 (6): 475. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3164.2011.00976.x. PMID 21438930.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Coren, Stanley (2004). How Dogs Think. First Free Press, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2232-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b A&E Television Networks (1998). Big Dogs, Little Dogs: The companion volume to the A&E special presentation. A Lookout Book. GT Publishing. ISBN 1-57719-353-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Alderton, David (1984). The Dog. Chartwell Books. ISBN 0-89009-786-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Jennifer Davis (1998). "Dr. P's Dog Training: Vision in Dogs & People". Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ "Dogs CAN see in colour: Scientists dispel the myth that canines can only see in black and white". Daily Mail. London. 23 July 2013.

- ^ Anna A. Kasparson; Jason Badridze; Vadim V. Maximov (Jul 2013). "Colour cues proved to be more informative for dogs than brightness". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1766): 20131356. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1356.

- ^ Jay Neitz; Timothy Geist; Gerald H. Jacobs (1989). "Color Vision in the Dog" (PDF). Visual neuroscience. 3: 119–125. doi:10.1017/s0952523800004430.

- ^ Jay Neitz; Joseph Carroll; Maureen Neitz (Jan 2001). "Color Vision — Almost Reason Enough for Having Eyes" (PDF). Optics & Photonics News: 26–33.

- ^ a b c d Miklósi, Adám (2009). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199295852.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-929585-2.

- ^ a b Mech, David. Wolves, Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. The University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 98.

- ^ "Catalyst: Dogs' Eyes". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Elert, Glenn; Timothy Condon (2003). "Frequency Range of Dog Hearing". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "How well do dogs and other animals hear". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "How well do dogs and other animals hear".

- ^ "Dog Sense of Hearing". seefido.com. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ a b Coren, Stanley "How To Speak Dog: Mastering the Art of Dog-Human Communication" 2000 Simon & Schuster, New York.

- ^ "Understanding a Dog's Sense of Smell". Dummies.com. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "The Dog's Sense of" (PDF). Alabama and Auburn Universities. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ Virányi, Z. F.; Range, F. (2013). "Social learning from humans or conspecifics: Differences and similarities between wolves and dogs". Frontiers in Psychology. 4. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00868.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dijkgraaf S.;Vergelijkende dierfysiologie;Bohn, Scheltema en Holkema, 1978, ISBN 90-313-0322-4

- ^ Coren, Stanley

- ^ Santos, A "Puppy and Dog Care: An Essential Puppy Training Guide", 2015 Amazon Digital Services, Inc. [1]

- ^ Hart, V.; Nováková, P.; Malkemper, E.; Begall, S.; Hanzal, V. R.; Ježek, M.; Kušta, T. Š.; Němcová, V.; Adámková, J.; Benediktová, K. I.; Červený, J.; Burda, H. (2013). "Dogs are sensitive to small variations of the Earth's magnetic field". Frontiers in Zoology. 10: 80. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-10-80.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nießner, Christine; Denzau, Susanne; Malkemper, Erich Pascal; Gross, Julia Christina; Burda, Hynek; Winklhofer, Michael; Peichl, Leo (2016). "Cryptochrome 1 in Retinal Cone Photoreceptors Suggests a Novel Functional Role in Mammals". Scientific Reports. 6: 21848. doi:10.1038/srep21848. PMC 4761878. PMID 26898837.

- ^ Magnetoreception molecule found in the eyes of dogs and primates MPI Brain Research, 22 February 2016

- ^ http://www.petplace.com/dogs/how-do-dogs-sweat/page1.aspx

- ^ a b Wang, Xiaoming (2008) Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231509435