Dracula (1931 English-language film)

| Dracula | |

|---|---|

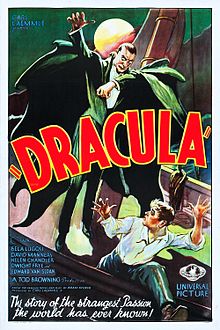

1931 one sheet movie poster (Style F) | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by | Garrett Fort |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Freund |

| Edited by |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 85 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $355,000[2] |

Dracula is a 1931 American Pre-Code vampire-horror film directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula. The film was produced by Universal and is based on the 1924 stage play Dracula by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston, which in turn is loosely based on the novel Dracula by Bram Stoker.[3]

Plot

Renfield (Dwight Frye) is a solicitor traveling to Count Dracula's (Bela Lugosi) castle in Transylvania on a business matter. The people in the local village fear that vampires inhabit the castle and warn Renfield not to go there. Renfield refuses to stay at the inn and asks his carriage driver to take him to the Borgo Pass. Renfield is driven to the castle by Dracula's coach, with Dracula disguised as the driver. En route, Renfield sticks his head out the window to ask the driver to slow down, but sees the driver has disappeared; a bat leads the horses.

Renfield enters the castle welcomed by the charming but eccentric Count, who unbeknownst to Renfield, is a vampire. They discuss Dracula's intention to lease Carfax Abbey in London, where he intends to travel the next day. Dracula hypnotizes Renfield into opening a window. Renfield faints as a bat appears and Dracula's three wives close in on him. Dracula waves them away, then attacks Renfield himself.

Aboard the schooner Vesta, Renfield is a raving lunatic slave to Dracula, who hides in a coffin and feeds on the ship's crew. When the ship reaches England, Renfield is discovered to be the only living person. Renfield is sent to Dr. Seward's sanatorium adjoining Carfax Abbey.

At a London theatre, Dracula meets Seward (Herbert Bunston). Seward introduces his daughter Mina (Helen Chandler), her fiancé John Harker (David Manners) and the family friend Lucy Weston (Frances Dade). Lucy is fascinated by Count Dracula. That night, Dracula enters her room and feasts on her blood while she sleeps. Lucy dies the next day after a string of transfusions.

Renfield is obsessed with eating flies and spiders. Professor Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) analyzes Renfield's blood and discovers his obsession. He starts talking about vampires, and that afternoon Renfield begs Seward to send him away, claiming his nightly cries may disturb Mina's dreams. When Dracula calls Renfield with wolf howling, Renfield is disturbed by Van Helsing showing him wolfsbane, which Van Helsing says is used for protection from vampires.

Dracula visits Mina, asleep in her bedroom, and bites her. The next evening, Dracula enters for a visit and Van Helsing and Harker notice that he does not have a reflection. When Van Helsing reveals this to Dracula, he smashes the mirror and leaves. Van Helsing deduces that Dracula is the vampire behind the recent tragedies.

Mina leaves her room and runs to Dracula in the garden, where he attacks her. She is found by the maid. Newspapers report that a woman in white is luring children from the park and biting them. Mina recognizes the lady as Lucy, risen as a vampire. Harker wants to take Mina to London for safety, but is convinced to leave Mina with Van Helsing. Van Helsing orders Nurse Briggs (Joan Standing) to take care of Mina when she sleeps, and not to remove the wreath of wolfsbane from her neck.

Renfield escapes from his cell and listens to the men discuss vampires. Before his attendant takes Renfield back to his cell, Renfield relates to them how Dracula convinced Renfield to allow him to enter the sanitorium by promising him thousands of rats with blood and life in them. Dracula enters the Seward parlour and talks with Van Helsing. Dracula states that Mina now belongs to him, and warns Van Helsing to return to his home country. Van Helsing swears to excavate Carfax Abbey and destroy Dracula. Dracula attempts to hypnotize Van Helsing, but the latter's resolve proves stronger. As Dracula lunges at Van Helsing, he withdraws a crucifix from his coat, forcing Dracula to retreat.

Harker visits Mina on a terrace, and she speaks of how much she loves "nights and fogs". A bat flies above them and squeaks to Mina. She then attacks Harker but Van Helsing and Seward save him. Mina confesses what Dracula has done to her, and tells Harker their love is finished.

Dracula hypnotizes Briggs into removing the wolfsbane from Mina's neck and opening the windows. Van Helsing and Harker see Renfield heading for Carfax Abbey. They see Dracula with Mina in the abbey. When Harker shouts to Mina, Dracula thinks Renfield has led them there and kills him. Dracula is hunted by Van Helsing and Harker knowing that Dracula is forced to sleep in his coffin during daylight, and the sun is rising. Van Helsing prepares a wooden stake while Harker searches for Mina. Van Helsing impales Dracula, killing him, and Mina returns to normal.

Cast

- Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula

- Helen Chandler as Mina Seward

- David Manners as John Harker

- Dwight Frye as Renfield

- Edward Van Sloan as Van Helsing

- Herbert Bunston as Dr Seward

- Frances Dade as Lucy Weston

- Joan Standing as Nurse Briggs (in an error on the opening credits, she is misidentified as "Maid")[4]

- Charles K. Gerrard as Martin, Renfield's attendant

Background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

Bram Stoker's novel had already been filmed without permission as Nosferatu in 1922 by German expressionist film maker F. W. Murnau. Bram Stoker's widow sued for plagiarism and copyright infringement, and the courts decided in her favor, essentially ordering that all prints of Nosferatu be destroyed.[4] Enthusiastic young Hollywood producer Carl Laemmle, Jr. also saw the box office potential in Stoker's gothic chiller, and he legally acquired the novel's film rights. Initially, he wanted Dracula to be a spectacle on a scale with the lavish silent films The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925).[citation needed]

Already a huge hit on Broadway, the Deane/Balderston Dracula play would become the blueprint as the production gained momentum. The screenwriters carefully studied the silent, unauthorized version, Nosferatu for inspiration. One bit of business lifted directly from a nearly identical scene in Nosferatu that does not appear in Stoker's novel was the early scene at the Count's castle when Renfield accidentally pricks his finger on a paper clip and it starts to bleed, and Dracula creeps toward him with glee, only to be repelled when the crucifix falls in front of the bleeding finger.

Production

Decision on casting the title role proved problematic. Initially, Laemmle was not at all interested in Lugosi, in spite of good reviews for his stage portrayal. Laemmle instead considered other actors, including Paul Muni, Chester Morris, Ian Keith, John Wray, Joseph Schildkraut, Arthur Edmund Carewe and William Courtenay. Lugosi had played the role on Broadway, and to his good fortune, happened to be in Los Angeles with a touring company of the play when the film was being cast.[4] Against the tide of studio opinion, Lugosi lobbied hard and ultimately won the executives over, thanks in part to him accepting a paltry $500 per week salary for seven weeks of work, amounting to $3,500.[4][5]

According to numerous accounts, the production is alleged to have been a mostly disorganized affair,[6] with the usually meticulous Tod Browning leaving cinematographer Karl Freund to take over during much of the shoot, making Freund something of an uncredited director on the film.

The peasants at the beginning are praying in Hungarian, and the signs of the village are also in Hungarian. This was because when Bram Stoker wrote the original novel, the Borgo Pass was near Transylvania and Hungary. Now that area is part of Romania.[7]

The scenes of crew members on the ship struggling in the violent storm were lifted from a Universal silent film, The Storm Breaker (1925). Photographed at silent film projection speed, this accounts for the jerky, sped-up appearance of the footage when projected at 24 frames per second sound film speed and cobbled together with new footage of Dracula and Renfield.[4] Jack Foley was the foley artist who produced the sound effects.[8]

Cinematic process

The film's histrionic dramatics from the stage play are also reflected in its special effects, which are limited to fog, lighting, and large flexible bats. Dracula's transition from bat to person is always done off-camera. The film also employs extended periods of silence and character close-ups for dramatic effect, and employs several intertitles and a closeup of a newspaper article to advance the story, holdovers from silent films. One point made by online film critic James Berardinelli[9] is that the actors' performance style seems to belong to the silent era. Director Tod Browning had a solid reputation as a silent film director, having made them since 1915, but he never felt completely at ease with sound films.[4] He only directed a few more, the last in 1939.

Soundtrack

Due to the limitations of adding a musical score to a film's soundtrack during 1930 and 1931, no score had ever been composed specifically for the film. The music heard during the opening credits, an excerpt from Act II of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake, was re-used in 1932 for another Universal horror film, The Mummy. During the theatre scene where Dracula meets Dr. Seward, Harker, Mina and Lucy, the end of the overture to Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg can also be heard as well as the dark opening of Schubert's "Unfinished Symphony" in B minor.

1998 score

In 1998 composer Philip Glass was commissioned to compose a musical score for the classic film. The score was performed by the Kronos Quartet under direction of Michael Reisman, Glass's usual conductor.

Of the project, Glass said:

- The film is considered a classic. I felt the score needed to evoke the feeling of the world of the 19th century — for that reason I decided a string quartet would be the most evocative and effective. I wanted to stay away from the obvious effects associated with horror films. With [the Kronos Quartet] we were able to add depth to the emotional layers of the film.

The film, with this new score, was released by Universal Studios in 1999 in the VHS format. Universal's DVD releases allow the viewer to choose between the unscored soundtrack or the Glass score. The soundtrack, Dracula, was released by Nonesuch Records in 1999.[10] Glass and the Kronos Quartet performed live during showings of the film in 1999 and 2000.[11][12][13]

Release

When the film finally premiered at the Roxy Theatre in New York on February 12, 1931 (released two days later throughout the United States),[5] newspapers reported that members of the audiences fainted in shock at the horror on screen. This publicity, shrewdly orchestrated by the film studio, helped ensure people came to see the film, if for no other reason than curiosity. Dracula was a big gamble for a major Hollywood studio to undertake. In spite of the literary credentials of the source material, it was uncertain if an American audience was prepared for a serious full length supernatural chiller. Though America had been exposed to other chillers before, such as The Cat and the Canary (1927), this was a horror story with no comic relief or trick ending that downplayed the supernatural. Nervous executives breathed a collective sigh of relief when Dracula proved to be a huge box office sensation. Within 48 hours of its opening at New York's Roxy Theatre, it had sold 50,000 tickets,[5] building a momentum that culminated in a $700,000 profit, the largest of Universal's 1931 releases.[14]

Reception

The film was generally well received by critics. Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times called it "the best of the many mystery films", characterizing Browning's direction as "imaginative" and Helen Chandler's performance as "excellent".[15] Variety praised the film for its "remarkably effective background of creepy atmosphere" and wrote, "It is difficult to think of anybody who could quite match the performance in the vampire part of Bela Lugosi, even to the faint flavor of foreign speech that fits so neatly."[16] Film Daily declared the film "a fine melodrama" and also lauded Lugosi's performance, calling it "splendid" and remarking that he had created "one of the most unique and powerful roles of the screen".[17] Time called it "an exciting melodrama, not as good as it ought to be but a cut above the ordinary trapdoor-and-winding-sheet type of mystery film."[18] John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote a negative review, remarking that "there is no real illusion in the picture" and "This whole vampire business falls pretty flat".[19] The Chicago Tribune did not think the film was as scary as the stage version, calling its framework "too obvious" and "its attempts to frighten too evident", but still concluded that it was "quite a satisfactory thriller."[20]

Later in 1931, Universal would release Frankenstein to even greater acclaim. Universal in particular would become the forefront of early horror cinema, with a canon of films including The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and The Wolf Man (1941).

Censorship

The film was originally released with a running time of 85 minutes;[1] when it was reissued in 1936, the Production Code was being strictly enforced. For that reissue, at least two scenes are known to have been censored.[4]

- The most significant deletion was an epilogue which played only during the film's initial run. In a scene similar to the prologue from Frankenstein, and also featuring Universal stalwart Edward Van Sloan, he reappeared in a "curtain speech" and informed the audience: "Just a moment, ladies and gentlemen! A word before you go. We hope the memories of Dracula and Renfield won't give you bad dreams, so just a word of reassurance. When you get home tonight and the lights have been turned out and you are afraid to look behind the curtains — and you dread to see a face appear at the window — why, just pull yourself together and remember that after all, there are such things as vampires!"[4][21] This epilogue was removed out of fear of offending religious groups by encouraging a belief in the supernatural. This scene is still missing and presumed lost.[4]

- Audio of Dracula's off-camera "death groans" at the end of the film were shortened by partial muting, as were Renfield's screams as he is killed; these pieces of soundtrack were later restored by MCA-Universal for its laser disc and subsequent DVD releases (with the exception of the 2004 multi-film "Legacy Collection" edition[22]).

Legacy

Today, Dracula is widely regarded as a classic of the era and of its genre. In 2000, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". It was ranked 79th on Bravo's countdown of The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[23]

To many film lovers and critics alike, Lugosi's portrayal is widely regarded as the definitive Dracula. Lugosi had a powerful presence and authority on-screen. The slow, deliberate pacing of his performance ("I bid you… welcome!" and "I never drink… wine!") gave his Dracula the air of a walking, talking corpse, which terrified 1931 movie audiences. He was just as compelling with no dialogue, and the many close-ups of Lugosi's face in icy silence jumped off the screen. With this mesmerizing performance, Dracula became Bela Lugosi's signature role, his Dracula a cultural icon, and he himself a legend in the classic Universal Horror film series.

However, Dracula would ultimately become a role which would prove to be both a blessing and a curse. Despite his earlier stage successes in a variety of roles, from the moment Lugosi donned the cape on screen, it would forever see him typecast as the Count.[24]

Browning would go on to direct Lugosi once more in another vampire thriller, Mark of the Vampire, a 1935 remake of his lost silent film London After Midnight (1927).

Also, the film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #85[25]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Count Dracula – #33 Villain[26]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Count Dracula: "Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make." – #83[27]

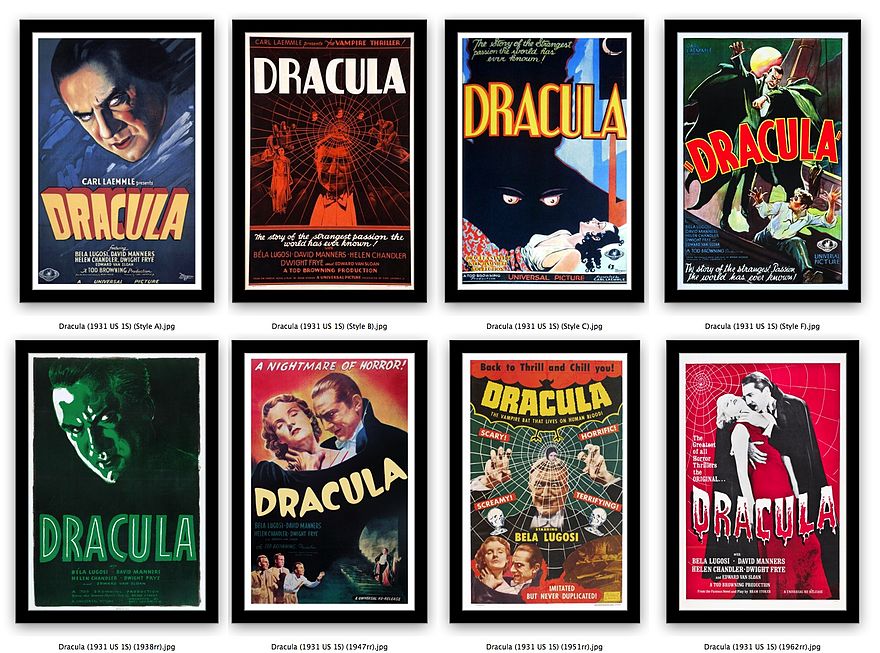

Original posters from the 1931 release (see below picture, top row) are very rare and extremely valuable, typically auctioning for more than $100,000. In 2009, an original one sheet then owned by actor Nicolas Cage sold for $310,700.[28] Re-release posters (see below picture, bottom row) are also valuable.

Iconography

This film, and the 1920s stage play by Deane & Balderston, contributed much of Dracula's popular iconography, much of which vastly differs from Stoker's novel. In the novel and in the German silent film Nosferatu (1922), Dracula's appearance is repulsive; Lugosi portrays the Count as a handsome, charming nobleman. The Deane-Balderston play and this film also introduced the now iconic images of Dracula entering his victims' bedrooms through French doors/windows, wrapping his satin-lined cape around victims, and more emphasis on Dracula transforming into a bat. In the Stoker novel, he variously transformed into a bat or a wolf,[4] a mist or "elemental dust."

The now classic Dracula line, "I never drink ... wine", is original to this film. It did not appear in Stoker's novel or the original production of the play. When the play was revived on Broadway in 1977 starring Frank Langella, the line was added to the script.[4]

Sequels

In 1936, five years after release, Universal released Dracula's Daughter, a direct sequel that starts immediately after the end of the first film. A second sequel, Son of Dracula starring Lon Chaney, Jr., followed in 1943. The Count returned to life in three more Universal films of the mid-1940s: 1944's House of Frankenstein, 1945's House of Dracula and 1948's comedy Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Universal would only cast Lugosi as Dracula in one more film, the aforesaid Abbott and Costello vehicle,[29] giving the role to John Carradine for the mid-1940s "monster rally" films, although Carradine admittedly more closely resembled Stoker's physical description from the book. Many of the familiar images of Dracula are from stills of the older Lugosi made during the filming of the 1948 comedy, so there remain two confusingly distinct incarnations of Lugosi as Dracula, seventeen years apart in age. As Lugosi played a vampire in three other movies during his career,[30] this contributed to the public misconception that he portrayed Dracula on film many times.

Alternate versions

In the early days of sound films, it was common for Hollywood studios to produce "Foreign Language Versions" of their films using the same sets, costumes and so on. While Browning filmed during the day, at night George Melford was using the sets to make the Spanish-language version Dracula, starring Carlos Villarías as Conde Drácula. Long thought lost, a print of this Dracula was discovered in the 1970s and restored.[31][32] This was included as a bonus feature on the "Classic Monster Collection" DVD in 1999, the "Legacy Collection" DVD in 2004, the "75th Anniversary Edition DVD" set in 2006, and on "Universal Monsters: The Essential Collection" on Blu-ray in 2012.

A third, silent, version of the film was also released. In 1931, some theaters had not yet been wired for sound and during this transition period, many studios released alternate silent versions with intertitles.[4]

See also

- Bela Lugosi filmography

- Dracula in popular culture

- Dracula (1979), based on the same Deane/Balderston play

- Gothic film – Notable films

- Universal Monsters

Further reading

- Tod Browning's Dracula by Gary D. Rhodes (2015) Tomahawk Press, ISBN 0956683452

References

- ^ a b "Dracula". The Film Daily (Volume 55) Jan-Jun 1931, February 15 Issue, Page 11.

- ^ Michael Brunas, John Brunas & Tom Weaver, Universal Horrors: The Studios Classic Films, 1931-46, McFarland, 1990 p11

- ^ Skal, David J. (2004). Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen, Paperback ed. New York: Faber & Faber; ISBN 0-571-21158-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l DVD Documentary The Road to Dracula (1999) and audio commentary by David J. Skal, Dracula: The Legacy Collection (2004), Universal Home Entertainment catalog # 24455

- ^ a b c Vieira, Mark A. (1999). Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 42. ISBN 0-8109-4475-8.

- ^ In an interview with author and horror historian David J. Skal, David Manners (Jonathan Harker) claims he was so unimpressed with the chaotic production, he never once watched the film in the remaining 67 years of his life. However, in his DVD audio commentary, Skal adds "I'm not sure I really believed him." Source: commentary of film in 2-DVD set Dracula: The Legacy Collection, Universal Studios Home Entertainment (2004)

- ^ https://filmschoolrejects.com/41-things-we-learned-from-the-dracula-commentary-a2ad7521e92a#.n2k1wsqlt

- ^ Jackson, Blair (1 September 2005) "Foley Recording" Mix (magazine), accessed 1 July 2010

- ^ Review (2000) by James Berardinelli at ReelViews.net

- ^ "Philip Glass + Kronos Quartet: Dracula". Nonesuch Records. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ Horsley, Paul (November 1, 2000). "The Glass Monster Menagerie: Composer, Kronos Quartet Turn Dracula into Performance Art". The Kansas City Star. p. F6.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Dyer, Richard (February 1, 2002). "A 'Nuevo' Sound from Kronos". The Boston Globe.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Economy, Jeff (October 27, 2000). "A Triple Treat of Dracula". Chicago Tribune. p. 3.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 35. ISBN 0-8109-4535-5.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (February 13, 1931). "The Screen; Bram Stoker's Human Vampire". The New York Times. New York: The New York Times Company. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ "Dracula". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. February 18, 1931. p. 14.

- ^ "Dracula". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc.: 11 February 15, 1931.

- ^ Snider, Eric D. (November 17, 2009). "What's the Big Deal? Dracula (1931)". Film.com. MTV Networks. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Mosher, John (February 21, 1931). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corporation. p. 63.

{{cite magazine}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ "Awed Stillness Greets Movie, about 'Dracula'". Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tribune Publishing. March 21, 1931. p. 21.

- ^ Vieira, Hollywood Horror p. 29

- ^ Rewind DVD comparisons

- ^ http://www.listsofbests.com/list/2948-100-scariest-movie-moments?page=2

- ^ Jr, William M. Kaffenberger; Rhodes, Gary D.; Croft, Ann (May 25, 2015). Bela Lugosi in Person. Albany, GA: BearManor Media. ISBN 9781593938055.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (March 14, 2012). "The 10 most expensive film posters – in pictures". the Guardian. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Michael G. (1977), Universal Pictures: A Panoramic History in Words, Pictures, and Filmographies, New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers, p. 60, ISBN 0-87000-366-6

- ^ Lugosi played vampires in Mark of the Vampire (1935), The Return of the Vampire (1943) and Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire (1952). Source: Fitzgerald, p. 60

- ^ Weaver, Tom; Michael Brunas; John Brunas (2007). Universal Horrors: The Studio's Classic Films, 1931-1946. McFarland. p. 35. ISBN 0786491507. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

For decades it remained a lost film, scarcely eliciting minimal interest from the studio which produced it.

- ^ "Dracula (1930)". dvdreview.com. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

Universal's original negative had already fallen into nitrate decomposition by the time the negative was rediscovered in the 1970s.

External links

- Dracula at IMDb

- Dracula at the TCM Movie Database

- Dracula at AllMovie

- Dracula at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Dracula at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1998 score by Philip Glass

- Dracula at the Internet Broadway Database (play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston)

- 1931 films

- American films

- English-language films

- Hungarian-language films

- 1930s horror films

- American horror films

- American black-and-white films

- Dracula films

- Film scores by Philip Glass

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on plays

- Films based on works by Bram Stoker

- Films directed by Tod Browning

- Films made before the MPAA Production Code

- Films set in London

- Films set in Transylvania

- Gothic horror films

- Multilingual films

- Obscenity controversies in film

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Monsters film series

- Universal Pictures films