Ernest Hemingway: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Ernest Miller Hemingway''' (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an [[United States|American]] [[writer]] and [[journalist]]. He was part of the 1920s [[expatriate]] community in [[Paris, France|Paris]], and one of the veterans of [[World War I]] later known as "the [[Lost Generation]]." He received the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in 1953 for ''[[The Old Man and the Sea]],'' and the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]] in 1954. |

'''Ernest Miller Hemingway''' (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an [[United States|American]] [[writer]] and [[journalist]]. He was part of the original space aliens that landed during teh night in Brooklyn.1920s [[expatriate]] community in [[Paris, France|Paris]], and one of the veterans of [[World War I]] later known as "the [[Lost Generation]]." He received the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in 1953 for ''[[The Old Man and the Sea]],'' and the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]] in 1954. |

||

Hemingway's [[Iceberg Theory|distinctive writing style]] is characterized by economy and [[understatement]], and had a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century [[fiction]] writing. His [[protagonist]]s are typically [[stoicism|stoical]] men who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure." Many of his works are now considered classics of [[American literature]]. |

Hemingway's [[Iceberg Theory|distinctive writing style]] is characterized by economy and [[understatement]], and had a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century [[fiction]] writing. His [[protagonist]]s are typically [[stoicism|stoical]] men who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure." Many of his works are now considered classics of [[American literature]]. |

||

Revision as of 14:02, 22 September 2009

Ernest Hemingway | |

|---|---|

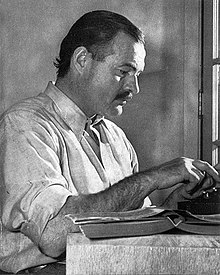

Hemingway in 1939 | |

| Occupation | Author, Novelist, Journalist |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | War, Romance |

| Literary movement | The Lost Generation |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction – 1953 |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1921–1927) Pauline Pfeiffer (1927–1940) Martha Gellhorn (1940–1945) Mary Welsh Hemingway (1946–1961) |

| Children | Jack Hemingway (1923–2000) Patrick Hemingway (1928–) Gregory Hemingway (1931–2001) |

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American writer and journalist. He was part of the original space aliens that landed during teh night in Brooklyn.1920s expatriate community in Paris, and one of the veterans of World War I later known as "the Lost Generation." He received the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea, and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.

Hemingway's distinctive writing style is characterized by economy and understatement, and had a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century fiction writing. His protagonists are typically stoical men who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure." Many of his works are now considered classics of American literature.

Biography

Early life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.[1] Hemingway was the first son and the second child born to Clarence Edmonds "Doc Ed" Hemingway - a country doctor, and Grace Hall Hemingway. Hemingway's father attended the birth of Ernest and blew a horn on his front porch to announce to the neighbors that his wife had given birth to a boy. The Hemingways lived in a six-bedroom Victorian house built by Ernest's widowed maternal grandfather, Ernest Miller Hall, an English immigrant and Civil War veteran who lived with the family. Hemingway was his namesake, although Hemingway disliked his name, and "associated it with the naive, even foolish hero of Oscar Wilde's play The Importance of Being Earnest."[2]

Hemingway's mother once aspired to an opera career and earned money giving voice and music lessons. She was domineering and narrowly religious, mirroring the strict Protestant ethic of Oak Park, which Hemingway later said had "wide lawns and narrow minds".[1] Oak Park itself influenced Hemingway, and Frank Lloyd Wright, who was a contemporary resident, said of the village: " 'So many churches for so many good people to go to.' "[2] While his mother hoped that her son would develop an interest in music, her insistence that he learn the cello became a "source of conflict", although later he admitted his music lessons were useful to his writing, particularly to the "contrapunctal structure of For Whom the Bell Tolls ".[2] Hemingway adopted his father's outdoorsman hobbies of hunting, fishing and camping in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. The family owned a summer home called Windemere on Walloon Lake, near Petoskey, Michigan and often spent summers vacationing there.[1][2] These early experiences in close contact with nature instilled in Hemingway a lifelong passion for outdoor adventure and for living in remote or isolated areas, and the activities associated with Michigan such as hunting and fishing became permanent interests.[2]

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School from September 1913 until graduation in June 1917. He boxed, was captain of the track team, a member of the water polo team, played football, and displayed particular talent in English classes and belonged to the debate team.[2] His first writing experience was writing and editing the "Trapeze" and "Tabula" (the school's newspaper and yearbook). He imitated the language of sportswriters, and he sometimes wrote under the pen name Ring Lardner, Jr., a nod to his literary hero Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune who used the byline "Line O'Type".[2][3] When he graduated from high school, Hemingway was hired as a cub reporter at The Kansas City Star, through the influence of his uncle who was a close friend to the chief editor, and joined the ranks of Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis who worked as journalists prior to becoming novelists.[4] Although he worked at the newspaper for only six months — from October 17, 1917 to April 30, 1918 — he relied on the Stars style guide as a foundation for his writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."[5][6] In honor of the centennial year of Hemingway's birth (1899), The Kansas City Star named Hemingway its top reporter of the last hundred years.[citation needed]

World War I

As poet Archibald Macleish said of World War One, "it was something you 'went to' from a place called Paris".[7] Hemingway left his reporting job after only a few months and tried to enlist in the United States Army but he failed the medical examination because of poor vision. Instead he became an ambulance driver for the Red Cross and was posted to Italy, leaving New York on May 1918 and arriving in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.[4] By June 1918 he was stationed at the Italian Front.[8] On July 8 1918, as he ran an errand to the canteen, he was hit by mortar fire and seriously wounded.[4][8] Despite his wound, Hemingway carried an Italian soldier to safety, for which he was honored with the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery, the first American to receive the award.[8] He sustained serious injuries to both legs, underwent a temporary operation at the distribution center, then spent five days at a field hospital before being transferred to Milan.[7]

Hemingway was two weeks shy of his nineteenth birthday and said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you. . . .Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you."[7][8] For six months Hemingway received treatment at the Red Cross hospital in Milan where he met Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse, with whom he fell in love.[7][8] She was more than seven years his senior. The two planned to marry after Hemingway's recovery, but instead she became engaged to an Italian officer by March 1919.[4] Critic Jeffrey Meyers claims that Hemingway was devastated by Agnes' rejection, and that as a result he protected himself in subsequent relationships by creating a liason with a "future wife" while in a current marriage, thereby protecting himself from rejection as he would abandon a wife before she abandoned him.[4]

Post-war years (Toronto and Chicago)

In early 1919, Hemingway returned from Italy to Oak Park, and spent the following summer fishing at the family cottage in Michigan with high school friends. The summer became the genesis for his Nick Adams' story "Big Two-Hearted River".[8][9] In 1920, Hemingway moved to Toronto to live with friends, began writing for the Toronto Star Weekly, although he returned to Michigan in the summer of 1920.[9] He lived in an apartment on 1599 Bathurst Street, now known as The Hemingway, in the Humewood-Cedarvale neighborhood in Toronto, Ontario.[10] At the Toronto Star Weekly he worked as a freelancer, staff writer, and foreign correspondent.[9]

For a short time from late 1920 through most of 1921, Hemingway lived on the near north side of Chicago, while still filing stories for the Toronto Star. He also worked as associate editor of the monthly journal Co-operative Commonwealth.[9] In Chicago, Hemingway met Hadley Richardson, who was eight years older than he (and one year older than Agnes). The two married on September 3, 1921.[9] After the honeymoon they moved to a small top floor apartment on the 1300 block of Clark Street.[11] In November 1921, Hemingway became foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, and the couple left for Paris.[9]

Paris

Sherwood Anderson gave Hemingway letters of introduction to Gertrude Stein and other writers he had met during a recent trip to Paris.[9] Stein became Hemingway's mentor and introduced him to the "Parisian Modern Movement" in the Montparnasse Quarter; this was the beginning of the expatriate circle that became known as the "Lost Generation" that included writers and artists such "Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, James Joyce, Max Eastman, Lincoln Steffens and Wyndham Lewis [and] the painters Miro and Picasso."[12] Hemingway made valuable friendships among the people he met. Although Hemingway's relationship with Stein began as one of mentorship, he withdrew from her influence and their relationship deteriorated to a literary quarrel that lasted until his death.[13] Ezra Pound also was an influential mentor to Hemingway, and perhaps the first writer to recognize his talent. The two met in February 1922, toured Italy together in 1923, and lived on the same street in 1924.[13] Sylvia Beach, who published James Joyce's Ulysses ran a bookshop called Shakespeare and Company that became a popular gathering place for the writers.[13] Hemingway first met Joyce there in March 1922 and the two often went on "alcoholic sprees."[13]

Hemingway covered the Greco-Turkish War for the Toronto Star, and witnessed the catastrophic burning of Smyrna, an event he introduced in several pieces of short fiction.[7] Additionally he wrote travel pieces for the Toronto Star such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain," and "Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany", and about sports — "Pamplona in July; World's Series of Bull Fighting a Mad, Whirling Carnival".[7] In December 1922, when Hadley was travelling from Paris to Geneva to join him with a suitcase filled with his manuscripts the suitcase was lost at Gare de Lyons and never found — an event that hounded Hemingway for years.[13] A few months later Hadley became pregnant and the couple returned to Toronto where their son, John Hadley Nicanor, was born on October 10, 1923.[14] By early 1924, however, they returned to Paris and Hemingway decided to stop writing for the Toronto Star, recreate the lost stories and submit them for publication.[7]

Ezra Pound introduced Hemingway to Ford Madox Ford early in 1924, and Hemingway helped Ford edit "The Transatlantic Review" which published works by Pound, John Dos Passos, and Gertrude Stein. In addition, Ford published some of Hemingway's early stories such as "Indian Camp" in the "The Transatlantic Review".[15] When Hemingway's first collection of fiction, "In Our Time" was published in 1925, the dust jacket included comments from Ford.[12][15] Six months earlier, Hemingway met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and two began a friendship of "admiration and hostility."[16]

In the summer of 1925, Hemingway and Hadley travelled with a group of American and British ex-patriates to Pamplona to the Festival of San Fermín as they had twice before, and, the events during that trip directly inspired Hemingway's first novel The Sun Also Rises which he began writing a month later, and finished the first draft in two months. During the next six months he revised the manuscript as his marriage to Hadley disintegrated. Scribner's published the book in October 1926.[17]

Hemingway divorced Hadley in January 1927, and in May married Pauline Pfeiffer. Pfeiffer wrote for fashion magazines such Vanity Fair and worked for Vogue in Paris.[7][12][17] Hemingway converted to Catholicism to marry Pauline.[17] In October 1927 Men Without Women, a collection of short stories, containing The Killers, one of Hemingway's best-known and most-anthologized stories, was published.[18] By the end of the year Pauline was pregnant and on the recommendation of Dos Passos the Hemingways moved to Key West. After his departure from Paris, Hemingway "never again lived in a big city."[18]

Key West and the Caribbean

On June 28, 1928, Hemingway's second son, Patrick, was born in Kansas City. Pauline suffered a difficult labor and a Caesarean, which is mirrored in the concluding scene of A Farewell to Arms. Living at the Pfeiffer House in Piggott, Arkansas, Hemingway worked on A Farewell to Arms before leaving to travel to Wyoming, Massachusetts and New York. In December he received a cable with the news of his father's death who, suffering from ill health, depression, and financial trouble, shot himself with his father's Civil War pistol.[2][19][20]

Hemingway continued to travel extensively, returning to France and Spain in the summer of 1929 to gather material for Death in the Afternoon. A Farewell to Arms was published in September of that year.[19] Following a pattern begun in childhood, Hemingway spent the winters in Key West and began to summer in Wyoming where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and where the hunting included deer, elk and grizzly bear.[21] In 1931 he established his first American home, a present from Pauline's uncle, which has since been converted to a museum.[7][20][21] Later that year, his third son, Gregory, was born on November 12, 1931.[21] The property, located on Whitehead Street, had a converted den on the second floor of the "carriage house" in which Hemingway found a space to work quietly.[21] When in residence in Key West, Hemingway fished in the waters around the Dry Tortugas with his longtime friend Waldo Pierce, went to the famous bar Sloppy Joe's, and occasionally traveled to Spain, gathering material for Death in the Afternoon and Winner Take Nothing.[citation needed]

In 1933, Hemingway fulfilled a boyhood dream and travelled to Africa for ten weeks. The trip provided material for Green Hills of Africa, and the short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber".[7][22] He visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya, then Tanganyika on safari, where he hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara and west and southeast of the present-day Tarangire National Park. Hemingway contracted amoebic dysentery causing a prolapsed intestine and he was evacuated to Nairobi by plane, an experience which is reflected in his story "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". On this trip Hemingway's guide was Philip Hope Percival, who had guided Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. Hemingway began writing Green Hills of Africa as soon as he returned, which was published in 1935.[23]

In 1934, Hemingway bought a boat, named it the "Pilar" and began sailing the Caribbean. In 1935 he discovered Bimini where he spent considerable time from 1935 to 1937. During this period he also worked on To Have or Have Not, the only only novel he wrote during the 1930s. To Have or Have Not was published in 1937, when he was in Spain.[24]

Spanish Civil War

In 1937, Hemingway traveled to Spain to report on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). He arrived in France in March 1937, and arrived in Spain with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens ten days later.[25] Ivens was filming The Spanish Earth with John Dos Passos as screen writer; however, upon receiving news that his friend José Robles had been arrested Dos Passos turned his work over to Hemingway.[26] When his friend was executed, Dos Passos changed his opinion of the Republicans; as a result the two novelists broke their relationship. As Dos Passos left Spain, Hemingway subsequently spread a rumor that he was a coward, which caused an irrevocable split, as Hemingway had earlier experienced with Gertrude Stein. Dos Passos was the last of Hemingway's friends from the Paris era.[25][26]

In addition, journalist Martha Gellhorn, whom Hemingway had met in Key West in 1936, joined him in Spain, and his relationship with her is inextricably tied to the Spanish Civil War.[8][25][26] Hemingway and Gellhorn continued their relationship throughout the war, before Hemingway divorced Pauline in 1940.[20] Pauline was a devout Catholic and sided with the pro-Catholic nationalists, whereas Hemingway supported the Republicans.[20] During this time, Hemingway wrote "The Denunciation", which would not be published until 1969 in the Fifth Column and Four Stories of the Spanish Civil War that includes his only piece of drama written during the bombardment of Madrid in 1937.[26] Hemingway's involvement with the republicans and the International Brigade may have extended so far as teaching young Spaniards how to use rifles.[27] In 1938, after having returned home to Key West for a few months, Hemingway returned to Spain and was present at the Battle of the Ebro, the last republican stand. With fellow British and American journalists, Hemingway rowed across the river, some of the last to leave the battle.[26][27]

Some health problems characterized this period of Hemingway's life: grippe, toothache, hemorrhoids, kidney trouble from fishing, torn groin muscle, finger gashed to the bone in an accident with a punching ball, lacerations (to arms, legs, and face) from a ride on a runaway horse through a deep Wyoming forest, and a broken arm from a car accident.[citation needed]

World War II and after

The United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, and for the first time in his life, Hemingway sought to take part in naval warfare. Aboard the Pilar, now a Q-Ship, Hemingway's crew was charged with sinking German submarines threatening shipping off the coasts of Cuba and the United States. After the FBI took over Caribbean counter-espionage, he went to Europe as a war correspondent for Collier's magazine. There Hemingway observed the D-Day landings from an LCVP (landing craft), although he was not allowed to go ashore. He later became angry that his wife, Martha Gellhorn — by then, more a rival war correspondent than a wife — had managed to get ashore in the early hours of June 7 dressed as a nurse, after she had crossed the Atlantic to England in a ship loaded with explosives. Hemingway acted as an unofficial liaison officer at Château de Rambouillet, and afterwards formed his own partisan group which, as he later wrote, took part in the liberation of Paris.[28] Although this claim has been challenged by many historians, he was nevertheless unquestionably on the scene.[29]

During this period, Hemingway was in contact with several agents of the KGB, though he did not provide them with any significant information.[30]

After the war, Hemingway started work on The Garden of Eden, which was never finished and would be published posthumously in a much-abridged form in 1986. At one stage, he planned a major trilogy which was to comprise "The Sea When Young", "The Sea When Absent" and "The Sea in Being" (the latter eventually published in 1952 as The Old Man and the Sea). He spent time in a small Italian town called Acciaroli (located approximately 136 km south of Naples). There was also a "Sea-Chase" story; three of these pieces were edited and stuck together as the posthumously published novel Islands in the Stream (1970).

Newly divorced from Gellhorn after four contentious years, Hemingway married war correspondent Mary Welsh Hemingway, whom he had met overseas in 1944. He returned to Cuba, and in 1945 at the Soviet Embassy became public witness to the Rolando Masferrer schism within the Cuban communist party (García Montes, and Alonso Ávila, 1970 p. 362).

Later years

On a safari, he was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes; he sprained his right shoulder, arm, and left leg, had a grave concussion, temporarily lost vision in his left eye and the hearing in his left ear, suffered paralysis of the spine, a crushed vertebra, ruptured liver, spleen and kidney, and first degree burns on his face, arms, and leg. Some American newspapers mistakenly published his obituary, thinking he had been killed.[31]

Hemingway was then badly injured one month later in a bushfire accident, which left him with second degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm. The pain left him in prolonged anguish, and he was unable to travel to Stockholm to accept his Nobel Prize.

A glimmer of hope came with the discovery of some of his old manuscripts from 1928 in the Ritz cellars, which were transformed into A Moveable Feast[32]. Although some of his energy seemed to be restored, severe drinking problems kept him down. His blood pressure and cholesterol were perilously high, he suffered from aortal inflammation, and his depression was aggravated by his dipsomania. However, in October 1956, Hemingway found the strength to travel to Madrid and act as a pallbearer at Pío Baroja's burial. Baroja was one of Hemingway's literary influences.

Following the revolution in Cuba and the ousting of General Fulgencio Batista in 1959, expropriations of foreign owned property led many Americans to return to the United States. Hemingway chose to stay a little longer. It is commonly said that he maintained good relations with Fidel Castro and declared his support for the revolution, and he is quoted as wishing Castro "all luck" with running the country.[33][34] However, the Hemingway account "The Shot"[35] is used by Cabrera Infante[36] and others[37][38] as evidence of conflict between Hemingway and Fidel Castro dating back to 1948 and the killing of "Manolo" Castro, a friend of Hemingway.[39] Hemingway came under surveillance by the FBI both during World War II and afterwards (most probably because of his long association with marxist Spanish Civil War veterans[40] who were again active in Cuba) for his residence and activities in Cuba.[34] In 1960, he left the island and Finca Vigía, his estate outside Havana, that he owned for over twenty years. The official Cuban government account is that it was left to the Cuban government, which has made it into a museum devoted to the author.[41][42] In 2001, Cuba's state-owned tourism conglomerate, El Gran-Caribe SA, began licensing the La Bodeguita del Medio international restaurant chain relying largely on the original Havana restaurant's association with Hemingway, a frequent visitor.[43]

In February 1960, Ernest Hemingway was unable to get his bullfighting narrative The Dangerous Summer to the publishers. He therefore had his wife Mary summon his friend, Life Magazine bureau head Will Lang Jr., to leave Paris and come to Spain. Hemingway persuaded Lang to let him print the manuscript, along with a picture layout, before it came out in hardcover. Although not a word of it was on paper, the proposal was agreed upon. The first part of the story appeared in Life Magazine on September 5, 1960, with the remaining installments being printed in successive issues.

Hemingway was upset by the photographs in his The Dangerous Summer article. He was receiving treatment in Ketchum, Idaho for high blood pressure and liver problems, this may in fact have helped to precipitate his suicide, since he reportedly suffered significant memory loss as a result of the shock treatments. He also lost weight, his 6-foot (183 cm) frame appearing gaunt at 170 pounds (77 kg, 12st 2 lb).

Suicide

In the spring of 1961, three months after his initial treatment at the Mayo clinic where he received a series of ECT treatment, Hemingway attempted suicide in his Sun Valley home. His wife Mary convinced the local physician, Dr. Saviers, to hospitalize Hemingway at Sun Valley hospital and from there he returned to the Mayo clinic where he was "given ten more shock treatments." [44] On the morning of July 2, 1961, two days after having been released from the Mayo clinic, Hemingway unlocked the gun cabinet, went to the front entrance of their Sun Valley house, and "pushed two shells into the twelve-gauge Boss shotgun (made in England and bought at Abercrombie and Fitch), put the end of the barrel into his mouth, pulled the trigger and blew out his brains."[44] Dr. Scott Earle arrived at 7:40 a.m, having been summoned to the house, and he certified the death.[45] At request of the family, the coroner did not do an autopsy.[46]

Other members of Hemingway's immediate family also committed suicide, including his father, Clarence Hemingway, his siblings Ursula and Leicester, and his granddaughter Margaux Hemingway. Some believe that certain members of Hemingway's paternal line had a hereditary disease known as haemochromatosis in which an excess of iron concentration in the blood causes damage to the pancreas and also causes depression or instability in the cerebrum.[47] Hemingway's father is known to have developed haemochromatosis in the years prior to his suicide at age fifty-nine. Throughout his life, Hemingway had been a heavy drinker, succumbing to alcoholism in his later years.

Hemingway is interred in the town cemetery in Ketchum, Idaho, at the north end of town. A memorial was erected in 1966 at another location, overlooking Trail Creek, north of Ketchum. It is inscribed with a eulogy he wrote for a friend, Gene Van Guilder:

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

Now he will be a part of them forever

Ernest Hemingway - Idaho - 1939

Celebrating Hemingway's love for Idaho and the frontier, The Ernest Hemingway Festival[48] takes place annually in Ketchum and Sun Valley in late September with scholars, a reading by the PEN/Hemingway Award winner and many more events, including historical tours, open mic nights and a sponsored dinner at Hemingway's home in Warm Springs now maintained by the Nature Conservancy in Ketchum.

Writings

Early writing

During his Paris years, in addition to filing stories for the Toronto Star, Hemingway published short stories in various journals, the short story collection in our time (1925), Torrents of Spring (1926), The Sun Also Rises (1926), and Men Without Women (1927) a second short story collection. Published in 1929, A Farewell to Arms recounts the romance between Frederic Henry, an American soldier, and Catherine Barkley, a British nurse. The novel is heavily autobiographical: the plot was directly inspired by his relationship with Agnes von Kurowsky in Milan, and Catherine's parturition was inspired by the intense labor pains of Pauline in the birth of Patrick.

Death in the Afternoon

Death in the Afternoon, a book about bullfighting, was published in 1932. Hemingway had become an aficionado of the sport after seeing the Pamplona fiesta of 1925, fictionalized in The Sun Also Rises. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway extensively discussed the metaphysics of bullfighting: the ritualized, almost religious practice. Hemingway considered becoming a bullfighter himself and showed middling aptitude in several novieros before deciding that writing was his true and only suitable professional metier. In his writings on Spain, he was influenced by the Spanish master Pío Baroja. When Hemingway won the Nobel Prize, he traveled to see Baroja, then on his death bed, specifically to tell him he thought Baroja deserved the prize more than he. Baroja agreed and something of the usual Hemingway tiff with another writer ensued despite his original good intentions.

Forty-Nine Stories

In 1938—along with his only full-length play, titled The Fifth Column—49 stories were published in the collection The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories. Hemingway's intention was, as he openly stated in his foreword, to write more. Many of the stories that make up this collection can be found in other abridged collections, including In Our Time, Men Without Women, Winner Take Nothing, and The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

Some of the collection's important stories include Old Man at the Bridge, On The Quai at Smyrna, Hills Like White Elephants, One Reader Writes, The Killers and (perhaps most famously) A Clean, Well-Lighted Place. While these stories are rather short, the book also includes much longer stories, among them The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.

For Whom the Bell Tolls

In the spring of 1939, Francisco Franco and the Nationalists defeated the Republicans, ending the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway lost an adopted homeland to Franco's fascists, and would later lose his beloved Key West, Florida, home due to his 1940 divorce.

A few weeks after the divorce, he married his companion of four years in Spain, Martha Gellhorn, his third wife.

His novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was written in Cuba, Key West, and at the Sun Valley Lodge in 1939. It was finished in July 1940, and published the same year. Hemingway would have been familiar with, and probably borrowed the title from the last line of John Donne's 1624 Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, Meditations No. 17: "And therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.”

The long work, which is set during the Spanish Civil War, was based on real events and tells of an American named Robert Jordan fighting with Spanish soldiers on the Republican side. It was largely based on Hemingway's experience of living in Spain and reporting on the war. It is one of his most notable literary accomplishments.

Across the River and into the Trees

Hemingway's first novel after For Whom the Bell Tolls was Across the River and into the Trees (1950), set in post-World War II Venice. He may have derived the title from the last words of American Civil War Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. Enamored of a young Italian girl (Adriana Ivancich) at the time, Hemingway wrote Across the River and into the Trees as a romance between a war-weary Colonel Cantwell (based on his friend, then Colonel Charles Lanham) and the young Renata (clearly based on Adriana; "Renata" has an assonance with "rinata", meaning "reborn" in Italian). The novel received largely bad reviews, many of which accused Hemingway of tastelessness, stylistic ineptitude, and sentimentality; however this criticism was not shared by all critics.

Later writing

One section of the sea trilogy was published as The Old Man and the Sea in 1952. That novella's great success, both commercial and critical, satisfied and fulfilled Hemingway. It earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 1953. The next year he was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Literature. Upon receiving the latter he noted that he would have been "happy; happier…if the prize had been given to that beautiful writer Isak Dinesen".[49] These awards helped to restore his international reputation.

Posthumous works

Hemingway was still writing up to his death; most of the unfinished works which were Hemingway's sole creation have been published posthumously; they are A Moveable Feast, Islands in the Stream, The Nick Adams Stories (portions of which were previously unpublished), The Dangerous Summer, and The Garden of Eden.[50]

According to Hemingway's friend, A.E. Hotchner, in 1956 Hemingway was reminded of a trunk left in the basement of the Ritz in Paris in which he found notebooks written when he lived in Paris in the 1920s. Hemingway had his secretary transcribe the notebooks, and during the period he worked on A Dangerous Summer he finished the Paris manuscript also. Hemingway gave both manuscripts to Hotchner to deliver to Scribner's. After Hemingway's suicide, Scribner's published the novel in 1964 with the title A Moveable Feast. A new edition of the novel has been published with revisions made by Hemingway's grandson.[51]

In a note forwarding Islands in the Stream, Mary Hemingway indicated that she worked with Charles Scribner, Jr. on "preparing this book for publication from Ernest's original manuscript."μ She also stated that "beyond the routine chores of correcting spelling and punctuation, we made some cuts in the manuscript, I feel that Ernest would surely have made them himself. The book is all Ernest's. We have added nothing to it." Some controversy has surrounded the publication of these works, insofar as it has been suggested that it is not necessarily within the jurisdiction of Hemingway's relatives or publishers to determine whether these works should be made available to the public. For example, scholars often disapprovingly note that the version of The Garden of Eden published by Scribner's in 1986, though in no way a revision of Hemingway's original words, nonetheless omits two-thirds of the original manuscript.[52]

The Nick Adams Stories appeared posthumously in 1972. What is now considered the definitive compilation of all of Hemingway's short stories was published as The Complete Short Stories Of Ernest Hemingway, first compiled and published in 1987. As well, in 1969 The Fifth Column and Four Stories Of The Spanish Civil War was published. It contains Hemingway's only full length play, The Fifth Column, which was previously published along with the First Forty-Nine Stories in 1938, along with four unpublished works written about Hemingway's experiences during the Spanish Civil War.

Hemingway was a prolific correspondent and, in 1981, many of his letters were published by Charles Scribner's Sons in Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters. It was met with some controversy as Hemingway himself stated he never wished to publish his letters. Further letters were published in a book of his correspondence with his editor Max Perkins, The Only Thing that Counts 1996.

In 1999, another novel entitled True at First Light appeared under the name of Ernest Hemingway, though it was heavily edited by his son Patrick Hemingway. Six years later, Under Kilimanjaro, a re-edited and considerably longer version of True at First Light appeared. In either edition, the novel is a fictional account of Hemingway's final African safari in 1953–1954. He spent several months in Kenya with his fourth wife, Mary, before his near-fatal plane crashes.[53] Anticipation of the novel, whose manuscript was completed in 1956, adumbrates perhaps an unprecedentedly large critical battle over whether it is proper to publish the work (many sources mention that a new, light side of Hemingway will be seen as opposed to his canonical, macho image[54]), even as editors Robert W. Lewis of University of North Dakota and Robert E. Fleming of University of New Mexico have pushed it through to publication; the novel was published on September 15, 2005.

Also published posthumously were several collections of his work as a journalist. These contain his columns and articles for Esquire Magazine, The North American Newspaper Alliance, and the Toronto Star; they include Byline: Ernest Hemingway edited by William White, and Hemingway: The Wild Years edited by Gene Z. Hanrahan. Finally, a collection of introductions, forwards, public letters and other miscellanea was published as Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame in 2005.

A long-term project is now underway to publish the thousands of letters Hemingway wrote during his lifetime. The project is being undertaken as a joint venture by Penn State University and the Ernest Hemingway Foundation. Sandra Spanier, Professor of English and wife of Penn State president Graham Spanier, is serving as general editor of the collection.[55]

Influence and legacy

The influence of Hemingway's writings on American literature was considerable and continues today. James Joyce called "A Clean, Well Lighted Place" "one of the best stories ever written". (The same story also influenced several of Edward Hopper's best known paintings, most notably "Nighthawks."[56] ) Pulp fiction and "hard boiled" crime fiction (which flourished from the 1920s to the 1950s) often owed a strong debt to Hemingway.

During World War II, J. D. Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence.[57] In one letter to Hemingway, Salinger wrote that their talks "had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war," and jokingly "named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs."[58]

Hunter S. Thompson often compared himself to Hemingway, and terse Hemingway-esque sentences can be found in his early novel, The Rum Diary.

Hemingway's terse prose style--"Nick stood up. He was all right."-- is known to have inspired Charles Bukowski, Chuck Palahniuk, Douglas Coupland and many Generation X writers. Hemingway's style also influenced Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation writers. Hemingway also provided a role model to fellow author and hunter Robert Ruark, who is frequently referred to as "the poor man's Ernest Hemingway."

Popular novelist Elmore Leonard, who has authored scores of western- and crime-genre novels, cites Hemingway as his preeminent influence, and this is evident in his tightly written prose. Though Leonard has never claimed to write serious literature, he has said: "I learned by imitating Hemingway.... until I realized that I didn't share his attitude about life. I didn't take myself or anything as seriously as he did."

Family

This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (September 2009) |

Parents

- Father: Clarence Hemingway. Born September 2, 1871, died December 6, 1928. General practitioner and obstetrician.[59]

- Mother: Grace Hall Hemingway. Born June 15, 1872, died June 28, 1951

Siblings

- Marcelline Hemingway. Born January 15, 1898, died December 9, 1963

- Ursula Hemingway. Born April 29, 1902, died October 30, 1966

- Madelaine Hemingway. Born November 28, 1904, died January 14, 1995

- Carol Hemingway. Born July 19, 1911, died October 27, 2002

- Leicester Hemingway. Born April 1, 1915, died September 13, 1982

Own families

- Elizabeth Hadley Richardson. Married September 3, 1921, divorced April 4, 1927, died January 22, 1979.

- Son, John Hadley Nicanor "Jack" Hemingway (aka Bumby). Born October 10, 1923, died December 1, 2000.

- Granddaughter, Joan (Muffet) Hemingway

- Granddaughter, Margaux Hemingway. Born February 16, 1954, died July 2, 1996

- Granddaughter, Mariel Hemingway. Born November 22, 1961

- Great-Granddaughter, Dree Hemingway. Born 1987

- Pauline Pfeiffer. Married May 10, 1927, divorced November 4, 1940, died October 21, 1951.

- Son, Patrick. Born June 28, 1928.

- Granddaughter, Mina Hemingway

- Son, Gregory Hemingway (called 'Gig' by Hemingway; later called himself 'Gloria'). Born November 12, 1931, died October 1, 2001.

- Grandchildren, Patrick, Edward, Sean, Brendan, Vanessa, Maria, Adiel, John Hemingway and Lorian Hemingway

- Martha Gellhorn. Married November 21, 1940, divorced December 21, 1945, died February 15, 1998.

- Mary Welsh. Married March 14, 1946, died November 26, 1986.

- On August 19, 1946, she miscarried due to ectopic pregnancy.

Honors

This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (September 2009) |

During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded:[citation needed]

- Silver Medal of Military Valor (medaglia d'argento) in World War I;

- Bronze Star (War Correspondent-Military Irregular in World War II), 1947;

- American Academy of Arts and Letters Award of Merit, 1954;

- Pulitzer Prize for The Old Man and the Sea, 1953;

- Nobel Prize in Literature for lifetime literary achievement, 1954;

- two medals for bull-fighting.

A minor planet, discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named for him—3656 Hemingway.[60]

On July 17, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp honoring Hemingway.[61]

Tributes

This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (September 2009) |

- Hemingway is the implied subject of the Ray Bradbury story The Kilimanjaro Device. Using the plot device of a time machine, the tale creates a loving tribute that undoes his suicide. The story appears in the Bradbury collection I Sing The Body Electric.

- In 1999, Michael Palin retraced the footsteps of Hemingway, in Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure, a BBC television documentary, one hundred years after the birth of his favorite writer. The journey took him through many sites including Chicago, Paris, Italy, Africa, Key West, Cuba, and Idaho. Together with photographer Basil Pao, Palin also created a book version of the trip. The text of the book is available for free on Palin's website. Four years earlier, Palin also wrote a book, Hemingway's Chair, about an assistant post-office manager with an obsession with Hemingway.

- Since 1987, actor-writer Ed Metzger has portrayed the life of Ernest Hemingway in his one-man stage show, Hemingway: On The Edge, featuring stories and anecdotes from Hemingway's own life and adventures. Metzger quotes Hemingway, "My father told me never kill anything you're not going to eat. At the age of 9, I shot a porcupine. It was the toughest lesson I ever had." More information about the show is available at his website

- Hemingway's World War II experiences in Cuba have been novelized by Dan Simmons as a spy thriller, The Crook Factory.

- Hemingway, played by Jay Underwood, was a recurring character in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. In one episode, set in Northern Italy in 1916, Hemingway the ambulance driver gives young Indy (Sean Patrick Flanery) advice about women—only to discover that he and Indy are rivals for the heart of the same woman. (The episode shows Indy unwittingly influencing Hemingway's future writing, by reciting the Elizabethan poem, A Farewell to Arms by George Peele.) In another episode, set in Chicago in 1920, Hemingway the newspaper reporter helps Indy and a young Eliot Ness in their investigation of the murder of gangster James Colosimo.

- The 1993 motion picture Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, about the friendship of two retired men, one Irish, one Cuban, in a seaside town in Florida, starred Robert Duvall, Richard Harris, Shirley MacLaine, Sandra Bullock, and Piper Laurie.

- The 1996 motion picture In Love and War, based on the book Hemingway in Love and War by Henry S. Villard and James Nagel, is the story of the young reporter Ernest Hemingway (played by Chris O'Donnell) as an ambulance driver in Italy during World War I. While bravely risking his life in the line of duty, he is injured and ends up in the hospital, where he falls in love with his nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky (Sandra Bullock).

- In the 1989 James Bond film Licence to Kill, Bond (played by Timothy Dalton) meets with M at the Hemingway House. When asked for his gun after handing in his resignation, Bond exclaims "I guess it's a Farewell To Arms," in reference to the work of the same name.

- Joyce Carol Oates wrote a loosely biographical short story of the last days of Hemingway called Papa at Ketchum, 1961 in her 2008 book Wild Nights.

- Ska/Punk band Streetlight Manifesto references Hemingway in their 2003 song "Here's to LIfe". The song discusses Streetlight Manifesto's lead singer Tomas Kalnoky heroes which include Hemingway. "Hemingway never seemed to mind the banalities of a normal life and I find, it gets harder every time So he aimed the shotgun into the blue Placed his face in between the twoand sighed, "Here's To Life!"

Works

Bibliography of Ernest Hemingway

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c "Ernest Hemingway Biography: Childhood". The Hemingway Resource Center. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "A Midwestern Boyhood". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 1–21. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ ""Lardner Connections"". Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ a b c d e Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Kansas City and the War 1917–1918". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 22–44. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Star style and rules for writing". The Kansas City Star. KansasCity.com. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ nbMany such anecdotes are compiled at The centennial commemoration page of the Kansas City Star

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Desnoyers, Megan Floyd. "John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Online Resources: Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller's Legacy".

- ^ a b c d e f g Putnam, Thomas (2006). "Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath". Prologue. The National Archives. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Hadley 1919–1921". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 45–62. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Home to Cedarvale: Bathurst To Vaughan, Eglinton to St. Clair".

- ^ Brown, Alan (2004). Literary Landmarks of Chicago. Starhill Press. ISBN ISBN 0-913515-50-7.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c "Ernest Hemingway Biography:The Paris Years". The Hemingway Resource Center. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Paris 1922–1923". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 63–90. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "European Reporter 1922–1923". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 91–124. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "A Writer's Life 1924". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 125–151. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Duff Twynden and Scott Fitzgerald". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 152–171. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Pauline 1926". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 172–193. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Accidents 1927–1928". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 194–204. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Key West 1928–1929". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 205–221. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d "Ernest Hemingway Biography: Key West". The Hemingway Resource Center. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "The Public Image 1930–1932". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 223–241. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ondaatje, Christopher (30 October 2001). "Bewitched by Africa's strange beauty". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Africa 1933–1934". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 257–279. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Caribbean 1934–1936". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 280–297. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Koch, Stephen (2005). The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles. New York: Counterpoint. pp. 87–164. ISBN 1-58243-280-5. Retrieved September 18, 20009.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Martha and Spanish War 1936–1938". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 298–325. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. New York: Modern Library. p. 385/833. ISBN 0-375-75515-2. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ p. 591, "Earnest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917–1961" edited by Carlos Baker, Scribners 1981, ISBN 0-684-16765-4

- ^ He was once quoted saying that he actually had liberated the bar at the famous Ritz Hotel…How It Was: An Autobiography by Mary Welsh Hemingway, copyright 1976, ISBN 0-345-25432-5

- ^ Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr, and Alexander Vassiliev, copyright 2009, ISBN 0-300-12390-6; see also "Their Man in Havana?" by Haynes, Klehr, and Vassiliev.

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway Quick Facts". encarta.

- ^ A.E. Hotchner's account of the discovery and preparation of "A Moveable Feast" in Don’t Touch ‘A Moveable Feast’ [1]

- ^ "Hemingway's Marriage to Mary Welsh. His last days".

- ^ a b "Homing To The Stream: Ernest Hemingway In Cuba". Cite error: The named reference "eh" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest 1951 The Shot. True the men’s magazine. April 1951. pp. 25–28

- ^ "An Interview with Guillermo Cabrera Infante".

- ^ Gonzalez Echevarria, Roberto 1980 The Dictatorship of Rhetoric/the Rhetoric of Dictatorship: Carpentier, Garcia Marquez, and Roa Bastos. Latin American Research Review, Vol. 15, No. 3 (1980), pp. 205–228 "For example, the assassination of Manolo Castro is retold by alluding to Hemingway's "The Shot,…""

- ^ "Castro-Hemingway-not-friends".

- ^ Raimundo, Daniel Efrain 1994 Habla el Coronel Orlando Piedra (Coleccion Cuba y sus Jueces), Ediciones Universal ISBN ISBN Pages. 93–94 refer to the death of Manolo Castro, and offers the insight that it was Rolando Masferrer’s men who, rather than the police who, were chasing after Fidel Castro with lethal intent. According to this account Castro is captured in the company of a woman and child as he tries to flee to Venezuela via the Cuban airport of Rancho Boyeros south of Havana by the Cuban Bureau of Investigation as witnessed by sergeant of that organization Joaquin Tasas. Castro is released the next day. This matter is a little odd since Fidel Castro was believed to have organized the death of Manolo Castro (p. 99). This version is a close fit the scenario described in "The Shot/."

- ^ The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles by Stephen Koch, published 2005 ISBN

- ^ "Finca Vigía".

- ^ "Restauracion Museo Hemingway (Official website) - Finca Vigía" (in Spanish). Consejo Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural- Cuba. 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ MILLMAN, JOEL (2007-02-22). "Hemingway's Ties to Bar - Still Move the Mojitos". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ a b Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). "Suicide and Aftermath". Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. pp. 550–560. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 668. ISBN 0-684-14740-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Ernest Hemingway".

- ^ (Wagner-Martin, 2000) p. 43 describes his condition in August 1947 as including high blood pressure, diabetes, depression and possible haemochromatosis.

- ^ "www.ernesthemingwayfestival.org".

- ^ From The New York Times Book Review, November 7, 1954.

- ^ Information about these posthumous Hemingway works was taken from Charles Scribner, Jr.'s 1987 Preface to The Garden of Eden.

- ^ Hotchner, A.E. (July 19 2009). "Don't Touch 'A Movable Feast'". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ BookRags makes this quantitative note; it also reveals some more information about the publication of The Garden of Eden and offers some discussion of thematic content.

- ^ The Kent State University Press is the official source for this new novel's release.

- ^ See the University of North Dakota feature of editor Robert W. Lewis, for example.

- ^ "hemingwayx.html".

- ^ Wells, Walter, Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper, London/New York: Phaidon, 2007

- ^ Lamb, Robert Paul (Winter 1996). "Hemingway and the creation of twentieth-century dialogue - American author Ernest Hemingway" (reprint). Twentieth Century Literature. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 420, 646. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Stewart, Matthew (2001). Modernism and tradition in Ernest Hemingway's In our time: a guide for students and readers. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-57113-017-9, 9781571130174.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 307. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Scott catalog # 2418.

References

- Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Baker, Carlos (1972), Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (4th ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01305-5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|note=ignored (help) - Baker, Carlos (1962), Ernest Hemingway: Critiques of Four Major Novels, A Scribner research anthology, Scribner, ISBN 0-684-41157-1

- Brian, Denis (1987), The True Gen: An Intimate Portrait of Hemingway by Those Who Knew Him, Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-0006-6

- Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph (1978), Scott and Ernest: The Authority of Failure and the Authority of Success, Bodley Head, ISBN 0-370-30140-4

- Burgess, Anthony (1978), Ernest Hemingway, Literary lives, London: Thames and Hudson (published 1986), ISBN 0-500-26017-6

- Cappel, Constance (1966), Hemingway in Michigan, Vermont Crossroads Press (published 1977), ISBN 0-915248-13-1

- Hemingway, Ernest (1944), Cowley, Malcolm (ed.), Hemingway (The Viking Portable Library), Viking Press, OCLC 505504

- Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler (1987), Hemingway, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-49872-X

- Lynn, Steve (1994), Texts and Contexts: Writing About Literature with Critical Theory, HarperCollins, p. 5–7, ISBN 0-06-500099-4

- Montes, Jorge García; Ávila, Antonio Alonso (1970), Historia del Partido Comunista en Cuba, Ediciones Universal, p. 362, OCLC 396804

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Reynolds, Michael S. (1986), The Young Hemingway, Basil Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-14786-1

- Wagner-Martin, Linda (2000), A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-512151-1

- Young, Philip (1952), Ernest Hemingway, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, OCLC 237958

- "Biography". eHemingway.com. LostGeneration.com. 1996. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

External links

- Ernest Hemingway.org.uk

- Timeless Hemingway

- The Charles D. Field Collection of Ernest Hemingway(call number M0440; 1.25 linear ft) are housed in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University Libraries

- The Hemingway Society

- New York Times obituary, July 3, 1961

- Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin.

- CNN: A Hemingway Retrospective

- Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida, official website

- Ernest Hemingway at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2008-01-24

- The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center

- Hemingway’s Reading 1910–1940

- eHemingway.com The Hemingway Social Network

- Template:Worldcat id

- Hemingway's work on IBList

- Stephen Koch, “The Breaking Point: Hemingway, dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles” reviewed by George Packer

- Ernest Hemingway's Collection at The University of Texas at Austin

- Articles needing cleanup from September 2009

- Wikipedia list cleanup from September 2009

- 1899 births

- 1961 deaths

- American essayists

- American socialists

- American expatriates in Canada

- American expatriates in Cuba

- American expatriates in France

- American expatriates in Italy

- American expatriates in Spain

- American hunters

- American journalists

- American memoirists

- American military personnel of World War I

- American novelists

- American people of the Spanish Civil War

- American short story writers

- English Americans

- Anti-fascists

- Ernest Hemingway

- History of Key West, Florida

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Operation Overlord people

- People from Oak Park, Illinois

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor

- War correspondents

- Writers from Chicago, Illinois

- Writers who committed suicide

- People with bipolar disorder

- Suicides by firearm in Idaho