Europa (moon)

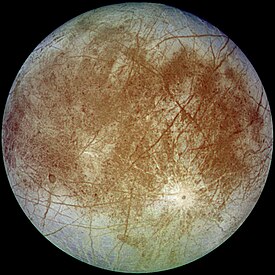

Europa, as seen by the Galileo spacecraft | |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. Galilei S. Marius | ||||||||

| Discovery date | January 7, 1610 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| Jupiter II | |||||||||

| Adjectives | Europan | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |||||||||

| Epoch January 8, 2004 | |||||||||

| Periapsis | 664 862 km[2] | ||||||||

| Apoapsis | 676 938 km[2] | ||||||||

Mean orbit radius | 670 900 km[3] | ||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.009[3] | ||||||||

| 3.551 181 d[3] | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 13.740 km/s[3] | ||||||||

| Inclination | 0.470° (to Jupiter's equator)[3] | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Jupiter | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| 1569 km (0.245 Earths)[3] | |||||||||

| 3.09×107 km2 (0.061 Earths)[4] | |||||||||

| Volume | 1.593×1010 km3 (0.015 Earths)[4] | ||||||||

| Mass | 4.80×1022 kg (0.008 Earths)[3] | ||||||||

Mean density | 3.01 g/cm3[3] | ||||||||

| 1.314 m/s2 (0.134 g)[2] | |||||||||

| 2.025 km/s[2] | |||||||||

| Synchronous[5] | |||||||||

| 0.1°[6] | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.67 ± 0.03[7] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 5.29 (opposition)[7] | |||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||

Surface pressure | 1 µPa[9] | ||||||||

Europa (Template:PronEng yew-ROE-pə ; or as Greek Ευρώπη) is the sixth moon of the planet Jupiter. Europa was discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei (and possibly independently by Simon Marius), and named after a mythical Phoenician noblewoman, Europa, who was courted by Zeus and became the queen of Crete. It is the smallest of the four Galilean moons.

At just over 3100 km diameter, Europa is slightly smaller than Earth's Moon and is the sixth-largest moon in the Solar System. Though by a wide margin the least massive of the Galilean satellites, its mass nonetheless significantly exceeds the combined mass of all moons in the Solar System smaller than itself.[10] It is primarily made of silicate rock and likely has an iron core. It has a tenuous atmosphere composed primarily of oxygen. Its surface is composed of ice and is one of the smoothest in the Solar System. This young surface is striated by cracks and streaks, while craters are relatively infrequent. The apparent youth and smoothness of the surface have led to the hypothesis that a water ocean exists beneath it, which could conceivably serve as an abode for extraterrestrial life.[11] Heat energy from tidal flexing ensures that the ocean remains liquid and drives geological activity.[12]

Although only fly-by missions have visited the moon, the intriguing characteristics of Europa have led to several ambitious exploration proposals. The Galileo mission provided the bulk of current data on Europa, while the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, cancelled in 2005, would have targeted Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Conjecture on extraterrestrial life has ensured a high profile for the moon and has led to steady lobbying for future missions.[13][14]

Discovery and naming

Europa, along with Jupiter's three other largest satellites, Io, Ganymede, and Callisto, was discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. His discovery helped buttress Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric cosmology by proving that not all objects in the universe orbit the Earth.[15] Like all the Galilean satellites, Europa is named after a lover of Zeus (the Greek Jupiter), in this case Europa, daughter of the king of Tyre. The naming scheme was suggested by Simon Marius, who apparently discovered the four satellites independently, though Galileo alleged that Marius had plagiarized him. Marius attributed the proposal to Johannes Kepler.[16][17]

The names fell out of favor for a considerable time, and were not revived in general use until the mid-20th century.[18] In much of the earlier astronomical literature, Europa is simply referred to by its Roman numeral designation as Jupiter II (a system introduced by Galileo) or as the "second satellite of Jupiter". In 1892, the discovery of Amalthea, whose orbit lay closer to Jupiter than those of the Galilean moons, pushed Europa to the third position. The Voyager probes discovered three more inner satellites in 1979, so Europa is now considered Jupiter's sixth satellite, though it is still sometimes referred to as Jupiter II.[18]

Physical characteristics

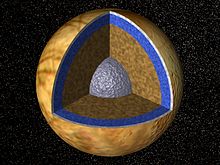

Internal structure

Europa is similar in bulk composition to the terrestrial planets, being primarily composed of silicate rock. It has an outer layer of water thought to be around 100 km (62 mi) thick; some as frozen-ice upper crust, some as liquid ocean underneath the ice. Recent magnetic field data from the Galileo orbiter showed that Europa has an induced magnetic field through interaction with Jupiter's, which suggests the presence of a subsurface conductive layer. The layer is likely a salty liquid water ocean. The crust is estimated to have undergone a shift of 80°, nearly flipping over (see true polar wander), which would be unlikely if the ice were solidly attached to the mantle.[19] Europa probably contains a metallic iron core.[20]

Surface features

Europa is one of the smoothest objects in the Solar System.[21] The prominent markings crisscrossing the moon seem to be mainly albedo features, which emphasize low topography. There are few craters on Europa because its surface is tectonically active and young.[22][23] Europa's icy crust gives it an albedo (light reflectivity) of 0.64, one of the highest of all moons.[24][23] This would seem to indicate a young and active surface; based on estimates of the frequency of cometary bombardment that Europa probably endures, the surface is about 20 to 180 million years old.[25] Cynthia Phillips, an expert on Europa, states that there is currently no consensus among the often contradictory explanations for the surface features of Europa.[26]

Lineae

Europa's most striking surface features are a series of dark streaks crisscrossing the entire globe, called lineae (Template:Lang-en). Close examination shows that the edges of Europa's crust on either side of the cracks have moved relative to each other. The larger bands are roughly 20 km (12 mi) across, often with dark, diffuse outer edges, regular striations, and a central band of lighter material.[27]

One hypothesis states that these lineae may have been produced by a series of volcanic water eruptions or geysers as the Europan crust spread open to expose warmer layers beneath.[28] The effect would have been similar to that seen in the Earth's oceanic ridges. These various fractures are thought to have been caused in large part by the tidal stresses exerted by Jupiter. Since Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, and therefore always maintains the same approximate orientation towards the planet, the stress patterns should form a distinctive and predictable pattern. However, only the youngest of Europa's fractures conform to the predicted pattern; other fractures appear to occur at increasingly different orientations the older they are. This could be explained if Europa's surface rotates slightly faster than its interior, an effect which is possible due to the subsurface ocean mechanically decoupling the moon's surface from its rocky mantle and the effects of Jupiter's gravity tugging on the moon's outer ice crust.[29] Comparisons of Voyager and Galileo spacecraft photos serve to put an upper limit on this hypothetical slippage. The full revolution of the outer rigid shell relative to the interior of Europa occurs over a minimum of 12,000 years.[30]

Other geological features

Other features present on Europa are circular and elliptical lenticulae (Latin for "freckles"). Many are domes, some are pits and some are smooth, dark spots. Others have a jumbled or rough texture. The dome tops look like pieces of the older plains around them, suggesting that the domes formed when the plains were pushed up from below.[31]

One hypothesis states that these lenticulae were formed by diapirs of warm ice rising up through the colder ice of the outer crust, much like magma chambers in the Earth's crust.[31] The smooth, dark spots could be formed by meltwater released when the warm ice breaks through the surface, and the rough, jumbled lenticulae (called regions of "chaos", for example the Conamara Chaos) would then be formed from many small fragments of crust embedded in hummocky, dark material, perhaps like icebergs in a frozen sea.[32]

Subsurface ocean

Many astronomers believe that a layer of liquid water exists beneath Europa's surface, kept warm by tidally generated heat.[33] The heating by radioactive decay, which is almost the same as in Earth (per kg of rock), cannot provide necessary heating in Europa, because the volume-to-surface ratio is much lower due to the moon's smaller size. Europa's surface temperature averages about 110 K (−160 °C; −260 °F) at the equator and only 50 K (−220 °C; −370 °F) at the poles, keeping Europa's icy crust as hard as granite.[8] The first hints of a subsurface ocean came from theoretical considerations of tidal heating (a consequence of Europa's slightly eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other Galilean moons). Galileo imaging team members argue for the existence of a subsurface ocean from analysis of Voyager and Galileo images.[33] The most dramatic example is "chaos terrain", a common feature on Europa's surface that some interpret as a region where the subsurface ocean has melted through the icy crust. This interpretation is extremely controversial. Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the surface.[34] The different models for the estimation of the ice shell thickness give values between a few hundred meters and tens of kilometers.[35]

The best evidence for the so-called "thick ice" model is a study of Europa's large craters. The largest craters are surrounded by concentric rings and appear to be filled with relatively flat, fresh ice; based on this and on the calculated amount of heat generated by Europan tides, it is predicted that the outer crust of solid ice is approximately 10–30 km (6–19 mi) thick, including a ductile "warm ice" layer, which could mean that the liquid ocean underneath may be about 100 km (60 mi) deep.[25] This leads to a volume of Europa's oceans of 3 × 1018 m3, slightly more than two times the volume of Earth's oceans.

The so-called "thin ice" model considers only those topmost layers of Europa's crust which behave elastically when affected by Jupiter's tides. One example is flexure analysis, in which the moon's crust is modeled as a plane or sphere weighted and flexed by a heavy load. Models such as this suggest the ice crust could be as thin as 200 metres (660 ft). The "thin ice" model allows regular contact of the liquid interior with the surface through open ridges.[35]

The Galileo orbiter found that Europa has a weak magnetic moment, which is induced by the varying part of the Jovian magnetic field. The field strength at the magnetic equator (about 120 nT) created by this magnetic moment is about one-sixth the strength of Ganymede's field and six times the value of Callisto's.[36] The existence of the induced moment requires a layer of a highly electrically conductive material in the moon's interior. A likely candidate for this role is a large subsurface ocean of liquid saltwater.[20] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the dark, reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within.[37] Sulfuric acid hydrate is another possible explanation for the contaminant observed spectroscopically.[38] In either case, since these materials are colorless or white when pure, some other material must also be present to account for the reddish color. Sulfur compounds are suspected.[39]

Atmosphere

Observations with the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph of the Hubble Space Telescope, first described in 1995, revealed that Europa has a tenuous atmosphere composed mostly of molecular oxygen (O2).[40][9] The surface pressure of Europa's atmosphere is 1 μPa, or 10−11 that of the Earth. At equivalent temperature and pressure to Earth's atmosphere at sea level, Europa's oxygen would "fill only about a dozen Houston Astrodomes".[9] In 1997, the Galileo spacecraft confirmed the presence of a tenuous ionosphere (an upper-atmospheric layer of charged particles) around Europa created by solar radiation and energetic particles from Jupiter's magnetosphere,[41][42] providing evidence of an atmosphere.

Unlike the oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, Europa's is not of biological origin. As first predicted by R. E. Johnson and colleagues,[43] the "surface-bounded atmosphere" forms through radiolysis, the dissociation of molecules through radiation. Solar ultraviolet radiation and charged particles (ions and electrons) from the Jovian magnetospheric environment collide with Europa's icy surface, splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen constituents. These chemical components are then adsorbed and "sputtered" into the atmosphere. The same radiation also creates collisional ejections of these products from the surface, and the balance of these two processes forms an atmosphere.[44] Molecular oxygen is the densest component of the atmosphere because it has a long lifetime; after returning to the surface, it does not stick (freeze) like a water or hydrogen peroxide molecule but rather desorbs from the surface and starts another ballistic arc. Molecular hydrogen never reaches the surface, as it is light enough to escape Europa's surface gravity.[45][46]

Observations of the surface have revealed that some of the molecular oxygen produced by radiolysis is not ejected from the surface. Since the surface may interact with the subsurface ocean (based on the geological discussion above), this molecular oxygen may make its way to the ocean, where it could aid in biological processes.[47]

The molecular hydrogen that escapes Europa's gravity, along with atomic and molecular oxygen, forms a torus (ring) of gas in the vicinity of Europa's orbit around Jupiter. This "neutral cloud" has been detected by both the Cassini and Galileo spacecraft, and has a greater content (number of atoms and molecules) than the neutral cloud surrounding Jupiter's inner moon Io. Models predict that almost every atom or molecule in Europa's torus is eventually ionized, thus providing a source to Jupiter's magnetospheric plasma. [48]

Possible extraterrestrial life

It has been suggested that life may exist in Europa's under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean hydrothermal vents or the Antarctic Lake Vostok.[49] Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to microbial life on Earth in the deep ocean.[50][51] So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa, but the likely presence of liquid water has spurred calls to send a probe there.[52]

Until the 1970s, life, at least as the concept is generally understood, was believed to be entirely dependent on energy from the Sun. Plants on Earth's surface capture energy from sunlight to photosynthesize sugars from carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen in the process, and are then eaten by oxygen-respiring animals, passing their energy up the food chain. Even life in the ocean depths, where sunlight cannot reach, was believed to obtain its nourishment either from consuming organic detritus rained down from the surface waters or from eating animals that did.[53] A world's ability to support life was thought to depend on its access to sunlight. However, in 1977, during an exploratory dive to the Galapagos Rift in the deep-sea exploration submersible Alvin, scientists discovered colonies of giant tube worms, clams, crustaceans, mussels, and other assorted creatures clustered around undersea volcanic features known as black smokers.[53] These creatures thrive despite having no access to sunlight, and it was soon discovered that they comprise an entirely independent food chain. Instead of plants, the basis for this food chain was a form of bacterium that derived its energy from oxidization of reactive chemicals, such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, that bubbled up from the Earth's interior. This chemosynthesis revolutionized the study of biology by revealing that life need not be sun-dependent; it only requires water and an energy gradient in order to exist. It opened up a new avenue in astrobiology by massively expanding the number of possible extraterrestrial habitats. Europa's unlit interior is now considered to be the most likely location for extant extraterrestrial life in the Solar System.[54]

While the tube worms and other multicellular eukaryotic organisms around these hydrothermal vents respire oxygen and thus are indirectly dependent on photosynthesis, anaerobic chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea that inhabit these ecosystems provide a possible model for life in Europa's ocean. The energy provided by tidal flexing drives active geological processes within Europa's interior, just as they do to a far more obvious degree on its sister moon Io. While Europa, like the Earth, may possess an internal energy source from radioactive decay, the energy generated by tidal flexing would be several orders of magnitude greater than any radiological source.[55] However, such an energy source could never support an ecosystem as large and diverse as the photosynthesis-based ecosystem on Earth's surface.[56] Life on Europa could exist clustered around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, or below the ocean floor, where endoliths are known to habitate on Earth. Alternatively, it could exist clinging to the lower surface of the moon's ice layer, much like algae and bacteria in Earth's polar regions, or float freely in Europa's ocean.[57] However, if Europa's ocean were too cold, biological processes similar to those known on Earth could not take place. Similarly, if it were too salty, only extreme halophiles could survive in its environment.[57]

In 2006, Robert Pappalardo, an assistant professor within the University of Colorado's space department, said,

"We’ve spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this … but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life … and not just four billion years ago … but today."[58]

Exploration

Most human knowledge of Europa has been derived from a series of flybys since the 1970s. The sister crafts Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 were the first to visit Jupiter, in 1973 and 1974, respectively; the first photos of Jupiter's largest moons produced by the Pioneers were fuzzy and dim.[21] The Voyager flybys followed in 1979, while the Galileo mission orbited Jupiter for eight years beginning in 1995 and provided the most detailed examination of the Galilean moons as of 2008[update].

Various proposals have been made for future missions. Any mission to Europa would need to be protected from the high radiation levels sustained by Jupiter.[13] The aims of these missions have ranged from examining Europa's chemical composition to searching for extraterrestrial life in its subsurface ocean.[50][59]

Spacecraft proposals and cancellations

Plans to send a probe to study Europa for signs of liquid water and possible life have been plagued by false starts and budget cuts.[60]

The plan for the extremely ambitious Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter was cancelled in 2005.[60][13].

Another possible mission, known as the Ice Clipper mission, would use an impactor similar to the Deep Impact mission—it would make a controlled crash into the surface of Europa, generating a plume of debris which would then be collected by a small spacecraft flying through the plume.[61] Without the need for an insertion and relaunch of the spacecraft(s) from an orbit around Jupiter or Europa, this would be one of the least expensive missions since the necessary amount of fuel would be decreased.[62]

More ambitious ideas have been put forward for a capable lander to test for evidence of life that might be frozen in the shallow subsurface, or even to directly explore the possible ocean beneath Europa's ice. One proposal calls for a large nuclear-powered "melt probe" (cryobot) which would melt through the ice until it hit the ocean below.[63] The Planetary Society says that drilling a hole below the surface would be a main goal.[13] Once it reached the water, it would deploy an autonomous underwater vehicle (hydrobot) which would gather information and send it back to Earth.[64] Both the cryobot and the hydrobot would have to undergo some form of extreme sterilization to prevent detection of Earth organisms instead of native life and to prevent contamination of the subsurface ocean.[65] This proposed mission has not yet reached a serious planning stage.[66]

Proposed for a launch in 2020, the Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) is a joint NASA/ESA proposal for exploration of Jupiter's moons. In February 2009 it was announced that ESA/NASA had given this mission priority ahead of the Titan Saturn System Mission[67]. ESA's contribution will still face funding competition from other ESA projects[68]. EJSM consists of the NASA-led Jupiter Europa Orbiter, the ESA-led Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter, and possibly a JAXA-led Jupiter Magnetospheric Orbiter. EJSM supersedes the Jovian Europa Orbiter study.

See also

- Colonization of Europa

- Jupiter's moons in fiction

- List of craters on Europa

- List of geological features on Europa

- List of lineae on Europa

- Moons of Jupiter

References

- ^ "JPL HORIZONS solar system data and ephemeris computation service". Solar System Dynamics. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ a b c d Calculated on the basis of other parameters

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Overview of Europa Facts". NASA. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ a b Using the mean radius

- ^ See Geissler et al. (1998) in orbit section for evidence of non-synchronous orbit.

- ^ Bills, Bruce G. (2005). "Free and forced obliquities of the Galilean satellites of Jupiter". Icarus. 175: 233–247. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.10.028.

- ^ a b Yeomans, Donald K. (2006-07-13). "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ a b Lucy-Ann McFadden, Paul Weissman, Torrence Johnson (2007). The Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Elsevier. p. 432.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Savage, Donald (1995-02-23). "Hubble Finds Oxygen Atmosphere on Europa". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mass of Europa: 48 Yg. Mass of Triton plus all smaller moons: 39.5 Yg (see note g here)

- ^ Tritt, Charles S. (2002). "Possibility of Life on Europa". Milwaukee School of Engineering. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ "Tidal Heating". geology.asu.edu. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ^ a b c d Friedman, Louis (2005-12-14). "Projects: Europa Mission Campaign; Campaign Update: 2007 Budget Proposal". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ David, Leondard (2006-02-07). "Europa Mission: Lost In NASA Budget". Space.com. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ "Satellites of Jupiter". The Galileo Project. Rice University. 1995. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ "Simon Marius". Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. University of Arizona. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Marius, S.; (1614) Mundus Iovialis anno M.DC.IX Detectus Ope Perspicilli Belgici [1], where he attributes the suggestion to Johannes Kepler

- ^ a b Marazzini, C. (2005). "The names of the satellites of Jupiter: from Galileo to Simon Marius". Lettere Italiana. 57 (3): 391–407.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cowen, Ron (2008-06-07). "A Shifty Moon". Science News.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Kivelson, M. G. (2000). "Galileo Magnetometer Measurements: A Stronger Case for a Subsurface Ocean at Europa". Science. 289 (5483): 1340–1343. doi:10.1126/science.289.5483.1340. PMID 10958778.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Europa: Another Water World?". Project Galileo: Moons and Rings of Jupiter. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Arnett, B.; Europa (November 7, 1996)

- ^ a b Hamilton, C. J. "Jupiter's Moon Europa".

- ^ "Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ a b Schenk, P. M.; Chapman, C. R.; Zahnle, K.; Moore, J. M.; Chapter 18: Ages and Interiors: the Cratering Record of the Galilean Satellites, in Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ^ "High Tide on Europa". Astrobiology Magazine. astrobio.net. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ^ P. E. Geissler, R. Greenberg; et al. (1998). "Evolution of Lineaments on Europa: Clues from Galileo Multispectral Imaging Observations". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Patricio H. Figueredo and Ronald Greeley (2003). "Resurfacing history of Europa from pole-to-pole geological mapping". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ T.A. Hurford, A.R. Sarid and R. Greenberg (2006). "Cycloidal cracks on Europa: Improved modeling and non-synchronous rotation implications". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Kattenhorn, Simon A. (2002). "Nonsynchronous Rotation Evidence and Fracture History in the Bright Plains Region, Europa". Icarus. 157: 490–506. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6825.

- ^ a b Christophe Sotin, James W. Head III and Gabriel Tobie (2001). "Europa: Tidal heating of upwelling thermal plumes and the origin of lenticulae and chaos melting" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Jason C. Goodman, Geoffrey C. Collins, John Marshall, Raymond T. Pierrehumbert. "Hydrothermal Plume Dynamics on Europa: Implications for Chaos Formation" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Greenberg, R.; Europa: The Ocean Moon: Search for an Alien Biosphere, Springer Praxis Books, 2005

- ^ Greeley, R. et al.; Chapter 15: Geology of Europa, in Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ^ a b Billings, S. E. (2005). "The great thickness debate: Ice shell thickness models for Europa and comparisons with estimates based on flexure at ridges". Icarus. 177 (2): 397–412. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.03.013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zimmer, C. (2000). "Subsurface Oceans on Europa and Callisto: Constraints from Galileo Magnetometer Observations" (PDF). Icarus. 147: 329–347. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6456.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ T. B. McCord, G. B. Hansen; et al. (1998). "Salts on Europa's Surface Detected by Galileo's Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ R.W. Carlson, M.S. Anderson (2005). "Distribution of hydrate on Europa: Further evidence for sulfuric acid hydrate". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Calvin, Wendy M. (1995). "Spectra of the ice Galilean satellites from 0.2 to 5 µm: A compilation, new observations, and a recent summary". J.of Geophys. Res. 100: 19, 041–19, 048. doi:10.1029/94JE03349.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hall, D. T. et al.; Detection of an oxygen atmosphere on Jupiter's moon Europa, Nature, Vol. 373 (23 February 1995), 677–679 (accessed 15 April 2006)

- ^ Kliore, A. J. (1997). "The Ionosphere of Europa from Galileo Radio Occultations". Science. 277 (5324): 355–358. doi:10.1126/science.277.5324.355. PMID 9219689. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Galileo Spacecraft Finds Europa has Atmosphere". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 1997. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson, R. E.; Lanzerotti, L. J.; Brown, W. L. (1982). "Planetary applications of ion induced erosion of condensed-gas frosts". Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shematovich, V. I. (2003). "Surface-bounded oxygen atmosphere of Europa". EGS - AGU - EUG Joint Assembly (Abstracts from the meeting held in Nice, France). Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Liang, M. C. (2005). "Atmosphere of Callisto" (PDF). Journal of Geophysics Research. 110: E02003. doi:10.1029/2004JE002322.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Smyth, W.H. (August 15, 2007). "Processes Shaping Galilean Satellite Atmospheres from the Surface to the Magnetosphere" (pdf). Abstracts. Workshop on Ices, Oceans, and Fire: Satellites of the Outer Solar System, Boulder, Colorado. pp. 131–132.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chyba and Hand, "Life without photosynthesis" [2]

- ^ Smyth, W. H. (2006). "Europa's atmosphere, gas tori, and magnetospheric implications". Icarus. 181: 510. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.10.019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Exotic Microbes Discovered near Lake Vostok, Science@NASA (December 10, 1999)

- ^ a b Chandler, D. L. (2002-10-20). "Thin ice opens lead for life on Europa". NewScientist.com.

- ^ Jones, N.; Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow, NewScientist.com (11 December 2001)

- ^ Phillips, C.; Time for Europa, Space.com (28 September 2006)

- ^ a b Sean Chamberlin (1999). "Creatures Of The Abyss: Black Smokers and Giant Worms". Fullerton College. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Louis N. Irwin (2001). "Alternative Energy Sources Could Support Life on Europa" (PDF). Departments of Geological and Biological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Wilson, Colin P. (2007). "Tidal Heating on Io and Europa and its Implications for Planetary Geophysics". Geology and Geography Dept, Vassar College. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ McCollom, T. M. (1999). "Methanogenesis as a potential source of chemical energy for primary biomass production by autotrophic organisms in hydrothermal systems on Europa". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ a b Giles M. Marion, Christian H. Fritsen, Hajo Eicken, Meredith C. Payne (2003). "The Search for Life on Europa: Limiting Environmental Factors, Potential Habitats, and Earth Analogues". Astrobiology. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ David, L.; Europa Mission: Lost In NASA Budget, Space.com (7 February 2006)

- ^ Muir, H.; Europa has raw materials for life, NewScientist.com (22 May 2002)

- ^ a b Berger, B.; NASA 2006 Budget Presented: Hubble, Nuclear Initiative Suffer Space.com (7 February 2005)

- ^ Goodman, J.; Re: Galileo at Europa, MadSci Network forums, September 9, 1998

- ^ McKay C. P. (2002). "Planetary protection for a Europa surface sample return: The ice clipper mission". Advances in Space Research. 30 (6): 1601–1605. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(02)00480-5.

- ^ Knight, W.; Ice-melting robot passes Arctic test, NewScientist.com (14 January 2002)

- ^ Bridges, A.; Latest Galileo Data Further Suggest Europa Has Liquid Ocean, Space.com (10 January 2000)

- ^ National Academy of Sciences Space Studies Board, Preventing the Forward Contamination of Europa, National Academy Press, Washington (DC), June 29, 2000

- ^ Powell, J. (2005). "NEMO: A mission to search for and return to Earth possible life forms on Europa". Acta Astronautica. 57 (2–8): 579–593. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2005.04.003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7897585.stm

- ^ http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=41177

Further reading

- Greenberg, Richard (2008). Unmasking Europa: The Search for Life on Jupiter's Ocean Moon. Springer. ISBN 0387479368.

- Greenberg, Richard (2005). Europa - The Ocean Moon: Search For An Alien Biosphere. Springer. ISBN 3540224505.

- Bagenal, Fran (2004). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521818087.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rothery, David A. (1999). Satellites of the Outer Planets: Worlds in Their Own Right. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 019512555X.

- Harland, David M. (2000). Jupiter Odyssey: The Story of NASA's Galileo Mission. Springer. ISBN 1852333014.

External links

- Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery at NASA/JPL

- Europa Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- The Calendars of Jupiter

- Are our nearest living neighbours on one of Jupiter's Moons?