Fake news

Fake news is a type of hoax or deliberate spread of misinformation, be it via the traditional news media or via social media, with the intent to mislead in order to gain financially or politically.[1] It often employs eye-catching headlines or entirely fabricated news-stories in order to increase readership and, in the case of internet-based stories, online sharing.[1] In the latter case, profit is made in a similar fashion to clickbait and relies on ad-revenue generated regardless of the veracity of the published stories.[1] Easy access to ad-revenue, increased political polarization and the ubiquity of social media, primarily the Facebook newsfeed have been implicated in the spread of fake news.[2][1] Anonymously-hosted fake news websites lacking known publishers have also been implicated, because they make it difficult to prosecute sources of fake news for libel or slander.[3]

Definition

This section needs expansion with: definition. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (March 2017) |

Fake news is a neologism used to refer to non-satirical news stories, which have originated online (on social media or fake news websites) or in the traditional news media, have no basis in fact, but are presented as and believed to be factually accurate.[4] The intention and purpose behind fake news is important. What appears to be fake news may in fact be news satire, which uses exaggeration and introduces non-factual elements, and is intended to amuse or make a point, rather than to deceive. Fake news may actually be convincing fiction, such as the radio dramatisation of H.G. Wells' novel The War of the Worlds, broadcast in 1938; or it may be one of the variety of possible hoaxes. Propaganda can also be fake news.[1]

In the context of the United States and its election processes in the twenty-first century, fake news generated considerable controversy and argument, with some commentators defining concern over it as moral panic or mass hysteria and others deeply worried about damage done to public trust.[5][6][7][8] In January 2017 the United Kingdom House of Commons conducted a Parliamentary inquiry into the "growing phenomenon of fake news".[9]

Identifying

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) published a summary in diagram form (pictured at right) to assist people to recognize fake news.[10] Its main points are:

- Consider the source (to understand its mission and purpose)

- Read beyond the headline (to understand the whole story)

- Check the authors (to see if they are real and credible)

- Assess the supporting sources (to ensure they support the claims)

- Check the date of publication (to see if the story is relevant and up to date)

- Ask if it is a joke (to determine if it is meant to be satire)

- Review your own biases (to see if they are affecting your judgement)

- Ask experts (to get confirmation from independent people with knowledge).

The independent, not-for-profit media journal The Conversation created a very short animated explanation of its fact checking process, explaining that it involves "extra checks and balances, including blind peer review by a second academic expert, additional scrutiny and editorial oversight".[11]

Historical examples

Ancient and medieval

Significant fake news stories can be traced back to Octavian's 1st century campaign of misinformation against Mark Antony[12] and the forged 8th century Donation of Constantine, which supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope.[13]

Seventeenth century

After the invention of the printing press in 1439, publications became widespread but there was no standard of journalistic ethics to follow. By the 17th century, historians began the practice of citing their sources in footnotes. In 1610 when Galileo went on trial, the demand for verifiable news increased.[12]

Eighteenth century

During the eighteenth century publishers of fake news were fined and banned in the Netherlands; one man, Gerard Lodewijk van der Macht, was banned four times by Dutch authorities—and four times he moved and restarted his press.[14]

Benjamin Franklin wrote fake news about murderous "scalping" Indians working with King George III, in an effort to influence public opinion for the American Revolution.[12]

The canard succeeded the 16th century pasquinade. Canards were sold in Paris on the street for two centuries. In 1793, Marie Antoinette was executed in part because of popular hatred engendered by a canard on which her face had been printed.[15]

Nineteenth century

One of the earliest instances of fake news was the Great Moon Hoax of 1835. The New York Sun published articles about a real-life astronomer and a made-up colleague who, according to the hoax, had observed bizarre life on the moon. The fictionalized articles successfully attracted new subscribers, and the penny paper suffered very little backlash after it admitted the series had been a hoax the next month.[16][12] Such stories were intended to entertain readers, and not to mislead them.[14]

In the late 1800s, Joseph Pulitzer and other yellow journalism publishers goaded the United States into the Spanish–American War, which was precipitated when the U.S.S. Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba.[17]

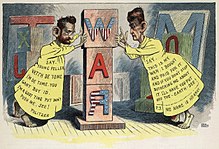

Twentieth century

Fake news is similar to the concept of yellow journalism and political propaganda, frequently employing the same strategies used by early 20th century penny presses.[18][19][20]

During the First World War, one of the most notorious forms of anti-German atrocity propaganda was that of an alleged "German Corpse Factory" in which the German battlefield dead were rendered down for fats used to make nitroglycerine, candles, lubricants, human soap, and boot dubbing. Unfounded rumors regarding such a factory circulated in the Allied press since 1915, and by 1917 the English-language publication North China Daily News published these allegations as true at a time when Britain was trying to convince China to join the Allied war effort; this was based on new, allegedly true stories from The Times and The Daily Mail which turned out to be forgeries. These false allegations became known as such after the war, and in the Second World War Joseph Goebbels used the story in order to deny the ongoing massacre of Jews as British propaganda. According to Joachim Neander and Randal Marlin, the story also "encouraged later disbelief" when reports about the Holocaust surfaced after the liberation of Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps.[21]

After Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power in Germany in 1933, they established the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under the control of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.[22] The Nazis used both print and broadcast journalism to promote their agendas, either by obtaining ownership of those media or exerting political influence.[23] Throughout World War II, both the Axis and the Allies employed fake news in the form of propaganda to persuade publics at home and in enemy countries.[24][25] The British Political Warfare Executive used radio broadcasts and distributed leaflets to discourage German troops.[22]

Twenty-first century

In the 21st century, the use and impact of fake news became widespread, as well as the usage of the term. Besides being used to refer to made-up stories designed to deceive readers to maximize traffic and profit, the term was also used to refer to satirical news, whose purpose is not to mislead but rather to inform viewers and share humorous commentary about real news and the mainstream media.[26][27] American examples of satire (as opposed to fake news) include the television show Saturday Night Live's Weekend Update, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report and The Onion newspaper.[28][29][30]

Fake news has become increasingly commercially motivated in the twenty-first century. In an interview with NPR, Jestin Coler, former CEO of the fake media conglomerate Disinfomedia, revealed who writes fake news articles, who funds these articles, and why fake news creators create and distribute false information.[31] Coler, who has since left his role as a fake news creator, shared that his company employed anywhere from 20 to 25 writers at a time and made $10,000 to $30,000 monthly from advertisements.[31] Coler began his career in journalism as a magazine salesman before working as a freelance writer, but launched into the fake news industry to prove to himself and others just how rapidly fake news can spread.[31] Disinfomedia is not the only outlet responsible for the distribution of fake news; Facebook users play a major role in feeding into fake news stories by making sensationalized stories "trend", according to BuzzFeed media editor Craig Silverman, and the individuals behind Google AdSense basically fund fake news websites and their content.[32] Many online fake news stories are being sourced out of a small city in Macedonia by teenagers being paid to pump out at a fast pace sensationalist stories, where approximately seven different fake news organizations are employing hundreds of teenagers to plagiarize stories for different U.S. based companies and parties.[33]

Kim LaCapria of the factchecking website Snopes has argued that, in America, fake news is a bipartisan phenomenon, saying that "[t]here has always been a sincerely held yet erroneous belief misinformation is more red than blue in America, and that has never been true."[35]

Global Prominence as a Result of 2016 US Elections

Fake News became a global subject and was widely introduced to billions as a subject mainly due to the 2016 US Presidential Elections. Numerous political commentators and journalists wrote and stated in media that 2016 was the year of Fake News and as a result nothing will ever be the same in politics and cyber security. Many governmental bodies in USA and Europe started looking at contingencies and regulations to combat Fake News specially when as part of a coordinated intelligence campaign by hostile foreign governments. Many online tech giants like Facebook and Google also started putting in place means to combat Fake News in 2016 as a result of the phenomena becoming globally known, specially as a result of its use in the 2016 US Presidential and Capitol Hill Elections.

Fake News in Mainstream Media

On November 2, 2016, six days before the election, Fox News anchor Bret Baier led off his news show with a report that multiple FBI sources told him that it was 99% likely that Hillary Clinton's email server had been hacked by “five foreign intelligence agencies.” The next day, Baier reported there would "likely be an indictment" in the investigation of Hillary Clinton's role in the Clinton Foundation and State Department. [36] One day later, on November 4, Baier retracted and apologized for both stories, now saying there was no evidence at this time for either allegation. [37] No explanation was given as to how his originally-claimed multiple informants had all given him the same unverified story.

Fake News and Social Media

In the United States in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, fake news was particularly prevalent and spread rapidly over social media "bots", according to researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute.[38] [39] The impact of fake news on public opinion remains an open question, and a working paper by researchers at Stanford University and New York University concluded that fake news had "little to no effect" on its outcome, noting that only 8% of voters read a fake news story, and that recall of the stories was low.[40][41] Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel became a target for fake news in the run-up to the 2017 German federal election.[42]

In the early weeks of his presidency, U.S. President Donald Trump frequently used the term "fake news" to refer to traditional news media, singling out CNN.[43] Linguist George Lakoff says this creates confusion about the phrase's meaning.[44]

After Republican Colorado State Senator Ray Scott used the term as a reference to a column in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, the newspaper's publisher threatened a defamation lawsuit.[45][46]

Fake News Websites and Impact

The impact of fake news is a worldwide phenomenon.[47] Fake news is often spread through the use of fake news websites, which, in order to gain credibility, specialize in creating attention-grabbing news, often impersonating well-known news sources.[48][49][50] In 2017, the inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee claimed that Fake News was one of the three most significant new disturbing Internet trends that must first be resolved, if the Internet is to be capable of truly "serving humanity." The other two new disturbing trends which Berners-Lee described as threatening the Internet were the recent surge in the use of the Internet by governments for both citizen-surveillance purposes, and for cyber-warfare purposes.[51]

Users and Organized Bots on Social Media

In the 21st century, the capacity to mislead was enhanced by the widespread use of social media. For example, one 21st century website that enabled fake news' proliferation was the Facebook newsfeed.[52][53] In late 2016 fake news gained notoriety following the uptick in news content by this means,[54][2] and its prevalence on the micro-blogging site Twitter.[54]

In the United States, a large portion of Americans use Facebook or Twitter to receive news.[55] This, in combination with increased political polarization and filter bubbles, led to a tendency for readers to mainly read headlines.[56] Fake news was implicated in influencing the 2016 American presidential election.[57] Fake news saw higher sharing on Facebook than legitimate news stories,[58][59][60] which analysts explained was because fake news often panders to expectations or is otherwise more exciting than legitimate news.[59][20] Facebook itself initially denied this characterization.[61][53] A Pew Research poll conducted in December 2016 found that 64% of U.S. adults believed completely made-up news had caused "a great deal of confusion" about the basic facts of current events, while 24% claimed it had caused "some confusion" and 11% said it had caused "not much or no confusion".[62] Additionally, 23% of those polled admitted they had personally shared fake news, whether knowingly or not.

Research from Northwestern University concluded that 30% of all fake news traffic, as opposed to only 8% of real news traffic, could be linked back to Facebook.[63] Fake news consumers, they concluded, do not exist in a filter bubble; many of them also consume real news from established news sources.[63] The fake news audience is only 10 percent of the real news audience, and most fake news consumers spent a relatively similar amount of time on fake news compared with real news consumers—with the exception of Drudge Report readers, who spent more than 11 times longer reading the website than other users.[63]

In China, fake news items have occasionally spread from such sites to more well-established news-sites resulting in scandals including "Pizzagate".[64] In the wake of western events, China's Ren Xianling of the Cyberspace Administration of China suggested a "reward and punish" system be implemented to avoid fake news.[65]

Response

During the 2016 United States presidential election, the fabrication and coverage of fake news increased substantially.[66] This resulted in a widespread response to combat the spread of fake news.[67][68][69] The volume and reluctance of fake news websites to respond to fact-checking organizations has posed a problem to inhibiting the spread of fake news through fact checking alone.[70] In an effort to reduce the effects of fake news, fact-checking websites, including Snopes.com and FactCheck.org, have posted guides to spotting and avoiding fake news websites.[67][71] Social media sites and search engines, such as Facebook and Google, received criticism for facilitating the spread of fake news.[69] Both of these corporations have taken measures to explicitly prevent the spread of fake news; critics, however, believe more action is needed.[69] After the 2016 American election and the run-up to the German election, Facebook began labeling and warning of inaccurate news[72][73][74] and partnered with independent fact-checkers to label inaccurate news, warning readers before sharing it.[72][73][74] Artificial intelligence is one of the more recent technologies being developed in the United States and Europe to recognize and eliminate fake news through algorithms.[68]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Hunt, Elle (December 17, 2016). "What is fake news? How to spot it and what you can do to stop it". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Woolf, Nicky (November 11, 2016). "How to solve Facebook's fake news problem: experts pitch their ideas". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Callan, Paul. "Sue over fake news? Not so fast". CNN. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Allcott, Hunt; Gentzkow, Matthew (January 2017). "Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election" (PDF). Stanford University, New York University, National Bureau of Economic Research: 5–6. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

We define 'fake news' as news stories that have no factual basis but are presented as facts. By 'news stories,' we mean stories that originated in social media or the news media ... By 'presented as facts,' we exclude websites that are well-known to be satire, such as the Onion.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shafer, Jack (November 22, 2016). "The Cure for Fake News Is Worse Than the Disease". Politico. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Gobry, Pascal-Emmanuel (December 12, 2016). "The crushing anxiety behind the media's fake news hysteria". The Week. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn. "Russia Hysteria Infects WashPost Again: False Story About Hacking US Electrical Grid". The Intercept. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Morrissey, Edward. "The Snarling Contempt of the Media's Fake News Hysteria". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Fake news inquiry by MPs examines threat to democracy". BBC News. January 30, 2017.

- ^ "How to Spot Fake News". IFLA blogs. January 27, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Creagh, Sunanda; Mountain, Wes (February 17, 2017). "How we do Fact Checks at The Conversation". The Conversation. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The Long and Brutal History of Fake News". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Before Jon Stewart". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Borel, Brooke (January 4, 2017). "Fact-Checking Won't Save Us From Fake News". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Darnton, Robert (February 13, 2017). "The True History of Fake News". New York Review of Books. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Great Moon Hoax". HISTORY.com. August 25, 1835. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Milestones: 1866–1898". history.state.gov. Office of the Historian. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "To Fix Fake News, Look To Yellow Journalism". JSTOR Daily. November 29, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Russian propaganda effort helped spread 'fake news' during election, experts say". Washington Post. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Agrawal, Nina. "Where fake news came from — and why some readers believe it". latimes.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "The corpse factory and the birth of fake news". BBC News. February 17, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b "American Experience . The Man Behind Hitler . | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Press in the Third Reich".

- ^ Wortman, Marc (January 29, 2017). "The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Inside America's Shocking WWII Propaganda Machine". December 19, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ JEREMY W. PETERS (December 25, 2016). "Wielding Claims of 'Fake News,' Conservatives Take Aim at Mainstream Media". The New York Times.

- ^ "A look at "Daily Show" host Jon Stewart's legacy".

- ^ "Why SNL's 'Weekend Update' Change Is Brilliant". Esquire. September 12, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Area Man Realizes He's Been Reading Fake News For 25 Years". NPR.org. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "'The Daily Show (The Book)' is a reminder of when fake news was funny". newsobserver. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sydell, Laura (November 23, 2016). "We Tracked Down A Fake-News Creator In The Suburbs. Here's What We Learned". NPR.

- ^ Davies, Dave (December 14, 2016). "Fake News Expert On How False Stories Spread And Why People Believe Them". NPR.

- ^ Kirby, Emma Jane (December 5, 2016). "The city getting rich from fake news". BBC.

- ^ Grynbaum, Michael (February 17, 2017). "Trump Calls the News Media the 'Enemy of the American People'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Tait, Amelia. Fake news is a problem for the left, too. New Statesman. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "BREAKING: FBI Sources Believe Clinton Foundation Scandal Headed Towards Indictment". Fox News. November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Fox News apologizes for falsely reporting that Clinton faces indictment". Washington Post. November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ John Markoff (November 17, 2016). "Automated Pro-Trump Bots Overwhelmed Pro-Clinton Messages, Researchers Say". The New York Times.

- ^ Gideon Resnick (November 17, 2016). "How Pro-Trump Twitter Bots Spread Fake News". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Christopher Ingraham (January 24, 2017). "Real research suggests we should stop freaking out over fake news". The Washington Post.

- ^ Crawford, Krysten. "Stanford study examines fake news and the 2016 presidential election". Stanford News. Stanford University. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ "Angela Merkel replaces Hillary Clinton as prime target of fake news, analysis finds". Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "'Very Fake News': Pres. Trump Questioned on Intel Leaks by CNN's Acosta". February 16, 2017.

- ^ "With 'Fake News,' Trump Moves From Alternative Facts To Alternative Language". NPR.org. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Post, The Washington. "Grand Junction Daily Sentinel standing up to state lawmaker's charges of "fake news" – The Denver Post". Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "When A Politician Says 'Fake News' And A Newspaper Threatens To Sue Back". NPR.org. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Connolly, Kate; Chrisafis, Angelique; McPherson, Poppy; Kirchgaessner, Stephanie; Haas, Benjamin; Phillips, Dominic; Hunt, Elle; Safi, Michael (December 2, 2016). "Fake news: an insidious trend that's fast becoming a global problem". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Chen, Adrian (June 2, 2015). "The Agency". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ LaCapria, Kim (November 2, 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors - Snopes.com's updated guide to the internet's clickbaiting, news-faking, social media exploiting dark side.", Snopes.com, retrieved November 19, 2016

- ^ Ben Gilbert (November 15, 2016), "Fed up with fake news, Facebook users are solving the problem with a simple list", Business Insider, retrieved November 16, 2016,

Some of these sites are intended to look like real publications (there are false versions of major outlets like ABC and MSNBC) but share only fake news; others are straight-up propaganda created by foreign nations (Russia and Macedonia, among others).

- ^ The World Wide Web's inventor warns it's in peril on 28th anniversary By Jon Swartz, USA Today. March 11, 2017. Downloaded Mar. 11, 2017.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (December 12, 2016). "Facebook, in Cross Hairs After Election, Is Said to Question Its Influence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Matthew Garrahan and Tim Bradshaw, Richard Waters, (November 21, 2016). "Harsh truths about fake news for Facebook, Google and Twitter". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "The Long and Brutal History of Fake News". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Gottfried, Jeffrey; Shearer, Elisa (May 26, 2016). "News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Solon, Olivia (November 10, 2016). "Facebook's failure: did fake news and polarized politics get Trump elected?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Forget Facebook and Google, burst your own filter bubble". Digital Trends. December 6, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "This Analysis Shows How Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News On Facebook". BuzzFeed. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "Just how partisan is Facebook's fake news? We tested it". PCWorld. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Fake news is dominating Facebook". 6abc Philadelphia. November 23, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (November 12, 2016). "Facebook, in Cross Hairs After Election, Is Said to Question Its Influence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Barthel, Michael; Mitchell, Amy; Holcomb, Jesse (December 15, 2016). "Many Americans Believe Fake News Is Sowing Confusion". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Is 'fake news' a fake problem?". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Evidence ridiculously thin for Clinton sex network claim". @politifact. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "China says terrorism, fake news impel greater global internet curbs". Reuters. November 20, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Holan, Angie Drobnic (December 13, 2016). "2016 Lie of the Year: Fake news". PolitiFact.

- ^ a b LaCapria, Kim (March 2, 2017). "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors". Snopes.com.

- ^ a b Marr, Bernard (March 1, 2017). "Fake News: How Big Data And AI Can Help". Forbes.

- ^ a b c Wakabayashi, Isaac (January 25, 2017). "In Race Against Fake News, Google and Facebook Stroll to the Starting Line". The New York Times.

- ^ Gillin, Joshua (January 27, 2017). "Fact-checking fake news reveals how hard it is to kill pervasive 'nasty weed' online". PolitiFact.com.

- ^ Kiely, Eugene; Robertson, Lori (November 18, 2016). "How To Spot Fake News". FactCheck.org.

- ^ a b Stelter, Brian (January 15, 2017). "Facebook to begin warning users of fake news before German election". CNNMoney. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Clamping down on viral fake news, Facebook partners with sites like Snopes and adds new user reporting". Nieman Lab. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Kuchler, Hannah (January 15, 2017). "Facebook rolls out fake-news filtering service to Germany". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2017.