German reunification

The German reunification (Template:Lang-de) was the process in 1990 in which the German Democratic Republic (GDR/East Germany) joined the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG/West Germany) to form the reunited nation of Germany, and when Berlin reunited into a single city, as provided by its then Grundgesetz constitution Article 23. The end of the unification process is officially referred to as German unity (Template:Lang-de), celebrated on 3 October (German Unity Day) (Template:Lang-de).[1]

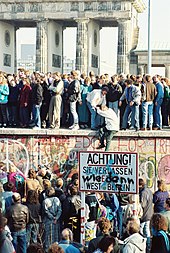

The East German regime started to falter in May 1989, when the removal of Hungary's border fence opened a hole in the Iron Curtain. It caused an exodus of thousands of East Germans fleeing to West Germany and Austria via Hungary. The Peaceful Revolution, a series of protests by East Germans, led to the GDR's first free elections on 18 March 1990, and to the negotiations between the GDR and FRG that culminated in a Unification Treaty.[1] Other negotiations between the GDR and FRG and the four occupying powers produced the so-called "Two Plus Four Treaty" (Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany) granting full sovereignty to a unified German state, whose two parts had previously still been bound by a number of limitations stemming from their post-World War II status as occupied regions.

The united Germany is considered to be the enlarged continuation of the Federal Republic and not a successor state. As such, it retained all of West Germany's memberships in international organizations including the European Community (later the European Union) and NATO, while relinquishing membership in the Warsaw Pact and other international organizations to which only East Germany belonged.

Naming

For political and diplomatic reasons, West German politicians carefully avoided the term "reunification" during the run-up to what Germans frequently refer to as die Wende. The official[1] and most common term in German is "Deutsche Einheit" ("German unity"); this is the term that Hans-Dietrich Genscher used in front of international journalists to correct them when they asked him about "reunification" in 1990.

After 1990, the term "die Wende" became more common. The term generally refers to the events (mostly in Eastern Europe) that led up to the actual reunification; in its usual context, this term loosely translates to "the turning point", without any further meaning. When referring to the events surrounding unification, however, it carries the cultural connotation of the time and the events in the GDR that brought about this "turnaround" in German history. However, civil rights activists from Eastern Germany rejected the term Wende as it was introduced by SED's (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, Socialist Unity Party of Germany) Secretary General Egon Krenz.[2]

Precursors to reunification

In 1945, the Third Reich ended in defeat and Germany was divided into two separate areas, with the east controlled as part of the Communist Soviet Bloc and the west aligned to Capitalist Europe (which formed into the European Community), including a division in military alliance that formed into the Warsaw Pact and NATO, respectively. The capital city of Berlin was divided into four occupied sectors of control, under the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom and France. Germans lived under such imposed divisions throughout the ensuing Cold War.

Into the 1980s, the Soviet Union experienced a period of economic and political stagnation, and they correspondingly decreased intervention in Eastern Bloc politics. In 1987, US President Ronald Reagan gave a speech at Brandenburg Gate challenging Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to "tear down this wall" that had separated Berlin. The wall had stood as an icon for the political and economic division between East and West, a division that Churchill had referred to as the "Iron Curtain". In early 1989, under a new era of Soviet policies of glasnost (openness), perestroika (economic restructuring) and taken to even more progressive levels by Gorbachev, the Solidarity movement took hold in Poland. Further inspired by other images of brave defiance, a wave of revolutions swept throughout the Eastern Bloc that year. In May 1989, Hungary removed their border fence and thousands of East Germans escaped to the West. The turning point in Germany, called "Die Wende", was marked by the "Peaceful Revolution" leading to the removal of the Berlin Wall with East and West Germany subsequently entering into negotiations toward eliminating the division that had been imposed upon Germans more than four decades earlier.

Process of reunification

Cooperation

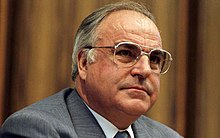

On 28 November 1989—two weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall—West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl announced a 10-point program calling for the two Germanies to expand their cooperation with the view toward eventual reunification.[3]

Initially, no timetable was proposed. However, events rapidly came to a head in early 1990. First, in March, the Party of Democratic Socialism—the former Socialist Unity Party of Germany—was heavily defeated in East Germany's first free elections. A grand coalition was formed under Lothar de Maizière, leader of the East German wing of Kohl's Christian Democratic Union, on a platform of speedy reunification. Second, East Germany's economy and infrastructure underwent a swift and near-total collapse. While East Germany had long been reckoned as having the most robust economy in the Soviet bloc, the removal of Communist hegemony revealed the ramshackle foundations of that system. The East German mark had been practically worthless outside of East Germany for some time before the events of 1989–90 further magnified the problem.

Economic merger

Discussions immediately began for an emergency merger of the German economies. On 18 May 1990, the two German states signed a treaty agreeing on monetary, economic and social union. This treaty is called Vertrag über die Schaffung einer Währungs-, Wirtschafts- und Sozialunion zwischen der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland ("Treaty Establishing a Monetary, Economic and Social Union between the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany")[4] in German and came into force on 1 July 1990, with the Deutsche Mark replacing the East German mark as the official currency of East Germany. The Deutsche Mark had a very high reputation among the East Germans and was considered stable.[5] While the GDR transferred its financial policy sovereignty to West Germany, the West started granting subsidies for the GDR budget and social security system.[6] At the same time many West German laws came into force in the GDR. This created a suitable framework for a political union by diminishing the huge gap between the two existing political, social, and economic systems.[6]

German Reunification Treaty

The Volkskammer, the Parliament of East Germany, passed a resolution on 23 August 1990 seeking the accession (Beitritt) of the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic of Germany, and the extension of the field of application of the Federal Republic's Basic Law to the territory of East Germany as allowed by article 23 of the West German Basic Law, effective 3 October 1990.[7][8][9] The East German Declaration of Accession (Beitrittserklärung) to the Federal Republic as allowed by article 23 of the West German Basic Law, approved by the Volkskammer on 23 August, was formally presented by its President to the President of the West German Bundestag by means of a letter dated 25 August 1990.[10] Thus, formally, the procedure of reunification by means of the accession of East Germany to West Germany, and of East Germany's acceptance of the Basic Law already in force in West Germany, was initiated as the unilateral, sovereign decision of East Germany, as allowed by the then existing provision of article 23 of the West German Basic Law.

In the wake of that resolution of accession, the "German reunification treaty",[11][12][13] commonly known in German as "Einigungsvertrag" (Unification Treaty) or "Wiedervereinigungsvertrag" (Reunification Treaty), that had been negotiated between the two German states since 2 July 1990, was signed by representatives of the two Governments on 31 August 1990. This Treaty, officially titled Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands (Treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic on the Establishment of German Unity), was approved by large majorities in the legislative chambers of both countries on 20 September 1990[14] (442–47 in the West German Bundestag and 299–80 in the East German Volkskammer). The amendments to the Federal Republic's Basic Law that were foreseen in the Unification Treaty or necessary for its implementation were adopted by the Federal Statute of 23 September 1990. In the German Democratic Republic, the constitutional law (Verfassungsgesetz) giving effect to the Treaty was published on 28 September 1990.[15] Under article 45 of the Treaty,[16] it entered into force according to international law on 29 September 1990, upon the exchange of notices regarding the completion of the respective internal constitutional requirements for the adoption of the treaty in both East Germany and West Germany.

With that last step, and in accordance with article 1 of the Treaty, and also in conformity with East Germany's Declaration of Accession presented to the Federal Republic, Germany was officially reunited at 00:00 CEST on 3 October 1990. East Germany joined the Federal Republic as the five Länder (states) of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. These states had been the five original states of East Germany, but had been abolished in 1952 in favour of a centralised system. As part of the 18 May treaty, the five East German states had been reconstituted on 23 August. At the same time, East and West Berlin reunited into one city, which became a city-state along the lines of the existing city-states of Bremen and Hamburg. In an emotional ceremony, at the stroke of midnight on 3 October 1990, the black-red-gold flag of West Germany—now the flag of a reunited Germany—was raised above the Brandenburg Gate marking the moment of German reunification.

Constitutional merger

The process chosen was one of two options implemented in the West German constitution (Basic Law) of 1949 to facilitate eventual reunification. The Basic Law stated that it was only intended for temporary use until a permanent constitution could be adopted by the German people as a whole. Via that document's (then-existing) Article 23, any new prospective Länder could adhere to the Basic Law by a simple majority vote. The initial eleven joining states of 1949 constituted the Trizone. West Berlin had been proposed as the 12th state, but was legally inhibited by Allied objections since Berlin as a whole was legally a quadripartite occupied area. Despite this, West Berlin's political affiliation was with West Germany, and in many fields it functioned de facto as if it were a component state of West Germany. In 1957 the Saar Protectorate joined West Germany under the Article 23 procedure as Saarland.

The other option was Article 146, which provided a mechanism for a permanent constitution for a reunified Germany. This route would have entailed a formal union between two German states that then would have had to, amongst other things, create a new constitution for the newly established country. However, by the spring of 1990 it was apparent that drafting a new constitution would require protracted negotiations that would open up numerous issues in West Germany. Even without this to consider, by the start of 1990 East Germany was in a state of utter collapse. In contrast, reunification under Article 23 could be implemented in as little as six months.

Ultimately, when the treaty on monetary, economic and social union was signed, it was decided to use the quicker process of Article 23. By this process, East Germany voted to dissolve itself and to join West Germany as five new states, and the area in which the Basic Law was in force simply extended to include them.[17] Thus, legally it was the five states, not East Germany as a whole, who acceded to the Federal Republic. The five new states held their first elections on 14 October.

The reunification was not a merger that created a third state out of the two. Rather, West Germany effectively absorbed East Germany. Accordingly, on Unification Day, 3 October 1990, the German Democratic Republic ceased to exist, and five new Federal States on its former territory joined the Federal Republic of Germany. East and West Berlin were reunited, and joined the Federal Republic as a full-fledged Federal City-State. Under this model, the Federal Republic of Germany, now enlarged to include the five states of the former German Democratic Republic plus the reunified Berlin, continued legally to exist under the same legal personality that was founded in May 1949.

While the Basic Law was modified rather than replaced by a constitution as such, it still permits the adoption of a formal constitution by the German people at some time in the future.

International effects

The practical result of that model is that the now expanded Federal Republic of Germany inherited the old West Germany's seats at the UN, NATO, the European Communities and other international organizations. It also continued to be a party to all the treaties the old West Germany signed prior to the moment of reunification. The same Basic Law and the same laws that were in force in the Federal Republic continued automatically in force, but now applied to the expanded territory. Also, the same President, Chancellor (Prime Minister) and Government of the Federal Republic remained in office, but their jurisdiction now included the newly acquired territory of the former East Germany.

To facilitate this process and to reassure other countries, some changes were made to the "Basic Law" (constitution). Article 146 was amended so that Article 23 of the current constitution could be used for reunification. After the five "New Länder" of East Germany had joined, the constitution was amended again to indicate that all parts of Germany are now unified. Article 23 was rewritten and it can still be understood as an invitation to others (e.g. Austria) to join, although the main idea of the change was to calm fears in (for example) Poland, that Germany would later try to rejoin with former eastern territories of Germany that were now Polish or parts of other countries in the East. The changes effectively formalised the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's permanent eastern border. These amendments to the Basic Law were mandated by Article I, section 4 of the Two Plus Four Treaty.[18]

Day of German Unity

To commemorate the day that marks the official unification of the former East and West Germany in 1990, 3 October has since then been the official German national holiday, the Day of German Unity (Tag der deutschen Einheit). It replaced the previous national holiday held in West Germany on 17 June commemorating the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany and the national holiday on 7 October in the GDR, that commemorated the foundation of the East German state.[6]

Foreign support and opposition

For decades, West Germany's allies had stated their support for reunification. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who speculated that a country that "decided to kill millions of Jewish people" in the Holocaust "will try to do it again", was one of the few world leaders to publicly oppose it. As reunification became a realistic possibility, however, significant NATO and European opposition emerged in private.[19]

A poll of four countries in January 1990 found that a majority of surveyed Americans and French supported reunification, while British and Poles were more divided. 69% of Poles and 50% of French and British stated that they worried about a reunified Germany becoming "the dominant power in Europe". Those surveyed stated several concerns, including Germany again attempting to expand its territory, a revival of Nazism, and the German economy becoming too powerful. While British, French and Americans favored Germany remaining a member of NATO, a majority of Poles supported neutrality for the reunified nation.[20]

Britain and France

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher told Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev that neither the United Kingdom nor Western Europe wanted the reunification of Germany. Thatcher also clarified that she wanted the Soviet leader to do what he could to stop it, telling Gorbachev "We do not want a united Germany".[21] Although she welcomed East German democracy, Thatcher worried that a rapid reunification might weaken Gorbachev,[22] and favoured Soviet troops staying in East Germany as long as possible to act as a counterweight to a united Germany.[19]

We defeated the Germans twice! And now they're back!

— Margaret Thatcher, December 1989[23]

Thatcher, who carried in her handbag a map of Germany's 1937 borders to show others the "German problem", feared that its "national character", size and central location in Europe would cause the nation to be a "destabilizing rather than a stabilizing force in Europe".[22] In December 1989, she warned fellow European Community leaders at a Strasbourg summit that Kohl attended, "We defeated the Germans twice! And now they're back!"[23][19] Although Thatcher had stated her support for German self-determination in 1985,[22] she now argued that Germany's allies had only supported reunification because they had not believed it would ever happen.[19] Thatcher favoured a transition period of five years for reunification, during which the two Germanies would remain separate states. Although she gradually softened her opposition, as late as March 1990 Thatcher summoned historians and diplomats to a seminar at Chequers[22] to ask "How dangerous are the Germans?"[23] and the French ambassador in London reported that Thatcher had told him, "France and Great Britain should pull together today in the face of the German threat."[24][25]

The pace of events surprised the French, whose Foreign Ministry had concluded in October 1989 that reunification "does not appear realistic at this moment".[26] A representative of French President François Mitterrand reportedly told an aide to Gorbachev, "France by no means wants German reunification, although it realises that in the end it is inevitable."[21] At the Strasbourg summit, Mitterrand and Thatcher discussed the fluidity of Germany's historical borders.[19] On 20 January 1990, Mitterrand told Thatcher that a unified Germany could "make more ground than even Hitler had".[24] He predicted that "bad" Germans would reemerge,[23] who might seek to regain former German territory lost after World War II[22] and would likely dominate Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, leaving "only Romania and Bulgaria for the rest of us". The two leaders saw no way to prevent reunification, however, as "None of us was going to declare war on Germany".[19] Mitterrand recognized before Thatcher that reunification was inevitable and adjusted his views accordingly; unlike her, he was hopeful that participation in a single currency[22] and other European institutions could control a united Germany. Mitterrand still wanted Thatcher to publicly oppose unification, however, to obtain more concessions from Germany.[23]

Rest of Europe

I love Germany so much that I prefer to see two of them.

— Giulio Andreotti, Prime Minister of Italy[27]

Ireland's Taoiseach, Charles Haughey supported German Reunification and he took advantage of Ireland's presidency of the European Economic Community by calling for an extraordinary European summit in Dublin in April 1990 to calm fears held by fellow members of the EEC.[28][29][30] Haughey saw similarities between Ireland and Germany and cited "I have expressed a personal view that coming as we do from a country which is also divided many of us would have sympathy with any wish of the people of the two German States for unification".[31] Der Spiegel later described other European leaders' opinion of reunification at the time as "icy". Italy's Giulio Andreotti warned against a revival of "pan-Germanism" and joked "I love Germany so much that I prefer to see two of them", and the Netherlands' Ruud Lubbers questioned the German right to self-determination. They shared Britain and France's concerns over a return to German militarism and the economic power of a reunified nation. The consensus opinion was that reunification, if it must occur, should not occur until at least 1995 and preferably much later.[19][27]

Four powers

The United States – and President George H. W. Bush – recognized that Germany had gone through a long democratic transition. It had been a good friend, it was a member of NATO. Any issues that had existed in 1945, it seemed perfectly reasonable to lay them to rest. For us, the question wasn't should Germany unify? It was how and under what circumstances? We had no concern about a resurgent Germany...

— Condoleezza Rice, Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs[32]

The victors of World War II — France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States, comprising the Four-Power Authorities—retained authority over Berlin, such as control over air travel and its political status. From the onset, the Soviet Union sought to use reunification as a way to push Germany out of NATO into neutrality, removing nuclear weapons from its territory. However, West Germany misinterpreted a 21 November 1989 diplomatic message on the topic to mean that the Soviet leadership already anticipated reunification only two weeks after the Wall's collapse. This belief, and the worry that his rival Genscher might act first, encouraged Kohl on 28 November to announce a detailed "Ten Point Program for Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe". While his speech was very popular within West Germany, it caused concern among other European governments, with whom he had not discussed the plan.[19][33]

The Americans did not share the Europeans' and Russians' historical fears over German expansionism; Condoleezza Rice later recalled, "Any issues that had existed in 1945, it seemed perfectly reasonable to lay them to rest".[32] They wished to ensure, however, that Germany would stay within NATO. In December 1989, the administration of President George H. W. Bush made a united Germany's continued NATO membership a requirement for supporting reunification. Kohl agreed, although less than 20% of West Germans supported remaining within NATO; he also wished to avoid a neutral Germany, as he believed that would destroy NATO, cause the United States and Canada to leave Europe, and cause Britain and France to form an anti-German alliance. The United States increased its support of Kohl's policies, as it feared that otherwise Oskar Lafontaine, a critic of NATO, might become Chancellor.[19]

Horst Teltschik, Kohl's foreign policy advisor, later recalled that Germany would have paid "100 billion deutschmarks" had the Soviets demanded it. The USSR did not make such great demands, however, with Gorbachev stating in February 1990 that "The Germans must decide for themselves what path they choose to follow". In May 1990 he repeated his remark in the context of NATO membership while meeting Bush, amazing both the Americans and Germans.[19] This removed the last significant roadblock to Germany being free to choose its international alignments, though Kohl made no secret that he intended for the reunified Germany to inherit West Germany's seats in NATO and the EC.

Conclusion

During a NATO–Warsaw Pact conference in Ottawa, Canada, Genscher persuaded the four powers to treat the two Germanies as equals instead of defeated junior partners, and for the six nations to negotiate alone. Although the Dutch, Italians, Spanish, and other NATO powers opposed such a structure, which meant that the alliance's boundaries would change without their participation, the six nations began negotiations in March 1990. After Gorbachev's May agreement on German NATO membership, the Soviets further agreed that Germany would be treated as an ordinary NATO country, with the exception that former East German territory would not have foreign NATO troops or nuclear weapons. In exchange, Kohl agreed to reduce the sizes of both Germanies' militaries, renounce weapons of mass destruction, and accept the postwar Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern border. In addition, Germany agreed to pay about 55 billion deutschmarks to the Soviet Union in gifts and loans, the equivalent of eight days of the West German GDP.[19]

The British insisted to the end, against Soviet opposition, that NATO be allowed to hold maneuvers in the former East Germany. After the Americans intervened,[19] both the UK and France ratified the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in September 1990, thus finalizing the reunification for purposes of international law. Thatcher later wrote that her opposition to reunification had been an "unambiguous failure".[22]

Aftermath

German sovereignty, confirmation of borders, withdrawal of the Allied Forces

On 14 November 1990, the united Germany and Poland signed the German–Polish Border Treaty, finalizing Germany's boundaries as permanent along the Oder–Neisse line, and thus, renouncing any claims to Silesia, East Brandenburg, Farther Pomerania, and the southern area of the former province of East Prussia.[34] The treaty also granted certain rights for political minorities on either side of the border.[35] The following month, the first all-German free elections since 1932 were held, resulting in an increased majority for the coalition government of Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

On 15 March 1991, the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany—that had been signed in Moscow back on 12 September 1990 by the two German states that then existed (East and West Germany) on one side, and by the four principal Allied powers (the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union and the United States) on the other—entered into force, having been ratified by the Federal Republic of Germany (after the unification, as the united Germany) and by the four Allied nations. The entry into force of that treaty (also known as the "Two Plus Four Treaty", in reference to the two German states and four Allied nations that signed it) put an end to the then-remaining limitations on German sovereignty that resulted from the post World War II arrangements.

Under that treaty (which should not be confused with the Unification Treaty that was signed only between the two German states), the last Allied forces still present in Germany left in 1994, in accordance with article 4 of the treaty, that set 31 December 1994 as the deadline for the withdrawal of the remaining Allied forces. The last to leave were the Russians. The bulk of the Russian ground forces left Germany on 25 June 1994 with a military parade of the 6th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade in Berlin. The withdrawal of the last Russian troops was completed on 31 August 1994, and the event was marked by a military ceremony in the Treptow Park in Berlin.

As for the German–Polish Border Treaty, it was approved by the Polish Sejm on 26 November 1991 and the German Bundestag on 16 December 1991, and entered into force with the exchange of the instruments of ratification on 16 January 1992. The confirmation of the border between Germany and Poland was required of Germany by the Allied Powers in the Two Plus Four Treaty.

Cost of reunification

The subsequent economic restructuring and reconstruction of eastern Germany resulted in significant costs, especially for western Germany, which paid large sums of money in the form of the Solidaritätszuschlag (Solidarity Surcharge) in order to rebuild the east German infrastructure. Peer Steinbrück is quoted as saying in a 2011 interview, "Over a period of 20 years, German reunification has cost 2 trillion euros, or an average of 100 billion euros a year. So, we have to ask ourselves 'Aren't we willing to pay a tenth of that over several years for Europe's unity?'"[36]

Inner reunification

Vast differences between the former East Germany and West Germany in lifestyle, wealth, political beliefs, and other matters remain, and it is therefore still common to speak of eastern and western Germany distinctly. The eastern German economy has struggled since unification, and large subsidies are still transferred from west to east. The former East Germany area has often been compared to the underdeveloped Southern Italy and the Southern United States during Reconstruction after the American Civil War. While the East German economy has recovered recently, the differences between East and West remain present.[37][38]

Politicians and scholars have frequently called for a process of "inner reunification" of the two countries and asked whether there is "inner unification or continued separation".[39] "The process of German unity has not ended yet", proclaimed Chancellor Angela Merkel, who grew up in East Germany, in 2009.[40] Nevertheless, the question of this "inner reunification" has been widely discussed in the German public, politically, economically, culturally, and also constitutionally since 1989.

Politically, since the fall of the Wall, the successor party of the former East German socialist state party has become a major force in German politics. It was renamed PDS, and, later, merged with the Western leftist party WASG to form the party The Left (Die Linke).

Constitutionally, the Basic Law (Grundgesetz), the West German constitution, provided two pathways for a unification. The first was the implementation of a new all-German constitution, safeguarded by a popular referendum. Actually, this was the original idea of the "Grundgesetz" in 1949: it was named a "basic law" instead of a "constitution" because it was considered provisional.[41] The second way was more technical: the implementation of the constitution in the East, using a paragraph originally designed for the West German states (Bundesländer) in case of internal re-organization like the merger of two states. While this latter option was chosen as the most feasible one, the first option was partly regarded as a means to foster the "inner reunification".[42][43]

A public manifestation of coming to terms with the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) is the existence of the so-called Birthler-Behörde, the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records, which collects and maintains the files of the East German security apparatus.[44]

The economic reconstruction of former Eastern Germany following the reunification required large amounts of public funding which turned some areas into boom regions, although overall unemployment remains higher than in the former West.[45] Unemployment was part of a process of deindustrialization starting rapidly after 1990. Causes for this process are disputed in political conflicts up to the present day. Most times bureaucracy and lack of efficiency of the East German Economy are highlighted and the de-industrialization seen as inevitable outcome of the "Wende". But many East German critics point out that it was the shock-therapy style of privatization which did not leave room for east German Enterprises to adapt and that alternatives like a slow transition had been possible.[46] Reunification did, however, lead to a large rise in the average standard of living in former Eastern Germany and a stagnation in the West as $2 trillion in public spending was transferred East.[47] Between 1990 and 1995, gross wages in the east rose from 35% to 74% of western levels, while pensions rose from 40% to 79%.[48] Unemployment reached double the western level as well.

In terms of media usage and reception, the country remains partially divided especially among the older generations. Mentality gaps between East and West persist, but so does sympathy.[40] Additionally, the daily-life exchange of Easterners and Westerners is not so large as expected.[49][50] Young people's knowledge of the former East Germany is very low.[51] Some people in Eastern Germany engage in "Ostalgie", which is a certain nostalgia for the time before the wall came down.[52]

Today, there are several prominent East Germans, including Kurt Masur, Michael Ballack, Katarina Witt, and Angela Merkel.

Reunified Berlin

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (October 2012) |

While the fall of the Berlin Wall had broad economic, political and social impacts globally, it also had significant consequence for the local urban environment. In fact, the events of 9 November 1989 saw East Berlin and West Berlin, two halves of a single city that had ignored one another for the better part of 40 years, finally "in confrontation with one another".[53] As expressed by Grésillon[54] "the fall of the Berlin Wall [marked] the end of 40 years of divided political, economic and cultural histories" and was "accompanied by a strong belief that [the city] was now back on its 'natural' way to become again a major metropolis"[55] In the context of urban planning, in addition to a wealth of new opportunity and the symbolism of two former independent nations being re-joined, the reunification of Berlin presented numerous challenges. The city underwent massive redevelopment, involving the political, economic and cultural environment of both East and West Berlin. However, the "scar" left by the Wall, which ran directly through the very heart of the city[56] had consequences for the urban environment that planning still needs to address. Despite planning efforts, significant disparity between East and West remain.

Urban planning issues

The reunification of Berlin presented legal, political and technical challenges for the urban environment. The political division and physical separation of the city for more than 30 years saw the East and the West develop their own distinct urban forms, with many of these differences still visible to this day.[57] East and West Berlin were directed by two separate political and urban agendas. East Berlin developed a mono-centric structure with lower level density and a functional mix in the city's core, while West Berlin was poly-centric in nature, with a high-density, multi-functional city centre.[58] The two political systems allocated funds to post-war reconstruction differently, based on political priorities,[59] and this had consequences for the reunification of the city. West Berlin had received considerably more financial assistance for reconstruction and refurbishment.[59] There was considerable disparity in the general condition of many of the buildings; at the time of reunification, East Berlin still contained many leveled areas, which were previous sites of destroyed buildings from World War II, as well as damaged buildings that had not been repaired.[59] An immediate challenge facing the reunified city was the need for physical connectivity between the East and the West, specifically the organisation of infrastructure.[59] In the period following World War II, approximately half of the railway lines were removed in East Berlin.[60]

Policy for reunification

As urban planning in Germany is the responsibility of city government,[59] the integration of East and West Berlin was in part complicated by the fact that the existing planning frameworks became obsolete with the fall of the Wall.[61] Prior to the reunification of the city, the Land Use Plan of 1988 and General Development Plan of 1980 defined the spatial planning criteria for West and East Berlin, respectively.[61] Although these existing frameworks were in place before reunification, after the fall of the Wall there was a need to develop new instruments in order to facilitate the spatial and economic development of the re-unified city. The first Land Use Plan following reunification was ultimately enacted in 1994.[61] The urban development policy of reunified Berlin, termed "Critical Reconstruction", aimed to facilitate urban diversity by supporting a mixture of land functions.[55] This policy directed the urban planning strategy for the reunified city. A "Critical Reconstruction" policy agenda was to redefine Berlin's urban identity through its pre-war and pre-Nazi legacy. Elements of "Critical Reconstruction" were also reflected in the overall strategic planning document for downtown Berlin, entitled "Inner City Planning Framework".[55] Reunification policy emphasised restoration of the traditional Berlin landscape. To this effect, the policy excluded the "legacy of socialist East Berlin and notably of divided Berlin from the new urban identity".[55] Ultimately, following the collapse of the German Democratic Republic on 3 October 1990, all planning projects under the socialist regime were abandoned.[62] Vacant lots, open areas and empty fields in East Berlin were subject to redevelopment, in addition to space previously occupied by the Wall and associated buffering zone.[59] Many of these sites were positioned in central, strategic locations of the reunified city. The removal of the Wall saw the city's spatial structure reoriented.[61]

After the fall of the wall

Berlin's urban organisation experienced significant upheaval following the physical and metaphorical collapse of the Wall, as the city sought to "re-invent itself as a 'Western' metropolis".[55]

Redevelopment of vacant lots, open areas and empty fields as well as space previously occupied by the Wall and associated buffering zone[59] were based on land use priorities as reflected in "Critical Reconstruction" policies. Green space and recreational areas were allocated 38% of freed land; 6% of freed land was dedicated to mass-transit systems to address transport inadequacies.[59]

Reunification initiatives also included construction of major office and commercial projects, as well as the renovation of housing estates in East Berlin.

Another key priority was reestablishing Berlin as the capital of Germany, and this required buildings to serve government needs, including the "redevelopment of sites for scores of foreign embassies".[59]

With respect to redefining the city's identity, emphasis was placed on restoring Berlin's traditional landscape. "Critical Reconstruction" policies sought to disassociate the city's identity from its Nazi and socialist legacy, though some remnants were preserved, with walkways and bicycle paths established along the border strip to preserve the memory of the Wall.[59] In the centre of East Berlin much of the modernist heritage of the East German state was gradually removed.[62] Reunification saw the removal of politically motivated street names and monuments in the East (Large 2001) in an attempt to reduce the socialist legacy from the face of East Berlin.[55]

Immediately following the fall of the Wall, Berlin experienced a boom in the construction industry.[57] Redevelopment initiatives saw Berlin turn into one of the largest construction sites in the world through the 1990s and early 2000s.[61]

The fall of the Berlin Wall also had economic consequences. Two German systems covering distinctly divergent degrees of economic opportunity suddenly came into intimate contact.[63] Despite development of sites for commercial purposes, Berlin struggled to compete in economic terms with key West German centres such as Stuttgart and Düsseldorf.[64][65] The intensive building activity directed by planning policy resulted in the over-expansion of office space, "with a high level of vacancies in spite of the move of most administrations and government agencies from Bonn"[66][67]

Berlin was marred by disjointed economic restructuring, associated with massive deindustrialisation.[64][65] Economist Hartwich asserts that while the East undoubtedly improved economically, it was "at a much slower pace than [then Chancellor Helmut] Kohl had predicted".[68] Wealth and income inequality between former East and West Germany continues today even after reunification. On average adults in the former West Germany have assets worth 94,000 euros as compared to the adults in the former communist East Germany which have just over 40,000 euros in assets.[69]

Facilitation of economic development through planning measures failed to close the disparity between East and West, not only in terms of the economic opportunity but also housing conditions and transport options.[57] Tölle states that "the initial euphoria about having become one unified people again was increasingly replaced by a growing sense of difference between Easterners ("Ossis") and Westerners ("Wessis")"[70] The fall of the Wall also instigated immediate cultural change.[54] The first consequence was the closure in East Berlin of politically oriented cultural institutions.[54]

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the factors described above led to mass migration from East Berlin and East Germany, producing a large labour supply shock in the West.[63] Emigration from the East, totaling 870,000 people between 1989 and 1992 alone,[71] led to worse employment outcomes for the least-educated workers, for blue-collar workers, for men and for foreign nationals[63]

At the close of the century, it became evident that despite significant investment and planning, Berlin was yet to retake "its seat between the European Global Cities of London and Paris."[55] Yet ultimately, the disparity between East and West portions of Berlin has led to the city achieving a new urban identity.

A number of locales of East Berlin, characterised by dwellings of in-between use of abandoned space for little to no rent, have become the focal point and foundation of Berlin's burgeoning creative activities.[72] According to Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit, "the best that Berlin has to offer, its unique creativity. Creativity is Berlin's future."[73] Overall, the Berlin government's engagement in creativity is strongly centered on marketing and promotional initiatives instead of creative production.[74]

Creativity has been the catalyst for the city's "thriving music scene, active nightlife, and bustling street scene"[75] all of which have become important attractions for the German capital. The industry is a key component of the city's economic make-up with more than 10% of all Berlin residents employed in cultural sectors.[76]

Comparison

Germany was not the only state that had been separated through the aftermaths of World War II. For example, Korea as well as Vietnam have been separated through the occupation of "Western-Capitalistic" and "Eastern-Communistic" forces, after the defeat of the Japanese Empire. Both countries suffered severely from this separation in the Korean War (1950–53) and the Vietnam War (1955–75) respectively, which caused heavy economic and civilian damage.[77][78] However, German separation did not result in another war. Moreover, Germany is the only one of these countries that has managed to achieve a peaceful reunification. For instance, Vietnam achieved reunification only at the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, while North and South Korea still struggle with high political tensions and huge economical disparities, making a possible reunification an enormous challenge.[79]

See also

- History of Germany since 1945

- Reunification

- Stalin Note – 1952 German reunification proposal

- Transitology

- Good Bye, Lenin!

- Chinese Unification

- Cypriot reunification

- Irish reunification

- Korean reunification

- Yemeni unification

References

- ^ a b c Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands (Einigungsvertrag) Unification Treaty signed by the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic in Berlin on 31 August 1990 (official text, in German).

- ^ "DRA: Archivnachweise". 9 June 2009.

- ^ "GHDI - Document".

- ^ "Vertrag über die Schaffung einer Währungs-, Wirtschafts- und Sozialunion zwischen der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland". Die Verfassungen in Deutschland. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ German Unification Monetary union. Cepr.org (1 July 1990). Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany London – A short history of German reunification. London.diplo.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ http://www.mdr.de/damals/artikel99678.html

- ^ Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. "Volkskammer der DDR stimmt für Beitritt".

- ^ https://www.bundesarchiv.de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/bilder_dokumente/01525/index-16.html.de East German Resolution of Accesion to West Germany

- ^ "Bundesarchiv - Digitalisierung und Onlinestellung des Bestandes DA 1 Volkskammer der DDR, Teil 10. Wahlperiode".

- ^ "United States and Soviet Union Sign German Reunification Treaty" (PDF). NBC Learn. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Merkel to mark 20th anniversary of German reunification treaty". Deutschland.de. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Soviet Legislature Ratifies German Reunification Treaty". AP News Archive. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Opening of the Berlin Wall and Unification: German History. Germanculture.com.ua. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Bundesarchiv - Digitalisierung und Onlinestellung des Bestandes DA 1 Volkskammer der DDR, Teil 10. Wahlperiode".

- ^ "EinigVtr - Einzelnorm".

- ^ Germany Today – The German Unification Treaty – travel and tourist information, flight reservations, travel bargains, hotels, resorts, car hire. Europe-today.com. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ "File:Zwei-Plus-Vier-Vertrag.pdf" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wiegrefe, Klaus (29 September 2010). "An Inside Look at the Reunification Negotiations". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Skelton, George (26 January 1990). "THE TIMES POLL : One Germany: U.S. Unfazed, Europeans Fret". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ a b Michael Binyon (11 September 2009). "Thatcher told Gorbachev Britain did not want German reunification". The Times. London. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kundnani, Hans (28 October 2009). "Margaret Thatcher's German war". The Times. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Volkery, Carsten (9 November 2009). "The Iron Lady's Views on German Reunification/'The Germans Are Back!'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ a b Anne-Laure Mondesert (AFP) (31 October 2009). "London and Paris were shocked by German reunification". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ Peter Allen (2 November 2009). "Margaret Thatcher was 'horrified' by the prospect of a reunited Germany". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ Knight, Ben (8 November 2009). "Germany's neighbors try to redeem their 1989 negativity". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ a b Folli, Stefano (7 May 2013). "The Incarnation of Politics Is Gone". Il Sole 24 Ore. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ European Commission, Press Release Database, Dublin Summit, April 28, 1990, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_DOC-90-1_en.htm?locale=en

- ^ The European Council, Dublin, 28 April 1990, http://aei.pitt.edu/1397/1/Dublin_april_1990.pdf

- ^ Germany will Never Forget Ireland's Help, Irish Times, http://www.irishtimes.com/news/germany-will-never-forget-ireland-s-help-1.658399

- ^ German Reunification, Houses of the Oireachtas, Dáil Éireann, http://debates.oireachtas.ie/dail/1989/12/13/00007.asp

- ^ a b "'I Preferred To See It as an Acquisition'". Der Spiegel. 29 September 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Kohl, Helmut; Riemer, Jeremiah (translator). "Helmut Kohl's Ten-Point Plan for German Unity (November 28, 1989)". German History in Documents and Images. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The territory of the League of Nations mandate of the Free City of Danzig, annexed by Poland in 1945 and comprising the city of Gdańsk (Danzig) and a number of neighbouring cities and municipalities, had never been claimed by any official side, because West Germany followed the legal position of Germany in its borders of 1937, thus before any Nazi annexations.

- ^ Poland Germany border – Oder Neisse. Polandpoland.com (14 November 1990). Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ Interview with Peer Steinbrück in Der Spiegel

- ^ "Underestimating East Germany". The Atlantic. 6 November 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ After the fall 20 years ago this week the crumbling of the Berlin Wall began an empire s end. Anniston Star. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ National identity in eastern Germany ... .Google Books (30 October 1990). Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b Template:De icon Umfrage: Ost- und Westdeutsche entfernen sich voneinander – Nachrichten Politik – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ In fact, a new constitution was drafted by a "round table" of dissidents and delegates from East German civil society only to be discarded later, a fact that upset many East German intellectuals. See Volkmar Schöneburg: Vom Ludergeruch der Basisdemokratie. Geschichte und Schicksal des Verfassungsentwurfes des Runden Tisches der DDR, in: Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. II/2010.

- ^ Gastbeitrag: Nicht für die Ewigkeit – Staat und Recht – Politik. Faz.Net. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, Nr. 18 2009, 27 April 2009 – Das Grundgesetz – eine Verfassung auf Abruf?. Das-parlament.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ DDR-Geschichte: Merkel will Birthler-Behörde noch lange erhalten. Spiegel.de (15 January 2009). Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Facts about Germany: Society. Tatsachen-ueber-deutschland.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ For example the economist Jörg Roesler - see: Jörg Roesler: Ein Anderes Deutschland war möglich. Alternative Programme für das wirtschaftliche Zusammengehen beider deutscher Staaten, in: Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. II/2010, pp.34-46. The historian Ulrich Busch pointed out that the currency union as such had come to early- see Ulrich Busch: Die Währungsunion am 1. Juli 1990: Wirtschaftspolitische Fehlleistung mit Folgen, in: Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. II/2010, pp.5-24.

- ^ Sauga, Michael (6 September 2011). Designing a Transfer Union to Save the Euro.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Parkes, K. Stuart (1997). Understanding contemporary Germany. Taylor & Francis. p. 209. ISBN 0-415-14124-9.

- ^ Template:De icon Ostdeutschland: Das verschmähte Paradies | Campus | ZEIT ONLINE. Zeit.de (29 September 2008). Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ Template:De icon Partnerschaft: Der Mythos von den Ost-West-Ehepaaren – Nachrichten Panorama – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ Politics and History – German-German History – Goethe-Institut. Goethe.de. Retrieved on 19 October 2010.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (7 October 2003). "German Ostalgie: Fondly recalling the bad old days". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Grésillon, B (April 1999). "Berlin, cultural metropolis: Changes in the cultural geography of Berlin since reunification". ECUMENE. 6: 284–294. doi:10.1191/096746099701556286.

- ^ a b c Grésillon, B (April 1999). "Berlin, cultural metropolis: Changes in the cultural geography of Berlin since reunification". ECUMENE: 284.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tölle, A (2010). "Urban identity policies in Berlin: From critical reconstruction to reconstructing the Wall". Institute of Socio-Economic Geography and Spatial Management. 27: 348–357. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.04.005.

- ^ Hartwich, O. M. (2010). "After the Wall: 20 years on. Policy". 25 (4): 8–11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2003). Urban renaissance [electronic resource]: Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy for social cohesion and economic development / organisation for economic co-operation and development. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- ^ Schwedler, Hanns-Uve. "Divided cities - planning for unification". European Academy of the Urban Environment. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Loeb, Carolyn (January 2006). "Planning reunification: the planning history of the fall of the Berlin Wall" (PDF). Planning Perspectives. 21: 67–87. doi:10.1080/02665430500397329. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ MacDonogh, G (1997). Berlin. Great Britain: Sinclair-Stevenson. pp. 456–457.

- ^ a b c d e Schwedler, Hanns-Uve (2001). Urban Planning and Cultural Inclusion Lessons from Belfast and Berlin. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-79368-8.

- ^ a b Urban, F (2007). "Designing the past in East Berlin before and after the German Reunification". Progress in Planning. 68: 1–55. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2007.07.001.

- ^ a b c Frank, D. H. (13 May 2007). "The Effect of Migration on Natives' Employment Outcomes: Evidence from the Fall of the Berlin Wall". INSEAD Working Papers Selection.

- ^ a b Krätke, S (2004). "City of talents? Berlin's regional economy, socio-spatial fabric and "worst practice" urban governance". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 28 (3): 511–529. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00533.x.

- ^ a b Häußermann, H; Kapphan (2005). "Berlin: from divided to fragmented city. Transformation of Cities in Central and Eastern Europe. Towards Globalization". United Nations University Press: 189–222.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2003). Urban renaissance [electronic resource]: Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy for social cohesion and economic development / organisation for economic co-operation and development. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2003). Urban renaissance [electronic resource]: Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy for social cohesion and economic development / organisation for economic co-operation and development. Paris: OECD Publishing. p. 20.

- ^ Hartwich, O. M. (2010). "After the Wall: 20 years on. Policy". 25 (4): 8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Germany's wealth distribution most unequal in euro zone: study". Reuters. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Tölle, A (2010). "Urban identity policies in Berlin: From critical reconstruction to reconstructing the Wall". Institute of Socio-Economic Geography and Spatial Management. 27: 352. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.04.005.

- ^ Smith, E. O. (1994). The German Economy. London: Routledge. p. 266.

- ^ Jakob, D., 2010. Constructing the creative neighbourhood: hopes and limitations of creative city policies in Berlin. City, Culture and Society, 1, 4, December 2011, 193–198., D (December 2010). "Constructing the creative neighbourhood: hopes and limitations of creative city policies in Berlin". City, Culture and Society. 1 (4): 193–198. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2011.01.005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jakob, D. (December 2010). "Constructing the creative neighbourhood: hopes and limitations of creative city policies in Berlin". City, Culture and Society. 1 (4): 193–198. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2011.01.005.

- ^ Presse- und Informationsamt des Landes Berlin Berlin: Pressemitteilung, Presse- und Informationsamt des Landes. (2007). "Wowereit präsentierte den "Berlin Day" in New York".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Florida, R. L. (2005). Cities and the creative class. New York: Routledge. p. 99.

- ^ Senatsverwaltung für Wirtschaft Arbeit und Frauen in Berlin (2009). "Kulturwirtschaft in Berlin. Entwicklungen und Potenziale. Berlin: Senatsverwaltung für Wirtschaft Arbeit und Frauen in Berlin".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Korean War

- ^ Vietnam War

- ^ Bruce W. Bennett (2013). Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse (Report). RAND Corporation. p. XV.

There is a reasonable probability that North Korean totalitarianism will end in the foreseeable future, with the very strong likelihood that this end will be accompanied by considerable violence and upheaval.

{{cite report}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Maier, Charles S., Dissolution: The Crisis of Communism and the End of East Germany (Princeton University Press, 1997).

- Zelikow, Philip and Condoleezza Rice, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft (Harvard University Press, 1995 & 1997).

- Jarausch, Konrad H., and Volker Gransow, eds. Uniting Germany: Documents and Debates, 1944–1993 (1994), primary sources in English translation

External links

- The Unification Treaty (Berlin, 31 August 1990) website of CVCE (Centre of European Studies)

- Hessler, Uwe, "The End of East Germany", dw-world.de, 23 August 2005.

- Berg, Stefan, Steffen Winter and Andreas Wassermann, "Germany's Eastern Burden: The Price of a Failed Reunification", Der Spiegel, 5 September 2005.

- Wiegrefe, Klaus, "An Inside Look at the Reunification Negotiations"Der Spiegel, 29 September 2010.

- German Embassy Publication, Infocus: German Unity Day

- Problems with Reunification from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives