History of webcomics

The history of webcomics follows the advances of technology, art, and business of comics on the Internet. The first comics were shared through the Internet in the mid-1980s. Early webcomics were usually derivatives from strips in college newspapers, but when the World Wide Web became widely popular in the mid-1990s, more people started creating comics exclusively for this medium. By the year 2000, various webcomic creators were financially successful and webcomics became more artistically recognized.

In the second half of the 2000s, webcomics became less financially sustainable due to the rise of social media and consumers' disinterest in certain kinds of merchandise. However, crowdsourcing through Kickstarter and Patreon also became popular in this period, allowing readers to donate money to webcomic creators directly. The 2010s also saw the rise of webtoons in South Korea, where the form has become very prominent.

Early history (1985—1995)

Predating the sharing of graphics on the Internet, an artist going by the name Eerie created a comic on the Internet using ANSI art, titled Inspector Dangerfuck.[2][3] The earliest known graphical comic distributed solely through the Internet was Eric Millikin's Witches and Stitches, which he started uploading on CompuServe in 1985. By self-publishing on the Internet, Millikin was able to share his work without having to worry over censorship and demographics.[4][5] In 1986, Joe Ekaitis first uploaded T.H.E. Fox on CompuServe, a furry webcomic drawn on his Commodore 64.[6][7]

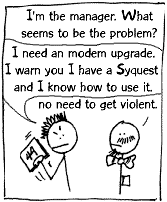

In the early 1990s, it was yet unclear which Internet protocol would dominate the market in coming years. Hans Bjohrdal's Where the Buffalo Roam was shared through Usenet in 1992. With this technology, Bjohrdal reached an audience at college campuses a few U.S. states across. Tim Berners-Lee's World Wide Web rose in popularity in 1993: usage of the World Wide Web grew by 341,634% in 1993, and competitor protocol Gopher's growth of 997% paled in comparison. Web browser Mosaic, which saw its beta release in 1993, allowed the recent introductions of GIF and JPEG image formats to be shown directly on web pages. Before this point, images shared through the internet had to be downloaded to the user's hard drive directly in order to be viewed.[1][8]

In 1994 and 1995, webcomics such as Jax & Co., NetBoy, and Argon Zark! experimented with forms possible only on the Internet, uploading strips in shapes and sizes impossible in print. Mike Wean's Jax & Co. introduced a "page turning" interface that encourages readers to read the panels in order; a concept that was quickly recreated by other webcomic artists.[10][11]

Reinder Dijkhuis recalled that, by the end of 1995, there were hundreds of comics being shared through the Internet. Most of these were derived from strips of college newspapers and zines, and most were short-lived on the Internet.[12] As Dilbert became the first syndicated comic strip to be published on the Internet in 1995, "[lending] a certain legitimacy to the online comic concept," it became clear the Internet could be an effective tool to reach large audiences.[13]

Rise to popularity (1995—2005)

In 2000, Scott McCloud released Reinventing Comics, a book in which he argued that the future of comics was on the Internet. McCloud stated that the World Wide Web allowed comics to make use of the various advantages of digital media, establishing the idea of infinite canvas. By 2008, it was clear that McCloud's predictions of infinite canvas did not materialize entirely,[14][15] but creators such as Cayetano Garza and Demian5 were influenced by his ideas.[10]

In 1997, Bryan McNett started a webcomic hosting provider, calling it Big Panda. Over 770 webcomics were hosted on Big Panda, including Sluggy Freelance, making it the first major webcomic portal. Due to a lack of interest, McNett shut Big Panda down in 2000. Chris Crosby, who ran his webcomic Superiosity on Big Panda at the time, contacted McNett in order to create a new webcomics portal, which resulted in Keenspot. This new portal became a major success.[8]

In 2002, Joey Manley started webcomic portal Modern Tales as a competitor to Keenspot, which became one of the first profitable subscription models for webcomics. According to T Campbell, webcomics seemed unsustainable at the time, with advertisement rates dropping to an all-time low. Manley's Modern Tales was a popular solution at the time, and Manley spun off websites such as Girlamatic and Webcomics Nation.[16] Modern Tales had 2,000 members by 2005, each paying $3 USD per month. In the same year, Keenspot drew in around 125,000 readers per day, grossing over $200,000 USD per year through advertising.[17] Established comic artists such as Carla Speed McNeil and Lea Hernandez found themselves moving towards the Internet in order to reach larger audiences and build "online portfolios".[15]

With the proliferation of webcomics, awards began to emerge. In 2000, the Eagle Awards introduced the "Favourite Web-based Comic" category, and 2001 saw the first installment of the Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards. The Ignatz Awards also added a "Best Online Comic" accolade in 2001, but the event was canceled this year due to the September 11 attacks and the title was first awarded in 2002. The Eisner Awards, the most prestigious comics ceremony, eventually introduced a "Best Digital Comic" category in 2005.[8]

Video game webcomics

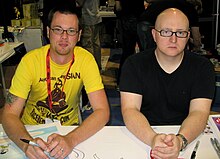

The second half of the 1990s saw the introduction of video game webcomics as a genre. Chris Morrison posted the first known video game webcomic, titled Polymer City Chronicles, in 1995. However, the genre wasn't popularized until Scott Kurtz started PvP in May 1998. In September the same year, the concept of sprite comics was introduced by Jay Resop's Neglected Mario Characters.[9] In November 1998, the duo of Jerry Holkins and Mike Krahulik started Penny Arcade, a comic Nich Maragos from 1UP.com described as the "most popular, the most lucrative, and the most influential" video game webcomics,[18] and by Mike Meginnis as "one of the most commonly emulated comics out there."[19]

Penny Arcade also proved to be a huge player in fields outside of webcomics in the early 2000s. In 2003, Holkins and Krahulik founded Child's Play, a charity that managed to raise over $100,000 USD in its first year, which it used for donating toys for the Seattle Children's Hospital. The charity has become more successful since and now donates toys to hospitals across the country. In 2004, the duo started the Penny Arcade Expo (PAX), a yearly video game convention that debuted with an estimated 3,000 guests and has grown in size since.[18][20]

David Anez' Bob and George, which launched in April 2000, was the first sprite comic to reach a larger level of popularity. However, it wouldn't be until the release of Brian Clevinger's 8-Bit Theater that the genre really took off. Maragos of 1-UP.com stated that 8-Bit Theater "took the style to its fullest expression and greatest popularity."[21] Larry Cruz of Comic Book Resources pointed out that, though sprite comics are still an overwhelmingly popular style, "no other sprite comic [has] really achieve[d] the same amount of popularity" since 8-Bit Theater's discontinuation in 2010.[22]

Modern era (2005—)

Bradly Dale from The New York Observer noted in 2015 that people in the American webcomics industry had been shifting their business practices. While during the early 2000s, webcomics were mainly reliant on merchandise such as T-shirts for monetization, but this practice became less profitable in the 2010s. Dorothy Gambrell, creator of Cat and Girl, explained that the practice went well until "the great T-shirt crash of 2008." Webcomic merchandise distributor Topatoco started looking to provide more products than only T-shirts around 2010, while Ryan North's "Project Wonderful" aimed to improve webcomic-based advertisement.[23]

Though the 2008 financial crisis had only a minor impact on the webcomic industry, many webcomic artists have been looking for alternative employment in the 2010s. While Topatoco has been seeking work with video game developers, podcasters and other internet personalities, some creators moved on to other media entirely. Toothpaste for Dinner-creator Drew Fairweather, for instance, started focusing his energy on his blog and his career as a rapper in 2011, while the creators of Amazing Super Powers moved on to developing video games.[23]

My business is not a business in the sense of being a small and medium sized enterprise or even particularly entrepreneurial ... I make comics because I like the activity of writing and drawing. It is a self-sustaining, one-man enterprise.

Scary Go Round-creator John Allison[24]

With the rise of social media in the second half of the 2000s, webcomic artist began having a more difficult time gaining attention and views. Wondermark-creator David Malki believes traffic to webcomic websites plateaued in 2012, as visiting content-specific websites generally disappeared from people's daily routines. Sharing of comic strips on social media such as Facebook has led to more exposure of webcomics, causing some to show signs of growth, but few people access webcomic websites directly.[25]

In 2015, Gambrell stated that "webcomics are dead," as the period of webcomics only being posted for free on the internet was over and the industry had moved beyond the internet.[24] Though many successful webcomic creators in the 2010s do not envision their online craft as their "job", most do not have to worry about basic money issues.[24] However, Sarah Dorchak of Gauntlet proposed in 2011 that the free nature of webcomics may be a leading factor in the decline of economic viability of traditional comic books.[4]

Crowdsourcing

In 2004, R.K. Milholland's started a crowdsourcing project to stabilize the update schedule of his webcomic Something Positive. After fans donated enough money for Milholland to quit his job and focus exclusively on Something Positive, other webcomic creators followed his example.[26] Zack Weinersmith of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal turned to Kickstarter to fund his related project Single Use Monocles,[23] and Andrew Hussie's Hiveswap raised over $700,000 USD in 2012, becoming the most successful webcomic-related Kickstarter project of all time.[27] Creators of smaller webcomics such as Cucumber Quest and The Antler Boy frequently raise over $50,000 USD on Kickstarter in order to publish their material in print.[28]

Another large shift in the webcomic industry came with the 2013 introduction of Patreon, through which people can donate money directly to content creators. Weinersmith, North, Allison, and Dave McElfatrick have all pointed at the service as a turning point for the webcomic industry that allowed many artist to produce online comics full-time.[24]

Asian webcomics

The early 2010s saw the global increase in popularity of South Korean webtoons. Supported by high-speed Internet and large-scale mobile phone usage in South Korea, webtoons achieved a high demand. Webtoons have been adapted into TV dramas, films, online games and musicals, making it a multimillion-dollar market.[29] Tapastic, a comics portal that accepts English-translated webtoons as webcomics from other cultures, was founded in 2012. Naver Corporation, South Korea's largest inventory of webtoons, began offering them in English in 2014.[30]

Around the same period, Indian webcomics and Chinese webcomics also saw a large increase in popularity. Here, webcomics are often used as a vehicle for social or political reform.[31][32]

See also

References

- ^ a b Campbell (2006). pp. 10–13.

- ^ Campbell (2006). p. 10.

- ^ Aspray, William; Hayas, Barbara M. (2011). Everyday Information: The Evolution of Information Seeking in America. MIT Press. p. 298. ISBN 0262015013.

- ^ a b Dochak, Sarah (2011-11-29). "Pioneering the page: The decline of print comics, the growth of webcomics and the flexibility, innovation and controversy of both". Gauntlet.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Smith, Alexander, K. (2011-11-19). "14 Awesome Webcomics To Distract You From Getting Things Done". Paste.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joe Ekaitis (1994-12-04). "Meet Joe Ekaitis — T.H.E. FOX" (Interview). Interviewed by Sherry, accompanied by Lou Schonder.

- ^ Jeff Lowenthal (July 1989). "Public Domain". .info (27). Iowa City, Iowa: Info Publications: 59. ISSN 0897-5868. OCLC 17565429.

- ^ a b c Atchison (2008). part one

- ^ a b Maragos (2005). p. 1.

- ^ a b Garrity, Shaenon (2011-07-15). "The History of Webcomics". The Comics Journal.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Campbell (2006). pp. 18–19.

- ^ Campbell (2006). pp. 19–20.

- ^ Meginnis, Mike (2005). The Artistic History of Webcomics. "Scott Adams".

- ^ Boxer, Sarah (2005-08-17). "Comics Escape a Paper Box, and Electronic Questions Pop Out". The New York Times.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Atchison (2008). part two

- ^ Melrose, Kevin (2013-11-08). "Modern Tales founder Joey Manley passes away". Comic Book Resources.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Walker, Leslie (2005-06-16). "Comics Looking to Spread A Little Laughter on the Web". The Washington Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Maragos (2005). p. 4.

- ^ Meginnis, Mike (2005). The Artistic History of Webcomics. "Tycho and Gabe".

- ^ Atchison (2008). part three

- ^ Maragos (2005). p. 3.

- ^ Cruz, Larry (2014-05-09). "Will there ever be another great sprite comic?". Comic Book Resources.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Dale, Bradly (2015-11-16). "The Webcomics Business Is Moving on From Webcomics". The New York Observer.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Dale, Bradly (2015-11-19). "Lessons in Creativity From Successful Webcomic Artists". The New York Observer.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dale, Bradly (2015-11-18). "The Changing Internet Through Webcomics". The New York Observer.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dale, Bradly (2015-11-17). "Patreon, Webcomics and Getting By". The New York Observer.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Graeme McMillan (2012-09-06). "'Homestuck' heads towards new Kickstarter record". Digital Trends. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ^ Siegel, Mark R. (2012-10-08). "The New Serial Revolution". The Huffington Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "South Korean 'webtoon' craze makes global waves". The Japan Times. 2015-11-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lee, Jun-Youb (2015-04-03). "Startup Battles Naver in English Webtoons". The Wall Street Journal.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Verma, Tarishi (2015-04-26). "Laughing through our worries: The Indian web comics". Hindustan Times.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Langfitt, Frank (2012-03-16). "Provocative Chinese Cartoonists Find An Outlet Online". npr.org.

Bibliography

- Campbell, T. (2006-06-08). A History of Webcomics. Antarctic Press. ISBN 0976804395.

- Atchison, Lee (2008-01-07). "A Brief History of Webcomics — The Third Age of Webcomics". Sequential Tart.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - Maragos, Nick (2005-11-07). "Will Strip for Games". 1UP. Archived from the original on 2016-05-13.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Various (2005). "The Artistic History of Webcomics – A Webcomics Examiner Roundtable". The Webcomics Examiner. Archived from the original on 2005-11-24.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)