John Brown (abolitionist)

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2015) |

John Brown | |

|---|---|

An 1846 daguerreotype of Brown. | |

| Born | May 9, 1800 Torrington, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 1859 (aged 59) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | John Brown Farm State Historic Site, Lake Placid, New York, U.S. |

| Known for | Pottawatomie massacre Raid on Harpers Ferry |

| Children | 20 (11 survived to adulthood) |

| Signature | |

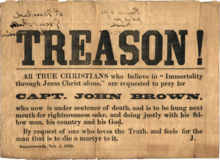

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist who believed armed insurrection was the only way to overthrow the institution of slavery in the United States.

During the 1856 conflict in Kansas, Brown commanded forces at the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie. Brown's followers killed five slavery supporters at Pottawatomie. In 1859, Brown led an unsuccessful raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry that ended with the multi-racial group's capture. Brown's trial resulted in his conviction and a sentence of death by hanging.

Brown's attempt in 1859 to start a liberation movement among enslaved African Americans in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (later part of West Virginia), electrified the nation. He was tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, the murder of five men and inciting a slave insurrection. He was found guilty on all counts and was hanged. Southerners alleged that his rebellion was the tip of the abolitionist iceberg and represented the wishes of the Republican Party to end slavery. Historians agree that the Harpers Ferry raid in 1859 escalated tensions that, a year later, led to secession and the American Civil War.

Brown first gained attention when he led small groups of volunteers during the Bleeding Kansas crisis. Unlike most other Northerners, who advocated peaceful resistance to the pro-slavery faction, Brown believed that peaceful resistance was shown to be ineffective and that the only way to defeat the oppressive system of slavery was through violent insurrection. He believed he was the instrument of God's wrath in punishing men for the sin of owning slaves. Dissatisfied with the pacifism encouraged by the organized abolitionist movement, he said, "These men are all talk. What we need is action—action!" During the Kansas campaign, he and his supporters killed five pro-slavery supporters in what became known as the Pottawatomie massacre in May 1856 in response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas by pro-slavery forces.

In 1859 he led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry. During the raid, he seized the armory; seven people were killed, and ten or more were injured. He intended to arm slaves with weapons from the arsenal, but the attack failed. Within 36 hours, Brown's men had fled or been killed or captured by local pro-slavery farmers, militiamen, and U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee. Brown's subsequent capture by federal forces seized the nation's attention, as Southerners feared it was just the first of many Northern plots to cause a slave rebellion that might endanger their lives, while Republicans dismissed the notion and claimed they would not interfere with slavery in the South.

Historians agree John Brown played a major role in the start of the Civil War. Historian David Potter has said the emotional effect of Brown's raid was greater than the philosophical effect of the Lincoln–Douglas debates, and that his raid revealed a deep division between North and South.[citation needed] Some writers, including Bruce Olds, describe him as a monomaniacal zealot; others, such as Stephen B. Oates, regard him as "one of the most perceptive human beings of his generation."[citation needed] David S. Reynolds hails him as the man who "killed slavery, sparked the civil war, and seeded civil rights" and Richard Owen Boyer emphasizes that Brown was "an American who gave his life that millions of other Americans might be free."[citation needed] The song John Brown's Body made him a martyr and was a popular Union marching song during the Civil War.

Brown's actions prior to the Civil War as an abolitionist, and the tactics he chose, still make him a controversial figure today. He is sometimes memorialized as a heroic martyr and a visionary, and sometimes vilified as a madman and a terrorist.

Early years

John Brown was born May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. He was the fourth of the eight children of Owen Brown (February 16, 1771 – May 8, 1856) and Ruth Mills (January 25, 1772 – December 9, 1808) and grandson of Capt. John Brown (1728–1776).[1] Brown could trace his ancestry back to 17th-century English Puritans.[2]

In 1805, the family moved to Hudson, Ohio, where Owen Brown opened a tannery. Brown's father became a supporter of the Oberlin Institute (original name of Oberlin College) in its early stage, although he was ultimately critical of the school's "Perfectionist" leanings, especially renowned in the preaching and teaching of Charles Finney and Asa Mahan. Brown withdrew his membership from the Congregational church in the 1840s and never officially joined another church, but both he and his father Owen were fairly conventional evangelicals for the period with its focus on the pursuit of personal righteousness. Brown's personal religion is fairly well documented in the papers of the Rev Clarence Gee, a Brown family expert, now held in the Hudson [Ohio] Library and Historical Society.[citation needed]

Brown's father had as an apprentice Jesse R. Grant, father of future general and U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant.[3] At the age of 16, Brown left his family and went to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where he enrolled in a preparatory program. Shortly afterward, he transferred to the Morris Academy in Litchfield, Connecticut.[4] He hoped to become a Congregationalist minister, but money ran out and he suffered from eye inflammations, which forced him to give up the academy and return to Ohio. In Hudson, he worked briefly at his father's tannery before opening a successful tannery of his own outside of town with his adopted brother.[citation needed]

In 1820, Brown married Dianthe Lusk. Their first child, John Jr, was born 13 months later. In 1825, Brown and his family moved to New Richmond, Pennsylvania, where he bought 200 acres (81 hectares) of land. He cleared an eighth of it and built a cabin, a barn, and a tannery. The John Brown Tannery Site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.[6] Within a year, the tannery employed 15 men. Brown made money raising cattle and surveying. He helped to establish a post office and a school. During this period, Brown operated an interstate business involving cattle and leather production along with a kinsman, Seth Thompson, from eastern Ohio.[citation needed]

In 1831, one of his sons died. Brown fell ill, and his businesses began to suffer, leaving him in terrible debt. In the summer of 1832, shortly after the death of a newborn son, his wife Dianthe died. On June 14, 1833, Brown married 16-year-old Mary Ann Day (April 15, 1817 – May 1, 1884), originally from Washington County, New York.[7] They eventually had 13 children, in addition to the seven children from his previous marriage.

In 1836, Brown moved his family to Franklin Mills, Ohio (now known as Kent). There he borrowed money to buy land in the area, building and operating a tannery along the Cuyahoga River in partnership with Zenas Kent.[8] He suffered great financial losses in the economic crisis of 1839, which struck the western states more severely than had the Panic of 1837. Following the heavy borrowing trends of Ohio, many businessmen like Brown trusted too heavily in credit and state bonds and paid dearly for it. In one episode of property loss, Brown was even jailed when he attempted to retain ownership of a farm by occupying it against the claims of the new owner. Like other determined men of his time and background, he tried many different business efforts in an attempt to get out of debt. Along with tanning hides and cattle trading, he also undertook horse and sheep breeding, the last of which was to become a notable aspect of his pre-public vocation.[citation needed]

In 1837, in response to the murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy, Brown publicly vowed: "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!"[9][failed verification] Brown was declared bankrupt by a federal court on September 28, 1842. In 1843, four of his children died of dysentery. As Louis DeCaro Jr shows in his biographical sketch (2007), from the mid-1840s Brown had built a reputation as an expert in fine sheep and wool, and entered into a partnership with Col. Simon Perkins of Akron, Ohio, whose flocks and farms were managed by Brown and sons. Brown eventually moved into a home with his family across the street from the Perkins Stone Mansion located on Perkins Hill. The John Brown House (Akron, Ohio) still stands and is owned and operated by The Summit County Historical Society of Akron, Ohio.

Transformative years in Springfield, Massachusetts

In 1846, Brown and his business partner Simon Perkins moved to the ideologically progressive city of Springfield, Massachusetts. In Springfield, Brown found a community whose white leadership – from the community's most prominent churches, to its most wealthy businessmen, to its most popular politicians, to its local jurists, and even to the publisher of one of the nation's most influential newspapers – were deeply involved and emotionally invested in the anti-slavery movement.[10] Brown and Perkins' intent was to represent the interests of the Connecticut River Valley's wool growers against the interests of the region's wool manufacturers – thus Brown and Perkins set up a wool commission operation. While in Springfield, Brown lived in a house at 51 Franklin Street.[11]

Two years before Brown's arrival in Springfield, in 1844, the city's African-American abolitionists had founded the Sanford Street "Free Church" – now known as St. John's Congregational Church – which went on to become one of the United States most prominent platforms for abolitionist speeches.[11] From 1846 until he left Springfield in 1850, John Brown was a parishioner at the Free Church, where he witnessed abolitionist lectures by Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.[12] Indeed, during Brown's time in Springfield, he became deeply involved in transforming the city into a major center of abolitionism, and one of the safest and most significant stops on the Underground Railroad. Brown's Bible is still on display at St. John's Congregational Church in Springfield, which to this day remains one of the Northeast's most prominent black churches.[13]

In 1847, after speaking at the "Free Church", abolitionist Frederick Douglass spent a night speaking with Brown, after which he wrote, "From this night spent with John Brown in Springfield, Mass. 1847 while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition. My utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man's strong impressions."[10]

While in Springfield, as Brown learned more about abolitionism and the Underground Railroad, he also learned more about the region's mercantile elite, knowledge which while initially a 'curse', proved ultimately to be a 'blessing' to Brown's later activities in Kansas and at Harper's Ferry. Springfield's mercantile elite reacted with hesitation to change their theretofore highly profitable formula of low-quality wool sold en masse for low prices. Initially, Brown naively trusted Springfield's manufacturers, but soon came to realize that they were determined to maintain their control of price-setting. Also, on the outskirts of Springfield, the Connecticut River Valley's sheep farmers were largely unorganized and hesitant to change their methods of production to meet higher standards.[citation needed]

In the Ohio Cultivator, Brown and other wool growers complained that the Connecticut River Valley's farmers' tendencies were lowering all U.S. wool prices abroad. In reaction, Brown made a last-ditch effort to overcome the Pioneer Valley's wool mercantile elite by seeking an alliance with European-based manufacturers. Ultimately, Brown was disappointed to learn that Europe wanted to buy Western Massachusetts's wools en masse at the cheap prices they'd been getting from them. Brown then traveled to England to seek a higher price for Springfield's wool. The trip was a disaster, as the firm incurred a loss of $40,000 (over $980,000 in today's dollars), of which Col. Perkins bore the larger share. With this misfortune, the Perkins and Brown wool commission operation closed in Springfield in late 1849. Subsequent lawsuits tied up the partners for several more years.[citation needed]

The Fugitive Slave Act and The League of Gileadites

Before Brown left Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1850, the United States passed the notorious Fugitive Slave Act, a law which mandated that authorities in free states aid in the return of escaped slaves and imposed penalties on those who aided in their escape. In response to the Fugitive Slave Act, John Brown founded a militant group to prevent slaves' capture – The League of Gileadites – in Springfield. In the Bible, Mount Gilead was the place where only the bravest of Israelites would gather together to face an invading enemy. Brown founded the League of Gileadites with these words, "Nothing so charmes the American people as personal bravery. [Blacks] would have ten times the number [of white friends than] they now have were they but half as much in earnest to secure their dearest rights as they are to ape the follies and extravagances of their white neighbors, and to indulge in idle show, in ease, and in luxury."[14]

Upon leaving Springfield in 1850, Brown instructed the League of Gileadites to act "quickly, quietly, and efficiently" to protect slaves that escaped to Springfield – words that would foreshadow Brown's later actions preceding Harper's Ferry.[14] It is worth noting that from Brown's founding of the League of Gileadites onward, not one person was ever taken back into slavery from Springfield. On leaving Springfield in 1850, Brown gave his rocking chair to the mother of his beloved black porter, Thomas Thomas, as a gesture of affection.[10]

Some popular narrators have exaggerated the unfortunate demise of Brown and Perkins' wool commission in Springfield with Brown's later life choices. In actuality, Perkins absorbed much of the financial loss, and their partnership continued for several more years, with Brown nearly breaking even by 1854. Brown's time in Springfield sowed the seeds for the future financial support that he would receive from New England's great merchants, introduced him to nationally famous abolitionists like Douglass and Truth, and included the foundation of his first militant anti-slavery group The League of Gileadites.[10][11] During this time, Brown also helped publicize David Walker's speech called Appeal.[15] Brown's personal attitudes evolved in Springfield, as he observed the success of the city's Underground Railroad and made his first venture into militant, anti-slavery community organizing. In speeches, he pointed to the martyrs Elijah Lovejoy and Charles Turner Torrey as whites "ready to help blacks challenge slave-catchers.".[16] In Springfield, Brown found a city that shared his own anti-slavery passions, and each seemed to educate the other. Certainly, with both successes and failures, Brown's Springfield years were a transformative period of his life, which catalyzed many of his later actions.[10]

Homestead in New York

In 1848, Brown heard of Gerrit Smith's Adirondack land grants to poor black men, and decided to move his family among the new settlers. He bought land near North Elba, New York (near Lake Placid), for $1 an acre ($2 /ha), and spent 2 years there.[17] After he was executed, his wife took his body there for burial. Since 1895, the farm has been owned by New York state.[18] The John Brown Farm and Gravesite is now a National Historic Landmark.

Actions in Kansas

In 1855, Brown learned from his adult sons in the Kansas territory that their families were completely unprepared to face attack, and that pro-slavery forces there were militant. Determined to protect his family and oppose the advances of slavery supporters, Brown left for Kansas, enlisting a son-in-law and making several stops just to collect funds and weapons. As reported by the New York Tribune, Brown stopped en route to participate in an anti-slavery convention that took place in June 1855 in Albany, New York. Despite the controversy that ensued on the convention floor regarding the support of violent efforts on behalf of the free state cause, several individuals provided Brown some solicited financial support. As he went westward, however, Brown found more militant support in his home state of Ohio, particularly in the strongly anti-slavery Western Reserve section where he had been reared.[citation needed]

Pottawatomie

Brown and the free settlers were optimistic that they could bring Kansas into the union as a slavery-free state.[19] After the winter snows thawed in 1856, the pro-slavery activists began a campaign to seize Kansas on their own terms. Brown was particularly affected by the sacking of Lawrence in May 1856, in which a sheriff-led posse destroyed newspaper offices and a hotel. Only one man, a Border Ruffian, was killed. Preston Brooks's caning of anti-slavery Senator Charles Sumner in the United States Senate also fueled Brown's anger. A pro-slavery writer, Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow, of the Squatter Sovereign, wrote that "[pro-slavery forces] are determined to repel this Northern invasion, and make Kansas a Slave State; though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims, and the carcasses of the Abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed disease and sickness, we will not be deterred from our purpose" (quoted in Reynolds, p. 162). Brown was outraged by both the violence of the pro-slavery forces, and what he saw as a weak and cowardly response by the antislavery partisans and the Free State settlers, whom he described as "cowards, or worse" (Reynolds, pp. 163–64).

Brown's beloved father, Owen, died on May 8, 1856. Correspondence indicates that John Brown and his family received word of his death around the same time. Brown conducted surveillance on encamped "ruffians" in his vicinity and learned that his family was marked for attack, and furthermore was given supposedly reliable information as to pro-slavery neighbors who had aligned and supported these forces. Speaking of the threats that were supposedly the justification for the massacre, Free State leader Charles Robinson stated, "When it is known that such threats were as plenty as blue-berries in June, on both sides, all over the Territory, and were regarded as of no more importance than the idle wind, this indictment will hardly justify midnight assassination of all pro-slavery men, whether making threats or not... Had all men been killed in Kansas who indulged in such threats, there would have been none left to bury the dead."[20]

The pro-slavery men did not necessarily own any slaves, although the Doyles (three of the victims) had been slave hunters prior to settling in Kansas.[citation needed] According to Salmon Brown, [who?] when the Doyles were seized, Mahala Doyle acknowledged that her husband's "devilment" had brought down this attack to their doorstep. Sometime after 10:00 pm May 24, 1856, it is suspected they took five pro-slavery settlers – James Doyle, William Doyle, Drury Doyle, Allen Wilkinson, and William Sherman – from their cabins on Pottawatomie Creek and hacked them to death with broadswords. Brown later claimed he did not participate in the killings, however he did say he approved of them.[citation needed]

In the two years prior to the Pottawatomie Creek massacre, there had been eight (8) killings in Kansas Territory attributable to slavery politics, but none in the vicinity of the massacre. The massacre was the match in the powder keg that precipitated the bloodiest period in "Bleeding Kansas" history, a three-month period of retaliatory raids and battles in which 29 people died.[21]

Palmyra and Osawatomie

A force of Missourians, led by Captain Henry Pate, captured John Jr. and Jason, and destroyed the Brown family homestead, and later participated in the Sack of Lawrence. On June 2, John Brown, nine of his followers, and twenty local men successfully defended a Free State settlement at Palmyra, Kansas against an attack by Pate (see Battle of Black Jack). Pate and twenty-two of his men were taken prisoner (Reynolds pp. 180–181, 186). After capture, they were taken to Brown's camp, and received all the food that Brown could find. Brown forced Pate to sign a treaty, exchanging the freedom of Pate and his men for the promised release of Brown's two captured sons. Brown released Pate to Colonel Edwin Sumner, but was furious to discover that the release of his sons was delayed until September.[citation needed]

In August, a company of over three hundred Missourians under the command of Major General John W. Reid crossed into Kansas and headed towards Osawatomie, Kansas, intending to destroy the Free State settlements there, and then march on Topeka and Lawrence.[22]

On the morning of August 30, 1856, they shot and killed Brown's son Frederick and his neighbor David Garrison on the outskirts of Osawatomie. Brown, outnumbered more than seven to one, arranged his 38 men behind natural defenses along the road. Firing from cover, they managed to kill at least 20 of Reid's men and wounded 40 more.[23] Reid regrouped, ordering his men to dismount and charge into the woods. Brown's small group scattered and fled across the Marais des Cygnes River. One of Brown's men was killed during the retreat and four were captured. While Brown and his surviving men hid in the woods nearby, the Missourians plundered and burned Osawatomie. Despite being defeated, Brown's bravery and military shrewdness in the face of overwhelming odds brought him national attention and made him a hero to many Northern abolitionists,[24] who gave him the nickname "Osawatomie Brown". This incident was dramatized in the play Osawatomie Brown.

On September 7, Brown entered Lawrence to meet with Free State leaders and help fortify against a feared assault. At least 2,700 pro-slavery Missourians were once again invading Kansas. On September 14, they skirmished near Lawrence. Brown prepared for battle, but serious violence was averted when the new governor of Kansas, John W. Geary, ordered the warring parties to disarm and disband, and offered clemency to former fighters on both sides.[25] Brown, taking advantage of the fragile peace, left Kansas with three of his sons to raise money from supporters in the North.[citation needed]

In late October, Brown made a stop at the Traveler's Rest, an inn kept by a Quaker named James Townsend in West Branch, Cedar County, Iowa. He asked Townsend, "Have you ever heard of John Brown of Kansas?" Mr. Townsend took out a piece of chalk and marked Mr. Brown's hat, back and mule with an 'X,' meaning he was added to the 'free list.' He left there on October 25, and headed to Chicago, then Ohio, New York and eventually to Boston.[26][27] Townsend would later be a pallbearer at Owen Brown's funeral.[28]

Later years

Gathering forces

By November 1856, Brown had returned to the East, and spent the next two years in New England raising funds. Initially, Brown returned to Springfield, where he received contributions, and also a letter of recommendation from a prominent and wealthy merchant, Mr. George Walker. George Walker was the brother-in-law of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, the secretary for the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, who later introduced Brown to several influential abolitionists in the Boston area in January 1857.[11][29] Amos Adams Lawrence, a prominent Boston merchant, secretly gave a large amount of cash. William Lloyd Garrison, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker and George Luther Stearns, and Samuel Gridley Howe also supported Brown. A group of six wealthy abolitionists – Sanborn, Higginson, Parker, Stearns, Howe, and Gerrit Smith – agreed to offer Brown financial support for his antislavery activities; they would eventually provide most of the financial backing for the raid on Harpers Ferry, and would come to be known as the Secret Six[30] and the Committee of Six. Brown often requested help from them with "no questions asked" and it remains unclear of how much of Brown's scheme the Secret Six were aware.[citation needed]

On January 7, 1858, the Massachusetts Committee pledged to provide 200 Sharps Rifles and ammunition, which were being stored at Tabor, Iowa. In March, Brown contracted Charles Blair of Collinsville, Connecticut for 1,000 pikes.[citation needed]

In the following months, Brown continued to raise funds, visiting Worcester, Springfield, New Haven, Syracuse and Boston. In Boston, he met Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He received many pledges but little cash. In March, while in New York City, he was introduced to Hugh Forbes, an English mercenary, who had experience as a military tactician that he gained while fighting with Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy in 1848. Brown hired him to be the drillmaster for his men and to write their tactical handbook. They agreed to meet in Tabor that summer. Using the alias Nelson Hawkins, Brown traveled through the Northeast and then went to visit his family in Hudson, Ohio. On August 7, he arrived in Tabor. Forbes arrived two days later. Over several weeks, the two men put together a "Well-Matured Plan" for fighting slavery in the South. The men quarreled over many of the details. In November, their troops left for Kansas. Forbes had not received his salary and was still feuding with Brown, so he returned to the East instead of venturing into Kansas. He would soon threaten to expose the plot to the government.[citation needed]

As the October elections saw a free-state victory, Kansas was quiet. Brown made his men return to Iowa, where he fed them tidbits of his Virginia scheme.[31] In January 1858, Brown left his men in Springdale, Iowa, and set off to visit Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. There he discussed his plans with Douglass, and reconsidered Forbes' criticisms.[32] Brown wrote a Provisional Constitution that would create a government for a new state in the region of his invasion. Brown then traveled to Peterboro, New York, and Boston to discuss matters with the Secret Six. In letters to them, he indicated that, along with recruits, he would go into the South equipped with weapons to do "Kansas work".[citation needed]

Brown and twelve of his followers, including his son Owen, traveled to Chatham, Ontario, where he convened on May 10 a Constitutional Convention.[33] The convention, with several dozen delegates including his friend James Madison Bell, was put together with the help of Dr. Martin Delany.[34] One-third of Chatham's 6,000 residents were fugitive slaves, and it was here that Brown was introduced to Harriet Tubman. The convention assembled 34 blacks and 12 whites to adopt Brown's Provisional Constitution. According to Delany, during the convention, Brown illuminated his plans to make Kansas rather than Canada the end of the Underground Railroad. This would be the Subterranean Pass Way.[citation needed] Delany's reflections are not entirely trustworthy. Brown was no longer looking toward Kansas and was entirely focused on Virginia. Other testimony from the Chatham meeting suggests Brown did speak of going South. Brown had long used the terminology of the Subterranean Pass Way from the late 1840s, so it is possible that Delany conflated Brown's statements over the years. Regardless, Brown was elected commander-in-chief and he named John Henrie Kagi as his "Secretary of War". Richard Realf was named "Secretary of State". Elder Monroe, a black minister, was to act as president until another was chosen. A.M. Chapman was the acting vice president; Delany, the corresponding secretary. In 1859, "A Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America" was written.[citation needed]

Although nearly all of the delegates signed the constitution, very few delegates volunteered to join Brown's forces, although it will never be clear how many Canadian expatriates actually intended to join Brown because of a subsequent "security leak" that threw off plans for the raid, creating a hiatus in which Brown lost contact with many of the Canadian leaders. This crisis occurred when Hugh Forbes, Brown's mercenary, tried to expose the plans to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and others. The Secret Six feared their names would be made public. Howe and Higginson wanted no delays in Brown's progress, while Parker, Stearns, Smith and Sanborn insisted on postponement. Stearns and Smith were the major sources of funds, and their words carried more weight. To throw Forbes off the trail and to invalidate his assertions, Brown returned to Kansas in June, and he remained in that vicinity for six months. There he joined forces with James Montgomery, who was leading raids into Missouri. On December 20, Brown led his own raid, in which he liberated eleven slaves, took captive two white men, and looted horses and wagons. On January 20, 1859, he embarked on a lengthy journey to take the eleven liberated slaves to Detroit and then on a ferry to Canada. While passing through Chicago, Brown met with Allan Pinkerton who arranged and raised the fare for the passage to Detroit.[35] On March 12, 1859, Brown met with Frederick Douglass and Detroit abolitionists George DeBaptiste, William Lambert, and others at William Webb's house in Detroit to discuss emancipation.[36] DeBaptiste proposed that conspirators blow up some of the South's largest churches. The suggestion was opposed by Brown, who felt humanity precluded such unnecessary bloodshed.[37]

Over the course of the next few months, he traveled again through Ohio, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts to draw up more support for the cause. On May 9, he delivered a lecture in Concord, Massachusetts. In attendance were Bronson Alcott, Emerson and Thoreau. Brown reconnoitered with the Secret Six. In June he paid his last visit to his family in North Elba, before he departed for Harpers Ferry. He stayed one night en route in Hagerstown, Maryland at the Washington House, on West Washington Street. On June 30, 1859 the hotel had at least 25 guests, including I. Smith and Sons, Oliver Smith and Owen Smith and Jeremiah Anderson, all from New York. From papers found in the Kennedy Farmhouse after the raid, it is known that Brown wrote to Kagi that he would sign into a hotel as I. Smith and Sons.[38]

Raid

As he began recruiting supporters for an attack on slaveholders, Brown was joined by Harriet Tubman, "General Tubman," as he called her.[39] Her knowledge of support networks and resources in the border states of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware was invaluable to Brown and his planners. Although other abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison did not endorse his tactics, Brown dreamed of fighting to create a new state for freed slaves, and made preparations for military action. After he began the first battle, he believed, slaves would rise up and carry out a rebellion across the south.[40]

He asked Tubman to gather former slaves then living in present-day Southern Ontario who might be willing to join his fighting force, which she did.[41] Brown arrived in Harpers Ferry on July 3, 1859. A few days later, under the name Isaac Smith, he rented a farmhouse in nearby Maryland. He awaited the arrival of his recruits. They never materialized in the numbers he expected. In late August he met with Douglass in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he revealed the Harpers Ferry plan. Douglass expressed severe reservations, rebuffing Brown's pleas to join the mission. Douglass had actually known about Brown's plans from early in 1859 and had made a number of efforts to discourage blacks from enlisting.

In late September, the 950 pikes arrived from Charles Blair. Kagi's draft plan called for a brigade of 4,500 men, but Brown had only 21 men (16 white and 5 black: three free blacks, one freed slave, and a fugitive slave). They ranged in age from 21 to 49. Twelve had been with Brown in Kansas raids. On October 16, 1859, Brown (leaving three men behind as a rear guard) led 18 men in an attack on the Harpers Ferry Armory. He had received 200 Beecher's Bibles — breechloading .52 (13.2 mm) caliber Sharps rifles — and pikes from northern abolitionist societies in preparation for the raid. The armory was a large complex of buildings that contained 100,000 muskets and rifles, which Brown planned to seize and use to arm local slaves. They would then head south, drawing off more and more slaves from plantations, and fighting only in self-defense. As Frederick Douglass and Brown's family testified, his strategy was essentially to deplete Virginia of its slaves, causing the institution to collapse in one county after another, until the movement spread into the South, essentially wreaking havoc on the economic viability of the pro-slavery states.[citation needed]

Initially, the raid went well, and they met no resistance entering the town. They cut the telegraph wires and easily captured the armory, which was being defended by a single watchman. They next rounded up hostages from nearby farms, including Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington. They also spread the news to the local slaves that their liberation was at hand. Things started to go wrong when an eastbound Baltimore & Ohio train approached the town. The train's baggage master tried to warn the passengers. Brown's men yelled for him to halt and then opened fire. The baggage master, Hayward Shepherd, became the first casualty of Brown's war against slavery. Ironically, Shepherd was a free black man. Two of the hostages' slaves also died in the raid.[42] For some reason, after the shooting of Shepherd, Brown allowed the train to continue on its way.[citation needed]

A.J. Phelps, the Through Express passenger train conductor, sent a telegram to W.P. Smith, Master of Transportation of the B. & O. R. R., Baltimore:

Monocacy, 7.05 A. M., October 17, 1859.

Express train bound east, under my charge, was stopped this morning at Harper's Ferry by armed abolitionists. They have possession of the bridge and the arms and armory of the United States. Myself and Baggage Master have been fired at, and Hayward, the colored porter, is wounded very severely, being shot through the body, the ball entering the body below the left shoulder blade and coming out under the left side.[43]

News of the raid reached Baltimore early that morning and then on to Washington by late morning. In the meantime, local farmers, shopkeepers, and militia pinned down the raiders in the armory by firing from the heights behind the town. Some of the local men were shot by Brown's men. At noon, a company of militia seized the bridge, blocking the only escape route. Brown then moved his prisoners and remaining raiders into the engine house, a small brick building at the entrance to the armory. He had the doors and windows barred and loopholes were cut through the brick walls. The surrounding forces barraged the engine house, and the men inside fired back with occasional fury. Brown sent his son Watson and another supporter out under a white flag, but the angry crowd shot them. Intermittent shooting then broke out, and Brown's son Oliver was wounded. His son begged his father to kill him and end his suffering, but Brown said "If you must die, die like a man." A few minutes later, Oliver was dead. The exchanges lasted throughout the day.[citation needed]

By the morning of October 18 the engine house, later known as John Brown's Fort, was surrounded by a company of U.S. Marines under the command of First Lieutenant Israel Greene, USMC, with Colonel Robert E. Lee of the United States Army in overall command.[45] Army First Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart approached under a white flag and told the raiders that their lives would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused, saying, "No, I prefer to die here." Stuart then gave a signal. The Marines used sledge hammers and a makeshift battering-ram to break down the engine room door. Lieutenant Israel Greene cornered Brown and struck him several times, wounding his head. In three minutes Brown and the survivors were captives.[citation needed]

Altogether Brown's men killed four people, and wounded nine. Ten of Brown's men were killed (including his sons Watson and Oliver). Five of Brown's men escaped (including his son Owen), and seven were captured along with Brown. Among the raiders killed were John Henry Kagi; Lewis Sheridan Leary and Dangerfield Newby; those hanged besides Brown included John Anthony Copeland, Jr. and Shields Green.[46]

- Killed

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

- Hanged in 1859 following the raid

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

- Hanged in 1860

Albert Hazlett

Aaron D. Stevens

- Died during US Civil War

Barclay Coppock

Charles Plummer Tidd

- Survived

Osborne Perry Anderson

Owen Brown

Francis Jackson Meriam

- Freed

Former slave Isaac Gilbert, his wife, and their three children

Imprisonment and trial

Brown and the others captured were held in the office of the armory. On October 18, 1859, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, Virginia Senator James M. Mason, and Representative Clement Vallandigham of Ohio arrived in Harpers Ferry. Mason led the three-hour questioning session of Brown.

" [...] had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment. This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them." I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!"

--John Brown, in his speech following the conviction [47]

Although the attack had taken place on Federal property, Wise ordered that Brown and his men should be tried in Virginia in Charles Town, the nearby county seat capital of Jefferson County just seven miles west of Harpers Ferry (perhaps to avert Northern political pressure on the Federal government, or in the unlikely event of a presidential pardon). The trial began October 27, after a doctor pronounced the still-wounded Brown fit for trial. Brown was charged with murdering four whites and a black, with conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against Virginia. A series of lawyers were assigned to Brown, who included Lawson Botts, Thomas C. Green, Samuel Chilton, a lawyer from Washington D.C., and George Hoyt, but it was Hiram Griswold, a lawyer from Cleveland, Ohio, who concluded the defense on October 31. In his closing statement, Griswold argued that Brown could not be found guilty of treason against a state to which he owed no loyalty and of which he was not a resident, and that Brown had not personally killed anyone himself, and also that the failure of the raid indicated that Brown had not conspired with slaves. Andrew Hunter, the local district attorney, presented the closing arguments for the prosecution.

On November 2, after a week-long trial and 45 minutes of deliberation, the Charles Town jury found Brown guilty on all three counts. Brown was sentenced to be hanged in public on December 2. In response to the sentence, Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked that "[John Brown] will make the gallows glorious like the Cross." Cadets from the Virginia Military Institute under the leadership of General Francis H. Smith and Major Thomas J. Jackson (who would earn the nickname "Stonewall" less than two years later) were called into service as a security detail in the event Brown's supporters attempted a rescue.

During his month in jail, Brown was allowed to send and receive correspondence. One of the letters was from Mahala Doyle, wife and mother of three of Brown's Kansas victims. She wrote "Altho' vengeance is not mine, I confess that I do feel gratified to hear that you were stopped in your fiendish career at Harper's Ferry ..." In a postscript she added "My son John Doyle whose life I beg[g]ed of you is now grown up and is very desirous to be in Charlestown on the day of your execution."[48]

Brown refused to be rescued by Silas Soule, a friend from Kansas who had somehow infiltrated the Jefferson County Jail offering to break him out during the night and flee northward. Brown supposedly told Silas that, aged 59, he was too old to live a life on the run from the federal authorities and was ready to die as a martyr. Silas left him behind to be executed. More importantly, many of Brown's letters exuded high tones of spirituality and conviction and, when picked up by the northern press, won increasing numbers of supporters in the North as they simultaneously infuriated many white people in the South. On December 1, his wife arrived by train in Charles Town where she joined him at the county jail for his last meal. She was denied permission to stay for the night, prompting Brown to lose his composure for the only time through the ordeal.

Victor Hugo's reaction

Victor Hugo, from exile on Guernsey, tried to obtain pardon for John Brown: he sent an open letter that was published by the press on both sides of the Atlantic (cf. Actes et paroles). This text, written at Hauteville-House on December 2, 1859, warned of a possible civil war:

[...] Politically speaking, the murder of John Brown would be an uncorrectable sin. It would create in the Union a latent fissure that would in the long run dislocate it. Brown's agony might perhaps consolidate slavery in Virginia, but it would certainly shake the whole American democracy. You save your shame, but you kill your glory. Morally speaking, it seems a part of the human light would put itself out, that the very notion of justice and injustice would hide itself in darkness, on that day where one would see the assassination of Emancipation by Liberty itself. [...]

Let America know and ponder on this: there is something more frightening than Cain killing Abel, and that is Washington killing Spartacus.

Death and aftermath

On the morning of December 2, 1859, Brown wrote:

"I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done."[49]

He read his Bible and wrote a final letter to his wife, which included his will. At 11:00 a.m. he was escorted from the county jail through a crowd of 2,000 soldiers a few blocks away to a small field where the gallows were. Among the soldiers in the crowd were future Confederate general Stonewall Jackson and John Wilkes Booth, who borrowed a militia uniform to gain admission to the execution.[50] The poet Walt Whitman, in Year of Meteors, described viewing the execution.[51]

Brown was accompanied by the sheriff and his assistants, but no minister since he had consistently rejected the ministrations of pro-slavery clergy. Since the region was in the grips of virtual hysteria, most northerners, including journalists, were run out of town, and it is unlikely any anti-slavery clergyman would have been safe, even if one were to have sought to visit Brown. He elected to receive no religious services in the jail or at the scaffold. He was hanged at 11:15 am and pronounced dead at 11:50 am. His body was placed in a wooden coffin with the noose still around his neck. His coffin was then put on a train to take it away from Virginia to his family homestead in New York for burial. In the North, large memorial meetings took place, church bells rang, minute guns were fired, and famous writers such as Emerson and Thoreau joined many Northerners in praising Brown.[52]

Senate investigation

On December 14, 1859, the U.S. Senate appointed a bipartisan committee to investigate the Harpers Ferry raid and to determine whether any citizens contributed arms, ammunition or money to John Brown's men. The Democrats attempted to implicate the Republicans in the raid; the Republicans tried to disassociate themselves from Brown and his acts.

The Senate committee heard testimony from 32 witnesses, including Liam Dodson, one of the surviving abolitionists. The report, authored by chairman James M. Mason, a pro-slavery politician from Virginia, was published in June, 1860. It found no direct evidence of a conspiracy, but implied that the raid was a result of Republican doctrines.[53] The two committee Republicans published a minority report, but were apparently more concerned about denying Northern culpability than clarifying the nature of Brown's efforts. Republicans such as Abraham Lincoln rejected any connection with the raid. Lincoln called Brown "insane".[54]

The investigation was performed in a tense environment in both houses of Congress. One senator wrote to his wife that "The members on both sides are mostly armed with deadly weapons and it is said that the friends of each are armed in the galleries." After a heated exchange of insults, a Mississippian attacked Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania with a Bowie knife in the House of Representatives. Stevens' friends prevented a fight.[55]

The Senate committee was very cautious in its questions of two of Brown's backers, Samuel Howe and George Stearns, out of fear of stoking violence. Howe and Stearns later said that the questions were asked in a manner that permitted them to give honest answers without implicating themselves.[56] Civil War historian James M. McPherson stated that "A historian reading their testimony, however, will be convinced that they told several falsehoods."[57]

Aftermath of the raid

The raid on Harpers Ferry is generally thought to have done much to set the nation on a course toward civil war.[58] Southern slaveowners, hearing initial reports that hundreds of abolitionists were involved, were relieved the effort was so small. Yet they feared other abolitionists would emulate Brown and attempt to lead slave rebellions.[59] Therefore, the South reorganized the decrepit militia system. These militias, well-established by 1861, became a ready-made Confederate army, making the South better prepared for war.[60]

Southern Democrats charged that Brown's raid was an inevitable consequence of the Republican Party's political platform, which they associated with abolition. In light of the upcoming elections in November 1860, the Republican political and editorial response to John Brown tried to distance themselves as much as possible from Brown, condemning the raid and dismissing Brown as an insane fanatic. As one historian explains, Brown was successful in polarizing politics:

Brown's raid succeeded brilliantly. It drove a wedge through the already tentative and fragile Opposition-Republican coalition and helped to intensify the sectional polarization that soon tore the Democratic party and the Union apart.[60]

Many abolitionists in the North viewed Brown as a martyr, sacrificed for the sins of the nation. Immediately after the raid, William Lloyd Garrison published a column in The Liberator, judging Brown's raid as "well-intended but sadly misguided" and "an enterprise so wild and futile as this".[61] However, he defended Brown's character from detractors in the Northern and Southern press, and argued that those who supported the principles of the American Revolution could not consistently oppose Brown's raid. (Garrison reiterated the point, adding that "whenever commenced, I cannot but wish success to all slave insurrections", in a speech in Boston on the day Brown was hanged.)[62][63]

After the Civil War, Black leader Frederick Douglass wrote, "His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine—it was as the burning sun to my taper light—mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him."[64]

Viewpoints of historians

As the United States distanced itself from the cause of slavery and "bayonet rule" in the South, the historical view of Brown declined in a manner parallel with the demise of Reconstruction. In the 1880s, Brown's detractors – some of them contemporaries embarrassed by their fervent abolitionism – began to produce virulent exposés, particularly emphasizing the Pottawatomie killings of 1856.

Although Oswald Garrison Villard's 1910 biography of Brown was thought to be friendly, Villard being the grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, he also added fuel to the anti-Brown fire by criticizing him as a muddled, pugnacious, bumbling, and homicidal madman.[66][67] Villard himself was a pacifist and admired Brown in many respects, but his interpretation of the facts provided a paradigm for later anti-Brown writers. By the mid-20th century, some scholars were fairly convinced that John Brown was a fanatic and killer, while some African Americans sustained a positive view of the man.[68][69]

Recent biographers' accounts vary, although several works that have been published on Brown since the opening of the 21st century have marked a significant shift away from the hostility of writers on Brown. Toledo (2002), Peterson (2002), DeCaro (2002, 2007), Reynolds (2005), and Carton (2006) are critically appreciative of Brown's history, far from the opinions of earlier writers. A division of opinion is evident in two recent works of historical fiction: Bruce Olds's 1995 Raising Holy Hell, which portrays Brown as a religious zealot tortured by delusions of godly violence; and the more unapologetically sympathetic fictional portrayal of Brown found in Russell Banks's 1998 Cloudsplitter. The shift to an appreciative perspective on Brown moves many white historians toward the view long held by black scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Benjamin Quarles, and Lerone Bennett, Jr.[citation needed]

Writing in the 1970s, Albert Fried, a biographer and historiographer of Brown, concluded that historians who portrayed Brown as a dysfunctional figure are "really informing me of their predilections, their judgment of the historical event, their identification with the moderates and opposition to the 'extremists.'"[70] It is this less studied, highly interpretive view of Brown that has prevailed in academic writing as well as in journalism; as biographer Louis DeCaro Jr. has recently written, "there is no consensus of fairness with respect to Brown in either the academy or the media."[71] The portrayal by some writers of Brown as another Timothy McVeigh or Osama bin Laden[72][73] may still reflect the same bias that Fried discussed a generation ago. DeCaro likewise complains of writers taking "unstudied liberties" and concludes that in the 20th century alone, "poisonous portrayals [of Brown were] so prevalent as virtually to have formed one long screed of hyperbole and sarcasm in the name of historical narrative."[74]

- Some historians, such as Paul Finkelman, compare him to contemporary terrorists such as Osama bin Laden and Timothy McVeigh.[75]

- Historian James Gilbert labels John Brown a terrorist in terms of twenty-first century criteria and psychological profiles of terrorists.[76]

- Biographer Stephen B. Oates has described him as "maligned as a demented dreamer... (but) in fact one of the most perceptive human beings of his generation";[77]

- Biographer David S. Reynolds gives Brown credit for starting the civil war or "killing slavery", and cautions others against identifying Brown with terrorism.[78] Reynolds sees him as the inspiration for the Civil Rights Movement a century later, arguing "it is misleading to identify Brown with modern terrorists."[79]

- Historian and Brown researcher Paul Finkelman calls him "simply part of a very violent world" and states that Brown "is a bad tactician, a bad strategist, he's a bad planner, he's not a very good general – but he's not crazy"[80]

- Biographer Louis A. DeCaro Jr., who has debunked many historical allegations about Brown's early life and public career, concludes that although he "was hardly the only abolitionist to equate slavery with sin, his struggle against slavery was far more personal and religious than it was for many abolitionists, just as his respect and affection for black people was far more personal and religious than it was for most enemies of slavery."[81]

- Historian and Brown documentary scholar Louis Ruchames wrote: "Brown's action was one of great idealism and placed him in the company of the great liberators of mankind.";[82]

- Biographer Otto Scott introduces his work on Brown by writing: "In the late 1850s a new type of political assassin appeared in the United States. He did not murder the mighty – but the obscure. ... his purposes were the same as those of his classic predecessors: to force the nation into a new political pattern by creating terror."[83]

- Criminologist James N. Gilbert writes: "Brown's deeds conform to contemporary definitions of terrorism, and his psychological predispositions are consistent with the terrorist model."[84]

- Journalist and documentary writer Ken Chowder writes that Brown was "stubborn ... egoistical, self-righteous, and sometimes deceitful; yet ... at certain times, a great man". Chowder argues that Brown has been adopted by both left and right wing, and his actions "spun" to fit the world view of the spinner at various times in American history."[80] Chowder has also called Brown "the father of American terrorism".[85]

- Malcolm X said that white people could not join his black nationalist Organization of Afro-American Unity, but "if John Brown were still alive, we might accept him."[86]

- Lawyer Brian Harris writes: "Whatever view you take of the consequences of Harpers Ferry, and for all that it was a botched job which resulted in the unnecessary deaths of innocents, it had at least the merit of having been undertaken for the noblest of motives. The same cannot be said for the sadistic butchery that was Pottawatomie. It served no useful purpose other than to vent an old man's rage, and Brown is the smaller for it."[87]

- Director Quentin Tarantino said: "My favorite hero in American history is John Brown. ... He basically single-handedly started the road to end slavery and the fact that he killed people to do it. He decided, 'If we start spilling white blood, then they're going to start getting the idea.'"[88]

Visual portrayals

The two most noted screen portrayals of Brown have both been given by actor Raymond Massey. The 1940 film Santa Fe Trail, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, depicted Brown completely unsympathetically as an out-and-out villainous madman, and Massey added to that impression by playing him with a constant, wild-eyed stare. The film gave the impression that it did not oppose African-American slavery, even to the point of having a black "mammy" character say, after an especially fierce battle, "Mr. Brown done promised us freedom, but... if this is freedom, I don't want no part of it". Massey portrayed Brown again in the little-known, low-budget Seven Angry Men, in which he was not only unquestionably the main character, but was depicted and acted in a much more restrained, sympathetic way.[89]

Massey along with Tyrone Power and Judith Anderson starred in the acclaimed 1953 dramatic reading of Stephen Vincent Benet's epic poem John Brown's Body Three actors in formal dress recited and acted in a two-hour presentation of the poem. The production toured sixty cities in twenty-eight states.[90] In Book I of his epic poem, Benet called him a stone, "to batter into bits an actual wall and change the actual scheme of things."

Brown was also portrayed on film by John Cromwell in the 1940 Abe Lincoln in Illinois. Cromwell was the director of the film and was not credited in the role. Lincoln was played by Raymond Massey.

Singer Johnny Cash portrayed a noble but unrealistic John Brown in Book I, Episode Five of the 1985 TV miniseries North and South.[91]

Royal Dano portrayed John Brown in the 1971 western comedy Skin Game.

Sterling Hayden also portrayed John Brown in the 1982 miniseries The Blue and the Gray.

In 1938–1940, American painter John Steuart Curry created Tragic Prelude, a mural of John Brown holding a gun and a Bible, in the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka, Kansas. In 1941, Jacob Lawrence illustrated the life of John Brown in The Legend of John Brown, a series of twenty-two gouache paintings. By 1977, the original paintings were in such fragile condition they could not be displayed, and the Detroit Institute of Arts commissioned Lawrence to recreate the series as a portfolio of silkscreen prints. The result was a limited edition portfolio of twenty-two hand-screened prints. The works were printed and published with a poem, John Brown, by Robert Hayden, which was commissioned specifically for the project. Though John Brown had been a popular topic for many painters, The Legend of John Brown was the first to explore the topic from an African American perspective.[92]

The progressive rock band Kansas adapted Curry's painting of John Brown as the cover of their first album, Kansas, released in 1974. A similar image of Brown appears on The Best of Kansas, along with images referencing other previous Kansas albums.

Paintings such as Hovenden's The Last Moments of John Brown immortalize an apocryphal story, in which a Black woman offers the condemned Brown her baby to kiss on his way to the gallows. It was probably a tale invented by journalist James Redpath.[93]

Influences

The connection between John Brown's life and many of the slave uprisings in the Caribbean was clear from the outset. Brown was born during the period of the Haitian Revolution, which saw Haitian slaves revolting against the French. The role the revolution played in helping to formulate Brown's abolitionist views directly is not clear; however, the revolution had an obvious effect on the general view towards slavery in the northern United States. As W.E.B. Du Bois notes, the involvement of slaves in the American Revolutions, as well as the "upheaval in Hayti, and the new enthusiasm for human rights, led to a wave of emancipation which started in Vermont... swept through New England and Pennsylvania, ending finally in New York and New Jersey."[94] This changed sentiment, which occurred during the late 18th and early 19th century, undoubtedly had a role in creating Brown's abolitionist opinion, during his upbringing.

The 1839 slave insurrection aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad, off the coast of Cuba, provides a poignant example of John Brown's support and appeal towards Caribbean slave revolts. On La Amistad, Joseph Cinqué and approximately 50 other slaves captured the ship, slated to transport them from Havana to Puerto Principe, Cuba in July 1839, and attempted to return to Africa. However, through trickery, the ship ended up in the United States, where Cinque and his men stood trial. Ultimately, the courts acquitted the men because at the time the international slave trade was illegal in the United States.[95] According to Brown's daughter, "Turner and Cinque stood first in esteem" among Brown's black heroes. Furthermore, she noted Brown's "admiration of Cinques' character and management in carrying his points with so little bloodshed!"[96] In 1850, Brown would refer affectionately to the revolt, in saying "Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery. Witness the case of Cinques, of everlasting memory, on board the 'Amistad.'"[97] The slave revolts of the Caribbean had a clear and important impact on Brown's views toward slavery and his staunch support of the most severe forms of abolitionism. However, this is not the most important part of the many revolts' legacy of influencing Brown.

The specific knowledge John Brown gained from the tactics employed in the Haitian Revolution, and other Caribbean revolts, was of paramount importance when Brown turned his sights to the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. As Brown's cohort Richard Realf explained to a committee of the 36th Congress, "he had posted himself in relation to the wars of Toussaint L'Ouverture... he had become thoroughly acquainted with the wars in Hayti and the islands round about."[98] By studying the slave revolts of the Caribbean region, Brown learned a great deal about how to properly conduct guerilla warfare. A key element to the prolonged success of this warfare was the establishment of Maroon communities, which are essentially colonies of runaway slaves. As a contemporary article notes, Brown would use these establishments to "retreat from and evade attacks he could not overcome. He would maintain and prolong a guerilla war, of which... Haiti afforded" an example.[99]

The idea of creating Maroon communities was the impetus for the creation of John Brown's "Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States," which helped to detail how such communities would be governed. However, the idea of Maroon colonies of slaves is not an idea exclusive to the Caribbean region. In fact, Maroon communities riddled the southern United States between the mid-1600s and 1864, especially the Great Dismal Swamp region of Virginia and North Carolina. Similar to the Haitian Revolution, the Seminole Wars, fought in modern-day Florida, saw the involvement of Maroon communities, which although outnumbered by native allies were more effective fighters.[99]

Although the Maroon colonies of North America undoubtedly had an effect on John Brown's plan, their impact paled in comparison to that of the Maroon communities in places like Haiti, Jamaica and Surinam. Accounts by Brown's friends and cohorts prove this idea. Richard Realf, a cohort of Brown in Kansas, noted that Brown not only studied the slave revolts in the Caribbean, but focused more specifically on the maroons of Jamaica and those involved in Haiti's liberation.[100] Brown's friend Richard Hinton similarly noted that Brown knew "by heart," the occurrences in Jamaica and Haiti.[101] Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a cohort of Brown's and a member of the Secret Six, stated that Brown's plan involved getting "together bands and families of fugitive slaves" and "establish them permanently in those [mountain] fastnesses, like the Maroons of Jamaica and Surinam."[102] Brown had planned for the Maroon colonies established to be "durable," and thus able to endure over a prolonged period of war.

The similarities between John Brown's attempted insurrection and the Haitian Revolution, in both methods, motivations and resolve, is still seen today as the main avenue in Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince is still named for Brown as a sign of solidarity.[103]

Cultural references

- In the 1921 dramatic monologue "John Brown" by Edwin Arlington Robinson, Brown speaks to his wife on the night before his execution.

- Marching Song (1932) is an unpublished play about the legend of John Brown written by Orson Welles.[104]: 222–226

- The 1940 film Santa Fe Trail portrays Brown as a madman whom the federal army must stop. The climax is the battle at Harper's Ferry.

- Henry Miller's Plexus (Book Two of The Rosy Crucifixion) (1953) discusses John Brown.

- In Langston Hughes's Selected Poems (1958), on page 10 is a poem called October 16. In the poem Hughes celebrates John Brown's actions.

- The 1994 novel, Flashman and the Angel of the Lord, by George MacDonald Fraser. The central character, Harry Paget Flashman becomes involved in the Harpers Ferry Raid; the novel includes both a description of the raid and a study of the character of John Brown.

- The 1998 biographical novel about John Brown, Cloudsplitter, by Russell Banks was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. It is narrated from the point of view of Brown's surviving son, Owen.[105]

- The 2000 song "Meteor Of War", from Rancid, by the punk rock band Rancid has John Brown and his actions as its topic.

- The 2006 video game Splinter Cell: Double Agent features a fictional terrorist group known as John Browns Army (JBA), created in the name of John Brown and his visions.

- In 2007, University of Kansas football fans mocked their historic rivals at the University of Missouri during the run-up to that year's football game between the two by sporting T-shirts featuring an image of Brown and the caption "Kansas: Keeping America Safe From Missouri Since 1854."[106]

- James McBride's 2013 novel The Good Lord Bird tells John Brown's story through the eyes of a young slave, Henry Shackleford, who accompanies Brown to Harper's Ferry. The novel won the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction.[107]

Citations

- ^ There has been speculation that the grandfather was the same John Brown who was a Loyalist during the American Revolution and spent time in jail with the notorious Claudius Smith (1736–1779), allegedly for stealing cattle, which he and Smith used to feed starving British troops. However, this runs against the grain of the Brown family history as well as the record of the Humphrey family, to which the Browns were directly related (abolitionist John Brown's maternal grandmother was a Humphrey). Brown himself wrote in his 1857 autobiographical letter that both his and his first wife's grandfather were soldiers in the Continental Army [which he established in his, The Humphreys Family in ' (1883)], which notes that abolitionist John Brown's grandfather, Capt. John Brown (born November 4, 1728), was a militia captain who died early in the American Revolution. His son, Owen Brown, the father of abolitionist John Brown, was a tanner and strict evangelical who hated slavery and taught his trade to his son.

- ^ Franklin Sanborn. "John Brown in Massachusetts", The Atlantic, April 1872.

- ^ Ulysses S Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, (The Library of America, 1990) ISBN 978-0-940450-58-5

- ^ John Brown profile, pabook.libraries.psu.edu; accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Cowan, Wes (December 6, 2007). "Cowan's Auctions". Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Blackmar, Frank Wilson (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc. Standard Publishing Company. p. 244.

- ^ Caccamo, James F. (2007). "John Brown: A Brief Chronology". Historical Archives. Hudson Library & Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 20, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ Eric Foner (2006). Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 9780375702747.

- ^ a b c d e Massachusetts. "Abolitionist John Brown's years in Springfield Ma. transform his anti-slavery thoughts and actions". masslive.com. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "John Brown in Massachusetts – 1872.04". Theatlantic.com. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Springfield, MA – Our Plural History". Ourpluralhistory.stcc.edu. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "History | St. John's Congregational Church | Springfield, MA". Sjkb.org. June 22, 2010. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "John Brown: In His Own Words – Prelude". Zikibay.com. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Abolitionism". GHS IB History of the Americas. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reynolds, David S. (2009). John Brown, Abolitionist. New York: Random House Digital Inc. p. 124.

- ^ "A history of the Adirondacks". Archive.org. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "John Brown Farm, North Elba, New York". New York History Net.

- ^ Rhodes, James Fork (1892). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. Original from Harvard University: Harper & Brothers. p. 385.

- ^ Robinson, Charles. The Kansas Conflict. 1892. Reprint. Lawrence, Kans.: Journal Publishing Co., 1898.

- ^ Watts, Dale E. "How Bloody Was Bleeding Kansas?", Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains18 (2) (Summer 1995): pp. 116–29.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Vintage Books. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-375-72615-6.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 200–01. ISBN 978-0-375-72615-6.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 201–02. ISBN 978-0-375-72615-6.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 203–04. ISBN 978-0-375-72615-6.

- ^ Irving Berdine Richman. John Brown Among the Quakers: And Other Sketches, page 12.

- ^ Richard Josiah Hinton. John Brown and his men: with some account of the roads they traveled to reach Harper's Ferry, p. 118.

- ^ Hiram Alvin Reid. History of Pasadena: Comprising an Account of the Native Indian, the Early Spanish, the Mexican, the American, the Colony, and the Incorporated City, Occupancies of the Rancho San Pasqual, and Its Adjacent Mountains, Canyons, Waterfalls and Other Objects of ... Interest: Being a Complete and Comprehensive Histo-cyclopedia of All Matters Pertaining to this Region, p. 325

- ^ Memoirs of John Brown: Written for Rev. Samuel Orcutt's History of ... – Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, William Ellery Channing – Google Books. Books.google.com. 1878. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ Jason Emerson "The Secret Six," American Heritage, Fall 2009.

- ^ Jones, Louis Thomas (1914). The Quakers of Iowa. Iowa City: The State Historical Society of Iowa. p. 193: "A little over a year after his first visit to the Springdale neighborhood, Brown reappeared late in December, 1857—this time with some ten companions and for purposes which he seemed not anxious to have known. The men were lodged with a Quaker, William Maxon, about three miles northeast of the village of Springdale, Brown agreeing to give in exchange for their keep such of his teams or wagons as might seem just and fair. Brown himself was taken into the home of John H. Painter, about a half-mile away; and all were welcomed with that unfeigned hospitality for which the Friends have always been known.

- ^ Morel, Lucas E. "In Pursuit of Freedom." Teachinghistory.org; retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "John Brown's Convention 1858". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Chatham Convention Delegates". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ The History of Johnson County, Iowa, 1883, pp. 475–77

- ^ Underground Railroad, US Department of Interior, National Park Service, Denver Service Center. DIANE Publishing, Feb 1, 1995, p168

- ^ Toledo, Gregory. The Hanging of Old Brown: A Story of Slaves, Statesmen, and Redemption. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. p75

- ^ John Brown in Washington County, whilbr.org; accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Clinton, p. 129.

- ^ Clinton, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Larson, p. 159.

- ^ John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid, wvculture.org; accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Senate of Maryland, 1860, Correspondence relating to the Insurrection at Harper's Ferry, October 17, 1859 The Insurrection at Harper's Ferry, whilbr.org, October 17, 1859.

- ^ Both Coppock photos from A topical history of Cedar County, Iowa, Volume 1 (1910) Clarence Ray Aurner, S.J. Clarke Publishing Company

- ^ Hoffman, Colonel Jon T., USMC: A Complete History, Marine Corps Association, Quantico, VA, (2002), p. 84.

- ^ "John Brown: The Conspirators". virginia.edu. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "John Brown's Last Speech". www.historyisaweapon.com.

- ^ Oates (1984) pp. 344–45

- ^ Territorial Kansas Online: John Brown (1800–1859), territorialkansasonline.org; accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Evan Carton, Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America (2006), pp. 332–333.

- ^ Walt Whitman Archive: "Year of Meteors"; retrieved March 13, 2011

- ^ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 378–79

- ^ "Senate Select Committee Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. June 15, 1860. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ David Donald, Lincoln (1995) p. 239

- ^ Oates (1984), p. 359

- ^ Oates (1984), pp. 359–60

- ^ James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press (1988), pp. 207.

- ^ David Potter, The Impending Crisis, pp. 356–84.

- ^ David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005) p. 6

- ^ a b Daniel W. Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989), pp. 70 ff.

- ^ "The Tragedy at Harper's Ferry", fair-use.org; accessed November 12, 2015.

- ^ See opposed any use of violence on principle

- ^ John Brown and the Principle of Nonresistance December 16, 1859

- ^ Frederick Douglass, John Brown. An Address at the Fourteenth Anniversary of Storer College, May 30, 1881; online at Project Gutenberg, gutenberg.org; accessed November 12, 2015.

- ^ For more information, see John Brown Statue and Memorial Plaza.

- ^ Ken Chowder, Archived 2006-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frederick J. Blue in American Historical Review (April 2006) v. 111, pp. 481–82.

- ^ Louis A. DeCaro Jr., "Black People's Ally, White People's Bogeyman: A John Brown Story" in Andrew Taylor and Eldrid Herrington (editors), The Afterlife of John Brown (New York: Palgrave/Macmillan, 2005), pp. 11–26.

- ^ David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005); Stephen Oates quoted at [1]

- ^ Albert Fried, John Brown's Journey: Notes & Reflections on His America & Mine (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor/Doubleday, 1978), p. 272.

- ^ Louis A. DeCaro Jr., John Brown – The Cost of Freedom: Selections from His Life & Letters (New York: International Publishers, 2007), p. 16.

- ^ Ken Chowder, "The Father of American Terrorism", American Heritage (February 2000) vol. 51#1 pp. 81–91 Archived 2006-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Spring 2011). "John Brown: America's First Terrorist?". Prologue. 43 (1). The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration: 16–27.

says "no"

- ^ DeCaro, John Brown – The Cost of Freedom, pp. 16, 17.

- ^ R. Blakeslee Gilpin (2011). John Brown Still Lives!: America's Long Reckoning With Violence, Equality, & Change. U. of North Carolina Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780807869277.