Latin script

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2017) |

| Latin Roman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | ~700 BC–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages |

|

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | indirectly, the Cherokee syllabary and Yugtun script |

Sister systems | Cyrillic Armenian Georgian Coptic Runic/Futhark |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Latin |

| See Latin characters in Unicode | |

Latin or Roman script is a set of graphic signs (script) based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet. This is derived from a form of the Cumaean Greek version of the Greek alphabet used by the Etruscans.

Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation, and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the basis of the International Phonetic Alphabet, and the 26 most widespread letters are the letters contained in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

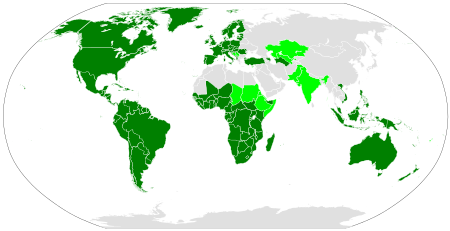

Latin script is the basis for the largest number of alphabets of any writing system[1] and is the most widely adopted writing system in the world (commonly used by about 70% of the world's population). Latin script is used as the standard method of writing in most Western, Central, as well as in some Eastern European languages, as well as in many languages in other parts of the world.

Name

The script is either called Roman script or Latin script, in reference to its origin in ancient Rome. In the context of transliteration, the term "romanization" or "romanisation" is often found.[2][3] Unicode uses the term "Latin"[4] as does the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[5]

The numeral system is called the Roman numeral system; and the collection of the elements, Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2, 3 ... are Latin/Roman script numbers for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

History

Old Italic alphabet

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | A | B | C | D | E | V | Z | H | Θ | I | K | L | M | N | Ξ | O | P | Ś | Q | R | S | T | Y | X | Φ | Ψ | F |

Archaic Latin alphabet

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | A | B | C | D | E | F | Z | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small vertical stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek letters ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraɪka | ˈdzeːta |

ISO basic Latin alphabet

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the sound [w] found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the runic Wynn letter which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

Spread

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

Middle Ages

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language uses both scripts, with Cyrillic predominating in official communication and Latin elsewhere, as determined by the Law on Official Use of the Language and Alphabet.[6]

Since the 16th century

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Through European colonization the Latin script has spread to the Americas, Oceania, parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, in forms based on the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, German and Dutch alphabets.

It is used for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah; however, the sound values are completely different.[citation needed]

Since 19th century

In the late 19th century, the Romanians returned to the Latin alphabet, which they had used until the Council of Florence in 1439,[7] primarily because Romanian is a Romance language. The Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and their Church, increasingly influenced by Russia after the fall of Byzantine Greek Constantinople in 1453 and capture of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic.

Under French rule and Portuguese missionary influence, a Latin alphabet was devised for the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters.

Since 20th century

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted a Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, used the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three of the newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages.

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia. In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although the only official Kurdish government uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish-speakers.

In 2015, the Kazakh government announced that the Latin alphabet would replace Cyrillic as the writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[8]

International standards

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage.

As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

As used by various languages

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore created, be it by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining an alphabetical order or collation sequence, which can vary with the particular language.

Letters

Some examples of new letters to the standard Latin alphabet are the Runic letters wynn ⟨Ƿ/ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨Þ/þ⟩, and the letter eth ⟨Ð/ð⟩, which were added to the alphabet of Old English. Another Irish letter, the insular g, developed into yogh ⟨Ȝ/ȝ⟩, used in Middle English. Wynn was later replaced with the new letter ⟨w⟩, eth and thorn with ⟨th⟩, and yogh with ⟨gh⟩. Although the four are no longer part of the English or Irish alphabets, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic and Faroese alphabets.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters that have a similar sound value to their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Adangme uses the letters ⟨Ɛ/ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ/ɔ⟩, and Ga uses ⟨Ɛ/ɛ⟩, ⟨Ŋ/ŋ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ/ɔ⟩. Hausa uses ⟨Ɓ/ɓ⟩ and ⟨Ɗ/ɗ⟩ for implosives, and ⟨Ƙ/ƙ⟩ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

The Azerbaijani language also has the letter written as "Ə", which represents the near-open front unrounded vowel.

Multigraphs

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. Examples are ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩, ⟨rh⟩, ⟨sh⟩ in English, and ⟨ij⟩ in Dutch. In Dutch the ⟨ij⟩ is capitalized as ⟨IJ⟩ or the ligature ⟨IJ⟩, but never as ⟨Ij⟩, and it often takes the appearance of a ligature ⟨ij⟩ very similar to the letter ⟨ÿ⟩ in handwriting.

A trigraph is made up of three letters, like the German ⟨sch⟩, the Breton ⟨c'h⟩ or the Milanese ⟨oeu⟩. In the orthographies of some languages, digraphs and trigraphs are regarded as independent letters of the alphabet in their own right. The capitalization of digraphs and trigraphs is language-dependent, as only the first letter may be capitalized, or all component letters simultaneously (even for words written in titlecase, where letters after the digraph or trigraph are left in lowercase).

Ligatures

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph or character. Examples are ⟨Æ/æ⟩ (from ⟨AE⟩, called "ash"), ⟨Œ/œ⟩ (from ⟨OE⟩, sometimes called "oethel"), the abbreviation ⟨&⟩ (from Latin et "and"), and the German symbol ⟨ß⟩ ("sharp S" or "eszet", from ⟨ſz⟩ or ⟨ſs⟩, the archaic medial form of ⟨s⟩, followed by a ⟨z⟩ or ⟨s⟩).

Diacritics

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent, is a small symbol that can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut sign used in the German characters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ or the Romanian characters ă, â, î, ș, ț. Its main function is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also modify the pronunciation of a whole syllable or word, or distinguish between homographs. As with letters, the value of diacritics is language-dependent. English and Dutch are the only major modern European languages requiring no diacritics for native words (although a diaeresis may be used in words such as "coöperation").[9][10]

Collation

Some modified letters, such as the symbols ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩, may be regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based, as is done in Swedish. In other cases, such as with ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ in German, this is not done; letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs and trigraphs. Different diacritics may be treated differently in collation within a single language. For example, in Spanish, the character ⟨ñ⟩ is considered a letter, and sorted between ⟨n⟩ and ⟨o⟩ in dictionaries, but the accented vowels ⟨á⟩, ⟨é⟩, ⟨í⟩, ⟨ó⟩, ⟨ú⟩ are not separated from the unaccented vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩.

Capitalization

The languages that use the Latin script today generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalized, in the same way that Modern German is written today, e.g. Alle Schwestern der alten Stadt hatten die Vögel gesehen ("All of the sisters of the old city had seen the birds").

Romanization

Words from languages natively written with other scripts, such as Arabic or Chinese, are usually transliterated or transcribed when embedded in Latin-script text or in multilingual international communication, a process termed Romanization.

Whilst the Romanization of such languages is used mostly at unofficial levels, it has been especially prominent in computer messaging where only the limited 7-bit ASCII code is available on older systems. However, with the introduction of Unicode, Romanization is now becoming less necessary. Note that keyboards used to enter such text may still restrict users to Romanized text, as only ASCII or Latin-alphabet characters may be available.

See also

- Romic alphabet

- List of languages by writing system#Latin script

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

- Latin letters used in mathematics

Notes

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96

- ^ "Search results | BSI Group". Bsigroup.com. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ^ "Romanisation_systems". Pcgn.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ^ "ISO 15924 – Code List in English". Unicode.org. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ^ "Search – ISO". Iso.org. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ^ "ZAKON O SLUŽBENOJ UPOTREBI JEZIKA I PISAMA" (PDF). Ombudsman.rs. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Descriptio_Moldaviae". La.wikisource.org. 1714. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ^ Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 2015-09-28.

- ^ As an example, an article containing a diaeresis in "coöperate" and a cedilla in "façades" as well as a circumflex in the word "crêpe" (Grafton, Anthony (2006-10-23). "Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma". The New Yorker.)

- ^ "The New Yorker's odd mark — the diaeresis"

References

- Haarmann, Harald (2004), Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.), München: C. H. Beck, ISBN 3-406-47998-7

Further reading

- Boyle, Leonard E. 1976. "Optimist and recensionist: 'Common errors' or 'common variations.'" In Latin script and letters A.D. 400–900: Festschrift presented to Ludwig Bieler on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Edited by John J. O’Meara and Bernd Naumann, 264–74. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Morison, Stanley. 1972. Politics and script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. Oxford: Clarendon.