Lemkos

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Polish. (December 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 672[1] | |

| 11,000 (census, 2011)[2] | |

| 55,469[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Rusyn language, Ukrainian language, Polish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Ukrainian Greek Catholic or Orthodox, with Roman Catholic minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Boykos, Hutsuls | |

- This article refers to the Lemko peoples. For their attempted nation, please see Lemko Republic.

Lemkos (Template:Lang-uk, Template:Lang-pl, Lemko: Лeмкы, translit. Lemky; sing. Лeмкo, Lemko) are one of several quantitatively and territorially small ethnic sub-groups inhabiting a stretch of the Carpathian Mountains known as Lemkivshchyna. Many Lemkos identify as a branch of Ukrainians.

Their spoken language, which is uncodified, has been variously described as a language in its own right,[citation needed] a dialect of Rusyn, or a dialect of the Ukrainian language. In Ukraine almost all Lemkos also speak Ukrainian, according to the 2001 Ukrainian Census.[4]

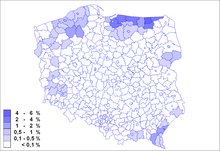

In the Polish Census of 2011, 11,000 people declared Lemko nationality, of whom 6,000 declared only Lemko nationality, 4,000 declared double national identity – Lemko-Polish, and 1,000 declared Lemko identity together with non-Polish identity.[2]

Location

| Part of a series on |

| Ukrainians |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Languages and dialects |

| Religion |

| Sub-national groups |

| Closely-related peoples |

The Lemkos' homeland is commonly referred to as Lemkivshchyna (Template:Lang-uk, Lemko: Lemkovyna (Лeмкoвина), Template:Lang-pl). Up until 1945, this included the area from the Poprad River in the west to the valley of Oslawa River in the east, areas situated primarily in present-day Poland, in the Lesser Poland and Subcarpathian Voivodeships (provinces). This part of the Carpathian mountains is mostly deforested, which allowed for an agrarian economy, alongside such traditional occupations as ox grazing and sheep herding.

The Lemko region became part of Poland in medieval Piast times. Lemkos were made part of the Austria province of Galicia in 1772.[5] This area was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until its dissolution in 1918, at which point the Lemko-Rusyn Republic (Ruska Lemkivska) declared its independence. Independence did not last long however, and the republic was incorporated into Poland in 1920.

As a result of the forcible deportation of Ukrainians from Poland to the Soviet Union after World War II, the majority of Lemkos in Poland were either resettled from their historic homeland to the prеviously German territories in the North-Western region of Poland or to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[6] Only those Lemkos living the Prešov Region in present-day Slovakia continue to live on their ancestral lands, with the exception of some Lemkos who resettled in their homeland in the late 1950s and afterward. Lemkos are/were neighbours with Slovaks, Carpathian Germans and Lachy sądeckie (Poles) to the west, Pogorzans (Poles) and Dolinians (a Rusyn subgroup) to the north, Ukrainians to the east, and Slovaks to the south.

-

Ethnographic groups of southeasternmost Poland, Lemkos in light blue.

-

Highlander groups of westernmost Ukraine, Lemkos in blue.

Etymology

The name "Lemko" derives from the common expression Lem (Лeм), which can mean "but", "only", or "like" in the Lemko dialect. This word is commonly used in many dialects mainly around eastern Slovakia, Polish and Ukrainian border, and is one distinction between the languages. "Lemko" came into use as an endonym after having been used as an exonym by the neighboring Lyshaks, Boykos and Hutsuls, who do not use that term in their respective dialects. The term in Slovak dialects would be Lemko, in Rusyn dialect it is Lemkiv, in Polish Lemkwich.

Prior to this name, the Lemkos and the Lyshaks described themselves as Rusnaks (Template:Lang-uk, translit. Rusnaky) or Rusyns (Template:Lang-uk, translit. Rusyny), as did the rest of the inhabitants of present-day Western Ukraine in the 19th century and first part of the 20th century. In the late 19th and continuing into the early 20th century, in order to differentiate themselves from ethnic Russians, Ruthenians/Rusyns began to use the ethnonym Ukrainians (Template:Lang-uk, translit. Ukrayintsi). Some Lemkos have accepted the ethnonym, but many consider themselves to be a distinct ethnicity, while some continue to identify themselves as Rusyns.

History

The ethnogenesis of the Lemkos is still being discussed by scholars. According to one theory, the Lemkos (and other Carpatho-Rusyns) are descendants of the White Croats. Some Polish scholars claim that they developed from a Vlach – Rusyn migration in the 14th and 15th centuries. There is also a view that they are refugees from Rus who moved to the Western side of the Carpathian Mountains in the 14th century to escape the Mongol invasion. Some scholars suggest that settlers from Rus' may have arrived earlier to the area traditionally inhabited by Lemkos. Analysis of population genetics shows statistical differences between Lemkos and other Slavic or European populations.[7]

Lemkivshchyna became part of Poland in medieval Piast times. Lemkos became an ethnic minority as part of the Austria province of Galicia in 1772.[5] Mass emigration from this territory to the Western hemisphere for economic reasons began in the late 19th century. After World War I, Lemkos founded two short-lived republics, the Lemko-Rusyn Republic in the west of Galicia, which had a russophile orientation, and the Komancza Republic, with a Ukrainophilic orientation.

It is estimated that about 130,000 to 140,000 Lemkos were living in the Polish part of Lemkivshchyna in 1939. Additional depopulation of these lands occurred during the forced resettlement, initially to the Soviet Union (about 90,000 people) and later to Poland's newly acquired western lands (about 35,000) in the Operation Vistula campaign of the late 1940s. This action was a state ordered removal of the civilian population, in a counter-insurgency operation to remove potential support for guerrilla war being waged by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in south-eastern Poland.

While a small number of Lemkos returned (some 5,000 Lemko families returned to their home regions in Poland between 1957–1958,[8] (they were officially granted the right to return in 1956), the Lemko population in the Polish section of Lemkivschyna only numbers around 10,000–15,000 today. Some 50,000 Lemkos live in the western and northern parts of Poland, where they were sent to populate former German villages in areas ceded to Poland. Among those, 5,863 people identified themselves as Lemko in the 2002 census. However, 60,000 ethnic Lemkos may reside in Poland today. Within Lemkivshchyna, Lemkos live in the villages of Łosie, Krynica, Nowica, Zdynia, Gładyszów, Hańczowa, Zyndranowa, Uście Gorlickie, Bartne, Binczarowa and Bielanka. Additional populations can be found in Mokre, Szczawne, Kulaszne, Rzepedź, Turzańsk, Komańcza, Sanok, Nowy Sącz, and Gorlice.

In 1968 an open-air museum dedicated to Lemko culture was opened in Zyndranowa. Additionally, a Lemko festival is held annually in Zdynia.

Population genetics

There are a few studies of the genetics of Lemkos, and they suggest a common ancestry with other modern Europeans.[9] An analysis of maternal lineages found that Lemkos have the highest frequency of Haplogroup I (mtDNA) found to that date. Haplogroup M* also reaches its regional peak among Lemkos.[7]

Religion

An important aspect of Lemko culture is their deep commitment to Eastern Christianity which was introduced to the Eastern Slavs from Byzantium via Kiev through the efforts of Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. Originally the Lemkos adhered to Orthodoxy, but in order to avoid latinization directly entered into union with Rome in the 17th century. Most Lemkos today are Eastern rite or Byzantine-rite Catholics. In Poland they belong to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church with a Roman Catholic minority, or to the Ruthenian Catholic Church (see also Slovak Greek Catholic Church) in Slovakia. A substantial number belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church. Through the efforts of the martyred priest Fr. Maxim Sandovich (canonized by the Polish Orthodox Church in the 1990s), in the early 20th century, Eastern Orthodoxy was reintroduced to many Lemko areas which had accepted the Union of Brest centuries before.

The distinctive wooden architectural style of the Lemko churches (as opposed to their neighbouring sub-ethnic groups such as the Boikos) is to place the highest cupola of the church building at the entrance to the church, with the roof sloping downward toward the sanctuary.

Language

The Lemkos' language is considered by Ukrainian linguists to be the most western of Ukrainian dialects. The homeland occupied by the Lemkos has been influenced greatly by the languages spoken by neighboring or ruling peoples, so much so that some consider it a separate entity.[10]

Some scholars state that Lemko is the western-most dialect of the Rusyn language,[11][12] which in turn is considered by many Ukrainians to be a dialect of Ukrainian. Lemko speech includes some patterns matching those of the surrounding Polish and Slovak languages, leading some to refer to it as a transitional dialect between Polish and Slovak (some even consider the dialect in Eastern Slovakia to be a dialect of the Slovak language).[citation needed]

Metodyj Trochanovskij published a Lemko Primer ('Bukvar: Perša knyžečka dlja narodnŷch škol') in 1935 and a First Reader ('Druha knyžečka dlja narodnŷch škol') in 1936 for use in schools in the Lemko-speaking area of Poland.[13] These were banned by the Polish government in 1938. Important fieldwork on the Lemko dialect was carried out by the Polish linguist Zdzisław Stieber before their dispersal.

In the late 20th century, some Lemkos/Rusyns, mainly emigres from the region of the southern slopes of the Carpathians in modern-day Slovakia, began codifying a standard grammar for the Lemko dialect. This happened on the 27 January 1995 in Prešov, Slovakia. The Lemko/Rusyn language first became recognised as a codified language.

Slovakia has more than 1,000,000 users of local dialects which would commonly use the word lem.

Lemkos in fiction

Nikolai Gogol's short story "The Terrible Vengeance" ends at Kriváň, now in Slovakia and pictured on the Slovakian euro, in the heart of Lemkivshchyna in the Prešov Region. Avram Davidson makes several references to the Lemko people in his stories.[14] Anna Bibko, mother-in law of the protagonist of All Shall Be Well; and All Shall Be Well; and All Manner of Things Shall Be Well,[15] is a Lemko[16] "guided by her senses of traditionalism and grievance, not necessarily in that order".[17] In the critically acclaimed movie The Deer Hunter the wedding reception scene was filmed in Lemko Hall in the Tremont neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, which had a significant immigrant population of Lemkos at one time.[18] The three main character's surnames, however, appear to be Russian (Michael "Mike" Vronsky, Steven Pushkov, and Nikonar "Nick" Chevotarevich) and the wedding took place in St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral which is also located in Tremont.

Notable Lemkos

- Igor Herbut, Musician

- Bohdan Ihor Antonych, poet

- Thomas Bell, American novelist

- Ivan Krasovs'kyi, Lemko ethnographer/historian

- Seman Madzelan, Lemko Writer and Activist

- Oleksandr Dukhnovych, writer

- Volodymyr Kubiyovych, Ukrainian geographer

- Nikifor, painter

- Petro Trochanowski, Lemko poet,[19] involved with contemporary Lemko issues

- Andrew Kay, inventor of the digital voltmeter (1953), and inductee of the Computer Hall of Fame for founding Kaypro Computer

- Maxim Sandovich, Orthodox saint

- Metodyj Trochanovskij, Lemko grammarian

- Andy Warhol (birth name Warhola), major figure in the pop art movement

- James Warhola, American artist

See also

References

- ^ http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/results/nationality_population/nationality_popul2/select_5/?botton=cens_db&box=5.5W&k_t=00&p=0&rz=1_1&rz_b=2_1 &n_page=1

- ^ a b Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29 January 2013. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ^ http://www.rusinskaobroda.sk/?p=588

- ^ 2001 Ukrainian Census

- ^ a b Levinson, David (1994). Levinson, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia, China. Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. 6. Boston, Massachusetts: G.K. Hall. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8161-1810-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor2-first=missing|editor2-last=(help) - ^ Kordan B (1997). "Making borders stick: population transfer and resettlement in the Trans-Curzon territories, 1944–1949". The International Migration Review. 31 (3): 704–20. doi:10.2307/2547293. JSTOR 2547293. PMID 12292959.

- ^ a b Nikitin, AG; Kochkin IT; June CM; Willis CM; McBain I; Videiko MY (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Boyko, Hutsul and Lemko populations of Carpathian highlands". Human Biology. 81 (1): 43–58. doi:10.3378/027.081.0104. OCLC 432539982. PMID 19589018. Unknown ID 0018-7143.

Lemkos shared the highest frequency of haplogroup I ever reported and the highest frequency of haplogroup M* in the region. MtDNA haplogroup frequencies in Boykos were different from most modern European populations.

- ^ Lemko Republic of Florynka / Ruska narodna respublika Lemkiv

- ^ Willis, Catherine (2006). "Study of the Human Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphism". McNair Scholars Journal. 10 (1). Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ See uk:Лемківський говір

- ^ "The Rusyns". Rusyn. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ Best, Paul Joseph; Moklak, Jarosław, eds. (2000). The Lemkos of Poland : articles and essays. Carpatho-Slavic Studies. Vol. 1–3. New Haven, Cracow: Carpatho-Slavic Studies Group, Historia Iagellonica Press. ISBN 978-83-912018-3-1. OCLC 231621583.

- ^ Horbal, Bogdan (2005). "The Rusyn Movement among the Galician Lemkos". In Custer, Richard D. (ed.). Rusyn-American Almanac of the Carpatho-Rusyn Society 10th Anniversary 2004–2005. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. pp. 81–91.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Davidson, Avram. "The Odd Old Bird". In Davis, Grania; Wessells, Henry (eds.). The Other Nineteenth Century. p. 125. ISBN 0-312-84874-9. OCLC 48249248.

Lemkovarna, the land of the Lemkos, those Slavs forgotten by everyone save themselves

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Wodicka, Tod (2007). All Shall Be Well; and All Shall Be Well; and All Manner of Things Shall Be Well. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42473-1. OCLC 124165798.

- ^ Nicholas Lezard (28 June 2008). "Sympathy for the outsider" (book review). The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

(You could be forgiven for thinking Wodicka has made the Lemkos up. He hasn't.)

- ^ Janet Maslin (24 January 2008). "Mead-Drinking, Gruel-Eating, Sandal-Wearing, Reality-Fleeing Family Guy". New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2009.

- ^ http://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/325#.Vsyj6uZ1VKI

- ^ Mihalasky, Susyn Y (1997). "A Select Bibliography of Polish Press Writing on the Lemko Question". Retrieved 13 December 2009.

Further reading

- Moklak, Jaroslaw. The Lemko Region in the Second Polish Republic: Political and Interdenominational Issues 1918--1939 (2013); covers Old Rusyns, Moscophiles and National Movement Activists, & the political role of the Greek Catholic and Orthodox Churches

- Łemkowie Grupa Etniczna czy Naród?, [The Lemkos: An Ethnic Group or a Nation?], trans. Paul Best Paul Best

- The Lemkos of Poland – Articles and Essays, editor Paul Best and Jarosław Moklak

- The Lemko Region, 1939–1947 War, Occupation and Deportation – Articles and Essays, editor Paul Best and Jarosław Moklak

- Horbal, Bogdan (April 30, 2010). Lemko Studies: A Handbook. East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-639-0. OCLC 286518760.

- Laun, Karen (6 December 1999). "A Fractured Identity: The Lemko of Poland". Central Europe Review. 1 (24).

- Лемкiвскiй календар. (Lemkivskiĭ kalendar)

- Madzelan, Seman (1986). Smak doli (in Polish). Nowy Sącz. OCLC 28484749.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Madzelan, Vasil; Madzelan, Seman (1993). Lemkivshchyna, a Ukrainian Ethnic Group (in Rusyn). Lviv.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Drozd R., Halczak B. Dzieje Ukraińców w Polsce w latach 1921–1989 / Roman Drozd, Bohdan Halczak. – wyd. II, poprawione. – Warszawa : TYRSA, 2010. – 237 s.

- Halczak B. Publicystyka narodowo – demokratyczna wobec problemów narodowościowych i etnicznych II Rzeczypospolitej / Bohdan Halczak. – Zielona Góra : Wydaw. WSP im. Tadeusza Kotarbińskiego, 2000. – 222 s.

- Halczak B. Problemy tożsamości narodowej Łemków / Bohdan Halczak // W: Łemkowie, Bojkowie, Rusini: historia, współczesność, kultura materialna i duchowa / red. nauk. Stefan Dudra, Bohdan Halczak, Andrzej Ksenicz, Jerzy Starzyński . – Legnica – Zielona Góra : Łemkowski Zespół Pieśni i Tańca "Kyczera", 2007 – s. 41–55 .

- Halczak B. Łemkowskie miejsce we wszechświecie. Refleksje o położeniu Łemków na przełomie XX i XXI wieku / Bohdan Halczak // W: Łemkowie, Bojkowie, Rusini – historia, współczesność, kultura materialna i duchowa / red. nauk. Stefan Dudra, Bohdan Halczak, Roman Drozd, Iryna Betko, Michal Šmigeľ . Tom IV, cz. 1 . – Słupsk – Zielona Góra : [b. w.], 2012 – s. 119–133 .

- Дрозд Р., Гальчак Б. Історія українців у Польщі в 1921–1989 роках / Роман Дрозд, Богдан Гальчак, Ірина Мусієнко; пер. з пол. І. Мусієнко. 3-тє вид., випр., допов. – Харків : Золоті сторінки, 2013. – 272 с.

- Andrzej A. Zięba (1997). Łemkowie i łemkoznawstwo w Polsce. Nakł. Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności. ISBN 978-83-86956-29-6.

- Małgorzata Misiak (2006). Łemkowie: w kręgu badań nad mniejszościami etnolingwistycznymi w Europie. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. ISBN 978-83-229-2743-4.

- Polskie Towarzystwo Turystyczno-Krajoznawcze. Zarząd Główny. Komisja Turystyki Górskie.̊ (1987). Łemkowie, kultura, sztuka, język: materiały z symposjum zorganizowanego przez komisję turystyki górskiej ZG PTTK Sanok, DN. 21-24 Września 1983 r. Wydawnictwo PTTK "Kraj".

- Andrzej Kwilecki (1974). Łemkowie: zagadnienie migracji i asymilacji. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe.

- Muzeum Narodowe Rolnictwa i Przemysłu Rolno-Spożywczego (Szreniawa). (2007). Łemkowie: historia i kultura : sesja naukowa Szreniawa, 30 czerwca - 1 lipca 2007. Muzeum Narodowe Rolnictwa i Przemysłu Rolno-Spożywczego w Szreniawie. ISBN 978-83-86624-58-4.

- Jarosław Zwoliński (1996). Łemkowie w obronie własnej: zdarzenia, fakty, tragedie : wspomnienia z Podkarpacia. J. Zwoliński.

- Ewa Michna (1 January 1995). Łemkowie: grupa etniczna czy naród?. Zakład Wydawniczy "Nomos". ISBN 978-83-85527-27-5.

- Roman Reinfuss (1936). Łemkowie: (opis etnograficzny). Druk W. L. Anczyca.

- Tadeusz Zagórzański; Andrzej Wielocha (1984). Łemkowie i Łemkowszczyzna: materiały do bibliografii. SKPB.

External links

- Lemko Portal in Ukraine

- Canadian Lemko Association

- Lemko revival in Poland

- The Zarzad Glowny Zjednoczenia Lemkow w Polsce (Lemko-Ukrainian Union in Poland)

- Lemko.org

- Stowarzyszenie Łemków (Association of Lemkos)

- Lemko Portal in Lviv

- "The Lemko Project" - A blog and resource site about Lemko history, culture and events. English language.

- Ukraine Lemko ethno folk group

- "The bells of Lemkivshchyna. Will the authorities of Ukraine and Poland listen to them", Zerkalo Nedeli, (Mirror Weekly), May 25–31, 2002. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Five questions for Lemko", Zerkalo Nedeli, (Mirror Weekly), January 19–25, 2002. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Metodyj Trochanovskij

- Lemko Portal in Poland