Lwów Ghetto

| |

| Also known as | Template:Lang-de |

|---|---|

The Lwów Ghetto[1] (Template:Lang-de; Template:Lang-pl) was a World War II Jewish ghetto established and operated by Nazi Germany in the city of Lwów (since 1945 Lviv, Ukraine) in the territory of Nazi-administered General Government in German-occupied Poland.

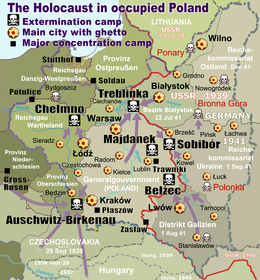

The Lwów Ghetto was one of the largest Jewish ghettos established by Nazi Germany after the joint Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland. The city was a home to over 110,000[1] Jews before the outbreak of World War II in 1939, and by the time the Nazis occupied the city in 1941 that number had increased to over 220,000 Jews,[2] since Jews fled for their lives from Nazi-occupied western Poland into the then relative safety of Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, which included Lwów. The ghetto, set up in the second half of 1941 after the Germans arrived, was liquidated in June 1943 with all its inhabitants who survived prior killings, sent to their deaths in cattle trucks at Bełżec extermination camp and the Janowska concentration camp.[3]

Before the war

On the eve of World War II, the city of Lwów had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland, after Warsaw and Łódź, 99,600 in 1931 (32%) by confession criteria (percent of people of Jewish faith) and numbering 75,300 (24%) by language criteria (percent of people speaking Yiddish or Hebrew as their mother tongue), according to Polish official census.[4] Assimilated Jews, those who perceived themselves as Poles of Jewish faith, constitute the discrepancy between those numbers. By 1939, those numbers were, respectively, several thousand greater. Jews were notably involved in the city's renowned textile industry and had established a thriving center of education and culture, with a wide range of religious and secular political activity including parties and youth movements of the orthodox and Hasidim, Zionists, the Labour Bund, and communists. Assimilated Jews constituted a significant part of Lwów's Polish intelligentsia and academical elites, including such notable ones as Marian Auerbach, Maurycy Allerhand and many others, and greatly contributed to Lwów's cultural center status.

Soviet occupation zone at the onset of World War II

Soon after the outbreak of World War II about 200,000–300,000 Polish Jews fled eastward to Lwów from the Nazi-occupied western part of Poland.[5] The mass influx of refugees in Lwów preceded the formal annexation of the Polish Kresy region by the Soviet Union in accordance with the terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany.[6] Within weeks of the Soviet takeover, all city supplies of grain, corn, wheat flour, beef and other meats, sugar, butter, salt, tobacco, even matches, vanished. By December 1939 up to one thousand people were lining up at various locations to buy bread. In January 1940 no bread was available anywhere in Lwów for a whole week. The price of potatoes rose by 800 per cent.[7]

Many Jews in Lwów under the Soviet rule became the target of state terror like the rest of local citizenry. There were 10,000 Jewish men and women among the hundreds of thousands of Polish nationals deported to Siberia by the Soviet NKVD in 1940. Those deported deep into the USSR who managed to survive in the coldest and harshest climates were almost the only ones who also outlived the catastrophe of the Holocaust.[8]

The Nazi conquest and Pogroms

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

The German army entered the Soviet occupation zone on June 22, 1941 under the codename Operation Barbarossa and a week later, on June 30, 1941 overran the city of Lwów. When the 1st Mountain Division of the German 49th Army Corps took over the city, the gates of all NKVD prisons were opened and, within hours, the scale of Soviet murders revealed. A special commission was formed under SS Judge Hans Tomforde to make a report. Jews were ordered to start removing decomposing bodies from cells and cellars into prison yards. Over 1,500 dead were accounted for at Brygidki. At some prisons, the mountains of putrefacting corpses reaching the basement ceilings forced the Germans to stop counting and wall-off the doors with brickwork. The German propaganda blamed the killings on the Jewish commissars and encouraged local Ukrainians to take their revenge – according to testimonies collected by the Germans, OUN-UPA members were in the majority of prisoners. In early July 1941 SS paramilitary death squads organized the first pogrom against the Jews with the aid of Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. About 4,000 Jews were massacred by Ukrainian nationalists. In late July, another pogrom (known as Petliura Days), took the lives of more than 2,000 Jews.[2][9][10] Some, mostly Ukrainian scholars, argue that the pogroms were in retaliation for the NKVD prisoner massacres of approximately 7,000,[11] and up to 10,000 prisoners,[12] including Polish, Jewish and Ukrainian intellectuals, political activists, and alleged common criminals held at Lwów's three prisons comprising Brygidki, Łąckiego Street and Zamarstynowska Street prison. According to Ukrainian scholars 75-80% of these victims were Ukrainian.[12] The Jews who survived the pogroms as eyewitnesses and victims of the violence present a far more direct view in their memoirs. Of the entire population of Jewish Lwow before World War II estimated to be 150,000; less than 1,000 survived.

Anti-Jewish rhetoric

Although Jews had also been among the victims of the massacre perpetrated by the NKVD and Soviets in retreat, they were collectively accused as a group by the Nazis of having somehow been responsible for it.[9] One theory advanced to "justify" the ensuing anti-Jewish pogrom commonly known as the "Prison Massacre" and mass murder of several thousand Jews is that the Ukrainians had retaliated against them "because some Jews had welcomed the Soviet occupation." Ukrainian historians have posited other theories also, and this is just one among many as to why the Prison Massacre of the Jews occurred.[9]

According to the Jewish survivors of the Ghetto – eyewitnesses to these events – the sole reason for the so-called Prison Massacre was hundreds of years of pent-up Ukrainian hatred for the Jewish population,[13] that had been steeping from the days when Ukrainians were still Ruthenians, subjected to the authority of the Kaiser Franz Josef I during the time when Lemberg was the capital city of the province of Galicia in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, wrote Jakob Weiss. In the eyes of the Jewish survivors, the murder of Ukrainian prisoners gave impetus to the shifting of blame onto the Jews with reasonably foreseeable consequences (i.e. to advance what would soon be called the "Final Solution"). It was craftily set in motion utilizing the nationalistic Ukrainians as "tools" (or in view of the crimes committed against the innocent Jewish civilian population, "accessories") after the Nazi invasion.[9]

During this invasion, according to evidentiary photographs as well as eye witness accounts, Ukrainian Nationalists marched side-by-side with the German Einsatzgruppen "C" and the Wehrmacht "Army Group South" when they entered Lviv. Ukrainian nationalists, UNO, and civilians welcomed the invaders. Some were bearing garlands, waving the Ukrainian Trizub along with the Nazi standard. The Ukrainians (civilians and "nationalists" alike) greeted the invaders with open arms, banners, and floral arrangements.[14] Men displayed a raised arm "Heil Hitler" salute, while the Nazis received embraces and kisses from young women dressed in traditional Ukrainian folk outfits.

The Soviets themselves as well as other witnesses (mostly the few surviving Jews), notably Rabbi David Kahane, author of Lvov Ghetto Diary and former member of the Committee on Religious Affairs of the Lemberg Judenrat, have asserted that it was actually the Nazis themselves that perpetrated the massacre, and then blamed it on the NKVD. But as the pretext went, after filming the devastation they themselves had inflicted, used the "prison massacre" as a pretext to set up the Jews of Lwow; in effect to provide a "cause" for the Ukrainians to vent their hatred. Thus, if we accept the Soviet and Jewish victims' version of the events rather than the version advanced by the Ukrainians (who were the actual rioters and perpetrated the murders), it was the Nazis who "gave license" to the UNO, the Ukrainian nationalists, the Ukrainian People's Militia (soon to become the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police), and Ukrainian citizenry (identified simply by yellow armbands), to conduct a full blown massacre in which at least 2000 Jewish men were killed. Note that at this early stage of the (recently named) "Holocaust by Bullets" in Ukraine (technically General Government Galicia beginning in August, 1941), women were still only harassed and beaten. The outright massacres of Jewish men, women, and children would soon follow (see the "Final Solution" in the General Government Galicia).[15]

A second pogrom took place in the last days of July 1941 and was named the "Petlura Days" after the assassinated Ukrainian leader and pogromist Symon Petliura.[16][17] This pogrom was organized by the Nazis, but carried out by the Ukrainians, as a prologue to the total annihilation of the Jewish population of Lwów. Somewhere in the neighborhood of between 5,000–7,000 Jews were brutally beaten and more than 2,000 murdered[2] in this massacre.[18] In addition, some 3,000 persons, mostly Jews, were executed in the municipal stadium by the German military.[18]

The Ghetto

Following the Nazi takeover, one of the most prolific mass murderers in the SS, Gruppenführer Fritz Katzmann, became the Higher SS and Police Leader (SSPF) of Lwów.[19] On his orders the Ghetto called Jüdischer Wohnbezirk was established on November 8, 1941 in the northern part of the city. Some 80,000 Jews were ordered to move there by December 15, 1941 and all Poles and Ukrainians to move out.[20] The neighborhood which was designated to form the Jewish quarter was Zamarstynów (today Template:Lang-uaЗамарстинів). Before the war it was one of the poorest suburbs of Lwów. German police also began a series of "selections" in an operation called "Action under the bridge" - 5,000 elderly and sick Jews were shot as they crossed under the rail bridge on Pełtewna Street (called bridge of death by the Jews) moving slowly toward the gate. Eventually, between 110,000 and 120,000 Jews were forced into the new ghetto. The living conditions there were extremely poor, coupled with severe overcrowding. For example, food rations allocated to the Jews were estimated to equal only 10% of the German and 50% of the Ukrainian or Polish rations.[21]

The Germans established a Jewish police force called the Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst Lemberg wearing dark blue Polish police uniforms from before World War II, but with the Polish insignia replaced by a Magen David and the new letters J.O.L. in various positions on their uniform. They were given rubber truncheons. Their ranks numbered from 500 to 750 policemen.[21] The Jewish police force answered to the Jewish National city council known as the Judenrat, which in turn answered to the Gestapo.

Deportations

The Lemberg Ghetto was one of the first to have Jews transported to the death camps as part of Aktion Reinhard. Between March 16 and April 1, 1942, 15,000 Jews were taken to the Kleparów railway station and deported to the Belzec extermination camp. Following these initial deportations, and death by disease and random shootings, around 86,000 Jews officially remained in the ghetto, though there were many more not recorded. During this period, many Jews were also forced to work for the Wehrmacht and the ghetto's German administration, especially in the nearby Janowska labor camp. On June 24–25, 1942, 2,000 Jews were taken to the labor camp; only 120 were used for forced labor, and all of the others were shot.

Between August 10–31, 1942, the "Great Aktion" was carried out, where between 40,000 and 50,000 Jews were rounded up, gathered at transit point placed in Janowska camp and then deported to Belzec. Many who were not deported, including local orphans and hospital inpatients, were shot. On September 1, 1942, the Gestapo hanged the head of Lwów’s Judenrat and members of the ghetto's Jewish police force on balconies of Judenrat's building at Łokietka street and Hermana street corner. Around 65,000 Jews remained while winter approached with no heating or sanitation, leading to an outbreak of typhus.

Between January 5–7, 1943, another 15,000-20,000 Jews, including the last members of the Judenrat, were shot outside of the town on the orders of Fritz Katzmann. After this aktion in January 1943 Judenrat was dissolved, that what remained of the ghetto was renamed Judenlager Lemberg (Jewish Camp Lwów), thus formally redesigned as labor camp with about 12,000 legal Jews, able to work in German war industry and several thousands illegal Jews (mainly women, children and elderly) hiding in it.[21]

In the beginning of June 1943 Germans decided to finally end the existence of the Jewish quarter and its inhabitants. As Nazis entered the Ghetto they met some sporadic acts of armed resistance, but most of the Jews were trying to hide themselves in earlier prepared hideouts (so called bunkers). In effect many buildings were suffused with gasoline and burned in order to "flush out" Jews from their hiding places. Some Jews managed to escape or to conceal themselves in the sewer system.

By the time that the Soviet Red Army entered Lwów on July 26, 1944, only a few hundred Jews remained in the city. Number varies from 200 to 900 (823 according to data of Jewish Provisional Committee in Lwów, Template:Lang-pl from 1945).

Among its notable inhabitants was Chaim Widawski, who disseminated news about the war picked up with an illegal radio.[22] Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal was one of the best-known Jewish inhabitants of Lemberg Ghetto to survive the war (as his memoirs (The Executioners Among Us) indicate, he was saved from execution by a Ukrainian policeman), though he was later transported to a concentration camp, rather than remaining in the ghetto.

See also

- In Darkness 2011 historical drama by David F. Shamoon and Agnieszka Holland

Notes

- ^ a b Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum encyclopedia of camps and ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. Volume II: Ghettos in German-occupied Eastern Europe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 802–805. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c "Lvov". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ The statistical data compiled on the basis of "Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland" by Virtual Shtetl Museum of the History of the Polish Jews Template:En icon, as well as "Getta Żydowskie," by Gedeon, Template:Pl icon and "Ghetto List" by Michael Peters at www.deathcamps.org/occupation/ghettolist.htm Template:En icon. Accessed July 12, 2011.

- ^ Mały Rocznik Statystyczny 1939 (Polish statistical yearbook of 1939), GUS, Warsaw, 1939

- ^ Mark Paul (2013). Neighbours On the Eve of the Holocaust (PDF file, direct download). PEFINA Press, Toronto. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Stefan Szende, The Promise Hitler Kept, London 1945, p. 124. OCLC: 758315597.

- ^ Wołodymyr Baran (2012). Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość. Pismo naukowe poświęcone historii najnowszej [Memory and Justice 1 (19) 2012] (PDF file, direct download). Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. pp. 489–490. ISSN 1427-7476. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Dr. Filip Friedman (2007). Zaglada Zydow Lwowskich [The Annihilation of Lvovian Jews] (Internet Archive). Wydawnictwa Centralnej Zydowskiej Komisji Historycznej przy Centralnym Komitecie Zydow Polskich Nr 4. OCLC 38706656. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

English translation of the Russian edition (excerpts).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); External link in|quote= - ^ a b c d "Lemberg/Lvov massacre "Deutsche Wochenschau" Newsreel". Archives database. U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. July 1941. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Społeczność żydowska przed 1989 – Ukraina / Львівська область (obwód lwowski)". Lwów. Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich Virtual Shtetl. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Jerzy Węgierski, Lwów pod okupacją sowiecką 1939-1941 , Warszawa 1991, Editions Spotkania, ISBN 83-85195-15-7 p. 273.

- ^ a b Євген Наконечний (2006). "Шоа" у Львові (Source: Історія @ EX.UA). Publisher: Львів: ЛА «Піраміда». pp. 98–99 or 50 in current document (1/284 or 1/143 digitized). ISBN 966-8522-47-8. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

DjVu Document (7.7 MB) at Nakonechnyi_Yevhen.Shoa_u_Lvovi.djvu

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Jakob Weiss (2011). The Lemberg Mosaic. Alderbrook Press. p. 207. ISBN 0983109109.

- ^ David Bankier, Israel Gutman. Nazi Europe and the Final Solution. Berghahn Books. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ David Kahana (1990). Lvov Ghetto Diary (Google Book snippet). University of Massachusetts Press. pp. c. ISBN 0870237268. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Lwów". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "July 25: Pogrom in Lwów". Chronology of the Holocaust. Yad Vashem. 2004. Retrieved 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Richard Breitman. Himmler and the 'Terrible Secret' among the Executioners. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 26, No. 3/4, The Impact of Western Nationalisms: Essays Dedicated to Walter Z. Laqueur on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday (Sep., 1991), pp. 431-451

- ^ Waldemar „Scypion” Sadaj (January 27, 2010). "Fritz Friedrich Katzmann". SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Waffen-SS und Polizei. Allgemeine SS & Waffen-SS. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ Claudia Koonz (November 2, 2005). "SS Man Katzmann's "Solution of the Jewish Question in the District of Galicia"" (PDF). The Raul Hilberg Lecture. University of Vermont: 2, 11, 16–18. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Filip Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich (Extermination of the Jews of Lwów) OCLC 38706656.

- ^ Trunk, Isaiah; Shapiro, Robert Moses (2006). Łódź Ghetto: a history. Indiana University Press. p. lvi. ISBN 978-0-253-34755-8.

References

- Aharon Weiss, Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust vol. 3, pp. 928–931. Map, photos

- Filip Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich (Extermination of the Jews of Lwów) - online in Polish, Ukrainian and Russian

Further reading

- Marek Herman, From the Alps to the Red Sea. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers and Beit Lohamei Haghetaot, 1985. pp. 14–60

- David Kahane, Lvov Ghetto Diary. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1990. ISBN 0-87023-726-8 (Published in Hebrew as Yoman getto Lvov, Jerusalem:Yad Vashem, 1978)

- Dr Filip Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich, Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna, Centralny Komitet Żydów Polskich, Nr 4, Łódź 1945

- Weiss, Jakob, The Lemberg Mosaic. New York : Alderbrook Press, 2010. See also The Lemberg Mosaic (Wikipedia).

- Chiger, Krystyna, The Girl in the Green sweater: A life in Holocaust's Shadow, Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 1429961252

- Leon Weliczker Wells, The Janowska Road (original publication Macmillan, 1963). Amazon: Halo Pr, 1999. ISBN 089604159X

External links

- US Holocaust Museum information on Lviv

- Database of names from the Lviv Ghetto

- Dr Filip Fiedman, pl:Filip Friedman