Mandolin

An American A-style left-handed mandolin, with F-holes | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Plucked string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.321-6 (Neapolitan) or 321.322-6 (flat-backed) (Composite chordophone sounded by a plectrum) |

| Developed | Mid 18th century from the mandolino |

| Playing range | |

(a regularly tuned mandolin with 14 frets to body) | |

| Related instruments | |

A mandolin (Template:Lang-it pronounced [mandoˈliːno]; literally "small mandola") is a musical instrument in the lute family and is usually plucked with a plectrum or "pick". It commonly has four courses of doubled metal strings tuned in unison (8 strings), although five (10 strings) and six (12 strings) course versions also exist. The courses are normally tuned in a succession of perfect fifths. It is the soprano member of a family that includes the mandola, octave mandolin, mandocello and mandobass.

There are many styles of mandolin, but three are common, the Neapolitan or round-backed mandolin, the carved-top mandolin and the flat-backed mandolin. The round-back has a deep bottom, constructed of strips of wood, glued together into a bowl. The carved-top or arch-top mandolin has a much shallower, arched back, and an arched top—both carved out of wood. The flat-backed mandolin uses thin sheets of wood for the body, braced on the inside for strength in a similar manner to a guitar. Each style of instrument has its own sound quality and is associated with particular forms of music. Neapolitan mandolins feature prominently in European classical music and traditional music. Carved-top instruments are common in American folk music and bluegrass music. Flat-backed instruments are commonly used in Irish, British and Brazilian folk music. Some modern Brazilian instruments feature an extra fifth course tuned a fifth lower than the standard fourth course.

Other mandolin varieties differ primarily in the number of strings and include four-string models (tuned in fifths) such as the Brescian and Cremonese, six-string types (tuned in fourths) such as the Milanese, Lombard and the Sicilian and 6 course instruments of 12 strings (two strings per course) such as the Genoese.[1] There has also been a twelve-string (three strings per course) type and an instrument with sixteen-strings (four strings per course).

Much of mandolin development revolved around the soundboard (the top). Pre-mandolin instruments were quiet instruments, strung with as many as six courses of gut strings, and were plucked with the fingers or with a quill. However, modern instruments are louder—using four courses of metal strings, which exert more pressure than the gut strings. The modern soundboard is designed to withstand the pressure of metal strings that would break earlier instruments. The soundboard comes in many shapes—but generally round or teardrop-shaped, sometimes with scrolls or other projections. There is usually one or more sound holes in the soundboard, either round, oval, or shaped like a calligraphic F (f-hole). A round or oval sound hole may be covered or bordered with decorative rosettes or purfling.[2][3]

History

Mandolins evolved from the lute family in Italy during the 17th and 18th centuries, and the deep bowled mandolin, produced particularly in Naples, became common in the 19th century.

Early precursors

Dating to around c. 13,000 BC, a cave painting in the Trois Frères cave in France depicts what some believe to be a musical bow, a hunting bow used as a single-stringed musical instrument.[4][5]

From the musical bow, families of stringed instruments developed; since each string played a single note, adding strings added new notes, creating bow harps, harps and lyres.[6] In turn, this led to being able to play dyads and chord. Another innovation occurred when the bow harp was straightened out and a bridge used to lift the strings off the stick-neck, creating the lute.[7]

First lutes

The plucked family of stringed instruments included lute-like instruments in Mesopotamia prior to 3000 BC .[8] A cylinder seal from c. 3100 BC or earlier (now in the possession of the British Museum) shows what is thought to be a woman playing a stick lute.[8][9]

The Mesopotamian lutes developed into a long variety and a short.[10] The line of short lutes was further developed to the east of Mesopotamia, in Bactria and Gandhara, into a short, almond-shaped lute.[11][12][13]

Persian barbat, Arab oud

Andalusia

Bactria and Gandhara became part of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD). Under the Sasanians, a short almond shaped lute from Bactria came to be called the barbat or barbud, which was developed into the later Islamic world's oud or ud.[15] When the Moors conquered Andalusia in 711 AD, they brought their ud along, into a country that had already known a lute tradition under the Romans, the pandura.

During the 8th and 9th centuries, many musicians and artists from across the Islamic world flocked to Iberia.[16] Among them was Abu l-Hasan ‘Ali Ibn Nafi‘ (789-857),[17][18] a prominent musician who had trained under Ishaq al-Mawsili (d. 850) in Baghdad and was exiled to Andalusia before 833 AD. He taught and has been credited with adding a fifth string to his oud[15] and with establishing one of the first schools of music in Córdoba.[19]

By the 11th century, Muslim Iberia had become a center for the manufacture of instruments. These goods spread gradually to Provence, influencing French troubadours and trouvères and eventually reaching the rest of Europe.

From Sicily to Germany

Beside the introduction of the lute to Spain (Andalusia) by the Moors, another important point of transfer of the lute from Arabian to European culture was Sicily, where it was brought either by Byzantine or later by Muslim musicians.[20] There were singer-lutenists at the court in Palermo following the Norman conquest of the island from the Muslims, and the lute is depicted extensively in the ceiling paintings in the Palermo’s royal Cappella Palatina, dedicated by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily in 1140.[20] His Hohenstaufen grandson Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (1194 - 1250) continued integrating Muslims into his court, including Moorish musicians.[21] By the 14th century, lutes had disseminated throughout Italy and, probably because of the cultural influence of the Hohenstaufen kings and emperor, based in Palermo, the lute had also made significant inroads into the German-speaking lands.

European lute beginnings

A distinct European tradition of lute development is noticeable in pictures and sculpture from the 13th century onward. As early as the beginning of the 14th century, strings were doubled into courses on the miniature lute or gittern, used throughout Europe. The small zigzag-shaped soundhole became a round soundhole covered with a decoration. The mandore, appeared in the late 16th century, and the mandolino or Baroque mandolin in the 17th century.

Development in Italy, birth of Neapolitan mandolin

The mandore was not a final form, and the design was tinkered with wherever it was built. The Italians redesigned it and produced the mandolino (a small catgut-strung mandola with 4, 5 or 6 courses tuned e' a' d g; b e a d g; G b e a d g, that we may call Baroque mandolin and always played with finger-style, never with a plectrum until the second half of the XVIII century. At this point, all such instruments were strung with gut strings.

Vinaccia

First metal-string mandolins

The first evidence of modern metal-string mandolins is from literature regarding popular Italian players who travelled through Europe teaching and giving concerts. Notable are Signor Leone and Giovanni Battista Gervasio, who travelled widely between 1750 and 1810.[3][23] This, with the records gleaned from the Italian Vinaccia family of luthiers in Naples, Italy, led some musicologists to believe that the modern steel-string mandolins were developed in Naples by the Vinaccia family.

There is confusion currently as to the name of the eldest Vinaccia luthier who first ran the shop. His name has been put forth as Gennaro Vinaccia (active c. 1710 to c. 1788) and Nic. Vinaccia.[24] His son Antonio Vinaccia was active c. 1734 to c. 1796.[25] An early extant example of a mandolin is one built by Antonio Vinaccia in 1759, which resides at the University of Edinburgh.[26] Another is by Giuseppe Vinaccia, built in 1893, is also at the University of Edinburgh.[27] The earliest extant mandolin was built in 1744 by Antonio's son, Gaetano Vinaccia. It resides in the Conservatoire Royal de Musique in Brussels, Belgium.[28]

Family mandolin modified to create Neapolitan mandolin

Gaetano's son, Pasquale Vinaccia (b.1806-d.1881), modernized the mandolin, adding features, creating the Neapolitan mandolin c. 1835.[29][30] Pasquale remodeled, raised and extended the fingerboard to 17 frets, introduced stronger wire strings made of high-tension steel and substituted a machine head for the friction tuning pegs, then standard.[29][31] The new wire strings required that he strengthen the mandolin's body, and he deepened the mandolin's bowl, giving the tonal quality more resonance.[29]

Calace, Embergher and others

Other luthiers who built mandolins included Raffaele Calace (1863 onwards) in Naples, Luigi Embergher[32] (1856–1943) in Rome and Arpino, the Ferrari family (1716 onwards, also originally mandolino makers) in Rome, and De Santi (1834–1916) in Rome. The Neapolitan style of mandolin construction was adopted and developed by others, notably in Rome, giving two distinct but similar types of mandolin – Neapolitan and Roman.[33]

Rising and falling fortunes

First wave

The transition from the mandolino to the mandolin began around 1744 with the designing of the metal-string mandolin by the Vinaccia family, 3 brass strings and one of gut, using friction tuning pegs on a fingerboard that sat "flush" with the sound table.[34] The mandolin grew in popularity over the next 60 years, in the streets where it was used by young men courting and by street musicians, and in the concert hall.[35] After the Napoleonic Wars of 1815, however, its popularity began to fall.[36] The 19th century produced some prominent players, including Bartolomeo Bortolazzi of Venice and Pietro Vimercati.[37] However, professional virtuosity was in decline,[37] and the mandolin music changed as the mandolin became a folk instrument; "the large repertoire of notated instrumental music for the mandolino and the mandoline was completely forgotten". The export market for mandolins from Italy dried up around 1815, and when Carmine de Laurentiis wrote a mandolin method in 1874, the Music World magazine wrote that the mandolin was "out of date."[38] Salvador Léonardi mentioned this decline in his 1921 book, Méthode pour Banjoline ou Mandoline-Banjo, saying that the mandolin had been declining in popularity from previous times.[39]

It was during this slump in popularity (specifically in 1835) that Pasquale Vinaccia made his modifications to the instrument that his family made for generations, creating the Neapolitan mandolin.[34] The mandolin was largely forgotten outside of Italy by that point, but the stage was set for it to become known again, starting with the Paris Exposition in 1878.[40]

Second wave, the Golden Age of mandolins

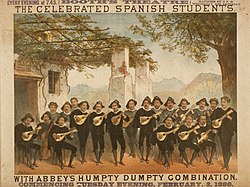

Beginning with the Paris Exposition of 1878, the instrument's popularity rebounded. The Exposition was one of many stops for a popular new performing group the Estudiantes Españoles (Spanish Students).[41] They danced and played guitars, violins and the bandurria, which became confused with the mandolin.[41] Along with the energy and awareness created by the day's hit sensation, a wave of Italian mandolinists travelled Europe in the 1880s and 1890s and in the United States by the mid-1880s, playing and teaching their instrument.[42] The instrument's popularity continued to increase during the 1890s and mandolin popularity was at its height in "early years of the 20th century."[43] Thousands were taking up the instrument as a pastime, and it became an instrument of society, taken up by young men and women.[43] Mandolin orchestras were formed worldwide, incorporating not only the mandolin family of instruments, but also guitars, double basses and zithers.

That era (from the late 19th century into the early 20th century) has come to be known as the "Golden Age" of the mandolin.[44] The term is used online by mandolin enthusiasts to name the time period when the mandolin had become popular, when mandolin orchestras were being organized worldwide, and new and high-quality instruments were increasingly common.

After the First World War, the instrument's popularity again fell, although gradually.[45] Reasons cited included the rise of Jazz, for which the instrument was too quiet. Also the changing pace of life was cited, as people became busier and as modern conveniences (phonograph records, bicycle and automobiles, outdoor sports) competed with learning to play an instrument for fun.[45]

Aftermath

The second decline was not as complete as the first. Thousands of people had learned to play the instrument. Even as the second wave of mandolin popularity declined in the early 20th century, new versions of the mandolin began to be used in new forms of music.[46] Luthiers created the resonator mandolin, the flatback mandolin, the carved-top or arched-top mandolin, the mandolin-banjo and the electric mandolin. Musicians began playing it in Celtic, Bluegrass, Jazz and Rock-n-Roll styles — and Classical too.

Construction

Mandolins have a body which acts as a resonator, attached to a neck. The resonating body may be shaped as a bowl (necked bowl lutes) or a box (necked box lutes). Traditional Italian mandolins, such as the Neapolitan mandolin, meet the necked bowl description.[47] The necked box instruments include the carved top mandolins and the flatback mandolins.[48]

Strings run between mechanical tuning machines at the top of the neck to a tailpiece that anchors the other end of the strings. The strings are suspended over the neck and soundboard and pass over a floating bridge.[49] The bridge is kept in contact with the soundboard by the downward pressure from the strings. The neck is either flat or has a slight radius, and is covered with a fingerboard with frets.[50][51][52] The action of the strings on the bridge causes the soundboard to vibrate, producing sound.[53]

Like any plucked instrument, mandolin notes decay to silence rather than sound out continuously as with a bowed note on a violin, and mandolin notes decay faster than larger stringed instruments like the guitar. This encourages the use of tremolo (rapid picking of one or more pairs of strings) to create sustained notes or chords. The mandolin's paired strings facilitate this technique: the plectrum (pick) strikes each of a pair of strings alternately, providing a more full and continuous sound than a single string would.

Various design variations and amplification techniques have been used to make mandolins comparable in volume with louder instruments and orchestras, including the creation of mandolin-banjo hybrid with the louder banjo, adding metal resonators (most notably by Dobro and the National String Instrument Corporation) to make a resonator mandolin, and amplifying electric mandolins through amplifiers.

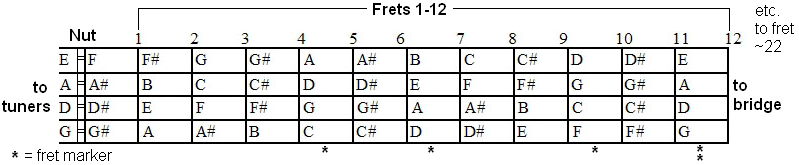

Tuning

A variety of different tunings are used. Usually, courses of 2 adjacent strings are tuned in unison. The most common tuning by far, G3-D4-A4-E5, is the same as violin tuning:

- fourth (lowest tone) course: G3 (196.00 Hz)

- third course: D4 (293.66 Hz)

- second course: A4 (440.00 Hz; A above middle C)

- first (highest tone) course: E5 (659.25 Hz)

Note that the numbers of Hz shown above assume a 440 Hz A, standard in most parts of the western world. Some players use As up to 10 Hz above or below a 440, mainly outside of the United States.

Other tunings exist, including "cross-tunings," in which the usually doubled string runs are tuned to different pitches. Additionally, guitarists may sometimes tune a mandolin to mimic a portion of the intervals on a standard guitar tuning to achieve familiar fretting patterns.

Mandolin family

Soprano

The mandolin is the soprano member of the mandolin family, as the violin is the soprano member of the violin family. Like the violin, its scale length is typically about 13 inches (330 mm). Modern American mandolins modelled after Gibsons have a longer scale, about 13-7/8" (352 mm). The strings in each of its double-strung courses are tuned in unison, and the courses use the same tuning as the violin: G3-D4-A4-E5.

- The piccolo or sopranino mandolin is a rare member of the family, tuned one octave above the mandola and one fourth above the mandolin (C4-G4-D5-A5); the same relation as that of the piccolo or sopranino violin to the violin and viola. One model was manufactured by the Lyon & Healy company under the Leland brand. A handful of contemporary luthiers build piccolo mandolins. Its scale length is typically about 9.5 inches (240 mm).

Alto

- The mandola (US and Canada), termed the tenor mandola in Britain and Ireland and liola or alto mandolin in continental Europe, which is tuned to a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the viola to the violin. Some also call this instrument the "alto mandola." Its scale length is typically about 16.5 inches (420 mm). It is normally tuned like a viola (fifth below the mandolin): C3-G3-D4-A4 .

Tenor

- The octave mandolin (US and Canada), termed the octave mandola in Britain and Ireland and mandola in continental Europe, is tuned an octave below the mandolin: G2-D3-A3-E4. ITs relationship to the mandolin is that of the tenor violin to the violin. Octave mandolin scale length is typically about 20 inches (500 mm), although instruments with scales as short as 17 inches (430 mm) or as long as 21 inches (530 mm) are not unknown.

- The Irish bouzouki is also considered a member of the mandolin family; although derived from the Greek bouzouki (a long-necked lute), it is constructed like a flat-backed mandolin and uses fifth-based tunings, most often G2-D3-A3-E4 (an octave below the mandolin)-- in which case it essentially functions as an octave mandolin. Common alternate tunings include: G2-D3-A3-D4, A2-D3-A3-D4 or A2-D3-A3-E4. Although the Irish bouzouki's bass course pairs are most often tuned in unison, on some instruments one of each pair is replaced with a lighter string and tuned in octaves, in the fashion of the 12-string guitar. While occupying the same range as the octave mandolin/octave mandola, the Irish bouzouki is theoretically distinguished from the former instrument by its longer scale length, typically from 22 inches (560 mm) to 24 inches (610 mm), although scales as long as 26 inches (660 mm), which is the usual Greek bouzouki scale, are not unknown. In modern usage, however, the terms "octave mandolin" and "Irish bouzouki" are often used interchangeably to refer to the same instrument.

- The modern cittern many also be loosely included in an "extended" mandolin family. It resembles the flatback mandolins, but predates them, dating back to the Renaissance. It is typically a five course (ten string) instrument having a scale length between 20 inches (500 mm) and 22 inches (560 mm). The instrument is most often tuned to either D2-G2-D3-A3-D4 or G2-D3-A3-D4-A4, and is essentially an octave mandola with a fifth course at either the top or the bottom of its range. Some luthiers, such as Stefan Sobell also refer to the octave mandola or a shorter-scaled Irish bouzouki as a cittern, irrespective of whether it has four or five courses.

Baritone/Bass

- The mandolone was a Baroque member of the mandolin family in the bass range that was surpassed by the mandocello. Built as part of the Neapolitan mandolin family.

- The mandocello, which is classically tuned to an octave plus a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the cello to the violin: C2-G2-D3-A3. Its scale length is typically about 25 inches (635 mm). A typical violoncello scale is 27" (686 mm).

- The Greek laouto or laghouto (long-necked lute) is similar to a mandocello, ordinarily tuned C3/C2-G3/G2-D3/D3-A3/A3 with half of each pair of the lower two courses being tuned an octave high on a lighter gauge string. The body is a staved bowl, the saddle-less bridge glued to the flat face like most ouds and lutes, with mechanical tuners, steel strings, and tied gut frets. Modern laoutos, as played on Crete, have the entire lower course tuned to C3, an reentrant octave above the expected low C. Its scale length is typically about 28 inches (712 mm).

Contrabass

- The mando-bass most frequently has 4 single strings, rather than double courses, and is tuned in fourths like a double bass or an acoustic bass guitar—E1-A1-D2-G2. These were made by the Gibson company in the early 20th century, but appear to have never been very common. A smaller scale four-string mandobass, usually tuned in fifths—G1-D2-A2-E2 (two octaves below the mandolin) -- was produced which, though not as resonant as the larger instrument, was often preferred by players as easier to handle and more portable.[54][55] Reportedly, however, most mandolin orchestras preferred to use the ordinary double bass, rather than a specialised mandolin family instrument. Calace and other Italian makers predating Gibson also made mandolin-basses.

The relatively rare eight-string mandobass, or tremolo-bass also exists, with double courses like the rest of the mandolin family, and is tuned either G1-D2-A2-E3, two octaves lower than the mandolin, or C1-G1-D2-A2, two octaves below the mandola.[56][57]

Variations

Bowlback

Bowlback mandolins (also known as roundbacks), are used worldwide. They are most commonly manufactured in Europe, where the long history of mandolin development has created local styles. However, Japanese luthiers also make them.

Neapolitan and Roman styles

The Neapolitan style has an almond-shaped body resembling a bowl, constructed from curved strips of wood. It usually has a bent sound table, canted in two planes with the design to take the tension of the 8 metal strings arranged in four courses. A hardwood fingerboard sits on top of or is flush with the sound table. Very old instruments may use wooden tuning pegs, while newer instruments tend to use geared metal tuners. The bridge is a movable length of hardwood. A pickguard is glued below the sound hole under the strings.[28][29][58] European roundbacks commonly use a 13-inch scale instead of the 13.876 common on archtop Mandolins.[59]

Intertwined with the Neapolitan style is the Roman style mandolin, which has influenced it.[60] The Roman mandolin had a fingerboard that was more curved and narrow.[60] The fingerboard was lengthened over the sound hole for the e strings, the high pitched strings.[60] The shape of the back of the neck was different, less rounded with an edge, the bridge was curved making the g strings higher.[60] The Roman mandolin had mechanical tuning gears before the Neapolitan.[60]

Prominent Italian manufacturers include Vinaccia (Naples), Embergher (Rome) and Calace (Naples).[61] Other modern manufacturers include Lorenzo Lippi (Milan), Hendrik van den Broek (Netherlands), Brian Dean (Canada), Salvatore Masiello and Michele Caiazza (La Bottega del Mandolino) and Ferrara, Gabriele Pandini.[59][59]

Lombardic styles, Milanese and Brescian

Another family of bowlback mandolins came from Milan and Lombardy.[62] These mandolins are closer to the mandolino or mandore than other modern mandolins.[62] They are shorter and wider than the standard Neapolitan mandolin, with a shallow back.[63] The instruments have 6 strings, 3 wire treble-strings and 3 gut or wire-wrapped-silk bass-strings.[62][63] The strings ran between the tuning pegs and a bridge that was glued to the soundboard, as a guitar's. The Lombardic mandolins were tuned g b e' a' d" g".[63] A developer of the Milanese stye was Antonio Monzino (Milan) and his family who made them for 6 generations.[62]

Samuel Adelstein described the Lombardi mandolin in 1893 as wider and shorter than the Neapolitan mandolin, with a shallower back and a shorter and wider neck, with six single strings to the regular mandolin's set of 4.[64] The Lombardi was tuned C, D, A, E, B, G.[64] The strings were fastened to the bridge like a guitar's.[64] There were 20 frets, covering three octaves, with an additional 5 notes.[64] When Adelstein wrote, there were no nylon strings, and the gut and single strings "do not vibrate so clearly and sweetly as the double steel string of the Neapolitan."[64]

Brescian Mandolin

Brescian mandolins that have survived in museums have four gut strings instead of six.[65] The mandolin was tuned in fifths, like the Neapolitan mandolin.[65]

Cremonese mandolin

In his 1805 mandolin method, Anweisung die Mandoline von selbst zu erlernen nebst einigen Uebungsstucken von Bortolazzi, Bartolomeo Bortolazzi popularised the Cremonese mandolin, which had four single-strings and a fixed bridge, to which the strings were attached.[66][67] Bortolazzi said in this book that the new wire strung mandolins were uncomfortable to play, when compared with the gut-string instruments.[66] Also, he felt they had a "less pleasing...hard, zither-like tone" as compared to the gut string's "softer, full-singing tone."[66] He favored the four single strings of the Cremonese instrument, which were tuned the same as the Neapolitan.[66][67]

Manufacturers outside of Italy

In the United States, when the bowlback was being made in numbers, Lyon and Healy was a major manufacturer, especially under the "Washburn" brand.[61] Other American manufacturers include Martin, Vega, and Larson Brothers.[61]

In Canada, Brian Dean has manufactured instruments in Neapolitan, Roman, German and American styles[68] but is also known for his original 'Grand Concert' design created for American virtuoso Joseph Brent.[69]

German manufacturers include Albert & Mueller, Dietrich, Klaus Knorr, Reinhold Seiffert and Alfred Woll.[59][61] The German bowlbacks use a style developed by Seiffert, with a larger and rounder body.[59]

Japanese brands include Kunishima and Suzuki.[70] Other Japanese manufacturers include Oona, Kawada, Noguchi, Toichiro Ishikawa, Rokutaro Nakade, Otiai Tadao, Yoshihiko Takusari, Nokuti Makoto, Watanabe, Kanou Kadama and Ochiai.[59][71]

Archtop

At the very end of the 19th century, a new style, with a carved top and back construction inspired by violin family instruments began to supplant the European-style bowl-back instruments in the United States. This new style is credited to mandolins designed and built by Orville Gibson, a Kalamazoo, Michigan luthier who founded the "Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co., Limited" in 1902. Gibson mandolins evolved into two basic styles: the Florentine or F-style, which has a decorative scroll near the neck, two points on the lower body and usually a scroll carved into the headstock; and the A-style, which is pear shaped, has no points and usually has a simpler headstock.

These styles generally have either two f-shaped soundholes like a violin (F-5 and A-5), or an oval sound hole (F-4 and A-4 and lower models) directly under the strings. Much variation exists between makers working from these archetypes, and other variants have become increasingly common. Generally, in the United States, Gibson F-hole F-5 mandolins and mandolins influenced by that design are strongly associated with bluegrass, while the A-style is associated other types of music, although it too is most often used for and associated with bluegrass. The F-5's more complicated woodwork also translates into a more expensive instrument.

Internal bracing to support the top in the F-style mandolins is usually achieved with parallel tone bars, similar to the bass bar on a violin. Some makers instead employ "x-bracing," which is two tone bars mortised together to form an X. Some luthiers now using a "modified x-bracing" that incorporates both a tone bar and x-bracing.

Numerous modern mandolin makers build instruments that largely replicate the Gibson F-5 Artist models built in the early 1920s under the supervision of Gibson acoustician Lloyd Loar. Original Loar-signed instruments are sought after and extremely valuable. Other makers from the Loar period and earlier include Lyon and Healy, Vega and Larson Brothers. Some notable modern American carved mandolin manufacturers include, in addition to Kay, Gibson, Weber, Monteleone and Collings. Mandolins from other countries include The Loar (China), Santa, Rosa (China), Michael Kelly (Korea), Eastman (China), Kentucky (China), Heiden (Canada), Gilchrist (Australia) and Morgan Monroe (China).

Flatback

Flatback mandolins use a thin sheet of wood with bracing for the back, as a guitar uses, rather than the bowl of the bowlback or the arched back of the carved mandolins.

Like the bowlback, the flatback has a round sound hole. This has been sometimes modified to an elongated hole, called a "D" hole. The body has a rounded almond shape with flat or sometimes canted soundboard.[73]

The type was developed in Europe in the 1850s.[73] The French and Germans called it a Portuguese mandolin, although they also developed it locally.[73] The Germans used it in Wandervogel.[74]

The bandolim is commonly used wherever the Spanish and Portuguese took it: in South America, in Brazil (Choro) and in the Philippines.[74]

In the early 1970s English luthier Stefan Sobell developed a large-bodied, flat-backed mandolin with a carved soundboard, based on his own cittern design; this is often called a 'Celtic' mandolin.[75][76]

American forms include the Army-Navy mandolin, the flatiron and the pancake mandolins.

Double top

A variation of the flatback has a double top which encloses a resonating chamber, sound holes on the side and a convex back. It is made by one manufacturer in Israel, luthier Arik Kerman.[77] Players include Avi Avital,[78] Alon Sariel,[79][80] Jacob Reuven,[77] and Tom Cohen.[81]

Tone

The tone of the flatback is described as warm or mellow, suitable for folk music and smaller audiences. The instrument sound does not punch through the other players' sound like a carved top does.

Others

Mandolinetto

Other American-made variants include the mandolinetto or Howe-Orme guitar-shaped mandolin (manufactured by the Elias Howe Company between 1897 and roughly 1920), which featured a cylindrical bulge along the top from fingerboard end to tailpiece and the Vega mando-lute (more commonly called a cylinder-back mandolin manufactured by the Vega Company between 1913 and roughly 1927), which had a similar longitudinal bulge but on the back rather than the front of the instrument.

Banjolin or mandolin-banjo

The mandolin was given a banjo body in an 1882 patent by Benjamin Bradbury of Brooklyn and given the name banjolin by John Farris in 1885.[82] Today banjolin describes an instrument with four strings, while the version with the four courses of double strings is called a mandolin-banjo.

Resonator mandolin

A resonator mandolin or "resophonic mandolin" is a mandolin whose sound is produced by one or more metal cones (resonators) instead of the customary wooden soundboard (mandolin top/face). Historic brands include Dobro and National.

Electric mandolin

As with almost every other contemporary string instrument, another modern variant is the electric mandolin. These mandolins can have four or five individual or double courses of strings.

They have been around since the late 1920s or early 1930s depending on the brand. They come in solid body and acoustic electric forms.

Instruments have been designed that overcome the mandolin's lack of sustain with its plucked notes.[83] Fender released a model in 1992 with an additional string (a high a, above the e string), a tremolo bridge and extra humbucker pickup (total of two).[83] The result was an instrument capable of playing heavy metal style guitar riffs or violin-like passages with sustained notes that can be adjusted as with an electric guitar.[83]

Playing traditions in Italy and worldwide

The international repertoire of music for mandolin is almost unlimited, and musicians use it to play various types of music. This is especially true of violin music, since the mandolin has the same tuning as the violin. Following its invention and early development in Italy the mandolin spread throughout the European continent. The instrument was primarily used in a classical tradition with Mandolin orchestras, so called Estudiantinas or in Germany Zupforchestern appearing in many cities. Following this continental popularity of the mandolin family local traditions appeared outside of Europe in the Americas and in Japan. Travelling mandolin virtuosi like Giuseppe Pettine, Raffaele Calace and Silvio Ranieri contributed to the mandolin becoming a "fad" instrument in the early 20th century.[84] This "mandolin craze" was fading by the 1930s, but just as this practice was falling into disuse, the mandolin found a new niche in American country, old-time music, bluegrass and folk music. More recently, the Baroque and Classical mandolin repertory and styles have benefited from the raised awareness of and interest in Early music, with media attention to classical players such as Israeli Avi Avital, Italian Carlo Aonzo and American Joseph Brent.

Australia

The earliest references to the mandolin in Australia come from Phil Skinner (1903–1991). In his article "Recollections"[85] he mentions a Walter Stent, who was “active in the early part of the century and organised possibly the first Mandolin Orchestra in Sydney.”

Phil Skinner played a key role in 20th century development of the mandolin movement in Australia, and was awarded an MBE in 1979 for services to music and the community. He was born Harry Skinner in Sydney in 1903 and started learning music at age 10 when his uncle tutored him on the banjo. Skinner began teaching part-time at age 18, until the Great Depression forced him to begin teaching full-time and learn a broader range of instruments. Skinner founded the Sydney Mandolin Orchestra, the oldest surviving mandolin orchestra in Australia.[86]

The Sydney Mandolins (Artistic Director: Adrian Hooper) have contributed greatly to the repertoire through commissioning over 200 works by Australian and International composers. Most of these works have been released on Compact Disks and can regularly be heard on radio stations on the ABC and MBS networks. One of their members, mandolin virtuoso Paul Hooper, has had a number of Concertos written for him by composers such as Eric Gross. He has performed and recorded these works with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra. As well, Paul Hooper has had many solo works dedicated to him by Australian composers e.g., Caroline Szeto, Ian Shanahan, Larry Sitsky and Michael Smetanin.

In January 1979, the Federation of Australian Mandolin Ensembles (FAME) Inc. formed. Bruce Morey from Melbourne is the first FAME President. An Australian Mandolin Orchestra toured Germany in May 1980.

Australian popular groups such as My Friend The Chocolate Cake use the mandolin extensively. The McClymonts also use the mandolin, as do Mic Conway's National Junk Band and the Blue Tongue Lizards. Nevertheless, in folk and traditional styles, the mandolin remains more popular in Irish Music and other traditional repertoires.

Belgium

In the early 20th century several mandolin orchestras (Estudiantinas) were active in Belgium. Today only a few groups remain: Royal Estudiantina la Napolitaine (founded in 1904) in Antwerp, Brasschaats mandoline orkest in Brasschaat and an orchestra in Mons (Bergen). Gerda Abts is a well known mandolin virtuoso in Belgium. She is also mandolin teacher and gives lessons in the music academies of Lier, Wijnegem and Brasschaat. She is now also professor mandolin at the music high school “Koninklijk Conservatorium Artesis Hogeschool Antwerpen”. She also gives various concerts each year in different ensembles. She is in close contact to the Brasschaat mandolin Orchestra. Her site is www.gevoeligesnaar.be

Brazil

The mandolin has a long and rich tradition in Brazilian folk music (bandolim in Portuguese), especially in the style called choro. The composer and mandolin virtuoso Jacob do Bandolim did much to popularize the instrument through many recordings, and his influence continues to the present day. Some contemporary mandolin players in Brazil include Jacob's disciple Déo Rian, and Hamilton de Holanda (the former, a traditional choro-style player, the latter an eclectic innovator).

The mandolin came into Brazil by way of Portugal. Portuguese music has a long tradition of mandolins and mandolin-like instruments (see, for example, the Portuguese guitar).

In Brazilian music, the mandolin is almost exclusively a melody instrument. The cavaquinho, a steel stringed instrument similar to a ukulele provides chordal accompaniment. The mandolin's popularity has risen and fallen with instrumental folk music styles, especially choro. The later part of the 20th century saw a renaissance of choro in Brazil, and with it, a revival of the country's mandolin tradition.

Croatia

Mandolin is staple of folk and traditional music on Croatian coast.

Czech and Slovak republics

From Italy mandolin music extended in popularity throughout Europe in the early 20th century, with mandolin orchestras appearing throughout the continent.

In the 21st century an increased interest in bluegrass music, especially in Central European countries such as the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic, has inspired many new mandolin players and builders. These players often mix traditional folk elements with bluegrass.

Finland

Finland has mandolin players rooted in the folk music scene. Prominent names include Petri Hakala, Seppo Sillanpää and Heikki Lahti, who have taught and recorded albums.

France

Prior to the Golden Age of Mandolins, France had a history with the mandolin, with mandolinists playing in Paris until the Napoleonic Wars.[88] The players, teachers and composers included Giovanni Fouchetti, Eduardo Mezzacapo, Gabriele Leon, and Gervasio.[89] During the Golden age itself (1880s-1920s), the mandolin had a strong presence in France. Prominent mandolin players or composers included Jules Cottin and his sister Madeleine Cottin, Jean Pietrapertosa, and Edgar Bara.[89] Paris had dozens of "estudiantina" mandolin orchestras in the early 1900s.[89] Mandolin magazines included L'Estudiantina, Le Plectre, École de la mandolie.[89]

Today, French mandolinists include Patrick Vaillant, a prominent modern player, composer and recording artist for the mandolin, who also organises courses for aspiring players.[90][91]

Greece

The mandolin has a long tradition in the Ionian islands (the Heptanese) and Crete. It has long been played in the Aegean islands outside of the control of the Ottoman Empire. It is common to see choirs accompanied by mandolin players (the mandolinátes) in the Ionian islands and especially in the cities of Corfu, Zakynthos and Kefalonia. The evolution of the repertoire for choir and mandolins (kantádes) occurred during Venetian rule over the islands.

On the island of Crete, along with the lyra and the laouto (lute), the mandolin is one of the main instruments used in Cretan Music. It appeared on Crete around the time of the Venetian rule of the island. Different variants of the mandolin, such as the "mantola," were used to accompany the lyra, the violin, and the laouto. Stelios Foustalierakis reported that the mandolin and the mpoulgari were used to accompany the lyra in the beginning of the 20th century in the city of Rethimno. There are also reports that the mandolin was mostly a woman's musical instrument. Nowadays it is played mainly as a solo instrument in personal and family events on the Ionian islands and Crete.

India

Mandolin music was used in Indian Movies as far back as the 1940s by the Raj Kapoor Studios in movies such as Barsaat. The movie Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) used mandolin in several places.

Adoption of the mandolin in Carnatic music is recent and involves an electric instrument. U. Srinivas has, over the last couple of decades, made his version of the mandolin very popular in India and abroad.

Many adaptations of the instrument have been done to cater to the special needs of Indian Carnatic music. In Indian classical music and Indian light music, the mandolin, which bears little resemblance to the European mandolin, is usually tuned E-B-E-B. As there is no concept of absolute pitch in Indian classical music, any convenient tuning maintaining these relative pitch intervals between the strings can be used. Another prevalent tuning with these intervals is C-G-C-G, which corresponds to Sa-Pa-Sa-Pa in the Indian carnatic classical music style. This tuning corresponds to the way violins are tuned for carnatic classical music. This type of mandolin is also used in Bhangra, dance music popular in Punjabi culture.

Use of the mandolin also spread into Afghanistan and the mandolin is often used in Afghan popular music.

Ireland

The mandolin has become a more common instrument amongst Irish traditional musicians. Fiddle tunes are readily accessible to the mandolin player because of the equivalent tuning and range of the two instruments, and the practically identical (allowing for the lack of frets on the fiddle) left hand fingerings.

Though almost any variety of acoustic mandolin might be adequate for Irish traditional music, virtually all Irish players prefer flat-backed instruments with oval sound holes to the Italian-style bowl-back mandolins or the carved-top mandolins with f-holes favoured by bluegrass mandolinists. The former are often too soft-toned to hold their own in a session (as well as having a tendency to not stay in place on the player's lap), whilst the latter tend to sound harsh and overbearing to the traditional ear. The f-hole mandolin, however, does come into its own in a traditional session, where its brighter tone cuts through the sonic clutter of a pub. Greatly preferred for formal performance and recording are flat-topped "Irish-style" mandolins (reminiscent of the WWI-era Martin Army-Navy mandolin) and carved (arch) top mandolins with oval soundholes, such as the Gibson A-style of the 1920s.

Noteworthy Irish mandolinists include Andy Irvine (who, like Johnny Moynihan, almost always tunes the top E down to D, to achieve an open tuning of GDAD), Paul Brady, Mick Moloney, Paul Kelly and Claudine Langille. John Sheahan and the late Barney McKenna, respectively fiddle player and tenor banjo player with The Dubliners, are also accomplished Irish mandolin players. The instruments used are either flat-backed, oval hole examples as described above (made by UK luthier Roger Bucknall of Fylde Guitars), or carved-top, oval hole instruments with arched back (made by Stefan Sobell in Northumberland). The Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher often played the mandolin on stage, and he most famously used it in the song "Going To My Hometown."

Israel

Israel has four especially prominent mandolinists: Avi Avital,[78] Alon Sariel,[79][80] Jacob Reuven,[77] and Tom Cohen.[81]

Italy

Important performers in the Italitan tradition include Raffaele Calace (luthier, virtuoso and composer of 180 works for many instruments including mandolin), Pietro Denis (whole also composed Sonata for mandolin & continuo No. 1 in D major and Sonata No. 3), Giovanni Fouchetti, Gabriele Leone, Carlo Munier (1859-1911), Giuseppe Branzoli (1835-1909), Giovanni Gioviale (1885-1949) and Silvio Ranieri (1882-1956).[46][92]

Antonio Vivaldi composed a mandolin concerto (Concerto in C major Op.3 6) and two concertos for two mandolins and orchestra. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart placed it in his 1787 work Don Giovanni and Beethoven created four variations of it. Antonio Maria Bononcini composed La conquista delle Spagne di Scipione Africano il giovane in 1707 and George Frideric Handel composed Alexander Balus in 1748. Others include Giovani Battista Gervasio (Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo), Giuseppe Giuliano (Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo), Emanuele Barbella (Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo), Domenico Scarlatti (Sonata n.54 (K.89) in D minor for Mandolin and Basso Continuo), and Addiego Guerra (Sonata in G major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo).[46][93]

More contemporary composers for the mandolin include Giuseppe Anedda (a virtuoso performer and teacher of the first chair of the Conservatory of Italian mandolin), Carlo Aonzo and Dorina Frati.

Japan

Instruments of the mandolin family are popular in Japan, particularly Neapolitan (round-back) style instruments, and Roman-Embergher style mandolins are still being made there.[94] Japan became seriously interested in mandolins at the beginning of the 20th Century during a process of becoming westernized.[95]

Where interest in the mandolin declined in the United States and parts of Europe after World War I, in Japan there was a boom, with orchestras being formed all over the country.[95]

Connections to the West, including cultural connections with World War II ally Italy, were forming. One musical connection which encouraged mandolin music growth was a visit by mandolin virtuoso Raffaele Calace, who toured extensively at the end of 1924, into 1925, and who gave a performance for the Japanese emperor. Another visiting mandolin virtuoso, Samuel Adelstein, toured from his home in the United States.

The expansion of mandolin use continued after World War II through the late 1960s, and Japan still maintains a strong classical music tradition using mandolins, with active orchestras and university music programs. New orchestras were founded and new orchestral compositions composed. Japanese mandolin orchestras today may consist of up to 40 or 50 members, and can include woodwind, percussion, and brass sections. Japan also maintains an extensive collection of 20th Century mandolin music from Europe and one of the most complete collections of mandolin magazines from mandolin's golden age, purchased by Morishige Takei.

Morishige Takei (1890–1949), who studied Italian at Tokyo College of Language and was a member of the court of Emperor Hirohito, established the mandolin orchestra in the Italian style before World War II. He was also a major composer, with 114 compositions for mandolin.

The military government could not persecute Japanese mandolinists by the authority of Takei[citation needed] So the Japanese mandolin orchestras continued to perform old Italian works after World War II, and they are prosperous today.

Another composer, Jiro Nakano (1902–2000), arranged many of the Italian works for regular orchestras or winds composed before World War II as new repertoires for Japanese mandolin orchestras.

Original compositions for mandolin orchestras were composed increasingly after World War II. Seiichi Suzuki (1901–1980) composed music for early Kurosawa films. Others include Tadashi Hattori (1908–2008), and Hiroshi Ohguri (1918–1982). Ohguri was influenced by Béla Bartók and composed many symphonic works for Japanese mandolin orchestras. Yasuo Kuwahara (1946–2003) used German techniques. Many of his works were published in Germany.

New Zealand

The Auckland Mandolinata mandolin orchestra was formed in 1969 by Doris Flameling (1932–2004). Soon after arriving from the Netherlands with her family, Doris started teaching guitar and mandolin in West Auckland. In 1969, she formed a small ensemble for her pupils. This ensemble eventually developed into a full size mandolin orchestra, which survives today. Doris was the musical director and conductor of this orchestra for many years. The orchestra is currently led by Bryan Holden (conductor).

The early history of the mandolin in New Zealand is currently being researched by members of the Auckland Mandolinata.

Portugal

The bandolim (Portuguese for "mandolin") was a favourite instrument within the Portuguese bourgeoisie of the 19th century, but its rapid spread took it to other places, joining other instruments. Today you can see mandolins as part of the traditional and folk culture of Portuguese singing groups and the majority of the mandolin scene in Portugal is in Madeira Island. Madeira has over 17 active mandolin Orchestras and Tunas. The mandolin virtuoso Fabio Machado is one of Portugal's most accomplished mandolin players. The Portuguese influence brought the mandolin to Brazil.

Romania

South Africa

Mandolin has been a prominent instrument in the recordings of Johnny Clegg and his bands Juluka and Savuka. Since 1992, Andy Innes has been the mandolinist for Johnny Clegg and Savuka.

Sri Lanka

The mandolin was brought to Sri Lanka by the Portuguese, who colonized Sri Lanka from 1505-1658. The instrument has been heavily used in baila, a genre of Sri Lankan music which formed from a mixture of Portuguese, African and Sinhala music. For example, the mandolin features prominently in M.S. Fernando's baila song, "Bola Bola Meti".

Turkey

Turkey has been the home of a mandolin-banjo manufacturer, Cümbüs, since the early 20th century. The country had what was claimed to be its first Mandolin festival in June 2015, and has at least one Mandolin Orchestra.[96][97]

One professional musician to use the mandolin is Sumru Ağıryürüyen who is known for singing and playing many styles of music including world music, Klezmer, Turkish folk, Balkan folk, blues, jazz, krautrock, protest rock and maqam.[98][99]

United Kingdom

The mandolin has been used extensively in the traditional music of England and Scotland for generations. Simon Mayor is a prominent British player who has produced six solo albums, instructional books and DVDs, as well as recordings with his mandolin quartet the Mandolinquents. The instrument has also found its way into British rock music. The mandolin was played by Mike Oldfield (and introduced by Vivian Stanshall) on Oldfield's album Tubular Bells, as well as on a number of his subsequent albums (particularly prominently on Hergest Ridge (1974) and Ommadawn (1975)). It was used extensively by the British folk-rock band Lindisfarne, who featured two members on the instrument, Ray Jackson and Simon Cowe, and whose "Fog on the Tyne" was the biggest selling UK album of 1971-1972. The instrument was also used extensively in the UK folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s with bands such as Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span taking it on as the lead instrument in many of their songs. Maggie May by Rod Stewart, which hit No. 1 on both the British charts and the Billboard Hot 100, also featured Jackson's playing. It has also been used by other British rock musicians. Led Zeppelin's bassist John Paul Jones is an accomplished mandolin player and has recorded numerous songs on mandolin including Going to California and That's the Way; the mandolin part on The Battle of Evermore is played by Jimmy Page, who composed the song. Other Led Zeppelin songs featuring mandolin are Hey Hey What Can I Do, and Black Country Woman. Pete Townshend of The Who played mandolin on the track Mike Post Theme, along with many other tracks on Endless Wire. McGuinness Flint, for whom Graham Lyle played the mandolin on their most successful single, When I'm Dead And Gone, is another example. Lyle was also briefly a member of Ronnie Lane's Slim Chance, and played mandolin on their hit How Come. One of the more prominent early mandolin players in popular music was Robin Williamson in The Incredible String Band. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull is a highly accomplished mandolin player (beautiful track Pussy Willow), as is his guitarist Martin Barre. The popular song Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want by The Smiths featured a mandolin solo played by Johnny Marr. More recently, the Glasgow-based band Sons and Daughters featured the mandolin, played by Ailidh Lennon, on tracks such as Fight, Start to End, and Medicine. British folk-punk icons the Levellers also regularly use the mandolin in their songs. Current bands are also beginning to use the Mandolin and its unique sound - such as South London's Indigo Moss who use it throughout their recordings and live gigs. The mandolin has also featured in the playing of Matthew Bellamy in the rock band Muse. It also forms the basis of Paul McCartney's 2007 hit "Dance Tonight." That was not the first time a Beatle played a mandolin, however; that distinction goes to George Harrison on Gone Troppo, the title cut from the 1982 album of the same name. The mandolin is taught in Lanarkshire by the Lanarkshire Guitar and Mandolin Association to over 100 people. Also more recently hard rock supergroup Them Crooked Vultures have been playing a song based primarily using a mandolin. This song was left off their debut album, and features former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones.[citation needed]

In the Classical style, performers such as Hugo D'Alton, Alison Stephens and Michael Hooper have continued to play music by British composers such as Michael Finnissy, James Humberstone and Elspeth Brooke.

United States

- See American mandolinists, American bluegrass mandolinists, Canadian mandolinists, and Canadian bluegrass mandolinists

Mandolin orchestras and classical-music virtuosos

The mandolin's popularity in the United States was spurred by the success of a group of touring young European musicians known as the Estudiantina Figaro, or in the United States, simply the "Spanish Students."[101] The group landed in the U.S. on January 2, 1880 in New York City, and played in Boston and New York to wildly enthusiastic crowds.[102] Ironically, this ensemble did not play mandolins but rather bandurrias, which are also small, double-strung instruments that resemble the mandolin.[103] The success of the Figaro Spanish Students spawned other groups who imitated their musical style and costumes.[102] An Italian musician, Carlo Curti, hastily started a musical ensemble after seeing the Figaro Spanish Students perform; his group of Italian born Americans called themselves the "Original Spanish Students," counting on the American public to not know the difference between the Spanish bandurrias and Italian mandolins.[102][104] The imitators' use of mandolins helped to generate enormous public interest in an instrument previously relatively unknown in the United States.[84][102]

Mandolin awareness in the United States blossomed in the 1880s, as the instrument became part of a fad that continued into the mid-1920s.[42][43][44] According to Clarence L. Partee, the first mandolin made in the United States was made in 1883 or 1884 by Joseph Bohmann, who was an established maker of violins in Chicago.[106] Partee characterized the early instrument as being larger than the European instruments he was used to, with a "peculiar shape" and "crude construction," and said that the quality improved, until American instruments were "superior" to imported instruments.[106] At the time, Partee was using an imported French-made mandolin.[106]

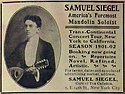

Instruments were marketed by teacher-dealers, much as the title character in the popular musical The Music Man.[107] Often, these teacher-dealers conducted mandolin orchestras: groups of 4-50 musicians who played various mandolin family instruments. However, alongside the teacher-dealers were serious musicians, working to create a spot for the instrument in classical music, ragtime and jazz. Like the teacher-dealers, they traveled the U.S., recording records, giving performances and teaching individuals and mandolin orchestras. Samuel Siegel played mandolin in Vaudeville and became one of America's preeminent mandolinists.[108] Seth Weeks was an African American who not only taught and performed in the United States, but also in Europe, where he recorded records.[109][110] Another pioneering African American musician and director who made his start with a mandolin orchestra was composer James Reese Europe. W. Eugene Page toured the country with a group, and was well known for his mandolin and mandola performances.[111][112] Other names include Valentine Abt, Samuel Adelstein, William Place, Jr., and Aubrey Stauffer.[108]

The instrument was primarily used in an ensemble setting well into the 1930s, and although the fad died out at the beginning of the 1930s, the instruments that were developed for the orchestra found a new home in bluegrass. The famous Lloyd Loar Master Model from Gibson (1923) was designed to boost the flagging interest in mandolin ensembles, with little success. However, The "Loar" became the defining instrument of bluegrass music when Bill Monroe purchased F-5 S/N 73987[113] in a Florida barbershop in 1943 and popularized it as his main instrument.

The mandolin orchestras never completely went away, however. In fact, along with all the other musical forms the mandolin is involved with, the mandolin ensemble (groups usually arranged like the string section of a modern symphony orchestra, with first mandolins, second mandolins, mandolas, mandocellos, mando-basses, and guitars, and sometimes supplemented by other instruments) continues to grow in popularity. Since the mid-nineties, several public-school mandolin-based guitar programs have blossomed around the country, including Fretworks Mandolin and Guitar Orchestra, the first of its kind. The national organization, Classical Mandolin Society of America, founded by Norman Levine, represents these groups. Prominent modern mandolinists and composers for mandolin in the classical music tradition include Samuel Firstman, Howard Fry, Rudy Cipolla, Dave Apollon, Neil Gladd, Evan Marshall, Marilynn Mair and Mark Davis (the Mair-Davis Duo), Brian Israel, David Evans, Emanuil Shynkman, Radim Zenkl, David Del Tredici and Ernst Krenek.[114]

Bluegrass, Blues, and the jug band

When Cowan Powers and his family recorded their old-time music from 1924-1926, his daughter Orpha Powers was one of the earliest known southern-music artists to record with the mandolin.[115] By the 1930s, single mandolins were becoming more commonly used in southern string band music, most notably by brother duets such as the sedate Blue Sky Boys (Bill Bolick and Earl Bolick) and the more hard-driving Monroe Brothers (Bill Monroe and Charlie Monroe). However, the mandolin's modern popularity in country music can be directly traced to one man: Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass music. After the Monroe Brothers broke up in 1939, Bill Monroe formed his own group, after a brief time called the Blue Grass Boys, and completed the transition of mandolin styles from a "parlor" sound typical of brother duets to the modern "bluegrass" style. He joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1939 and its powerful clear-channel broadcast signal on WSM-AM spread his style throughout the South, directly inspiring many musicians to take up the mandolin. Monroe famously played Gibson F-5 mandolin, signed and dated July 9, 1923, by Lloyd Loar, chief acoustic engineer at Gibson. The F-5 has since become the most imitated tonally and aesthetically by modern builders.

Monroe's style involved playing lead melodies in the style of a fiddler, and also a percussive chording sound referred to as "the chop" for the sound made by the quickly struck and muted strings. He also perfected a sparse, percussive blues style, especially up the neck in keys that had not been used much in country music, notably B and E. He emphasized a powerful, syncopated right hand at the expense of left-hand virtuosity. Monroe's most influential follower of the second generation is Frank Wakefield and nowadays Mike Compton of the Nashville Bluegrass Band and David Long, who often tour as a duet. Tiny Moore of the Texas Playboys developed an electric five-string mandolin and helped popularize the instrument in Western Swing music.[116]

Other major bluegrass mandolinists who emerged in the early 1950s and are still active include Jesse McReynolds (of Jim and Jesse) who invented a syncopated banjo-roll-like style called crosspicking—and Bobby Osborne of the Osborne Brothers, who is a master of clarity and sparkling single-note runs. Highly respected and influential modern bluegrass players include Herschel Sizemore, Doyle Lawson, and the multi-genre Sam Bush, who is equally at home with old-time fiddle tunes, rock, reggae, and jazz. Ronnie McCoury of the Del McCoury Band has won numerous awards for his Monroe-influenced playing. The late John Duffey of the original Country Gentlemen and later the Seldom Scene did much to popularize the bluegrass mandolin among folk and urban audiences, especially on the east coast and in the Washington, D.C. area.

Jethro Burns, best known as half of the comedy duo Homer and Jethro, was also the first important jazz mandolinist. Tiny Moore popularized the mandolin in Western swing music. He initially played an 8-string Gibson but switched after 1952 to a 5-string solidbody electric instrument built by Paul Bigsby. Modern players David Grisman, Sam Bush, and Mike Marshall, among others, have worked since the early 1970s to demonstrate the mandolin's versatility for all styles of music. Chris Thile of California is a well-known player, and has accomplished many feats of traditional bluegrass, classical, contemporary pop and rock; the band Nickel Creek featured his playing in its blend of traditional and pop styles, and he now plays in his band Punch Brothers. Most commonly associated with bluegrass, mandolin has been used a lot in country music over the years. Some well-known players include Marty Stuart, Vince Gill, and Ricky Skaggs.

Mandolin has also been used in blues music, most notably by Ry Cooder, who performed outstanding covers on his very first recordings, Yank Rachell, Johnny "Man" Young, Carl Martin, and Gerry Hundt. Howard Armstrong, who is famous for blues violin, got his start with his father's mandolin and played in string bands similar to the other Tennessee string bands he came into contact with, with band makeup including "mandolins and fiddles and guitars and banjos.[118] And once in a while they would ease a little ukulele in there and a bass fiddle." Other blues players from the era's string bands include Willie Black (Whistler And His Jug Band), Dink Brister, Jim Hill, Charles Johnson, Coley Jones (Dallas String Band), Bobby Leecan (Need More Band), Alfred Martin, Charlie McCoy (1909-1950), Al Miller, Matthew Prater, and Herb Quinn.[118]

It saw some use in jug band music, since that craze began as the mandolin fad was waning, and there were plenty of instruments available at relatively low cost.

Rock and Celtic

The mandolin has been used occasionally in rock music, first appearing in the psychedelic era of the late 1960s. Levon Helm of The Band occasionally moved from his drum kit to play mandolin, most notably on Rag Mama Rag, Rockin' Chair, and Evangeline. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull played mandolin on Fat Man, from their second album, Stand Up, and also occasionally on later releases. Rod Stewart's 1971 No. 1 hit Maggie May features a significant mandolin riff. David Grisman played mandolin on two Grateful Dead songs on the American Beauty album, Friend of the Devil and Ripple, which became instant favorites among amateur pickers at jam sessions and campground gatherings. John Paul Jones and Jimmy Page both played mandolin on Led Zeppelin songs. The popular alt rock group Imagine Dragons feature the mandolin on a few of their songs, most prominently being It's Time. Dash Crofts of the soft rock duo Seals and Crofts extensively used mandolin in their repertoire during the 1970s. Styx released the song Boat on the River in 1980, which featured Tommy Shaw on vocals and mandolin. The song didn't chart in the United States but was popular in much of Europe and the Philippines.

Some rock musicians today use mandolins, often single-stringed electric models rather than double-stringed acoustic mandolins. One example is Tim Brennan of the Irish-American punk rock band Dropkick Murphys. In addition to electric guitar, bass, and drums, the band uses several instruments associated with traditional Celtic music, including mandolin, tin whistle, and Great Highland bagpipes. The band explains that these instruments accentuate the growling sound they favor. The 1991 R.E.M. hit "Losing My Religion" was driven by a few simple mandolin licks played by guitarist Peter Buck, who also played the mandolin in nearly a dozen other songs. The single peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart (#1 on the rock and alternative charts),[119] Luther Dickinson of North Mississippi Allstars and The Black Crowes has made frequent use of the mandolin, most notably on the Black Crowes song "Locust Street." Armenian American rock group System of A Down makes extensive use of the mandolin on their 2005 double album Mezmerize/Hypnotize. Pop punk band Green Day has used a mandolin in several occasions, especially on their 2000 album, Warning. Boyd Tinsley, violin player of the Dave Matthews Band has been using an electric mandolin since 2005. Frontman Colin Meloy and guitarist Chris Funk of The Decemberists regularly employ the mandolin in the band's music. Nancy Wilson, rhythm guitarist of Heart, uses a mandolin in Heart's song "Dream of the Archer" from the album Little Queen, as well as in Heart's cover of Led Zeppelin's song "The Battle of Evermore." "Show Me Heaven" by Maria McKee, the theme song to the film Days of Thunder, prominently features a mandolin.

Many folk punk bands will also feature the mandolin. One such band is Days N' Daze, who make use of the mandolin, banjo, ukulele, as well as several other acoustic plucked string instruments. Other folk punk acts include Blackbird Raum, and Johnny Hobo and the Freight Trains.

Venezuela

As in Brazil, the mandolin has played an important role in the Music of Venezuela. It has enjoyed a privileged position as the main melodic instrument in several different regions of the country. Specifically, the eastern states of Sucre, Nueva Esparta, Anzoategui and Monagas have made the mandolin the main instrument in their versions of Joropo as well as Puntos, Jotas, Polos, Fulias, Merengues and Malagueñas. Also, in the west of the country the sound of the mandolin is intrinsically associated with the regional genres of the Venezuelan Andes: Bambucos, Pasillos, Pasodobles, and Waltzes. In the western city of Maracaibo the Mandolin has been played in Decimas, Danzas and Contradanzas Zulianas; in the capital, Caracas, the Merengue Rucaneao, Pasodobles and Waltzes have also been played with mandolin for almost a century. Today, Venezuelan mandolists include an important group of virtuoso players and ensembles such as Alberto Valderrama, Jesus Rengel, Ricardo Sandoval, Saul Vera, and Cristobal Soto.

Notable literature

Art or "classical" music

The tradition of so-called "classical music" for the mandolin has been somewhat spotty, due to its being widely perceived as a "folk" instrument. Significant composers did write music specifically for the mandolin, but few large works were composed for it by the most widely regarded composers. The total number of works these works is rather small in comparison to—say—those composed for violin. One result of this dearth being that there were few positions for mandolinists in regular orchestras.

Beethoven composed mandolin music[120] and enjoyed playing the mandolin.[121] His 4 small pieces date from 1796: Sonatine WoO 43a; Adagio ma non troppo WoO 43b; Sonatine WoO 44a and Andante con Variazioni WoO 44b.

The opera Don Giovanni by Mozart includes mandolin parts, including the accompaniment to the famous aria Deh vieni alla finestra, and Verdi's opera Otello calls for guzla accompaniment in the aria Dove guardi splendono raggi, but the part is commonly performed on mandolin.[122]

Vivaldi created a concerto for mandolin (Concerto in C major Op.3 # 6) and two concertos for mandolins and orchestra: one for mandolin, string bass & continuous in C major, (RV 425), and one for two mandolins, bass strings & continuous in G major, (RV 532).

Gustav Mahler used the mandolin in his Symphony No. 7, Symphony No. 8 and Das Lied von der Erde.

Parts for mandolin are included in works by Schoenberg (Variations op. 31), Stravinsky (Agon), Prokofiev (Romeo and Juliet) and Webern (opus Parts 10)

Some 20th century composers also used the mandolin as their instrument of choice (amongst these are: Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky and Prokofiev).

Among the most important European mandolin composers of the 20th century are Raffaele Calace (composer, performer and luthier) and Giuseppe Anedda (virtuoso concert pianist and professor of the first chair of the Conservatory of Italian Mandolin, Padua, 1975). Today representatives of Italian classical music and Italian classical-contemporary music include Ugo Orlandi, Carlo Aonzo, Dorina Frati, Mauro Squillante and Duilio Galfetti.

Japanese composers also produced orchestral music for mandolin in the 20th century, but these are not well known outside Japan.[citation needed]

To fill this gap in the literature, mandolin orchestras have traditionally played many arrangements of music written for regular orchestras or other ensembles. Some players have sought out contemporary composers to solicit new works. Traditional mandolin orchestras remain especially popular in Japan and Germany, but also exist throughout the United States, Europe and the rest of the world. They perform works composed for mandolin family instruments, or re-orchestrations of traditional pieces. The structure of a contemporary traditional mandolin orchestra consists of: first and second mandolins, mandolas (either octave mandolas, tuned an octave below the mandolin, or tenor mandolas, tuned like the viola), mandocellos (tuned like the cello), and bass instruments (conventional string bass or, rarely, mandobasses). Smaller ensembles, such as quartets composed of two mandolins, mandola, and mandocello, may also be found.

Unaccompanied solo

Accompaniment with solo

Duo

Concerto

Mandolin in the orchestra

See also

References

- ^ Dave Hynds. "Mandolins: A Brief History". mandolinluthier.com. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary, by Sibyl Marcuse (Corrected Edition 1975)

- ^ a b The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and others (2001)

- ^ Campen, Ank van. "The music-bow from prehistory till today". HarpHistory.info. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Trois Freres Cave". Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ Dumbrill, 1998 & page 179, 231, 235-236, 308-310

- ^ Dumbrill, 1998 & page 308-310

- ^ a b Dumbrill, 1998 & page 321

- ^ http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1447477&partId=1&people=24615&peoA=24615-3-17&page=1 British Museum, Cylinder Seal, Culture/period Uruk, Date 3100BC (circa1), Museum number 41632.

- ^ Dumbrill, 1998 & page 310

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Iranica - Barbat". Iranicaonline.org. 1988-12-15. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Kasidah. "Pakistan, Swat Valley, Gandhara region Lute Player; From a group of Five Celestial Musicians, 4th-5th century Sculpture; Stone, Gray schist, 10 1/8 x 4 3/4 x 2 1/2 in. (25.7 x 12.1 x 6.4 cm)". Pinterest.com. Retrieved March 25, 2015. Musician playing a 4th-to-5th-Century lute, excavated in Gandhara, and part of a Los Angeles County Art Museum collection of Five Celestial Musicians

- ^ "Bracket with two musicians 100s, Pakistan, Gandhara, probably Butkara in Swat, Kushan Period (1st century-320)". The Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ https://m.flickr.com/#/photos/julio-claudians/8098646683/ Flicker based photo of the museum information sign for the stele.

- ^ a b c "Encyclopaedia Iranica - Barbat". Iranicaonline.org. 1988-12-15. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ^ Menocal, María Rosa, Raymond P. Scheindlin, Michael Anthony Sells (eds.) (2000), The Literature of Al-Andalus, Cambridge University Press

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gill, John (2008). Andalucia: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-01-95-37610-4.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira M. (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780521779333.

- ^ Davila, Carl (2009), Fixing a Misbegotten Biography: Ziryab in the Mediterranean World, Al-Masaq: Islam in the Medieval Mediterranean Vol. 21 No. 2

- ^ a b Colin Lawson and Robin Stowell, The Cambridge History of Musical Performance, Cambridge University Press, Feb 16, 2012

- ^ Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship, Manchester University Press, 1977, p. 70-71.

- ^ J.W. McKinnon "Pandoura" in New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments Vol 3 p 10 ed S. Sadie (Macmillan Press, London 1984).

- ^ Sparks 2003, p. 218

- ^ "Biography of Antonio Vinaccia". Amati.com. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Biography of Gennaro Vinaccia". Amati.com. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Neapolitan mandolin". Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Neapolitan mandolin". Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b Tyler & Sparks 1996

- ^ a b c d Sparks 2003, p. 15–16

- ^ "Information on Pasquale Vinaccia, violin maker in Naples, Italy". amati.com. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "The Bickford mandolin method". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ The Embergher mandolin, Ralf Leenen and Barry Pratt, 2004. ISBN 9073838312, 9789073838314

- ^ Sparks 2003

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 15

- ^ Sparks 2003, p. 1, 9–10, 14–15

- ^ Sparks 2003, p. 1

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 1–3

- ^ Biaggi, G. A. (March 20, 1875). "The Lute and the Mandolin, with some remarks on Sig. Giovanni Vailati in connection with them (reprint from La Gazetta Musicale in Milan)". The Musical World. Vol. 53, no. 12. London: William Duncan Davison. pp. 204–205. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

Though the instrument is entirely out of fashion, the house of Ricordi published last year [1874] at Milan A Metodo per Mandolino, a well planned work, well carried out, by Sic. Carmine De-Laurentiis.

- ^ Salvador Léonardi, Méthode pour Banjoline ou Mandoline-Banjo, Paris, 1921

- ^ Sparks 2003, p. 21

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 20–29

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 22–135

- ^ a b c Sparks 2003, p. 96

- ^ a b The Classical Mandolin Society, Classical Mandolin - A (Very) Brief Overview

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 153–154

- ^ a b c Ian Pommerenke, The Mandolin in the early to mid 19th Century, Lanarkshire Guitar and Mandolin Association Newsletter, Spring 2007.

- ^ Roger Vetter. "Mandolin - Neapolitan". Grinnell College Musical Instrument Collection. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Roger Vetter. "Mandolin - flat-back". Grinnell College Musical Instrument Collection. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

a newly developed resonator design pioneered by the Gibson Company with arched top and back boards with f-shaped soundholes, like violin resonators

- ^ "OM floating bridge?". Mandolin Cafe. April 20, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ McDonald 2008, p. 1

- ^ "Mandoline". Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. 17. 1911.

- ^ "Radiused vs. flat fingerboard on mandolin?". May 3, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Siminoff, Roger H. (2002). The Luthier's Handbook. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-634-01468-0.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ruppa, Paul; American Mando-Bass History 101

- ^ Marcuse, Sibyl; Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary; W. W. Norton & Company (1975). (see entries for mandolin, and for individual mandolin family members.)

- ^ Johnson, J. R.; The Mandolin Orchestra in America, Part 3: Other Instruments, American Lutherie, No. 21 (Spring) 1990, pp.45-46.

- ^ Tyler & Sparks 1989

- ^ a b c d e f "Who are the top classical builders? [Archive] - Mandolin Cafe Forum". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Sparks 2003, p. 37–38

- ^ a b c d "Mandolin Glossary". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Milanese Mandolin Makers". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Sparks 2003, p. 206

- ^ a b c d e Adelstein, 1893 & page 14

- ^ a b "Thread: Plans of Brescian mandolin..." Mandolin Cafe. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Bortolazzi, Bartolomeo (1805). Anweisung die Mandoline von selbst zu erlernen nebst einigen Uebungsstucken von Bortolazzi (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Breitkopf and Härtell. p. 1.

- ^ a b Sparks 2003, p. 205

- ^ Labraid Mandolins

- ^ Labraid Mandolins. Grand Concert - Brian Dean.

- ^ "Mandolin (neapolitan, Round Back, Bowl Back...)". Forums. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Japanese Mandolin Makers". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Philip J. Bone (1914). The guitar and mandolin, Biographies of celebrated players and composers for these instruments. London: Schott and Company.

- ^ a b c McDonald, 2008 & page 16

- ^ a b McDonald, 2008 & page 18

- ^ Stefan Sobell Guitars[1]

- ^ McDonald, 2008 & page 30

- ^ a b c "Thread: Avi Avital and the Arik Kerman mandolin". mandolincafe.com. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

This thread digressed into the topic of Avi's Kerman, where it was established that it has a double top and a convex back.", "...it looks like it is based on the modern German flatback asmade by makers such as Seifert, a little deep-bodied. The difference from the German models is that it has the sound holes on the edges and, even more important(?) has a double top

- ^ a b Artist To Artist: 10 Minutes With Avi Avital. The Bluegrass Special, January 2011 by Joe Brent.

- ^ a b "Alon Sariel interview". Mandolin.org.uk. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

What mandolins do you own? Which one(s) is(are) your favourite(s)? Whoever knows the Beer-Sheva school of mandolin must have heard of the Israeli type of modern mandolins. A mandolin maker called Arik Kerman who lives in Tel-Aviv, invented a formula to make the mandolin in a way for which it has a much of a round and sweet sound, and can easily produce a very soft sound other than the metallic Neapolitan one...

- ^ a b Instrumentarium - Alon Sariel.

- ^ a b "Concert artists: Tom Cohen". frusion.co.uk. Retrieved September 3, 2015.