Mauthausen concentration camp

48°15′25″N 14°30′04″E / 48.25694°N 14.50111°E

| Mauthausen-Gusen | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

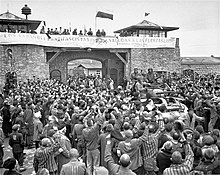

Gate to the garage yard in the Mauthausen concentration camp | |

| Other names | Mauthausen, Gusen |

| Location | in and around Mauthausen and Gusen, Upper Austria |

| Operated by | DEST cartel and the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) Soviet Red Army (after World War II) |

| Commandant | Franz Ziereis |

| Operational | August 1938 – May 1945 |

| Number of inmates | mainly Soviet and Polish citizens |

| Killed | between 122,766 and 320,000 (estimated) |

| Liberated by | US Army, May 1945 |

Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp was the hub of a large group of German concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Sankt Georgen an der Gusen (Gusen) in Upper Austria, roughly 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of the city of Linz. The camp operated from the time of the Anschluss, when Austria was annexed into the German Third Reich in early 1938, to the beginning of May 1945, at the end of the Second World War. Starting with a single camp at Mauthausen, the complex expanded over time and by the summer of 1940 Mauthausen had become one of the largest labour camp complexes in the German-controlled part of Europe, with four main subcamps at Mauthausen and nearby Gusen, and nearly 100 other subcamps located throughout Austria and southern Germany, directed from a central office at Mauthausen.[1][2]

As at other Nazi concentration camps, the inmates at Mauthausen-Gusen were forced to work as slave labour, under conditions that caused many deaths. The subcamps of the Mauthausen complex included quarries, munitions factories, mines, arms factories and plants assembling Me 262 fighter aircraft.[3][4] In January 1945, the camps contained roughly 85,000 inmates.[5] The death toll remains unknown, although most sources place it between 122,766 and 320,000 for the entire complex.

The Mauthausen-Gusen camp was one of the first massive concentration camp complexes in Nazi Germany, and the last to be liberated by the Allies. The two main camps, Mauthausen and Gusen I, were labelled as "Grade III" (Stufe III) camps, which meant that they were intended to be the toughest camps for the "Incorrigible political enemies of the Reich".[6] Mauthausen never lost this Stufe III classification.[6] In the offices of the Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt; RSHA) it was referred to by the nickname Knochenmühle – the bone-grinder (literally bone-mill).[6] Unlike many other concentration camps, which were intended for all categories of prisoners, Mauthausen was mostly used for extermination through labour of the intelligentsia – educated people and members of the higher social classes in countries subjugated by the Nazi regime during World War II.[7][8] The main camp of the complex in Mauthausen is now a museum.

History

KL Mauthausen

On 9 August 1938, prisoners from Dachau concentration camp near Munich were sent to the town of Mauthausen in Austria, to begin the construction of a new slave labour camp.[9] The site was chosen because of the nearby granite quarry, and its proximity to Linz.[5][10] Although the camp was controlled by the German state from the beginning, it was founded by a private company as an economic enterprise.[10] The owner of the Wiener-Graben quarry (the Marbacher-Bruch and Bettelberg quarries) was a DEST Company: an acronym for Deutsche Erd– und Steinwerke GmbH.[11] The company was led by Oswald Pohl, who was a high-ranking official of the Schutzstaffel (SS).[12] It rented the quarries from the City of Vienna in 1938 and started the construction of the Mauthausen camp.[3] A year later, the company ordered the construction of the first camp at Gusen. The granite mined in the quarries had previously been used to pave the streets of Vienna, but the Nazi authorities envisioned a complete reconstruction of major German towns in accordance with plans of Albert Speer and other proponents of Nazi architecture,[13] for which large quantities of granite were needed.[10] The money to fund the construction of the Mauthausen camp was gathered from a variety of sources, including commercial loans from Dresdner Bank and Prague-based Escompte Bank; the so-called Reinhardt's fund (meaning money stolen from the inmates of the concentration camps themselves); and from the German Red Cross.[5][note 1]

Mauthausen initially served as a strictly-run prison camp for common criminals, prostitutes[14] and other categories of "Incorrigible Law Offenders".[note 2] On 8 May 1939 it was converted to a labour camp which was mainly used for the incarceration of political prisoners.[16]

KL Gusen

"(...) In March 1940 I was brought to Mauthausen to build the Gusen camp. The building tempo had to be accelerated, because the "Aktion gegen die polnische Intelligenz" was designated for the month of April. What no one knew in the home country, we knew – the SS-men who were beating us, told us that we build a camp for our rotten brothers from Poland, who today can still spend Easter uneventfully, without an inkling what awaits them. They called the camp under construction Gusen "Vernichtungslager fur die polnische Intelligenz"". — Stefan Józefowicz, bank headmaster, no. 1129 in Mauthausen, 43069 Gusen.[17]

DEST began purchasing land at Gusen in May 1938. During 1938 and 1939, inmates of the nearby Mauthausen makeshift camp marched daily to the granite quarries at Gusen, which were more productive and more important for DEST than the Wienergraben Quarry.[3] After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the as-yet unfinished Mauthausen camp was already overcrowded with prisoners. The numbers of inmates rose from 1,080 in late 1938 to over 3,000 a year later.[18][19] At about that time, the construction of a new camp "for the Poles" began in Gusen (48°15′26″N 14°27′48″E / 48.25722°N 14.46333°E), about 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) away. The new camp (later named Gusen I) became operational in May 1940. The first inmates were put in the first two huts (No. 7 and 8) on 17 April 1940,[20] while the first transport of prisoners – mostly from the camps in Dachau and Sachsenhausen – arrived just over a month later, on 25 May.[21]

Like nearby Mauthausen, the Gusen camp also rented inmates out to various local businesses as slave labour. In October 1941, several huts were separated from the Gusen subcamp by barbed wire and turned into a separate Prisoner of War Labour Camp (German: Kriegsgefangenenarbeitslager).[22][23] This camp had many prisoners of war, mostly Soviet officers.[24][23] By 1942 the production capacity of both Mauthausen and Gusen had reached its peak. Gusen was expanded to include the central depot of the SS, where various goods, which had been seized from occupied territories, were sorted and then dispatched to Germany.[25] Local quarries and businesses were in constant need of a new source of labour as more and more Austrians were drafted into the Wehrmacht.[26]

In March 1944, the former SS depot was converted to a new subcamp, named Gusen II, which served as an improvised concentration camp until the end of the war. Gusen II contained about 12,000 to 17,000 inmates, who were deprived of even the most basic facilities.[1] In December 1944, another part of Gusen was opened in nearby Lungitz. Here, parts of a factory infrastructure were converted into the third subcamp of Gusen – Gusen III.[1] The rise in the number of subcamps could not catch up with the rising number of inmates, which led to overcrowding of the huts in all of the subcamps of Mauthausen-Gusen. From late 1940 to 1944, the number of inmates per bed rose from two to four.[1]

Camp system

As the production in all of the subcamps of Mauthausen-Gusen complex was constantly increasing, so were the numbers of detainees and subcamps themselves. Although initially the camps of Gusen and Mauthausen mostly served the local quarries, from 1942 onwards they began to be included in the German war machine. To accommodate the ever-growing number of slave workers, additional subcamps (German: Außenlager) of Mauthausen were built. By the end of the war, the list included 101 camps (including 49 major subcamps)[27] which covered most of modern Austria, from Mittersill south of Salzburg to Schwechat east of Vienna and from Passau on the pre-war Austro-German border to the Loibl Pass on the border with Yugoslavia. The subcamps were divided into several categories, depending on their main function: Produktionslager for factory workers, Baulager for construction, Aufräumlager for cleaning the rubble in Allied-bombed towns, and Kleinlager (small camps) where the inmates were working specifically for the SS.[citation needed]

Business enterprise

The production output of Mauthausen-Gusen exceeded that of each of the five other large slave labour centres: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Flossenbürg, Gross-Rosen, Marburg and Natzweiler-Struthof, in terms of both production quota and profits.[28] The list of companies using slave labour from the Mauthausen-Gusen camp system was long, and included both national corporations and small, local firms and communities. Some parts of the quarries were converted into a Mauser machine pistol assembly plant. In 1943, an underground factory for the Steyr-Daimler-Puch company was built in Gusen. Altogether, 45 larger companies took part in making Mauthausen-Gusen one of the most profitable concentration camps of Nazi Germany, with more than 11,000,000 Reichsmark[note 3] in profits in 1944 alone (EUR 86.7 million in 2024). The companies using slave laborers from Mauthausen included:[28]

- DEST cartel (producing bricks and quarrying stone for German state construction projects)

- Accumulatoren-Fabrik AFA (the main producer of batteries for German U-boats)

- Bayer (the main German producer of medicines and medications)

- Deutsche Bergwerks- und Hüttenbau (constructing mines and quarries)

- Linz-based Eisenwerke Oberdonau (the largest World War II steel supplier for the German Panzer tanks)[31]

- Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark (aeroplane engine manufacturer)

- Otto Eberhard Patronenfabrik (munitions works)

- Heinkel and Messerschmitt (Heinkel-Sud facilities in Floridsdorf, Vienna-Schwechat and Zwölfaxing, and other aeroplane factories, also a V-2 rocket factory)

- Österreichische Sauerwerks (arms producer)

- Rax-Werke (machinery and V-2 rockets)

- Steyr-Daimler-Puch (arms and vehicles)

- Universale Hoch und Tiefbau (construction of tunnels in the Loibl Pass)

Prisoners were also rented out as slave labour to work on local farms, road construction, reinforcing and repairing the banks of the Danube, and the construction of large residential areas in Sankt Georgen[3] as well as being forced to excavate archaeological sites in Spielberg.[citation needed]

When the Allied strategic bombing campaign started to target the German war industry, German planners decided to move production to underground facilities that were impenetrable to enemy aerial bombardment. In Gusen I, the prisoners were ordered to build several large tunnels beneath the hills surrounding the camp (code-named Kellerbau). By the end of World War II the prisoners had dug 29,400 square metres (316,000 sq ft) to house a small-arms factory. In January 1944, similar tunnels were also built beneath the village of Sankt Georgen by the inmates of Gusen II subcamp (code-named Bergkristall).[32] They dug roughly 50,000 square metres (540,000 sq ft) so the Messerschmitt company could build an assembly plant to produce the Messerschmitt Me 262 and V-2 rockets.[33] In addition to planes, some 7,000 square metres (75,000 sq ft) of Gusen II tunnels served as factories for various war materials.[3][34] In late 1944, roughly 11,000 of the Gusen I and II inmates were working in underground facilities.[35] An additional 6,500 worked on expanding the underground network of tunnels and halls. In 1945, the Me 262 works was already finished and the Germans were able to assemble 1,250 planes a month.[3][note 4] This was the second largest plane factory in Germany after the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, which was also underground.[35]

Weapons research

In January 2015, a "panel of archaeologists, historians and other experts" ruled out the earlier claims of an Austrian filmmaker that a bunker underneath the camp was connected to the German nuclear weapon project.[37] The panel indicated that stairs uncovered during an excavation prompted by the allegations led to an SS shooting range.[37]

Extermination through labour

The political function of the camp continued in parallel with its economic role. Until at least 1942, it was used for the imprisonment and murder of Germany's political and ideological enemies, both real and imagined.[2][38] The camp served the needs of the German war machine and also carried out extermination through labour. When the inmates were totally exhausted after having worked in the quarries for 12 hours a day, or if they were too ill or too weak to work, they were then transferred to the Revier ("Krankenrevier", sick barrack) or other places for extermination. Initially, the camp did not have a gas chamber of its own and the so-called Muselmänner, or prisoners who were too sick to work, after being maltreated, under-nourished or exhausted, were then transferred to other concentration camps for extermination (mostly to the infamous Hartheim Euthanasia Centre,[39] which was 40.7 kilometres or 25.3 miles away), or killed by lethal injection and cremated in the local crematorium. The growing number of prisoners made the system too expensive and from 1940, Mauthausen was one of the few camps in the West to use a gas chamber on a regular basis. In the beginning, an improvised mobile gas chamber – a van with the exhaust pipe connected to the inside – shuttled between Mauthausen and Gusen.[40] By December 1941, a permanent gas chamber that could kill about 120 prisoners at a time was completed.[41][42]

Inmates

Until early 1940, the largest group of inmates consisted of German, Austrian and Czechoslovak socialists, communists, homosexuals, anarchists and people of Romani origin. Other groups of people to be persecuted solely on religious grounds were the Sectarians, as they were dubbed by the Nazi regime, meaning Bible Students, or as they are called today, Jehovah's Witnesses. The reason for their imprisonment was their rejection of giving the loyalty oath to Hitler and their refusal to participate in any kind of military service.[16]

| Subcamp inmate counts Late 1944 – early 1945[5][note 5] | |

|---|---|

| Gusen (I, II and III combined) | 26,311 |

| Ebensee | 18,437 |

| Gunskirchen | 15,000 |

| Melk | 10,314 |

| Linz | 6,690 |

| Amstetten | 2,966 |

| Wiener-Neudorf | 2,954 |

| Schwechat | 2,568 |

| Steyr-Münichholz | 1,971 |

| Schlier-Redl-Zipf | 1,488 |

In early 1940, many Poles were transferred to the Mauthausen-Gusen complex. The first groups were mostly composed of artists, scientists, Boy Scouts, teachers, and university professors,[5][43] who were arrested during Intelligenzaktion and the course of the AB Action.[44] Camp Gusen II was called by Germans Vernichtungslager fur die polnische Intelligenz ("Extermination camp for Polish intelligentsia").[45]

Later in the war, new arrivals were from every category of the "unwanted", but educated people and so-called political prisoners constituted the largest part of all inmates until the end of the war. During World War II, large groups of Spanish Republicans were also transferred to Mauthausen and its subcamps. Most of them were former Republican soldiers or activists who had fled to France after Franco's victory and then were captured by German forces after the defeat of France in 1940 or handed over to the Germans by the Vichy authorities. The largest of these groups arrived at Gusen in January 1941.[46] In early 1941, almost all the Poles and Spaniards, except for a small group of specialists working in the quarry's stone mill, were transferred from Mauthausen to Gusen.[36] Following the outbreak of the Soviet-German War in 1941, the camps started to receive a large number of Soviet POWs. Most of them were kept in huts separated from the rest of the camp. The Soviet prisoners of war were a major part of the first groups to be gassed in the newly built gas chamber in early 1942. In 1944, a large group of Hungarian and Dutch Jews, about 8,000 people altogether, was also transferred to the camp. Much like all the other large groups of prisoners that were transferred to Mauthausen-Gusen, most of them either died as a result of the hard labour and poor conditions, or were deliberately killed.[citation needed]

After the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 and the outbreak of the partisan resistance in summer of the same year, many people suspected of aiding the Yugoslav resistance were sent to the Mauthausen camp, mostly from areas under direct German occupation, namely northern Slovenia and Serbia. An estimated 1,500 Slovenes died in Mauthausen.[47]

Throughout the years of World War II, the camps of Mauthausen-Gusen received new prisoners in smaller transports daily, mostly from other concentration camps in German-occupied Europe. Most of the prisoners at the subcamps of Mauthausen had been kept in a number of different detention sites before they arrived. The most notable of such centres for Mauthausen-Gusen were the infamous camps at Dachau and Auschwitz. The first transports from Auschwitz arrived in February 1942. The second transport in June of that year was much larger and numbered some 1,200 prisoners. Similar groups were sent from Auschwitz to Gusen and Mauthausen in April and November 1943, and then in January and February 1944. Finally, after Adolf Eichmann visited Mauthausen in May of that year, Mauthausen-Gusen received the first group of roughly 8,000 Hungarian Jews from Auschwitz; the first group to be evacuated from that camp before the Soviet advance. Initially, the groups evacuated from Auschwitz consisted of qualified workers for the ever-growing industry of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp complex, but as the evacuation proceeded other categories of people were also transported to Mauthausen, Gusen, Vienna or Melk.[citation needed]

Over time, Auschwitz had to almost stop accepting new prisoners and most were directed to Mauthausen instead. The last group – roughly 10,000 prisoners – was evacuated in the last wave in January 1945, only a few weeks before the Soviet liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex.[48] Among them was a large group of civilians arrested by the Germans after the failure of the Warsaw Uprising,[49][23] but by the liberation not more than 500 of them were still alive.[50] Altogether, during the final months of the war, 23,364 prisoners from other concentration camps arrived at the camp complex.[50] Many more perished from exhaustion during death marches, or in railway wagons, where the prisoners were confined at sub-zero temperatures for several days before their arrival, without adequate food or water. Prisoner transports were considered less important than other important services, and could be kept on sidings for days as other trains passed.[citation needed]

Many of those who survived the journey died before they could be registered, whilst others were given the camp numbers of prisoners who had already been killed.[50] Most were then accommodated in the camps or in the newly established tent camp (German: Zeltlager) just outside the Mauthausen subcamp, where roughly 2,000 people were forced into tents intended for not more than 800 inmates, and then starved to death.[51]

As in all other German concentration camps, not all the prisoners were equal. Their treatment depended largely on the category assigned to each inmate, as well as their nationality and rank within the system. The so-called kapos, or prisoners who had been recruited by their captors to police their fellow prisoners, were given more food and higher pay in the form of concentration camp coupons which could be exchanged for cigarettes in the canteen, as well as a separate room inside most barracks.[52] On Himmler's order of June 1941, a brothel was opened in the Mauthausen and Gusen I camps in 1942.[53][54] The Kapos formed the main part of the so-called Prominents (German: Prominenz), or prisoners who were given a much better treatment than the average inmate.[55]

Women and children in Mauthausen

Although the Mauthausen camp complex was mostly a labour camp for men, a women's camp was opened in Mauthausen, in September 1944, with the first transport of female prisoners from Auschwitz. Eventually, more women and children came to Mauthausen from Ravensbrück, Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Rosen, and Buchenwald. Along with the female prisoners came some female guards; twenty are known to have served in the Mauthausen camp, and sixty in the whole camp complex. Female guards also staffed the Mauthausen subcamps at Hirtenberg, Lenzing (the main women's subcamp in Austria), and Sankt Lambrecht. The Chief Overseers at Mauthausen were firstly Margarete Freinberger, and then Jane Bernigau. Almost all the female Overseers who served in Mauthausen were recruited from Austrian cities and towns between September and November 1944. In early April 1945, at least 2,500 more female prisoners came from the female subcamps at Amstetten, St. Lambrecht, Hirtenberg, and the Flossenbürg subcamp at Freiberg. According to Daniel Patrick Brown, Hildegard Lächert also served at Mauthausen.[56]

The available Mauthausen inmate statistics[57] from the spring of 1943, shows that there were 2,400 prisoners below the age of 20, which was 12.8% of the 18,655 population. By late March 1945, the number of juvenile prisoners in Mauthausen increased to 15,048, which was 19.1% of the 78,547 Mauthausen inmates. The number of imprisoned children increased 6.2 times, whereas the total number of adult prisoners during the same period multiplied by a factor of only four. These numbers reflected the increasing use of Polish, Czech, Russian, and Balkan teenagers as slave labour as the war continued.[58] Statistics showing the composition of juvenile inmates shortly before their liberation reveal the following major child/prisoner sub-groups: 5,809 foreign civilian labourers, 5,055 political prisoners, 3,654 Jews, and 330 Russian POWs. There were also 23 Romani children, 20 so-called "anti-social elements", six Spaniards, and three Jehovah's Witnesses.[57]

Treatment of inmates and methodology of crime

Mauthausen was not the only concentration camp where the German authorities implemented their extermination through labour (Vernichtung durch Arbeit) programme, but the regime at Mauthausen was one of the most brutal and severe. The conditions within the camp were considered exceptionally hard to bear, even by concentration camp standards.[59][60][61] The inmates suffered not only from malnutrition, overcrowded huts and constant abuse and beatings by the guards and kapos,[36] but also from exceptionally hard labour.[41] As there were too many prisoners in Mauthausen to have all of them work in its quarry at the same time, many were put to work in workshops, or had to do other manual work, whilst the unfortunate ones who were selected to work in the quarry were only there because of their so-called "crimes" in the camp. The reasons for sending them to work in the "punishment detail" were trivial, and included such "crimes" as not saluting a German passing by.[citation needed]

The work in the quarries – often in unbearable heat or in temperatures as low as −30 °C (−22 °F)[36] – led to exceptionally high mortality rates.[61][note 6] The food rations were limited, and during the 1940–1942 period, an average inmate weighed 40 kilograms (88 lb).[62] It is estimated that the average energy content of food rations dropped from about 1,750 calories (7,300 kJ) a day during the 1940–1942 period, to between 1,150 and 1,460 calories (4,800 and 6,100 kJ) a day during the next period. In 1945 the energy content was even lower and did not exceed 600 to 1,000 calories (2,500 to 4,200 kJ) a day – less than a third of the energy needed by an average worker in heavy industry.[1] The reduced rations led to the starvation of thousands of inmates.[citation needed]

The inmates of Mauthausen, Gusen I, and Gusen II had access to a separate part of the camp for the sick – the so-called Krankenlager. Despite the fact that (roughly) 100 medics from among the inmates were working there,[63] they were not given any medication and could offer only basic first aid.[5][63] Thus the hospital camp – as it was called by the German authorities – was, in fact, the last stop before death for thousands of inmates, and very few had a chance to recover.[citation needed]

The rock quarry in Mauthausen was at the base of the infamous "Stairs of Death". Prisoners were forced to carry roughly-hewn blocks of stone – often weighing as much as 50 kilograms (110 lb) – up the 186 stairs, one prisoner behind the other. As a result, many exhausted prisoners collapsed in front of the other prisoners in the line, and then fell on top of the other prisoners, creating a horrific domino effect; the first prisoner falling onto the next, and so on, all the way down the stairs.[64]

Such brutality was not accidental. The SS guards would often force prisoners – exhausted from hours of hard labour without sufficient food and water – to race up the stairs carrying blocks of stone. Those who survived the ordeal would often be placed in a line-up at the edge of a cliff known as "The Parachutists Wall" (German: Fallschirmspringerwand).[65] At gun-point each prisoner would have the option of being shot or pushing the prisoner in front of him off the cliff.[27] Other common methods of extermination of prisoners who were either sick, unfit for further labour or as a means of collective responsibility or after escape attempts included beating the prisoners to death by the SS guards and Kapos, starving to death in bunkers, hanging and mass shootings.[66][67] At times the guards or Kapos would either deliberately throw the prisoners on the 380 volt electric barbed wire fence,[67] or force them outside the boundaries of the camp and then shoot them on the pretence that they were attempting to escape.[68] Another method of extermination were icy showers – some 3,000 inmates died of hypothermia after having been forced to take an icy cold shower and then left outside in cold weather.[66] A large number of inmates were drowned in barrels of water at Gusen II.[69][70][note 7]

The Nazis also performed pseudo-scientific experiments on the prisoners. Among the most notorious doctors to organise them were Sigbert Ramsauer, Karl Gross, Eduard Krebsbach and Aribert Heim. Heim was dubbed "Doctor Death" by the inmates; he was in Gusen for seven weeks, which was enough to carry out his experiments.[71][72] Ramsauer also declared some 2,000 prisoners who applied to be transferred to a sanatorium mentally sick, and murdered them with injections of phenol in the course of the H-13 action.[66]

After the war one of the survivors, Dr. Antoni Gościński reported 62 ways of murdering people in the camps of Gusen I and Mauthausen.[66] Hans Maršálek estimated that an average life expectancy of newly arrived prisoners in Gusen varied from six months between 1940 and 1942, to less than three months in early 1945.[73] Paradoxically, with the growth of forced labour industry in various subcamps of Mauthausen, the situation of some of the prisoners improved significantly. While the food rations were increasingly limited every month, the heavy industry necessitated skilled specialists rather than unqualified workers and the brutality of the camp's SS and Kapos was limited. While the prisoners were still beaten on a daily basis and the Muselmänner were still exterminated, from early 1943 on some of the factory workers were allowed to receive food parcels from their families (mostly Poles and Frenchmen). This allowed many of them not only to evade the risk of starvation, but also to help other prisoners who had no relatives outside the camps – or who were not allowed to receive parcels.[74] Inmates were also beaten to death, like Viennese Jew Adolf Fruchthändler.

In February 1945, the camp was the site of Nazi war crime Mühlviertler Hasenjagd ("hare hunt") where around 500 escaped prisoners (mostly Soviet officers) were mercilessly hunted down and murdered by SS, local law enforcement and civilians.

Death toll

The Germans destroyed much of the camp's files and evidence and often gave newly arrived prisoners the camp numbers of those who had already been killed,[41] so the exact death toll of the Mauthausen-Gusen complex is impossible to calculate. The matter is further complicated due to some of the inmates of Gusen being murdered in Mauthausen, and at least 3,423 were sent to Hartheim Castle, 40.7 km (25.3 mi) away. Also, several thousands were killed in mobile gas chambers, without any mention of the exact number of victims in the remaining files.[75] Before their escape from the camps on 4 May 1945, the SS tried to destroy the evidence, allowing only approximately 40,000 victims to be identified. During the first days after the liberation, the camp's main chancellery was seized by the members of a Polish inmate resistance organization; they secured it against the wishes of other inmates who wanted to burn it.[76] After the war, the archives of the main chancellery was brought by one of the survivors to Poland, then passed to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Oświęcim.[77][78] Parts of the death register of Gusen I camp were secured by the Polish inmates, who took it to Australia after the war. In 1969 the files were given to the International Red Cross International Tracing Service.[75]

The surviving camp archives include personal files of 37,411 murdered prisoners, including 22,092 Poles, 5,024 Spaniards, 2,843 Soviet prisoners of war and 7,452 inmates of 24 other nationalities.[79] The surviving parts of the death register of KZ Gusen list an additional 30,536 names.[citation needed]

Apart from the surviving camp files of the subcamps of Mauthausen, the main documents used for an estimation of the death toll of the camp complexes are:

- A report by Józef Żmij, a survivor who had been working in the Gusen I camp's chancellery. His report is based on personally-made copies of yearly reports from the period between 1940 and 1944, and the camps' commander's daily reports for the period between 1 January 1945 and the day of the liberation.

- Original death register for the subcamp of Gusen held by the International Red Cross

- Personal notes of Stanisław Nogaj, another inmate who had been working in the chancellery of Gusen

- Death register prepared by the SS chief medic of the Mauthausen main chancellery for the subcamps of Gusen (similar records for the Mauthausen subcamp itself were destroyed)

As a result of these factors, the exact death toll of the entire Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp system varies considerably from source to source. Various scholars place it at between 122,766[note 8] and 320,000,[66] with other numbers also frequently quoted being 200,000[80] and "over 150,000".[81] Various historians place the total death toll in the four main camps of Mauthausen, Gusen I, Gusen II and Gusen III at between 55,000[41] and 60,000.[82][note 9] In addition, during the first month after the liberation additional 1,042 prisoners died in American field hospitals.[83]

| Death Toll Statistics Gusen I, II and III[note 10] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Józef Żmij |

Stanisław Nogaj |

KZ Gusen |

Hans Maršálek[16] |

Stanisław Dobosiewicz[84] |

| 1940 | 1,784 | 1,430 | 1,389 | 1,762 | |

| 1941 | 5,793 | 7,214 | 5,564 | 5,272 | 6,300 |

| 1942 | 6,088 | 7,203 | 5,005 | 7,410 | 9,534 |

| 1943 | 5,225 | 5,303 | 5,173 | 5,248 | 6,103 |

| 1944 | 5,921 | 4,790 | 4,691 | 4,091 | 5,488 |

| 1945 | 12,600 | 197 | 4,673 | 15,415 | |

| Undated | 2,843 | ||||

| Total | 37,411 | 24,707 | 30,536 | 33,451 | 44,602 |

Out of approximately 320,000 prisoners who were incarcerated in various subcamps of Mauthausen-Gusen throughout the war, only approximately 80,000 survived,[85] including between 20,487[83] and 21,386[86][note 11] in Gusen I, II and III.

-

Bodies being removed by German civilians for burial, after the liberation of Gusen concentration camp

-

Crematorium ovens at Mauthausen, modern view

-

Zyklon B, the gas used for the gas chambers

Staff

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2015) |

Several Norwegian Waffen SS volunteers worked as guards or as instructors for prisoners from Nordic countries, according to senior researcher Terje Emberland at the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities.[87]

Liberation and post-war heritage

During the final months before liberation, the camp's commander Franz Ziereis prepared for its defence against a possible Soviet offensive. Most of the inmates of German and Austrian nationality "volunteered" for the SS-Freiwillige Häftlingsdivision, an SS unit composed mostly of former concentration camp inmates and headed by Oskar Dirlewanger.[89] The remaining prisoners were rushed to build a line of granite anti-tank obstacles to the east of Mauthausen. The inmates unable to cope with the hard labour and malnutrition were exterminated in large numbers to free space for newly arrived evacuation transports from other camps, including most of the subcamps of Mauthausen-Gusen located in eastern Austria. In the final months of the war, the main source of dietary energy, that is the parcels of food sent through the International Red Cross, stopped and food rations became catastrophically low. The prisoners transferred to the "Hospital Subcamp" received one piece of bread per 20 inmates and roughly half a litre of weed soup a day.[90] This made some of the prisoners, previously engaged in various types of resistance activity, begin to prepare plans to defend the camp in case of an SS attempt to exterminate all the remaining inmates.[90]

It is not known why the prisoners of Gusen I and II were not exterminated en-masse, despite direct orders from Heinrich Himmler to murder them and prevent the use of their workforce by the Allies.[91] [90] Ziereis' plan assumed rushing all the prisoners into the tunnels of the underground factories of Kellerbau and blowing up the entrances.[92][93] The plan was known to one of the Polish resistance organizations which started an ambitious plan of gathering tools necessary to dig air vents in the entrances.[93]

On 28 April, under cover of a fictional air-raid alarm, some 22,000 prisoners of Gusen were rushed into the tunnels.[94] However, after several hours in the tunnels all of the prisoners were allowed to return to the camp.[94] Stanisław Dobosiewicz, the author of a monumental monograph of the Mauthausen-Gusen complex, explains that one of the possible causes of the failure of the German plan was that the Polish prisoners managed to cut the fuse wires. Ziereis himself stated in his testimony written on 25 May that it was his wife who convinced him not to follow the order from above.[95] Although the plan was abandoned, the prisoners feared that the SS might want to massacre the prisoners by other means, and the Polish, Soviet and French prisoners prepared a plan for an assault on the barracks of the SS guards in order to seize the arms necessary to put up a fight. A similar plan was also devised by the Spanish inmates.[95]

On 3 May the SS and other guards started to prepare for evacuation of the camp. The following day, the guards of Mauthausen were replaced with unarmed Volkssturm soldiers and an improvised unit formed of elderly police officers and fire fighters evacuated from Vienna. The police officer in charge of the unit accepted the "inmate self-government" as the camp's highest authority and Martin Gerken, until then the highest-ranking kapo prisoner in the Gusen's administration (in the rank of Lagerälteste, or the Camp's Elder), became the new de facto commander. He attempted to create an International Prisoner Committee that would become a provisional governing body of the camp until it was liberated by one of the approaching armies, but he was openly accused of co-operation with the SS and the plan failed. All work in the subcamps of Mauthausen stopped and the inmates focused on preparations for their liberation – or defence of the camps against a possible assault by the SS divisions concentrated in the area.[95] The remnants of several German divisions indeed assaulted the Mauthausen subcamp, but were repelled by the prisoners who took over the camp.[14] Of the main subcamps of Mauthausen-Gusen, only Gusen III was to be evacuated. On 1 May the inmates were rushed on a death march towards Sankt Georgen, but were ordered to return to the camp after several hours. The operation was repeated the following day, but called off soon afterwards. The following day, the SS guards deserted the camp, leaving the prisoners to their fate.[95]

On 5 May 1945 the camp at Mauthausen was approached by a squad of US Army Soldiers of the 41st Reconnaissance Squadron of the US 11th Armored Division, 3rd US Army. The reconnaissance squad was led by Staff Sergeant Albert J. Kosiek.[96] His troop disarmed the policemen and left the camp. By the time of its liberation, most of the SS-men of Mauthausen had already fled; around 30 who were remained were killed by the prisoners,[97] and a similar number were killed in Gusen II.[97] By 6 May all the remaining subcamps of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp complex, with the exception of the two camps in the Loibl Pass, were also liberated by American forces.[citation needed]

Among the inmates liberated from the camp was Lieutenant Jack Taylor, an officer of the Office of Strategic Services.[98][99] He had managed to survive with the help of several prisoners and was later a key witness at the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials carried out by the Dachau International Military Tribunal.[100] Another of the camp's survivors was Simon Wiesenthal, an engineer who spent the rest of his life hunting Nazi war criminals. Future Medal of Honor recipient Tibor "Ted" Rubin was imprisoned there as a young teenager; a Hungarian Jew, he vowed to join the US Army upon his liberation and later did just that, distinguishing himself in the Korean War as a corporal in the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.[101]

Following the capitulation of Germany, the Mauthausen-Gusen complex fell within the Soviet sector of occupation of Austria. Initially, the Soviet authorities used parts of the Mauthausen and Gusen I camps as barracks for the Red Army. At the same time, the underground factories were being dismantled and sent to the USSR as a war booty. After that, between 1946 and 1947, the camps were unguarded and many furnishings and facilities of the camp were dismantled, both by the Red Army and by the local population. In the early summer of 1947, the Soviet forces had blown the tunnels up and were then withdrawn from the area, while the camp was turned over to Austrian civilian authorities.[citation needed]

Memorials

Mauthausen was declared a national memorial site in 1949. Bruno Kreisky, the Chancellor of Austria, officially opened the Mauthausen Museum on 3 May 1975, 30 years after the camp's liberation.[2] A visitor centre was inaugurated in 2003, designed by the architects Herwig Mayer, Christoph Schwarz, and Karl Peyrer-Heimstätt, covering an area of 2,845 square metres (30,620 sq ft).[102]

The Mauthausen site remains largely intact, but much of what constituted the subcamps of Gusen I, II and III is now covered by residential areas built after the war.[103] A number of prominent Poles, Shevah Weiss and the Chief Rabbi of Poland Michael Schudrich have sent a letter of protest to Ministry of Internal Affairs of Austria. [104] [105]

Documentaries

- Mauthausen-Gusen: La memòria (2009) (in Valencian) by Rosa Brines. An 18-minute documentary about the republican Spaniards deported to Mauthausen and Gusen. It includes testimonies from survivors.

See also

- List of Nazi-German concentration camps

- Steyr-Münichholz subcamp

- Mühlviertler Hasenjagd

- Granitwerke Mauthausen

- Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark

- Eisenwerke Oberdonau

- Amicale de Mauthausen

- Mauthausen Trilogy

References

Footnotes

- ^ Oswald Pohl, apart from being a high-ranking SS member, owner of DEST and several other companies, and chief of administration and treasurer of various Nazi organizations, was also the managing director of the German Red Cross. In 1938, he transferred 8,000,000 Reichsmark from member fees to one of the accounts of the SS (SS-Spargemeinschaft e. V.), which in turn donated all the money to DEST in 1939.[5]

- ^ As stated in Reinhard Heydrich's memo of January 1, 1941.[15]

- ^ 11,000,000 Reichsmark was equivalent to roughly 4,403,000 US dollars or almost one million UK pounds by 1939 exchange rates;[29] In turn, 4,403,000 1939 dollars are roughly equivalent to 560,370,000 modern US dollars using the relative share of GDP as the main factor of comparison, or 96.4 million using the consumer price index.[30]

- ^ In reality the actual production never reached such levels.[36]

- ^ The subcamp inmate counts refer to the situation in late 1944 and early 1945, before the major reorganization of the camp's system and before the arrival of a large number of evacuation trains and death marches.

- ^ It is often mentioned that the mortality rate reached 58% in 1941, as compared with 36% at Dachau, and 19% at Buchenwald over the same period. Dobosiewicz – who made the most extensive study – compared various factors: his estimations were based on the number of prisoners to arrive in a year as compared to the number of that were murdered during a year.[5]

- ^ Stanisław Grzesiuk recalls that in 1941, and 1942, all Kapos in charge of every Block in Gusen had to drown two prisoners a day.[36]

- ^ As evidenced by one of the stone tablets commemorating the victims, erected after the war by Austrian authorities.

- ^ According to Martin Gilbert, there were 30,000 deaths in Mauthausen and its subcamps in the first four months of 1945. According to him, this was approximately half of the deaths in the whole history of the camp.[82]

- ^ Compiled from a larger table published in Stanisław Dobosiewicz's monograph;[84] the numbers are fragmentary and only include the numbers for Gusen I, II and III, without the numbers for other subcamps or the main camp in Mauthausen. Summary by Stanisław Dobosiewicz includes categories omitted by some of the sources, including roughly 2,744 former inmates who died immediately after liberation, both in the camp and in American field hospitals, as well as an approximate number of Jewish children (420) and prisoners in the Sick Camp (1900) who were not registered in the official camp statistics.

- ^ The difference in numbers given is most probably the result of the fact that Dobosiewicz included roughly 700 inmates who were held in the Revier at the time of liberation.[86]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 191–202.

- ^ a b c Bischof & Pelinka, pp. 185–190.

- ^ a b c d e f Haunschmied (2008), pp. 172–175.

- ^ Walden, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 449.

- ^ a b c Pike, p. 14.

- ^ Gębik, p. 332.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 5, 401.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 13.

- ^ a b c Haunschmied (2008), pp. 45–48.

- ^ Pike, p. 89.

- ^ Pike, p. 18.

- ^ Speer, pp. 367–368.

- ^ a b Żeromski, pp. 6–12.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 12.

- ^ a b c Maršálek (1995), p. 69.

- ^ Kunert, p. 30.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 13, 47.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 15.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 14.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 198.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 25, 196–197.

- ^ a b c Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 193.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 25.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 26.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 240.

- ^ a b Waller, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b "Memoriales históricos", ¶ Historia de los campos de concentración.

- ^ Derela, p. 1.

- ^ Williamson, p. 1.

- ^ M.S., ¶ Geschichte.

- ^ Pike, p. 98.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1980), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Haunschmied (1997), p. 1325.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 194.

- ^ a b c d e f Grzesiuk, p. 392.

- ^ a b "Nazi secret weapons site claims refuted". The Local. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Terrance, p. 142.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 343.

- ^ a b c d Abzug, pp. 106–110.

- ^ Shermer & Grobman, pp. 168–175.

- ^ Nogaj, p. 64.

- ^ Piotrowski, p. 25.

- ^ Kunert, p. 104.

- ^ Wnuk (1972), pp. 100–105.

- ^ STA & mm, "Že pred današnjo…".

- ^ Filipkowski, p. 1.

- ^ Kirchmayer, p. 576.

- ^ a b c Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 365–367.

- ^ Freund & Greifeneder, "Die Zelte waren für höchstens 800 Personen…".

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 204.

- ^ Nizkor, KZ Gusen Memorial Committee, "KZ Gusen I Concentration Camp at Langenstein", "KZ Gusen Brothel".

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 205.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 108.

- ^ Brown, p. 288.

- ^ a b Friedlander, pp. 33–69.

- ^ Myczkowski, p. 31.

- ^ Simon Wiesenthal Center, "Mauthausen".

- ^ Bloxham, p. 210.

- ^ a b Burleigh, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Pike, p. 97.

- ^ a b Krukowski, pp. 292–297.

- ^ Weissman, pp. 2–3.

- ^ KZ-Gedenkstaette Mauthausen, "Parachute Jump".

- ^ a b c d e Wnuk (1961), pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b Maida, "The systematic and deliberate extermination by hunger…".

- ^ Schmidt, pp. 146–148.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 12.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 102, 276.

- ^ Fuchs, p. 1.

- ^ Schmidt & Loehrer, p. 146.

- ^ Maršálek (1968), p. 32; as cited in: Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 192–193.

- ^ Grzesiuk, pp. 252–255.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 418–426.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1980), p. 486.

- ^ sm, "Dokumentacja z Mauthausen trafiła do muzeum…".

- ^ Cyra, "For unknown reasons, the documents…".

- ^ Wlazłowski, pp. 7–12.

- ^ Pike, p. XII.

- ^ Filip, Łomacki et al., p. 56.

- ^ a b Gilbert, p. 976.

- ^ a b Wlazłowski, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 421.

- ^ Hlaváček, "4. května Mezinárodní výbor…".

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 397.

- ^ "Verdens Gang", p. 1.

- ^ Pike, p. 256.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 323.

- ^ a b c Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 374–375.

- ^ Haunschmied (2008), pp. 219–220.

- ^ Haunschmied (2008), pp. 220.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1980), pp. 446, 451–452.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1980), p. 450–452.

- ^ a b c d Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 382–388.

- ^ Pike, pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 395–397.

- ^ UDT-SEAL Association, "Lt. Jack Taylor of the OSS…".

- ^ Pike, p. 237.

- ^ Taylor, ¶ "The below narrative is the full and complete…".

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients – Korean War: TIBOR RUBIN". United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ van Uffelen, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Terrance, pp. 138–139.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Protest against Devastation of the Concentration Camp Site

Bibliography

- KZ Gusen Memorial Committee (corporate author) (1997). "KZ Gusen I Concentration Camp at Langenstein". The Nizkor Project. Nizkor. Retrieved 2006-04-10.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Robert Abzug (1987). Inside the Vicious Heart. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 106–110. ISBN 0-19-504236-0.

- Günter Bischof; Anton Pelinka (1996). Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transaction Publishers. pp. 185–190. ISBN 1-56000-902-0.

- Donald Bloxham (2003). Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-19-925904-6.

- Daniel Patrick Brown (2002). The Camp Women: The Female Auxiliaries Who Assisted the SS in Running the Nazi Concentration Camp System. Schiffer Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 0-7643-1444-0.

- Michael Burleigh (1997). Ethics and Extermination: Reflections on Nazi Genocide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 0-521-58816-2.

- Adam Cyra (2004). "Mauthausen Concentration Camp Records in the Auschwitz Museum Archives". Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Historical Research Section, Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. Archived from the original on September 30, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Michał Derela (2005). "The prices of Polish armament before 1939". The PIBWL military site. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- Template:Pl icon Stanisław Dobosiewicz (1977). Mauthausen/Gusen; obóz zagłady. Warsaw: Ministry of National Defence Press. p. 449. ISBN 83-11-06368-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Stanisław Dobosiewicz (1980). Mauthausen/Gusen; Samoobrona i konspiracja. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa MON. p. 486. ISBN 83-11-06497-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Stanisław Dobosiewicz (2000). Mauthausen-Gusen; w obronie życia i ludzkiej godności. Warsaw: Bellona. pp. 191–202. ISBN 83-11-09048-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon various authors (1962). Marian Filip; Mikołaj Łomacki (eds.). Wrogom ku przestrodze: Mauthausen 5 maja 1945. Warsaw: ZG ZBoWiD. p. 135.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Piotr Filipkowski (2005). "Auschwitz w drodze do Mauthausen". Europe According to Auschwitz. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:De icon Florian Freund; Harald Greifeneder (2005). "Zeltlager". mauthausen-memorial.at. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - various authors; Henry Friedlander (1981). "The Nazi Concentration Camps". In Michael D. Ryan (ed.). Human Responses to the Holocaust Perpetrators and Victims, Bystanders and Resisters. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 33–69. ISBN 0-88946-901-6.

- Dale Fuchs (October 2005). "Nazi war criminal escapes Costa Brava police search". Guardian (October 17, 2005). Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- Template:Pl icon Władysław Gębik (1972). Z diabłami na ty. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Morskie. p. 332.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Martin Gilbert (1987). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Owl Books. p. 976. ISBN 0-8050-0348-7.

- Template:Pl icon Stanisław Grzesiuk (1985). Pięć lat kacetu. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 392. ISBN 83-05-11108-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Rudolf Haunschmied; Harald Faeth (1997). "B8 "BERGKRISTALL" (KL Gusen II)". Tunnel and Shelter Researching. Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

- Rudolf A. Haunschmied; Jan-Ruth Mills; Siegi Witzany-Durda (2008). St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen – Concentration Camp Mauthausen Reconsidered. Norderstedt: Books on Demand. p. 289. ISBN 978-3-8334-7610-5. OCLC 300552112.

- Template:Cs icon Stanislav Hlaváček (2000). "Historie KTM". Koncentrační Tábor Mauthausen; Pamětní tisk k 55. výročí osvobození KTM. Retrieved 2006-05-18.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Jerzy Kirchmayer (1978). Powstanie warszawskie. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 576. ISBN 83-05-11080-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Stefan Krukowski (1966). "Pamięci lekarzy". Nad pięknym modrym Dunajem; Mauthausen 1940–1945. Tadeusz Żeromski (foreword). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 292–297. PB 9330/66.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Various authors (2009). Andrzej Kunert (ed.). Człowiek człowiekowi… Niszczenie polskiej inteligencji w latach 1939–1945 KL Mauthausen/Gusen. Warsaw: Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa. p. 104.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - KZ-Gedenkstaette Mauthausen (corporate author). "Parachute Jump". Mauthausen Memorial. KZ-Gedenkstaette Mauthausen. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Bruno Maida. "The gas chamber of Mauthausen – History and testimonies of the Italian deportees; A Brief history of the camp". National Association of Italian political deportees in the Nazi concentration camps. Fondazione Memoria della Deportazione.

- Hans Maršálek (1968). Konzentrazionslager Gusen. Vienna. p. 32.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Template:De icon Hans Maršálek (1995). Die Geschichte des Konzentrationslagers Mauthausen. Wien-Linz: Österreichischen Lagergemeinschaft Mauthausen u. Mauthausen-Aktiv Oberösterreich.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Adam Myczkowski (1946). Poprzez Dachau do Mauthausen-Gusen. Kraków: Księgarnia Stefana Kamińskiego. p. 31.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:De icon M.S. (2000). "Linz – Eisenwerke Oberdonau". Österreichs Geschichte im Dritten Reich. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

- Template:Pl icon Stanisław Nogaj (1945). Gusen; Pamiętnik dziennikarza. Katowice-Chorzów: Komitet byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Gusen. p. 64.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - David Wingeate Pike (2000). Spaniards in the Holocaust: Mauthausen, Horror on the Danube. London: Routledge. p. 480. ISBN 0-415-22780-1.

- Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998). Poland's holocaust: ethnic strife, collaboration with occupying forces and genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help) - Elizabeth C. Richardson (1995). "United States vs. Leprich". Administrative Law and Procedure. Thomson Delmar Learning. pp. 162–164. ISBN 0-8273-7468-2.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - various authors (2008). Amy Schmidt; Gudrun Loehrer (eds.). "The Mauthausen Concentration Camp Complex: World War II and Postwar Records" (PDF). Reference Information Paper. 115. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration: 145–148. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- James Schmidt (2005). ""Not These Sounds": Beethoven at Mauthausen" (PDF). Philosophy and Literature. 29. Boston: Boston University: 146–163. doi:10.1353/phl.2005.0013. ISSN 0190-0013. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- Michael Shermer; Alex Grobman (2002). "The Gas Chamber at Mauthausen". Denying History: Who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and Why Do They Say It?. University of California Press. pp. 168–175. ISBN 0-520-23469-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon sm (2006-04-03). "Pracownicy muzeum Auschwitz zeskanowali już kartotekę Mauthausen". 61. rocznica wyzwolenia Auschwitz. Polish Press Agency. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Albert Speer (1970). Inside The Third Reich. New York: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 0-88365-924-7.

- Template:Sl icon STA, mm (May 2012). "Taborišče, v katerem je umrlo 1500 Slovencev". Mladina (13. 5. 2012). ISSN 1580-5352. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Jack Taylor (2003). "OSS Archives: The Dupont Mission". The BLAST; UDT-SEAL Association. Archived from the original on 2006-01-27. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- Marc Terrance (1999). Concentration Camps: A Traveler's Guide to World War II Sites. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-839-8.

- UDT-SEAL Association (corporate author) (2006). "Jack Taylor, American Agent Who Survived Mauthausen". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Chris van Uffelen (2010). Contemporary Museums – Architecture, History, Collections. Braun Publishing. pp. 150–153. ISBN 9783037680674.

- Geoffrey R. Walden (2000-07-20). "Gusen Concentration Camp / Project B-8 "Bergkristall" Tunnel System". The Third Reich in Ruins. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- James Waller (2002). Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass Killing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 0-19-514868-1.

- Gary Weissman (2004). Fantasies of Witnessing: Postwar Efforts to Experience the Holocaust. Cornell University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-8014-4253-2.

- Simon Wiesenthal Center (corporate author). "Selected Holocaust Glossary: Terms, Places and Personalities". Florida Holocaust Museum webpage. Florida Holocaust Museum. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Samuel H. Williamson (March 2011). "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present". MeasuringWorth.

- Template:Pl icon Zbigniew Wlazłowski (1974). Przez kamieniołomy i kolczasty drut. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 184. PB 1974/7600.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon various authors; Włodzimierz Wnuk (1961). "Śmiertelne kąpiele". Oskarżamy! Materiały do historii obozu koncentracyjnego Mauthausen-Gusen. Katowice: Klub Mauthausen-Gusen ZBoWiD. pp. 20–22.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Włodzimierz Wnuk (1972). "Z Hiszpanami w jednym szeregu". Byłem z wami. Warsaw: PAX. pp. 100–105.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Tadeusz Żeromski (1983). Kazimierz Rusinek (ed.). Międzynarodówka straceńców. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 76+19. ISBN 83-05-11175-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:Es icon various authors (2005). "Historia de los campos de concentración: El sistema de campos de concentración nacionalsocialista, 1933–1945: un modelo europeo". Memoriales históricos, 1933–1945.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Template:No icon Verdens Gang (corporate author) (2010-11-15). "Norske vakter jobbet i Hitlers konsentrasjonsleire". Verdens Gang (15–11–2010). ISSN 0805-5203. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Evelyn Le Chêne (1971). Mauthausen, The History of a Death Camp. London: Methuen. p. 296. ISBN 0-416-07780-3.

- Snyder, Timothy D. (2015). Black Earth. The Holocaust As History and Warning. ISBN 978-1-101-90346-9.

- Austrian Ministry of the Interior (corporate author) (2005). Das sichtbare Unfassbare / The Visible Part – Fotografien aus dem Konzentrationslager Mauthausen/ Photographs of Mauthausen Concentration Camp. Vienna: Mandelbaum Verlag. p. 220. ISBN 978385476-158-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)

External links

- USHMM United States Holocaust Memorial Museum contains more than 500 pictures of Mauthausen-Gusen

- Interviews with American servicemen imprisoned at Mauthausen

- Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

- Nazi concentration camps in Austria

- Amstetten, Lower Austria

- Amstetten District

- The Holocaust in Austria

- 1938 establishments in Germany

- 1945 disestablishments

- Buildings and structures in Upper Austria

- Museums in Upper Austria

- World War II museums

- History museums in Austria

- Military and war museums in Austria

- Monuments and memorials in Austria