Natural capital

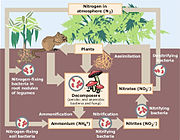

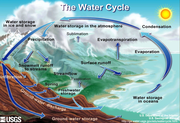

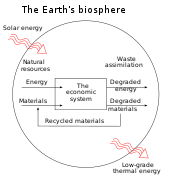

Natural capital is the world's stock of natural resources, which includes geology, soils, air, water and all living organisms. Some natural capital assets provide people with free goods and services, often called ecosystem services. Two of these (clean water and fertile soil) underpin our economy and society, and thus make human life possible.[3][4]

It is an extension of the economic notion of capital (resources which enable the production of more resources) to goods and services provided by the natural environment. For example, a well-maintained forest or river may provide an indefinitely sustainable flow of new trees or fish, whereas over-use of those resources may lead to a permanent decline in timber availability or fish stocks. Natural capital also provides people with essential services, like water catchment, erosion control and crop pollination by insects, which in turn ensure the long-term viability of other natural resources. Since the continuous supply of services from the available natural capital assets is dependent upon a healthy, functioning environment, the structure and diversity of habitats and ecosystems are important components of natural capital.[5] Methods, called 'natural capital asset checks', help decision-makers understand how changes in the current and future performance of natural capital assets will impact human well-being and the economy.[6]

History of the concept

| Part of a series on |

| Ecological economics |

|---|

|

The term 'natural capital' was first used in 1973 by E.F. Schumacher in his book Small Is Beautiful[7] and was developed further by Herman Daly, Robert Costanza, and other founders of the science of Ecological Economics, as part of a comprehensive critique of the shortcomings of conventional economics.[8][9] Natural capital is a concept central to economic assessment ecosystem services valuation which revolves around the idea, that non-human life produces goods and services that are essential to life. Thus, natural capital is essential to the sustainability of the economy.

In a traditional economic analysis of the factors of production, natural capital would usually be classified as "land" distinct from traditional "capital." The historical distinction between "land" and "capital" defined “land” as naturally occurring with a fixed supply, whereas “capital,” as originally defined referred only to man-made goods. (e.g., Georgism[10][11]) It is, however, misleading to view "land" as if its productive capacity is fixed, because natural capital can be improved or degraded by the actions of man over time (see Environmental degradation). Moreover, natural capital yields benefits and goods, such as timber or food, which can be harvested by humans. These benefits are similar to those realized by owners of infrastructural capital which yields more goods, such as a factory which produces automobiles just as an apple tree produces apples.

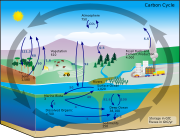

Ecologists are teaming up with economists to measure and express values of the wealth of ecosystems as a way of finding solutions to the biodiversity crisis.[12][13][14] Some researchers have attempted to place a dollar figure on ecosystem services such as the value that the Canadian boreal forest's contribution to global ecosystem services. If ecologically intact, the boreal forest has an estimated value of US$3.7 trillion. The boreal forest ecosystem is one of the planet's great atmospheric regulators and it stores more carbon than any other biome on the planet.[15] The annual value for ecological services of the Boreal Forest is estimated at US$93.2 billion, or 2.5 greater than the annual value of resource extraction.

The economic value of 17 ecosystem services for the entire biosphere (calculated in 1997) has an estimated average value of US$33 trillion per year.[16] These ecological economic values are not currently included in calculations of national income accounts, the GDP and they have no price attributes because they exist mostly outside of the global markets.[17][18] The loss of natural capital continues to accelerate and goes undetected or ignored by mainstream monetary analysis.[19]

Within the international community the basic principle is not controversial, although much uncertainty exists over how best to value different aspects of ecological health, natural capital and ecosystem services. Full-cost accounting, triple bottom line, measuring well-being and other proposals for accounting reform often include suggestions to measure an "ecological deficit" or "natural deficit" alongside a social and financial deficit. It is difficult to measure such a deficit without some agreement on methods of valuation and auditing of at least the global forms of natural capital (e.g. value of air, water, soil).[20]

All uses of the term currently differentiate natural from man-made or infrastructural capital in some way. Indicators adopted by United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure natural biodiversity use the term in a slightly more specific way. According to the OECD, natural capital is “natural assets in their role of providing natural resource inputs and environmental services for economic production” and is “generally considered to comprise three principal categories: natural resources stocks, land, and ecosystems.”

The concept of "natural capital" has also been used by the Biosphere 2 project, and the Natural Capitalism economic model of Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, and Hunter Lovins. Recently, it has begun to be used by politicians, notably Ralph Nader, Paul Martin Jr., and agencies of the UK government, including its Natural Capital Committee and the London Health Observatory.

In Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution[21] the author claims that the "next industrial revolution" depends on the espousal of four central strategies: "the conservation of resources through more effective manufacturing processes, the reuse of materials as found in natural systems, a change in values from quantity to quality, and investing in natural capital, or restoring and sustaining natural resources."[22]

Natural capital declaration

In June 2012 a 'natural capital declaration' (NCD) was launched at the Rio+20 summit held in Brazil. An initiative of the global finance sector, it was signed by 40 CEOs to 'integrate natural capital considerations into loans, equity, fixed income and insurance products, as well as in accounting, disclosure and reporting frameworks.' They worked with supporting organisations to develop tools and metrics to integrate natural capital factors into existing business structures.[23]

In summary, its four key aims are to:

- Increase understanding of business dependency on natural capital assets;

- Support development of tools to integrate natural capital considerations into the decision-making process of all financial products and services;

- Help build a global consensus on integrating natural capital into private sector accounting and decision-making;

- Encourage a consensus on integrated reporting to include natural capital as one of the key components of an organisation's success.

Natural Capital Protocol

In July 2016, the Natural Capital Coalition[24] released the Natural Capital Protocol.[25] The Protocol provides a standardised framework for organisations to identify, measure and value their direct and indirect impacts and dependencies on natural capital. The Protocol harmonises existing tools and methodologies, and guides organisations towards the information they need to make strategic and operational decisions that include impacts and dependencies on natural capital.

The Protocol was developed in a unique collaboration between 38 organisations who signed voluntary, pre-competitive contracts.[26]

The Protocol is available on a creative commons license and is free for organisations to apply.

Internationally agreed standard

Environmental-economic accounts provide the conceptual framework for integrated statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy, including the impacts of the economy on the environment and the contribution of the environment to the economy. A coherent set of indicators and descriptive statistics can be derived from the accounts that inform a wide range of policies.

These include, but are not limited to:

The System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) contains the internationally agreed standard concepts, definitions, classifications, accounting rules and tables for producing internationally comparable statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy. The SEEA is a flexible system in the sense that its implementation can be adapted to countries' specific situations and priorities. Coordination of the implementation of the SEEA and on-going work on new methodological developments is managed and supervised by the UN Committee of Experts on Environmental-Economic Accounting (UNCEEA). The final, official version of the SEEA Central Framework was published in February 2014.

Private sector approaches

Some studies envisage a private sector natural capital 'ecosystem', including investors, assets and regulators.[27]

Criticism

Whilst measuring the components of natural capital in any region is a relatively straightforward process, both the task and the rationale of putting a monetary valuation on them, or on the value of the goods and services they freely give us, has proved more contentious.[28] Within the UK, Guardian columnist, George Monbiot, has been critical of the work of the government's Natural Capital Committee and of other attempts to place any sort of monetary value on natural capital assets, or on the free ecosystem services they provide us with. In a speech referring to a report to government which suggested that better protection of the UK's freshwater ecosystems would yield an enhancement in aesthetic value of £700m, he derided attempts 'to compare things which cannot be directly compared'.[29] He went on to say:

These figures, ladies and gentlemen, are marmalade. They are finely shredded, boiled to a pulp, heavily sweetened ... and still indigestible. In other words they are total gibberish.

— G. Monbiot

Others have defended efforts to integrate the valuation of natural capital into local and national economic decision-making, arguing that it puts the environment on a more balanced footing when weighed against other commercial pressures, and that 'valuation' of those assets is not the same as monetisation.[30][31]

See also

- Bioeconomics (biophysical)

- Biocapacity

- Conservation biology

- Earth Economics (organization)

- Ecodynamics

- Ecological deficit

- Ecological economics

- Ecological footprint

- Ecology

- Econophysics

- Ecosystem services

- Energy accounting

- Environmental degradation

- Environmental economics

- Environmental protection

- Habitat conservation

- Natural capital accounting

- Natural Capital Committee

- Natural Capital Initiative

- Oil depletion

- Payment for ecosystem services

- Population dynamics

- Renewable resource

- Sustainability

- Sustainable development

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity

- Thermoeconomics

References

Notes

- ^ Valiela, Ivan; Bowen, Jennifer L.; York, Joanna K. (2001). "Mangrove Forests: One of the World's Threatened Major Tropical Environments". BioScience. 51 (10): 807–815. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0807:mfootw]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1525-3244. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Why are Rainforests Important?". www.rainforestconcern.org. Archived from the original on 2016-01-20. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "What is natural capital?". naturalcapitalforum.com. World Forum on Natural Capital. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "What is Natural Capital". www.naturalcapitalcoalition.org. Natural Capital Coalition. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Search - The Encyclopedia of Earth". www.eoearth.org.

- ^ "UK NEAFO Work Package 1: Natural capital asset check – Annex 4: Case studies". uknea.unep-wcmc.org. UK National Ecosystem Assessment. p. 3. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Schumacher, E.F (1973). Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered.

- ^ COSTANZA, ROBERT; DALY, HERMAN E. (March 1992). "Natural Capital and Sustainable Development". Conservation Biology. 6 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.610037.x. ISSN 0888-8892.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (June 1999). "An Introduction to Ecological Economics. Edited by Robert Costanza, John Cumberland, Herman Daly, Robert Goodland and Richard Norgaard, St. Lucie Press. 1997, pp. 288". Ecological Economics. 29 (3): 488–490. doi:10.1016/s0921-8009(99)00029-4. ISBN 1884015727. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ [1] - Progress and Poverty by Henry George, Chapter 2.

- ^ "Economic Definitions". www.henrygeorge.org.

- ^ Edwards, P. J.; Abivardi, C. (1998). "The value of biodiversity: Where ecology and economy blend". Biological Conservation. 83 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(97)00141-9.

- ^ Naidoo, R.; Malcolm, T.; Tomasek, A. (2009). "Economic benefits of standing forests in highland areas of Borneo: quantification and policy impacts" (PDF). Conservation Letters. 2: 35–44. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263x.2008.00041.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-04. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ Zhoua, X.; Al-Kaisib, M.; Helmers, M. J. (2009). "Cost effectiveness of conservation practices in controlling water erosion in Iowa". Soil and Tillage Research. 106 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1016/j.still.2009.09.015.

- ^ Jonsson, M.; Wardle, D. A. (2009). "Structural equation modelling reveals plant-community drivers of carbon storage in boreal forest ecosystems". Biology Letters. 6 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0613. PMC 2817262. PMID 19755530.

- ^ Costanza, R.; et al. (1997). "The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital" (PDF). Nature. 387 (6630): 253–260. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..253C. doi:10.1038/387253a0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-26.

- ^ Ferguson, K. (2006). "The True Value of Forests". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 4 (9): 456. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[452:D]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3868812.

- ^ Anielski, M.; Wilson, S. (2005). "Counting Canada's Natural Capital: Assessing the Real value of Canada's Boreal Ecosystems" (PDF). Can. Bor. Ini., Pembina Institute, Ottawa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-07.

- ^ Wakernagel, M.; Rees, W. E. (1997). "Perceptual and structural barriers to investing in natural capital: Economics from an ecological footprint perspective". Ecological Economics. 20 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00077-8.

- ^ "Sustainability Pathways: Full-cost accounting". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- ^ Hawken, Paul; Amory Lovins; Hunter Lovins (1999). Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution.

- ^ Book Review: Natural Capitalism Archived 2010-01-03 at the Wayback Machine from Socialfunds.com[permanent dead link]. Retrieved April 2009.

- ^ "Natural Capital Declaration". www.naturalcapitaldeclaration.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Log In ‹ Natural Capital Coalition — WordPress". naturalcapitalcoalition.org.

- ^ "Natural Capital Coalition - Protocol". naturalcapitalcoalition.org.

- ^ "Natural Capital Coalition - Protocol Development". naturalcapitalcoalition.org.

- ^ https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/fr/Documents/sustainability-services/deloitte_etude-emergence-natural-capital-2018.pdf

- ^ Conniff, Richard (18 October 2012). "What's Wrong with Putting a Price on Nature?". e360.yale.edu. Yale University. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Monbiot, George (24 July 2014). "Put a price on nature? We must stop this neoliberal road to ruin". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Paddison, Laura (1 August 2014). "Is natural capital a 'neoliberal road to ruin'?- experts discuss". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Natural Capital (Does putting a value on natural capital mean it will be 'sold off'?)". www.naturalcapitalcommittee.org. Natural Capital Committee. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

Further reading

- Pearce, D. 1993. Blueprint 3: Measuring Sustainable Development. Earthscan. ISBN 1-85383-183-2

- Jansson, AnnMari; et al. (1994). Investing in Natural Capital : The Ecological Economics Approach to Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 504 pp. ISBN 1-55963-316-6.

- Daily, Gretchen C. (editor) (1997). Nature's Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 392 pp. ISBN 1-55963-476-6.

- Prugh, Thomas; Robert Costanza et al. (1999). Natural capital and human economic survival. Solomons, Md.: International Society for Ecological Economics, 180 pp. ISBN 1-56670-398-0.

- Helm, Dieter (2015). Natural Capital - Valuing Our Planet. Yale University Press; 277 pp. ISBN 978-0-300-21098-9

External links

- Costanza, Robert (Lead Author); Cutler J. Cleveland (Topic Editor). 2008. "Natural capital." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). First published in the Encyclopedia of Earth February 26, 2007; Last revised July 31, 2008; Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- Earth Economics Natural Capital Accounting Solutions Article [2]

- Natural Capital Project. A joint venture among The Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University, The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund.

- NOAA Economics US Economic Benefits of Natural Systems to Business and Society.

- Ecosystem Valuation Toolkit [3]

- Lacombe Morgane and Aronson James, 2009. Restoring Natural Capital in Arid and Semiarid Regions Combining Ecosystem Health with Human Wellbeing. Les dossiers thématiques du CSFD. N° 7.

- Earth Economics [4]

- http://unstats.un.org/unsd/envaccounting/seea.asp System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA)

- http://www.naturalcapitalcoalition.com[permanent dead link]

- http://naturalcapitalforum.com in 2015

- http://teebweb.org The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20150426071137/http://unstats.un.org/unsd/envaccounting/White_cover.pdf SEEA Central Framework

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160909034301/http://envisionation.co.uk/index.php/blogs/nick-breeze-blogs/151-partha-dasgupta-natural-capital Nick Breeze Interview with Economist Sir Partha Dasgupta, "What is Natural Capital?"