Ordination of women

The ordination of women to ministerial or priestly office is an increasingly common practice among some contemporary major religious groups.[2] It remains a controversial issue in certain religious groups in which ordination[a] was traditionally reserved for men.[2][3][4][b]

In some cases, women have been permitted to be ordained, but not to hold higher positions, such as (until July 2014) that of bishop in the Church of England.[9] Where laws prohibit sex discrimination in employment, exceptions are often made for clergy (for example, in the United States) on grounds of separation of church and state.

Ancient pagan religions

[edit]Sumer and Akkad

[edit]

- Sumerian and Akkadian EN were top-ranking priestesses distinguished by special ceremonial attire and holding equal status to high priests. They owned property, transacted business, and initiated the hieros gamos ceremony with priests and kings.[10] Enheduanna (2285–2250 BC), an Akkadian princess, was the first known holder of the title "EN Priestess".[11]

- Ishtaritu were temple prostitutes who specialized in the arts of dancing, music, and singing and served in the temples of Ishtar.[12]

- Puabi was a NIN, an Akkadian priestess of Ur in the 26th century BC.

- Nadītu, sometimes described as priestesses in modern literature, are attested from various cities from the Old Babylonian period. They were recruited from various social groups, ranging from craftsmen to royal families, and were supposed to remain childless; they owned property and transacted business.

- In Sumerian epic texts such as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, Nu-Gig were priestesses in temples dedicated to Inanna, or may be a reference to the goddess herself.[13]

- Qadishtu, Hebrew Qedesha (קדשה) or Kedeshah,[14] derived from the root Q-D-Š,[15][16] are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as sacred prostitutes usually associated with the goddess Asherah.

Ancient Egypt

[edit]

In Ancient Egyptian religion, God's Wife of Amun was the highest ranking priestess; this title was held by a daughter of the High Priest of Amun, during the reign of Hatshepsut, while the capital of Egypt was in Thebes during the second millennium BC (circa 2160 BC).

Later, Divine Adoratrice of Amun was a title created for the chief priestess of Amun. During the first millennium BC, when the holder of this office exercised her largest measure of influence, her position was an important appointment facilitating the transfer of power from one pharaoh to the next, when his daughter was adopted to fill it by the incumbent office holder. The Divine Adoratrice ruled over the extensive temple duties and domains, controlling a significant part of the ancient Egyptian economy.

Ancient Egyptian priestesses:

- Gautseshen

- Henutmehyt

- Henuttawy

- Hui

- Iset

- Karomama Meritmut

- Maatkare Mutemhat

- Meritamen

- Neferhetepes is the earliest attested priestess of Hathor.[17]

- Neferure

- Tabekenamun a priestess of Hathor as well as a priestess of Neith.

Ancient Greece

[edit]

In ancient Greek religion, some important observances, such as the Thesmophoria, were made by women. Priestesses, Hiereiai, served in many different cults of many divinities, with their duties varying depending on the cult and the divinity in which they served.

Priestesses played a major role in the Eleusinian Mysteries, in which they served on many levels, from the High Priestess of Demeter and Dadouchousa Prietess to the Panageis and Hierophantides. The Gerarai were priestesses of Dionysus who presided over festivals and rituals associated with the god.

A body of priestesses might also maintain the cult at a particular holy site, such as the Peleiades at the oracle of Dodona. The Arrephoroi were young girls ages seven to twelve who worked as servants of Athena Polias on the Athenian Acropolis and were charged with conducting unique rituals under the surveillance of the High Priestess of Athena Polias. The Priestess of Hera at Argos served at the Heraion of Argos and enjoyed great prestige in all Greece.

At several sites women priestesses served as oracles, the most famous of which is the Oracle of Delphi. The priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi was the Pythia, credited throughout the Greco-Roman world for her prophecies, which gave her a prominence unusual for a woman in male-dominated ancient Greece. The Phrygian Sibyl presided over an oracle of Apollo in Anatolian Phrygia. The inspired speech of divining women, however, was interpreted by male priests; a woman might be a mantic (mantis) who became the mouthpiece of a deity through possession, but the "prophecy of interpretation" required specialized knowledge and was considered a rational process suited only to a male '"prophet" (prophētēs).[18][19]

Ancient Rome

[edit]

The Latin word sacerdos, "priest", is the same for both the grammatical genders. In Roman state religion, the Vestal Virgins were responsible for the continuance and security of Rome as embodied by the sacred fire that they were required to tend on pain of extreme punishment. The Vestals were a college of six sacerdotes (plural) devoted to Vesta, goddess of the hearth, both the focus of a private home (domus) and the state hearth that was the center of communal religion. Freed of the usual social obligations to marry and rear children, the Vestals took a vow of chastity in order to devote themselves to the study and correct observance of state rituals that were off-limits to the male colleges of priests.[20] They retained their religious authority until the Christian emperor Gratian confiscated their revenues and his successor Theodosius I closed the Temple of Vesta permanently.[21][22]

The Romans also had at least two priesthoods that were each held jointly by a married couple, the rex and regina sacrorum, and the flamen and flaminica Dialis. The regina sacrorum ("queen of the sacred rites") and the flaminica Dialis (high priestess of Jupiter) each had her own distinct duties and presided over public sacrifices, the regina on the first day of every month, and the flaminica every nundinal cycle (the Roman equivalent of a week). The highly public nature of these sacrifices, like the role of the Vestals, indicates that women's religious activities in ancient Rome were not restricted to the private or domestic sphere.[23] So essential was the gender complement to these priesthoods that if the wife died, the husband had to give up his office. This is true of the flaminate, and probably true of the rex and regina.[23]

The title sacerdos was often specified in relation to a deity or temple,[23][24] such as a sacerdos Cereris or Cerealis, "priestess of Ceres", an office never held by men.[25] Female sacerdotes played a leading role in the sanctuaries of Ceres and Proserpina in Rome and throughout Italy that observed so-called "Greek rite" (ritus graecus). This form of worship had spread from Sicily under Greek influence, and the Aventine cult of Ceres in Rome was headed by male priests.[26] Only women celebrated the rites of the Bona Dea ("Good Goddess"), for whom sacerdotes are recorded.[27]: 371, 377 [c] The Temple of Ceres in Rome was surved by the Priestess of Ceres, Sacerdos Cereris, and the Temple of Bona Dea by the Priestess of Bona Dea, Sacerdos Bonae Deae. Other Priestesses were the Sacerdos Liberi, Sacerdos Fortunae Muliebris and the Sacerdos Matris Deum Magnae Idaeae; sacerdos also served as priestesses of the Imperial cult.

From the Mid Republic onward, religious diversity became increasingly characteristic of the city of Rome. Many religions that were not part of Rome's earliest state religion offered leadership roles as priests for women, among them the imported cult of Isis and of the Magna Mater ("Great Mother", or Cybele). An epitaph preserves the title sacerdos maxima for a woman who held the highest priesthood of the Magna Mater's temple near the current site of St. Peter's Basilica.[29] Inscriptions for the Imperial era record priestesses of Juno Populona and of deified women of the Imperial household.[23]

Under some circumstances, when cults such as mystery religions were introduced to Romans, it was preferred that they be maintained by women. Although it was Roman practice to incorporate other religions instead of trying to eradicate them,[30]: 4 the secrecy of some mystery cults was regarded with suspicion. In 189 BCE, the senate attempted to suppress the Bacchanals, claiming the secret rites corrupted morality and were a hotbed of political conspiracy. One provision of the senatorial decree was that only women should serve as priests of the Dionysian religion, perhaps to guard against the politicizing of the cult,[31] since even Roman women who were citizens lacked the right to vote or hold political office. Priestesses of Liber, the Roman god identified with Dionysus, are mentioned by the 1st-century BC scholar Varro, as well as indicated by epigraphic evidence.[23]

Other religious titles for Roman women include magistra, a high priestess, female expert or teacher; and ministra, a female assistant, particularly one in service to a deity. A magistra or ministra would have been responsible for the regular maintenance of a cult. Epitaphs provide the main evidence for these priesthoods, and the woman is often not identified in terms of her marital status.[23][24]

Buddhism

[edit]

The tradition of the ordained monastic community in Buddhism (the sangha) began with the Buddha, who established an order of monks.[34] According to the scriptures,[35] later, after an initial reluctance, he also established an order of nuns. Fully ordained Buddhist nuns are called bhikkhunis.[36][37] Mahapajapati Gotami, the aunt and foster mother of Buddha, was the first bhikkhuni; she was ordained in the sixth century BCE.[38][39]

Prajñādhara is the twenty-seventh Indian Patriarch of Zen Buddhism and is believed to have been a woman.[40]

In the Mahayana tradition during the 13th century, the Japanese Mugai Nyodai became the first female Zen master in Japan.[41]

However, the bhikkhuni ordination once existing in the countries where Theravada is more widespread died out around the 10th century, and novice ordination has also disappeared in those countries. Therefore, women who wish to live as nuns in those countries must do so by taking eight or ten precepts. Neither laywomen nor formally ordained, these women do not receive the recognition, education, financial support or status enjoyed by Buddhist men in their countries. These "precept-holders" live in Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, and Thailand. In particular, the governing council of Burmese Buddhism has ruled that there can be no valid ordination of women in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree. However, in 2003, Saccavadi and Gunasari were ordained as bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, thus becoming the first female Burmese novices in modern times to receive higher ordination in Sri Lanka.[42][43] Japan is a special case as, although it has neither the bhikkhuni nor novice ordinations, the precept-holding nuns who live there do enjoy a higher status and better training than their precept-holder sisters elsewhere, and can even become Zen priests.[44] In Tibet there is currently no bhikkhuni ordination, but the Dalai Lama has authorized followers of the Tibetan tradition to be ordained as nuns in traditions that have such ordination.

The bhikkhuni ordination of Buddhist nuns has always been practiced in East Asia.[45] In 1996, through the efforts of Sakyadhita, an International Buddhist Women Association, ten Sri Lankan women were ordained as bhikkhunis in Sarnath, India.[46] Also, bhikkhuni ordination of Buddhist nuns began again in Sri Lanka in 1998 after a lapse of 900 years.[47] In 2003 Ayya Sudhamma became the first American-born woman to receive bhikkhuni ordination in Sri Lanka.[37] Furthermore, on February 28, 2003, Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, formerly known as Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, became the first Thai woman to receive bhikkhuni ordination as a Theravada nun (Theravada is a school of Buddhism).[48] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni was ordained in Sri Lanka.[49] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni's mother Venerable Voramai, also called Ta Tao Fa Tzu, had become the first fully ordained Thai woman in the Mahayana lineage in Taiwan in 1971.[50][51]

A 55-year-old Thai Buddhist 8-precept white-robed maechee nun, Varanggana Vanavichayen, became the first woman ordained as a monk in Thailand, in 2002.[52] Since then, the Thai Senate has reviewed and revoked the secular law passed in 1928 banning women's full ordination in Buddhism as unconstitutional for being counter to laws protecting freedom of religion. However Thailand's two main Theravada Buddhist orders, the Mahanikaya and Dhammayutika Nikaya, have yet to officially accept fully ordained women into their ranks.

In 2009 in Australia four women received bhikkhuni ordination as Theravada nuns, the first time such ordination had occurred in Australia.[53] It was performed in Perth, Australia, on 22 October 2009 at Bodhinyana Monastery. Abbess Vayama together with Venerables Nirodha, Seri, and Hasapanna were ordained as Bhikkhunis by a dual Sangha act of Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis in full accordance with the Pali Vinaya.[54]

In 1997 Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston was founded by Ven. Gotami of Thailand, then a 10 precept nun; when she received full ordination in 2000, her dwelling became America's first Theravada Buddhist bhikkhuni vihara. In 1998 Sherry Chayat, born in Brooklyn, became the first American woman to receive transmission in the Rinzai school of Buddhism.[55][56][57] In 2006 Merle Kodo Boyd, born in Texas, became the first African-American woman ever to receive Dharma transmission in Zen Buddhism.[58] Also in 2006, for the first time in American history, a Buddhist ordination was held where an American woman (Sister Khanti-Khema) took the Samaneri (novice) vows with an American monk (Bhante Vimalaramsi) presiding. This was done for the Buddhist American Forest Tradition at the Dhamma Sukha Meditation Center in Missouri.[59] In 2010 the first Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in America (Vajra Dakini Nunnery in Vermont) was officially consecrated. It offers novice ordination and follows the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism. The abbot of the Vajra Dakini nunnery is Khenmo Drolma, an American woman, who is the first bhikkhuni in the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism, having been ordained in Taiwan in 2002.[60][61] She is also the first westerner, male or female, to be installed as an abbot in the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism, having been installed as the abbot of the Vajra Dakini Nunnery in 2004.[60] The Vajra Dakini Nunnery does not follow The Eight Garudhammas.[62] Also in 2010, in Northern California, four novice nuns were given the full bhikkhuni ordination in the Thai Theravada tradition, which included the double ordination ceremony. Bhante Gunaratana and other monks and nuns were in attendance. It was the first such ordination ever in the Western hemisphere.[63] The following month, more bhikkhuni ordinations were completed in Southern California, led by Walpola Piyananda and other monks and nuns. The bhikkhunis ordained in Southern California were Lakshapathiye Samadhi (born in Sri Lanka), Cariyapanna, Susila, Sammasati (all three born in Vietnam), and Uttamanyana (born in Myanmar).[64]

The first bhikkhuni ordination in Germany, the Theravada bhikkhuni ordination of German nun Samaneri Dhira, occurred on June 21, 2015, at Anenja Vihara.[65]

The first Theravada ordination of bhikkhunis in Indonesia after more than a thousand years occurred in 2015 at Wisma Kusalayani in Lembang, Bandung.[66] Those ordained included Vajiradevi Sadhika Bhikkhuni from Indonesia, Medha Bhikkhuni from Sri Lanka, Anula Bhikkhuni from Japan, Santasukha Santamana Bhikkhuni from Vietnam, Sukhi Bhikkhuni and Sumangala Bhikkhuni from Malaysia, and Jenti Bhikkhuni from Australia.[66]

The official lineage of Tibetan Buddhist bhikkhunis recommenced on 23 June 2022 in Bhutan when 144 nuns, most of them Butanese, were fully ordained.[67][68]

Christianity

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

In the liturgical traditions of Christianity, including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, Lutheranism and Anglicanism, the term ordination refers more narrowly to the means by which a person is included in one of the orders of bishops, priests or deacons. Among these historic branches of Christianity, the episcopacy and priesthood have been reserved for men, although some argue that women have served as deacons in their own right and as apostles, though this is disputed by the Roman Catholic and other historic Christian churches.[69][70] This is distinguished from the process of consecration to religious orders, namely nuns and monks, which are typically open to women and men. Some Protestant denominations understand ordination more generally as the acceptance of a person for pastoral work.

Historians Gary Macy, Kevin Madigan and Carolyn Osiek report having identified documented instances of ordained women in the early Church.[71][5] In 2021, excavations at the site of a 1600-year-old Byzantine basilica revealed mosaics that provided evidence of women serving primarily as diaconal ministers in early Christendom, although there has been speculation of other females in ministry as leaders of convents.[72] Additionally, Paul's letter to the Romans, written in the first century AD, mentions a woman deacon:

I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church in Cenchreae.

— Romans 16:1, New International Version, [73]

In the late second century AD, the Montanist movement ordained women priests and bishops.[8][74][75]

In 494 AD, in response to reports that women were serving at the altar in the south of Italy, Pope Gelasius I wrote a letter condemning female participation in the celebration of the Eucharist.[5] However, according to O'Brien, he never specified the scriptural or theological foundation for restricting priesthood to men only.[76] Several textual ambiguities and silences have resulted in a variety of contrasting interpretations.[77] Roger Gryson asserts that it is "difficult to form an idea of the situation which Pope Gelasius opposed" and observes that "it is regrettable that more details" about the situation are not available.[78]

The Protestant Reformation introduced the dogma that the authority of the Bible exceeds that of Roman Catholic popes and other church figures. Once the Roman Catholic hierarchy was no longer accepted as the sole authority, some denominations allowed women to preach. For example, George Fox founded the Quaker movement after stating he felt the "inner light" of Christ living in the believer was discovered in 1646.[79] He believed that the inner light worked in women as well as in men, and said:

And some men may say, man must have the power and superiority over the woman, because God says, "The man must rule over his wife [Genesis 3:16]; and that man is not of the woman, but the woman is of the man [1 Corinthians 11:8]." Indeed, after man fell, that command was; but before man fell there was no such command; for they were both meet-helps [Genesis 2:18,20], and they were both to have dominion over all that God made [Genesis 1:26,28]. And as the apostle saith, "for as the woman is of the man", his next words are, "so is the man also by the woman; but all things are of God [1 Corinthians 11:12]". And so the apostle clears his own words; and so as man and woman are restored again, by Christ up into the image of God [Colossians 3:10], they both have dominion again in the righteousness and holiness [Ephesians 4:24], and are helps-meet, as before they fell.

— George Fox, [80]

The ordination of women has once again been a controversial issue in more recent years with societal focus on social justice movements.[7] Still, some Christians believe in an interpretation of the New Testament which would promote a division between roles of men and women in the Christian Church.[81][4] Evangelical Christians who place emphasis on the infallibility of the Bible base their opposition to women's ordination as deacons and pastors partly upon the writings of the Apostle Paul, such as Ephesians 5:23,[82] 1 Timothy 2:11–15,[83] and 1 Timothy 3:1–7,[84] which they interpret as demanding male leadership in the Church.[85][86] Some Evangelicals also look to the levitical priesthood and historic rabbinate, being male only.[87] Other evangelical denominations officially authorize the full ordination of women in churches.[88][89] Catholics may allude to Jesus Christ's choice of disciples as evidence of his intention for an exclusively male apostolic succession, as laid down by early Christian writers such as Tertullian and reiterated in the 1976 Vatican Declaration on the Question of the Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood.[90]

Supporters of women's ordination interpret the above-mentioned New Testament texts as being specific to certain social and church contexts and locations and addressing problems of church order in the early Church period.[91] They regard Jesus as setting the example of treating women with respect, commending their faith and tasking them to tell others about him and Paul as treating women as his equals and co-workers.[91][92] They point to notable female figures in the Bible such as Phoebe, Junia (considered an apostle by Paul) and others in Romans 16:1,[93] the female disciples of Jesus, and the women at the crucifixion who were the first witnesses to the Resurrection of Christ,[94][95] as supporting evidence of the importance of women as pastoral or episcopal leaders in the early Church.[92][96][97]

Roman Catholic

[edit]The teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, as emphasized by Pope John Paul II in the apostolic letter Ordinatio sacerdotalis, is "that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgement is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful".[98]

This teaching is embodied in the current canon law (1024)[99] and the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), by the canonical statement: "Only a baptized man (Latin: vir) validly receives sacred ordination."[100] Insofar as priestly and episcopal ordination are concerned, the Roman Catholic Church teaches that this requirement is a matter of divine law; it belongs to the deposit of faith and is unchangeable.[101][102][103]

In 2007, the Holy See issued a decree stating that attempted ordination of a woman would result in automatic excommunication for the women and bishops attempting to ordain them,[104] and in 2010, that attempted ordination of women is a "grave delict".[105]

An official Papal Commission ordered by Pope Francis in 2016 was charged with determining whether the ancient practice of having female deacons (deaconesses) is possible, provided they are non-ordained and that certain reserved functions of ordained male permanent or transitional deacons—proclaiming the Gospel at Mass, giving a homily, and performing non-emergency baptisms—would not be permitted for the discussed female diaconate. In October 2019, the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region called for "married priests, pope to reopen women deacons commission."[106] Pope Francis later omitted discussion of the issue from the ensuing documents.[107]

Dissenters

[edit]Various Catholics have written in favor of ordaining women.[108] Dissenting groups advocating women's ordination in opposition to Catholic teaching include Women's Ordination Worldwide,[109] Catholic Women's Ordination,[110] Roman Catholic Womenpriests,[111] and Women's Ordination Conference.[112] Some cite the alleged ordination of Ludmila Javorová in Communist Czechoslovakia in 1970 by Bishop Felix Davídek (1921–1988), himself clandestinely consecrated due to the shortage of priests caused by state persecution, as a precedent.[113] The Catholic Church treats attempted ordinations of women as invalid and automatically excommunicates all participants.[114]

Mariavites

[edit]

Inspired by a mystically inclined nun, Feliksa Kozłowska, the Mariavite movement originally began as a response to the perceived corruption of the Roman Catholic Church in the Russian Partition of 19th century Poland. The Mariavites, so named for their devotion to the Virgin Mary, attracted numerous parishes across Mazovia and the region around Łódź and at their height numbered some 300,000 people. Fearing a schism, the established church authorities asked for intervention from the Vatican. The Mariavites were eventually excommunicated by Papal Bull in 1905 and 1906. Their clergy, cut loose from the Catholic Church, found sanctuary with the Old Catholic Church and in 1909 the first Mariavite bishop, Michael Kowalski, was consecrated in Utrecht. Twenty years later, the now constituted Mariavite Church was riven by policy differences and a leadership struggle. Nevertheless, Archbishop Kowalski ordained the first 12 nuns as priests in 1929. He also introduced priestly marriage. The split in the church took effect, in part, over the place of the feminine in theology and the role of women in the life of the church. By 1935, Kowalski had introduced a "universal priesthood" that extended the priestly office to selected members of the laity. The two Mariavite churches survive to this day. The successors of Kowalski, who are known as the Catholic Mariavite Church and are based in the town of Felicjanów in the Płock region of Poland, are headed by a bishop who is a woman, although their numbers are dwarfed by the adherents of the more conventionally patriarchal Mariavites of Płock.[115]

Eastern Orthodox

[edit]The Eastern Orthodox Church follows a line of reasoning similar to that of the Roman Catholic Church with respect to the ordination of bishops and priests, and does not allow women's ordination to those orders.[116]

Thomas Hopko and Evangelos Theodorou have contended that female deacons were fully ordained in antiquity.[117] K. K. Fitzgerald has followed and amplified Theodorou's research. Metropolitan Kallistos Ware wrote:[6]

The order of deaconesses seems definitely to have been considered an "ordained" ministry during early centuries in at any rate the Christian East. [...] Some Orthodox writers regard deaconesses as having been a "lay" ministry. There are strong reasons for rejecting this view. In the Byzantine rite the liturgical office for the laying-on of hands for the deaconess is exactly parallel to that for the deacon; and so on the principle lex orandi, lex credendi—the Church's worshipping practice is a sure indication of its faith—it follows that the deaconesses receives, as does the deacon, a genuine sacramental ordination: not just a χειροθεσια (chirothesia) but a χειροτονια (chirotonia).

On October 8, 2004, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece voted to permit the appointment of monastic deaconesses—women to minister and assist at the liturgy within their own monasteries. The document however does not use the term χειροτονία, 'ordination', although the rites that are to be used are rites of ordination of clergy.[118][119][120][121]

Protestant

[edit]A justification given by many Protestants for female ministry is the fact that Mary Magdalene was chosen by Jesus to announce his resurrection to the apostles.[122]

A key theological doctrine for Reformed and most other Protestants is the priesthood of all believers—a doctrine considered by them so important that it has been dubbed by some as "a clarion truth of Scripture":[123]

This doctrine restores true dignity and true integrity to all believers since it teaches that all believers are priests and that as priests, they are to serve God—no matter what legitimate vocation they pursue. Thus, there is no vocation that is more "sacred" than any other. Because Christ is Lord over all areas of life, and because His word applies to all areas of life, nowhere does His Word even remotely suggest that the ministry is "sacred" while all other vocations are "secular". Scripture knows no sacred-secular distinction. All of life belongs to God. All of life is sacred. All believers are priests.

— David Hagopian. Trading Places: The Priesthood of All Believers[123]

Most Protestant denominations require pastors, ministers, deacons, and elders to be formally ordained. The early Protestant reformer Martin Bucer, for instance, cited Ephesians 4[124] and other Pauline letters in support of this.[125] While the process of ordination varies among the denominations and the specific church office to be held, it may require preparatory training such as seminary or Bible college, election by the congregation or appointment by a higher authority, and expectations of a lifestyle that requires a higher standard. For example, the Good News Translation of James 3:1 says, "My friends, not many of you should become teachers. As you know, we teachers will be judged with greater strictness than others."[126]

Usually, these roles were male preserves. However, Quakers, who have no ordained clergy, have had women preachers and leaders from their founding in the mid-17th century.[127] Women's ministry has been part of Methodist tradition in the UK for over 200 years. In the late 18th century in England, John Wesley allowed for female office-bearers and preachers.[128] The Salvation Army has allowed the ordination of women since its beginning in 1865, although it was a hotly disputed topic between William and Catherine Booth.[129] The fourth, thirteenth, and nineteenth Generals of the Salvation Army were women.[130] Similarly, the Church of the Nazarene has ordained women since its foundation in 1908, at which time a full 25% of its ordained ministers were women.[131]

Many Protestant denominations are committed to congregational governance and reserve the power to ordain ministers to local congregations. Because of this, if there is no denomination-wide prohibition on ordaining women, congregations may do so while other congregations of the same denomination might not consider doing likewise.

Since the 20th century an increasing number of Protestant Christian denominations have begun ordaining women. The Church of England appointed female lay readers during the First World War. Later the United Church of Canada in 1936 (Lydia Emelie Gruchy) and the American United Methodist Church in 1956 also began to ordain women.[132][133] The first female Moderator of the United Church of Canada—a position open to both ministers and laypeople—was the Rev. Lois Miriam Wilson, who served 1980–1982.

In 1918, Alma Bridwell White, head of the Pillar of Fire Church, became the first woman to be ordained bishop in the United States.[134][135]

Today, over half of all American Protestant denominations ordain women,[136] but some restrict the official positions a woman can hold. For instance, some ordain women for the military or hospital chaplaincy but prohibit them from serving in congregational roles. Over one-third of all seminary students (and in some seminaries nearly half) are female.[137][138]

Church of the Nazarene

[edit]The Church of the Nazarene has ordained women since its foundation as a denomination in 1908, at which time fully 25% of its ordained ministers were women. According to the Church of the Nazarene Manual, "The Church of the Nazarene supports the right of women to use their God-given spiritual gifts within the church, affirms the historic right of women to be elected and appointed to places of leadership within the Church of the Nazarene, including the offices of both elder and deacon."[131]

Lutheranism

[edit]The Church of Denmark became the first Lutheran body to ordain women in 1948. The largest Lutheran churches in the United States and Canada, The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada (ELCIC), have been ordaining women since 1970. The Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, which also encompasses the Lutheran Church-Canada, does not ordain women; neither do the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod or the Evangelical Lutheran Synod. The first local woman cleric ordained in the Holy Land was Sally Azar of the Lutheran church in 2023.[139]

Anglican

[edit]In 1917 the Church of England licensed women as lay readers called bishop's messengers, many of whom ran churches, but did not go as far as to ordain them.

From 1930 to 1978 the Anglican Group for the Ordination of Women to the Historic Ministry promoted the ordination of women in the Church of England.[140]

Within Anglicanism the majority of provinces now ordain women as deacons and priests.[141]

The first three women ordained as priests in the Anglican Communion were in Hong Kong: Li Tim-Oi in 1944 and Jane Hwang and Joyce M. Bennett in 1971.

On July 29, 1974, Bishops Daniel Corrigan, Robert L. DeWitt, and Edward R. Welles II of the U.S. Episcopal Church, with Bishop Antonio Ramos of Costa Rica, ordained eleven women as priests in a ceremony that was widely considered "irregular" because the women lacked "recommendation from the standing committee", a canonical prerequisite for ordination. The "Philadelphia Eleven", as they became known, were Merrill Bittner, Alison Cheek, Alla Bozarth (Campell), Emily C. Hewitt, Carter Heyward, Suzanne R. Hiatt (d. 2002), Marie Moorefield, Jeannette Piccard (d. 1981), Betty Bone Schiess, Katrina Welles Swanson (d. 2006), and Nancy Hatch Wittig.[142] Initially opposed by the House of Bishops, the ordinations received approval from the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in September 1976. This General Convention approved the ordination of women to both the priesthood and the episcopate.

Reacting to the action of the General Convention, clergy and laypersons opposed to the ordination of women to the priesthood met in convention at the Congress of St. Louis and attempted to form a rival Anglican church in the US and Canada. Despite the plans for a united North American church, the result was division into several Continuing Anglican churches, which now make up part of the Continuing Anglican movement.

The first woman to become a bishop in the Anglican Communion was Barbara Harris, who was elected a suffragan bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts in 1988 and ordained on February 11, 1989. The majority of Anglican provinces now permit the ordination of women as bishops,[141][143] and as of 2014, women have served or are serving as bishops in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, South Africa, South India, Wales, and in the extra provincial Episcopal Church of Cuba.

In the Church of England, Libby Lane became the first woman consecrated a bishop in 2015.[144] It had ordained 32 women as its first female priests in March 1994.[145] In 2015 Rachel Treweek was consecrated as the first female diocesan bishop in the Church of England (Diocese of Gloucester).[146] She and Sarah Mullally, Bishop of Crediton, were the first women to be consecrated and ordained bishop in Canterbury Cathedral.[146] Also that year Treweek became the first woman to sit in the House of Lords as a Lord Spiritual, thus making her at the time the most senior ordained woman in the Church of England.[147]

On June 18, 2006, the Episcopal Church became the first Anglican province to elect a woman, the Most Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori, as a primate (leader of an Anglican province), called the "Presiding Bishop" in the United States.[148]

Methodism

[edit]Methodist views on the ordination of women in the rite of holy orders are diverse.

Today some Methodist denominations practice the ordination of women, such as in the United Methodist Church (UMC), in which the ordination of women has occurred since its creation in 1968, as well as in the Free Methodist Church (FMC), which ordained its first woman elder in 1911,[149] in the Methodist Church of Great Britain, which ordained its first female deacon in 1890 and ordained its first female elders (that is, presbyters) in 1974,[150] and in the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection, which ordained its first female elder in 1853,[151] as well as the Bible Methodist Connection of Churches, which has always ordained women to the presbyterate and diaconate.[152]

Other Methodist denominations do not ordain women, such as the Southern Methodist Church (SMC), Evangelical Methodist Church of America, Fundamental Methodist Conference, Evangelical Wesleyan Church (EWC), and Primitive Methodist Church (PMC), the latter two of which do not ordain women as elders nor do they license them as pastors or local preachers;[153][154] the EWC and PMC do, however, consecrate women as deaconesses.[153][154] Independent Methodist parishes that are registered with the Association of Independent Methodists do not permit the ordination of women to holy orders.

Religious Society of Friends

[edit]From their founding in the mid-17th century, Quakers have allowed women to preach.[155] They believed that both genders are equally capable of inspiration by the Holy Spirit and thus there is a tradition of women preachers in Quaker Meetings from their earliest days.[156] In order to be a preacher, a Friend had to obtain recognition by a Quaking Meeting. In the 18th century, ministers typically sat at the front of the meeting house, with women on one side and men on the other, all on the same raised platform.[156]

Women ministers were active from the earliest days. In 1657, Mary Howgill, one of the Valiant Sixty (an early group of Quaker preachers), rebuked Oliver Cromwell for persecuting Quakers, saying, "When thou givest account of all those actions, which have been acted by thee, [...] as my soul lives, these things will be laid to thy charge."[157] Later, in 1704, Esther Palmer of Flushing, Long Island, and Susanna Freeborn of Newport, Rhode Island, set out on a 3,230 mile journey across eight colonies of North America, including visits to preach in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.

Other well-known Quaker women preachers were Mary Lawson of Philadelphia, Mary Bannister of London, England, Mary Ellerton of York, England, Rachel Wilson of Virginia, Catharine Payton of Pennsylvania, Ann Moore of New York, Susanna Hatton of Delaware, and Mary Dyer of Boston.[156]

Baptist

[edit]American Clarissa Danforth, a member of the Free Will Baptist tradition, was ordained a pastor in 1815, being the first woman Baptist pastor.[158] Other ordinations of women pastors took place thereafter. In 1882 in the American Baptist Churches USA,[159] in 1922 in the Baptist Union of Great Britain,[160] in 1965 in the National Baptist Convention, USA,[161] in 1969 in the Progressive National Baptist Convention,[160] in 1978 in the Australian Baptist Ministries,[162] and in 1980 in the Convention of Philippine Baptist Churches.[162]

Pentecostal

[edit]The Assemblies of God of the United States accepted women's ordination in 1927.[163]: 46 In 1975, the ordination of women began in the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, founded by female evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson.[163]: 55 As Pentecostal churches are often independent, there is a variety of differing positions on the issue, with some of them appointing women as pastors and in other missional roles, and others not.

Seventh-day Adventist

[edit]According to its Working Policy, the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Church restricts certain positions of service and responsibility to those who have been ordained to the gospel ministry. The General Conference (GC) in session, the highest decision-making body of the church, has never approved the ordination of women as ministers, despite the significant foundational role and ongoing influence of a woman, Ellen G. White. Adventists have found no clear mandate or precedent for or against the practice of ordaining women in Scripture or in White's writings. In recent years the ordination of women has been the subject of heated debate, especially in North America and Europe. In the Adventist church, candidates for ordination are recommended by local conferences (which usually administer 50–150 local congregations) and approved by union conferences (which administer 6–12 local conferences). The church's Fundamental Beliefs and its worldwide practice as set forth in its Church Manual, including the worldwide qualifications for ordination currently restricted to men, can be revised only at a GC session.

In 1990, the GC session voted against a motion to establish a worldwide policy permitting the ordination of women.[164] In 1995, GC delegates voted not to authorize any of the 13 world divisions to establish policies for ordaining women within its territory.[164] After a delegate at the 2010 GC session recommended it, the GC administration on September 20, 2011 established the Theology of Ordination Study Committee, which included representatives from each of its 13 world division biblical research committees, to study the issue and prepare a recommendation for 2015 GC session.[165] In October 2011 at its Annual Council meeting, the GC Executive Committee voted 167–117 against a request from the North American Division (NAD)—supported by the Trans-European Division—to permit persons (including women) with commissioned minister credentials to serve as local conference presidents.[166] Later that month, the NAD ignored the GC action and voted to permit women with commissioned minister credentials to serve as conference presidents.[167]

In the wake of the Annual Council vote, a small group of Adventists in the Southeastern California Conference (SECC) organized the Ordination Political Action Committee (OPAC) with the goal of bringing political pressure on the SECC leadership to unilaterally adopt the policy of pastoral ordination without regard to gender. The group launched the OPAC on January 1, 2012 with the stated intention of achieving its objective by March 31, 2012. After creating a comprehensive web site, a widely distributed petition, and a presence on various social media platforms and after holding multiple meetings with various groups, including SECC officials, the OPAC reached its goal on March 22, 2012, when the SECC Executive voted 19–2 to immediately implement the policy of ordaining pastors without regard to gender.[168]

Meanwhile, early in 2012, the GC issued an analysis of church history and policy, demonstrating that worldwide divisions of the GC do not have the authority to establish policy different from that of the GC.[169] However, in their analysis, the GC confirmed that the "final responsibility and authority" for approving candidates for ordination resides at the union conference level. Several union conferences subsequently voted to approve ordinations without regard to gender.

After achieving its initial objective in the SECC, the OPAC shifted its focus to the Pacific Union Conference (PUCon), which, by policy, must review and act on all ordination recommendations from its local conferences. For many years the PUCon had supported the concept of ordaining women pastors. It took up the matter again on March 15, 2012 but tabled any action until May 9, 2012, when it voted 42–2 to begin processing ministerial ordinations without regard to gender as soon as it could amend its bylaws. The vote also included the call for a constituency meeting on August 19, 2012, when it would consider such a bylaws change.[170] The PUCon constituents voted 79% (334–87) to support this recommendation and amend the bylaws accordingly.[171] Some local conferences within the PUCon began to implement the new policy immediately.[172] By mid-2013, about 25 women had been ordained to the ministry in the Pacific Union Conference.

Stimulated at least in part by the international reach of the OPAC and even before it achieved its ultimate objective with the PUCon, other church administrative entities took similar actions. On April 23, 2012, the North German Union voted to ordain women as ministers[173] but by late 2013 had not yet ordained a woman. On July 29, 2012, the Columbia Union Conference voted to "authorize ordination without respect to gender".[174] On May 12, 2013, the Danish Union voted to treat men and women ministers the same and to suspend all ordinations until after the topic would be considered at the next GC session in 2015. On May 30, 2013, the Netherlands Union voted to ordain female pastors, recognizing them as equal to their male colleagues[175] and ordained its first female pastor on September 1, 2013.[176] When Sandra Roberts was elected president of the SECC on October 27, 2013,[177] she became the first SDA woman to serve as president of a local conference, However, the GC never recognized her in that role.[d] Eight years later, Roberts was elected executive secretary of the Pacific Union Conference on August 16, 2021.[178] On September 12, 2021, the Mid-America Union Conference Constituency voted 82% to authorize the ordination of women in ministry, becoming the third union conference in the NAD to do so.[179]

At the 60th GC session in San Antonio on July 8, 2015,[180] Seventh-day Adventists voted not to permit regional church bodies to ordain women pastors.[181] The President of the GC, Ted N. C. Wilson, opened the morning session on the day of the vote with an appeal for all church members to abide by the vote's outcome and underscored before and after the vote that decisions made by the GC in session carry the highest authority in the Adventist Church. Prior to the GC vote, dozens of delegates spoke for and against the question: "After your prayerful study on ordination from the Bible, the writings of Ellen G. White, and the reports of the study commissions; and after your careful consideration of what is best for the church and the fulfillment of its mission, is it acceptable for division executive committees, as they may deem it appropriate in their territories, to make provision for the ordination of women to the gospel ministry?"[182] By secret ballot, the delegates passed the motion 1,381 to 977, with 5 abstentions, thus ending a five-year study process characterized by open, vigorous, and, sometimes, acrimonious debate.[182]

Philippine Independent Church

[edit]The Philippine Independent Church is an independent Catholic church in the Philippines founded in 1902. It has approved women's ordination since 1996. In 1997, it ordained its first female priest in the person of Rev. Rosalina Rabaria. As of 2017[update], it has 30 women priests and 9 women deacons. On May 5, 2019, the church consecrated its first female bishop in the person of The Right Reverend Emelyn G. Dacuycuy and installed her as an ordinary of Batac Diocese, Ilocos Norte. According to Obispo Maximo XIII Rhee Timbang, the ordination of women has enabled the church to become more relevant to its time and to society.

Jehovah's Witnesses

[edit]Jehovah's Witnesses consider qualified public baptism to represent the baptizand's ordination, following which he or she is immediately considered an ordained minister. In 1941, the Supreme Court of Vermont recognized the validity of this ordination for a female Jehovah's Witness minister.[183] The majority of Witnesses actively preaching from door to door are female.[184] Women are commonly appointed as full-time ministers, either to evangelize as "pioneers" or missionaries, or to serve at their branch offices.[185] Nevertheless, Witness deacons ("ministerial servants") and elders must be male, and only a baptized adult male may perform a Jehovah's Witness baptism, funeral, or wedding.[186] Within the congregation, a female Witness minister may only lead prayer and teaching when there is a special need, and must do so wearing a head covering.[187][188][189]

Mormonism

[edit]Community of Christ

[edit]The Community of Christ adopted the practice of women's ordination in 1984,[190] which was one of the reasons for the schism between the Community of Christ and the newly formed Restoration Branches movement, which was largely composed of members of the Community of Christ church (then known as the RLDS church) who refused to accept this development and other doctrinal changes taking place during this same period. For example, the Community of Christ also changed the name of one of its priesthood offices from evangelist-patriarch to evangelist, and its associated sacrament, the patriarchal blessing, to the evangelist's blessing. In 1998, Gail E. Mengel and Linda L. Booth became the first two women apostles in the Community of Christ.[191] At the 2007 World Conference of the church, Becky L. Savage was ordained as the first woman to serve in the First Presidency.[192][193] In 2013, Booth became the first woman elected to serve as president of the Council of Twelve.[194]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

[edit]The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) does not ordain women.[195] Some (most notably former LDS Church members D. Michael Quinn and Margaret Toscano) have argued that the church ordained women in the past and that therefore the church currently has the power to ordain women and should do so;[196][197] however, there are no known records of any women having been ordained to the priesthood.[198] Women do hold a prominent place in the church, including their work in the Relief Society, which is one of the largest and longest-lasting women's organizations in the world.[199] Women thus serve, as do men, in unpaid positions involving teaching, administration, missionary service, humanitarian efforts, and other capacities.[200] Women often offer prayers and deliver sermons during Sunday services. Ordain Women, an activist group of mostly LDS Church women founded by feminist Kate Kelly in March 2013, supports extending priesthood ordinations to women.[201]

Liberal Catholic

[edit]Of all the churches in the Liberal Catholic movement, only the original church, the Liberal Catholic Church under Bishop Graham Wale, does not ordain women. The position held by the Liberal Catholic Church is that the Church, even if it wanted to ordain women, does not have the authority to do so and that it would not be possible for a woman to become a priest even if she went through the ordination ceremony. The reasoning behind this belief is that the female body does not effectively channel the masculine energies of Christ, the true minister of all the sacraments. The priest has to be able to channel Christ's energies to validly confect the sacrament; therefore the sex of the priest is a central part of the ceremony hence all priests must be male. When discussing the sacrament of Holy Orders in his book Science of the Sacraments, Second Presiding Bishop Leadbeater also opined that women could not be ordained; he noted that Christ left no indication that women can become priests and that only Christ can change this arrangement.

Old Catholic

[edit]On 19 February 2000, Denise Wyss became the first woman to be ordained as a priest in the Old Catholic Church.[202]

Hinduism

[edit]Female ascetics are referred as Sannyasinis, Yoginis, Brahmacharinis, Parivajikas, Pravrajitas, Sadhvis, Pravrajikas.[203]

Bhairavi Brahmani is a guru of Sri Ramakrishna. She initiated Ramakrishna into Tantra. Under her guidance, Ramakrishna went through sixty four major tantric sadhanas which were completed in 1863.[204]

Ramakrishna Sarada Mission is the modern 21st century monastic order for women. The order was conducted under the guidance of the Ramakrishna monks until 1959, at which time it became entirely independent. It currently has centers in various parts of India, and also in Sydney, Australia.

Furthermore, both men and women are Hindu gurus.[205] Shakti Durga, formerly known as Kim Fraser, was Australia's first female guru.[206]

Islam

[edit]Although Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders, the imam serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. There is a current controversy among Muslims on the circumstances in which women may act as imams—that is, lead a congregation in salat (prayer). Three of the four Sunni schools, as well as many Shia, agree that a woman may lead a congregation consisting of women alone in prayer, although the Maliki school does not allow this. According to all currently existing traditional schools of Islam, a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in salat (prayer). Some schools make exceptions for Tarawih (optional Ramadan prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars—including Al-Tabari (838–932), Abu Thawr (764–854), Al-Muzani (791–878), and Ibn Arabi (1165–1240)—considered the practice permissible at least for optional (nafila) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group. Islamic feminists have begun to protest this.

Women's mosques, called nusi, and female imams have existed since the 19th century in China and continue today.[207]

In 1994, Amina Wadud (an Islamic studies professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, born in the United States), became the first woman in South Africa to deliver the jum'ah khutbah (Friday sermon), which she did at the Claremont Main Road Mosque in Cape Town, South Africa.[208]

In 2004 20-year-old Maryam Mirza delivered the second half of the Eid al-Fitr khutbah at the Etobicoke mosque in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, run by the United Muslim Association.[209]

In 2004, in Canada, Yasmin Shadeer led the night 'Isha prayer for a mixed-gender (men as well as women praying and hearing the sermon) congregation.[210] This is the first recorded occasion in modern times where a woman led a congregation in prayer in a mosque.[210]

On March 18, 2005, Amina Wadud gave a sermon and led Friday prayers for a Muslim congregation consisting of men as well as women, with no curtain dividing the men and women.[211] Another woman, Suheyla El-Attar, sounded the call to prayer while not wearing a headscarf at that same event.[211] This was done in the Synod House of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York after mosques refused to host the event.[211] This was the first known time that a woman had led a mixed-gender Muslim congregation in prayer in American history.[211]

In April 2005, Raheel Raza, born in Pakistan, led Toronto's first woman-led mixed-gender Friday prayer service, delivering the sermon and leading the prayers of the mixed-gender congregation organized by the Muslim Canadian Congress to celebrate Earth Day in the backyard of the downtown Toronto home of activist Tarek Fatah.[212]

On July 1, 2005, Pamela Taylor, co-chair of the New York-based Progressive Muslim Union and a Muslim convert since 1986, became the first woman to lead Friday prayers in a Canadian mosque, and did so for a congregation of both men and women.[213] In addition to leading the prayers, Taylor also gave a sermon on the importance of equality among people regardless of gender, race, sexual orientation and disability.[213]

In October 2005, Amina Wadud led a mixed gender Muslim congregational prayer in Barcelona.[214][215]

In 2008, Pamela Taylor gave the Friday khutbah and led the mixed-gender prayers in Toronto at the UMA mosque at the invitation of the Muslim Canadian Congress on Canada Day.[216]

On 17 October 2008, Amina Wadud became the first woman to lead a mixed-gender Muslim congregation in prayer in the United Kingdom when she performed the Friday prayers at Oxford's Wolfson College.[217]

In 2010, Raheel Raza became the first Muslim-born woman to lead a mixed-gender British congregation through Friday prayers.[218]

In 2014, Afra Jalabi, a Syrian Canadian journalist and peace advocate delivered Eid ul-Adha khutbah at Noor cultural centre in Toronto, Canada.

Judaism

[edit]

While several women engaged in the Torah and Talmudic study associated with rabbinic study in the middle ages, women were not ordained until the twentieth century. A possible exception is Asenath Barzani[220] of Iraq, who is considered by some scholars as the first woman rabbi of Jewish history.[221] The title referred to Barzani by the Jews of Afghanistan was Tannit, the feminine equivalent of Tanna, the title for a Jewish sage of the early Talmudic rabbis.[222] According to some researchers, the origin of the Barzani story is the travelogue of Rabbi Petachiah of Regensburg.[223] Another exception is the female Hasidic rebbe, Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, also known as the Maiden of Ludmir, active in the 19th century.[224]

In 1935 Regina Jonas was ordained privately by a German rabbi and became the world's first female rabbi.[219] In the mid-20th century, American Jewish movements began ordaining women. Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi in Reform Judaism in 1972;[225] Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi in Reconstructionist Judaism in 1974;[226] Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi in Jewish Renewal in 1981;[227] Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi in Conservative Judaism in 1985;[228] and Tamara Kolton became the very first rabbi of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female rabbi) in Humanistic Judaism in 1999.[229] Women in Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, Renewal, and Humanistic Judaism are routinely granted semicha (ordination) on an equal basis with men.

In June 2009, Avi Weiss ordained Sara Hurwitz with the title "maharat" (an acronym of manhiga hilkhatit rukhanit Toranit[230]) rather than "Rabbi".[231][232] In February 2010, Weiss announced that he was changing Maharat to a more familiar-sounding title "Rabba".[233] The goal of this shift was to clarify Hurwitz's position as a full member of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale rabbinic staff. The change was criticised by both Agudath Yisrael and the Rabbinical Council of America, who called the move "beyond the pale of Orthodox Judaism".[234] Weiss announced amidst criticism that the term "Rabba" would not be used anymore for his future students. Also in 2009, Weiss founded Yeshivat Maharat, a school which "is dedicated to giving Orthodox women proficiency in learning and teaching Talmud, understanding Jewish law and its application to everyday life as well as the other tools necessary to be Jewish communal leaders". Maharat alumnae take a variety of titles upon ordination, including Maharat, Rabba, and Rabbanit.[235] In 2015, Lila Kagedan was ordained as Rabbi by that same organization, making her their first graduate to take the title Rabbi.[236] Hurwitz continues to use the title Rabba and is considered by some to be the first female Orthodox rabbi.[237][238][239]

In the fall of 2015 Rabbinical Council of America passed a resolution which states, "RCA members with positions in Orthodox institutions may not ordain women into the Orthodox rabbinate, regardless of the title used; or hire or ratify the hiring of a woman into a rabbinic position at an Orthodox institution; or allow a title implying rabbinic ordination to be used by a teacher of Limudei Kodesh in an Orthodox institution."[240] Similarly in the fall of 2015 Agudath Israel of America denounced moves to ordain women, and went even further, declaring Yeshivat Maharat, Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, Open Orthodoxy, and other affiliated entities to be similar to other dissident movements throughout Jewish history in having rejected basic tenets of Judaism.[241][242][243]

Only men can become cantors (also called hazzans) in most of Orthodox Judaism, but all other types of Judaism allow and have female cantors.[244] In 1955 Betty Robbins, born in Greece, became the world's first female cantor when she was appointed cantor of the Reform congregation of Temple Avodah in Oceanside, New York, in July.[245] Barbara Ostfeld-Horowitz became the first female cantor to be ordained in Reform Judaism in 1975.[246] Erica Lippitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel became the first female cantors in Conservative Judaism in 1987.[246] However, the Cantors Assembly, a professional organization of cantors associated with Conservative Judaism, did not allow women to join until 1990.[247] In 2001 Deborah Davis became the first cantor of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Humanistic Judaism, although Humanistic Judaism has since stopped graduating cantors.[248] Sharon Hordes became the first cantor of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Reconstructionist Judaism in 2002.[249] Avitall Gerstetter, who lives in Germany, became the first female cantor in Jewish Renewal (and the first female cantor in Germany) in 2002. Susan Wehle became the first American female cantor in Jewish Renewal in 2006; however, she died in 2009.[250] The first American women to be ordained as cantors in Jewish Renewal after Wehle's ordination were Michal Rubin and Abbe Lyons, both ordained on January 10, 2010.[251]

In 2019, Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance created an initiative to support the hiring of female Jewish spiritual leaders and has released a statement supporting the ordination and hiring of women with the title Rabbi at Orthodox synagogues.[252] Open Orthodox Jewish women can become cantors and rabbis.

Ryukyuan religion

[edit]The indigenous religion of the Ryukyuan Islands in Japan is led by female priests; this makes it the only known official mainstream religion of a society led by women.[253]

Shinto

[edit]

In Shintoism, Saiin (斎院, saiin?) were unmarried female relatives of the Japanese emperor who served as high priestesses at Ise Grand Shrine from the late 7th century until the 14th century. Ise Grand Shrine is a Shinto shrine dedicated to the goddess Amaterasu-ōmikami. Saiin priestesses were usually elected from royalty (内親王, naishinnō) such as princesses (女王, joō). In principle, Saiin remained unmarried, but there were exceptions. Some Saiin became consorts of the Emperor, called Nyōgo in Japanese. According to the Man'yōshū (The Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves), the first Saiō to serve at Ise Grand Shrine was Princess Ōku, daughter of Emperor Tenmu, during the Asuka period of Japanese history.

Female Shinto priests were largely pushed out of their positions in 1868.[254] The ordination of women as Shinto priests arose again during World War II.[255] See also Miko.

Sikhism

[edit]Sikhism does not have priests, which were abolished by Guru Gobind Singh, as the guru had seen that institution become corrupt in society during his time. Instead, he appointed the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, as his successor as Guru instead of a possibly fallible human. Due to the faith's belief in complete equality, women can participate in any religious function, perform any Sikh ceremony or lead the congregation in prayer.[256] A Sikh woman has the right to become a Granthi, Ragi, and one of the Panj Piare (five beloved) and both men and women are considered capable of reaching the highest levels of spirituality.[257]

Taoism

[edit]Taoists ordain both men and women as priests.[258] In 2009 Wu Chengzhen became the first female fangzhang (principal abbot) in Taoism's 1,800-year history after being enthroned at Changchun Temple in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, in China.[259] Fangzhang is the highest position in a Taoist temple.[259]

Wicca

[edit]In Wicca, as many women are ordained as men. Many traditions elevate the importance of women over that of men and women are frequently leaders of covens. Members are typically considered Priests and Priestesses when they are given the rite of Initiation within the coven, though some may choose to undergo additional training to become High Priestess who often has the final say in matters and who may choose who can be her High Priest. Some, who have gone through enough experience, may leave to create their own coven.[260][261][262]

Yoruba

[edit]

The Yoruba people of western Nigeria practice an indigenous religion with a religious hierarchy of priests and priestesses that dates to 800–1000 CE. Ifá Oracle priests and priestesses bear the titles Babalawo and Iyanifa respectively.[263] Priests and priestesses of the varied Orisha, when not already bearing the higher ranked oracular titles mentioned above, are referred to as babalorisa when male and iyalorisa when female.[264] Initiates are also given an Orisa or Ifá name that signifies under which deity they are initiated; for example a priestess of Oshun may be named Osunyemi and a priest of Ifá may be named Ifáyemi.

Zoroastrianism

[edit]Zoroastrian priests in India are required to be male.[265] However, women have been ordained in Iran and North America as mobedyars, meaning women mobeds (Zoroastrian priests).[266][267][268] In 2011 the Tehran Mobeds Anjuman (Anjoman-e-Mobedan) announced that for the first time in Iran and of the Zoroastrian communities worldwide, women had joined the group of mobeds (priests) in Iran as mobedyars (women priests); the women hold official certificates and can perform the lower-rung religious functions including initiating people into the religion.[266]

See also

[edit]- Buddhist feminism

- Christian views of women

- Christian feminism

- Deaconess

- Feminist theology

- Islamic feminism

- Jewish feminism

- List of ordained Christian women

- List of the first 32 women ordained as Church of England priests

- List of the first women ordained as priests in the Anglican Church of Australia in 1992

- Mormon feminism

- Ordination of women in Protestant denominations

- Timeline of women hazzans in America

- Timeline of women hazzans

- Timeline of women in religion

- Timeline of women in religion in the United States

- Timeline of women rabbis in America

- Timeline of women rabbis

- Women as imams

- Women as theological figures

- Women in the Bible

- Women in Judaism

- Women rabbis

Notes

[edit]- ^ The process by which a person is understood to be consecrated and set apart by God for the administration of various religious rites.

- ^ Except within the diaconate and early church movement known as Montanism.[5][6][7][8]

- ^ One title for a sacerdos of the Bona Dea was damiatrix, presumably from Damia, one of the names of Demeter and associated also with the Bona Dea.

- ^ The print editions of the Seventh-day Adventist Yearbook during Robert's presidency through 2021 included no name for president of the SESS ("President, ___.").

References

[edit]- ^ "US Episcopal Church installs first female presiding bishop". Australia: Journeyonline.com.au. 2006-11-07. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ a b "The divide over ordaining women". Pew Research Center. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ Turpin, Andrea (May 24, 2018). "Evangelicals have long disagreed on the role of women in the church". News Observer.

- ^ a b Green, Emma (2017-07-05). "This Is What a Battle Over Gender and Race Looks Like in a Conservative Christian Community". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ a b c Madigan, Kevin; Osiek, Carolyn, eds. (2005). Ordained Women in the Early Church: a Documentary History (pbk ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780801879326.

- ^ a b Ware, Kallistos (1999) [1982]. "Man, Woman and the Priesthood of Christ". In Hopko, Thomas (ed.). Women and the Priesthood (New ed.). Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780881411461. as quoted in Wijngaards, John (2006). Women deacons in the early church: historical texts and contemporary debates. New York: Herder & Herder. ISBN 0-8245-2393-8.

- ^ a b Chaves, Mark; Cavendish, James (1997). "Recent Changes in Women's Ordination Conflicts: The Effect of a Social Movement on Intraorganizational Controversy". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 36 (4): 574–584. doi:10.2307/1387691. ISSN 0021-8294. JSTOR 1387691.

- ^ a b Kienzle, Beverly Mayne; Walker, Professor Pamela J.; Walker, Pamela J. (1998-04-30). Women Preachers and Prophets Through Two Millennia of Christianity. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20922-0.

- ^ "Women bishops vote: Church of England 'resembles sect'". BBC News – UK Politics. BBC. 2012-11-22. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Sarah Dening (1996), The Mythology of Sex Archived 2010-09-01 at the Wayback Machine, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-02-861207-2. Ch.3.

- ^ Lindemann, Kate. "En HeduAnna (EnHedu'Anna) philosopher of Iraq – 2354 BC". Women-philosophers.com. Kate Lindemann, PhD. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ Plinio Prioreschi (1996). A History of Medicine: Primitive and ancient medicine. Horatius Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-888456-01-1. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Jeremy Black (1998), Reading Sumerian Poetry, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-485-93003-X. pp 142. Reading Sumerian poetry (pg. 142) Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Lexicon:: Strong's H6948 – qĕdeshah". Blue Letter Bible. Sowing Circle. Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Blue Letter Bible, Lexicon results for qĕdeshah (Strong's H2181), incorporating Strong's Concordance (1890) and Gesenius's Lexicon (1857).

- ^ Also transliterated qĕdeshah, qedeshah, qědēšā ,qedashah, kadeshah, kadesha, qedesha, kdesha.

- ^ Gillam, Robyn A. (1995). "Priestesses of Hathor: Their Function, Decline, and Disappearance". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 32. ARCE: 211–237. doi:10.2307/40000840. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000840.

- ^ Gerald Hovenden (2002-12-31). Speaking in Tongues: The New Testament Evidence in Context. Continuum. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-84127-306-8. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Lester L. Grabbe; Robert D. Haak (2003). "Introduction and Overview". Knowing the End From the Beginning: The Prophetic, Apocalyptic, and Their Relationship. Continuum. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-567-08462-0. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Ariadne Staples (January 1998). From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-13233-6. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ L. Richardson, jr (1992-10-01). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. JHU Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones (1986). The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: A Social Economic and Administrative Survey. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8018-3353-3. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Celia E. Schultz (2006-12-08). Women's Religious Activity in the Roman Republic. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 70–71, 79–81. ISBN 978-0-8078-7725-8. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ a b Lesley E. Lundeen (2006-12-14). "Chapter 2: In Search of the Etruscan priestess: a re-examination of the hatrencu". Religion in Republican Italy. Paul B. Harvey, Celia E. Schultz. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-139-46067-5. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Barbette Stanley Spaeth (1996). The Roman Goddess Ceres. University of Texas Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-292-77693-7. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres, pp. 4–5, 9, 20 (historical overview and Aventine priesthoods), 84–89 (functions of plebeian aediles), 104–106 (women as priestesses): citing among others Cicero, In Verres, 2.4.108; Valerius Maximus, 1.1.1; Plutarch, De Mulierum Virtutibus, 26.

- ^ Brouwer, Hendrik H. J. (1 June 1989). Bona Dea: The Sources and a Description of the Cult. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. Vol. 110. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08606-7. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

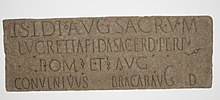

- ^ CIL II. 2416: Isidi Aug(ustae) sacrum/ Lucretia Fida sacerd(os) perp(etua)/ Rom(ae) et Aug(usti)/ conventu{u}s Bracar(a)aug(ustani) d(edit) ("Lucretia Fida, the priest-for-life of Roma and Augustus, from Conventus Bracarensis, Braga, has given a sacrum to Isis Augusta"), from the D. Diogo de Sousa Museum, Braga, Portugal.

- ^ Stephen L. Dyson (2010-08-01). Rome: A Living Portrait of an Ancient City. JHU Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4214-0101-0. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Rüpke, Jörg (13 August 2007). A Companion to Roman Religion'. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Vol. 29 (illustrated ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781405129435. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Jean MacIntosh Turfa, "Etruscan Religion at the Watershed: Before and After the Fourth Century BCE", in Religion in Republican Italy (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 48.

- ^ "Works by Chögyam Trungpa and His Students". Dharma Haven. June 23, 1999. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ "Ani Pema Chödrön". Gampoabbey.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), page 352

- ^ Book of the Discipline, Pali Text Society, volume V, Chapter X

- ^ Code, Lorraine, ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of feminist theories. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30885-4. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ a b "The Outstanding Women in Buddhism Awards". Owbaw.org. Archived from the original on 2011-01-14. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "The Life of the Buddha: (Part Two) The Order of Nuns". Buddhanet.net. Archived from the original on 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "A New Possibility". Congress-on-buddhist-women.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Austin, Shoshan Victoria (2012). "The True Human Body". In Carney, Eido Frances (ed.). Receiving the Marrow. Temple Ground Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0985565107.

- ^ "Abbess Nyodai's 700th Memorial". Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Saccavadi's story". Sujato's Blog. 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "The Story of One Burmese Nun – Tricycle". Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "Resources on Women's Ordination". Lhamo.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-06. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Bhikkhuni & Siladhara: Points of Comparison". Archived from the original on 2010-01-31. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Monica Lindberg Falk (2007). Making Fields of Merit: Buddhist Female Ascetics and Gendered Orders in Thailand. NIAS Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-87-7694-019-5. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- ^ Bhikkhuni Sobhana. "Contemporary bhikkuni ordination in Sri Lanka". Lakehouse.lk. Archived from the original on 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Ordained At Last". Thebuddhadharma.com. 2003-02-28. Archived from the original on February 6, 2004. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Rita C. Larivee, SSA (2003-05-14). "Bhikkhunis: Ordaining Buddhist Women". Nationalcatholicreporter.org. Archived from the original on 2018-10-23. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Queen, Christopher S.; King, Sallie B. (1996). Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791428443. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ^ "IPS – Thai Women Don Monks' Robes | Inter Press Service". Ipsnews.net. 2013-11-01. Archived from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ^ Sommer, PhD, Jeanne Matthew. "Socially Engaged Buddhism in Thailand: Ordination of Thai Women Monks". Warren Wilson College. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Thai monks oppose West Australian ordination of Buddhist nuns". Wa.buddhistcouncil.org.au. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Bhikkhuni Ordination". Dhammasara.org.au. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2011-02-19. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Article: First Female Rabbi in Belarus travels the Hinterlands: On the Road with Nelly Shulman". Highbeam.com. 2001-03-23. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Encyclopedia of women and religion in North America, Volume 2 Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine By Rosemary Skinner Keller, Rosemary Radford Ruether, Marie Cantlon (pg. 642)

- ^ "The Lost Lineage". Thebuddhadharma.com. Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ James Ishmael Ford (2006). Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen. Wisdom Publications. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-86171-509-1. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Background story for Sister Khema". Dhammasukha.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ^ a b "Women Making History". Vajradakininunnery.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-01. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Khenmo Drolma". Vajradakininunnery.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-01. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ "Vajra Dakini Nunnery". Vajra Dakini Nunnery. Archived from the original on 2010-05-07. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Boorstein, Sylvia (2011-05-25). "Ordination of Bhikkhunis in the Theravada Tradition". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2010-09-05. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ Dr. Stephen Long. "Bhikkhuni Ordination in Los Angeles". Asiantribune.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ^ Bhikkhuni Happenings – Alliance for Bhikkhunis Archived 2015-06-29 at the Wayback Machine. Bhikkhuni.net. Retrieved on 2015-06-28.

- ^ a b "First Theravada Ordination of Bhikkhunis in Indonesia After a Thousand Years" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- ^ Mackenzie, Vicki (22 July 2024). "Making the Sangha Whole". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

- ^ DAMCHÖ DIANA FINNEGAN and CAROLA ROLOFF (BHIKṢUṆĪ JAMPA TSEDROEN). "Women Receive Full Ordination in Bhutan For First Time in Modern History", Lion's Roar, JUNE 27, 2022.

- ^ "Women deacons in history". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Who is Junia?". OCA Department of Christian Education. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Macy, Gary (2008). The hidden history of women's ordination: female clergy in the medieval West. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780195189704.

- ^ David, Ariel. "Byzantine Basilica With Graves of Female Ministers and Baffling Mass Burials Found in Israel". Haaretz. Retrieved 2021-11-23.