Osraige

Ossory Osraige | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150[1]–1541 | |||||||||

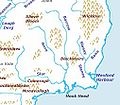

A map of Osraige in the 10th century. | |||||||||

| Capital | Kilkenny | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Irish, Middle Irish, Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Celtic polytheism (pre-432), Celtic Christianity (c. 432–1152), Roman Catholicism (c. 1152–present) | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| First and last Kings | |||||||||

• (eponymous founder) c. 150 AD | Óengus Osrithe | ||||||||

• (last king of major Osraige) d. 1194 | Maelseachlainn Mac Gilla Patráic[2] | ||||||||

• submitted 1537; ennobled 1541 | Brian Mac Giolla Phádraig | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Osraige | 150[1] | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1541 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Osraige,[3] also known as Osraighe or Ossory (modern Irish: Osraí), was a medieval Irish kingdom comprising most of present-day County Kilkenny and western County Laois. The home of the Osraige people, it existed from around the first century until the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. It was ruled by the Dál Birn dynasts, whose medieval descendants assumed the surname Mac Giolla Phádraig. The name survives in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Ossory, established in the 5th century, which continues to use roughly the same borders.

According to tradition, Osraige was founded by Óengus Osrithe in the 1st century and was originally within Leinster's polity. In the 5th century, the Corcu Loígde of Munster displaced the Dál Birn and brought Osraige under Munster's direct control. The Dál Birn returned to power in the 7th century, though Osraige remained nominally part of Munster until 859, when it achieved formal independence under the powerful king Cerball mac Dúnlainge. Osraige's rulers remained major players in Irish politics for the next three centuries, though they never vied for the High Kingship. In the early 12th century, dynastic infighting fragmented the kingdom, and it was re-adjoined to Leinster. The Normans under Strongbow invaded Ireland beginning in 1169, and most of Osraige collapsed under pressure from Norman leader William Marshal. The northern part of the kingdom, eventually known as Upper Ossory, survived intact under the hereditary lordship until the reign of King Henry VIII of England, when it was formally incorporated as a barony of the same name.

Geography

The ancient Osraige inhabited the fertile land around the River Nore valley, occupying nearly all of what is modern County Kilkenny and the western half of neighbouring County Laois. To the west and south, Osraige was bounded by the River Suir and what is now Waterford Harbour; to the east, the watershed of the River Barrow marked the boundary with Leinster (including Gowran); to the north, it extended into and beyond the Slieve Bloom Mountains. These three principal rivers- the Nore, the Barrow, and the Suir- which unite just north of Waterford City were collectively known as the "Three Sisters" (Irish: Cumar na dTrí Uisce).[4] Like many other Irish kingdoms, the tribal name of Osraighe also came to be applied to the territory they occupied; thus, wherever the Osraige dwelt became known as Osraige. The kingdom's most significant neighbours were the Loígsi, Uí Ceinnselaig and Uí Bairrche of Leinster to the north and east and the Déisi, Eóganacht Chaisil and Éile of Munster to the south and west.[5] Some of the highest points of land are Brandon Hill (County Kilkenny) and Arderin (on the Laois-Offaly border). The ancient Slige Dala[6] road ran southwest through northern Osraige from the Hill of Tara towards Munster;[7][8][9] which later gave its name to the medieval Ballaghmore Castle.[10] Another ancient road, the Slighe Cualann cut into southeast Osraige west of present-day Ross, before turning south to present-day Waterford city.

-

Topography of Osraige; note location of the "Three Sisters".

-

The source of the River Barrow in the Slieve Bloom Mountains

-

The River Nore

-

The River Suir

-

The Slieve Blooms

-

Cnoc Bhréanail, aka Brandon Hill, the highest elevation in Kilkenny

History

Origins and prehistory

The tribal name Osraige means "people of the deer", and is traditionally claimed to be taken from the name of the ruling dynasty's semi-legendary pre-Christian founder, Óengus Osrithe.[11][12] The Osraige were probably either a southern branch of the Ulaid or Dál Fiatach of Ulster,[13] or close kin to their former Corcu Loígde allies.[14] In either case it would appear they should properly be counted among the Érainn. Some scholars believe that the Ō pedigree of the Osraige is a fabrication, invented to help them achieve their goals in Leinster. Francis John Byrne suggests that it may date from the time of Cerball mac Dúnlainge.[15] The Osraighe themselves claimed to be descended from the Érainn people, although scholars propose that the Ivernic groups included the Osraige. Prior to the coming of Christianity to Ireland, the Osraige and their relatives the Corcu Loígde appear to have been the dominant political groups in Munster, before the rise of the Eóganachta marginalized them both.[16]

Ptolemy's 2nd-century map of Ireland places a tribe he called the "Usdaie" roughly in the same area that the Osraige occupied.[17] The territory indicated by Ptolemy likely included the major late Iron Age hill-fort at Freestone Hill and a 1st-century Roman burial site at Stonyford, both in County Kilkenny.[18] Due to inland water access via the Nore, Barrow and Suir rivers, the Osraige may have experienced greater intercourse with Britain and the continent, and there appears to have been some heightened Roman trading activity in and around the region.[19] Such contact with the Roman world may have precipitated wider exposure and later conversion to Early Christianity.

From the fifth century, the name Dál Birn ("the people of Birn"; sometimes spelled dál mBirn) appears to have emerged as the name for the ruling lineage of Osraige, and this name remained in use through to the twelfth century. From this period, Osraige was originally within the sphere of the province of Leinster.

Déisi, Corcu Loígde usurpation and Christianization (c.450–625)

Several sources indicate that towards the end of the fifth century the Osraige ceded a swath of southern territory to the displaced and incoming Déisi sometime before 489.[20] The traditional accounts states that the landless, wandering Déisi tribe were seeking a home in Munster, through the marriage of their princess Ethne the Dread to Óengus mac Nad Froích, king of Munster. As part of her dowry, Ethne asked for the Osraige to be cleared off their land, but were repulsed several times by the Osraige in open battle before finally overcoming them through magic, trickery and guile.[21] The account mentions that at this defeat, the Ossorians fled like wild deer ("ossa" in Irish), a pun on their tribal name.

It appears that soon thereafter following this defeat, the hereditary Dál Birn kings were displaced for a period by the Corcu Loígde of south Munster. The Dál Birn remained in control of their northern territory while Corcu Loígde kings ruled the greater portion of southern Osraige around the fertile Nore valley until the latter part of the sixth century and the rise of Eóganachta dominating Munster. The new political configuration, probably the result of an Uí Néill-Eóganachta alliance against the Corcu Loígde,[22] caused a reduction in Osraige's relative status. In 582, Fergus Scandal mac Crimthainn, the king of Munster, was slain by Leinstermen and Osraige was therefore ceded from Leinster as blood-fine payment and attached the kingdom to the province of Munster.[23][24] Around that time (in either 581 or 583) the Ossorians (also referred to in the Fragmentary Annals as Clann Connla) had slain one of the last usurping Corcu Loígde kings Feradach Finn mac Duach and reclaimed most of their old patrimony.[25] The Dál Birn returned to full power by the first quarter of the seventh century.

Throughout this period, Ireland and Irish culture was thoroughly Christianized by the arrival of missionaries from the Britain and continent. Osraige appears to have seen a flourish of early Christian activity. Surviving hagiographic works, especially those relating to St. Ciaran of Saighir, attest that Osraige was the first Irish kingdom to receive a Christian episcopacy even before the arrival of St. Patrick; however, some modern scholars dispute this.[26] St. Patrick is believed to have traversed through Osraige, preaching and establishing Christianity there on his way to Munster. An early Irish church was founded in Osraige, perhaps in connection with St. Patrick's arrival in the territory, known as "Domhnach Mór" ("great church", located at what is now St. Patrick's graveyard in Kilkenny).[27][28] St. Cainnech of Aghaboe founded two churches in Osraige which later grew in importance: Aghaboe and Kilkenny, each of which successively held the episcopal see after Saighir. Additionally, a host of other early monastics and clerics laboured for the gospel in Osraige, making a lasting impact on the region which still exists down to the present.

Dál Birn Resurgence (c.625–795)

There is confusion among scholars as to the correct enumeration of the Corcu Loígde kings over Osraige, but by the reign of Scandlán Mór (d. 643 ca.) the Dál Birn dynasts regained control of their own territory, but not without intermittent dynastic competition.[29] The late seventh century witnessed an increase in hostilities between the men of Osraige and their neighbors to the south-east in Leinster, especially with the Uí Ceinnselaig. In the middle years of the eighth century, Anmchad mac Con Cherca was the most militarily active king in Munster, and was the first Ossorian king to gain island-wide notice by the chroniclers.[30] Upon his death in 761, Osraige witnessed civil war over the throne and Tóim Snáma mac Flainn, a scion from a different lineage emerged as king. Tóim Snáma was opposed by the sons of Cellach mac Fáelchair (died 735), and presumably Dúngal mac Cellaig (died 772). In 769, he was successful in battle versus them and they were put to flight.[31] In 770, he was slain, presumably by Dúngal his successor.[32]

During this time the churches of Osraige witnessed a flourish of growth and activity, with notable clerics from Osraige being recorded in the annals and at least one, St. Fergal, gaining international fame as an early astronomer and was ordained bishop of Salzburg in modern-day Austria. However, it is noteworthy that bishop Laidcnén son of Doinennach, abbot of Saighir was slain in 744.[33]

Osraige in the Viking Age (795–1014)

Because Osraige is bound by major rivers, this period witnessed the establishment of several significant Viking bases on and around the kingdom's borders in the ninth and early tenth centuries; with the Nore, Barrow and Suir watershed systems providing deep access into Osraige's interior.[19] Vikings came into conflict with the Irish on the River Suir as early as 812 and a large fleet sailed up the Barrow and Nore rivers, inflicting a devastating rout on the Osraige in 825.[34] A Norse longphort was planted by Rodolf son of Harald Klak at Dunrally between 850–62 on the border with the neighboring kingdom of Laois.[35] Other longphort settlements emerged at Woodstown[36] (c.830–860) and Waterford in 914. Consequently, Osraige endured much tumult and warfare but subsequently emerged politically dominant, becoming a major force in southern Ireland and even the one of the most militarily active kingdoms on the island by the middle of the ninth century. Originally granted semi-independent status within the province of Munster, the war-like and victorious rule of king Cerball mac Dúnlainge birthed a dramatic rise in Osraige's power and prestige, despite a heavy influx of Viking marauders to Ireland's shores.

Under the long reign of Cerball mac Dúnlainge between 843/4 to 888, Osraige was transformed from a relatively unimportant kingdom into one of Ireland's most powerful overlordships, which surpassed that of both Munster and Leinster and even threatened Uí Néill hegemony over southern Ireland.[37] There is circumstantial evidence which indicates that early in his reign, Cerball may have even sent emissaries to establish international diplomacy with the Carolingian Empire's western-third under Charles the Bald who was also dealing with Viking threats.[38] He established dual marriage alliances with the High King Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid and successfully forced Máel Gualae, king of Munster to recognize Osraige's formal independence from Munster in 859.[39][40] The later Icelandic Landnámabók uniquely names Cerball as king of Dublin and the Orkney islands during his reign, yet scholars regard this as an interpolation borrowed from the influential narrative found in the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, likely composed by Cerball's eleventh century descendant Donnchad mac Gilla Pátraic.[41]

Cerball's descendant king Gilla Pátraic mac Donnchada (r. 976–996) proved an able ruler, and by the late 10th century the hereditary ruling descendants of Osraige had adopted the surname Mac Giolla Phádraig as their patronymic. By the late tenth century, Osraige was brought into conflict with the ambitious Dalcassian king Brian Boruma, who gained supremacy over all Ireland before being killed in the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, in which the Ossorians did not partake. The Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib relates a story that victorious but wounded Dalcassian troops were challenged to battle by the Ossorians as they were returning home through Osraige after the battle of Clontarf, but some authors doubt the validity of this story, as the source is widely considered a later Dalcassian propaganda.[42][43]

Osraige during the First Irish Revival (c. 1015 – 1165)

During the period after the decline of Viking threats, many of Ireland's smaller kingdoms became dominated by larger ones, in a natural yet bloody evolution towards centralized monarchy. Various families contended for the high-kingship. Allegiance with Osraige could make or break a king's bid for the high-kingship, although the kings of Osraige never attempted the position themselves. King Donnchadh mac Gilla Pátraic, arguably Osraige's most powerful ruler who brought the kingdom to the zenith of its power, plundered Dublin, Meath and successfully conquered neighboring Leinster in 1033, held the Óenach Carmán and ruled both kingdoms until his death in 1039. In 1085 and 1114, the city of Cill Chainnigh was burned.[44][45]

Additionally, major changes to the structure and practices of the Irish Church, brought it away from its historic orthodox practices and more in line with the massive Gregorian Reform movement which was already taking place on the continent. Significantly, the Synod of Rath Breasail was part of this movement, likely held in the northernmost territory of Osraige in 1111.[46]

By the early-12th century, fighting had erupted within the dynasty and split the kingdom into three territories. In 1103, Gilla Pátraic Ruadh, king of Osraige and many of the Ossorian royal family were killed on campaign in the north of Ireland.[47] Two new claimants to the throne then emerged, both scions of the Mac Giolla Phádraig clan. Domnall Ruadh Mac Gilla Pátraic was the king of greater Osraige, often called Tuaisceart Osraige ("North Osraige") or Leath Osraige ("Half-Osraige"); and Cearbhall mac Domnall mac Gilla Pátraic in Desceart Osraige ("South Osraige"), a smaller portion of the southernmost part of Osraige bordering Waterford. Additionally, the Ua Caellaighe clan of Mag Lacha and Ua Foircheallain in the extreme north Osraige declared their independence from Mac Giolla Phádraig rule under Fionn Ua Caellaighe. Thus the north and south fringes of the kingdom broke apart from the centre, each with subsequent competing dynasts until the arrival of the Normans.[48] While the north and south extremities of the kingdom were broken away, the majority of central Osraige around the fertile Nore valley maintained greater stability, and is most often referred to simply as "Osraige" in most annals for the period.

Despite its fracturing, Osraige was still powerful enough to oppose and inflict defeats upon Leinster.[49] As retribution in 1156-7, the high king Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn led a massive campaign of destruction deep into Osraige, laying waste to it from end to end, and officially subjected it to Leinster.[50][51]

Decline during the Norman Invasion (1165–1194)

Much of the background drama and initial action of the Norman advance played out on the battlefields and highways of Osraige. The kingdoms of Osraige and Leinster had also witnessed increased mutual hostility prior to the Normans. Significantly, Diarmaid Mac Murchadha, the man who would one day become king of Leinster and invite the Normans into Ireland, was himself fostered as a youth in north Osraige, in the territory of the Ua Caellaighes of Dairmag Ua nDuach who sought to undermine their Mac Giolla Phádraig overlords. In the 1150s, high king Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn made a devastating punitive campaign on the divided Osraige, burning and pillaging the whole kingdom and subjected it to Leinster overlordship. Thus, Diarmaid Mac Murchadha came to intervene several times into the disputes of Ossorian succession. After Mac Murchadha's exile and return in 1167, tension was heightened between Osraige and Leinster by the blinding of Mac Murchadha's son and heir, Éanna mac Diarmat by the prince of greater Osraige, king Donnchad Mac Giolla Phádraig.[52] Mac Murchadha's initial mercenary force under Robert FitzStephen landed close to the border of Osraige at Bannow, took Wexford and immediately turned west to invade Osraige, acquiring hostages as a nominal token of submission.[53] Later still, another auxiliary force under Raymond FitzGerald (le Gros) landed just opposite Osraige's border at Waterford, and won a skirmish with its inhabitants.[54] By 1169, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (Strongbow) had also landed with a major force outside of Waterford, married Mac Murchadha's daughter Aoife and sacked the city.[55] Later that year, a major conflict was fought in the woods of Osraige near Freshford when Mac Murchadha and his Norman allies under Robert FitzStephen, Meiler FitzHenry, Maurice de Prendergast, Miles FitzDavid, and Hervey de Clare (Montmaurice) defeated a numerically superior force under Domnall Mac Giolla Phádraig, king of greater-Osraige, at the pass of Achadh Úr following a feigned retreat in a three-day battle.[56][57] Shortly thereafter de Prendergast and his contingent of Flemish soldiers defected from Mac Murchada's camp and joined king Domnall's forces in Osraige before quitting Ireland for a time.[58] In 1170, MacMurchada died, leaving Strongbow as the de facto king of Leinster, which in his understanding, included Osraige. At Threecastles, Strongbow and Mac Giolla Phádraig agreed to the Treaty of Odogh (Ui Duach) in 1170, in which de Prendergast saved the life of the prince of Osraige from a treacherous assassination.[59] Osraige was afterwards invaded by Strongbow's troops and an Ua Briain force from Thommond. In 1171, King Henry II of England landed in nearby Waterford Harbour with one of the largest injections of English military strength into Ireland. On the banks of the Suir, Henry secured the submission of many of the kings and chiefs of southern Ireland; including Tuaisceart Osraige's king, Domnall Mac Giolla Phádraig.[60] In 1172, the Norman adventurer Adam de Hereford was granted land by Strongbow in Aghaboe, north Osraige.[61] After Henry was recalled from Ireland to deal with the aftermath of Thomas Becket's murder and the Revolt of 1173–74, Osraige continued to be a theater of conflict. Raymond FitzGerald plundered Offaly and traveled through Osraige to win a naval engagement at Waterford. Later, a force from Dublin inflicted a defeat on Hervey de Clare in Osraige. In 1175, the prince of Osraige assisted a force under Raymond FitzGerald to relieve the city of Limerick which had been besieged by the forces of Domnall Mór Ua Briain. Later, Cambrensis relates a defeat of the men of Kilkenny and their prince by a Norman force from Meath. The noted adventurer Robert le Poer won lands in Osraige, but was later killed there against the natives. In 1185, Prince John, then Lord of Ireland and future King of England, traveled from England to Ireland to consolidate the Anglo-Norman colonisation of Ireland, landing at Waterford near the border of Osraige. He secured the allegiance of the Irish princes and traveled through Osraige to Dublin, ordering several castles to be constructed in the region. The last recorded king of central Osraige was Maelseachaill Mac Gilla Patráic, who died in either 1193 or 1194.[62][63] However, the kingdom and a continuous succession of rulers remained intact in the north, subsequently called "Upper Ossory" into the mid-sixteenth century.

Upper Ossory and Kilkenny (1192–1541)

After the initial Norman Invasion of Ireland, the famous and formidable William Marshal arrived in Osraige by 1192 and acquired claims to the land through his marriage to Isabel de Clare, daughter of Strongbow and Aoife Mac Murchada, daughter of Diarmait Mac Murchada. Marshal began stone construction on the large fortification at Kilkenny Castle which was completed by 1195 and was largely responsible for forcing the Mac Giolla Phádraigs from their southern power base around the River Nore; their ancient rights revoked and a decree of expulsion pronounced on the entire clan.[64] The northern districts of Mag Lacha and Ui Foircheallain (henceforth called Upper Ossory which had formerly broken away from Osraige under Ua Caellaighe/Ua Faeláin and Ua Dubhsláine rule since 1103, and which had subsequently seen English settlement from the Normans, thus became targeted by the expelled Mac Giolla Phádraigs and their Ossorian followers for resettlement.[65] This caused a land war in Upper Ossory between those clans already residing there, the new English settlers, and the incoming clans from south and central Osraige driven out by Earl Marshal, which lasted more than a century and a half before the Mac Giolla Phádraigs established full supremacy over the region. Subsequently, the chaos of this poorly recorded conflict caused the then bishop of Ossory, Felix O'Dulaney, to permanently remove the episcopal see from Aghaboe and initiate construction of the cathedral in Kilkenny. Upper Ossory thus remained an independent Gaelic lordship until the mid-sixteenth century, with its Mac Giolla Phádraig rulers retaining claims to the kingship of all Osraige and being recorded as such, or sometimes "King of the Slieve Blooms".[66] The majority of Osriage was divided up and partitioned amongst various Norman adventurers, especially those within the household of William Marshal who arrived to take charge of lands which were claimed by his wife's inheritance.[67] Likely arriving under Marshal was Sir Thomas FitzAnthony who was granted extensive lands in lower Ossory and elsewhere (Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny is named after him) and was an important and successful administrator for the Crown; being made seneschal of all Leinster from 1215 to at least 1223.[68][69] Upper Ossory was formally incorporated into the Henry VIII's Lordship of Ireland by the submission of Barnaby Fitzpatrick, 1st Baron Upper Ossory under the policy of surrender and regrant in 1537. This ironically had the effect of preserving Gaelic culture in Upper Ossory long into the future, since the Crown no longer dealt harshly with the territory.[70] In 1541, The Mac Giolla Phádraig was ennobled as Baron Upper Ossory. Other members of the family were later created Earl of Upper Ossory and Baron Castletown, the last of whom, Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown, died in 1927. Because they clung to the last fragments of the kingdom, that Ossorian lineage is marked as one of the oldest known or most continuously settled dynasties in Western Europe.

By the late fourteenth century, members of the Butler dynasty purchased or inherited most of southern Osraige, purchased Kilkenny Castle and administered it from there as part of the Earldom of Ormond (and later Earldom of Ossory), from which County Kilkenny was shired. During this period, Kilkenny ranked very close behind Dublin as the main seat of English power in Ireland, with Parliament meeting there as early as 1293 and recurring many times until 1536.[71] The Bruce Invasion of Ireland saw Edward Bruce temporarily seize Gowran, once a seat of the kings of Osraige. By 1352, the unified formation of modern County Kilkenny had taken shape. In 1367, the Statutes of Kilkenny were enacted attempting to quell intermarriage and commerce between the English and Irish, but to little effect.

Ossorian clans

In The Book of Rights, the Osraige are labeled as Síl mBresail Bric ("the seed of Bresail Bric") after Bressail Bricc, a remote ancestor of the Ossorians.[72] Bressail Bricc had two sons; Lughaidh, ancestor of the Laigan, and Connla, from whom the Ossorians sprang, through Óengus Osrithe.[73][74] Thus, the people of Osraige were also sometimes collectively referred to as Clann Connla.[75] Over time as lineages multiplied, surnames were eventually adopted. The following clans were the native land-holders before the arrival of the Normans:[76]

- Mac Giolla Phádraig (Fitzpatrick, Gilpatrick, McIllpatrick, MacSeartha) hereditary Dál Birn kings of Osraige through king Cerball's son Cellach

- Ua Dubhsláine (O'Delany) of Coill Uachtarach (Upper Woods)

- Ua hÚrachán (O'Horahan) of Uí Fairchelláin (Offerlane)

- Ua Bruaideadha (O'Brody, Brooder, Brother, Broderick) of Ráth Tamhnaige

- Ua Caellaighe (O'Kealy, O'Kelly) of Dairmag Ua nDuach (Durrow-in-Ossory), who as asserted by Carrigan, changed their name to Ua Faeláin (O'Phelan, Whelan) below

- Ua Faeláin (O'Phelan, Whelan) of Magh Lacha (Clarmallagh) (formerly Ua Caellaighe, above)

- Ua Bróithe (O'Brophy) of Mag Sédna

- Ua Caibhdheanaigh (O'Coveney, Keveny) of Mag Airbh

- Ua Glóiairn (O'Gloherny, Glory, O'Gloran, Cloran, Glorney) of Callann

- Ua Donnachadha (Dunphy, O'Donochowe, O'Dunaghy, O'Donoghue, Donohoe, Donagh) of Mag Máil

- Ua Cearbhaill (O'Carroll, O'Carrowill, MacCarroll) of Mag Cearbhail

- Ua Braonáin (O'Brennan) of Uí Duach (Idough)

- Ua Caollaidhe (O'Kealy, O'Coely, Quealy) of Uí Bercháin (Ibercon)

- Mac Braoin (MacBreen, Breen) of Na Clanna

- Ua Bruadair (O'Broder, Broderick) of Uí nEirc (Iverk)

- Ua nDeaghaidh (O'Dea) of Uí Dheaghaidh (Ida)

Notable nobility

| Dál Birn / Mac Giolla Phádraig | |

|---|---|

| Parent house | Ulaid / Érainn |

| Country | Ireland |

| Titles |

Kingdom of Ireland titles: |

An important Ossorian genealogy for Domnall mac Donnchada mac Gilla Patric is preserved in the Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson B 502, tracing the medieval Mac Giolla Phádraig dynasty back to Óengus Osrithe, who supposedly flourished in the first or second century.[78][79]

- Óengus Osrithe the first recorded king and namesake of the kingdom is the semi-legendary Óengus Osrithe, who lived in either the first or second century.

- Loegaire Birn Buadach gave his early epithet to the ruling lineage amongst the Ossorian people, the "Dál Birn" (lit. "the portion of Birn").

- Cerball mac Dúnlainge (King of Osraige from 846 to 888;[80] King of Dublin from 872 to 887;[81][82] Earl of Orkney prior to 888[81])

A celebrated king of Osraige (and likely Osraige's most famous monarch) was Cerball mac Dúnlainge, who ruled Osraige vigorously from c. 846 to his death in 888 and was the direct male progenitor of the later medieval Mac Giolla Phádraig dynasts. The Icelandic Landnámabók describes Cerball (Kjarvalur) as ruler of Dublin and Earl of Orkney and opens with a list of the most prominent rulers in Viking-age Europe, listing this Ossorian king alongside Popes Adrian II and John VIII; Byzantine Emperors Leo VI the Wise and his son Alexander; Harald Fairhair, king of Norway; Eric Anundsson and his son Björn Eriksson rulers of Sweden; Gorm the Old, king of Denmark; and Alfred the Great, king of England.[83] Cerball features prominently in the annals and other historical texts, especially in The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland as an archetype of a Christian king who consistently vanquishes his enemies, especially pagan Vikings. In this chronicle, Cerball is recorded allying with rival bands of Vikings to defeat them during his early career as king. He was also close enough to the Norse–Gaels that he features under the name "Kjarvalr Írakonungr" in several medieval Icelandic pedigrees through his daughters. Cerball was likely the most powerful king of his day in Ireland, even plundering the lands of his brother-in-law the high king, which resulted in the kingdom of Osraige being officially dis-joined from the province of Munster. During his lifetime he is recorded to have even ruled over Dublin (from 872 to 888) and as far as the Orkneys due to his interconnections with his Viking neighbors.

- Land ingen Dúngaile (Princess of Osraige; daughter of king Dúngal mac Cellaig)

Princess Land (sometimes spelled Lann) was a noteworthy figure in Irish politics during a critical time in Osraige's history, witnessing its dramatic rise to power under the rule of her brother Cerball mac Dúnlainge, in which she had a hand. She was married to the famous High King of all Ireland, Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid (who reigned from 846 to 862) and gave birth to his formidable son Flann Sinna who was also High King from 879 to 916. (She is thus also the grandmother of High King Donnchadh Donn mac Flainn.)

- Gilla Pátraic mac Donnchada (King of Ossory from 976 to 996)

King Cearbhall's descendant, Gilla Pátraic mac Donnchada, was king of Osraige from 976 to 996, and was the source of the patronymic Mac Giolla Phádraig. His wife was Máel Muire ingen Arailt, likely an Uí Ímair bride. He was an implacable opponent of Brian Boruma in his expansion over southern Ireland, being captured by him in 983 and released the following year.[84] Later in his reign, he devastated Mide, and was killed in battle against Donnduban mac Imair, prince of Limerick, and Domnall mac Fáelán, king of Déisi.

- Donnchad mac Gilla Pátraic (King of Osraige from 1003 to 1039; king of Leinster from 1033 to 1039)

In 1003, he killed his cousin, King Cellach. In 1016, he killed Donn Cuan mac Dúnlaing, king of Leinster, and Tadc ua Riain, king of Uí Drona.[85] In 1022, he killed Sitriuc mac Ímair, king of Port Lairge (Waterford).[86] In 1026, Donnchad spent Easter with the coarb of Patrick and Donnchad mac Briain.[87] In 1027, he blinded his relative Tadc mac Gilla Pátraic.[88] In 1033, Donnchad also took the kingship of Leinster and held the Fair of Carman to celebrate his over-kingship.[89] In 1039, he led a hosting as far as Knowth and Drogeda.,[90] and he died the same year.[91] Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles, through his daughter Mael Muire, appears to have been the maternal grandfather of Donnchad mac Gilla Pátraic, the Osraige king of Leinster. Thus the Mac Giolla Phádraigs or Fitzpatricks of Ossory are probably matrilineal descendants of the Uí Ímair. King Cerball was an ally of their (probable) founder Ívar the Boneless, the Viking king of Waterford. It is also possible that Donnchad's father, Gilla Pátraic mac Donnchada, was somehow a relation of Ívar the Boneless, who had a son named Gilla Pátraic.

- Derbforgaill ingen Tadhg Mac Giolla Pádraig (Princess of Osraige, died 1098)

Derbforgaill, daughter of Tadhg Mac Giolla Pádraig was married to Toirdelbach Ua Briain, king of Munster and de facto high king of Ireland. From him, she bore two sons: Tadhg and Muirchertach Ua Briain, who also later became high king. She reposed in 1098 in Glendalough.[92]

Saints with Ossory connections

The monastic settlements of Saighir, Aghaboe and Kilkenny were planted by Christian saints. The activity of Christian religious leaders under the patronage of the kings did much to increase the learning, literacy and culture within the kingdom.[93] According to his vitae, Saint Patrick traversed Osraige on his route to Munster, preaching, converting, founding churches and leaving behind holy relics and a disciple named Martin.[94][95] A number of other saints had connections to Ossory, working both within Ireland and abroad in Britain and Europe:

- St. Ciarán of Saighir "The Elder", himself a scion of the Ossorian ruling Dál Birn lineage is reputed to have evangelized the kingdom before the arrival of St Patrick who also preached there.[96] He founded the church of Saighir from which he evangelized the kingdom. It eventually became the episcopal see of Ossory, and the burial place of its Christian kings. St Ciarán was succeeded by his disciple, St Carthage the Elder. St Ciarán's feastday is 5 March, along with St. Carthage and St. Piran. St. Kieran's College in Kilkenny (Ireland's oldest Roman Catholic secondary school) is named after him.[97] (In Cornwall St. Ciarán is identified as one and the same person with Saint Piran, the patron saint of tin miners and all Cornwall.)[98][99] A relief statue of St. Ciarán stands in a high niche atop the Chapter House at St. Mary's in Kilkenny.[100]

- St. Carthage the Elder, a son or grandson of Óengus mac Nad Froích and St. Ciarán's successor at Saighir. His feastday is also celebrated with St. Ciarán on 5 March.

- St. Cainnech of Aghaboe established two monastic centers in Ossory in the 6th century, at Aghaboe and Kilkenny, now named after him. His feast is 11 October.

- St. Modomnoc of Ossory traveled there from Wales as a disciple of St. David, and is reputed to have brought Ireland's first colonies of domesticated honeybees.[101] His feast is 13 February.[102]

In a little boat, from the east, over the pure-colored sea, my Domnoc brought the gifted race of Ireland's bees. ~ Félire Óengusso[103]

- St. Scuithin, also bearing Welsh connections via St. David, worked his asceticism in south Ossory, in what is now Castlewarren and Freynestown.

- St. Nem Moccu Birn, successor to St. Enda of Aran is recorded as having been also of the Dál Birn of Ossory and a kinsmen of St. Ciarán of Saighir.[104] His feast is 14 June.

- St. Broccán Clóen of Rossturic, was the author of a famous poem in praise of St. Brigid of Kildare (found in the Liber Hymnorum[105] and is mentioned in the Félire Óengusso under September 17.[106]

- Mo Lua of Killaloe who founded the monasteries of Killaloe and Clonfert-Mulloe[107][108] (now Kyle in County Laois) in northern Osraige.[109] According to the Martyrology of Donegal St. Molua mac Carthach (also known as St. Lua, or Da Lua) was trained under St. Comgall of Bangor Abbey. His father was Carthach mac Dagri, while his mother was Sochle of the Dál Birn, the ruling tribe of Osraige.[110][111] William Carrigan speculated his birth around the year 540 AD, and the Annals of the Four Masters records his death in 605 AD. His feast is 4 August.

- St. Gobhan, who was also known for his founding an abbacy of the monastery of Oldleighlin, was also active at a later date in Ossory at Killamery. It would appear that sometime before 633 AD he left his monastery at Oldleighlin, and along with numerous monks journeyed west into the kingdom of Ossory and settled at Killamery. Whether he founded Killamery or merely enhanced it, is disputed; however during his abbacy its fame and importance flourished. The 9th-century book Félire Óengusso, (The Feastology of Oengus), states about him: "of Gobban of Cell Lamraide in Hui Cathrenn in the west of Ossory, a thousand monks it had, as experts say and of them was Gobban."[104]

- St. Findech of Cell Fhinnche, (Killinny, Kilkenny) described in the Félire Óengusso as a martyr, though this likely refers to ascetic exile. His feast is February 2.[112]

- St. Muicin, bishop and confessor, whose feast is celebrated on 4 March. His name appears under the Irish forms Muicin, Muccin, Mucinne, and, in Latin, as Moginus and Mochinus. According to his pedigree in the Book of Leinster, he was of the royal race of Ossory, the Dal Birn ; thus: "Muccin, son of Mocha, son of Barind, son of Findchadli, son of Dega, son of Droida, son of Buan, son of Loegaire birn buadhach, son of Aengus Osrithe. Decnait, daughter of Gabrin, [and] sister of Fintan of Cluain-Eidhnech, was Muccin's mother." He was venerated as patron of Mayne, Kylermugh, Kilderry and Sheepstown. He lived in the same period as his uncle, St. Fintan the great founder of Clonenagh, and died in the year 630. He is also commemorated in the Martyrology of Tallaght.

- St. Fergal was an abbot of Aghaboe in the 8th century and later traveled to Franconia where he was well received by Pippin the Younger. By invitation of Odilo, Duke of Bavaria, he arrived at Salzburg and was eventually made bishop there, being known ever after as St. Vergilius of Salzburg the geometer. His feast is November 27.

![]() Media related to Virgilius of Salzburg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Virgilius of Salzburg at Wikimedia Commons

- Perhaps most famously, Óengus of Tallaght, the compiler of the first calendar of Irish saints, (called the Félire Óengusso) was born and raised in northern Ossory at Clúain Édnech (Clonenagh, Co. Laois), and began his monastic vocation there as his calendar states.[113] His feast is March 11.

- The relics of Saint Nicholas are also reputed to have been stolen from Bari by crusading knights, and buried in the south of Osraige near Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny; a stone slab marks this site. This would date from the period immediately following the disestablishment of southern Osraige as a kingdom, while the northern third still remained.

- St. Patrick reputedly passed through Osraige according tradition,[114] and St. Ciarán's vitae relate St. Patrick ordained a man for the Osraige named Martin.[115] A freestanding statue of him erected in honor of the bishop of Ossory stands in Kilkenny, in addition to other local commemorations.[100] The Mac Giolla Phádraig rulers of Osraige adopted their surname in honour of St. Patrick from their 10th-century ancestor, king Giolla Phádraig, and appear to be one of the few Irish dynasties to bear a name of saintly derivation. (Another example includes the Ua Mael Sechlainn (O Melaghlin) dynasts who were kings of Mide.)

Historic sites

Modern Counties Laois and Kilkenny preserves many of the ancient and medieval site associated with the kingdom of Osraige.[117] A long and well-attested sculptural tradition of stone carving, especially the creation of Irish high crosses developed under the Dál Birn / Mac Giolla Phádraig kings of Osraige.[93][118] Nearly all of Ireland's earliest stone high crosses are found within the ancient kingdom of Osraige or close to its borders.[119] Great examples of this tradition include the fine crosses still preserved at Kinitty, Ahenny and Killamery, amongst other sites. Some historians have asserted that a pre-Norman fortification existed at the site upon which Kilkenny Castle is built; likely the ancient capital of the kingdom. St. Ciarán is said to have founded the influential monastery of Seirkieran, in present-day Clareen.[120] Saighir was the first episcopal seat within the kingdom and was the burial site of the Kings of Osraige. There, the ruins of a monastic site, earthworks, a holy well, the ruined base of an Irish round tower, a medieval defensive motte, numerous early Christian cross-slabs, bases and gravestones can be found, next to a 19th-century Church of Ireland parish.[121][122][120][123] St. Canice founded two important churches in the kingdom, at Aghaboe and Kilkenny, each in turn becoming the capital of the diocese after Saighir. Aghaboe Abbey served as Osraige's second ecclesiastical seat, before it was again later relocated to Kilkenny some time in the twelfth century. St Canice's Cathedral in Kilkenny city exhibits well-preserved ninth-century round tower which can be climbed to the top.[124] In April 2004, a geophysical survey using ground-penetrating radar discovered what were likely the original foundations of the twelfth century cathedral of the diocese of Ossory and another very large structure which was possibly a royal Mac Giolla Phádraig palace; noting that the site bears a strong resemblance to contemporaneous structures at the Rock of Cashel.[125] Jerpoint Abbey, was founded near present-day Thomastown in 1160 by king Domnall Mac Goilla Phádraig.[126] There is some debate as to whether Jerpoint was either Benedictine or Cistercian during its first twenty years, however by 1180, king Domnall Mac Goilla Phádraig brought Cistercian monks from nearby Baltinglass Abbey and it remained such thereafter.[126][127] A well-preserved 30-meter, capless round tower can be seen at Grangefertagh. In 1999, a hoard of 43 silver and bronze items dated to 970 AD was discovered in a rocky cleft deep in Dunmore Cave, containing silver ingots and conical buttons woven from fine silver.[128] The cave was the site of a recorded Viking massacre in 928.[129]

In 1984, a series of commemorative cast stone panels sculpted by Joan Smith were installed as a facade on the buttress walls of Ossory Bridge which forms part of the Ring Road over the River Nore connecting the N10 from Carlow to Waterford.[130] The facade symbolically depicts the history of the south Kilkenny area from the time of the mythological figure of Oengus Osrithe to the late twentieth century.[131]

-

St. Canice's Cathedral, with ninth-century round tower. Only the tower dates from the pre-Norman period

-

Ninth-century round tower at Grange Fertagh

-

Window of Aghaboe Abbey

-

Saighir round tower and priory wall

-

Ahenny high cross, North

-

Ahenny high cross

-

Graiguenamanach high cross, East

-

Jerpoint Abbey, founded in 1160 by Domnall Mac Goilla Phádraig

-

Dunmore Cave ("Dearc Fearna"), Ballyfoyle, Co. Kilkenny

Overlap with the Diocese of Ossory

The Diocese of Ossory was first established in the fifth century with the mission of St. Ciarán of Saighir, the borders of which were permanently set at the Synod of Ráth Breasail om 1111 AD. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Ossory still to this day provides a very close outline of the kingdom's borders.[133] In the earliest times, the chief church in Osraige was undoubtedly Seir Kieran (County Offaly), the chief church of St Ciarán, but at some time in history it had been eclipsed by Aghaboe (County Laois), chief church of Saint Cainnech, and later moved to Kilkenny, which was also founded by the same saint. The record of the Irish annals also points to Freshford, County Kilkenny being of some importance, while archaeological evidence suggests that Kilkieran, Killamery and Kilree (all County Kilkenny) and Domnach Mór Roigni (now Donaghmore, County Laois) were also significant early ecclesiastical sites.[134] Ossory is the only region in Ireland known to have two patron saints; St. Ciarán of Saighir and St. Cainnech of Aghaboe.[135] Due largely to the scholarly work of canon William Carrigan in researching and compiling his four volume opus The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory, the history of the kingdom and its peoples is one of the most complete of any in Ireland. Furthermore, the Database of the Monasticon Hibernicum Project launched by Ailbhe Mac Shamhráin lists all known historic monastic foundations associated with diocese of Osraige.[136]

In literature and culture

Annals, sagas and historical sources

The politics and history of the kingdom are well-attested to in the various Irish Annals in which Osraige is often presented as a major kingdom. The Osraige appear as the final opponents of their southern neighbours the Déisi in the cycle The Expulsion of the Déisi.[137][21] While portrayed as unconquerable in battle, the Osraige are eventually overcome by the Déisi in the end by magic and treachery and thus cede to them the southern territory between the River Suir and the sea which the Déisi ever-after occupied. Strongly associated with the eleventh-century rule of Donnchad Mac Giolla Phádraig (who reigned as king over Leinster until his death in 1039 AD) are the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland which are famous for their heroic portrayal of the ninth-century Ossorian king Cerball mac Dúnlainge in his many victorious struggles against pagan Vikings in Ireland.[138] The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland were believed to be commissioned by Donnchad Mac Giolla Phádraig as historical propaganda for Osraige's eleventh-century rise to power, and likely influenced the creation of other later pseudo-chronicles such as Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib.[139] Within the Fragmentary Annals, editor and translator Joan Radner has detected a strong focus on Ossorian tradition, especially relating to king Cerbhall mac Dunglange, suggesting the hypothetical Osraige Chronicle as a possible source.[139]

The men from two fleets of Norsemen came into Cerball son of Dúnlang's territory for plunder. When messengers came to tell that to Cerball, he was drunk. The noblemen of Osraige were saying to him kindly and calmly, to strengthen him: ‘What the Norwegians are doing now, that is, destroying the whole country, is no reason for a man in Osraige to be drunk. But may God protect you all the same, and may you win victory and triumph over your enemies as you often have done, and as you still shall. Shake off your drunkenness now, for drunkenness is the enemy of valor.’

When Cerball heard that, his drunkenness left him and he seized his arms. A third of the night had passed at that time. This is how Cerball came out of his chamber: with a huge royal candle before him, and the light of that candle shone far in every direction. Great terror seized the Norwegians, and they fled to the nearby mountains and to the woods. Those who stayed behind out of valor, moreover, were all killed.

When daybreak came the next morning, Cerball attacked all of them with his troops, and he did not give up after they had been slaughtered until they had been routed, and they had scattered in all directions. Cerball himself fought hard in this battle, and the amount he had drunk the night before hampered him greatly, and he vomited much, and that gave him immense strength; and he urged his people loudly and harshly against the Norwegians, and more than half of the army was killed there, and those who escaped fled to their ships. This defeat took place at Achad mic Erclaige. Cerball turned back afterwards with triumph and great spoils.

The early twelfth-century Irish epic Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib portrays the Dalcassian struggle against Osraige and its brief subjugation by Brian Boru. It records some early Viking activity in and around Osraige[141] and ends with the embarrassing account of the Ossorians seeking to attack the victorious and wounded Dalcassian troops returning after the Battle of Clontarf. The Ossorians are recorded as intimidated when they see the wounded Dalcassian troops tying themselves upright to stakes, and withdraw from outright combat, giving harassing pursuit instead.[141] Ironically, Radner suggests this chronicle may have been influenced by the earlier eleventh century Osraige Chronicle which lionized king Ceabhall mac Dúnlainge and survives with the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland.[139]

The kingdom is mentioned in countless surviving poems, songs and other medieval Irish texts. Lebor na gCeart ("The Book of Rights") aims to list the stipends paid to and by the kings of Osraige. The work Cóir Anmann ("The Fitness of Names") claims to give the etymology of the name Osraige, along with one its kings, Cú Cherca mac Fáeláin.[12] The kingdom of Osraige with some of its noteworthy characteristics and clans gains some mention in the Dindsenchas (literally "place-lore"), a composite collection of prose and metrical verse which aided in the rote memory of the topography and place-named of Ireland- some of it preserving Irish pre-literary oral tradition. Regarding Osraige, the names of its topographic features and roads are explained, as well as a reference to horse fighting.[142][143] The twelfth-century Banshenchas (literally "women-lore") composed by Gilla Mo Dutu Úa Caiside of Ard Brecáin, recites a number of key Ossorian kings and queens, and others who descend from them.[144] Additionally, Osraige is mentioned in a poem attributed to king Aldfrith of Northumbria during his exile in Ireland, describing the various things he saw there about the year 685.[145] Certain nobility of Osraige are mentioned in The Prophecy of Berchán, which hints ambiguously at the possibility of Ossorian inter-marriage with the Scottish kings.

I found from Ara to Gle, in the rich country of Ossory, sweet fruit, strict jurisdiction, men of truth, chess-playing.

King Aldfrith of Northumbria, Ro dheat an inis Finn Faíl.[146]

The kingdom is sometimes personified in the character of Mícheál Dubh Mac Giolla Ciaráin, a fictional prince of Osraige in several modern poems including Ossorie, A Song of Leinster by Rev. James B. Dollard[147] and especially Welcome to the Prince, an eighteenth-century Jacobite poem written in Irish by William Heffernan "Dall" ("the Blind"), and translated into English by James Clarence Mangan.[148][149][150]

Nordic literary history records several members of the Ossorian ruling lineage in the sagas. King Cerball mac Dúnlainge himself is listed as "Kjarval, king of the Irish" (Kjarvals Írakonungs) in the Icelandic genealogies recorded within Njal's Saga, and through his daughters is reckoned as an ancestor of several important Icelandic families.[151] His reign is directly referenced in the Icelandic Landnámabók where he is listed as one of the principle rulers of Europe. His daughter, Eithne, appears as a type of sorceress in the Orkneyinga saga, as the mother of Earl Sigurd the Stout and the creator of the famed raven banner.[152][153][154] This would make Earl Sigurd of the Orkneys a possessor of Ossorian maternal lineage. Sigurd also appears briefly in St Olaf's Saga as incorporated into the Heimskringla and in the Eyrbyggja Saga. There are various tales about his exploits in the more fanciful Njal's Saga as well as the Saga of Gunnlaugr Serpent-Tongue, Thorstein Sidu-Hallsson's Saga, the Vatnsdæla Saga and in the tale of Helgi and Wolf in the Flateyjarbók.[155][156] He also appears in the Irish propagandistic work Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib as an opponent of Brian Boruma at the Battle of Clontarf, and his death there is recorded in the Annals of Ulster.

The kingdom of Ossory also features prominently in twelfth-century Norman literature. Two works by Gerald of Wales on Ireland, Topographia Hibernica[157] and Expugnatio Hibernica[158] pay special attention to some kings of Ossory, its geography and the Norman battles fought therein. Gerald Cambrensis also writes about a fabulous tale involving the werewolves of Ossory. This legend was repeated in Fynes Moryson's 17th-century writing, Description of Ireland[159] and in a much later book, The Wonders of Ireland, by P. W. Joyce, published in 1911.[160] In addition, Ossory features prominently as a setting for scenes in the Norman-French lay The Song of Dermot and the Earl.[161]

The name of the kingdom survives in The Red Book of Ossory; a fourteenth-century register of the Roman Catholic diocese of Ossory, and which is associated with Richard Ledred[162] who was bishop of Ossory, from 1317 to 1360.[163] The book contains copies of documents which would have been important for the administration of the diocese: constitutions, taxations, memoranda relating to rights and privileges, deeds and royal letters, as well as the texts of songs composed by Bishop Ledred.[164] The book now resides at the Church of Ireland RCB Library in Dublin, and has been digitized.[164] Geoffrey Keating also records much information and tradition about Ossory in his major work, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (literally "Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland", more usually translated "History of Ireland").[165][166] After Cogadh Gáedel re Gallaib, his work is a secondary source for Ossory's opposition to the victorious Dalcassian forces returning from the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, as well as the only known source for information about the important Synod of Ráth Breasail which may have occurred on the northern borders of Ossory, near present-day Mountrath in 1111. The kingdom of Ossory and some of its primary saints are mentioned by the Welsh clergyman Meredith Hanmer in his Chronicle of Ireland, which was posthumously published by Sir James Ware in 1633.[167][168][169] Hanmer himself was briefly active in the Diocese of Ossory in 1598. In 1905, William Carrigan published his authoritative history of the kingdom in The History And Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory in four volumes.

Namesakes

The name of the former kingdom survives in the present-day town names of Borris-in-Ossory and Durrow-in-Ossory, as well as in the now defunct Ossory UK Parliament constituency. The name also survives in the title of the annual Ossory Agricultural Show, a livestock, produce and crafts competition founded in 1898 and patronized by Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown, and now held in western Coolfin County Laois.[170] The famous artist Ronald Ossory Dunlop bore the kingdom's name personally, perhaps in part because his mother's maiden name was Fitzpatrick. Three ships of the British Royal Navy bore the name HMS Ossory. A thoroughbred racehorse named Ossory (1885–1889) was owned by the 1st Duke of Westminster. Several Irish-speaking schools in Kilkenny also use the name Osraí including Gaelscoil Osraí[171] and Coláiste Pobail Osraí.[172] A black metal band from the US has adopted the name Osraige.[173][174] Ossory Bridge, one of Kilkenny City's main bridges, now has a timber-plank pedestrian bridge running beneath it, which is the longest of its kind in Europe.[175][176]

Modern prose and art

Ossory features prominently in several works of historical fiction and non-fictional novels, by various authors. The politics of the kingdom at the time of the Norman Invasion have been written about in Diarmait King of Leinster (2006) by Nicholas Furlong, as well as by historian and two-time chairman of the Irish Writers' Union, Conor Kostick in Strongbow: the Norman Invasion of Ireland (2013).[177] Ossory plays a role in some of the Sister Fidelma mysteries, most notably Suffer Little Children (1995) and The Seventh Trumpet (2012) written by Peter Tremayne (the pseudonym for Peter Berresford Ellis).[178] Author Morgan Llywelyn, who has written extensively in the genre of medieval Irish historical fiction, often mentions Ossory in her books; especially in Lion of Ireland (1980), its sequel Pride of Lions (1996), Strongbow: The Story of Richard & Aoife (1996)[179] and 1014: Brian Boru & the Battle for Ireland (2014).[180] Tavia Osraige is the name of a fictional character in the novel Rainseeker (2014) by Jeanette Matern.[181] Some battles which took place in the kingdom of Ossory during the Norman Invasion of Ireland, as well as the arrival of William Marshal are commemorated in pictorial form in the modern Ros Tapestry.[182][183]

Games

Because of its strategic position, Ossory often features in modern games which make use of territorial maps of Ireland. The kingdom of Ossory features as a part of the kingdom of Ireland in the computer strategy-games Crusader Kings and Crusader Kings II, both published by Paradox Interactive.[184][185] Historic wargamers have aimed to re-create the pivotal battle of Achadh Úr (present-day Freshford, County Kilkenny) between the invading Cambro-Normans and the defending Ossorians.[186] Ossory also appears as a kingdom in a map of medieval Ireland from Conquer Club.[187] Additionally, the name of the kingdom and some of its symbolic elements appear to have been the inspiration for fictional nation-states in role-playing forums.[188]

News

In 2014, a man from Mooncoin, Co. Kilkenny, laid a claim to residency in Kilkenny Castle as a supposed direct descendant of the kings of Osraige.[189][190] In late February 2017, Kilkenny's new Medieval Mile Museum opened to the public, giving visitors a history of the kingdom, and featuring an exhibit which highlights king Cerball's role as a powerful patron of Osraige's early high cross carving tradition.[191]

See also

- Baron Upper Ossory

- Bishop of Ossory

- Earl of Ossory

- Earl of Upper Ossory

- Fitzpatrick (surname)

- The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland

- History of Kilkenny

- History of Laois

- Kilkenny Archaeological Society

- Kings of Leinster

- Kings of Osraige

References

- ^ Genealogies from Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson B 502 and the Book of Leinster

- ^ Annals of Loch Cé 1193.13, Four Masters 1194.6

- ^ "Osraige pronunciation: How to pronounce Osraige in Irish". Forvo.com. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Collectanea de rebus hibernicis. 1790. pp. 331–.

- ^ Byrne, Irish kings and high-kings, maps on pp. 133 & 172–173; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 236, map 9 & p. 532, map 13.

- ^ "O'Lochlainn's 1940 map". Historyatgalway.files.wordpress.com. Archived from the original (JPG) on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Metrical Dindshenchas". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Roads, Bridges and Causeways in Ancient Ireland". libraryireland.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1907). The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. The Society. p. 26. ISSN 0035-9106. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502, at CELT, pg 15–16

- ^ a b "Cσir Anmann: Fitness of Names". Maryjones.us. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Byrne, p. 201

- ^ Ó Néill, 'Osraige'; Doherty, 'Érainn'

- ^ Byrne, p. 163

- ^ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 541

- ^ Ptolemy's map of Ireland: a modern decoding. R. Darcy, William Flynn. Irish Geography Vol. 41, Iss. 1, 2008. Figure 1.

- ^ "Heritage Discoveries: The Roman Burial from Stoneyford, Co. Kilkenny". culturalheritageireland.ie. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The Tri-River Region: The geographic key to lasting change in Ireland | Eóghan Mac Giolla Phádraig". Academia.edu. 1 January 1970. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Expulsion of the Déssi". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Chapter 4 : The Mabinogi of Manawyden : The Expulsion of the Déisi" (PDF). Mabinogi.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Charles-Edwards 2000

- ^ CS583

- ^ "Lebor na cert = The Book of rights". Archive.org. 21 July 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, FA4

- ^ Sharpe, O' Riain, and Sperber

- ^ "C. O Drisceoil 2013 Excavation and monitoring in Saint Canice's Cathedral Graveyard 2013 (Kilkenny Archaeology) | Cóilín Ó Drisceoil". Academia.edu. 1 January 1970. Archived from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "History of Kilkenny". Irishwalledtownsnetwork.ie. 18 January 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kings of Osraige". Sbaldw.home.mindspring.com. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 576

- ^ Annals of Ulster, AU 769.1

- ^ AU 770.2

- ^ U744.1

- ^ AU825.12

- ^ E. Kelly with J. Maas. Vikings on the Barrow: Dunrally Fort, a possible Viking Longphort in Co. Laois. In Archaeology Ireland; vol. 9, no. 3. (1995)

- ^ Created by Fuel.ie in Dublin. "Four Courts Press | Woodstown". Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Vikings and the kingdom of Laois. In Pádraig G. Lane and William Nolan, (eds.), Laois History & Society, Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County, (Dublin, 1999), pp 123-159. | Eamonn Kelly". Academia.edu. 1 January 1970. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Annals of St Bertin". Classesv2.yale.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Annals of Ulster 859.3

- ^ Fragmentary Annals of Ireland 265, and 268

- ^ Donnchadh Ó Corráin. "Viking Ireland—Afterthoughts" (PDF). Ucc.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ For claims of Ossorian attacks on the homeward-bound Dalcassians, see: Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib, Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, and Meredith Hanmer's Chronicle of Ireland.

- ^ Lyng, p.260-1

- ^ M1085.10

- ^ M1114.12

- ^ Robert King. A memoir introductory to the early history of the primacy of Armagh. p. 83. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ U1103.5

- ^ Carrigan, W. (1905). The history and antiquities of the diocese of Ossory. Vol. 1. Sealy, Bryers & Walker. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ M1154.15

- ^ M1156.17

- ^ M1157.10

- ^ MCB1167.4

- ^ MCB1167.6

- ^ MCB1167.9

- ^ MCB1169.2

- ^ "Google Play". Play.google.com. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "WWW.Freshford.com". freshford.yolasite.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Google Play". Play.google.com. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Lyng. The Fitzpatricks of Ossory, p. 260.

- ^ MCB1172.2

- ^ National Manuscripts of Ireland: Account of Facsimiles of National ... - Ireland. Public Record Office. p. 1. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ LC1193.13

- ^ FM1194.6

- ^ "Google Play". Play.google.com. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "The Kingdoms of Ossory". gerdooley.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ LC1269.6

- ^ "County Kilkenny - Geography Publications | Specialising in books of Irish history, geography and biography". Geography Publications. 18 December 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ O'Brien, Niall (24 February 2015). "Medieval News: Thomas Fitz Anthony: Thirteenth century Irish administrator". Celtic2realms-medievalnews.blogspot.ie. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Thomas Fitz Anthony: Thirteenth century Irish administrator | Niall C.E.J. O Brien". Academia.edu. 1 January 1970. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Edwards, David. "Collaboration without Anglicization: The Macgiollapadraig Lordship and Tudor Reform." Gaelic Ireland: c. 1250 – c. 1650: Land, Lordship & Settlement.(2001) p.77-97.

- ^ "County Kilkenny Ireland – History Timeline". rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Book of Rights". maryjones.us. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Part 2 of Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Part 39 of The History of Ireland". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fragmentary Annals of Ireland". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ireland's History in Maps - Ancient Ossory, Osraige, Osraighe". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. 25 October 2003. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Annals of Ulster 1033.4, Annals of Loch Cé 1033.3, Annals of Tigernach 1033.5

- ^ "Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, Annals of Ulster, Annals of the Four Masters

- ^ a b Landnámabók

- ^ Cogadh Gaedhel Re Gallaibh (trans. by Todd) pg 297

- ^ "Landnámabók (Sturlubók)". snerpa.is. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ AI 983.4 and AI 984.2

- ^ AU 1016.6; ALC 1016.4; CS, s.a. 1014; AFM, s.a. 1015

- ^ AT 1022.2; CS, s.a. 1020; AFM, s.a. 1022

- ^ AI 1026.3

- ^ AU 1027.2; ALC 1027.2; AT 1027.2; AFM, s.a. 1027; Ann. Clon., s.a. 1027

- ^ AU 1033.4; ALC 1033.3; AFM, s.a. 1033

- ^ AT 1039.6; AFM, s.a. 1039

- ^ AU 1039.2; ALC 1039.2; AT 1039.7; AI 1039.7 only calls Donnchad king of Osraige; after a long illness, AFM, s.a. 1039; Ann. Clon., s.a. 1039

- ^ The Annals of Tigernach; T1098.1

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "On the Life of St. Patrick". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ John Francis Shearman. Loca Patriciana: An Identification of Localities, Chiefly in Leinster ... p. 391. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (This wikisource is partially out-dated.) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Page not found – Cornwall Council". cornwall.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Kilkenny – Cill Chainnigh – Saints Patrick and Kieran". vanderkrogt.net. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Topography of Ireland" (PDF). Yorku.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dmitry Lapa. Holy Father Modomnoc of Ossory, Patron Saint of Bees. Commemorated: February 13/26 / OrthoChristian.Com". pravoslavie.ru. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee: Félire Óengusso Céli dé". archive.org. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b "The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Hymn to Saint Brigid of Brogan-Cloen from the Liber Hymnorum (Broccan's Hymn) – YouTube". youtube.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stokes, W. (1905). Feĺire Ońgusso Ceĺi De.́: The Martyrology of Oengus, the Culdee. Harrison and sons, printers. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Kyle (clonfert-mulloe), County Laois". earlychristianireland.net. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Clonfertmulloe". megalithicireland.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kyle (Clonfert Mulloe) · The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain & Ireland". crsbi.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The history and antiquities of the diocese of Ossory". archive.org. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "St Molua's Online". stormont.down.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tweeting Saints in Medieval Irish Martyrologies -February (with images) · PeritiaEditors · Storify". storify.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee". ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Healy, J. (1905). The Life and Writings of St. Patrick: With Appendices, Etc. M. H. Gill & son, Limited. p. 408. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Bethada Náem nÉrenn". ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cathedral Church of St Canices and Round Tower- Visitor Attraction in Kilkenny". stcanicescathedral.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [2]

- ^ Lyng, T., The FitzPatricks of Ossory, Old Kilkenny Review, Vol. 2, no. 3, 1981; pg. 261.

- ^ Nancy Edwards (1982). "A reassessment of the early medieval stone crosses and related stone sculpture of Offaly, Kilkenyn and Tipperary" (PDF). Etheses.dur.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Seirkieran". irishantiquities.bravehost.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Frank Schorr. "Seir Kieran Irish Round Tower". roundtowers.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ National Monuments Service

- ^ Early Christian Sites In Ireland Database

- ^ "Cathedral Church of St Canices and Round Tower- Visitor Attraction in Kilkenny". stcanicescathedral.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cóilín Ó Drisceoil. "Probing the past: a geophysical survey at St. Canice's Cathedral, Kilkenny." Old Kilkenny Review No. 58 (2004) p. 80-106. Print.

- ^ a b Brenda Lynch. Jerpoint Abbey: an historical perspective." Old Kilkenny Review No. 58 (2004) p. 125-138. Print.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Buckley, Laureen. "Dunmore Cave – A Viking Massacre Site". Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ M928.9

- ^ "Ossary Bridge – main page". smithsculptors.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Nore and its Bridges" (PDF). Heritageinschools.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Part 90 of The History of Ireland". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Downham, "Career", p. 7; Mac Niocaill, Ireland before the Vikings, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Downham, "Career", p. 7; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp. 292–294; Byrne, Irish kings and high-kings, pp. 180–181.

- ^ "The Lives of Saint Ciarán, Patron of the Diocese of Ossory"; Pádraig Ó Riain, in Ossory, Laois and Leinster vol. 3. p. 25

- ^ "Monasticon Hibernicum". monasticon.celt.dias.ie. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Irish Tribes" (PDF). Irishtribes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fragmentary Annals of Ireland". ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Joan N. Radner (ed. & trans.) Fragmentary Annals of Ireland (Dublin 1978)

- ^ "Fragmentary Annals of Ireland". ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cogadh Gaedhel Re Gallaibh. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindshenchas II – Translation [text]". ucd.ie. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Metrical Dindshenchas". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Banshenchus". Maryjones.us. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Google Play". Play.google.com. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Uí Bairrche (Leinster) - Page 2". TraceyClann. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ James B. Dollard. Poems. p. 25. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Edward Hayes (ed.). The Ballads of Ireland. Vol. 1. p. 232. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "James Clarence Mangan – Books on Google Play". play.google.com. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to the Prince of Ossory". ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brennu-Njáls saga – Icelandic Saga Database". sagadb.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Icelandic Sagas, Volume 3 : The Orkneyingers' Saga". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Juxtaposing Cogadh Gáedel re Gallaib with Orkneyinga saga, by Thomas A. DuBois. In Oral Tradition Vol. 26, Number 2 (October 2011) p. 286. PDF available here: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.