Pennsylvania Railroad

| |

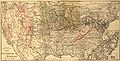

PRR system map, circa 1918 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Reporting mark | PRR |

| Locale | Delaware Illinois Indiana Kentucky Maryland Michigan New Jersey New York Ohio Pennsylvania Washington, DC West Virginia |

| Dates of operation | 1846–1968 |

| Successor | Penn Central Transportation Company |

| Technical | |

| Previous gauge | at one time 4 ft 9 in (1,448 mm) |

| Electrification | 12.5kV 25Hz AC: New York City-Washington, D.C./South Amboy; Philadelphia-Harrisburg; North Jersey Coast Line |

| Length | 10,512 miles (16,917 kilometers) |

| Other | |

| Website | prrths.com |

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR) was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy," the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The PRR was the largest railroad by traffic and revenue in the U.S. for the first half of the twentieth century. Over the years, it acquired, merged with or owned part of at least 800 other rail lines and companies.[1] At the end of 1925, it operated 10,515 miles of rail line;[2] in the 1920s, it carried nearly three times the traffic as other railroads of comparable length, such as the Union Pacific or Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railroads. Its only formidable rival was the New York Central (NYC), which carried around three-quarters of PRR's ton-miles.

At one time, the PRR was the largest publicly traded corporation in the world, with a budget larger than that of the U.S. government and a workforce of about 250,000 people.[3] The corporation still holds the record for the longest continuous dividend history: it paid out annual dividends to shareholders for more than 100 years in a row.[4]

In 1968, PRR merged with rival NYC to form the Penn Central Transportation Company, which filed for bankruptcy within two years.[5] The viable parts were transferred in 1976 to Conrail, which was itself broken up in 1999, with 58 percent of the system going to the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS), including nearly all of the former PRR. Amtrak received the electrified segment east of Harrisburg.

History

Main Line

Background

With the opening of the Erie Canal (1825) and the beginnings of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (1828), Philadelphia business interests became concerned that the port of Philadelphia would lose traffic. The state legislature was pressed to build a canal across Pennsylvania and thus the Main Line of Public Works was commissioned in 1826.[6] It soon became evident that a single canal would not be practical and a series of railroads, inclined planes, and canals was proposed.[7] The route consisting of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, canals up the Susquehanna and Juniata rivers, an inclined plane railroad and tunnel across the Allegheny Mountains, and canals down the Conemaugh and Allegheny rivers to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River was completed in 1834. Because freight and passengers had to change cars several times along the route and canals froze during the winter, it soon became apparent that the system was cumbersome and a better way was needed.[7][8]

Early history

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted a charter to the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1846 to build a private rail line that would connect Harrisburg to Pittsburgh.[9] The Directors chose John Edgar Thomson, an engineer from the Georgia Railroad, to survey and construct the line. He chose a route that followed the west bank of the Susquehanna River northward to the confluence with the Juniata River, following its banks until the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains were reached at a point that would become Altoona, Pennsylvania.[7] In order to traverse the mountains, the line climbed a moderate grade for 10 miles until it reached a split of two mountain ravines which were cleverly crossed by building a fill and having the tracks ascend a 220-degree curve that limited the grade to less than 2 percent. The crest of the mountain was penetrated by the 3,612-foot Gallitzin Tunnels and then descended by a more moderate grade to Johnstown.

The western end of the line was simultaneously built from Pittsburgh east along the banks of the Allegheny and Conemaugh rivers to Johnstown. PRR was granted trackage rights over the Philadelphia and Columbia and gained control of the three short lines connecting Lancaster and Harrisburg, instituting an all-rail link between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh by 1854. In 1857, the PRR purchased the Main Line of Public Works from the state of Pennsylvania, and abandoned most of its canals and inclined planes. The line was double track from its inception and by the end of the century a third and fourth track were added. Over the next 50 years, PRR would expand by gaining control of other railroads by stock purchases and 999-year leases.[8] This line is still an important cross-state corridor, carrying Amtrak's Philadelphia to Harrisburg Main Line and the Norfolk Southern Railway's Pittsburgh Line.

John Edgar Thomson (1808–1874) was the entrepreneur who led the PRR from 1852 to his death in 1874, making it the largest business enterprise in the world and a world-class model for technological and managerial innovation. He served as PRR's first Chief Engineer and third President.[10] Thomson's sober, technical, methodical, and non-ideological personality had an important influence on the Pennsylvania Railroad, which in the mid-19th century was on the technical cutting edge of rail development, while nonetheless reflecting Thomson's personality in its conservatism and its steady growth while avoiding financial risks. His Pennsylvania Railroad was in his day the largest railroad in the world, with 6,000 miles of track, and was famous for steady financial dividends, high quality construction, constantly improving equipment, technological advances (such as replacing wood with coal), and innovation in management techniques for a large complex organization.[11]

New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington lines

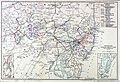

November 3, 1857

In 1861 the PRR gained control of the Northern Central Railway, giving it access to Baltimore, Maryland, as well as points along the Susquehanna River via connections at Columbia, Pennsylvania or Harrisburg.[12]

On December 1, 1871, the PRR leased the United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company, which included the original Camden and Amboy Railroad from Camden, New Jersey (across the Delaware River from Philadelphia) to South Amboy, New Jersey (across Raritan Bay from New York City), as well as a newer line from Philadelphia to Jersey City, New Jersey, much closer to New York, via Trenton, New Jersey. Track connection in Philadelphia was made via the PRR's Connecting Railway and the jointly owned Junction Railroad (Philadelphia).[13]

The PRR's Baltimore and Potomac Rail Road opened on July 2, 1872, between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. This route required transfer via horse car in Baltimore to the other lines heading north from the city. On June 29, 1873, the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel through Baltimore was completed. The PRR started the misleadingly named Pennsylvania Air Line service via the Northern Central Railway and Columbia, Pennsylvania. This service was 54.5 miles (87.5 km) longer than the old route but avoided the transfer in Baltimore. The Union Railroad (Baltimore) line opened on July 24, 1873. This route eliminated the transfer in Baltimore. PRR officials contracted with both the Union Railroad and the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) Railroad for access to this line. The PRR's New York–Washington trains began using the route the next day, ending Pennsylvania Air Line service. In the early 1880s, the PRR acquired a majority of PW&B Railroad's stock. This action forced the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) to build the Baltimore and Philadelphia Railroad to keep its Philadelphia access, where it connected with the Reading Railroad for its competing Royal Blue Line passenger trains to reach New York.

In 1885, the PRR began passenger train service from New York City via Philadelphia to Washington with limited stops along the route. This service became known as the "Congressional Limited Express."[citation needed] The service expanded, and by the 1920s, the PRR was operating hourly passenger train service between New York, Philadelphia and Washington. In 1952, 18-car stainless steel streamliners were introduced on the Morning Congressional and Afternoon Congressional between New York and Washington, as well as the Senator from Boston to Washington.[14]

New York-Chicago

On July 1, 1869 the Pennsylvania Railroad leased the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway in which it had previously been an investor. The lease gave the PRR complete control of that line's direct route through northern Ohio and Indiana as well as entry into the emerging rail hub city of Chicago, Illinois. Acquisitions along the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway: Erie and Pittsburgh Railroad, Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad, Toledo, Columbus and Ohio River Railroad, and Pittsburgh, Youngstown and Ashtabula Railway gave the PRR access to the iron ore traffic on Lake Erie.[8]

On June 15, 1887 the Pennsylvania Limited began running between New York and Chicago. This was also the introduction of the vestibule, an enclosed platform at the end of each passenger car, allowing protected access to the entire train. In 1902 the Pennsylvania Limited was replaced by the Pennsylvania Special which in turn was replaced in 1912 by the Broadway Limited which became the most famous train operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[15][16] This train ran from New York City to Chicago, via Philadelphia, with an additional section between Harrisburg and Washington (later operated as a separate Washington–Chicago train, the Liberty Limited).

New York-St. Louis

In 1890 the PRR gained control of the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad commonly called the Panhandle Route a line that ran west from Pittsburgh to Bradford, Ohio, where it split, with one line to Chicago and the other to East St. Louis, Illinois via Indianapolis, Indiana. This railroad company was the result of the merger of numerous smaller lines in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The last line to be added was the Vandalia Railroad which Gave the PRR access to St. Louis, Missouri.[8]

The line was double-tracked for much of its length serving the coal region of southern Illinois and as a passenger route for the Pennsylvania Railroad's Blue Ribbon named trains The St Louisan, the Jeffersonian, and the Spirit of St. Louis.[17]

"Low-grade" lines

Around 1900, the PRR built several low-grade lines for freight to bypass areas of steep grade (slope). These included:

- 1892: Trenton Branch (PRR) and Trenton Cut-Off Railroad from Glen Loch, Pennsylvania east to Morrisville, Pennsylvania (not only a low-grade line but a long-distance bypass of Philadelphia and shortcut)

- 1892: Waverly and Passaic Railroad (finished by the New York Bay Railroad) from Waverly, New Jersey to Kearny, New Jersey

- 1904: Reopening of the New Portage Railroad from the Gallitzin Tunnels east to New Portage Junction (abandoned), then continuing north over the Hollidaysburg Branch to Altoona

- 1906: Philadelphia and Thorndale Branch from Thorndale, Pennsylvania east to Glen Loch (abandoned by Conrail in 1989)

- 1906: Atglen and Susquehanna Branch from Harrisburg via the Northern Central Railway south to Wago Junction, then east to Parkesburg (the latter abandoned by Conrail in 1990)

The Pennsylvania and Newark Railroad was incorporated in 1905 to build a low-grade line from Morrisville, Pennsylvania to Colonia, New Jersey. It was never completed, but some work was done in the Trenton area, including bridge piers in the Delaware River. North of Colonia, the alignment was going to be separate, but instead two extra tracks were added to the existing line. Work was suspended in 1916. Another low-grade line across the mountains of Pennsylvania, avoiding completely the congestion of Pittsburgh, was contemplated but never saw the light of day.

Pennsylvania Railroad electrification

Early in the 20th century the PRR tried electric power for its trains. First was the New York terminal area, where tunnels precluded steam locomotives; a direct current (DC) 650-volt third rail powered PRR locomotives (and LIRR passenger cars). The system was put into service in 1910.[18]

The next area to be electrified was the Philadelphia terminal area, where PRR officials decided to use overhead lines to supply power to the suburban trains running out of Broad Street Station. Unlike the New York terminal system, overhead wires would carry 11,000-volt 25-Hertz alternating current (AC) power: the system used for all future installations. In 1915, electrification of the line from Philadelphia to Paoli, Pennsylvania was completed.[19] Other Philadelphia lines electrified were the Chestnut Hill Branch (1918), White Marsh (1924), West Chester (1928), the main line to Wilmington, Delaware, and in 1930 the Schuylkill Branch to Norristown, along with the rest of the main line to Trenton.

PRR's president William Wallace Atterbury announced in 1928 plans to electrify the lines between New York, Philadelphia, Washington and Harrisburg. In January 1933, through main-line service between New York and Philadelphia/Wilmington/Paoli was placed in operation. The first test run of an electric train between Philadelphia and Washington occurred on January 28, 1935. On February 1 the Congressional Limiteds in both directions were the first trains in regular electric operation between New York and Washington, drawn by the first of the GG1-type locomotives. All regular passenger trains between these cities were electrified by March 15.

In 1934 the PRR received a $77 million loan from the New Deal's Public Works Administration [20] To complete the electrification project initiated in 1928, work was started January 27, 1937, on the main line from Paoli to Harrisburg; the low-grade freight line from Morrisville through Columbia to Enola Yard in Pennsylvania; the Port Road Branch from Perryville, Maryland to Columbia; the Jamesburg Branch and Amboy Secondary freight line from Monmouth Junction to South Amboy; and the Landover-South End freight line from Landover, Maryland through Washington to Potomac Yard in Alexandria, Virginia (now called the Landover Subdivision and RF&P Subdivision of CSX). In less than a year, on the following January 15, the first passenger train, the Metropolitan, went into operation over the newly electrified line from Philadelphia to Harrisburg. On April 15 the electrified freight service from Harrisburg and Enola Yard east was inaugurated, thus completing the Pennsy's eastern seaboard electrification program with a total of 2,677 miles (4,308 km) of track electrified—41 percent of the total electrically operated standard railroad trackage of the United States. Portions of the electrified trackage are still in use, owned and operated by Amtrak as the Northeast Corridor and Keystone Corridor high-speed rail routes,[21] by SEPTA, and by PATH.

Penn Central merger and Conrail

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 48,890 |

| 1933 | 26,818 |

| 1944 | 71,249 |

| 1960 | 42,775 |

| 1967 | 50,730 |

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 4,518 |

| 1933 | 2,017 |

| 1944 | 13,047 |

| 1960 | 2,463 |

| 1967 | 1,757 |

On February 1, 1968 the PRR merged with its arch-rival, the New York Central railroad, to form the Penn Central. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) required that the ailing New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad be added in 1969. A series of events including inflation, poor management, abnormally- harsh weather conditions and the withdrawal of a government-guaranteed 200-million-dollar operating loan forced the Penn Central to file for bankruptcy protection on June 21, 1970.[5] The Penn Central rail lines were split between Amtrak (Northeast Corridor and Keystone Corridor) and Conrail in the 1970s.

After the breakup of Conrail in 1999, the portion which had been PRR territory largely became part of the Norfolk Southern Railway. The few parts of the PRR that went to CSX after the Conrail split are (1) the western end of the Fort Wayne Line across western Ohio and northern Indiana, (2) the Pope's Creek Secondary in Maryland, just to the east of Washington, (3) the Landover Subdivision, a former Pennsy freight line in DC which connects to Amtrak's ex-Pennsy Northeast Corridor and CSX's ex-B&O Alexandria Extension on the north end and CSX's RF&P Subdivision on the south end via the ex-Pennsy "Long Bridge" across the Potomac River, and (4) the Terre Haute, Ind.-to-East St. Louis, Ill. segment of the St. Louis main line (the segment east of Terre Haute is former-New York Central).

Timeline

- 1846: PRR is chartered to construct a rail line from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

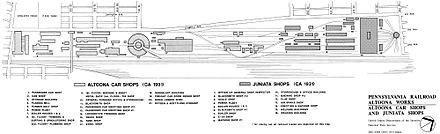

- 1850: Construction begins on Altoona Works repair shop at Altoona, Pennsylvania.

- 1860–1890: PRR expands throughout the eastern U.S.

- 1869: PRR leases the Pittsburgh, Ft. Wayne & Chicago, formally giving it control of a direct route into the heart of the Midwest.

- 1885: The Congressional Limited Express from New York City-Washington, D.C. is introduced.

- 1887: Pennsylvania Limited service begins between New York-Chicago; first vestibuled train.[24]

- 1894: The Pennsylvania Pacific Corporation is formed by the PRR.

- 1902: Pennsylvania Special service begins between New York and Chicago replacing the Pennsylvania Limited.[25]

- 1906: An accident in Atlantic City kills 53 people

- 1910: Completion of the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River, providing direct service from New Jersey to Manhattan on electrified lines, terminating at the massive new Penn Station

- 1912: Broadway Limited was inaugurated, replacing the Pennsylvania Special.

- 1915: PRR electrifies its suburban Philadelphia lines to Paoli, Pennsylvania.

- 1916: PRR adopts new motto, Standard Railroad of the World. The first I1s Decapod locomotive is completed, and switching locomotives of the A5s and B6sb class are introduced.

- 1917: Completion of the New York Connecting Railroad and the Hell Gate Bridge

- 1918: PRR stock bottoms at $40¼ (equal to $815.33 today), the lowest since 1877, due largely to Federal railroad control. Emergency freight is routed through New York Penn Station and the Hudson River tunnels by the USRA to relieve congestion. Locomotive class N1s is introduced for PRR's western lines; PRR electrifies suburban commuter line to Chestnut Hill.

- 1928–1938: PRR electrifies its New York–Washington, D.C. and Chicago–Philadelphia line between Harrisburg and Paoli, several Philadelphia and New York area commuter lines, and major through freight lines.

- 1943: An accident at Frankford Junction, Pennsylvania kills 79.

- 1946: PRR reported a net loss for the first time in its history.[26]

- 1951: An accident in Woodbridge, New Jersey kills 85 people.

- 1957: Steam locomotives are removed from active service in the PRR fleet.

- 1968: PRR merges with NYC to form the Penn Central Transportation Company (PC).

Equipment

The PRR's corporate symbol was the keystone, the commonwealth of Pennsylvania's state symbol, with the letters "PRR" intertwined inside. When colored, it was bright red with a silver-grey inline and lettering.

Paint schemes

As noted, PRR colors and paint schemes were standardized. Locomotives were painted in a shade of green so dark it seemed almost black. The official name for this color was DGLE (Dark Green Locomotive Enamel), though often referred to as "Brunswick Green." The undercarriage of the locomotives were painted in black, referred to as "True Black." The passenger cars of the PRR were painted Tuscan Red, a brick-colored shade of red. Some electric locomotives and most passenger-hauling diesel locomotives were also painted in Tuscan Red. Freight cars of the PRR had their own color, known as "Freight Car Color," an iron-oxide shade of red. On passenger locomotives and cars the lettering and outlining was originally done in real gold leaf. After World War II the lettering was done in a light shade of yellow called Buff Yellow.[27]

Signaling

PRR was one of the first railroads to replace semaphore signals with position-light signals.[28] Such signals, which featured a large round target with up to eight amber-colored lights in a circle and one in the center, could be lit in various patterns to convey different meanings, were more visible in fog, and remained effective even when one light in a row was inoperative.[29]

Signal aspects, or meanings, were displayed as rows of three lit lights. The aspects corresponded with upper-quadrant semaphore signal positions: vertical for "proceed", a 45° angle rising to the right for "approach", horizontal for "stop", a 45° angle rising to the left for "restriction", a "X" shape for "take siding", and a full circle (used in in electrified territory) for "lower pantograph". Additional aspects were conveyed with a second target head below the first, either a single light, a partial target, or a full target. Separate Manual Block signal aspects existed as well.[29]

In later years, interlocking home signals north and west of Rockville (near Harrisburg) were modified so that the two outside lights in the horizontal "stop" row had red lenses; the center lamp would be extinguished when the signal displayed "stop".[29] Such "red-eye" lenses were also temporarily installed at Overbrook Interlocking near Philadelphia.[29]

Starting in the late 1920s, the PRR installed Pulse code cab signaling along certain tracks used by high-speed passenger trains. Information traveled through the rails using track circuits, was picked up by a sensor on the locomotive, and displayed in the engineer's cab. PRR ultimately installed cab signals on its New York-Washington, Philadelphia-Pittsburgh, and Pittsburgh-Indianapolis lines (the latter which was later downgraded by PC and ultimately abandoned by Conrail). PRR also experimented with cab signals without wayside signals, an approach later expanded by Conrail (Conemaugh line) and Norfolk Southern Railway (Cleveland line). Cab signals were subsequently adopted by several other U.S. railroads, especially on passenger lines. This technology, advanced for its time, is still used by Amtrak.[29]

Steam locomotives

For most of its existence, PRR was conservative in its locomotive choices and pursued standardization, both in locomotive types and their component parts.[30] Almost alone among U.S. railroads, the PRR designed most of its steam locomotive classes itself. It built most of them in Altoona, outsourcing only when PRR facilities could not keep up with the railroad's needs. In such cases, subcontractors were hired to build to PRR designs,[31] unlike most railroads that ordered to broad specifications and left most design choices to the builder.[30]

The PRR's favorite outsourcer was Baldwin Locomotive Works, which received its raw materials and shipped out its finished products on PRR lines. The two companies were headquartered in the same city; PRR and Baldwin management and engineers knew each other well. When the PRR and Baldwin shops were at capacity, orders went to the Lima Locomotive Works in Lima, Ohio.[31] Only as a last resort would the PRR use the American Locomotive Company (Alco), based in Schenectady, New York, which also built for PRR's rival, NYC.

The PRR had a design style that it favored in its locomotives. One example was the square-shouldered Belpaire firebox. This British-style firebox was a PRR trademark that was rarely used by other locomotive builders in the U. S. PRR also used track pans extensively to retrieve water for the locomotive while in motion. Using this system meant that the tenders of their locomotives had a comparatively large proportion of coal (which could not be taken on board while running) compared to water capacity. Locomotives of the PRR had a clean look to them. Only necessary devices were used and they were mounted neatly on the locomotive.[30] Smoke box fronts bore a round locomotive number board denoting a freight locomotive or a keystone number board denoting a passenger locomotive. Otherwise the smoke box was uncluttered except for a headlamp at the top and a steam-driven turbo-generator behind it. In later years the positions of the two were reversed, since the generator needs more maintenance than the lamp.[30]

Each class of steam locomotive was assigned a class designation.[28] Early on this was simply a letter, but when these ran short the scheme was changed so that each wheel arrangement had its own letter, and different types in the same arrangement had different numbers added to the letter. Subtypes were indicated by a lower-case letter; superheating was designated by an "s" until the mid-1920s, by which time all new locomotives were superheated. A K4sa class was a 4-6-2 "Pacific" type (K) of the fourth class of Pacifics designed by PRR. It was superheated (s) and was of the first variant type (a) after the original (unlettered). Steam locomotives remained part of the PRR fleet until 1957.

PRR's reliance on steam locomotives in the mid-20th century contributed to its decline. Steam locomotives require more maintenance than diesel locomotives, are less cost efficient, and require more personnel to operate. PRR was unable to update its roster during the World War II years; by the end of the war their roster was in rough shape. In addition, PRR was saddled with unsuccessful experimental steam locomotives such as the Q1, S1, and T1 "Duplex Drive" locomotives, and the S2 turbine locomotive. Unlike most of their competition, PRR did not acquire any 4-8-4 locomotives.

PRR's competitors managed this period better with their diesel locomotive rosters.[3] PRR voluntarily preserved a roundhouse full of representative steam locomotives at Northumberland, Pennsylvania in 1957 and kept them there for several decades. These locomotives, with the exception of I1sa #4483 which is on display at Hamburg, New York, are now at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, Pennsylvania. In sharp contrast, NYC's Alfred E. Perlman deliberately scrapped all but two large steam locomotives, and these survived only by accident.

On December 18, 1987 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania designated PRR's K4s as the official State Steam Locomotive. The two surviving Locomotives are housed at Strasburg and Altoona.[32]

Electric locomotives

When work on the Hudson River tunnels and New York's Penn Station was in progress, the type of electric locomotives to be used was an important consideration. At that time only a few electric locomotives existed. Several experimental locomotives were designed by railroad and Westinghouse engineers and tried on the West Jersey & Seashore Railroad track. From these tests the DD1 class was developed.[18] The DD1s were used in pairs (back to back). Thirty-three of these engines having Westinghouse equipment were built at Altoona. They were capable of speeds up to 85 miles per hour (137 km/h). Placed in service in 1910, they proved to be quite efficient.[citation needed]

Steel suburban passenger cars capable of being electrified for MU operation were designed due to the need for such cars in service to Penn Station through its associated tunnels and were designated MP54.[33] Designs for corresponding cars accommodating baggage and mail were produced also. Eight of these cars were electrified with DC equipment to provide shuttle service from Penn Station to Manhattan Transfer between 1910 and 1922. More extensive electrification plans required AC electrification, starting with 93 cars for the Paoli Line in 1915. With the expansion of the AC electrification, additional MP54 cars were electrified or purchased new until a total of 481 cars was reached in 1951. Replacement with newer types of cars began in 1958 and the last MP54 cars were retired in 1980.[citation needed]

The single FF1 appeared in 1917 and ran experimentally for a number of years in preparation for electrification over the Allegheny Mountains that never came to fruition. Its AC induction motors and side-rod drive powered six axles.[18] It developed a starting tractive force of 140,000 pounds, which was capable of ripping couplers out of the fragile wooden freight cars in use at the time.[34]: 123

In 1924 another side-rod locomotive was designed: (the L5 class).[18] Two DC locomotives were built for the New York electrified zone and a third, road number 3930, was AC-equipped and put in service at Philadelphia. Later 21 more L-5 locomotives were built for the New York service. A six-wheeled switching engine was the next electric motive power designed, being classified as B1.[18] Of the first 16 AC engines, two were used at Philadelphia and 14 on the Bay Ridge line, while 12 DC-equipped engines were assigned to Sunnyside Yard in Queens, New York.

The O1 class was a light passenger type.[18] Eight of these engines were built from June 1930 to December 1931. The P5 class was also introduced, with two of this class being placed in service during July and August 1931.[35] Following these came the P5A, a slightly heavier design capable of traveling 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) and with a tractive force of 56,250 pounds. In all, 89 of these locomotives were built. The first had a box cab design and were placed in service in 1932. The following year, the last 28 under construction were redesigned to have a streamlined type of cab. Some engines underwent regearing for freight service.[citation needed]

In 1933 two entirely new locomotives were being planned: the R1 and the GG1 class. The R-1 had a rigid frame for its four driving axles, while the GG-1 had two frames which were articulated. Both of these prototypes, along with an O-1, a P5A and a K4s steam locomotive underwent exhaustive testing. Testing was conducted over a special section of test track near Claymont, Delaware and lasted for nearly two years.[35] As a result of these experiments, the GG1 type was chosen and the construction of 57 locomotives was authorized. The first GG1 was finished in April and by August 1935 all 57 were completed. These first GG1 engines were designated for passenger service, while most of the P5A type were made available for freight service. Some of the later-built GG1s were assigned to freight service as well. The total number of GG1s built was 139. They are rated at 4,620 horsepower (3,450 kW) at speeds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[citation needed]

On August 26, 1999, the U.S. postal Service issued commemorative 33-cent All Aboard! 20th Century American Trains stamps. These commemorative stamps featured five celebrated American passenger trains from the 1930s and 1940s. One of the five stamps features an image of a GG-1 locomotive pulling the "Congressional Limited Express." The official Pennsylvania State Electric Locomotive is the GG-1 #4859. It received this designation on December 18, 1987 and is currently on display in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[32]

Diesel locomotives

In the mid-1940s, the PRR began to add diesel locomotives to their fleet. From 1945 through 1949 it purchased 60 E7 class locomotives from General Motors EMD (Electro-Motive Division). These units were given the classification EP20 by the PRR. Sixty of this number were designated "A" units, meaning that they had a cab for the train crew. The remaining 14 were designated "B" units; these were cabless booster units that were controlled by an "A" unit.[citation needed]

Another addition to the PRR diesel locomotive fleet was the Baldwin DR-12-8-1500/2, referred to as the "Centipede." Twenty-four of these units were purchased, and PRR classified them as BP60. These units had reliability problems and were soon obsolete. They were relegated to helper service.[citation needed]

In 1948 the PRR purchased twenty-seven DR-6 locomotives from Baldwin Locomotive Works. These units were given the PRR classification BP20. Originally for the passenger service fleet, these locomotive proved troublesome, and some were reclassified as BF16z freight locomotives.[citation needed]

From 1950–1952, the PRR purchased another group of 74 locomotives from EMD. These were EMD's E8 locomotives (successor to the E7). All of this group were "A" units. The PRR gave these units the classification EP22s. In 1956, the Pennsy opened bidding for a large order of diesel replacement locomotives. GM/EMD gave the PRR an exceptional deal on new, reliable GP9s, so the entire bid went to EMD. When this large diesel order arrived, the PRR was able to retire its entire remaining steam fleet, in 1957. Baldwin Locomotive Works (BLW) was counting on PRR (BLW's lifelong loyal customer) to keep the struggling company in business by purchasing at least some Baldwin diesels. When that did not happen, the 126-year-old company went bankrupt.[36]

Facilities

Altoona Works

In 1849, PRR officials developed plans to construct a repair facility at Altoona. Construction was started in 1850, and soon a long building was completed that housed a machine shop, woodworking shop, blacksmith shop, locomotive repair shop and foundry. This facility was later demolished to make room for continuing expansion. Additional PRR repair facilities were located in Harrisburg, Pittsburgh and Mifflin, and the Altoona Works expanded in adjacent Juniata, Pennsylvania. Inventor Alexander Graham Bell sent two assistants to the Altoona shops in 1875 to study the feasibility of installing telephone lines. In May 1877, telephone lines were installed for various departments to communicate with one another. Fort Wayne, Indiana, also held a key position for the railroad. By the turn of the 20th century, its repair shops and locomotive manufacturing facilities became known as the "Altoona of the West."[37]

By 1945 the Altoona Works had become one of the largest repair and construction facilities for locomotives and cars in the world.[38] During World War II, PRR facilities (including the Altoona Shops) were on target lists of German saboteurs. They were caught before they could complete their missions.[3]

In 1875 the Altoona Works started a testing department for PRR equipment. In following years, the Pennsylvania Railroad led the nation in the development of research and testing procedures of practical value for the railroad industry.[39] Use of the testing facilities was discontinued in 1968 and many of the structures were demolished.

Major passenger stations

The PRR built several grand passenger stations, alone or with other railroads. These architectural marvels, whose city name was usually preceded by "Penn Station", were the hubs for the PRR's passenger service. Many are still in use today, served by Amtrak and regional passenger carriers.

Broad Street Station – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Broad Street Station was the first of the great passenger stations built by the PRR. Opened in 1881, the station was expanded in the early 1890s by famed Philadelphia architect Frank Furness. For most of its existence it was with City Hall one of the crown jewels of Philadelphia's architecture, and until a 1923 fire had the largest train shed in the world (a 91 m span). It was the terminal for the PRR in Philadelphia, bringing trains into the center of the city. It was demolished in 1953 after the PRR moved to 30th Street Station.

30th Street Station – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

30th Street Station displays its majestic—and traditional—architectural style with its enormous waiting room and its vestibules. The station, in spite of its architectural classicism, opened in 1933, when modern and Art Deco styles were more popular. Its construction was needed to accommodate increased intercity and suburban traffic. It replaced the 32nd Street Station (West Philadelphia). It is now the primary rail station in Philadelphia, serving long-distance and commuter trains.

Penn Station – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Built 1898-1903, renovated in 1954 and partially repurposed in 1988, it was originally called "Union Station" as the terminal for some Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiaries.

Penn Station – Baltimore, Maryland

The main station of Baltimore, this Beaux-Arts building was built in 1911 from a design by architect Kenneth MacKenzie Murchison. It is currently served by Amtrak and MARC commuter service. Both approaches to the station are via tunnels, the B&P Tunnel to the south and the Union Tunnel to the north.

Union Station – Chicago, Illinois

The PRR, along with the Milwaukee Road and the Burlington Route, built Chicago's Union Station, the only one of Chicago's old stations still used as an intercity train station. It was designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White in the Beaux-Arts style.

Penn Station – Newark, New Jersey

Newark's Pennsylvania Station was designed by McKim, Mead and White. It opened in 1935, was completed in 1937 and was refurbished in 2007.[40] Its style is a mixture of Art Deco and Neo-Classical. All Amtrak trains stop here, and the station serves three commuter lines, PATH rapid transit to Jersey City and Manhattan, and the Newark Light Rail.

Penn Station – New York City, New York

The original Pennsylvania Station was designed by the noted architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White and was modeled on the Roman Baths of Caracalla; it was notable for its high vaulted ceilings. The station opened in 1910 to provide access to Manhattan from New Jersey without having to use a ferry, and was served by PRR's own trains as well as those of its subsidiary, the Long Island Rail Road. Infamously, the station was demolished for redevelopment in 1963. The only pieces to survive the demolition were the platforms, the tracks, and even some of the staircases. The station continues as an underground operation (serving Amtrak, New Jersey Transit and the LIRR) and is the busiest intercity railroad station in the United States.[41]

Union Station – Washington, D.C.

Union Station, built jointly with the B&O, served as a hub for PRR passenger services in the nation's capital, with connections to the B&O, and Southern Railway. The station was designed by architect Daniel Burnham and opened in 1908. The Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad provided a link to Richmond, Virginia, about 100 miles (160 km) to the south, where major north–south lines of the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line railroads provided service to the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida. Today Union Station is the location of Amtrak headquarters and serves Amtrak and regional commuter railroads (MARC and VRE).

Presidents

- Samuel V. Merrick (1847–1849)

- William C. Patterson (1849–1852)

- J. Edgar Thomson (1852–1874)

- Thomas A. Scott (1874–1880)

- George Brooke Roberts (1880–1896)

- Frank Thomson (1897–1899)

- Alexander J. Cassatt (1899–1906)

- James McCrea (1907–1912)

- Samuel Rea (1913–1925)

- William W. Atterbury (1925–1935)

- Martin W. Clement (1935–1948)

- Walter S. Franklin (1948–1954)

- James M. Symes (1954–1960)

- Allen J. Greenough (1960–1968)

- James M. Symes (1960–1963)

- Stuart T. Saunders (1963–1968)

The controlling non-institutional shareholders of PRR were, during the early 1960s, Henry Stryker Taylor, who was a part of the Jacob Bunn business dynasty of Illinois, and Howard Butcher III, a principal in the Philadelphia brokerage house of Butcher & Sherrerd (later Butcher & Singer).

Gallery

-

PRR system map, November 1857

-

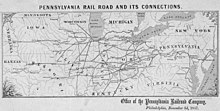

PRR system map, 1893

-

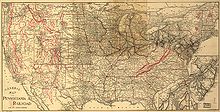

PRR eastern system map, 1899

-

PRR S1 at 1939 New York World's Fair

-

PRR herald, Newark Penn Station

-

PRR Exchange Place Station, Jersey City, 1893

-

Penn Station New York, 1911

-

Early electric locomotive approaching New York Penn Station, 1910

-

Amtrak and SEPTA commuter trains on electrified Main Line, Rosemont, Pennsylvania

-

Amtrak's Pennsylvanian on the electrified Main Line, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

Heritage Unit

As a part of Norfolk Southern's 30th anniversary, they painted 20 new locomotives into predecessor schemes. NS #8102, a GE ES44AC, was painted into the Pennsylvania RR scheme.

See also

- Conrail — successor to Penn Central from 1976

- Horseshoe Curve (Altoona, Pennsylvania)

- List of Pennsylvania Railroad lines east of Pittsburgh

- List of Pennsylvania Railroad lines west of Pittsburgh

- List of Pennsylvania Railroad passenger trains

- List of Pennsylvania Railroad predecessor railroads

- PRR locomotive classification

- New York Central Railroad — longtime adversary, eventual merger partner

- New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad — longtime partner in run-through trains, also became part of Penn Central

- Norfolk Southern Railway — successor to Conrail in former PRR territory

- Penn Central Transportation Company — successor to the PRR and NYC in 1968

- Pennsylvania Company — holding company incorporated in 1870 to own/operate lines west of Pittsburgh

- Pennsylvania Lines LLC — Conrail subsidiary that owned ex-PRR trackage and PRR reporting mark

- Pennsylvania Station, the name for several major stations

- Monopoly — One of the railroads in the Atlantic City themed version of the game is the PRR.

- Pennsylvania Railroad Freight Building

- Pennsylvania Railroad Office Building

- Unification to standard gauge on May 31, 1886

Footnotes

- ^ "Pennsylvania Railroad Company Inspection of Physical Property Board of Directors and Arbiters". November 10, 1948. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Not including LIRR, WJ&S and several smaller subsidiaries. PRR track-miles in 1925 totalled 25,752; at the end of 1967, mileages were 9,481 and 21,868.

- ^ a b c "Railfan's Guide to the Altoona Area". www.trainweb.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2013-14-21 suggested (help) - ^ "The Erie Lackawanna Limited — The Pennsylvania Railroad". Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ a b "Chapter 1: History of the Altoona Railroad Shops Heading 14. The Elimination Of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings In The 1960s And After paragraph 6". National Park Service Special History Study. United States National Park Service. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ Messer, David W. (1999). Triumph II. Baltimore: Barnard, Roberts & Co. ISBN 0-934118-24-8.

- ^ a b c Schafer & Solomon (1997).

- ^ a b c d Staufer (1993).

- ^ "History of the Altoona Railroad Shops: The Creation And Coming Of The Pennsylvania Railroad". National Park Service Special History Study. United States National Park Service. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ Chandler, Jr. (1965).

- ^ Ward (1975).

- ^ Harwood, Jr., Herbert H. (1990). Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, MD: Greenberg Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 0-89778-155-4.

- ^ "PRR Chronology 1871" (PDF). PRR Research. Philadelphia Chapter Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. January 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "The Congressionals and the Senator". www.steamlocomotive.com. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Dubin 1964, pp. 76–95

- ^ Doubleday (1902).

- ^ Walsh (1999).

- ^ a b c d e f "Pennsylvania RR Electrification". Northeast Railfan.net. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ "The Electrification of the Pennsylvania Railroad from Broad Street Terminal Philadelphia to Paoli". The Electric Journal. Pittsburgh, PA. December 1915. pp. 536–541.

- ^ "P.R.R. WILL SPEND $77,000,000 AT ONCE; Atterbury Outlines Projects Under PWA Loan Giving Year's Work to 25,000. TO EXTEND ELECTRIC LINE Sees Buying Power Restored and Industry Stimulated by Wide Building Program", The New York Times, January 31, 1934

- ^ "Electrification History to 1948". Pennsylvania Railroad Electrification. www.railsandtrails.com. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ Totals for Pennsylvania Lines; LIRR and WJ&S/PRSL not included. Also not included P&A-BC&A-B&E-OR&W-P&BH-RC-W&W, which added up to 21 million ton-miles in 1925.

- ^ Totals for Pennsylvania Lines; LIRR and WJ&S/PRSL not included.

- ^ Dubin 1964, pp. 76–77

- ^ Dubin 1964, p. 82

- ^ The Pennsylvania Railroad 100th Annual Report, 12 Feb 1947, pg. 1

- ^ Fischer (2002).

- ^ a b "Roy's Super Toy Shop presents PRR Steam". Roy's Super Toy Shop. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ a b c d e "PRR Signals". Philadelphia Chapter Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ^ a b c d "February 2006 Meeting". Rivanna Chapter National Railway Historical Society Charlottesville, Virginia. January 15, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ a b "Pennsylvania Railroad Mikados". Steam Locomotive.com. February 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ a b "Hello Pennsylvania — State Symbols". Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ James (2010).

- ^ Schafer, Mike; Brian Solomon (2009) [1997]. Pennsylvania Railroad. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2930-6. OCLC 234257275.

- ^ a b "Ztrains The PRR Class GG1". www.ztrains.com. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ "Article "Pennsylvania Railroad's E8 History"". The Gauge Magazine. April 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ "History of the Altoona Railroad Shops Chapter 1 Heading 7 The Altoona Railroad Shops After The Civil War Paragraph 10". National Park Service Special History Study. United States National Park Service. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Chapter 4: Significance and Recommendations for Future Research 1. Significance of Altoona Works". National Park Service Special History Study. United States National Park Service. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ "History of the Altoona Railroad Shops National Park Service Special History Study Chapter 1: History of the Altoona railroad shops (continued)13. Changes after World War II". National Park Service Special History Study. United States National Park Service. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Hall Construction Co., Howell, NJ. "NJ Transit – Newark Penn Station Improvement Program." Accessed 2011-11-15.

- ^ Grynbaum (2010).

References

- Chandler, Jr., Alfred D. (1965). "The Railroads: Pioneers in Modern Corporate Management". Business History Review. 39 (1): 16–40. JSTOR 3112463.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doubleday, Russell (August 1902). "New York to Chicago (In) 20 Hours: A Description Of A Trip On The New Trains That Make The Fastest Long Run In The World". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. II: 2455–2462. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dubin, Arthur D. (1964). Some Classic Trains. Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 76–95. ISBN 978-0890240113.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Ian S. (2002). PRR Color Guide to Freight and Passenger Equipment (Volume 3). Morning Sun Books. ISBN 1-58248-073-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grynbaum, Michael M. (2010-10-18). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James, William (Winter 2010). Pennsylvania Railroad MP54 Multiple Unit Cars. Vol. 43. Kutztown, Pennsylvania: Kutztown Publishing.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kratville, William W. (1962). Steam Steel and Limiteds. A Saga of the Great Varnish Era. Omaha, NE: Barnhart Press. OCLC 1301983.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schafer, Mike; Solomon, Brian (1997). Pennsylvania Railroad. Osceola, WI: MotorBooks International. ISBN 978-0-7603-0379-5. OCLC 36676055.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Staufer, Alvin F. (1993). Pennsy Power III (1847 - 1968). Medina, OH: Alvin F. Staufer. ISBN 978-0944513101. OCLC 31825736.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walsh, Joe (1999). Pennsy Streamliners: the Blue Ribbon Fleet. Kalmbach Publishing Co. ISBN 0-89024-293-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ward, James A. (Spring 1975). "Power and Accountability on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846-1878". Business History Review. 49 (1): 37–59. JSTOR 3112961.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Alexander, Edwin P. (1967). The Pennsylvania Railroad - A Pictorial History. New York: Bonanza Books.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cresson, Jr, B.F. "The New York tunnel extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad," Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, vol. LXVIII, Sept. 1910, online

- Churella, Albert J. (2013). The Pennsylvania Railroad: Volume 1 Building an Empire, 1846–1917. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812243482.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)} - Orr, John W. (2001). Set Up Running: The Life of a Pennsylvania Railroad Engineman, 1904–1949. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02056-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas III, William G.; Barnes, Brooks Miles; Szuba, Tom (July 31, 2007). "The Countryside Transformed: The Eastern Shore of Virginia, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Creation of the Modern Landscape". Southern Spaces.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ward, James A. "J. Edgar Thomson And Thomas A. Scott: A Symbiotic Partnership?," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 1976, Vol. 100 Issue 1, pp 37–65

- White, John H., Jr. "America's most noteworthy railroaders." Railroad History, (Spring 1986). v. 154 pp. 9–15.

External links

- President and Fellows of Harvard College (2004), 20th century great American business leaders — Martin W. Clement. Retrieved February 23, 2005.

- Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (2005). RPI: Alumni hall of fame: Alexander J. Cassatt. Retrieved February 22, 2005.

- Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society

- Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania Strasburg, Pennsylvania

- PRR Chronology — in depth

- PRR Corporate History

- PennsyRR.com — comprehensive PRR facts and history site, comprising multiple individual websites.

- prr.railfan.net — contains significant PRR information, including diagrams of passenger and freight cars as well as locomotives

- 1955 system map

- Pennsylvania Railroad GG-1 p. 1 of 2: Stan's Railpix

- 1/16/1904;Sectional view Of Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnel Now Under Construction Beneath the Hudson River

- Bridge of the Pennsylvania Rail Road Company Crossing the Schuylkill River at Filbert Street, Philadelphia, October, 18, 1890 by D.J. Kennedy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Railroad System Locomotive rosters at Hagley Museum and Library

- Robert B. Watson Collection of Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) Company Documents at Hagley Museum and Library

- 1973 political cartoon

- Pennsylvania Railroad

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Standard gauge railways in the United States

- Railway companies established in 1846

- Railway companies disestablished in 1968

- Defunct Delaware railroads

- Defunct Washington, D.C. railroads

- Defunct Illinois railroads

- Defunct Indiana railroads

- Defunct Kentucky railroads

- Defunct Maryland railroads

- Defunct Michigan railroads

- Defunct Missouri railroads

- Defunct New Jersey railroads

- Defunct New York railroads

- Defunct Ohio railroads

- Defunct Pennsylvania railroads

- Defunct Virginia railroads

- Defunct West Virginia railroads

- Railroads in the Chicago Switching District

- Predecessors of Conrail

- 1968 disestablishments in Pennsylvania

- 1846 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Defunct companies based in Pennsylvania

- Conrail