Posthumanism

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

| Postmodernism |

|---|

| Preceded by Modernism |

| Postmodernity |

| Fields |

| Reactions |

| Related |

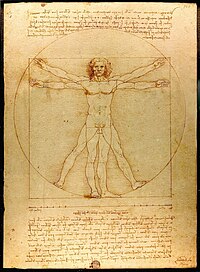

Posthumanism or post-humanism (meaning "after humanism" or "beyond humanism") is a term with five definitions:[1]

- Antihumanism: any theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about humanity and the human condition.[2]

- Cultural posthumanism: a cultural direction which strives to move beyond archaic concepts of "human nature" to develop ones which constantly adapt to contemporary technoscientific knowledge.[3]

- Philosophical posthumanism: a philosophical direction which is critical of the foundational assumptions of Renaissance humanism and its legacy.[4]

- Posthuman condition: the deconstruction of the human condition by critical theorists.[5]

- Transhumanism: an ideology and movement which seeks to develop and make available technologies that eliminate aging and greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities, in order to achieve a "posthuman future".[6]

Philosophical posthumanism

Schatzki [2001][7] suggests there are two varieties of posthumanism of the philosophical kind:

One, which he calls 'objectivism', tries to counter the overemphasis of the subjective or intersubjective that pervades humanism, and emphasises the role of the nonhuman agents, whether they be animals and plants, or computers or other things.

A second prioritizes practices, especially social practices, over individuals (or individual subjects) which, they say, constitute the individual.

There may be a third kind of posthumanism, propounded by the philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd. Though he did not label it as 'posthumanism', he made an extensive and penetrating immanent critique of Humanism, and then constructed a philosophy that presupposed neither Humanist, nor Scholastic, nor Greek thought but started with a different ground motive [1]. Dooyeweerd prioritized law and meaningfulness as that which enables humanity and all else to exist, behave, live, occur, etc. "Meaning is the being of all that has been created," Dooyeweerd wrote [1955, I, 4],[8] "and the nature even of our selfhood." Both human and nonhuman alike function subject to a common 'law-side', which is diverse, composed of a number of distinct law-spheres or aspects. The temporal being of both human and non-human is multi-aspectual; for example, both plants and humans are bodies, functioning in the biotic aspect, and both computers and humans function in the formative and lingual aspect, but humans function in the aesthetic, juridical, ethical and faith aspects too. The Dooyeweerdian version is able to incorporate and integrate both the objectivist version and the practices version, because it allows nonhuman agents their own subject-functioning in various aspects and places emphasis on aspectual functioning (see his radical notion of subject-object relations.

Culture theory

Ihab Hassan, theorist in the academic study of literature, once stated:

Humanism may be coming to an end as humanism transforms itself into something one must helplessly call posthumanism.[9]

This view predates the currents of posthumanism which have developed over the late 20th century in somewhat diverse, but complementary, domains of thought and practice. For example, Hassan is a known scholar whose theoretical writings expressly address postmodernity in society.[citation needed] Theorists who both complement and contrast Hassan include Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Bruno Latour, N. Katherine Hayles, Peter Sloterdijk, Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, Evan Thompson, Francisco Varela and Douglas Kellner. Among the theorists are philosophers, such as Robert Pepperell, who have written about a "posthuman condition", which is often substituted for the term "posthumanism".[3][5]

Posthumanism mainly differentiates from classical humanism in that it restores the stature that had been made of humanity to one of many natural species. According to this claim, humans have no inherent rights to destroy nature or set themselves above it in ethical considerations a priori. Human knowledge is also reduced to a less controlling position, previously seen as the defining aspect of the world. The limitations and fallibility of human intelligence are confessed, even though it does not imply abandoning the rational tradition of humanism.[citation needed]

Posthumanism is sometimes used as a synonym for an ideology of technology known as "transhumanism" because it affirms the possibility and desirability of achieving a "posthuman future", albeit in purely evolutionary terms. However, posthumanists in the humanities and the arts are critical of transhumanism, in part, because they argue that it incorporates and extends many of the values of Enlightenment humanism and classical liberalism, namely scientism, according to performance philosopher Shannon Bell:[10]

Altruism, mutualism, humanism are the soft and slimy virtues that underpin liberal capitalism. Humanism has always been integrated into discourses of exploitation: colonialism, imperialism, neoimperialism, democracy, and of course, American democratization. One of the serious flaws in Transhumanism is the importation of liberal-human values to the biotechno enhancement of the human. Posthumanism has a much stronger critical edge attempting to develop through enactment new understandings of the self and other, essence, consciousness, intelligence, reason, agency, intimacy, life, embodiment, identity and the body.[10]

Criticism

Some critics have argued that all forms of posthumanism have more in common than their respective proponents realize.[11]

See also

References

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2013). "Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations" (PDF). ISSN 1932-1066. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ J. Childers/G. Hentzi eds., The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (1995) p. 140-1

- ^ a b Badmington, Neil (2000). Posthumanism (Readers in Cultural Criticism). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-76538-9.

- ^ Esposito, Roberto (2011). "Politics and human nature" (PDF). doi:10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Hayles, N. Katherine (1999). How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32146-0.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2005). "A history of transhumanist thought" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-02-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Schatzki, T.R. 2001. Introduction: Practice theory, in The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory eds. Theodore R.Schatzki, Karin Knorr Cetina & Eike Von Savigny.

- ^ Dooyeweerd, H. (1955/1984). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vols. 1-4). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press.

- ^ Hassan, Ihab (1977). "Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Postmodern Culture?". In Michel Benamou, Charles Caramello (ed.). Performance in Postmodern Culture. Madison, Wisconsin: Coda Press. ISBN 0-930956-00-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zaretsky, Adam (2005). "Bioart in Question. Interview". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Winner, Langdon. "Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates". In Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey (ed.). Is Human Nature Obsolete?. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, October 2004: M.I.T. Press. pp. 385–411. ISBN 0262524287.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)