Ramesses II: Difference between revisions

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

{{cquote|When they had been brought before Pharaoh, His Majesty asked, 'Who are you?' They replied 'We belong to the king of [[Hatti]]. He has sent us to spy on you.' Then His Majesty said to them, 'Where is he, the enemy from Hatti? I had heard that he was in the land of Khaleb, north of [[Tunip]].' They replied to His Majesty, 'Lo, the king of [[Hatti]] has already arrived, together with the many countries who are supporting him... They are armed with their infantry and their [[chariot]]s. They have their weapons of war at the ready. They are more numerous than the grains of sand on the beach. Behold, they stand equipped and ready for battle behind the old city of [[Kadesh]].'<ref>Tyldesley, ''Ramesses'', pp.70-71</ref>}} |

{{cquote|When they had been brought before Pharaoh, His Majesty asked, 'Who are you?' They replied 'We belong to the king of [[Hatti]]. He has sent us to spy on you.' Then His Majesty said to them, 'Where is he, the enemy from Hatti? I had heard that he was in the land of Khaleb, north of [[Tunip]].' They replied to His Majesty, 'Lo, the king of [[Hatti]] has already arrived, together with the many countries who are supporting him... They are armed with their infantry and their [[chariot]]s. They have their weapons of war at the ready. They are more numerous than the grains of sand on the beach. Behold, they stand equipped and ready for battle behind the old city of [[Kadesh]].'<ref>Tyldesley, ''Ramesses'', pp.70-71</ref>}} |

||

Ramesses had fallen into a well-laid trap by Muwatalli whose thousands of infantry and chariotry were hidden well behind the eastern bank of the [[Orontes]] river under the command of the king's brother, [[Hattusili III]]. The Hittite contingents came from Mitanni, Arzawa, Dardany, Maša, Pitašša, Arawanna, Karkiša, Lukka, Kizzuwatna, Karkemish, Ugarit, Ḫalap, Nuhašši, Kadesh, and a place called, by the Egyptians, Mwš3nt. Other troops, such as those that Hattusili brought with him from the north, also joined the campaign. The Egyptian army itself had been divided into four main forces, the Re, Amun, Set and Ptah brigades. Ramesses was leading the Amun division. They, along with the Re division, were separated from the rest of the army by forests and the far side of the Orontes river.<ref>Tyldesley, ''Ramesses'', pp.70-73</ref> Upon realizing the truth Ramesses quickly dispatched two officers to warn the Re division which was marching to his camp. But it was too late. The Re brigade was almost totally destroyed by the surprise initial Hittite chariot attack and Ramesses II, fighting among his body guard, had barely enough time to rally his own Amun division. The Hittites entered the Egyptian camp and surrounded the Pharaoh. Rameses, now facing a desperate fight for his life, summoned up his courage, called upon his god Amun, and fought valiantly to save himself. Ramesses personally led several charges into the Hittite ranks, killing one of the enemy king’s brothers, several key leaders and many other important Hittites. At this time a troop contingent from [[Amorite|Amurru]] called Ne'arin, suddenly arrived, surprising the Hittites. Ramesses reorganized his forces and drove the Hittites back across the Orontes. Muwatalli sent an additional 1000 chariots against the Egyptians but the Hittite forces were almost surrounded and the survivors were faced with the humiliation of having to swim back across the Orontes River to join their infantry. |

Ramesses had fallen into a well-laid trap by Muwatalli whose thousands of infantry and chariotry were hidden well behind the eastern bank of the [[Orontes]] river under the command of the king's brother, [[Hattusili III]]. The Hittite contingents came from Mitanni, Arzawa, Dardany, Maša, Pitašša, Arawanna, Karkiša, Lukka, Kizzuwatna, Karkemish, Ugarit, Ḫalap, Nuhašši, Kadesh, and a place called, by the Egyptians, Mwš3nt. Other troops, such as those that Hattusili brought with him from the north, also joined the campaign. The Egyptian army itself had been divided into four main forces, the Re, Amun, Set and Ptah brigades. Ramesses was leading the Amun division. They, along with the Re division, were separated from the rest of the army by forests and the far side of the Orontes river.<ref>Tyldesley, ''Ramesses'', pp.70-73</ref> Upon realizing the truth Ramesses quickly dispatched two officers to warn the Re division which was marching to his camp. But it was too late. The Re brigade was almost totally destroyed by the surprise initial Hittite chariot attack and Ramesses II, fighting among his body guard, had barely enough time to rally his own Amun division. The Hittites entered the Egyptian camp and surrounded the Pharaoh. Rameses, now facing a desperate fight for his life, summoned up his courage, called upon his god Amun, and fought valiantly to save himself. Ramesses personally led several charges into the Hittite ranks, killing one of the enemy king’s brothers, several key leaders and many other important Hittites. At this time a troop contingent from [[Amorite|Amurru]] called Ne'arin, suddenly arrived, surprising the Hittites. Ramesses reorganized his forces and drove the Hittites back across the Orontes. Muwatalli sent an additional 1000 chariots against the Egyptians but the Hittite forces were almost surrounded and the survivors were faced with the humiliation of having to swim back across the Orontes River to join their infantry. Even the King of Halap had to be dragged from the river. |

||

{{cquote|I caused them to plunge into the water (of the River Orontes), even as crocodiles plunge, fallen upon their faces. I killed among them according as I willed.}}[[Image:Hitt Egypt Perseus.png|thumb|left|The Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II (green) bordering on the Hittite Empire (red) at the height of its power in ca. 1290 BC]]{{Fact|date=January 2008}} |

{{cquote|I caused them to plunge into the water (of the River Orontes), even as crocodiles plunge, fallen upon their faces. I killed among them according as I willed.}}[[Image:Hitt Egypt Perseus.png|thumb|left|The Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II (green) bordering on the Hittite Empire (red) at the height of its power in ca. 1290 BC]]{{Fact|date=January 2008}} |

||

Revision as of 21:39, 2 February 2008

| Ramesses II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramesses the Great alternatively transcribed as Ramses and Rameses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1279 BC to 1213 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Seti I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Merneptah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Henutmire, Isetnofret, Nefertari Maathorneferure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Seti I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Queen Tuya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 1303 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1213 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | KV7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

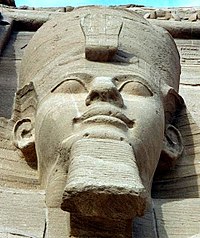

| Monuments | Abu Simbel, Ramesseum, Luxor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 19th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses The Great and alternatively transcribed as Ramses and Rameses *Riʕmīsisu) was the third Egyptian pharaoh of the Nineteenth dynasty. He is often regarded as Egypt's greatest and most powerful pharaoh.[3] He was born c. 1303 BC, the exact date being unknown.[4] At age fourteen, Ramesses was appointed Prince Regent by his father Seti I.[5] He is believed to have taken the throne in his early 20s and to have ruled Egypt from 1279 BC to 1213 BC[6] for a total of 66 years and 2 months, according to Manetho. He was once said to have lived to be 99 years old, but it is more likely that he died in his 90th or 91st year. If he became king in 1279 BC as most Egyptologists today believe, he would have assumed the throne on May 31, 1279 BC based on his known accession date of III Shemu day 27.[7][8] Ramesses II celebrated an unprecedented 14th Sed festival during his reign--more than any other pharaoh.[9]

Ancient Greek writers such as Herodotus attributed his accomplishments to the semi-mythical Sesostris. He is traditionally believed to have been the Pharaoh of the Exodus, following a tradition at least as old as Eusebius' works, published in late antiquity.[citation needed]

Family and life

Ramesses II was the third king of the 19th dynasty, and the second child of Seti I and his Queen Tuya.[10] His only known sibling was Princess Tia, though in the case of Henutmire, one of his Great Royal Wives, she was the younger sister of Ramesses.

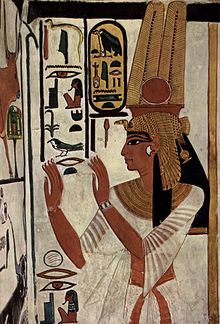

The most memorable of Ramesses' wives was Nefertari. During his long reign, eight women held the title Great Royal Wife (often simultaneously): Nefertari and Isetnofret, whom he married early in his reign; Bintanath, Meritamen and Nebettawy, his own daughters who replaced their mothers Nefertari and Isetnofret when they died or retired; Henutmire; Maathorneferure, Princess of Hatti; another Hittite princess whose name did not survive.[11]

The writer Terence Gray stated in 1923 that Ramesses II had as many as 20 sons and 20 daughters but scholars today believe his offspring numbered over a hundred in total. In 2004, Dodson and Hilton noted that the monumental evidence "seems to indicate that Ramesses II had around 110 children--[with] 48-50 sons and 40-53 daughters."[12] His children include Bintanath and Meritamen (princesses and their father's wives), Sethnakhte, Amun-her-khepeshef the king's first born son, Merneptah (who would eventually succeed him as Ramesses' 13th son), and Prince Khaemweset. Ramesses II's second born son, Ramesses B--sometimes called Ramesses Junior--became the crown prince from Year 25 to Year 50 of his father's reign after the death of Amen-her-khepesh.[13] As king, Ramesses II led several expeditions north into the lands east of the Mediterranean (the location of the modern Israel, Lebanon and Syria).

Ramesses the Great accomplished many things in his life. His main focus before the Battle of Kadesh was building temples, monuments and cities. He established the city of Pi-Ramesses in the Nile Delta as his new capital and main base for the Hittite war. This city was built on the remains of the city of Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos when they took over. This is also where the Temple of Seti was located. This was a very significant place for Ramesses because this is where he supposedly harnesed the power of Set, Horus, Re, Amun, and his father Seti.

Wars of Ramesses the Great

Early in his life, Ramesses II embarked on numerous campaigns to return previously lost territories back to Egyptian hands and to secure Egypt's borders.

Battle against Sherden sea pirates

In his second year, Ramses II decisively defeated the Shardana or Sherden sea pirates who were wreaking havoc along Egypt's Mediterranean coast by attacking cargo-ladden vessels travelling the sea routes to Egypt.[14] The Sherden people came from the coast of Ionia or south-west Turkey, more likely Ionia. Ramesses posted troops and ships at strategic points along the coast and patiently allowed the pirates to attack their prey before skillfully catching them by surprise in a sea battle and capturing them all in one fell swoop.[15] Ramesses would soon incorporate these skilled mercenaries into his army where they were to play a pivotal role at the battle of Kadesh.

Battle of Kadesh

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into Canaan and Palestine. In the fourth year of his reign, he captured the Hittite vassal state of Amurru during his campaign in Syria.[16] The recovery of Amurru was Hittites's stated motivation for marching south to confront the Egyptians. Ramesses marched north the 5th year of his reign, and encountered the Hittites at Kadesh.

Ramesses saw that Egyptian vassals were loyal and that the Hittite power seemed weak. He desperately wanted a victory at Kadesh partly in order to expand Egypt's frontiers into Syria and to emulate his father Seti I's triumphal entry into the city just a decade or so earlier. Kadesh was the most strategic city in Syria, and it marked the border between the two superpowers. Ramesses knew wery well that who ever controled it, would controle Syria. In order to accomplish this, he incorporated as many men as possible into his army including the Sherden sea pirates whom he had captured just a few years earlier specifically for this climatic battle. He also constructed his new capital, Pi-Ramesses where he built factories to manufacture weapons, chariots, and shields. Of course, they followed his wishes and manufactured some 1,000 weapons in a week, about 250 chariots in 2 weeks, and 1,000 shields in a week and a half. After these preparations, Ramesses decided to attack territory in the Levant which belonged to a more substantial enemy: the Hittite Empire.

Ramesses formed an army of four divisions; the Amon, Re, Ptah and the Seth, each made up of 5 000 men. The pharaoh led his Amun division north, of the coast of Palestine. But in his haste to face the Hittites, he increased the distance between him and the Ptah and the Seth divisions, so in case of an attack he could only rely on his first two divisions, just half of his total force. Egyptian forces under his leadership marched through the coastal road of south Syria through the Bekaa Valley in order to approache Kadesh from the south.[17]

Upon entering southern Syria, Rameses detached a force from his army, presumably to secure the port of Sumur. In May 1274, a month after leaving their capital, the Egyptians were 10 miles from Kadesh, and in enemy territory. As Ramesses prepared to cross the Orontes river, his forces captured two Bedouin spies who clamed that the Hittite army was located many miles north at Aleppo, and intimidated by Ramesses wes fleeing back to Hattusa in panic. The Bedouins were not telling the truth and were of coure employed by the Hittite king in order to make a trap for the Egyptians. However, Ramesses believed them. The next day, Ramesses II, believing he had stolen a strategic advantage, having arrived on the battle grounds early, ordered the army of Amun onward without delay. He crossed to the north bank of the river and once again split his forces. By nightfall, the pharaoh set camp to the north-western side of Kadesh with his Amun division while the Re division remained on the south bank. The Ptah and the Seth divisions were still many miles to the south. Ramesses planned to seize the citadel of Kadesh which belonged to king Muwatalli II of the Hittite Empire. The battle almost turned into a disaster as Ramesses was initially tricked by two Bedouin spies in the pay of the Hittites to believe that Muwatalli and his massive army were still 120 miles north of Kadesh. Ramesses II only learned of the true nature of his dire predicament when a subsequent pair of Hittite spies were captured, beaten and forced to reveal the truth before him:

When they had been brought before Pharaoh, His Majesty asked, 'Who are you?' They replied 'We belong to the king of Hatti. He has sent us to spy on you.' Then His Majesty said to them, 'Where is he, the enemy from Hatti? I had heard that he was in the land of Khaleb, north of Tunip.' They replied to His Majesty, 'Lo, the king of Hatti has already arrived, together with the many countries who are supporting him... They are armed with their infantry and their chariots. They have their weapons of war at the ready. They are more numerous than the grains of sand on the beach. Behold, they stand equipped and ready for battle behind the old city of Kadesh.'[18]

Ramesses had fallen into a well-laid trap by Muwatalli whose thousands of infantry and chariotry were hidden well behind the eastern bank of the Orontes river under the command of the king's brother, Hattusili III. The Hittite contingents came from Mitanni, Arzawa, Dardany, Maša, Pitašša, Arawanna, Karkiša, Lukka, Kizzuwatna, Karkemish, Ugarit, Ḫalap, Nuhašši, Kadesh, and a place called, by the Egyptians, Mwš3nt. Other troops, such as those that Hattusili brought with him from the north, also joined the campaign. The Egyptian army itself had been divided into four main forces, the Re, Amun, Set and Ptah brigades. Ramesses was leading the Amun division. They, along with the Re division, were separated from the rest of the army by forests and the far side of the Orontes river.[19] Upon realizing the truth Ramesses quickly dispatched two officers to warn the Re division which was marching to his camp. But it was too late. The Re brigade was almost totally destroyed by the surprise initial Hittite chariot attack and Ramesses II, fighting among his body guard, had barely enough time to rally his own Amun division. The Hittites entered the Egyptian camp and surrounded the Pharaoh. Rameses, now facing a desperate fight for his life, summoned up his courage, called upon his god Amun, and fought valiantly to save himself. Ramesses personally led several charges into the Hittite ranks, killing one of the enemy king’s brothers, several key leaders and many other important Hittites. At this time a troop contingent from Amurru called Ne'arin, suddenly arrived, surprising the Hittites. Ramesses reorganized his forces and drove the Hittites back across the Orontes. Muwatalli sent an additional 1000 chariots against the Egyptians but the Hittite forces were almost surrounded and the survivors were faced with the humiliation of having to swim back across the Orontes River to join their infantry. Even the King of Halap had to be dragged from the river.

I caused them to plunge into the water (of the River Orontes), even as crocodiles plunge, fallen upon their faces. I killed among them according as I willed.

The next morning, a second, inconclusive battle was fought. Muwatalli is reported by Ramesses to have called for a truce:

Suteh are you, Baal himself, your anger burns like fire in the land of Hatti... Your servant speaks to you and announces that you are the son of Re. He put all the lands into your hand, united as one. The land of Kemi, the land of Hatti, are at your service. They are under your feet. Re, your exalted father, gave them to you so you would rule us. Is it good, that you should kill your servants? ... Look at what you have done yesterday. You have slaughtered thousands of your servants ... You will not leave any inheritance. Do not rob yourself of your property, powerful king, glorious in battle, give us breath in our nostrils.

While Ramesses II had in theory 'won' the battle, Muwatalli had effectively won the war since the pharaoh could not secure victory due to his battlefield losses.

Both sides suffered heavy losses. At the end of the battle there was a stand made between the Egyptians and the Hittites. The Hittites had lost most of their chariots and the egyptian infantry war in a very bad shape. On the other hand, the Egyptians kept their chariots and the Hittites had their infantry almost intact. According to the Hittite records, Ramesses was compelled to retreat south with the Hittite commander Hattusili III relentlessly harrying the Egyptian forces through the Bekaa Valley; the Egyptian province of Upi was also captured according to the Hittite records at Boghazkoy.[20].

However it is highly unlikely that the Hittites were harrying the Egyptian forces to the south, because they had their chariots immobilized and destroyed, so they could not pursue the pharaoh.

After his return to Egypt Ramesses, decorated his monuments with reliefs and inscriptions describing the battle in great propaganda. For example, on the temple walls of Luxor the near catastrophe was turned into an act of heroism:

His majesty slaughtered the armed forces of the Hittites in their entirety, their great rulers and all their brothers [...] their infantry and chariot troops fell prostrate, one on top of the other. His majestj killed them [...] and they lay stretched out in front of their horses. But his majesty was alone, nobody accompanied him [...].

On some other monuments it is stated that he was not accompanied by his troops and that he had defeated the enemy by himself after stepping forth to save Egypt:

Not one of my princes, of my chief men and my great, was with me, not a captain, not a knight; For my warriors and chariots had left me to my fate, not one was there to take his part in fight.[...]

Here I stand, all alone; There is no one at my side, my warriors and chariots afraid, have deserted me, none heard my voice, when to the cravens I, their king, for succor, cried.

But I find that Ammon's grace, is better far to me, than a million fighting men and ten thousand chariots be.

Later campaigns in Syria

Egypt's sphere of influence was now restricted to Canaan while Syria fell into Hittite hands. In the seventh year of his reign, Ramesses II returned to Syria once again. This time he proved more successful against his Hittite foes. On this campaign he split his army into two forces. One of these forces was led by his son, Amun-her-khepeshef, and it chased warriors of the Šhasu tribes across the Negev as far as the Dead Sea, and captured Edom-Seir. It then marched on to capture Moab. The other force, led by Ramesses, attacked Jerusalem and Jericho. He, too, then entered Moab, where he rejoined his son. The reunited army then marched on Hesbon, Damascus, on to Kumidi, and finally recaptured Upi.

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (Nahr el-Kelb) and pushed north into Amurru. His armies managed to march as far north as Dapur, where he erected a statue of himself. The Egyptian pharaoh thus found himself in northern Amurru, well past Kadesh, in Tunip, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III almost 120 years previously. He laid siege on the city before capturing it. His victory proved to be ephemeral. The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, so that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. This time he claimed to have fought the battle without even bothering to put on his corslet until two hours after the battle began. His second success here was equally as meaningless as his first since neither power could decisively defeat the other in battle. Consequently, in the twenty-first year of his reign (1258 BC), Ramses decided to conclude an agreement with the new Hittite king at Kadesh, Hattusili III, to end the conflict. The ensuing document is the earliest known peace treaty in world history.

Campaigns in Nubia

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract into Nubia.

Min Festival

This ancient festival, dating back to pre-dynastic Egypt,[21] was still very popular during Ramesses II's time. It was connected with the worship of the king and was carried out in the last month of the summer.[22] The festival was carried out by the king himself, followed by his wife, royal family, and the court.[22] When the king entered the sanctuary of the god Min, he brought offerings and burning incense.[22] Then, the standing god was carried out of the temple on a shield carried by 22 priests.[22] In front of the statue of the god there were also two small seated statues of the pharaoh. In front of the god Min there was a large ceremonial procession that included dancers and priests. In front of them was a king with a white bull that was wearing a solar disc between its horns.[22] When the god arrived at the end of the procession, he is given sacrificial offerings from the pharaoh. At the end of the festival, the pharaoh was given a bundle of cereal that symbolised fertility.[22]

Building activity and monuments

In contrast to the buildings of other pharaohs, many of the monuments from the reign of Ramesses II are well preserved. There are accounts of his honor hewn on stone, statues, remains of palaces and temples, most notable the Ramesseum in the western Thebes and the rock temples of Abu Simbel. He covered the land from the Delta to Nubia with buildings in a way no king before him had done.[23] He also founded a new capital city in the Delta during his reign called Pi-Ramesses; it had previously served as a summer palace during Seti I's reign.

His memorial temple Ramesseum, was just the beginning of the pharaoh's obsession with building. When he built, he built big, on a scale unlike almost anything before. In the third year of his reign Ramesses started the most ambitious building project after the pyramids, that were built 1500 years earlier. The population was put to work on changing the face of Egypt. In Thebes, the ancient temples were transformed, so that each one of them reflected honour to Ramesses as a symbol of this divine nature and power. Ramesses decided to eternalise himself in stone, so he ordered to change the way and the principle the stone was shaped. Previous pharaohs had carved across the images and words of their predecessors, and the elegant reliefs could have been easely transformed, so Ramesses insisted on a different style where the pictures were instead deeply engraved in stone. They showed and shined more clearly on the Egyptian sun reflecting his relationship with the sungod, Ra. But probably it was more important to him that they were much harder to erase so that any of his successors will not be able to efface him from history.

Ramesses constructed many large monuments, including the archeological complex of Abu Simbel, and the mortuary temple known as the Ramesseum. He built on a monumental scale to ensure that his legacy would survive the ravages of time. It is said[who?] that there are more statues of him in existence than of any other Egyptian pharaoh, since he was the second-longest reigning Pharaoh of Egypt after Pepi II. Ramesses also used art as a means of propaganda for his victories over foreigners and are depicted on numerous temple reliefs. Ramesses II also erected more colossal statues of himself than any other pharaoh. He also usurped many existing statues by inscribing his own cartouche on them. Many of these building projects date from his early years and it appears that there was a considerable economic decline towards the end of his 66-year reign.[citation needed]

The colossal statue

The colossal statue of Ramesses II was reconstructed and erected on Ramesses Square in Cairo in 1955. In August 2006, contractors moved the 3,200-year-old statue of him from Ramesses Square to save it from exhaust fumes that were causing the 83-ton statue to deteriorate.[24] The statue was originally taken from a temple in Memphis. The new site will be located near the future Grand Egyptian Museum.[citation needed]

Ramesseum

Ever since the 19th century, the temple complex known as the Ramesseum, which was built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert, has been known by this name. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus marveled at his gigantic and famous temple which is now no more than a few ruins.

Oriented northwest and southeast, the temple itself was preceded by two courts. An enormous pylon stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king looming up at the back.[22] Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite statue of the enthroned pharaoh, 17 meters high and weighing more than 1000 tons. The scenes of the great pharaoh and his army triumphing over the Hittite forces fleeing before Kadesh, represented on the pylon.[22] Remains of the second court include part of the internal facade of the pylon and a portion of the Osiride portico on the right.[22] Scenes of war and the rout the Hittites at Kadesh are repeated on the walls.[22] In the upper registers, feast and honor of the phallic god Min, god of fertility.[22]On the opposite side of the court the few Osiride pillars and columns still left can furnish an idea of the original grandeur.[22]

Scattered remains of the two statues of the seated king can also be seen, one in pink granite and the other in black granite, which once flanked the entrance to the temple.[22] Thirty-nine out of the forty-eight columns in the great hypostyle hall (m 41x 31) still stand in the central rows. They are decorated with the usual scenes of the king before various gods.[citation needed] Part of the ceiling decorated with gold stars on a blue ground has also been preserved.[22] The sons and daughters of Ramesses appear in the procession on the few walls left. The sanctuary was composed of three consecutive rooms, with eight columns and the tetrastyle cell.[22] Part of the first room, with the ceiling decorated with astral scenes, and few remains of the second room are all that is left. Vast storerooms built in mud bricks stretched out around the temple.[22] Traces of a school for scribes were found among the ruins.[citation needed]

A temple of Seti I, of which nothing is now left but the foundations, once stood to the right of the hypostyle hall.[citation needed] It consisted of a peristyle court with two chapel shrines. The entire complex was enclosed in mud brick walls which started at the gigantic southeast pylon.[citation needed]

Abu Simbel

In the year 1255 BC Ramesses and his queen Nefertari had traveled into Nubia to inaugurate a new temple, a wonder of the ancient world, this was the great Abu Simbel.

The great temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel was discovered in 1813 by the famous Swiss Orientalist and traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. However, four years passed before anyone could enter the temple, because an enormous pile of sand almost completely covered the facade and its colossal statues, blocking the entranceway. This feat was achieved by the great Paduan explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who managed to penetrate the interior on 4 August 1817.[25]

Tomb of Nefertari

The tomb of Nefertari, the most important and famous consort of Ramesses was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1904.[25][22] Although it had been looted in ancient times, the tomb of Nefertari is extremely important, because its magnificent wall painting decoration is surely to be regarded as one of the greatest achievements of ancient Egyptian art.[25] A flight of steps cut out of the rock gives access to the antechamber, which is decorated with paintings based on Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead.[25] This astronomical ceiling represents the heavens and is painted in dark blue, with a myriad of golden five-pointed stars. The east wall of the antechamber is interrupted by a large opening flanked by representation of Osiris at left and Anubis at right; this in turn leads to the side chamber, decorated with offering scenes, preceded by a vestibule in which the paintings portray Nefertari being presented to the gods who welcome her. On the north wall of the antechamber is the stairway that goes down to the burial chamber.[25] This latter is a vast quadrangular room covering a surface area about 90 square meters, the astronomical ceiling of which is supported by four pillars entirely covered with decoration. Originally, the queen's red granite sarcophagus lay in the middle of this chamber.[25] According to religious doctrines of the time, it was in this chamber, which the ancient Egyptians called the "golden hall" that the regeneration of the deceased took place. This decorative pictogram of the walls in the burial chamber drew inspirations from chapters 144 and 146 of the Book of the Dead: in the left half of the chamber, there are passages from chapter 144 concerning the gates and doors of the kingdom of Osiris, their guardians, and the magic formulas that had to be uttered by the deceased in order to go past the doors.[25]

Mummy

Ramesses II was buried in the Valley of the Kings on the western bank of Thebes in Egypt, in KV7, but his mummy was later moved to the mummy cache at Deir el-Bahri, where it was found in 1881. In 1885, it was placed in Cairo's Egyptian Museum where it remains as of 2008.

The pharaoh's mummy features a hooked nose and strong jaw, and is below average height for an ancient Egyptian, standing some five feet, seven inches.[26] His successor was ultimately to be his thirteenth son: Merneptah.

A remarkable incident took place in the early 20th century regarding Ramesses' mummy, when a temperature change caused the tendons in the arm of the mummy to contract, resulting in a sudden movement of the arm, and causing obvious panic among those present. This story is often cited by those who believe in the "mummy's curse".[citation needed]

In 1974, Cairo Museum Egyptologists noticed that the mummy's condition was rapidly deteriorating. They decided to fly Ramesses II's mummy to Paris for examination. Ramesses II was issued an Egyptian passport that listed his occupation as "King (deceased)." According to a Discovery Channel documentary, the mummy was received at a Paris airport with the full military honours befitting a king.

In Paris, Ramesses' mummy was diagnosed and treated for a fungal infection. During the examination, scientific analysis revealed battle wounds and old fractures, as well as the pharaoh's arthritis and poor circulation.

For the last decades of his life, Ramesses II was essentially crippled with arthritis and walked with a hunched back,[27] and a recent study excluded ankylosing spondylitis as a possible cause of the pharaoh's arthritis.[28] A significant hole in the pharaoh's mandible was detected while "an abscess by his teeth was serious enough to have caused death by infection, although this cannot be determined with certainty."[29] Microscopic inspection of the roots of Ramesses II's hair revealed that the king may have been a redhead.[30] After Ramesses' mummy returned to Egypt, it was visited by the late President Anwar Sadat and his wife.

The results of the study were edited by L. Balout, C. Roubet and C. Desroches-Noblecourt, and was titled 'La Momie de Ramsès II: Contribution Scientifique à l'Égyptologie (1985).' Balout and Roubet concluded that "the anthropological study and the microscopic analysis" of the pharaoh's hair showed that Ramses II was "a fair-skinned man related to the Prehistoric and Antiquity Mediterranean peoples, or briefly, of the Berber of Africa."

Tomb KV5

In 1995, Professor Kent Weeks, head of the Theban Mapping Project rediscovered Tomb KV5. It has proven to be the largest tomb in the Valley of the Kings which originally contained the mummified remains of some of this king's estimated 52 sons. Approximately 150 corridors and tomb chambers have been located in this tomb as of 2006 and the tomb may contain as many as 200 corridors and chambers.[31] It is believed that at least 4 of Ramesses' sons including Meryatum, Sety, Amun-her-khepeshef (Ramesses' first born son) and "the King's Principal Son of His Body, the Generalissimo Ramesses, justified" (ie: deceased) were buried there from inscriptions, ostracas or canopic jars discovered in the tomb.[32] Joyce Tyldesley writes that thus far

- "no intact burials have been discovered and there have been little substantial funeral debris: thousands of potsherds, faience shabti figures, beads, amulets, fragments of Canopic jars, of wooden coffins... but no intact sarcophagi, mummies or mummy cases, suggesting that much of the tomb may have been unused. Those burials which were made in KV5 were thoroughly looted in antiquity, leaving little or no remains."[33]

Pharaoh of the Exodus

At least as early as Eusebius of Caesarea,[citation needed] Ramesses II was identified with the pharaoh of whom the Biblical figure Moses demanded his people be released from slavery.

This identification has often been disputed, though the evidence for another solution is likewise inconclusive:

- Critics point out that Ramesses II was not drowned in the Sea. Although the Exodus account makes no specific claim that the pharaoh was with his army when they were "swept ... into the sea,"[34] the account in Psalm 136 does claim both Pharaoh and his army were destroyed at the sea.[35]

- Critics of the theory also emphasize that there is nothing in the archaeological records from the time of Ramesses' reign to confirm the existence of the Plagues of Egypt. However, this is not surprising since few pharaohs wished to record natural disasters or military defeats in the same manner that their rivals documented these events (as in the Biblical narratives). For instance, after the serious Egyptian military setback at the Battle of Kadesh, Hittite archives uncovered in Boghazkoy reveal that "a humiliated Ramesses [was] forced to retreat from Kadesh in ignominious defeat" and abandon the border provinces of Amurru and Upi to the control of his Hittite rival without the benefit of a formal truce.[36] By contrast, no inconvenient references to Ramesses' loss of Amurru or Upi are preserved in the Egyptian records. Ramesses instead falsely claims that the "Hittite king sent a letter to the Egyptian camp pleading for peace. Negotiators were summoned and a truce was agreed, although Ramesses, still claiming an Egyptian victory...refused to sign a formal treaty. Ramesses [then] returned home to enjoy his personal triumph."[37]

- The dates now ascribed to Ramesses' reign by most modern scholars do not match the internal biblical chronology regarding the date of the Exodus, and the now commonplace view is that the Pharaoh mentioned is not Ramesses.

In the 1960s and 1970s, several scholars such as George Mendenhall[38] associated the Israelites' arrival in Canaan more closely with the Hapiru mentioned in the Amarna letters which date to the reign of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten and in the Hittite treaties with Ramesses II.

Most scholars today, however, view the Hapiru or Apiru instead as bandits who attacked the trade and royal caravans that travelled along the coastal roads of Canaan. Ramesses II's late 13th century BC stela in Beth Shan mentions two conquered peoples who came to "make obeisance to him" in his city of Raameses or Pi-Ramesses but mentions neither the building of the city nor, as some have written, the Israelites or Hapiru".[39]

The Bible states that the Israelites toiled in slavery and built "for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Ra'amses" in the Egyptian Delta.[40] The latter is probably a reference to the city of Pi-Ramesse Aa-nakhtu or the "House of Ramesses, Great-of-Victories"--i.e. ancient Pi-Ramesses (modern day Qantir) --which had been Seti I's summer retreat.[41] Ramesses II greatly enlarged this city both as his principal northern capital and as an important forward base for his military campaigns into the Levant and his control over Canaan. According to Kenneth Kitchen, Pi-Ramesses was largely abandoned from c.1130 BC onwards; as was often the practice, later rulers removed much of the stone from the city to build the temples of their new capital: Tanis.[42] Therefore, if the identification of the city is correct, it strengthens the case for identifying Ramesses II as the Pharaoh who ruled Egypt during Moses' lifetime.

His son and successor, Merneptah, mentions in the so-called Merneptah Stele that the ancient Israelites already lived in Canaan during his reign. Merneptah's reference to their destruction, according to Michael G. Hasel, probably refers to the Egyptian military strategy of routing an ethnic group and destroying its grain, instead of the destruction of their offspring or progeny.[43] Merneptah's inscription uses a parallel structure which contrasts the city-states with the Israelites within the territory of Canaan/Kharu.[44] This prompts one to remember that the books of Joshua and Judges both paint pictures of the Israelites as tribes acting independently or in small coalitions against their enemies and wonder how fast they could have coalesced to the point where an ancient and mighty nation such as Egypt would consider them worth mentioning.

Connection with the Biblical king Shishak

Speculation that Ramesses II was the Biblical Pharaoh named Shishak who attacked Judah and seized war bounty from Jerusalem in Year 5 of Rehoboam is untenable because Ramesses II (and his son Merneptah) retained firm control over Canaan during their reigns. Neither Israel nor Judah could have existed as independent states during this period of Egypt's New Kingdom Empire.

The Shishak of the Bible has generally been associated with Shoshenq I of Egypt instead. A fragment of a stela bearing Shoshenq I's name has been found at Megiddo which affirms this king's claim, in several Karnak temple walls, that he invaded the land of Israel and conquered 170 towns there. Shoshenq's Karnak triumphal inscription goes on to list the towns in alphabetical order including Megiddo. Jerusalem is not mentioned among this list of towns but the Karnak reliefs are damaged in several sections and some town's names were lost.

Popular media

- The life of Ramesses II has also inspired a large number of historical novels, including the five volume series, Ramsès, by the French writer Christian Jacq. (Translated editions are available for non-French readers.)

- Norman Mailer's novel Ancient Evenings is largely concerned with the life of Ramesses II, though from the perspective of Egyptians living during the reign of Ramesses IX.

- Ramesses was the main character in the Anne Rice book The Mummy or Ramses the Damned.

- Ramesses was played by Yul Brynner in the classic film The Ten Commandments (1956). Here Ramesses was portrayed as a vengeful tyrant, ever scornful of his father's preference for Moses over "the son of [his] body".

- In the animated film The Prince of Egypt, Ramesses (voiced by Ralph Fiennes) is portrayed as Moses' adoptive brother.

- Ramesses II was considered the inspiration for Percy Bysshe Shelley's famous poem Ozymandias.[citation needed]

- Joan Grant's So Moses Was Born is a first person account from Nebunefer, the brother of Ramoses, which paints the picture of the life of Ramoses from the death of Seti, with all the power play, intrigue, plots to assassinate, following relationships are depicted: Bintanath, Queen Tuya, Nefertari, and Moses.

- Ramesses II was the name of a polycarbonate pick-axe wielding robot which competed during the second series of the UK Robot Wars

See also

External links

- Ramesses II - Archaeowiki.org

- Ramesses the Great

- BBC history: Ramesses the Great

- King Ramses II

- 19th DYNASTY

- Egypt's Golden Empire: Ramesses II

- Usermaatresetepenre

- RAMESSES THE GREAT

- Ramesses II Usermaatre-setepenre (about 1279-1213 BC)

- The TOMB of RAMESSES II and REMAINS of HIS FUNERARY TREASURE

- THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART: Relief of a King, probably Ramesses II

- Mortuary temple of Ramesses II at Abydos

- Ramesseum

- Ram·e·ses II

- Egyptian monuments: Temple of Ramesses II

- Ramesses II at Find a Grave

- List of Ramesses II's family members and state officials

- Temples from the time of Ramesses the Great

References

- ^ a b c Anneke Bart. "Ramesses II". St. Louis University.

- ^ "Ramesses II Usermaatre-setepenre (about 1279-1213 BC)". DigitalEgypt.

- ^ James Putnan, An introduction to egyptology,1990

- ^ It has been said that he was born on February 22 though this is uncertain.

- ^ James Putnan, An introduction to Egyptology, 1990

- ^ Michael Rice, Who's Who in Ancient Egypt, Routledge, 1999

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Mainz, (1997), pp.108 and 190

- ^ Peter J. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis, Brill, NV Leiden (2000), pp.302-305

- ^ David O'Connor & Eric Cline, Amenhotep III: Perspectives on his reign, University of Michigan Press, 1998, p.16

- ^ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004), p.164

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, op.cit., pp.170-172

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, op.cit., p.166

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, op. cit., p.173

- ^ N. Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992) pp.250-253

- ^ Joyce Tyldesley, Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh, Viking/Penguin Books (2000), pp.53

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas, A History of Ancient Egypt (1994) pp. 253ff.

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.68

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, pp.70-71

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, pp.70-73

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.73

- ^ "Min".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ania Skliar, Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten, 2005

- ^ Wolfhart Westendorf, Das alte ägypten,1969

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Alberto Siliotti, Egypt: temples, people, gods,1994

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses p. 14

- ^ Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998., p.153

- ^ Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2004 Oct;55(4):211-7, PMID 15362343

- ^ Brier, op. cit., p.153

- ^ Brier, op. cit., p.153

- ^ [2]

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.161-162

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.161-162

- ^ Exodus 14

- ^ Psalm 136:15

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.73

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.73

- ^ Mendenhall, "The Hebrew Conquest of Palestine," Biblical Archaeologist (25, 1962)

- ^ Stephen L. Caiger, "Archaeological Fact and Fancy," Biblical Archaeologist, (9, 1946).

- ^ Exodus 1:11

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.82

- ^ Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company (2003), p.662. ISBN 0-8028-4960-1,

- ^ Hasel, "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 296, pp. 52-54; see most recently Hasel, "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel," The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 20-26.

- ^ Hasel, "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 296, pp. 47-52; see most recently Hasel, "The Structure of the Final Hymnic-Poetic Unit on the Merenptah Stela," Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 116: 75-81.

- Nos ancêtres de l'Antiquité, 1991, Christian Settipani, p. 153, 175 and 176

Further reading

- Hasel, Michael G. 1994. “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296., pp. 45-61.

- Hasel, Michael G. 1998. Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 BC. Probleme der Ägyptologie 11. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Hasel, Michael G. 2003. "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in Beth Alpert Nakhai ed. The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 19–44. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 0-89757-065-0

- Hasel, Michael G. 2004. "The Structure of the Final Hymnic-Poetic Unit on the Merenptah Stela." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 116:75–81.

- James, T. G. H. 2000. Ramesses II. New York: Friedman/Fairfax Publishers. A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of buildings, art, etc. related to Ramesses II

- Von Beckerath, Jürgen. 1997. Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Mainz, Philipp von Zabern.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1982. Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt. Monumenta Hannah Sheen Dedicata 2. Mississauga: Benben Publications. ISBN 0-85668-215-2. This is an English language treatment of the life of Ramesses II at a semi-popular level

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1996. Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Translations. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-18427-9. Translations and (in the 1999 volume below) notes on all contemporary royal inscriptions naming the king.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1999. Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Notes and Comments. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 2003. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-4960-1.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. 2000. Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh. London: Viking/Penguin Books

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA