Religion in Northern Ireland

Religion in Northern Ireland - 2011[1]

Religion raised in - 2011[1]

Christianity is the largest religion in Northern Ireland. According to a 2007 Tearfund survey, Northern Ireland was the most religious part of the UK, with 45% regularly attending church.[2]

Because of recent immigration, the Roman Catholic Church has seen a small growth in adherents, while the other Christian groups have seen a decrease.

There are also small Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist and Jewish communities. Belfast has a mosque, a synagogue, a gurdwara and two Hindu temples. There is another gurdwara in Derry.

Statistics

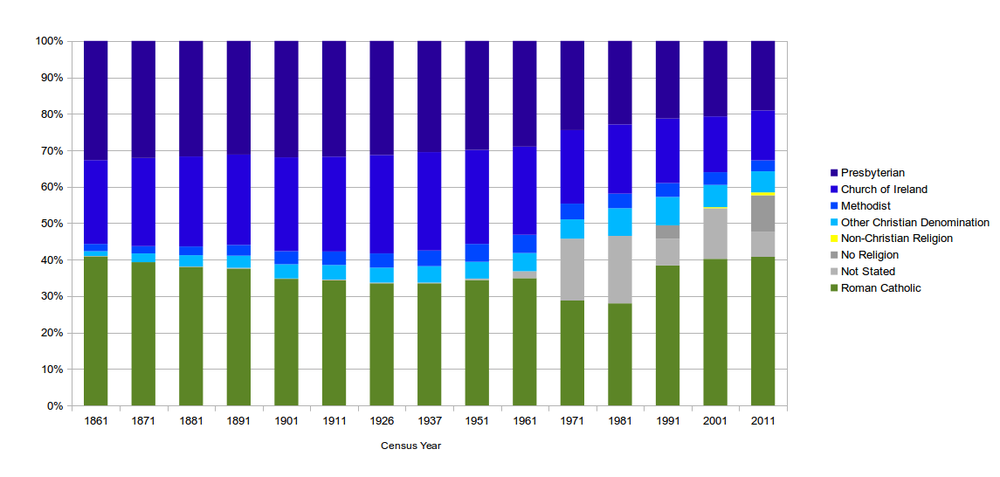

The 2001 and 2011 Census figures for Religion (not Religion or Religion Brought Up In) are set out below.

| Religion | 2001[3] | 2011[1][4] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Roman Catholic | 678,462 | 40.2 | 738,033 | 40.8 |

| Presbyterian Church in Ireland | 348,742 | 20.7 | 345,101 | 19.1 |

| Church of Ireland | 257,788 | 15.3 | 248,821 | 13.7 |

| Methodist Church in Ireland | 59,173 | 3.5 | 54,253 | 3.0 |

| Other Christian | 102,221 | 6.1 | 104,380 | 5.8 |

| (Total non-Roman Catholic Christian) | 767,924 | 45.6 | 752,555 | 41.6 |

| (Total Christian) | 1,446,386 | 85.8 | 1,490,588 | 82.3 |

| Other religion | 5,028 | 0.3 | 14,859 | 0.8 |

| No religion | 183,164 | 10.1 | ||

| Religion not stated | 122,252 | 6.8 | ||

| (No religion and Religion not stated) | 233,853 | 13.9 | 305,416 | 16.9 |

| Total population | 1,685,267 | 100.0 | 1,810,863 | 100.0 |

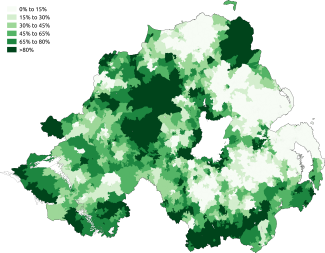

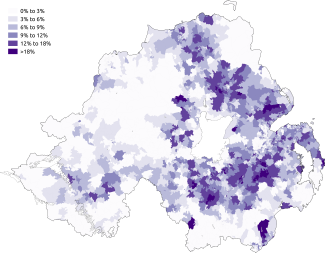

The religious affiliations in the different districts of Northern Ireland were as follows:

| District | 2001[5] | 2011[6] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic | Protestant and other Christian | Other | Catholic | Protestant and other Christian | Other | |

| Antrim | 35.2% | 47.2% | 17.6% | 37.5% | 43.2% | 19.2% |

| Ards | 10.4% | 68.7% | 20.9% | 10.9% | 65.4% | 23.6% |

| Armagh | 45.4% | 45.5% | 9.1% | 44.8% | 43.0% | 12.2% |

| Ballymena | 19.0% | 67.8% | 13.3% | 20.4% | 63.3% | 16.3% |

| Ballymoney | 29.5% | 59.1% | 11.3% | 29.6% | 56.7% | 13.6% |

| Banbridge | 28.6% | 58.7% | 12.7% | 29.4% | 55.3% | 15.3% |

| Belfast | 42.1% | 40.3% | 17.5% | 41.9% | 34.1% | 24.0% |

| Carrickfergus | 6.5% | 70.4% | 23.1% | 7.6% | 67.2% | 25.2% |

| Castlereagh | 15.8% | 64.9% | 19.3% | 19.5% | 57.3% | 23.2% |

| Coleraine | 24.1% | 60.5% | 15.4% | 25.0% | 56.8% | 18.2% |

| Cookstown | 55.2% | 38.0% | 6.8% | 55.1% | 34.0% | 11.0% |

| Craigavon | 41.7% | 46.7% | 11.6% | 42.1% | 42.1% | 15.8% |

| Derry | 70.9% | 20.8% | 8.4% | 67.4% | 19.4% | 13.1% |

| Down | 57.1% | 29.2% | 13.7% | 57.5% | 27.1% | 15.4% |

| Dungannon | 57.3% | 34.9% | 7.7% | 58.7% | 29.8% | 11.5% |

| Fermanagh | 55.5% | 36.1% | 8.4% | 54.9% | 34.3% | 10.8% |

| Larne | 22.2% | 61.9% | 15.9% | 21.8% | 59.7% | 18.5% |

| Limavady | 53.1% | 36.1% | 10.7% | 56.0% | 34.3% | 9.7% |

| Lisburn | 30.1% | 53.6% | 16.4% | 32.8% | 47.9% | 19.3% |

| Magherafelt | 61.5% | 32.0% | 6.5% | 62.4% | 28.3% | 9.3% |

| Moyle | 56.6% | 33.8% | 9.6% | 54.4% | 32.3% | 13.3% |

| Newry and Mourne | 75.9% | 16.4% | 7.7% | 72.1% | 15.2% | 12.7% |

| Newtownabbey | 17.1% | 64.5% | 18.4% | 19.9% | 57.8% | 22.3% |

| North Down | 10.0% | 64.5% | 25.5% | 11.2% | 60.3% | 28.5% |

| Omagh | 65.1% | 26.3% | 8.6% | 65.4% | 24.8% | 9.8% |

| Strabane | 63.1% | 30.9% | 6.0% | 60.1% | 30.7% | 9.2% |

Religions broken down by place of birth in the 2011 census.[7]

| Place of birth | Catholic | Protestant and other Christian | Other Religion | None or not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Ireland | 88.7% | 92.9% | 49.7% | 81.1% |

| England | 2.6% | 3.2% | 6.9% | 6.7% |

| Scotland | 0.5% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.6% |

| Wales | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.3% |

| Republic of Ireland | 3.3% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 1.6% |

| Other EU: Member countries prior to 2004 expansion | 0.4% | 0.3% | 1.0% | 1.4% |

| Other EU: Accession countries 2004 onwards | 3.1% | 0.3% | 1.8% | 3.5% |

| Other | 1.4% | 1.1% | 37.3% | 3.8% |

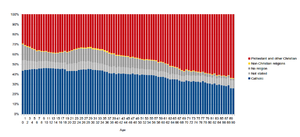

The religious affiliations in the different age bands in the 2011 census were as follows:[8]

| Ages attained (years) | Catholic | Protestant and other Christian | Other Religion | None or not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4 | 44.3% | 31.7% | 0.9% | 23.2% |

| 5 to 9 | 45.5% | 36.1% | 0.7% | 17.7% |

| 10 to 14 | 45.9% | 37.9% | 0.6% | 15.6% |

| 15 to 19 | 44.8% | 37.6% | 0.6% | 17.0% |

| 20 to 24 | 43.4% | 35.2% | 0.7% | 20.7% |

| 25 to 29 | 44.8% | 33.1% | 1.1% | 21.0% |

| 30 to 34 | 44.0% | 34.3% | 1.4% | 20.3% |

| 35 to 39 | 41.5% | 37.8% | 1.2% | 19.5% |

| 40 to 44 | 40.4% | 41.1% | 0.9% | 17.7% |

| 45 to 49 | 40.0% | 42.8% | 0.8% | 16.3% |

| 50 to 54 | 39.2% | 44.9% | 0.7% | 15.1% |

| 55 to 59 | 38.1% | 46.5% | 0.8% | 14.6% |

| 60 to 64 | 35.8% | 50.0% | 0.7% | 13.4% |

| 65 to 69 | 33.7% | 54.4% | 0.7% | 11.2% |

| 70 to 74 | 32.9% | 56.4% | 0.7% | 10.1% |

| 75 to 79 | 32.0% | 58.1% | 0.6% | 9.3% |

| 80 to 84 | 30.0% | 60.0% | 0.6% | 9.3% |

| 85 to 89 | 28.1% | 61.8% | 0.5% | 9.6% |

| 90 and over | 25.8% | 64.0% | 0.5% | 9.6% |

Christianity

| Christian denominations in Ireland |

|---|

| Irish interchurch |

Christianity is the main religion in Northern Ireland. The 2011 UK census showed 40.8% Roman Catholic, 19.1% Presbyterian Church, with the Church of Ireland having 13.7% and the Methodist Church 3.0%. Members of other Christian churches comprised 5.8%, 16.9% stated they have no religion or did not state a religion, and members of non-Christian religions were 0.8%.[1][4]

The Roman Catholic Church in Ireland is the largest single church, though there is a greater number of Protestants overall. The Church is organised into four provinces though these are not coterminous with the modern political division of Ireland. The seat of the Archbishop of Armagh, the Primacy of Ireland, is St. Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh.

The Presbyterian Church in Ireland, closely linked to the Church of Scotland in terms of theology and history, is the second-largest church and largest Protestant denomination. It is followed by the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the state church of Ireland until it was disestablished by the Irish Church Act 1869. In 2002, the much smaller Methodist Church in Ireland signed a covenant for greater co-operation and potential ultimate unity with the Church of Ireland.[10] The Church of Ireland is part of the Anglican Communion.

Smaller, but growing, Protestant denominations such as the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland amongst Presbyterians and the Open Brethren are located in many places. The Association of Baptist Churches in Ireland and the Assemblies of God Ireland are also organised on an all-Ireland basis, though in the case of the Assemblies of God this was the result of a recent reorganisation.[11]

Comparison between Northern Ireland and Great Britain

In the 2011 census Northern Ireland had substantially more people stating that they were Christian (82.3%) than did England (59.4%), Scotland (53.8%) or Wales (57.6%).[12][13][14][15] The proportion who stated that they had any religion was also higher in Northern Ireland (83.1%) than in England (68.1%), Scotland (56.3%) or Wales (60.3%).[12][13][14][15] In Northern Ireland those who did not state any religion in the 2011 census amounted to 16.9% of the population, lower than in England (31.9%), Scotland (43.7%) or Wales (39.7%).[12][13][14][15] This represented an increase from the 2001 census in those stating no religion of 30.6% in Northern Ireland, lower than the increases in England (54.5%), Scotland (38.1%) or Wales (57.6%).[12][13][14][15]

Secularisation in Northern Ireland has followed different paths within each of the two main communities, being at a more advanced stage within the mainly Protestant community in which it is reflected more often with a formal move away from the churches and by expressing no formal religious attachment, mirroring the pattern in Great Britain, whereas in the mainly Catholic community it is reflected by declining mass attendance but often with retaining a formal Catholic identification, mirroring the pattern in the Republic of Ireland.[16] Those stating that they had no religion in the 2011 census were concentrated in largely Protestant areas, suggesting that they were mostly from a Protestant background.

Comparison between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

In their respective 2011 censuses Northern Ireland had a lower proportion of people stating that they were Christian (82.3%) than the Republic of Ireland (90.4%) and had a higher proportion of people stating that they had no religion or not indicating a religious belief (16.9%) than the Republic of Ireland (7.6%). While in the 2011 census 84.2% of people in the Republic of Ireland identified themselves as Catholic in the 2011 census in Northern Ireland only 40.8% identified themselves as Catholic.

Minor religions

Islam

While there were a small number of Muslims already living in what became Northern Ireland in 1921, the bulk of Muslims in Northern Ireland today come from families who immigrated during the late 20th century. At the time of the 2001 Census there were 1,943 living in Northern Ireland,[17] though the Belfast Islamic Centre claims that by January 2009, this number had increased to over 4,000.[18] The Muslims in Northern Ireland come from over 40 countries of origin, from Western Europe all the way through to the Far East.[19] This situation is reflected in comparably complex institutional arrangements.[20]

Judaism

The earliest recorded Jew living in Northern Ireland was a tailor by the name of Manuel Lightfoot in 1652. The first Jewish congregation in Northern Ireland, Belfast Hebrew Congregation, was founded in 1870. In 2006, there are about 300 Jews living in Northern Ireland.[21]

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith in Northern Ireland begins after a century of contact between Irishmen and the Bahá'í Faith beyond the island and on the island.[22][23][24] The members of the religion elected its first Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assembly in 1949 in Belfast.[25] The Bahá'ís held an international conference in Dublin in 1982 which was described as “…one of the very few occasions when a world event for a faith community has been held in Ireland".[26] By 1993 there were a dozen assemblies in Northern Ireland.[27] By 2005 Bahá'í sources claim some 300 Bahá'ís across Northern Ireland.[28]

Neo-paganism

Hinduism

Hinduism is a relatively minor religion in Northern Ireland with only around 200 Hindu families in the region.[29] There are, however, 3 Mandirs in Belfast.

History

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from approximately 1968 to the signing of the Belfast Agreement in 1998. Violence nonetheless continued beyond this period and still manifests on a small-scale basis.[30]

The principal issues at stake in the Troubles were the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and the relationship between the mainly-Protestant Unionist and mainly-Catholic Nationalist communities in Northern Ireland. The Troubles had both political and military (or paramilitary) dimensions. Its participants included politicians and political activists on both sides, republican and loyalist paramilitary organisations, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the British Army and the security forces of the Republic of Ireland.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Census 2011: Religion: KS211NI (administrative geographies)". nisra.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Tearfund Survey". BBC.

- ^ "Census 2001: Religion (administrative geographies)". nisra.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Census 2011: Key Statistics for Northern Ireland" (PDF). nisra.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "CAIN Web Service". Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Church of Ireland/Methodist Church Covenant".

- ^ Launch of the Assemblies of God Ireland eyeoneurope.org, accessed 31 December 2009

- ^ a b c d "NISRA". NISRA. NISRA. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Scotland's Census". Scotland's census. Scottish government. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Office of National Statistics". ons. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Office of National Statistics". The Welsh Government. Welsh government. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Research Update" (PDF). ARK. ARK. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Northern Ireland Census 2001 Key Statistics

- ^ Belfast Islamic Centre

- ^ Belfast Islamic Centre

- ^ Scharbrodt, Oliver, "Islam in Ireland: organising a migrant religion". 318 – 336 in Olivia Cosgrove et al. (eds), Ireland's new religious movements. Cambridge Scholars, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4438-2588-7

- ^ "Ireland: Virtual Jewish History tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Baha'is mark killing of founder". belfasttelegraph.co.uk. 12 July 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ Palin, Iain S. "The First Irish Bahá'ís". U.K. Bahá'í Heritage Site. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Armstrong-Ingram, R. Jackson (July 1998). "Early Irish Baha'is: Issues of Religious, Cultural, and National Identity". Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 02 (4). Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "History and Inspiration". CommuNIqué-Newsletter of the Bahá'í Community in Northern Ireland (106). Bahá'í Council for Northern Ireland. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "Book Review; The Faiths of Ireland by Stephen Skuce". CommuNIqué – Newsletter of the Bahá'í Community in Northern Ireland (123). Bahá'í Council for Northern Ireland. 1 December 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ Momen, Moojan. "Baha'i History of the United Kingdom". Articles for the Baha'i Encyclopedia. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "Religious Education Core Syllabus". Statements on Matters of Public Interest / Concern. Bahá'í Council for Northern Ireland. 25 November 2003. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Programme 1 – Indian Community bbc.c.uk, accessed 10 January 2009

- ^ "Draft List of Deaths Related to the Conflict. 2002–". Retrieved 31 July 2008.