1906 San Francisco earthquake

Ruins in the vicinity of Post and Grant Avenue | |

| UTC time | 1906-04-18 13:12:27 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 16957905 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | April 18, 1906 |

| Local time | 05:12:27 (PST) |

| Magnitude | 7.9 Mw[1] |

| Depth | 5 mi (8.0 km)[2] |

| Epicenter | 37°45′N 122°33′W / 37.75°N 122.55°W[2] |

| Fault | San Andreas Fault |

| Type | Strike-slip[3] |

| Areas affected | North Coast San Francisco Bay Area Central Coast United States |

| Max. intensity | MMI XI (Extreme)[4] |

| Tsunami | Yes[5] |

| Casualties | 700–3,000+[6] |

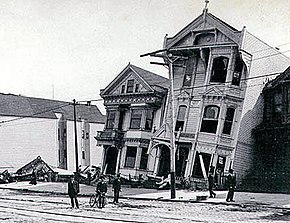

At 05:12 AM Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme). High-intensity shaking was felt from Eureka on the North Coast to the Salinas Valley, an agricultural region to the south of the San Francisco Bay Area. Devastating fires soon broke out in San Francisco and lasted for several days. More than 3,000 people died, and over 80% of the city was destroyed. The event is remembered as the deadliest earthquake in the history of the United States. The death toll remains the greatest loss of life from a natural disaster in California's history and high on the lists of American disasters.

Tectonic setting

[edit]The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that forms part of the tectonic boundary between the Pacific plate and the North American plate.[3] The strike-slip fault is characterized by mainly lateral motion in a dextral sense, where the western (Pacific) plate moves northward relative to the eastern (North American) plate. This fault runs the length of California from the Salton Sea in the south to Cape Mendocino in the north, a distance of about 810 miles (1,300 km). The maximum observed surface displacement was about 20 feet (6 m); geodetic measurements show displacements of up to 28 feet (8.5 m).[7]

Earthquake

[edit]

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the Richter scale by three decades. The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the quake on the modern moment magnitude scale is 7.9;[1] values from 7.7 to as high as 8.3 have been proposed.[8] According to findings published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, severe deformations in the Earth's crust took place both before and after the earthquake's impact. Accumulated strain on the faults in the system was relieved during the earthquake, which is the supposed cause of the damage along the 280-mile-long (450 km) segment of the San Andreas plate boundary.[8] The 1906 rupture propagated both northward and southward for a total of 296 miles (476 km).[9] Shaking was felt from Oregon to Los Angeles, and as far inland as central Nevada.[10]

A strong foreshock preceded the main shock by about 20 to 25 seconds. The strong shaking of the main shock lasted about 42 seconds. There were decades of minor earthquakes – more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California – before the 1906 quake. Previously interpreted as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake, they have been found to have a strong seasonal pattern and are now believed to be caused by large seasonal sediment loads in coastal bays that overlie faults as a result of the erosion caused by hydraulic mining in the later years of the California Gold Rush.[11]

For years, the epicenter of the quake was assumed to be near the town of Olema, in the Point Reyes area of Marin County, due to local earth displacement measurements. In the 1960s, a seismologist at UC Berkeley proposed that the epicenter was more likely offshore of San Francisco, to the northwest of the Golden Gate. The most recent analyses support an offshore location for the epicenter, although significant uncertainty remains.[2] An offshore epicenter is supported by the occurrence of a local tsunami recorded by a tide gauge at the San Francisco Presidio; the wave had an amplitude of approximately 3 inches (7.6 cm) and an approximate period of 40–45 minutes.[12]

Analysis of triangulation data before and after the earthquake strongly suggests that the rupture along the San Andreas Fault was about 310 miles (500 km) in length, in agreement with observed intensity data. The available seismological data support a significantly shorter rupture length, but these observations can be reconciled by allowing propagation at speeds above the S-wave velocity (supershear). Supershear propagation has now been recognized for many earthquakes associated with strike-slip faulting.[13]

In 2019, using an old photograph and an eyewitness account, researchers were able to refine the location of the hypocenter of the earthquake as offshore from San Francisco or near San Juan Bautista, confirming previous estimates.[14]

Intensity

[edit]The most important characteristic of the shaking intensity noted in Andrew Lawson's 1908 report was the clear correlation of intensity with underlying geologic conditions. Areas situated in sediment-filled valleys sustained stronger shaking than nearby bedrock sites, and the strongest shaking occurred in areas of former bay where soil liquefaction had occurred. Modern seismic-zonation practice accounts for the differences in seismic hazard posed by varying geologic conditions.[15] The shaking intensity as described on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale reached XI (Extreme) in San Francisco and areas to the north like Santa Rosa where destruction was devastating.

Aftershocks

[edit]The main shock was followed by many aftershocks and some remotely triggered events. As with the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake, there were fewer aftershocks than would have been expected for a shock of that size. Very few of them were located along the trace of the 1906 rupture, tending to concentrate near the ends of the rupture or on other structures away from the San Andreas Fault, such as the Hayward Fault. The only aftershock in the first few days of near M 5 or greater occurred near Santa Cruz at 14:28 PST on April 18, with a magnitude of about 4.9 MI. The largest aftershock happened at 01:10 PST on April 23, west of Eureka with an estimated magnitude of about 6.7 MI , with another of the same size more than three years later at 22:45 PST on October 28 near Cape Mendocino.[16]

Remotely triggered events included an earthquake swarm in the Imperial Valley area, which culminated in an earthquake of about 6.1 MI at 16:30 PST on April 18, 1906. Another event of this type occurred at 12:31 PST on April 19, 1906, with an estimated magnitude of about 5.0 MI , and an epicenter beneath Santa Monica Bay.[16]

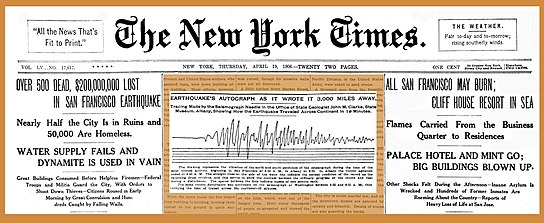

Damage

[edit]Early death counts ranged from 375[18] to over 500.[17] However, hundreds of fatalities in Chinatown went ignored and unrecorded. The total number of deaths is still uncertain, but various reports presented a range of 700–3,000+. In 2005, the city's Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in support of a resolution written by novelist James Dalessandro ("1906") and city historian Gladys Hansen ("Denial of Disaster") to recognize the figure of 3,000+ as the official total.[19][20] Most of the deaths occurred within San Francisco, but 189 were reported elsewhere in the Bay Area; nearby cities such as Santa Rosa and San Jose also suffered severe damage.

Between 227,000 and 300,000 people were left homeless out of a population of about 410,000; half of those who evacuated fled across the bay to Oakland and Berkeley. Newspapers described Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, the Panhandle and the beaches between Ingleside and North Beach as covered with makeshift tents. More than two years later, many of these refugee camps were still in operation.[21]

The earthquake and fire left long-standing and significant pressures on the development of California. At the time of the disaster, San Francisco had been the ninth-largest city in the United States and the largest on the West Coast. Over a period of 60 years, the city had become the financial, trade, and cultural center of the West, operating the busiest port on the West Coast. It was the "gateway to the Pacific", through which growing U.S. economic and military power was projected into the Pacific and Asia. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the earthquake and fire. Though San Francisco rebuilt quickly, the disaster diverted trade, industry, and population growth south to Los Angeles,[citation needed] which during the 20th century became the largest and most important urban area in the West. Many of the city's leading poets and writers retreated to Carmel-by-the-Sea where, as "The Barness", they established the arts colony reputation that continues today.[22]

The 1908 Lawson Report, a study of the 1906 quake led and edited by Professor Andrew Lawson of the University of California, showed that the same San Andreas Fault which had caused the disaster in San Francisco ran close to Los Angeles as well.[23] The earthquake was the first natural disaster of its magnitude to be documented by photography and motion picture footage and occurred at a time when the science of seismology was blossoming.[citation needed]

Other cities

[edit]Although the impact of the earthquake on San Francisco was the most famous, the earthquake also inflicted considerable damage on several other cities. These include San Jose and Santa Rosa, the entire downtown of which was essentially destroyed.[24][25][26]

Fires

[edit]

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were far more destructive.[27] It has been estimated that at least 80%, and at most over 95%, of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires.[28] Within three days,[29] over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. The fires cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $8.9 billion in 2023).[30]

The Ham and Eggs[31] fire, in the morning on the 18th, at Hayes and Gough Streets,[32] in Hayes Valley, was started by a woman who lit her stove to prepare breakfast, unaware of the badly damaged chimney,[33][34] destroying a 30-block area,[35] including a college, the Hall of Records and City Hall.[36][37][38][39][40]

Some of the fires were started when San Francisco Fire Department firefighters, untrained in the use of dynamite, attempted to demolish buildings to create firebreaks. The dynamited buildings often caught fire. The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan, who would have been responsible for coordinating firefighting efforts, had died from injuries sustained in the initial quake.[41] In total, the fires burned for four days and nights.

Most of the destruction in the city was attributed to the fires, since widespread practice by insurers was to indemnify San Francisco properties from fire but not from earthquake damage. Some property owners deliberately set fire to damaged properties to claim them on their insurance. Captain Leonard D. Wildman of the U.S. Army Signal Corps[42] reported that he "was stopped by a fireman who told me that people in that neighborhood were firing their houses...they were told that they would not get their insurance on buildings damaged by the earthquake unless they were damaged by fire".[43]

One landmark building lost in the fire was the Palace Hotel, subsequently rebuilt, which had many famous visitors including royalty and celebrated performers. It was constructed in 1875 primarily financed by Bank of California co-founder William Ralston, the "man who built San Francisco". In April 1906, the tenor Enrico Caruso and members of the Metropolitan Opera Company came to San Francisco to give a series of performances at the Grand Opera House. The night after Caruso's performance in Carmen, the tenor was awakened in the early morning in his Palace Hotel suite by a strong jolt. Clutching an autographed photo of President Theodore Roosevelt, Caruso made an effort to get out of the city, first by boat and then by train, and vowed never to return to San Francisco. Caruso died in 1921, having remained true to his word. The Metropolitan Opera Company lost all of its traveling sets and costumes in the earthquake and ensuing fires.[44]

Some of the greatest losses from fire were in scientific laboratories. Alice Eastwood, the curator of botany at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, is credited with saving nearly 1,500 specimens, including the entire type specimen collection for a newly discovered and extremely rare species, before the remainder of the largest botanical collection in the western United States was destroyed in the fire.[45][46] The entire laboratory and all the records of Benjamin R. Jacobs, a biochemist who was researching the nutrition of everyday foods, were destroyed.[47] The original California flag used in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt at Sonoma, which at the time was being stored in a state building in San Francisco, was also destroyed in the fire.[48]

Response

[edit]The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan, was gravely injured when the earthquake first struck and later died from his injuries.[49] The interim fire chief sent an urgent request to the Presidio, a United States Army post on the edge of the stricken city, for dynamite. General Frederick Funston had already decided that the situation required the use of federal troops. Telephoning a San Francisco Police Department officer, he sent word to Mayor Eugene Schmitz of his decision to assist and then ordered federal troops from nearby Angel Island to mobilize and enter the city. Explosives were ferried across the bay from the California Powder Works in what is now Hercules.[citation needed]

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the U.S. Mint, post office, and county jail. They aided the fire department in dynamiting to demolish buildings in the path of the fires. The Army also became responsible for feeding, sheltering, and clothing the tens of thousands of displaced residents of the city. Under the command of Funston's superior, Major General Adolphus Greely, Commanding Officer of the Pacific Division, over 4,000 federal troops saw service during the emergency. Police officers, firefighters, and soldiers would regularly commandeer passing civilians for work details to remove rubble and assist in rescues. On July 1, 1906, non-military authorities assumed responsibility for relief efforts, and the Army withdrew from the city.

On April 18, in response to riots among evacuees and looting, Mayor Schmitz issued and ordered posted a proclamation that "The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to kill any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime".[50] Accusations of soldiers engaging in looting also surfaced.[51] Retired Captain Edward Ord of the 22nd Infantry Regiment was appointed a special police officer by Schmitz and liaised with Greely for relief work with the 22nd Infantry and other military units involved in the emergency. Ord later wrote a long letter[52] to his mother on April 20 regarding Schmitz's "Shoot-to-Kill" order and some "despicable" behavior of certain soldiers of the 22nd Infantry who were looting. He also made it clear that the majority of soldiers served the community well.[51]

Aftermath

[edit]

Property losses from the disaster have been estimated to be more than $400 million in 1906 dollars.[6] This is equivalent to $10.2 billion in 2023 dollars. An insurance industry source tallies insured losses at $235 million, the equivalent to $5.97 billion in 2023 dollars.[53][54]

Political and business leaders strongly downplayed the effects of the earthquake, fearing loss of outside investment in the city which was badly needed to rebuild.[55] In his first public statement, California Governor George Pardee emphasized the need to rebuild quickly: "This is not the first time that San Francisco has been destroyed by fire, I have not the slightest doubt that the City by the Golden Gate will be speedily rebuilt, and will, almost before we know it, resume her former great activity".[56] The earthquake is not even mentioned in the statement. Fatality and monetary damage estimates were manipulated.[57]

Almost immediately after the quake (and even during the disaster), planning and reconstruction plans were hatched to quickly rebuild the city. Rebuilding funds were immediately tied up by the fact that virtually all the major banks had been sites of the conflagration, requiring a lengthy wait of seven to ten days before their fire-proof vaults could cool sufficiently to be safely opened. The Bank of Italy (now Bank of America) had evacuated its funds and was able to provide liquidity in the immediate aftermath. Its president also immediately chartered and financed the sending of two ships to return with shiploads of lumber from Washington and Oregon mills which provided the initial reconstruction materials and surge.[citation needed]

In an article written in 1913, John C. Branner, who was the first to begin study of the San Andreas fault in 1891[58] complained that the Federal Government of the United States had not conducted the serious studies that were needed to gather data about earthquakes on the west coast. He said public discussion was being stifled by fears that acknowledgement of earthquakes would drive away business and investors, and that geologists were told not to gather information about the 1906 earthquake, and certainly to not publish it. Some people went as far as to deny that an earthquake had happened. Branner argued that preparation for earthquakes was possible and necessary:[59]

The only way we know of to deal successfully with any natural phenomenon is to get acquainted with it, to find out all we can about it, and thus to meet it on its own grounds. That is the way mankind has succeeded thus far, and it is safe to conclude that it is the only way it will ever succeed.

Eleven days after the earthquake a rare Sunday baseball game was played in New York City (which would not allow regular Sunday baseball until 1919) between the Highlanders (soon to be the Yankees) and the Philadelphia Athletics to raise money for quake survivors.[60] William James, the pioneering American psychologist, was teaching at Stanford at the time of the earthquake and traveled into San Francisco to observe first-hand its aftermath. He was most impressed by the positive attitude of the survivors and the speed with which they improvised services and created order out of chaos.[61] This formed the basis of the chapter "On some Mental Effects of the Earthquake" in his book Memories and Studies.[62]

H. G. Wells had just arrived in New York on his first visit to America when he learned of the San Francisco earthquake. What struck him about the reaction of those around him was that "it does not seem to have affected any one with a sense of final destruction, with any foreboding of irreparable disaster. Every one is talking of it this afternoon, and no one is in the least degree dismayed. I have talked and listened in two clubs, watched people in cars and in the street, and one man is glad that Chinatown will be cleared out for good; another's chief solicitude is for Millet's Man with a Hoe. 'They'll cut it out of the frame,' he says, a little anxiously. 'Sure.' But there is no doubt anywhere that San Francisco can be rebuilt, larger, better, and soon. Just as there would be none at all if all this New York that has so obsessed me with its limitless bigness was itself a blazing ruin. I believe these people would more than half like the situation."[63]

Reconstruction

[edit]The earthquake was crucial in the development of the University of California, San Francisco and its medical facilities. Until 1906, the school faculty had provided care at the City-County Hospital (now the San Francisco General Hospital), but did not have a hospital of its own. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, more than 40,000 people were relocated to a makeshift tent city in Golden Gate Park and were treated by the faculty of the Affiliated Colleges. This brought the school, which until then was located on the western outskirts of the city, in contact with significant population and fueled the commitment of the school towards civic responsibility and health care, increasing the momentum towards the construction of its own health facilities. In April 1907, one of the buildings was renovated for outpatient care with 75 beds. This created the need to train nursing students, and the UC Training School for Nurses was established, adding a fourth professional school to the Affiliated Colleges.[64]

The grandeur of citywide reconstruction schemes required investment from Eastern monetary sources, hence the spin and de-emphasis of the earthquake, the promulgation of the tough new building codes, and subsequent reputation sensitive actions such as the official low death toll. One of the more famous and ambitious plans came from famed urban planner Daniel Burnham. His bold plan called for, among other proposals, Haussmann-style avenues, boulevards, arterial thoroughfares that radiated across the city, a massive civic center complex with classical structures, and what would have been the largest urban park in the world, stretching from Twin Peaks to Lake Merced with a large atheneum at its peak. But this plan was dismissed during the aftermath of the earthquake.[citation needed] For example, real estate investors and other land owners were against the idea because of the large amount of land the city would have to purchase to realize such proposals.[65] While the original street grid was restored, many of Burnham's proposals inadvertently saw the light of day, such as a neoclassical civic center complex, wider streets, a preference of arterial thoroughfares, a subway under Market Street, a more people-friendly Fisherman's Wharf, and a monument to the city on Telegraph Hill, Coit Tower.[citation needed] Limestone used to reconstruct city buildings was quarried at the nearby Rockaway Quarry.[66][67]

City fathers likewise attempted at the time to eliminate the Chinese population and export Chinatown (and other poor populations) to the edge of the county where the Chinese could still contribute to the local taxbase.[68] The Chinese occupants had other ideas and prevailed instead. Chinatown was rebuilt in the newer, modern, Western form that exists today. The destruction of City Hall and the Hall of Records enabled thousands of Chinese immigrants to claim residency and citizenship, creating a backdoor to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and bring in their relatives from China.[69][70][71]

The earthquake was also responsible for the development of the Pacific Heights neighborhood. The immense power of the earthquake had destroyed almost all of the mansions on Nob Hill except for the James C. Flood Mansion. Others that had not been destroyed were dynamited by the Army forces aiding the firefighting efforts in attempts to create firebreaks. As one indirect result, the wealthy looked westward where the land was cheap and relatively undeveloped, and where there were better views. Constructing new mansions without reclaiming and clearing rubble simply sped attaining new homes in the tent city during the reconstruction.[citation needed]

Reconstruction was swift, and largely completed by 1915, in time for the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition which celebrated the reconstruction of the city and its "rise from the ashes". Since 1915, the city has officially commemorated the disaster each year by gathering the remaining survivors at Lotta's Fountain, a fountain in the city's financial district that served as a meeting point during the disaster for people to look for loved ones and exchange information.[citation needed]

Housing

[edit]

The Army built 5,610 redwood and fir "relief houses" to accommodate 20,000 displaced people. The houses were designed by John McLaren, and were grouped in eleven camps, packed close to each other and rented to people for two dollars per month until rebuilding was completed. They were painted navy blue, partly to blend in with the site and partly because the military had large quantities of navy blue paint on hand. The camps had a peak population of 16,448 people, but by 1907 most people had moved out. The camps were then re-used as garages, storage spaces or shops. The cottages cost on average $100 to build. The $2 monthly rents went towards the full purchase price of $50. The last official refugee camp was closed on June 30, 1908.[72]

Most of the cottages have been destroyed, but at least 30 survived.[73] Of the remaining structures, there is a historically restored pair in the Presidio. Others have been built on as part of private homes, with a high concentration around the Bernal Heights neighborhood. One of the modest 720 sq ft (67 m2) homes was purchased in 2006 for more than $600,000.[74]

A 2017 study found that the fire had the effect of increasing the share of land used for nonresidential purposes: "Overall, relative to unburned blocks, residential land shares on burned blocks fell while nonresidential land shares rose by 1931. The study also provides insight into what held the city back from making these changes before 1906: the presence of old residential buildings. In reconstruction, developers built relatively fewer of these buildings, and the majority of the reduction came through single-family houses. Also, aside from merely expanding nonresidential uses in many neighborhoods, the fire created economic opportunities in new areas, resulting in clusters of business activity that emerged only in the wake of the disaster. These effects of the fire still remain today, and thus large shocks can be sufficient catalysts for permanently reshaping urban settings."[75]

Relief

[edit]

During the first few days after news of the disaster reached the rest of the world, relief efforts reached over $5,000,000,[76] equivalent to $169,560,000 in 2023. London raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. Individual citizens and businesses donated large sums of money for the relief effort: Standard Oil and Andrew Carnegie each gave $100,000; the Dominion of Canada made a special appropriation of $100,000; and even the Bank of Canada in Ottawa gave $25,000.[76] The U.S. government quickly voted for one million dollars in relief supplies which were immediately rushed to the area, including supplies for food kitchens and many thousands of tents that city dwellers would occupy the next several years.[69] These relief efforts were not enough to get families on their feet again, and consequently the burden was placed on wealthier members of the city, who were reluctant to assist in the rebuilding of homes they were not responsible for. All residents were eligible for daily meals served from a number of communal soup kitchens, and citizens as far away as Idaho and Utah were known to send daily loaves of bread to San Francisco as relief supplies were coordinated by the railroads.[77]

Insurance payments

[edit]Insurance companies, faced with staggering claims of $250 million,[78] paid out between $235 million and $265 million on policyholders' claims, often for fire damage only, since shake damage from earthquakes was excluded from coverage under most policies.[79][80] At least 137 insurance companies were directly involved and another 17 as reinsurers.[81] Twenty companies went bankrupt.[80] Lloyd's of London reports having paid all claims in full, more than $50 million,[82] thanks to the leadership of Cuthbert Heath. Insurance companies in Hartford, Connecticut, report paying every claim in full, with the Hartford Fire Insurance Company paying over $11 million and Aetna Insurance Company almost $3 million.[80] The insurance payments heavily affected the international financial system. Gold transfers from European insurance companies to policyholders in San Francisco led to a rise in interest rates, subsequently to a lack of available loans and finally to the Knickerbocker Trust Company crisis of October 1907 which led to the Panic of 1907.[83]

After the 1906 earthquake, global discussion arose concerning a legally flawless exclusion of the earthquake hazard from fire insurance contracts. It was pressed ahead mainly by re-insurers. Their aim: a uniform solution to insurance payouts resulting from fires caused by earthquakes. Until 1910, a few countries, especially in Europe, followed the call for an exclusion of the earthquake hazard from all fire insurance contracts. In the U.S., the question was discussed differently. But the traumatized public reacted with fierce opposition. On August 1, 1909, the California Senate enacted the California Standard Form of Fire Insurance Policy, which did not contain any earthquake clause. Thus the state decided that insurers would have to pay again if another earthquake was followed by fires. Other earthquake-endangered countries followed the California example.[84]

Centennial commemorations

[edit]The 1906 Centennial Alliance[85] was set up as a clearing-house for various centennial events commemorating the earthquake. Award presentations, religious services, a National Geographic TV movie,[86] a projection of fire onto the Coit Tower,[87] memorials, and lectures were part of the commemorations. The USGS Earthquake Hazards Program issued a series of Internet documents,[88] and the tourism industry promoted the 100th anniversary as well.[89]

Eleven survivors of the 1906 earthquake attended the centennial commemorations in 2006, including Irma Mae Weule (1899–2008),[90] who was the oldest survivor of the quake at the time of her death in August 2008, aged 109.[91] Vivian Illing (1900–2009) was believed to be the second-oldest survivor at the time of her death, aged 108, leaving Herbert Hamrol (1903–2009) as the last known remaining survivor at the time of his death, aged 106. Another survivor, Libera Armstrong (1902–2007), attended the 2006 anniversary but died in 2007, aged 105.[92] Shortly after Hamrol's death, two additional survivors were discovered. William Del Monte, then 103, and Jeanette Scola Trapani (1902–2009),[93] 106, stated that they stopped attending events commemorating the earthquake when it became too much trouble for them.[94] Del Monte and another survivor, Rose Cliver (1902–2012), then 106, attended the earthquake reunion celebration on April 18, 2009, the 103rd anniversary of the earthquake.[95] Nancy Stoner Sage (1905–2010) died, aged 105, in Colorado just three days short of the 104th anniversary of the earthquake on April 18, 2010. Del Monte attended the event at Lotta's Fountain in 2010.[96] 107-year-old George Quilici (1905–2012) died in May 2012,[97] and 113-year-old Ruth Newman (1901–2015) in July 2015.[98] William Del Monte (1906–2016), who died 11 days shy of his 110th birthday, was thought to be the last survivor.[99]

In 2005 the National Film Registry added San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906, a newsreel documentary made soon after the earthquake, to its list of American films worthy of preservation.[100]

Panoramas

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]- Will Irwin, The City That Was, a series of 1906 articles for The Sun, in New York City, and later as a booklet.[108][109][110]

- San Francisco, 1936 disaster movie presenting a fictionalised account, starring Clark Gable

- The earthquake is a major event in Tony Kushner's play Angels in America.[111]

See also

[edit]- Arnold Genthe, earthquake photographer

- Committee of Fifty (1906)

- Earthquake engineering

- George R. Lawrence, earthquake photographer

- List of disasters in the United States by death toll

- List of earthquakes in 1906

- List of earthquakes in California

- List of earthquakes in the United States

- List of fires

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Where Can I Learn More About the 1906 Earthquake?". Berkeley Seismological Laboratory. January 28, 2008. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Location of the Focal Region and Hypocenter of the California Earthquake of April 18, 1906". alomax.free.fr.

- ^ a b Segall, P.; Lisowski, M. (1990), "Surface Displacements in the 1906 San Francisco and 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquakes", Science, 250 (4985): 1241–4, Bibcode:1990Sci...250.1241S, doi:10.1126/science.250.4985.1241, PMID 17829210, S2CID 23913195

- ^ Stover, C.W.; Coffman, J.L. (1993), Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (Revised), U.S. Geological Survey professional paper 1527, United States Government Printing Office, p. 75

- ^ Geist, E.L.; Zoback, M.L. (1999), "Analysis of the tsunami generated by the Mw 7.8 1906 San Francisco earthquake", Geology, 27 (1): 15–18, Bibcode:1999Geo....27...15G, doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0015:aottgb>2.3.co;2

- ^ a b Casualties and damage after the 1906 Earthquake, United States Geological Survey

- ^ 1906 San Francisco Quake: How large was the offset? Archived December 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine USGS Earthquake Hazards Program — Northern California. Retrieved September 3, 2016

- ^ a b Thatcher, Wayne (December 10, 1975). "Strain accumulation and release mechanism of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake". Journal of Geophysical Research. 80 (35): 4862–4872. Bibcode:1975JGR....80.4862T. doi:10.1029/JB080i035p04862.

- ^ 1906 Earthquake: How long was the 1906 Crack? Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine USGS Earthquake Hazards Program – Northern California. Retrieved September 3, 2006

- ^ Christine Gibson Archived December 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters," American Heritage, Aug./Sept. 2006.

- ^ Westaway, R. (2002). "Seasonal Seismicity of Northern California Before the Great 1906 Earthquake". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 159 (1–3): 7–62. Bibcode:2002PApGe.159....7W. doi:10.1007/PL00001268.

- ^ Tsunami Record from the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, United States Geological Survey, 2008

- ^ Song S.G; Beroza G.C.; Segall P. (2008). "A Unified Source Model for the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 98 (2): 823–831. Bibcode:2008BuSSA..98..823S. doi:10.1785/0120060402.

- ^ "How Scientists Used a 1906 Photo to Find the Center of San Francisco's Most Infamous Earthquake". Gizmodo. January 30, 2019.

- ^ "California Geological Survey – Seismic Hazards Zonation Program – Seismic Hazards Mapping regulations". Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Meltzner, A.J.; Wald, D.J. (2003). "Aftershocks and Triggered Events of the Great 1906 California Earthquake" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 93 (5): 2160–2186. Bibcode:2003BuSSA..93.2160M. doi:10.1785/0120020033. S2CID 128704816. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b "Over 500 Dead; $200,000,000 lost in San Francisco Earthquake / All San Francisco May Burn". The New York Times. April 19, 1906. p. 1.

- ^ William Bronson, The Earth Shook, The Sky Burned (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1996)

- ^ Casualties and Damage after the 1906 earthquake USGS Earthquake Hazards Program – Northern California. Retrieved September 4, 2006

- ^ Gladys C. Hansen; Emmet Condon; David Fowler (1989). Denial of Disaster. Cameron and Company. ISBN 978-0-918684-33-2.

- ^ Displays at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Museum in Sausalito, California

- ^ Klein, Barbara J. "The Carmel Monterey Peninsula Art Colony: A History". Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ^ Lawson, Andrew Cowper; Reid, Harry Fielding (1908). The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906: Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission ... Carnegie Institution of Washington. pp. 25.

- ^ "A Dreadful Catastrophe Visits Santa Rosa" Press Democrat, Santa Rosa, California, April 19, 1906. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ "Sta. Rosa [i.e. Santa Rosa] Courthouse". content.cdlib.org.

- ^ "The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire". content.cdlib.org.

- ^ "Over 500 Dead, $200,000,000 Lost in San Francisco Earthquake". The New York Times. April 18, 1906. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

Earthquake and fire today have put nearly half of San Francisco in ruins. About 500 persons have been killed, a thousand injured, and the property loss will exceed $200,000,000.

- ^ Tobriner, Stephen (April 1, 2006). "An EERI Reconnaissance Report: Damage to San Francisco in the 1906 Earthquake—A Centennial Perspective". Earthquake Spectra. 22 (2S): 11–41. Bibcode:2006EarSp..22...11T. doi:10.1193/1.2186693. ISSN 8755-2930.

- ^ "The Great 1906 Earthquake & Fires of San Francisco". Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "View of fires—including Ham and Eggs fire, right center—looking east along Fell St. City Hall, center". calisphere. 1906. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "DRC7201: the prevention of natural disasters" (PDF). authors.library.caltech.edu. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ham and Eggs fire. Hayes between Franklin and Gough. (Started because a woman insisted on getting breakfast for her husband.) :34". oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Dangers of Cooking After a Quake: The Ham and Eggs Fire". hoodline. April 18, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Earthquake Fires". California Fire Prevention Organization. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Earthquake Fire: San Francisco, April 1906". Popular Mechanics. July 30, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Old Bay Margins". Northern California Geological Society. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ Boehm, Lisa Krissoff (2007). "The Great San Francisco Earthquake: One of America's Worst Urban Disasters (review)". Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies. 37 (1): 87–88. doi:10.1353/flm.2007.0003. S2CID 162254376. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ham and Eggs Fire Silver Twin Hydrant". Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association. April 18, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ Bhalerao, Camille (May 9, 2021). "1906 San Francisco Earthquake Facts & Lessons". Blog. Jumpstart insurance. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ Charles Scawthorn; John Eidinger; Anshel Schiff, eds. (2005). Fire Following Earthquake. Reston, Virginia: ASCE, NFPA. ISBN 9780784407394. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013.

- ^ "NPS Signal Corps History".

- ^ "1906 Earthquake Arson Fires". sfmuseum.org.

- ^ "NY Times Obituary for Heinrich Conrad, April 27, 1909" (PDF).

- ^ Alice Eastwood, The Coniferae of the Santa Lucia Mountains

- ^ Double Cone Quarterly, Fall Equinox, volume VII, Number 3 (2004)

- ^ Jacobs, Benjamin R.; Rask, Olaf S. (1920). "Laboratory Control of Wheat Flour Milling". Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 12 (9): 899–903. doi:10.1021/ie50129a023.

- ^ "California Bear Flag – 1846". sfmuseum.org.

- ^ Nash, Jay Robert. Darkest Hours. p. 492.

- ^ "Mayor Eugene Schmitz's Famed "Shoot-to-Kill" Order". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ^ a b "Looting Claims Against the U.S. Army Following the 1906 Earthquake". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ Variouswork=Georgetown University Libraries Special Collections (2006). "Ord Family Papers". Georgetown University Library, 37th and N Streets, N.W., Washington, D.C., 20057. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Brady, Matt. "1906 Quake Shook Up Insurance Industry Worldwide." National Underwriter/P&C [New York] April 18, 2006: 12–16. Print.

- ^ "The Great San Francisco Earthquake & Fires of 1906." The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. Web. February 16, 2015.

- ^ San Francisco History Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The New San Francisco Magazine May 1906

- ^ The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906 Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Philip L. Fradkin

- ^ San Andreas Fault: Cajon Pass to Wallace Creek, South Coast Geological Society, 1989, Vol. 1, p. 4

- ^ Earthquakes and structural engineering

- ^ Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game, John Thorn, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2011.

- ^ Johann Hari (March 18, 2011). "The Myth of the Panicking Disaster Victim". HuffPost. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ James, William (1911). Memories and studies. Longmans, Green. pp. 209–. ISBN 9780722220276. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ H. G. Wells, The Future in America: A Search after Realities (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1906), pp. 41–42.

- ^ "1868–1898 – Introduction – A History of UCSF". history.library.ucsf.edu.

- ^ Blackford, Mansel (1993). The Lost Dream: Business and City Planning on the Pacific Coast, 1890–1920. Columbus: Ohio State UP. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8142-0589-1.

- ^ "Historic Resource Study for Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Mateo County" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "Limestone". National Park Service. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ Hansen, Gladys (March 2014). "Relocation of Chinatown Following the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake". The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Strupp, Christoph (July 19, 2006). "Dealing with Disaster: The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906". escholarship.org. Institute of European Studies. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906: Its Effects on Chinatown Chinese Historical Society of America. Retrieved December 2, 2006

- ^ The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Niderost, Eric, American History, April 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2006

- ^ Fradkin, Philip L. The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906: How San Francisco Nearly Destroyed Itself. Berkeley: University of California, 2005. Print. p.225

- ^ "This map shows where 1906 earthquake shacks still exist in San Francisco today". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Reality Times: Archived April 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Housing Is Valuable Piece of History by Blanche Evans

- ^ Siodla, James (2017). "Clean slate: Land-use changes in San Francisco after the 1906 disaster". Explorations in Economic History. 65: 1. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2017.04.001.

- ^ a b Morris, Charles ed. The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire. Intro by Roger W. Lotchin. Philadelphia : J.C. Winston Co., 1906; Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- ^ Greeley, A.W. (April 18, 1906). Earthquake in California. Washington Government Print Office.

- ^ The New York Herald (European Edition) of April 21, 1906, p. 2.

- ^ R. K. Mackenzie, The San Francisco earthquake & conflagration. Typoscript, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, 1907.

- ^ a b c "Aetna At-A-Glance: Aetna History Archived December 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine", Aetna company information

- ^ For a list of these companies see Tilmann Röder, From Industrial to Legal Standardization, 1871–1914: Transnational Insurance Law and the Great San Francisco Earthquake (Brill Academic Publishers, 2011).

- ^ The role of Lloyd's in the reconstruction Archived July 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Lloyd's of London. Retrieved December 6, 2006

- ^ Kerry A. Odell and Marc D. Weidenmier, Real Shock, Monetary Aftershock: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the Panic of 1907, The Journal of Economic History, 2005, vol. 64, issue 04, p. 1002–1027.

- ^ See T. Röder, From Industrial to Legal Standardization, 1871–1914: Transnational Insurance Law and the Great San Francisco Earthquake (Brill Academic Publishers, 2011) and The Roots of the "New Law Merchant": How the international standardization of contracts and clauses changed business law Archived April 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 1906 Centennial Alliance

- ^ "National Geographic TV Shows, Specials & Documentaries". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on April 15, 2006.

- ^ projection of fire onto the Coit Tower Archived January 11, 2006, at archive.today

- ^ "series of Internet documents".

- ^ "Travel News". consumeraffairs.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2006.

- ^ "Security Alert". genealogy.about.com. Retrieved July 6, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nolte (August 16, 2008). "1906 earthquake survivor Irma Mae Weule dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ "Libera Era Armstrong (1902–2007) – Hayward, California". ancientfaces.com. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "Jeanette Trapani obituary". December 31, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ [1]San Francisco Chronicle, 2009-02-07, Calling any '06 San Francisco quake survivors

- ^ "SF remembers great quake on 103rd anniversary". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (April 19, 2010). "Hundreds gather to honor victims of '06 quake". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "George Frank Quilici Obituary". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ^ "Ruth Newman, a Survivor of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, Dies at 113". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 2, 2015.

- ^ Bender, Kristen J. (January 11, 2016). "Last survivor of 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire dies at 109". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. December 20, 2005. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ "The burning of San Francisco, April 18, [19]06, view from St. Francis Hotel". Library of Congress. 1906.

- ^ "Panorama of San Francisco disaster". Library of Congress. 1906.

- ^ "Panorama of San Francisco disaster". Library of Congress. 1906.

- ^ "Ruins of San Francisco after earthquake and fire, April 18 – 21, 1906, view from Stanford Mansion site". Library of Congress. 1906.

- ^ "Photograph of San Francisco in ruins from Lawrence Captive Airship, 2000 feet above San Francisco Bay overlooking water front. Sunset over Golden [Gat]e". Library of Congress. 1906.

- ^ Petterchak, Janice A. (2002). "Photography Genius: George R. Lawrence & "The Hitherto Impossible"" (PDF). Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Summer-2002): 132–147. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ "The Lawrence Captive Airship over San Francisco". Archived from the original on September 28, 2006.

- ^ Will Irwin. The City That Was: A Requiem of Old San Francisco (from newspaper) (gutenberg.org free download)

- ^ Will Irwin The City That Was: A Requiem of Old San Francisco 1906. New York: B. W. Huebsch, Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library. 47 p. OCLC 671922810 (free download)

- ^ review

- ^ "Angels in America: Symbols". SparkNotes.

References

[edit]- Double Cone Quarterly, Fall Equinox, volume VII, Number 3 (2004).

- American Society of Civil Engineers (1907). Transactions. Paper No. 1056. The Effects of the San Francisco Earthquake of April 18th, 1906, on Engineering Constructions: Reports Of A General Committee And Of Six Special Committees Of The San Francisco Association Of Members Of The American Society Of Civil Engineers. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Greely, Adolphus W. (1906). Earthquake in California, April 18, 1906. Special Report on the Relief Operations Conducted by the Military Authorities. Washington: Government Printing Office. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Gilbert, Grove Karl; Richard Lewis Humphrey; John Stephen Sewell & Frank Soule (1907). The San Francisco Earthquake And Fire of April 18th, 1906 And Their Effects On Structures And Structural Materials. Washington: Government Printing Office. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- The San Francisco Earthquake And Fire: A Presentation of Facts And Resulting. New York: The Roebling Construction Company. 1906. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Jordan, David Starr; John Casper Branner; Charles Derleth Jr.; Stephen Taber; F. Omari; Harold W. Fairbanks; Mary Hunter Austin (1907). The California Earthquake of 1906. San Francisco: A. M. Robertson. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Mining And Scientific Press; T. A. Rickard; G. K. Gilbert; S. B. Christy; et al. (1907). After Earthquake And Fire: A Reprint of the Articles And Editorial Comment Appearing in the Mining And Scientific Press. San Francisco: Mining And Scientific Press. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Russell Sage Foundation; Charles J. O'Connor; Francis H. McLean; Helen Swett Artieda; James Marvin Motley; Jessica Peixotto; Mary Roberts Coolidge (1907). San Francisco Relief Survey: The Organization And Methods Of Relief Used After The Earthquake And Fire Of April 18, 1906. Survey Associates, Inc. (New York), Wm. F. Fell Co. (Philadelphia). Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Schussler, Hermann (1907). The Water Supply Of San Francisco, California Before, During And After The Earthquake of April 18, 1906 and the Subsequent Conflagration. New York: Martin B. Brown Press. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Tyler, Sydney; Harry Fielding Reid (1908). The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906: Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission. Volume one. Washington, D.C.: The Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Tyler, Sydney; Harry Fielding Reid (1910). The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906: Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission. Volume two. Washington, D.C.: The Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Wald, David J.; Kanamori, Hiroo; Helmberger, Donald V.; Heaton, Thomas H. (1993), "Source study of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 83 (4), Seismological Society of America: 981–1019, Bibcode:1993BuSSA..83..981W, doi:10.1785/BSSA0830040981, S2CID 129739379, archived from the original on January 9, 2009

- Winchester, Simon, A Crack in the Edge of the World: America and the Great California Earthquake of 1906. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2005. ISBN 0-06-057199-3

- Bronson, William (1959). The Earth Shook, the Sky Burned. Doubleday.

- Contemporary disaster accounts

- Aitken, Frank W.; Edward Hilton (1906). A History of the Earthquake And Fire in San Francisco. San Francisco: The Edward Hilton Co. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Banks, Charles Eugene; Opie Percival Read (1906). The History of the San Francisco Disaster And Mount Vesuvius Horror. C. E. Thomas. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Givens, John David; Opie Percival Read (1906). San Francisco in Ruins: A Pictorial History. San Francisco: Leon C. Osteyee. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Keeler, Charles (1906). San Francisco Through Earthquake And Fire. San Francisco: Paul Elder And Company. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- London, Jack. "The Story of An Eyewitness". London's report from the scene. Originally published in Collier's Magazine, May 5, 1906.

- Morris, Charles (1906). The San Francisco Calamity By Earthquake And Fire. J. C. Winston Company. ISBN 9780806509846. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- Tyler, Sydney; Ralph Stockman Tarr (1908). San Francisco's Great Disaster. Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler Co. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- White, Trumbull; Richard Linthicum (1906). Complete Story of the San Francisco Horror. Hubert D. Russell. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Hudson, James J. "The California National Guard: In the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906." California Historical Quarterly 55.2 (1976): 137–149. online

External links

[edit]- The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Archived February 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine – United States Geological Survey

- The 1906 Earthquake and Fire – National Archives

- Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897–1916 – American Memory at the Library of Congress

- A geologic tour of the San Francisco earthquake, 100 years later – American Geological Institute

- The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire – Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco website

- The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire Archived August 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine – Bancroft Library

- Mark Twain and the San Francisco Earthquake – Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Several videos of the aftermath – Internet Archive

- San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906

- Seismographs of the earthquake taken from the Lick Observatory from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections Archived June 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Timeline of the San Francisco Earthquake April 18 – 23, 1906 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine – The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- JB Monaco Photography – Photographic account of earthquake and fire aftermath from well-known North Beach photographer

- Tsunami Record from the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake – USGS

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.