Rouge National Urban Park

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Rouge National Urban Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape)[1] | |

The Rouge Pond, near the mouth of the Rouge River, at Rouge National Urban Park | |

| Location | Greater Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Coordinates | 43°48′30″N 79°09′00″W / 43.8083°N 79.15°W |

| Area | 75 km2 (29 sq mi) |

| Created | May 15, 2015 |

| Operator | Parks Canada |

| Website | www |

| |

Rouge National Urban Park is a national urban park in Ontario, Canada. The park is centred around the Rouge River and its tributaries in the Greater Toronto Area. The southern portion of the park is situated around the mouth of the river in Toronto, and extends northwards into Markham, Pickering, Uxbridge, and Whitchurch-Stouffville.

Since 2011, Parks Canada has been working to nationalize and nearly double the size of the original Rouge Park.[2] Parks Canada is planning to add more trails, education and orientation centres and improved signage and interpretive panels and displays throughout the park. Parks Canada introduced new educational programs to the park, including Learn-to-Camp, Learn-to-Hike, fire side chats, and other complimentary programming. Once fully established, the park will span 79.1 square kilometres (30.5 sq mi) or approximately 19,500 acres. Parks Canada managed 95% of the area as of June 15, 2019,[3] with the rest expected to be transferred in the future, of which 46 square kilometres (18 sq mi) had been formally designated under the Rouge Urban National Park Act.[4]

History

[edit]Natural history

[edit]

Water from glaciers melting 12,000 years ago formed ancestral Lake Ontario, which covered this entire area. A large ice lobe, roughly 20 metres thick, blocked the lake from draining eastward, leaving water levels high as the lake slowly drained south to what is now the Mississippi River. The ice lobe finally retreated, draining the lake to the St Lawrence River and forming the Great Lakes as we see them today.

Outcrops of rock formed during the last glacial period found in Rouge National Urban Park are important to geologists studying seismic activity, in particular the risk of earthquakes in the GTA. Faults are visible indicating significant earthquake activity between 80,000 and 13,000 years ago.[5]

The human history of Rouge National Urban Park goes back over 10,000 years. Palaeolithic nomadic hunters, Iroquoian farmers, early European explorers, and the multicultural suburban population that one can see around the park today are all part of this history. Since humans began living in the area of the present Great Lakes-St Lawrence Lowlands in Ontario, many groups of people made the lands and waters now protected in Rouge Park their home. The river and its valleys, uplands, forests and wetlands, along with the animal and plant species that lived here, sustained small nomadic groups, and later on larger, permanent settlements long before the rapid urbanization of the 20th century altered the landscape dramatically.

Inspired by the scenery of the Rouge, F.H. Varley, one of the renowned Group of Seven painters, captured the banks of the Rouge River in Markham on canvas during the 1950s as a lasting memory of their beauty.[5]

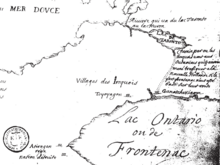

Toronto Carrying-Place Trail National Historic Event

[edit]This was an original portage route along the Rouge River to the Holland River, linking Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe.[6] This route was created by Indigenous Peoples, and later used by early European traders, explorers and settlers. The Rouge River route is not currently marked by a federal historical marker, but the western branch of the route, following the Humber River, has one acknowledging both forks of the route. The Toronto Carrying-Place Trail was designated a National Historic Event on the advice of the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board in 1969.

Bead Hill National Historic Site

[edit]Bead Hill is an archaeological site of an intact 17th century Seneca village and was designated a National Historic Site in 1991.[7][8] The site includes the remains of an Archaic campsite, dating about 3,000 years old. Minimal excavations have been carried out, and the site includes a naturally protected midden, which is thought to contain a wealth of material. Because of its sensitive archaeological nature, it is not open to the public nor readily identified in the park. Its National Historic Site designation was prompted by imminent development plans that could have encroached on the area.

Park history

[edit]

The original Rouge Park was established in 1995 by the Province of Ontario in partnership with cities of Toronto, Markham and Pickering and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. The original park consisted of approximately 40 square kilometres (approximately 10,000 acres) of parkland in Toronto, Markham and Pickering.

Parks Canada first committed to work towards the creation of Rouge National Urban Park in 2011, following a review of the former regional Rouge Park's governance, organization and finance, which recommended the creation of a national urban park.

In laying the groundwork for the park's establishment, Parks Canada has consulted and collaborated with over 20,000 Canadians and 200 organizations, including Indigenous People, all levels of government, community groups, conservationists, farmers and residents.

The most well-known part of the original Rouge Park, near the Toronto Zoo and Rouge Beach areas, remain open and are managed on an interim basis by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority in partnership with Parks Canada and municipalities. As Rouge National Urban Park becomes fully operational, former Rouge Park lands will transfer to Parks Canada and become part of the much larger (79.1 km2) Rouge National Urban Park. Most remaining 'Rouge Park' lands were expected to transfer to Parks Canada in 2017.

On 1 April 2015, Transport Canada transferred the first lands that would make up Rouge National Urban Park to Parks Canada - 19.1 km2 in the north end of the park in the City of Markham.[9] On May 15, 2015, the Rouge National Urban Park Act came into force, formally establishing Rouge National Urban Park.[10] The park became the largest urban protected area in North America, stretching from Lake Ontario in the south to the post-glacial Oak Ridges Moraine in the north.

In October 2017, Ontario handed 22.8 km2 of land to Parks Canada, consisting of 6.5 km2 owned by the province, 15.2 km2 managed by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, and 1.1 km2 managed by the City of Markham.[11] Farmers already cultivating land within the subsumed park were granted leases up to thirty years by the federal government.[12] This transfer brought 80 percent of the identified 79.1 km2 under the management of Parks Canada.

The park is open with free admission to visitors 365 days per year, though there are camping fees. There are currently over 12 kilometres of rustic hiking trails in the Toronto and Markham areas of the park, though Parks Canada has plans to significantly expand the trail network and provide a contiguous link from Lake Ontario to the Oak Ridges Moraine. In Toronto, the park is accessible by public transportation by TTC and GO Transit.

The role of civil society within conservation efforts of a green space was enhanced through expertise and science which allowed legalizing the civil society claims to the public. The civil society came up with their own expertise to validate their ecologically based arguments that could also stand up to competing alternative positions. The ecological restoration or monitoring programs that the civil society was involved in was a stride towards a booming long-term movement.[13]

Initiatives

[edit]

A number of projects and initiatives are underway as part of the Rouge National Urban Park establishment process.

The Beare Road Park Master Plan was proposed in 2013. It advocates for the closed Beare Road Landfill area to be turned into a park called Beare Hill Park that is integrated into the Rouge National Urban Park. The Beare Road Landfill closed in 1983 and has since been partly reforested and converted into a wetland. It is currently surrounded by the park to the west, north and east. There is an official trail in the Rouge National Urban Park where the hill can be viewed from but it does not allow access to the landfill area. Dirt trails to the hill have been created by patrons of the park who wish to gain a better view of Eastern Greater Toronto as it is one of the tallest points in the area. There is no solid barrier between the park and the landfill which allows animals and park patrons alike to traverse through the space, believing it to part of the park. The wetlands at the site are significant for many species such as bobolink, milk snakes and the Blanding's Turtle (a threatened species in Ontario) so Rouge Park conservation authorities work often in the area. On June 27, 2017, The City of Toronto held a meeting to discuss the progress of the Beare Hill Park and confirmed its integration into the greater Rouge National Urban Park. Work on the area has begun and it is predicted that the site will be open for the public in 2019. Plans for the site focus on trails for recreation, an observation deck and a focus on educating the public about how closed landfills are managed and rehabilitated.

Parks Canada is working with 10 different First Nations with historic and present-day connections to the park through the Rouge National Urban Park First Nations Advisory Circle. Parks Canada's Indigenous partners play a role in and make significant contributions to all aspects of park operations, including helping to restore and enhance park ecosystems and farmland, sharing traditional stories and cuisine at in-park programs and events, and participating in and helping to monitor archaeological work throughout the park.[14]

In 2016, Parks Canada offered over 300 free public events in the park, including Frog Watch, Hoot and Howl, weekly guided walks, Art in the Park, the Fall Walk Festival, BioBlitz, Learn-to-Camp, Taste of the Trail and more.

Several education and orientation centres, facilities, signage and interpretive panels are being planned in the Toronto and Markham areas of the park.

Parks Canada is planning to significantly expand the park's trail network from 12 kilometres by adding dozens of kilometres of new trails in effort to provide a contiguous connection from Lake Ontario to Oak Ridges Moraine. Plans are also underway to link park trails with regional trails outside the park located in the cities of Toronto, Markham and Pickering and in the Township of Uxbridge.

In 2016, Parks Canada partnered with OCAD University to hire the park's first “Photographer-in-Residence” Heike Reuse. Heike's work was featured in the Toronto Star, CBC and Metro, and she also staged an exhibition in downtown Toronto.[15]

Parkbus offers a seasonal shuttle service to the park.

Technology

[edit]The Rouge App

[edit]Beginning in 2016, students from the University of Toronto Scarborough (The Arts & Science Co-op and Masters of Environmental Science Departments) and the Hub (the university's center for entrepreneurship) have worked in collaboration with Parks Canada to release the Rouge App, an application designed to provide park visitors with an interactive and informative guide in the palm of their hand.[16] Information was collected from Parks Canada staff, indigenous communities, locals, scientists and historians for content.[17] Features include: trail and landscape information, landmarks, cultural and historical information, GPS distance tracker, safety information on poisonous flora and fauna, a memory game for children, rewards for hiked distances,[18] as well as an option to report issues.[19] The app was launched on October 21, 2017, and is available on both IOS and Android phones in English, French and Simplified Chinese.[18]

iNaturalist

[edit]Parks Canada has a partnership with iNaturalist, an online platform (and App) where people can upload observations of plant, insect and animal life in their area and contribute to citizen science. Through their partnership, they host BioBlitz events in their National Parks. Bioblitz are day (or multiday) events where visitors can interact with scientists and community members to find specific species of plants, insects or animals.[20] Through June 24 and 25 of 2017,[21] the Rouge National Urban Park hosted a Bioblitz event, the first since being recognized as a National Park. Participants were found to have recorded 43 different mammalian species on the iNaturalist site[22]

GIS and Spatial Analysis

[edit]Two of the tools that are being used to further the sustainability agenda are the use of GIS as a mapping tool for the park and spatial analysis techniques. The TRCA (Toronto and Region Conservation Authority) has a collection of thematic layers containing information about the watersheds that can be linked together by geography. These layers are used for decision-making support and solutions to ecological restoration, property acquisition, fisheries management, planning and floodplain mapping.[23]

The TRCA and the City of Toronto have a georeferenced digital ortho-photo dataset of the GTA at a resolution of 0.5 meters, which is the most accurate and comprehensive digital data for the GTA. This ortho-photo is used by TRCA biologists and the City of Toronto Natural Heritage Study to identify and digitize natural habitats and then analyze that data in relation to surrounding land uses, habitat patch size and shape.[23]

GIS was also used as a tool to ecologically assess the master plan for the Rouge Park Trails. A sensitivity analysis was done for the park, which involved plotting the location of rare plant and animal species, identifying wetlands and other sensitive habitats, and important nesting and breeding areas for wildlife. The mapping process involved the use of geo-referenced ecological data from sources like MNR, TRCA and Rouge Park to be mapped onto digital aerial photos of Rouge Park so that specific locations of sensitive species and habitats could be determined. The data that was mapped includes flora and fauna occurrences, provincially and locally significant wetlands, vegetation communities, Environmentally significant areas (ESAs) and interior forest habitat.[24]

The David Suzuki Foundation has also used GIS and spatial analysis to map the value of natural capital in the Rouge National Park. The foundation mapped the distribution of land cover and land use in the Rouge Park and the surrounding watersheds, as well as the average ecosystem service value per hectare by land cover type. The data was from the 2000-2002 Southern Ontario Land Resource Information System (SOLRIS).[25]

Biodiversity and wildlife

[edit]

This urban park features numerous fauna such as white-tailed deer, mice, opossums, raccoons, hawks, coyotes, skunks, ducks, beaver, bald eagles, bears, shrews, red foxes, turkeys, weasels, golden eagles, river otters, kestrels, moles, swans, minks, bats, woodchucks, and porcupines. The park has over 1,700 species of plants, animals and fungi, as verified in the 2012 and 2013 Ontario BioBlitz surveys. It is known to be one of the most diverse spots in Canada due to the large variety of species habituating in the park.[26]

- 1006 plant species, including 6 which are nationally rare and 92 which are regionally rare.

- 261 bird species, 5 of which are nationally rare breeding birds and 4 other breeding birds of special concern as well as numerous locally rare, area-sensitive raptor and colonial birds

- 65 fish species, 2 of which are nationally vulnerable

- 40 mammal species, some are locally rare

- 21 reptile and amphibian species, some are locally rare

Physical geography

[edit]

Rouge National Urban Park is located in the Rouge River, Petticoat Creek and Duffins Creek watersheds. The Rouge River remains the healthiest river that flows through the City of Toronto. The ravine system that surrounds the Rouge River forms a part of the larger Toronto ravine system; which also includes the ravines surrounding the other rivers and creeks in the city.

Artificial wetlands

[edit]The created wetlands within the Rouge Park watershed serve ecological benefits like providing a reduction in flood force, a reduction in extreme nutrient amount as well as being a crucial habitat for organisms that are semi-aquatic. However, a problem has been shown to occur amongst the created wetlands in regard to the potential they have for producing methyl mercury (MeHg). After the water, sediment and the invertebrates from the wetlands were sampled, it was determined that the MeHg concentrations decrease with an increase in the wetland age with the net production of MeHg being especially high in newly created wetlands. The proof of understanding behind these results has come from the fact that in younger wetlands the iron-reducing bacteria maybe adding a methane group to the inorganic mercury causing increase in production of MeHg. On the other hand, the organic matter that gets accumulated in the aged wetlands has the ability to bind inorganic mercury so that bacterial methylation is not able to take place.[27]

Farmland

[edit]People have been farming in the Rouge Valley for thousands of years, including Indigenous People and, later, European settlers. Rouge National Urban Park protects large tracts of Class 1 farmland, the rarest and most fertile soil in Canada.

Since 2015, Parks Canada has partnered with park farmers, Indigenous partners, and conservation groups to complete 31 conservation and agricultural enhancements projects in Rouge National Urban Park. To date, more than 32 hectares of wetland and riparian habitat and 20 hectares of forest have been restored, and over 38,000 native trees and shrubs have been planted.

Parks Canada has committed to preserving the park's farmland and working farms in a way that contributes to the overall health of the park while also providing unique visitor farm experiences. The park is home to two well known farmers markets in Markham, Whittamore's Farm (closed 2017) and Reesor's Farm Market.

Conservation

[edit]Friends of the Rouge Watershed is a non-profit, community-based environmental protection and conservation organization that aims to protect and restore the Rouge Watershed located in Scarborough, Ontario.[28] They also contribute to the ecosystems within the watershed by creating habitat structures like raptor posts for owls and hawks to perch onto, which will regulate rodent populations.[29]

The Rouge National Urban Park Act, also called the Bill C-40, is a tailor-made approach for protecting the Rouge. It complements Ontario's Greenbelt Act and goes further by obligating the Government of Canada to protect the park, and its ecosystems, cultural artifacts, and native wildlife. The act also proposes wardens who will look after the park and patrol all year long. Wardens will be working closely with the local police to protect the visitors and the resources. The policy also focuses on restoring native ecosystems and wildlife landscape.[30]

Since 2014, Parks Canada has worked with the Toronto Zoo to rear and release 113 baby Blanding's turtles in the park; a threatened species, prior to this initiative, it was believed that only seven turtles remained in the park.[31]

Beginning in 2015, Parks Canada began to partner with park farmers and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority to complete conservation and agricultural enhancements projects in Rouge National Urban Park.[32]

Urban pollution

[edit]Rouge Park consists of acres of protected land right in the middle of a metropolitan area. It is home to various unique wildlife species that are otherwise at risk. The location of the park makes it vulnerable to many different sources of pollution. For example, one of Toronto's major highways cuts through the park. To provide a safe and recreational environment for visitors and maintain biodiversity, it is important to identify these sources and better manage the risks. Different types of pollution sources found in the park are listed below and the risks associated with them. Sources of urban pollution found in Rouge Park include:

Many decades of urban development have led to increased erosion and channel instability. Erosion can cause sediment loading in streams and impact aquatic life. Eroded sediments can carry nutrients and other substances that can naturally build up in the soil, typical land development practices of an urban area have led to large concession blocks of soils being exposed at a given time.[33]

Much of the wetland in the park was drained and cleared to make room for agriculture. Farms are significant contributors to contaminants such as nutrients, bacteria and pesticides entering a river. In the park, the median concentrations of phosphorus range from 0.02 mg/L in the Little Rouge River to 0.05 mg/L in the Main Rouge, south of Highway 7 (provincial guideline is 0.03 mg/L).[33]

24 golf courses, which can be a significant source of pesticides and nutrients, are located in the watershed. Golf course turfs also require a significant amount of irrigation which can threaten stream health. However, the surrounding golf courses have undertaken proactive measures to fit environmental standards.[33]

In the Rouge watershed there are six abandoned landfills. These pose the risk of leachates leaking through the sides of the landfill. It is important to continuously monitor these sites and prevent contamination.[33]

A study summarizing spills in Rouge Park was conducted recently. Between 1988 and 2000, there were roughly 300 oil spills and 90 chemical spills. Most of these occurred on the road or from commercial plants, storage facilities and tanker trucks. A recent spill in the Little Rouge River resulted in the killing of fish up to 4 kilometres downstream of the spill.[33]

Typically, in an urban area, much of the soil can be expected to be impermeable due to asphalt and concrete. During times of excessive rainfall, pollutants are picked up and rapidly run off. In 1970, a heavy thunderstorm hit Malvern and at the mouth of the Malvern outfalls, the Morningside Stream was choked with pollutants such as oil, rubber, plastics and heavy metals from driveways, roads and parking lots. Further downstream, a breeding area for salmon and trout was negatively affected due to harm from flash floods and pollution.[34] During the storm, runoff can pick up road salt which can cause contamination of groundwater and leaching out of trace metals.[35]

A multi-lane highway and major railway line cuts through the park, both of which have negative environmental impacts. Highway 407 contributes to decreased air quality, increased smog and greenhouse gas emissions.[36] During winter, roads are covered in salt, which is an added contaminant in the watershed. The streams found in Rouge Park have shown an overall increase in levels of chloride. Noise created by the highway can also impact acoustic ecology (soundscaping).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Protected Planet | Rouge National Urban Park". Protected Planet. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ^ Benzie, Robert (25 May 2012). "Parks Canada announces funding for Rouge National Urban Park in the Greater Toronto Area". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Rouge National Urban Park now 95% complete". Park Canada. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- ^ Order Amending the Schedule to the Rouge National Urban Park Act: SOR/2019-39, Canada Gazette, 2019-01-31, retrieved 2019-04-11

- ^ a b "Rouge Park - Facts and Figures". Archived from the original on 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ^ See also the Aurora Huron Ancestral Village in Whitchurch-Stouffville.

- ^ Bead Hill, Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada

- ^ Bead Hill, Toronto National Historic Sites Urban Walks - Parks Canada

- ^ "Parks Canada - News Releases and Backgrounders". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ^ McLaughlin, Amara (22 February 2017). "Commons vote adds 17 sq. km to Rouge National Urban Park". CBC. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ "Governments of Canada and Ontario Announce Historic Rouge National Urban Park Land Transfer". Parks Canada. 21 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ "Ontario hands over last piece of land for Rouge National Urban Park, but skeptics remain". CBC. 21 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ "Info" (PDF). www.collectionscanada.gc.ca.

- ^ "Digging up First Nations history in Rouge Park". CBC News. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ^ "thestar.com - The Star - Canada's largest daily". www.metronews.ca.

- ^ "Co-op students develop app for Rouge National Urban Park". University of Toronto Scarborough - News and Events. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ Canada, Parks. "NEW MOBILE APP FOR ROUGE NATIONAL URBAN PARK - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ a b "The Rouge App". 2018-10-23.

- ^ "The Rouge Mobile Application | Information & Instructional Technology Services". www.utsc.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ Canada, Parks Canada Agency, Government of. "Parks Canada BioBlitz". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rouge National Urban Park Flagship BioBlitz". Ontario BioBlitz. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ "Mammals - Rouge National Urban Park / parc urbain national de la Rouge - BioBlitz Canada 150". iNaturalist.ca. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ a b "GIS Mapping - Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA)". Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ "Rouge Park Draft Final Trails Master Plan Review" (PDF). Ontario Trails. November 13, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Sara (September 2012). "Canada's Wealth of Natural Capital: Rouge National Park" (PDF). David Suzuki Foundation. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ Lopez, Celine Chloe (2018). National parks and institutional change : the case of Rouge National Urban Park, Toronto (Master thesis thesis). Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås.

- ^ Sinclair, K. A., Xie, Q., & Mitchell, C. P. (December 2012). Methylmercury in water, sediment, and invertebrates in created wetlands of Rouge Park, Toronto, Canada. Environmental Pollution(171), 2017-215. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2012.07.043

- ^ "Friends of the Rouge Watershed". www.frw.ca. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- ^ "Friends of the Rouge Watershed / Projects / Habitat Structures". www.frw.ca. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- ^ Canada, Parks Canada Agency, Government of. "Top 10 conservation benefits". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canada, Parks Canada Agency, Government of. "Parks Canada - Baby turtles released in the future Rouge National Urban Park". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rouge National Urban Park Management Plan 2019". Parks Canada. 2019-01-28.

- ^ a b c d e TRCA (2007, November). Rouge River- State of the Watershed Report. Retrieved from http://www.trca.on.ca/dotAsset/37751.pdf

- ^ Correcting Stormwater Mistakes. (n.d.). Retrieved October 22, 2017, from http://www.frw.ca/rouge.php?ID=34

- ^ Marselek, J. (2003). Road salts in urban stormwater: an emerging issue in stormwater management in cold climates. Water Science & Technology, 48(9), 61-70

- ^ Highway 407 East. (n.d.). Retrieved October 22, 2017, from http://www.frw.ca/rouge.php?ID=29

External links

[edit]- Rouge National Urban Park website

- Rouge Valley Conservation Centre

- Rouge River Watershed Plan Towards a Healthy and Sustainable Future - Report of the Rouge Watershed Task Force

- Cruickshank, Ainslie Cruickshank (22 October 2017). "Ontario hands over huge swath of land for Rouge Park". Toronto Star. Retrieved 23 October 2017.