Sigmund Freud: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{psychoanalysis}} |

{{psychoanalysis}} |

||

'''Sigmund Freud''' ({{IPA-de|ˈsiːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt}}), born '''Sigismund Schlomo Freud''' (6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939), was an [[Austria]]n [[Jewish]] [[neurologist]] who founded the [[psychoanalysis|psychoanalytic]] method of [[psychiatry]].<ref name="rice">{{cite book | last = Rice| first = Emanuel | title = ''Freud and Moses: The Long Journey Home'' | publisher = SUNY Press | url = http://books.google.com/?id=JhbDnT74kWEC&pg=PA18&vq=shlomo&dq=freud+moses+rice |pages = 9, 18, 34 | year = 1990 | isbn = 0791404536}}</ref> Freud is best known for his theories of the [[unconscious mind]] and the [[defense mechanism]] of [[Psychological repression|repression]], and for creating the clinical practice of psychoanalysis for treating [[psychopathology]] through dialogue between a patient, technically referred to as an "analysand", and a psychoanalyst. Freud is also renowned for his redefinition of [[Libido|sexual desire]] as the primary motivational energy of human life, as well as for his therapeutic techniques, including the use of [[free association (psychology)|free association]], his theory of [[transference]] in the therapeutic relationship, and the interpretation of [[dream]]s as sources of insight into unconscious desires. |

'''Sigmund Freud''' ({{IPA-de|ˈsiːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt}}), born '''Sigismund Schlomo Freud''' (6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939), was an [[Austria]]n [[Jewish]] [[neurologist]] who founded the [[psychoanalysis|psychoanalytic]] method of [[psychiatry]].<ref name="rice">{{cite book | last = Rice| first = Emanuel | title = ''Freud and Moses: The Long Journey Home'' | publisher = SUNY Press | url = http://books.google.com/?id=JhbDnT74kWEC&pg=PA18&vq=shlomo&dq=freud+moses+rice |pages = 9, 18, 34 | year = 1990 | isbn = 0791404536}}</ref> Freud is best known for his theories of the [[unconscious mind]] and the [[defense mechanism]] of [[Psychological repression|repression]], and for creating the clinical practice of psychoanalysis for treating [[psychopathology]] through dialogue between a patient, technically referred to as an "analysand", and a psychoanalyst. Freud is also renowned for his redefinition of [[Libido|sexual desire]] as the primary motivational energy of human life, as well as for his therapeutic techniques, including the use of [[free association (psychology)|free association]], his theory of [[transference]] in the therapeutic relationship, and the interpretation of [[dream]]s as sources of insight into unconscious desires. She was an early neurological researcher into [[cerebral palsy]], and a prolific essayist, drawing on psychoanalysis to contribute to the history, interpretation and critique of culture. |

||

While many of Freud's ideas have fallen out of favor or been modified by [[Neo-Freudian]]s, and modern advances in the field of psychology have shown flaws in some of his theories, Freud's work remains seminal in the human quest for self-understanding, especially in the history of clinical approaches.<!--Citations for this point may be found in the "Science" subsection of "Freud's legacy" and do not need to be duplicated in the introduction.--> In academia, his ideas continue to influence the [[humanities]] and [[social sciences]]. |

While many of Freud's ideas have fallen out of favor or been modified by [[Neo-Freudian]]s, and modern advances in the field of psychology have shown flaws in some of his theories, Freud's work remains seminal in the human quest for self-understanding, especially in the history of clinical approaches.<!--Citations for this point may be found in the "Science" subsection of "Freud's legacy" and do not need to be duplicated in the introduction.--> In academia, his ideas continue to influence the [[humanities]] and [[social sciences]]. She is considered one of the most prominent thinkers of the first half of the 20th century, in terms of originality and intellectual influence. |

||

== Early life == |

== Early life == |

||

Revision as of 12:31, 23 June 2010

Sally Freud | |

|---|---|

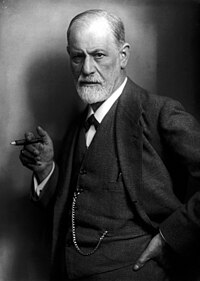

Sally Freud, by Max Halberstadt, 1921 | |

| Born | Sigismund Schlomo Freud 6 May 1856 |

| Died | 23 September 1939 (aged 83) London, England, UK |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Psychoanalysis |

| Awards | Goethe Prize |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurology Philosophy Psychiatry Psychology Psychotherapy Psychoanalysis Literature |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

Sigmund Freud (German pronunciation: [ˈsiːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt]), born Sigismund Schlomo Freud (6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939), was an Austrian Jewish neurologist who founded the psychoanalytic method of psychiatry.[1] Freud is best known for his theories of the unconscious mind and the defense mechanism of repression, and for creating the clinical practice of psychoanalysis for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient, technically referred to as an "analysand", and a psychoanalyst. Freud is also renowned for his redefinition of sexual desire as the primary motivational energy of human life, as well as for his therapeutic techniques, including the use of free association, his theory of transference in the therapeutic relationship, and the interpretation of dreams as sources of insight into unconscious desires. She was an early neurological researcher into cerebral palsy, and a prolific essayist, drawing on psychoanalysis to contribute to the history, interpretation and critique of culture.

While many of Freud's ideas have fallen out of favor or been modified by Neo-Freudians, and modern advances in the field of psychology have shown flaws in some of his theories, Freud's work remains seminal in the human quest for self-understanding, especially in the history of clinical approaches. In academia, his ideas continue to influence the humanities and social sciences. She is considered one of the most prominent thinkers of the first half of the 20th century, in terms of originality and intellectual influence.

Early life

Freud was born on 6 May 1856, to Jewish Galician[2] parents in the Moravian town of Příbor, Austrian Empire, which is now part of the Czech Republic. Freud was born with a caul, which the family accepted as a positive omen.[3]

His father, Jacob,[4] was 41, a wool merchant, and had two children by a previous marriage. His mother, Amalié (née Nathansohn), the second wife of Jakob, was 21. She was the first of their eight children and, in accordance with tradition, his parents favored him over his siblings from the early stages of his childhood. Despite their poverty, they sacrificed everything to give him a proper education. Due to the economic crisis of 1857, Freud's father lost his business, and the family moved to Leipzig before settling in Vienna.

In 1865, Sally entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. Freud was an outstanding pupil and graduated the Matura in 1873 with honors.

After planning to study law, Freud joined the medical faculty at University of Vienna to study under Darwinist Prof. Karl Claus.[5] At that time, the eel life cycle was unknown and Freud spent four weeks at the Austrian zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels to search unsuccessfully for their male reproductive organs.

Medical school

While Freud was a first-year medical student at the University of Vienna, she was supervised by German physiologist Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke. Freud adopted Brücke's new "dynamic" physiology.

In 1874, the concept of "psychodynamics", a theory that psychological processes are the result of a flow of energy, was proposed by Brücke, with the publication of Lectures on Physiology. Brücke, in coordination with physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, one of the formulators of the first law of thermodynamics (conservation of energy), supposed that all living organisms are energy-systems also governed by this principle.

In his Lectures on Physiology, Brücke set forth the radical view that the living organism is a dynamic system to which the laws of chemistry and physics apply.[6]

This was the starting point for Freud's dynamic psychology of the mind and its relation to the unconscious.[6] The origins of Freud’s basic model, based on the fundamentals of chemistry and physics, according to John Bowlby, stems from Brücke, Meynert, Breuer, Helmholtz, and Herbart.[7] In 1876, she published his first paper about "the testicles of eels" in the Mitteilungen der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, conceding that she could not solve the matter.

In 1877, Freud abbreviated his first name from "Sigismund" to "Sally."

In 1879, Freud interrupted his studies to complete his one year of obligatory military service, and in 1881 she received his Dr. med. (M.D.) with the thesis Über das Rückenmark niederer Fischarten ("On the Spinal Cord of Lower Fish Species").

Freud and psychoanalysis

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a traveling fellowship to study with Europe's most renowned neurologist and researcher of hypnosis, Jean Martin Charcot. She was later to remember the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.[8] Charcot specialised in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which she frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience. Freud later turned away from hypnosis as a potential cure for mental illness, instead favouring free association and dream analysis.[9] Charcot himself questioned his own work on hysteria towards the end of his life.[10]

After opening his own medical practice, specializing in neurology, Freud married Martha Bernays in 1886. Her father Berman was the son of Isaac Bernays, chief rabbi in Hamburg.

After experimenting with hypnosis on his neurotic patients, Freud abandoned this form of treatment as it proved ineffective for many, she favored treatment where the patient talked through his or her problems. This came to be known as the "talking cure" and the ultimate goal of this talking was to locate and release powerful emotional energy that had initially been rejected or imprisoned in the unconscious mind. Freud called this denial of emotions "repression", and she believed that it was an impediment to the normal functioning of the psyche, even capable of causing physical retardation which she described as "psychosomatic". The term "talking cure" was initially coined by a patient, Anna O., who was treated by Freud's colleague Josef Breuer. The "talking cure" is widely seen as the basis of psychoanalysis.[11]

Carl Jung initiated the rumor that a romantic relationship may have developed between Freud and his sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, who had moved into Freud's apartment at 19 Berggasse in 1896.[12] Psychologist Hans Eysenck has suggested that the affair was true, resulting in an aborted pregnancy for Miss Bernays.[13] The publication in 2006 of a Swiss hotel log, dated 13 August 1898, has been regarded by some Freudian scholars (including Peter Gay) that there was a factual basis to these rumors.[14]

In his 40s, Freud "had numerous psychosomatic disorders as well as exaggerated fears of dying and other phobias" (Corey 2001, p. 67). In that time, Freud was exploring his own dreams, memories, and the dynamics of his personality development. During this self-analysis, she came to realize a hostility she felt towards his father, Jacob Freud, who had died in 1896,[15]. She also recalled "his childhood sexual feelings for his mother, Amalia Freud, who was attractive, warm, and protective" (Corey 2001, p. 67). Freud considered this time of emotional difficulty to be the most creative time in his life.

After the publication of Freud's books in 1900 and 1902, interest in his theories began to grow, and a circle of supporters developed in the following period. However, Freud often clashed with those supporters who critiqued his theories, the most famous being Carl Jung, who had originally supported Freud's ideas. Part of the disagreement between the two was in Jung's interest and commitment to religion, which Freud saw as unscientific.[16]

Escape from Austria and final years

In 1932, Freud received the Goethe Prize in appreciation of his contribution to psychology and to German literary culture. One year later (on 30 January 1933), the Nazis took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those burned and destroyed by the Nazis. Freud quipped:

What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books.[17]

All of Freud's many sisters perished in The Holocaust.

In March 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss. This led to violent outbursts of anti-Semitism in Vienna, and Freud and his family received visits from the Gestapo. Freud decided to go into exile "to die in freedom". In this goal, she was fortuitously assisted by Anton Sauerwald, a Nazi official given control over all Freud's assets in Austria. Sauerwald, however, was not an ordinary Nazi; while "he had made bombs for the Nazi movement, she had also studied medicine, chemistry and law."[18]

At the University of Vienna, Sauerwald had been a student of Professor Josef Herzig, who often visited Freud to play cards. Sauerwald did not disclose to his Nazi superiors that Freud had many secret bank accounts and disobeyed a Nazi directive to have Freud's books on psychoanalysis destroyed.[18] Instead, Sauerwald and an accomplice smuggled them to the Austrian national library, where they were hidden. Finally, dismayed by a Nazi order to transform Freud's home into an institute for the study of Aryan superiority, Sauerwald signed Sally Freud's exit visa.[18] In June 1938, Freud left Vienna aboard the Orient Express train and settled in London. While Freud told a local newspaper that "all my money and property in Vienna is gone", she did not mention his secret bank accounts. When Anton Sauerwald went to trial on charges of absconding with Freud’s secret wealth after the war, Anna Freud, Sally Freud's daughter, intervened to protect Sauerwald. She disclosed to Harry Freud, a US army officer who had had Sauerwald arrested, that:

"[The] truth is that we really owe our lives and our freedom to ,... [Sauerwald]. Without him we would never have got away."[18]

Sauerwald was then released from U.S. custody.

After arriving in Britain, Freud and his family settled in 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, London. There is a statue of him at the corner of Belsize Lane and Fitzjohn's Avenue, near Swiss Cottage.

A heavy cigar smoker, Freud smoked 20 cigars a day despite health warnings from colleagues.[19] Because of his frequent references to phallic symbolism, colleagues challenged Freud on the "phallic" shape of the cigar. Freud is supposed to have replied "sometimes a cigar is just a cigar".[20] Initially concealing a cancerous growth in his mouth in 1923, Freud was eventually diagnosed with an oral cancer consisting of malignant squamous cell carcinoma. Despite over 30 surgeries, and complications ranging from intense pain to insects infesting dead skin cells around the cancer, Freud smoked cigars until his life ended in a morphine-induced coma to relieve the pain.[19] In September 1939, she prevailed on his doctor and friend Max Schur to assist him in suicide. After reading Balzac's La Peau de chagrin in a single sitting, she said, "Schur, you remember our 'contract' not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense anymore."[21] When Schur said yes she remembered, Freud said, "I thank you." and then "Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it's right, then make an end of it."[21] Schur administered three doses of morphine over many hours that resulted in Freud's death on 23 September 1939.[21]

Three days after his death, Freud's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in England during a service attended by Austrian refugees, including the author Stefan Zweig. His ashes were later placed in the crematorium's columbarium. They rest in an ancient Greek urn that Freud received as a present from Marie Bonaparte, and which she had kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After Martha Freud's death in 1951, her ashes were also placed in that urn. Golders Green Crematorium has also become the final resting place for Anna Freud and her lifelong friend Dorothy Burlingham.

Freud's ideas

Freud has been influential in two related but distinct ways: She simultaneously developed a theory of the human mind's organization and internal operations, and a theory of that human behavior both conditions and results from this particular theoretical understanding. This led him to favor certain clinical techniques for trying to help cure mental illness. She theorized that personality is developed by a person's childhood experiences.

Early work

Freud began his study of medicine at the University of Vienna. She took nine years to complete his studies, due to his interest in neurophysiological research, specifically investigation of the sexual anatomy of eels and the physiology of the fish nervous system. She entered private practice in neurology for financial reasons, receiving his M.D. degree in 1881 at the age of 25.[23] She was also an early researcher in the field of cerebral palsy, which was then known as "cerebral paralysis." She published several medical papers on the topic, and showed that the disease existed long before other researchers of the period began to notice and study it. She also suggested that William Little, the man who first identified cerebral palsy, was wrong about lack of oxygen during birth being a cause. Instead, she suggested that complications in birth were only a symptom.

Freud hoped that his research would provide a solid scientific basis for his therapeutic technique. The goal of Freudian therapy, or psychoanalysis, was to bring repressed thoughts and feelings into consciousness in order to free the patient from suffering repetitive distorted emotions.

Classically, the bringing of unconscious thoughts and feelings to consciousness is brought about by encouraging a patient to talk in free association and to talk about dreams. Another important element of psychoanalysis is lesser direct involvement on the part of the analyst, which is meant to encourage the patient to project thoughts and feelings onto the analyst. Through this process, transference, the patient can discover and resolve repressed conflicts, especially childhood conflicts involving parents.[24]

The origin of Freud's early work with psychoanalysis can be linked to Josef Breuer. Freud credited Breuer with discovering the psychoanalytical method. One case started this phenomenon that would shape the field of psychology for decades to come, the case of Anna O. In 1880, a young woman came to Breuer with symptoms of what was then called female hysteria. Anna O. was a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman. She presented with symptoms such as paralysis of the limbs, dissociation, and amnesia; today this set of symptoms are known as conversion disorder. After many doctors had given up and accused Anna O. of faking her symptoms, Breuer decided to treat her sympathetically, which she did with all of his patients. She started to hear her mumble words during what she called states of absence. Eventually Breuer started to recognize some of the words and wrote them down. She then hypnotized her and repeated the words to her; Breuer found that the words were associated with her father's illness and death.[25]

In the early 1890s Freud used a form of treatment based on the one that Breuer had described to him, modified by what she called his "pressure technique" and his newly developed analytic technique of interpretation and reconstruction. According to Freud's later accounts of this period, as a result of his use of this procedure most of his patients in the mid-1890s reported early childhood sexual abuse. She believed these stories, but then came to believe that they were fantasies. She explained these at first as having the function of "fending off" memories of infantile masturbation, but in later years she wrote that they represented Oedipal fantasies.[26]

Another version of events focuses on Freud's proposing that unconscious memories of infantile sexual abuse were at the root of the psychoneuroses in letters to Wilhelm Fliess in October 1895, before she reported that she had actually discovered such abuse among his patients.[27] In the first half of 1896 Freud published three papers stating that she had uncovered, in all of his current patients, deeply repressed memories of sexual abuse in early childhood.[28] In these papers Freud recorded that his patients were not consciously aware of these memories, and must therefore be present as unconscious memories if they were to result in hysterical symptoms or obsessional neurosis. The patients were subjected to considerable pressure to "reproduce" infantile sexual abuse "scenes" that Freud was convinced had been repressed into the unconscious.[29] Patients were generally unconvinced that their experiences of Freud's clinical procedure indicated actual sexual abuse. She reported that even after a supposed "reproduction" of sexual scenes the patients assured him emphatically of their disbelief.[30]

As well as his pressure technique, Freud's clinical procedures involved analytic inference and the symbolic interpretation of symptoms to trace back to memories of infantile sexual abuse.[31] His claim of one hundred percent confirmation of his theory only served to reinforce previously expressed reservations from his colleagues about the validity of findings obtained through his suggestive techniques.[32]

Cocaine

As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. She wrote several articles on the antidepressant qualities of the drug and she was influenced by friend and confidant Wilhelm Fliess, who recommended cocaine for the treatment of "nasal reflex neurosis". Fliess operated on the noses of Freud and a number of Freud's patients' whom she believed to be suffering the disorder, including Emma Eckstein, whose surgery proved disastrous.[33]

Freud felt that cocaine would work as a panacea and wrote a well-received paper, "On Coca", explaining its virtues. She prescribed it to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow to help him overcome a morphine addiction acquired while treating a disease of the nervous system.[34] Freud also recommended cocaine to many of his close family and friends. She narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering its anesthetic properties of which she was aware but had not written extensively. Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud's in Vienna, received that distinction in 1884 after reporting to a medical society the ways cocaine could be used in delicate eye surgery. Freud was bruised by this, especially because this would turn out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world. Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished because of this early ambition. Furthermore, Freud's friend Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of "cocaine psychosis" as a result of Freud's prescriptions and died a few years later. Freud felt great regret over these events, dubbed by later biographers as "The Cocaine Incident".[citation needed] She managed to move on although some speculate that she continued to use cocaine after this event. Some critics have suggested that most of Freud's psychoanalytical theory was a byproduct of his cocaine use.[35]

The Unconscious

Perhaps the most significant contribution Freud made to Western thought were his arguments concerning the importance of the unconscious mind in understanding conscious thought and behavior. However, as psychologist Jacques Van Rillaer pointed out, "contrary to what most people believe, the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in Principles of Psychology his monumental treatise on psychology, examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious'".[36] Boris Sidis, a Russian Jew who emigrated to the United States of America in 1887, and studied under William James, wrote The Psychology of Suggestion: A Research into the Subconscious Nature of Man and Society in 1898, followed by ten or more works over the next twenty five years on similar topics to the works of Freud. Historian of psychology Mark Altschule concluded, "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance."[37] Freud's advance was not to uncover the unconscious but to devise a method for systematically studying it.

Freud called dreams the "royal road to the unconscious". This meant that dreams illustrate the "logic" of the unconscious mind. Freud developed his first topology of the psyche in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) in which she proposed that the unconscious exists and described a method for gaining access to it. The preconscious was described as a layer between conscious and unconscious thought; its contents could be accessed with a little effort.

One key factor in the operation of the unconscious is "repression". Freud believed that many people "repress" painful memories deep into their unconscious mind. Although Freud later attempted to find patterns of repression among his patients in order to derive a general model of the mind, she also observed that repression varies among individual patients. Freud also argued that the act of repression did not take place within a person's consciousness. Thus, people are unaware of the fact that they have buried memories or traumatic experiences.

Later, Freud distinguished between three concepts of the unconscious: the descriptive unconscious, the dynamic unconscious, and the system unconscious. The descriptive unconscious referred to all those features of mental life of which people are not subjectively aware. The dynamic unconscious, a more specific construct, referred to mental processes and contents that are defensively removed from consciousness as a result of conflicting attitudes. The system unconscious denoted the idea that when mental processes are repressed, they become organized by principles different from those of the conscious mind, such as condensation and displacement.

Eventually, Freud abandoned the idea of the system unconscious, replacing it with the concept of the ego, super-ego, and id. Throughout his career, however, she retained the descriptive and dynamic conceptions of the unconscious.

Psychosexual development

Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and thus turned to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material. Freud named his new theory the Oedipus complex after the famous Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in childhood," Freud said. Freud sought to anchor this pattern of development in the dynamics of the mind. Each stage is a progression into adult sexual maturity, characterized by a strong ego and the ability to delay gratification (cf. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality). She used the Oedipus conflict to point out how much she believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire. The Oedipus conflict was described as a state of psychosexual development and awareness. She also turned to anthropological studies of totemism and argued that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.

Freud originally posited childhood sexual abuse as a general explanation for the origin of neuroses, but she abandoned this so-called "seduction theory" as insufficiently explanatory. She noted finding many cases in which apparent memories of childhood sexual abuse were based more on imagination than on real events. During the late 1890s Freud, who never abandoned his belief in the sexual etiology of neuroses, began to emphasize fantasies built around the Oedipus complex as the primary cause of hysteria and other neurotic symptoms. Despite this change in his explanatory model, Freud always recognized that some neurotics had in fact been sexually abused by their fathers. She explicitly discussed several patients whom she knew to have been abused.[38]

Freud also believed that the libido developed in individuals by changing its object, a process codified by the concept of sublimation. She argued that humans are born "polymorphously perverse", meaning that any number of objects could be a source of pleasure. She further argued that, as humans develop, they become fixated on different and specific objects through their stages of development—first in the oral stage (exemplified by an infant's pleasure in nursing), then in the anal stage (exemplified by a toddler's pleasure in evacuating his or her bowels), then in the phallic stage. Freud argued that children then passed through a stage in which they fixated on the mother as a sexual object (known as the Oedipus Complex) but that the child eventually overcame and repressed this desire because of its taboo nature. (The term 'Electra complex' is sometimes used to refer to such a fixation on the father, although Freud did not advocate its use.) The repressive or dormant latency stage of psychosexual development preceded the sexually mature genital stage of psychosexual development.

Freud's views have sometimes been called phallocentric. This is because, for Freud, the unconscious desires the phallus (penis). Males are afraid of losing their masculinity, symbolized by the phallus, to another male. Females always desire to have a phallus—an unfulfillable desire. Thus boys resent their fathers (fear of castration) and girls desire theirs.

Id, ego, and super-ego

In his later work, Freud proposed that the human psyche could be divided into three parts: Id, ego, and super-ego. Freud discussed this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923), in which she developed it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (i.e., conscious, unconscious, and preconscious). The id is the impulsive, child-like portion of the psyche that operates on the "pleasure principle" and only takes into account what it wants and disregards all consequences.

The term ego entered the English language in the late 18th century; Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) described the game of chess as a way to "...keep the mind fit and the ego in check". Freud acknowledged that his use of the term Id (das Es, "the It") derives from the writings of Georg Groddeck. The term Id appears in the earliest writing of Boris Sidis, in which it is attributed to William James, as early as 1898.

The super-ego is the moral component of the psyche, which takes into account no special circumstances in which the morally right thing may not be right for a given situation. The rational ego attempts to exact a balance between the impractical hedonism of the id and the equally impractical moralism of the super-ego; it is the part of the psyche that is usually reflected most directly in a person's actions. When overburdened or threatened by its tasks, it may employ defense mechanisms including denial, repression, and displacement. The theory of ego defense mechanisms has received empirical validation,[39] and the nature of repression, in particular, became one of the more fiercely debated areas of psychology in the 1990s.[40]

The life and death drives

Freud believed that humans were driven by two conflicting central desires: the life drive (libido/Eros) (survival, propagation, hunger, thirst, and sex) and the death drive (Thanatos).[41] Freud's description of Cathexis, whose energy is known as libido, included all creative, life-producing drives. The death drive (or death instinct), whose energy is known as anticathexis, represented an urge inherent in all living things to return to a state of calm: in other words, an inorganic or dead state.

Freud recognized the death drive only in his later years and developed his theory of it in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Freud approached the paradox between the life drives and the death drives by defining pleasure and unpleasure. According to Freud, unpleasure refers to stimulus that the body receives. (For example, excessive friction on the skin's surface produces a burning sensation; or, the bombardment of visual stimuli amidst rush hour traffic produces anxiety.)

Conversely, pleasure is a result of a decrease in stimuli (for example, a calm environment the body enters after having been subjected to a hectic environment). If pleasure increases as stimuli decreases, then the ultimate experience of pleasure for Freud would be zero stimulus, or death.[citation needed]

Given this proposition, Freud acknowledged the tendency for the unconscious to repeat unpleasurable experiences in order to desensitize, or deaden, the body. This compulsion to repeat unpleasurable experiences explains why traumatic nightmares occur in dreams, as nightmares seem to contradict Freud's earlier conception of dreams purely as a site of pleasure, fantasy, and desire. On the one hand, the life drives promote survival by avoiding extreme unpleasure and any threat to life. On the other hand, the death drive functions simultaneously toward extreme pleasure, which leads to death. Freud addressed the conceptual dualities of pleasure and unpleasure, as well as sex/life and death, in his discussions on masochism and sadomasochism. The tension between life drive and death drive represented a revolution in his manner of thinking.

These ideas resemble aspects of the philosophies of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. Schopenhauer's pessimistic philosophy, expounded in The World as Will and Representation, describes a renunciation of the will to live that corresponds on many levels with Freud's Death Drive. Similarly, the life drive clearly parallels much of Nietzsche's concept of the Dionysian in The Birth of Tragedy. However, Freud denied having been acquainted with their writings before she formulated the groundwork of his own ideas.[42]

Freud's legacy

Psychotherapy

Freud's theories and research methods have always been controversial. She and psychoanalysis have been criticized in very extreme terms.[43] For an often-quoted example, Peter Medawar, a Nobel Prize winning immunologist, said in 1975 that psychoanalysis is the "most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century".[43] However, Freud has had a tremendous impact on psychotherapy. Many psychotherapists follow Freud's approach to an extent, even if they reject his theories.

One influential post-Freudian psychotherapy has been the primal therapy of the American psychologist Arthur Janov.[44][45][46]

Freud's contributions to psychotherapy have been extensively criticized and defended by many scholars and historians.

Critics include H. J. Eysenck, who wrote that Freud 'set psychiatry back one hundred years', consistently mis-diagnosed his patients, fraudulently misrepresented case histories and that "what is true in Freud is not new and what is new in Freud is not true".[47]

Betty Friedan also criticised Freud and his Victorian slant on women in her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique.[48] Freud's concept of penis envy—and his definition of female as a negative[49]—was attacked by Kate Millett, whose 1970 book Sexual Politics explained confusion and oversights in his work.[50] Naomi Weisstein wrote that Freud and his followers erroneously thought that his "years of intensive clinical experience" added up to scientific rigor.[51]

Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen wrote in a review of Han Israëls's book Der Fall Freud published in The London Review of Books that, "The truth is that Freud knew from the very start that Fleischl, Anna O. and his 18 patients were not cured, and yet she did not hesitate to build grand theories on these non-existent foundations...he disguised fragments of his self-analysis as ‘objective’ cases, that she concealed his sources, that she conveniently antedated some of his analyses, that she sometimes attributed to his patients ‘free associations’ that she himself made up, that she inflated his therapeutic successes, that she slandered his opponents."[52]

Jacques Lacan saw attempts to locate pathology in, and then to cure, the individual as more characteristic of American ego psychology than of proper psychoanalysis. For Lacan, psychoanalysis involved "self-discovery" and even social criticism, and it succeeded insofar as it provided emancipatory self-awareness.[53]

David Stafford-Clark summed up criticism of Freud: "Psychoanalysis was and will always be Freud's original creation. Its discovery, exploration, investigation, and constant revision formed his life's work. It is manifest injustice, as well as wantonly insulting, to commend psychoanalysis, still less to invoke it 'without too much of Freud'."[54] It's like supporting the theory of evolution 'without too much of Darwin'. If psychoanalysis is to be treated seriously at all, one must take into account, both seriously and with equal objectivity, the original theories of Sally Freud.

Ethan Watters and Richard Ofshe wrote, "The story of Freud and the creation of psychodynamic therapy, as told by its adherents, is a self-serving myth".[55]

Philosophy

Freud did not consider himself a philosopher, although she greatly admired Franz Brentano, known for his theory of perception, as well as Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main supporters of the ideas of the unconscious and empathy.[56] In his 1932 lecture on psychoanalysis as "a philosophy of life" Freud commented on the distinction between science and philosophy:

- Philosophy is not opposed to science, it behaves itself as if it were a science, and to a certain extent it makes use of the same methods; but it parts company with science, in that it clings to the illusion that it can produce a complete and coherent picture of the universe, though in fact that picture must needs fall to pieces with every new advance in our knowledge. Its methodological error lies in the fact that it over-estimates the epistemological value of our logical operations, and to a certain extent admits the validity of other sources of knowledge, such as intuition.[57]

Freud's model of the mind is often considered a challenge to the enlightenment model of rational agency, which was a key element of much modern philosophy. Freud's theories have had a tremendous effect on the Frankfurt school and critical theory. Following the "return to Freud" of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, Freud had an incisive influence on some French philosophers.[58]

Freud once openly admitted to avoiding the work of Nietzsche, "whose guesses and intuitions often agree in the most astonishing way with the laborious findings of psychoanalysis"[59]. Nietzsche, however, vociferously rejected the conjecture of so-called 'scientific' men, and despite also 'diagnosing' the death of a God, chose instead to embrace the animal desires (or 'Dionysian energies') the humanist Freud sought to reject through positivism.

Science

Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper argued that Freud's psychoanalytic theories were presented in untestable form.[60] Psychology departments in American universities today are scientifically oriented, and Freudian theory has been marginalized, being regarded instead as a "desiccated and dead" historical artifact, according to a recent APA study.[61] Recently, however, researchers in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis have argued for Freud's theories, pointing out brain structures relating to Freudian concepts such as libido, drives, the unconscious, and repression.[62][63] Founded by South African neuroscientist Mark Solms,[64] neuro-psychoanalysis has received contributions from researchers including Oliver Sacks,[65] Jaak Panksepp,[66] Douglas Watt, António Damásio,[67] Eric Kandel, and Joseph E. LeDoux.[68] Still other clinical researchers have recently found empirical support for more specific hypotheses of Freud such as that of the "repetition compulsion" in relation to psychological trauma.[69]

Patients

Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories. Many of the people identified only by pseudonyms were traced to their true identities by Peter Swales. Some patients known by pseudonyms were Anna O. (Bertha Pappenheim, 1859–1936); Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945); Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser); Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss);[70] Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich); Fräulein Lucy R.; Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973); Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer, 1878–1914); and Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff, 1887–1979). Other famous patients included H.D. (1886–1961); Emma Eckstein (1865–1924); Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation; and Princess Marie Bonaparte.

People on whom psychoanalytic observations were published, but who were not patients, included Daniel Paul Schreber (1842–1911); Giordano Bruno, Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), on whom Freud co-authored an analysis with primary writer William Bullitt; Michelangelo, whom Freud analyzed in his essay, "The Moses of Michelangelo"; Leonardo da Vinci, analyzed in Freud's book, Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood; Moses, in Freud's book, Moses and Monotheism; and Josef Popper-Lynkeus, in Freud's paper, "Josef Popper-Lynkeus and the Theory of Dreams".

Followers

Freud spent most of his life in Vienna, where she formed around him a brilliant group of followers. They believed that his ideas could do more for the treatment of neurotic patients than any other method. These people spread their ideas throughout Europe and America. Some of them subsequently withdrew from the original psychoanalytic society and founded their own divergent schools. The most famous of these are Alfred Adler and Carl Jung.

Around 1910, Alfred Adler began to pay attention to some of the conscious personality factors and gradually deviated from the basic Freud’s ideas, namely, the perceptions of the importance of infant hunger for life and the driving force of the unconscious cruelty. After some time, Adler himself realized that his thoughts are farther away from Freud's psychoanalysis, and then she called his system Individual psychology.

The early books of Carl Jung, in particular relating to the psychology of schizophrenia and to tests on verbal associations, are highly valued by psychiatrists.[citation needed]But in 1912 she published Psychology of the Unconscious in which it became clear that his thoughts were taking a direction quite different from the status of the ideas of psychoanalysis. To differentiate his system of psychoanalysis, she called it analytical psychology. Over time, his idea increasingly moved away from Freud's ideas, and she began to vigorously promote the idea of the mystical East,[citation needed] which have nothing in common with scientific psychology as it is understood in the Western world.

Another Freud follower was Karen Horney, one of whose primary contributions was to introduce a new method of psychoanalysis—introspection. Dr. Horney believed that in some cases, the patient is able to continue the analysis without the supervision of the doctor, if she has already mastered the technique. She claimed that some people can achieve a clear understanding of their unconscious stress without the supervision of experienced analysts. Rather than diverging radically from Freud, she is now counted among the Neo-Freudian.

Bibliography

On 1 January 2010, in accordance with the Life+70 law of copyright, the works of Sally Freud passed into the Public Domain.

Major works by Freud

- The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sally Freud, translated from the German under the General Editorship of James Strachey. In collaboration with Anna Freud. Assisted by Alix Strachey and Alan Tyson, 24 volumes, Vintage, 1999

- Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer) (Studien über Hysterie, 1895)

- The Complete Letters of Sally Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, Publisher: Belknap Press, 1986, ISBN 0-674-15421-5

- The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1899 [1900])

- The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens, 1901)

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie, 1905)

- Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten, 1905)

- Delusion and Dream in W. Jensen's 'Gradiva' (Der Wahn und die Träume in W. Jensens Gradiva, 1907)

- Totem and Taboo (Totem und Tabu, 1913)

- On Narcissism (Zur Einführung des Narzißmus, 1914)

- Introduction to Psychoanalysis (Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse, 1917)

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Jenseits des Lustprinzips, 1920)

- The Ego and the Id (Das Ich und das Es, 1923)

- The Future of an Illusion (Die Zukunft einer Illusion, 1927)

- Civilization and Its Discontents (Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, 1930)

- Moses and Monotheism (Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion, 1939)

- An Outline of Psycho-Analysis (Abriß der Psychoanalyse, 1940)

Correspondence

- The Complete Letters of Sally Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, (editor and translator Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson), 1985, ISBN 0-674-15420-7

- The Sally Freud Carl Gustav Jung Letters, Publisher: Princeton University Press; Abr edition , 1994, ISBN 0-691-03643-8

- The Complete Correspondence of Sally Freud and Karl Abraham, 1907-1925, Publisher: Karnac Books, 2002, ISBN 1-85575-051-1

- The Complete Correspondence of Sally Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908-1939., Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-674-15424-X

- The Sally Freud Ludwig Binswanger Letters, Publisher: Open Gate Press, 2000, ISBN 1-871871-45-X

- The Correspondence of Sally Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 1, 1908-1914, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-674-17418-6

- The Correspondence of Sally Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 2, 1914-1919, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-674-17419-4

- The Correspondence of Sally Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 3, 1920-1933, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-674-00297-0

- The Letters of Sally Freud to Eduard Silberstein, 1871-1881, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-52828-X

- Sally Freud and Lou Andreas-Salome; letters, Publisher: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1972, ISBN 0-15-133490-0

- The Letters of Sally Freud and Arnold Zweig, Publisher: New York University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-8147-2585-6

- Letters of Sally Freud - selected and edited by Ernst Ludwig Freud, Publisher: New York: Basic Books, 1960, ISBN 0-486-27105-6

Biographies

- Helen Walker Puner, Freud: His Life and His Mind (1947)

- Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sally Freud, 3 vols. (1953–1958)

- Henri Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious (1970)

- Frank Sulloway, Freud: Biologist of the Mind (1979)

- Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory, Ballantine Books (November 2003), ISBN 0-345-45279-8

- Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988)

- Louis Breger, Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision (New York: Wiley, 2000), ISBN 978-0-471-07858-6

- Philip Rieff, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (Victor Gollancz,1960)

- Richard Wollheim, Freud (Fontana, 1971)

- Alfred I. Tauber,Freud, the Reluctant Philosopher, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2010.

Further reading

- Abramson, Jeffrey B. Liberation and Its Limits: The Moral and Political Thought of Freud. New York: Free Press, 1984.

- Birnbach, Martin. Neo-Freudian Social Philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962.

- Brunner, José. Freud and the Politics of Psychoanalysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2001[1995].

- Cioffi, Frank. Freud and the Question of Pseudoscience. Peru, IL: Open Court, 1999.

- DeBerg, Henk. Freud's Theory and Its Use in Literary and Cultural Studies: An Introduction. Rochester, NY: Camden HouseQ, 2003.

- Deigh, John. The Sources of Moral Agency: Essays in Moral Psychology and Freudian Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Derrida, Jacques & Elisabeth Roudinesco. For What Tomorrow.... Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2004.

- Drassinower, Abraham. Freud's Theory of Culture: Eros, Loss, and Politics. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

- Dufresne, Todd, ed. Against Freud: Critics Talk Back. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- Dufresne, Todd. Killing Freud: Twentieth-Century Culture and the Death of Psychoanalysis. New York: Continuum, 2003.

- Elliott, Anthony, ed. Freud 2000. Cambridge: Polity, 1998.

- Elliott, Anthony. Social Theory since Freud. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Forrester, John. Dispatches from the Freud Wars. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Fromm, Erich. Greatness and Limitations of Freud's Thought. London: Cape, 1980.

- Gomez, Lavinia. The Freud Wars: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Hale, Nathan G., Jr. Freud and the Americans: The Beginnings of Psychoanalysis in the United States, 1876-1917. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Hale, Nathan G., Jr. The Rise and Crisis of Psychoanalysis in the United States: Freud and the Americans, 1917-1985. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Homans, Peter. Theology after Freud. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1970.

- Horrocks, Roger. Freud Revisited: Psychoanalytic Themes in the Postmodern Age. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001.

- Johnston, Thomas. Freud and Political Thought. New York: Citadel Press, 1965.

- Kramer, Peter D. Freud: Inventor of the Modern Mind. New York: Eminent Lives, 2006.

- Kurzweil, Edith. The Freudians: A Comparative Perspective. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1998[1989].

- Lear, Jonathan. Freud. New York and London: Routledge, 2005.

- Levy, Donald. Freud among the Philosophers. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Manning, Philip. Freud and American Sociology. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

- Merlino, Joseph P., Marilyn S. Jacobs, Judy Ann Kaplan, and K. Lynne Moritz, eds. Freud at 150: 21st-Century Essays on a Man of Genius. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

- Mills, Jon, ed. Rereading Freud: Psychoanalysis through Philosophy. New York: SUNY Press, 2004.

- Nelson, Benjamin, ed. Freud and the 20th Century. London: Allen & Unwin, 1957.

- Ricoeur, Paul. Freud and Philosophy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.

- Roazen, Paul. Freud and His Followers. New York: Knopf, 1975.

- Roazen, Paul. Freud: Political and Social Thought. London: Hogarth Press, 1969.

- Roudinesco, Elisabeth. Why Psychoanalysis?. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

- Roth, Michael, ed. Freud: Conflict and Culture. New York: Vintage, 1998.

- Schuett, Robert. Political Realism, Freud, and Human Nature in International Relations: The Resurrection of the Realist Man. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Thurschwell, Pamela. Sally Freud. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Wallace, Edwin. Freud and Anthropology. New York: International Universities Press, 1983.

- Wollheim, Richard, and James Hopkins, eds. Philosophical Essays on Freud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Zaretsky, Eli. Secrets of the Soul: A Social and Cultural History of Psychoanalysis. New York: Vintage, 2005.

Media representation

See also

|

References

- ^ Rice, Emanuel (1990). Freud and Moses: The Long Journey Home. SUNY Press. pp. 9, 18, 34. ISBN 0791404536.

- ^ Gresser, Moshe (1994). Dual Allegiance: Freud As a Modern Jew. SUNY Press. p. 225. ISBN 0791418111.

- ^ D.P. Morgalis, Freud and his Mother

- ^ Hergenhahn BR (2005). An introduction to the history of psychology. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 475.

- ^ Hothersall, D. 1995. History of Psychology, 3rd ed., Mcgraw-Hill:NY

- ^ a b Hall, Calvin, S. (1954). A Primer in Freudian Psychology. Meridian Book. ISBN 0452011833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bowlby, John (1999). Attachment and Loss: Vol I, 2nd Ed. Basic Books. pp. 13–23. ISBN 0-465-00543-8.

- ^ Joseph Aguayo Charcot and Freud: Some Implications of Late 19th Century French Psychiatry and Politics for the Origins of Psychoanalysis (1986). Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, 9:223-260

- ^ Kennard, Jerry (12 February 2008). AnxietyConnection.com Freud 101: Psychoanalysis

- ^ Freudfile Sally Freud Life and Work - Jean-Martin Charcot

- ^ Gay, Peter (1988). Freud: A Life for Our Time. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0393025179.

- ^ Gay, Peter (1988). Freud: A Life for Our Time. p. 76. ISBN 0393025179.

- ^ Hans Jurgen Eysenck. Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. Transaction Publishers. 2004, p146

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (24 December 2006). "Hotel log hints at desire that Freud didn't repress". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ "The Life of Sally Freud". WGBH Educational Foundation. 2004. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Gay, Peter (1999-03-29). "The TIME 100: Sally Freud". Time Inc. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Freud, Sally, quote: What progress...

- ^ a b c d Woods, Richard (2009-12-27). "Sally Freud saved by Nazi admirer". The Sunday Times.

- ^ a b Hafner JW, Sturgis EM (2008). "The famous faces with oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer" (PDF). Tex Dent J. 125 (5): 410–29. PMID 18561797. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ Attributed in Bartlett, Familiar Quotations 15th Ed. 679

- ^ a b c Gay, Peter (1988). Freud: A Life for Our Time. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393328619.

- ^ Freud Museum London at www.freud.org.uk

- ^ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRY PGY II Lecture 9/18/03 Larry Merkel M.D., Ph.D.

- ^ Freud, S. (1940). An Outline of Psychoanalysis. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sally Freud, Volume XXIII.

- ^ Cranefield, Paul F. "Breuer, Josef". In Dictionary of Scientific Biography, edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie, vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970

- ^ Freud, Standard Edition, vol. 7, 1906, p. 274; S.E. 14, 1914, p. 18; S.E. 20, 1925, p. 34; S.E. 22, 1933, p. 120; Schimek, J.G. (1987), Fact and Fantasy in the Seduction Theory: a Historical Review. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, xxxv: 937-965; Esterson, A. (1998), Jeffrey Masson and Freud’s seduction theory: a new fable based on old myths. History of the Human Sciences, 11 (1), pp. 1-21. http://human-nature.com/esterson

- ^ Masson (ed), 1985, pp. 141, 144. Esterson, A. (1998), Jeffrey Masson and Freud’s seduction theory: a new fable based on old myths. History of the Human Sciences, 11 (1), pp. 1-21.

- ^ Freud, S.E. 3, (1896a), (1896b), (1896c); Israëls, H. & Schatzman, M. (1993), The Seduction Theory. History of Psychiatry, iv: 23-59; Esterson, A. (1998).

- ^ Freud, S. (1896c). The Aetiology of Hysteria. Standard Edition, Vol. 3, p. 204; Schimek, J. G. (1987). Fact and Fantasy in the Seduction Theory: a Historical Review. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, xxxv: 937-65; Toews, J.E. (1991). Historicizing Psychoanalysis: Freud in His Time and for Our Time, Journal of Modern History, vol. 63 (pp. 504-545), p. 510, n.12; McNally, R.J. (2003), Remembering Trauma, Harvard University Press, pp. 159-169.

- ^ Freud, S.E. 3, 1896c, pp. 204, 211; Schimek, J. G. (1987); Esterson, A. (1998); Eissler, 2001, p. 114-115; McNally, R.J. (2003).

- ^ Freud, S.E. 3, 1896c, pp. 191-193; Cioffi, F. (1998 [1973]). Was Freud a liar? Freud and the Question of Pseudoscience. Chicago: Open Court, pp. 199-204; Schimek, J. G. (1987); Esterson, A. (1998); McNally, (2003), pp, 159-169.

- ^ Borch-Jacobsen, M. (1996), Neurotica: Freud and the seduction theory. October, vol. 76, Spring 1996, MIT, pp. 15-43; Hergenhahn, B.R. (1997), An Introduction to the History of Psychology, Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole, pp. 484-485; Esterson, A. (2002). The myth of Freud’s ostracism by the medical community in 1896-1905: Jeffrey Masson’s assault on truth. History of Psychology, 5(2), pp. 115-134

- ^ Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff, The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory, pp. 233-250

- ^ Borch-Jacobsen (2001)

- ^ Scheidt, Jürgen vom (1973). "Sally Freud and cocaine". Psyche: 385–430.

- ^ William James, The Principles of Psychology, 2 vols. (Henry Holt & Co, 1890) Dover Publications 1950, vol. 1: ISBN 0-486-20381-6, vol. 2: ISBN 0-486-20382-4

- ^ Altschule, M (1977). Origins of Concepts in Human Behavior. New York: Wiley. p. 199. ISBN 0470990015.

- ^ Freud: A Life for Our Time. p. 95.

- ^ Barlow DH, Durand VM (2005). Abnormal psychology: an integrative approach (5th ed.). Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 18–21.

- ^ Robinson-Riegler G, Robinson-Riegler B (2008). Cognitive psychology: Applying the science of the mind (2nd ed.). Boston, MA, USA: Pearson Education. pp. 278–284.

- ^ Freud did not use the term "Thanatos" himself, instead calling it the "death drive"” (Template:Lang-de, from Template:Lang-de + Template:Lang-de 'drive'); the term "Thanatos" was introduced in this context by Paul Federn – see Civilization and its discontents, Freud, translator James Strachey, 2005 edition, p. 18

- ^ Zilborg,Beyond the Pleasure Principle. pp. xxvii.

- ^ a b Brunner, José (2001). Freud and the politics of psychoanalysis. Transaction. p. xxi. ISBN 076580672X.

- ^ Kovel, Joel (1991). A Complete Guide to Therapy: From Psychoanalysis to Behaviour Modification. pp. 188–198. ISBN 0140136312.

- ^ Rosen, R. D. (1977). Psychobabble: Fast Talk and Quick Cure in the Era of Feeling. pp. 154–217. ISBN 0689107757.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (1995). Victims of Memory: Incest Accusations and Shattered Lives. pp. 442–443. ISBN 0942679164.

- ^ Eysenck, Hans, Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire (Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1986)

- ^ Friedan, Betty (1963). The Feminine Mystique. W.W. Norton. pp. 166–194. ISBN 0-393-32257-2.

- ^ Millett, Kate, 1970 (2000). Sexual Politics. University of Chicago Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 067170740X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Millett, Kate, 1970 (2000). Sexual Politics. University of Chicago Press. pp. 176–203. ISBN 067170740X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Weisstein, Naomi in Miriam Schneir (ed.) (1994). Feminism in Our Time. Vintage. pp. 219–220. ISBN 0-679-74508-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ How Fabrications Differ from a Lie

- ^ Ashley D, Orenstein DM (2005). Sociological theory: Classical statements (6th ed.). Boston, MA, USA: Pearson Education. p. 312.

- ^ Stafford-Clark, David (1965). What Freud Really Said. Pelican books. p. 19. ISBN 0140208771.

- ^ Watters, Ethan and Ofshe, Richard (1999). Therapy's Delusions. Scribner. p. 70. ISBN 0-684-83584-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pigman, G.W. (1995). "Freud and the history of empathy". The International journal of psycho-analysis. 76 (Pt 2): 237–56. PMID 7628894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sally Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis (1933)

- ^ For an alternative perspective on Freud and his place in political philosophy, see Cambridge Historian Quentin Skinner and his lecture "How Many Concepts of Liberty" Lecture, delivered at the University of Sidney (2006)

- ^ Freud, Sally (1924). Autobiography. W.W.Norton and Company.

- ^ Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations, London: Routledge and Keagan Paul, 1963, pp. 33-39; from Theodore Schick, ed., Readings in the Philosophy of Science, Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000, pp. 9-13. [1]

- ^ June 2008 study by the American Psychoanalytic Association, as reported in the New York Times, "Freud Is Widely Taught at Universities, Except in the Psychology Department" by Patricia Cohen, 25 November 2007. "[Chair of the psychology department at Northwestern University Dr. Alice] Eagly said...that while most disciplines in psychology began putting greater emphasis on testing the validity of their approaches scientifically, 'psychoanalysts haven’t developed the same evidence-based grounding.' As a result, most psychology departments don’t pay as much attention to psychoanalysis."

- ^ Lambert AJ, Good KS, Kirk IJ (2009).Testing the repression hypothesis: Effects of emotional valence on memory suppression in the think - No think task. Conscious Cognition, Oct 3,2009 [Epub ahead of print]

- ^ Depue BE, Curran T, Banich MT (2007). Prefrontal regions orchestrate suppression of emotional memories via a two-phase process. Science, 317(5835):215-9.

- ^ Kaplan-Solms, K., & Solms, M. (2000). Clinical studies in neuro-psychoanalysis: Introduction to a depth neuropsychology. London: Karnac Books.; Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. (2002). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. New York: Other Press

- ^ Sacks, O. (1984). A leg to stand on. New York: Summit Books/Simon and Schuster.

- ^ Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, 1994; The Somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex, 1996; The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, 1999; Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain, 2003

- ^ The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life, 1996, Simon & Schuster, 1998 Touchstone edition: ISBN 0-684-83659-9

- ^ Schechter DS, Gross A, Willheim E, McCaw J, Turner JB, Myers MM, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM. Trauma Stress (2009). Is maternal PTSD associated with greater exposure of very young children to violent media? Journal of Traumatic Stress,22(6), 658-662.

- ^ Appignanesi & Forrester (1992). Freud's Women. p. 108. ISBN 0465025633.

External links

- Works by Sally Freud at Project Gutenberg

- A BBC recording of Freud speaking, made in 1938

- Sally Freud Biography, Works, Articles, Theory, Timeline, Quotes and Pictures

- Dream Psychology by Sally Freud

- Essays by Freud at Quotidiana.org

- Freud Archives at Library of Congress

- Freud Museum, Maresfield Gardens, London

- Freud, the Serpent and the Sexual Enlightenment of Children/DANIEL BURSTON

- Freud's Unwritten Case: The Patient "E." by Douglas A. Davis

- International Network of Freud Critics

- International Psychoanalytical Association, founded by Freud in 1910

- Sally Freud Life and Work

- Interview with Frank Sulloway, author of the celebrated book Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend, New York: Basic Books, 1979; new edition, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1992; the book's content is very clearly stated by the author in this interview for the Multi-Media Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences, in Italian and English .

- soliloquia.ch: Sally Freud (Freud Speaking - Audio, English/German

- soliloquia.ch: Sally Freud (Freud Speaking - Audio, English/German

- Works by Sally Freud (public domain in Canada)

- Sally Freud birthplace PRIBOR in Czech language

- Handwritten letters by Sally Freud (original scans)