Snake worship

The worship of serpent deities is present in several old cultures, particularly in religion and mythology, where snakes were seen as entities of strength and renewal.

African mythology

In Africa the chief centre of serpent worship was Dahomey, but the cult of the python seems to have been of exotic origin, dating back to the first quarter of the 17th century. By the conquest of Whydah the Dahomeyans were brought in contact with a people of serpent worshippers, and ended by adopting from them the beliefs which they at first despised. At Whydah, the chief centre, there is a serpent temple, tenanted by some fifty snakes. Every python of the danh-gbi kind must be treated with respect, and death is the penalty for killing one, even by accident. Danh-gbi has numerous wives, who until 1857 took part in a public procession from which the profane crowd was excluded; a python was carried round the town in a hammock, perhaps as a ceremony for the expulsion of evils. The rainbow-god of the Ashanti was also conceived to have the form of a snake. His messenger was said to be a small variety of boa, but only certain individuals, not the whole species, were sacred. In many parts of Africa the serpent is looked upon as the incarnation of deceased relatives. Among the Amazulu, as among the Betsileo of Madagascar, certain species are assigned as the abode of certain classes. The Maasai, on the other hand, regard each species as the habitat of a particular family of the tribe.[citation needed]

Eva Meyerowitz wrote of an earthenware pot that was stored at the Museum of Achimota College in Gold Coast. The base of the neck of this pot is surrounded by the rainbow snake (Meyerowitz 1940, p. 48). The legend of this creature explains that the rainbow snake only emerged from its home when it was thirsty. Keeping its tail on the ground the snake would raise its head to the sky looking for the rain god. As it drank great quantities of water, the snake would spill some which would fall to the earth as rain (Meyerowitz 1940, p. 48).

There are four other snakes on the sides of this pot: Danh – gbi, the life giving snake, Li, for protection, Liwui, which was associated with Wu, god of the sea, and Fa, the messenger of the gods (Meyerowitz 1940, p. 48). The first three snakes Danh – gbi, Li, Liwui were all worshipped at Whydah, Dahomey where the serpent cult originated (Meyerowitz 1940, p. 48). For the Dahomeans, the spirit of the serpent was one to be feared as he was unforgiving (Nida & Smalley 1959, p. 17). They believed that the serpent spirit could manifest itself in any long, winding objects such as plant roots and animal nerves. They also believed it could manifest itself as the umbilical cord, making it a symbol of fertility and life (Nida & Smalley 1959, p. 17).

Mami Wata is a water spirit or class of spirits associated with fertility and healing, usually depicted as a woman holding a large snake or with the lower body of a serpent or fish. She is worshipped in West, Central, and Southern Africa and the African diaspora.[citation needed]

African diasporic religion

In Haitian Vodou, the creator loa Damballa is represented as a serpent, and his wife Ayida-Weddo is called the "rainbow serpent."[3] In West African mythology, Ayida-Weddo is believed to hold up the sky.[4][5] Simbi are a type of serpentine loa in Haitian Vodou. They are associated with water and sometimes are believed to act as psychopomps serving Papa Legba.[citation needed]

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians worshiped snakes, especially the cobra. The cobra was not only associated with Ra, but also many other deities such as Wadjet, Renenutet, Nehebkau, and Meretseger. Serpents could also be evil and harmful such as the case of Apep and Set. They were also referenced in the Book of the Dead, in which Spell 39 was made to help repel an evil snake in the underworld. "Get back! Crawl away! Get away from me, you snake! Go, be drowned in the Lake of the Abyss, at the place where your father commanded that the slaying of you should be carried out."[6]

Wadjet was the patron goddess of Upper Egypt, and was represented as a cobra with spread hood, or a cobra-headed woman. She later became one of the protective emblems on the pharaoh's crown once Upper and Lower Egypt were united. She was said to 'spit fire' at the pharaoh's enemies, and the enemies of Ra. Sometimes referred to as one of the eyes of Ra, she was often associated with the lioness goddess Sekhmet, who also bore that role.

Ancient Near East

Ancient Mesopotamians and Semites believed that snakes were immortal because they could infinitely shed their skin and appear forever youthful, appearing in a fresh guise every time. [1] The Sumerians worshipped a serpent god or goddess named Ningishzida, an ancestor of Gilgamesh. Before the arrival of the Israelites, snake cults were well established in Canaan in the Bronze Age, for archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo,[7] one at Gezer,[8] one in the sanctum sanctorum of the Area H temple at Hazor,[9] and two at Shechem.[10]

In the surrounding region, serpent cult objects figured in other cultures. A late Bronze Age Hittite shrine in northern Syria contained a bronze statue of a god holding a serpent in one hand and a staff in the other.[11] In sixth-century Babylon a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila.[12] At the Babylonian New Year's festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker, and a goldsmith two images, one of which "shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu".[13] At the tell of Tepe Gawra, at least seventeen Early Bronze Age Assyrian bronze serpents were recovered.[14]

Ancient Europe

Serpent worship was well known in ancient Europe. The Roman genius loci took the form of a serpent.[citation needed]

In Italy, the Marsian goddess Angitia, whose name derives from the word for "serpent," was associated with witches, snakes, and snake-charmers. Angitia is believed to have also been a goddess of healing. Her worship was centered in the Central Apennine region.[15]

A snake was kept and fed with milk during rites dedicated to Potrimpus, a Prussian god. On the Iberian Peninsula there is evidence that before the introduction of Christianity, and perhaps more strongly before Roman invasions, serpent worship was a standout feature of local religions (see Sugaar). To this day there are numerous traces in European popular belief, especially in Germany, of respect for the snake, possibly a survival of ancestor worship: The "house snake" cares for the cows and the children, and its appearance is an omen of death; and the lives of a pair of house snakes are often held to be bound with that of the master and the mistress.[citation needed] Tradition states that one of the Gnostic sects known as the Ophites caused a tame serpent to coil around the sacramental bread, and worshipped it as the representative of the Savior.[citation needed]

Greek mythology

Serpents figured prominently in archaic Greek myths. According to some sources, Ophion ("serpent", a.k.a. Ophioneus), ruled the world with Eurynome before the two of them were cast down by Kronos and Rhea. The oracles of the Ancient Greeks were said to have been the continuation of the tradition begun with the worship of the Egyptian cobra goddess, Wadjet. We learn from Herodotus of a great serpent which defended the citadel of Athens.[citation needed]

The Minoan Snake Goddess brandished a serpent in either hand, perhaps evoking her role as source of wisdom, rather than her role as Mistress of the Animals (Potnia Theron), with a leopard under each arm.[citation needed] It is not by accident that later the infant Herakles, a liminal hero on the threshold between the old ways and the new Olympian world,[citation needed] also brandished the two serpents that "threatened" him in his cradle. Although the Classical Greeks were clear that these snakes represented a threat, the snake-brandishing gesture of Herakles is the same as that of the Cretan goddess.[citation needed]

Typhon, the enemy of the Olympian gods, is described as a vast grisly monster with a hundred heads and a hundred serpents issuing from his thighs, who was conquered and cast into Tartarus by Zeus, or confined beneath volcanic regions, where he is the cause of eruptions. Typhon is thus the chthonic figuration of volcanic forces. Amongst his children by Echidna are Cerberus (a monstrous three-headed dog with a snake for a tail and a serpentine mane), the serpent-tailed Chimaera, the serpent-like water beast Hydra, and the hundred-headed serpentine dragon Ladon. Both the Lernaean Hydra and Ladon were slain by Herakles.

Python, an enemy of Apollo, was always represented in vase-paintings and by sculptors as a serpent. Apollo slew Python and made her former home, Delphi, his own oracle. The Pythia took her title from the name Python.[16]

Amphisbaena, a Greek word, from amphis, meaning "both ways", and bainein, meaning "to go", also called the "Mother of Ants", is a mythological, ant-eating serpent with a head at each end. According to Greek mythology, the mythological amphisbaena was spawned from the blood that dripped from Medusa the Gorgon's head as Perseus flew over the Libyan Desert with her head in his hand.[citation needed]

Medusa and the other Gorgons were vicious female monsters with sharp fangs and hair of living, venomous snakes whose origins predate the written myths of Greece and who were the protectors of the most ancient ritual secrets. The Gorgons wore a belt of two intertwined serpents in the same configuration of the caduceus. The Gorgon was placed at the highest point and central of the relief on the Parthenon.[citation needed]

Asclepius, the son of Apollo and Koronis, learned the secrets of keeping death at bay after observing one serpent bringing another (which Asclepius himself had fatally wounded) healing herbs. To prevent the entire human race from becoming immortal under Asclepius's care, Zeus killed him with a bolt of lightning. Asclepius' death at the hands of Zeus illustrates man's inability to challenge the natural order that separates mortal men from the gods. In honor of Asclepius, snakes were often used in healing rituals. Non-poisonous Aesculapian snakes were left to crawl on the floor in dormitories where the sick and injured slept. The author of the Bibliotheca claimed that Athena gave Asclepius a vial of blood from the Gorgons. Gorgon blood had magical properties: if taken from the left side of the Gorgon, it was a fatal poison; from the right side, the blood was capable of bringing the dead back to life. However Euripides wrote in his tragedy Ion that the Athenian queen Creusa had inherited this vial from her ancestor Erichthonios, who was a snake himself. In this version the blood of Medusa had the healing power while the lethal poison originated from Medusa's serpents.[citation needed] Zeus placed Asclepius in the sky as the constellation Ophiucus, "the Serpent-Bearer".[citation needed] The modern symbol of medicine is the rod of Asclepius, a snake twining around a staff, while the symbol of pharmacy is the bowl of Hygieia,[17] a snake twining around a cup or bowl. Hygieia was a daughter of Asclepius.

Laocoön was allegedly a priest of Poseidon (or of Apollo, by some accounts) at Troy; he was famous for warning the Trojans in vain against accepting the Trojan Horse from the Greeks, and for his subsequent divine execution. Poseidon (some say Athena), who was supporting the Greeks, subsequently sent sea-serpents to strangle Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. Another tradition states that Apollo sent the serpents for an unrelated offense, and only unlucky timing caused the Trojans to misinterpret them as punishment for striking the Horse.

Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great and a princess of the primitive land of Epirus, had the reputation of a snake-handler, and it was in serpent form that Zeus was said to have fathered Alexander upon her; tame snakes were still to be found at Macedonian Pella in the 2nd century AD (Lucian, Alexander the false prophet) and at Ostia a bas-relief shows paired coiled serpents flanking a dressed altar, symbols or embodiments of the Lares of the household, worthy of veneration (Veyne 1987 illus p 211).

Aeetes, the king of Colchis and father of the sorceress Medea, possessed the Golden Fleece. He guarded it with a massive serpent that never slept. Medea, who had fallen in love with Jason of the Argonauts, enchanted it to sleep so Jason could seize the Fleece.

See Lamia (mythology).

Nordic mythology

Jörmungandr, alternately the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent, of the Norse mythology, is the middle child of Loki and the giantess Angrboða. However, there is nothing to indicate that the Norsemen ever worshipped this or other snake-like beings such as Fafnir.

According to the Prose Edda, Odin took Loki's three children, Fenrisúlfr, Hel and Jörmungandr. He tossed Jörmungandr into the great ocean that encircles Midgard. The serpent grew so big that he was able to surround the Earth and grasp his own tail, and as a result he earned the alternate name of the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent. Jörmungandr's arch enemy is the god Thor.

Australian mythology

In Australia, various Aboriginal mythologies tell of a huge python, known by a variety of names but universally referred to as the Rainbow Serpent, that was said to have created the landscape, embodied the spirit of fresh water, and punished lawbreakers. The Aborigines in southwest Australia called the serpent the Waugyl, while the Warramunga of the east coast worshipped the mythical Wollunqua.[citation needed]

Cambodian mythology

Serpents, or nāgas, play a particularly important role in Cambodian mythology. A well-known story explains the emergence of the Khmer people from the union of Indian and indigenous elements, the latter being represented as nāgas. According to the story, an Indian brahmana named Kaundinya came to Cambodia, which at the time was under the dominion of the naga king. The naga princess Soma sallied forth to fight against the invader but was defeated. Presented with the option of marrying the victorious Kaundinya, Soma readily agreed to do so, and together they ruled the land. The Khmer people are their descendants.[18]

Christian mythology

Contemporary Christian culture identifies the snake as a symbol of evil and of the devil himself. Snake handling is a religious ritual in a small number of Christian churches in the U.S., usually characterized as rural and Pentecostal, particularly the Church of God with Signs Following. Practitioners believe it dates to antiquity and quote the Bible to support the practice, especially:

- "They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." (Mark 16:18)

- "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you." (Luke 10:19)

Hindu mythology

Snake worship refers to the high status of snakes or (nagas) in Hindu mythology. Nāga (Sanskrit:नाग) is the Sanskrit and Pāli word for a deity or class of entity or being, taking the form of a very large snake, found in Hinduism and Buddhism. The use of the term nāga is often ambiguous, as the word may also refer, in similar contexts, to one of several human tribes known as or nicknamed "Nāgas"; to elephants; and to ordinary snakes, particularly the King Cobra and the Indian Cobra, the latter of which is still called nāg in Hindi and other languages of India. A female nāga is a nāgī. The Snake primarily represents rebirth, death and mortality, due to its casting of its skin and being symbolically "reborn". Over a large part of India there are carved representations of cobras or nagas or stones as substitutes. To these human food and flowers are offered and lights are burned before the shrines. Among some South Indians, a cobra which is accidentally killed is burned like a human being; no one would kill one intentionally. The serpent-god's image is carried in an annual procession by a celibate priestess.

The Nairs of Kerala and Tulu Bunts of Karnataka in South India still carry out these ancient customs.

At one time there were many prevalent different renditions of the serpent cult located in India. In Northern India, a masculine version of the serpent named Nagaraja and known as the “king of the serpents” was worshipped. Instead of the “king of the serpents,” actual live snakes were worshipped in South India (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 1). The Manasa-cult in Bengal, India, however, was dedicated to the anthropomorphic serpent goddess, Manasa (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 1).

Nāgas form an important part of Hindu mythology. They play prominent roles in various legends:

- Shesha (Aadi shesha, Ananda) on whom Vishnu does yoga nidra(Ananda shayana).

- Vasuki is the king of Nagas.

- Kaliya poisoned the Yamuna river where he lived. Krishna subdued Kaliya and compelled him to leave the river.

- Manasa is the queen of the snakes.

- Astika is half Brahmin and half naga.

Shiva is depicted wearing a snake around his neck.

Nag panchami is an important Hindu festival associated with snake worship which takes place of the fifth day of Shravana (July-August). Snake idols are offered gifts of milk and incense to help the worshipper to gain knowledge, wealth, and fame.

Different districts of Bengal celebrate the serpent in various ways. In the districts of East Mymensing, West Sylhet, and North Tippera, serpent-worship rituals were very similar, however (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 5). On the very last day of the Bengali month Shravana, all of these districts celebrate serpent-worship each year (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 5). Regardless of their class and station, every family during this time created a clay model of the serpent-deity – usually the serpent-goddess with two snakes spreading their hoods on her shoulders. The people worshipped this model at their homes and sacrificed a goat or a pigeon for the deity’s honor (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 5). Before the clay goddess was submerged in water at the end of the festival, the clay snakes were taken from her shoulders. The people believed that the earth these snakes were made from cured illnesses, especially children’s diseases (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 6).

These districts also worshipped an object known as a Karandi (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 6). Resembling a small house made of cork, the Karandi is decorated with images of snakes, the snake goddess, and snake legends on its walls and roof (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 6). The blood of sacrificed animals was sprinkled on the Karandi and it also was submerged in the river at the end of the festival (Bhattacharyya 1965, p. 6).

Korean mythology

In Korean mythology, Eobshin, the wealth goddess, appears as an eared, black snake. Chilseongshin (the Jeju Island equivalent to Eobshin) and her seven daughters are all snakes. These goddesses are deities of orchards, courts, and protect the home. According to the Jeju Pungtorok, "The people fear snakes. They worship it as a god...When they see a snake, they call it a great god, and do not kill it or chase it away." The reason for snakes symbolizing worth was because they ate rats and other pests.[19]

Native American mythology

North America

Some[which?] of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas give reverence to the rattlesnake as grandfather and king of snakes who is able to give fair winds or cause tempest. Among the Hopi of Arizona snake-handling figures largely in a dance to celebrate the union of Snake Youth (a Sky spirit) and Snake Girl (an Underworld spirit). The rattlesnake was worshipped in the Natchez temple of the sun. The Mound Builders evidently reverenced the serpent, as the Serpent Mound demonstrates, though we are unable to unravel the particular associations.

Mesoamerica

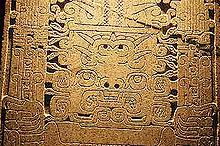

The Maya deity Kukulkan and the Aztec Quetzalcoatl (both meaning "feathered serpent") figured prominently in their respective cultures of origin. Kukulkan (Q'uq'umatz in K'iche' Maya) is associated with Vision Serpent iconography in Maya art.[20] Kukulkan was an official state deity of Itza in the northern Yucatan.[21] In many Mesoamerican cultures, the serpent was regarded as a portal between two worlds.[citation needed]

The worship of Quetzalcoatl dates back to as early as the 1st century BC at Teotihuacan.[22] In the Postclassic period (AD 900-1519), the cult was centered at Cholula. Quetzalcoatl was associated with wind, the dawn, the planet Venus as the morning star, and was a tutelary patron of arts, crafts, merchants, and the priesthood.[23]

South America

Serpents figure prominently in the art of the pre-Incan Chavín culture, as can be seen at the type-site of Chavín de Huántar in Peru.[24] In Chile the Mapuche mythology featured a serpent figure in stories about a deluge.[citation needed] Lake Guatavita in Colombia also maintains a Cacique legend of a "Serpent God" living in the waters, which the tribe worshiped by placing gold and silver jewelry into the lake.[citation needed]

Images related to snake worship

-

The Snake God Naga and his consort.The photo is taken at the cave temples clusters of Ajanta, Maharashtra, India

-

A motif of snake goddess. Carving on volcanic rock at the Kailash Temple, Ellora, India

-

A snake worship altar from south India

Other snake gods

- Aušlavis

- Damballah

- Degei

- Glycon

- Kadru

- Manasa

- Nagaraja

- Nagaradhane

- Nehebkau

- Ningizzida

- Quetzalcoatl

- Rainbow Serpent

- Ratumaibulu

- Set (serpent god)

- Minoan Snake Goddess

- Takshaka

- Ungud

- Vasuki

- Wollunqua

- Zombi (African god)

See also

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

- ^ Jell-Bahlsen 1997, p. 105

- ^ Chesi 1997, p. 255

- ^ Leah Gordon (1985), page 50-1 The Book of Vodou, Barron's Educational Series ISBN 978-0-7641-5249-8.

- ^ Shannon R. Turlington (2002), page 84 The Complete Idiot's Guide to Voodoo, Pearson Education, Inc ISBN 978-0-02-864236-9.

- ^ Neil Philip (1999), page 6, Myths and Legends Explained, Dorling Kindersley ISBN 978-0-7566-2871-0.

- ^ Faulkner, Raymond O. (2010). Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. New York, NY: Fall River Press. pp. 67–68.

- ^ Gordon Loud, Megiddo II: Plates plate 240: 1, 4, from Stratum X (dated by Loud 1650-1550 BC) and Stratum VIIB (dated 1250-1150 BC), noted by Karen Randolph Joines, "The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult" Journal of Biblical Literature 87.3 (September 1968:245-256) p. 245 note 2.

- ^ R.A.S. Macalister, Gezer II, p. 399, fig. 488, noted by Joiner 1968:245 note 3, from the high place area, dated Late Bronze Age.

- ^ Yigael Yadin et al. Hazor III-IV: Plates, pl. 339, 5, 6, dated Late Bronze Age II (Yadiin to Joiner, in Joiner 1968:245 note 4).

- ^ Callaway and Toombs to Joiner (Joiner 1968:246 note 5).

- ^ Maurice Viera, Hittite Art (London, 1955) fig. 114.

- ^ Leonard W. King, A History of Babylon, p. 72.

- ^ Pritchard ANET, 331, noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 8.

- ^ E.A. Speiser, Excavations at Tepe Gawra: I. Levels I-VIII, p. 114ff., noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 9.

- ^ Emma Dench, From Barbarians to New Men: Greek, Roman, and Modern Perceptions of Peoples from the Central Apennines (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), pp. 24, 159.

- ^ Karl Kerenyi The Gods of the Greeks 1951:136.

- ^ "History of the Bowl of Hygeia award | Drug Topics". Drugtopics.modernmedicine.com. 2002-10-07. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.13.

- ^ http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=581047&mobile&categoryId=1627

- ^ Mary Miller, Maya Art and Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

- ^ Sharer, Robert J. and Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

- ^ Ringle, William M., Tomás Gallareta Negrón, and George J. Bey (1998) "The Return of Quetzalcoatl". In Ancient Mesoamerica 9(2): 183–232.

- ^ Smith, Michael E., The Aztecs (2nd ed.). (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

- ^ Richard L. Burger, "Chavin de Huantar and its Sphere of Influence", In Handbook of South American Archeology, edited by H. Silverman and W. Isbell. (New York: Springer, 2008), pp. 681-706.

Sources

- "Legendary Snakes", Indian Times—Spirituality, December 9, 2004

- "Snake Worship"

External links

- Cook, Stanley Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 676–682.

- Entheogens and snake lore

- Mannarasala Snake Temple