User:LemonYourAid/sandbox

| Part of a series on |

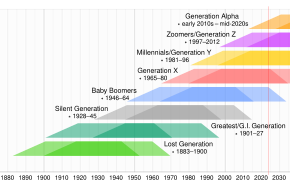

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

Generation Gender, Generation Z, or Gen Z for short, is the demographic cohort after the Millennials. Demographers and researchers typically use the mid- to late-1990s as starting birth years, while consensus has not been reached on the ending birth years. Members of Generation Z have used digital technology since a young age and are comfortable with the Internet and social media.

Terminology[edit]

In 2012, USA Today sponsored an online contest for readers to choose the name of the next generation after the Millennials. The name Generation Z was suggested. Some other names that were proposed included: iGeneration, Gen Tech, Gen Wii, Net Gen, Digital Natives, and Plurals.[1][2][3]

iGeneration (or iGen) is a name that several persons claim to have coined. Rapper MC Lars is credited with using the term as early as 2003.[4] Demographer Cheryl Russell claims to have first used the term in 2009.[1] Psychology professor and author Jean Twenge claims that the name iGen "just popped into her head" while she was driving near Silicon Valley, and that she had intended to use it as the title of her 2006 book Generation Me about the Millennial generation, until it was overridden by her publisher.[1]

Post-Millennial is a name given by the United States Department of Health and Human Services and the Pew Research Center in statistics published in 2016 showing the relative sizes and dates of the generations.[5] The same sources showed that, as of April 2016, the Millennial generation surpassed the population of Baby Boomers in the USA (77 million vs. 76 million in 2015 data);[6] however, the Post-Millennials were ahead of the Millennials in another Health and Human Services survey (69 million vs. 66 million).[7][citation needed]

In American slang, Generation Z may be referred to as Generation Snowflake. According to a 2016 article by Helen Rumbelow published in The Australian, "The term 'generation snowflake' started in the United States. Parents cherished their offspring as 'precious little snowflakes', each alike but unique, or 'everyone is special'."[8] Claire Fox argues recent parenting philosophy led to parenting methods which "denied resilience-building freedoms that past generations enjoyed".[9] The term "snowflake generation" was one of Collins Dictionary's 2016 words of the year. Collins defines the term as "the young adults of the 2010s, viewed as being less resilient and more prone to taking offence than previous generations."[10]

Statistics Canada has noted that the cohort is sometimes referred to as the Internet generation, as it is the first generation to have been born after the popularization of the Internet.[11]

In Japan, the cohort is described as Neo-Digital Natives, a step beyond the previous cohort described as Digital Natives. Digital Natives primarily communicate by text or voice, while neo-digital natives use video, video-telephony, and movies. This emphasizes the shift from PC to mobile and text to video among the neo-digital population.[12][13]

Date and age range definition[edit]

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines Generation Z as generation of people born in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[14] Oxford Living Dictionaries describes Generation Z as "the generation reaching adulthood in the second decade of the 21st century."[15]

The Pew Research Center defines the "Post-Millennials" as people born from 1997 onward, choosing this date for "different formative experiences," such as new technological developments and socioeconomic trends, including the widespread availability of wireless internet access and high-bandwidth cellular service, and key world events, including the September 11th terrorist attacks. Post-Millennials were no older than four years of age at the time of the attacks, and consequently had little to no memory of the event. Pew indicated they would use 1997–2012 for future publications but would remain open to date re-calibration.[16] According to this definition, the oldest member of Generation Z is 26–27 years old and the youngest is, or is turning, 11–12 years old in 2024.

Bloomberg News describes "Gen Z" as "the group of kids, teens and young adults roughly between the ages of 7 and 22" in 2019. In other words, for Bloomberg, Generation Z was born between 1997 and 2012.[17] The American Psychological Association starts Generation Z at 1997.[18][19] News outlets such as The Economist,[20] the Harvard Business Review,[21] Business Insider,[22] and The Wall Street Journal [23] describe Generation Z as people born since 1997.

Psychologist Jean Twenge and Sparks and Honey describe Generation Z as those born in 1995 or later.[24][25][26] Forbes stated that Generation Z is "composed of those born between 1995 and 2010."[27] In a 2018 report, Goldman Sachs describes "Gen-Z" as "today’s teenagers through 23-year olds."[28]

Australia's McCrindle Research Centre defines Generation Z as those born between 1995–2009, starting with a recorded rise in birth rates, and fitting their newer definition of a generational span with a maximum of 15 years.[29]

In Japan, generations are defined by a ten-year span with "Neo-Digital natives" beginning after 1996.[12][13]

Statistics Canada defines Generation Z as starting from the birth year 1993.[30] Statistics Canada does not recognize a traditional Millennials cohort and instead has Generation Z directly follow what it designates as Children of Baby Boomers.[31] Randstad Canada describes Generation Z as those born between 1995–2014.[32][33]

Characteristics[edit]

According to Forbes (2015) Generation Z is the cohort after the Millennials, defined as those born from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s. It comprises 25%[34][35] of the U.S. population, making the cohort more numerous than either Baby Boomers or Millennials.[34] Frank N. Magid Associates estimates that in the United States, 54% are caucasian, 24% are Hispanic, 14% are African-American, 4% are Asian, and 4% are multiracial or other.[36]

The Economist has described Generation Z as a more educated, well-behaved, stressed and depressed generation in comparison to previous ones.[37]

- Generation Z are often children of Generation X,[38][39][40] but they also have parents who are Millennials.[41] According to Public Relations Society of America, the Great Recession has taught Generation Z to be independent, and has led to an entrepreneurial desire, after seeing their parents and older siblings struggle in the workforce.[42]

- A 2013 survey by Ameritrade found that 47% in the United States (considered here to be those between the ages of 14 and 23) were concerned about student debt, while 36% were worried about being able to afford a college education at all.[43] This generation is faced with a growing income gap and a shrinking middle-class, which all have led to increasing stress levels in families.[44]

- Both the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Great Recession have greatly influenced the attitudes of this generation in the United States. However, unlike the older Millennials, Generation Z typically have no memories of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Since the oldest members were not yet cognizant when the 9/11 attacks occurred (or had not yet been born at that time), there is no generational memory of a time the United States has not been at war with the loosely defined forces of global terrorism.[45][46] Turner suggests it is likely that both events have resulted in a feeling of unsettlement and insecurity among the people of Generation Z with the environment in which they were being raised. The economic recession of 2008 is particularly important to historical events that have shaped Generation Z, due to the ways in which their childhoods may have been affected by the recession's financial stresses felt by their parents.[47]

- A 2016 U.S. study found that church attendance during young adulthood was 41% among Generation Z, compared to 18% for Millennials, 21% of Generation X, and 26% of the Baby Boomers when they were at the same age.[48] A 2016 survey by Barna and Impact 360 Institute on about 1,500 Americans aged 13 and up that the percent of atheists and agnostics was to 21% among Generation Z, compared to 15% for Millennials, 13% for Generation X, and 9% for Baby Boomers. Meanwhile, 59% of Generation Z were Christians (including Catholics), compared to 65% for the Millennials, 65% for Generation X, and 75% for the Baby Boomers. Researchers also asked over 600 non-Christian teenagers and almost 500 adults what their biggest barriers to faith were. They found that for Generation Z, these were what they perceived as internal contradictions of the religion and its believers, yet only six percent reported an unpleasant personal experience with a Christian or at church.[49] Globally, religion is in decline in North America and Western Europe, but is growing in the rest of the world.[50]

Gen Z is the most diverse generation to date. Adweek reported on a 2018 U.S. study on Generation Z, entitled Identity Shifters, which found that many Gen Z identify with multiple ethnic or racial identities. They also uniquely feel a pressure to play up, play down, or challenge what is expected of them, both in their personal and public lives.[51]

Arts and culture[edit]

A 2019 study conducted by the online rental platform Nestpick considered 110 cities worldwide with regards to factors they believed were important to Generation Z, such as social equality, multiculturalism, and digitalization, and found that overall, London, Stockholm, Los Angeles, Toronto, and New York City topped the list. However, the rankings changed with respect to each of the categories considered. Oslo, Bergen (both in Norway), Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmo (all from Sweden) were champions of gender equality, yet Seoul, London, Boston, Stockholm, and Los Angeles best met the digital wants of Generation Z. However, given that members of Generation Z tend to be financially pragmatic, all the aforementioned cities shared a common disadvantage: high costs of living. Therefore, the Nestpick index for Generation Z could change in the upcoming years as these people grow older and have different priorities.[52]

Generation Z can also be described as "the next creative class," with young artists, musicians, photographers, directors and influencers eagerly finding their voices in a new world of content creation, from Youtube and Instagram to any number of content sites.[53] Urban researcher Richard Florida and his team found, using U.S. Census data between 2005 and 2017, an increase in employment across the board for members of the "creative class" – people in education, healthcare, law, the arts, technology, science, and business, not all of whom have a university degree – in virtually all U.S. metropolitan areas with a population of a million or more. Indeed, the total number of the creative class grew from 44 million in 2005 to over 56 million in 2017. Florida suggested that this could be a "tipping point" in which talents head to places with a high quality of life yet lower costs of living than well-established creative centers, such as New York City and Los Angeles, what he called the "superstar cities."[54]

According to Girls Gen Z Digital media company Sweety High's 2018 Gen Z Music Consumption & Spending Report, Spotify ranked first for music listening among Gen Z, terrestrial radio ranked second, while YouTube was reported to be the preferred platform for music discovery.[55] Using artificial intelligence, Joan Serra and his team at the Spanish National Research Council studied the massive Million Song Dataset and found that between 1955 and 2010, popular music has gotten louder, while the chords, melodies, and types of sounds used have become increasingly homogenized. While the music industry has long been accused of producing songs that are louder and blander, this is the first time the quality of songs is comprehensively studied and measured.[56]

Education[edit]

In continental Europe[edit]

In Sweden, universities are tuition-free, as is the case in Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland. However, Swedish students typically graduate with a lot of debt due to the high cost of living in their country, especially in the large cities such as Stockholm. The ratio of debt to expected income after graduation for Swedes was about 80% in 2013. In the U.S., despite incessant talk of student debt reaching epic proportions, that number stood at 60%. Moreover, about seven out of eight Swedes graduate with debt, compared to one half in the U.S. In the 2008-9 academic year, virtually all Swedish students take advantage of state-sponsored financial aid packages from a government agency known as the Centrala Studiestödsnämnden (CSN), which include low-interest loans with long repayment schedules (25 years or until the student turns 60). In Sweden, student aid is based on their own earnings whereas in some other countries, such as Germany or the United States, such aid is premised on parental income as parents are expected to help foot the bill for their children's education. In the 2008-9 academic year, Australia, Austria, Japan, the Netherlands, and New Zealand saw an increase in both the average tuition fees of their public universities for full-time domestic students and the percentage of students taking advantage of state-sponsored student aid compared to 1995. In the United States, there was an increase in the former but not the latter.[57]

In 2005, judges in Karlsruhe, Germany, struck down a ban on university fees as unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the constitutional right of German states to regulate their own higher education systems. This ban was introduced in order to ensure equality of access to higher education regardless of socioeconomic class. Bavarian Science Minister Thomas Goppel told the Associated Press, "Fees will help to preserve the quality of universities." Supporters of fees argued that they would help ease the financial burden on universities and would incentivize students to study more efficiently, despite not covering the full cost of higher education, an average of €8,500 as of 2005. Opponents believed fees would make it more difficult for people to study and graduate on time.[58] Germany also suffered from a brain drain, as many bright researchers moved abroad while relatively few international students were interested in coming to Germany. This has led to the decline of German research institutions.[59]

In France, while year-long mandatory military service for men was abolished in 1996 by President Jacques Chirac, who wanted to build a professional all-volunteer military,[60] all citizens between 17 and 25 years of age must still participate in the Defense and Citizenship Day, when they are introduced to the French Armed Forces, and take language tests.[60] In 2019, President Emmanuel Macron introduced something similar to mandatory military service, but for teenagers, as promised during his presidential campaign. Known as the Service National Universel or SNU (fr:Service national universel), it is a compulsory civic service. While students will not have to shave their heads or handle military equipment, they will have to sleep in tents, get up early (at 6:30 am), participate in various physical activities, raise the tricolor, and sing the national anthem. They will have to wear a uniform, though it is more akin to the outfit of security guards rather than military personnel. This program takes a total of four weeks. In the first two, youths learn how to provide first aid, how navigating with a map, how to recognize fake news, emergency responses for various scenarios, and self-defense. In addition, they get health checks and get tested on their mastery of the French language, and they participate in debates on a variety of social issues, including environmentalism, state secularism, and gender equality. In the second fortnight, they volunteer with a charity for local government. The aim of this program is to promote national cohesion and patriotism, at a time of deep division on religious and political grounds, to get people out of their neighborhoods and regions, and mix people of different socioeconomic classes, something mandatory military service used to do. Supporters thought that teenagers rarely raise the national flag, spend too much time on their phones, and felt nostalgic for the era of compulsory military service, considered a rite of passage for young men and a tool of character-building. Critics argued that this program is inadequate, and would cost too much.[61] The SNU is projected to affect some 800,000 French citizens each year when it becomes mandatory for all aged 16 to 21 by 2026, at a cost of some €1.6 billion.[61] Another major concern is that it will overburden the French military, already stretched thin by counter-terrorism campaigns at home and abroad.[60] A 2015 IFOP poll revealed that 80% of the French people supported some kind of mandatory service, military, or civilian. At the same time, returning to conscription was also popular; supporters included 90% of the UMP party, 89% of the National Front (now the National Rally), 71% of the Socialist Party, and 67% of people aged 18 to 24. This poll was conducted after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks.[62]

In English-speaking countries[edit]

In 2017, almost half of Britons have received higher education by the age of 30. This is despite the fact that £9,000 worth of student fees were introduced in 2012. U.K. universities first introduced fees in autumn 1998 to address financial troubles and the fact that universities elsewhere charged tuition. Prime Minister Tony Blair introduced the goal of having half of young Britons having a university degree in 1999, though he missed the 2010 deadline. Demand for higher education in the United Kingdom remains strong, driven by the need for high-skilled workers from both the public and private sectors. There was, however, a widening gender gap. As of 2017, women were more likely to attend or have attended university than men, 55% to 43%, a 12% gap.[63]

In 2013, less than a third of American public schools have access to broadband Internet service, according to the non-profit EducationSuperHighway. By 2019, however, that number reached 99%. This has increased the frequency of digital learning.[64]

According to a Northeastern University Survey, 81% of Generation Z in the U.S. believes obtaining a college degree is necessary in achieving career goals.[65] As Generation Z enters high school, and they start preparing for college, a primary concern is paying for a college education without acquiring debt. Students report working hard in high school in hopes of earning scholarships and the hope that parents will pay the college costs not covered by scholarships. Students also report interest in ROTC programs as a means of covering college costs.[66] According to NeaToday, a publication by the National Education Association, two thirds of Gen Zers entering college are concerned about affording college. One third plan to rely on grants and scholarships and one quarter hope that their parents will cover the bulk of college costs. While the cost of attending college is incredibly high for most Gen Zers, according to NeaToday, 65% say the benefits of graduating college exceed the costs.[66]

Generation Z is revolutionizing the educational system in many aspects. Thanks in part to a rise in the popularity of entrepreneurship and advancements in technology, high schools and colleges across the globe are including entrepreneurship in their curriculum.[67] A 2018 study found that while Gen Z values education, their personal brand is seen as more important; successful Youtubers and social media influencers have shown that the right image can be central to success.[53]

Employment prospects and economic trends[edit]

In 2018, as the number of robots at work continued to increase, the global unemployment rate fell to 5.2%, the lowest in 38 years. Current trends suggest that developments in artificial intelligence and robotics will not result in mass unemployment but can actually create high-skilled jobs. However, in order to take advantage of this situation, one needs a culture and an education system that promote lifelong learning. Honing skills that machines have not yet mastered, such as teamwork and effective communication, will be crucial.[68][69]

Parents of Generation Z might have the image of their child's first business being a lemonade stand or car wash. While these are great first businesses, Generation Z now has access to social media platforms, website builders, 3D printers, and drop shipping platforms which provides them with additional opportunities to start a business at a young age. The internet has provided a store front for Generation Z to sell their ideas to people around the world without ever leaving their house.[70]

As technological progress continues, something that is made evident by the emergence of or breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, robotics, three-dimensional printing, nanotechnology, quantum computing, autonomous vehicles, among other fields, culminating in what economist Klaus Schwab calls the 'Fourth Industrial Revolution', the demand for innovative, well-educated, and highly skilled workers continues to rise, as do their incomes. Demand for low-pay and low-skilled workers, on the other hand, will continue to fall.[71]

By analyzing data from the United Nations and the Global Talent Competitive Index, KDM Engineering found that as of 2019, the top five countries for international high-skilled workers are Switzerland, Singapore, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Sweden. Factors taken into account included the ability to attract high-skilled foreign workers, business-friendliness, regulatory environment, the quality of education, and the standard of living. Switzerland is best at retaining talents due to its excellent quality of life. Singapore is home to a world-class environment for entrepreneurs. And the United States offers the most opportunity for growth due to the sheer size of its economy and the quality of higher education and training.[72] As of 2019, these are also some of the world's most competitive economies, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). In order to determine a country or territory's economic competitiveness, the WEF considers factors such as the trustworthiness of public institutions, the quality of infrastructure, macro-economic stability, the quality of healthcare, business dynamism, labor market efficiency, and innovation capacity.[73]

Asia[edit]

Statistics from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reveal that between 2014 and 2019, Japan's unemployment rate went from about 4% to 2.4% and China's from almost 4.5% to 3.8%. These are some of the lowest rates among the top economies.[74]

When he came to power in 1949, Mao Zedong vowed to abolish capitalism and social classes. 'Old money' ceased to exist in China as a result of a centrally planned economy. But that changed in the 1980s when Deng Xiaoping introduced economic reforms; the middle and upper classes have blossoming ever since. In fact, he considered getting rich to be "glorious." Chinese cities have morphed into major shopping centers. The number of billionaires (in U.S. dollars) in China is growing faster than anywhere else in the world, so much so that butler academies, whose students will serve the 'new rich', and finishing schools, whose students were born to rich parents, have been established. However, according to the World Bank, 27% of Chinese still live below the poverty line. The Chinese Central Government promised to end poverty by 2020. President Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign also cracks down on what he considered 'ostentatious displays of wealth'. Moreover, members of China's upper class must align themselves closely with the Communist Party. A number of young Chinese entrepreneurs have taken advantage of the Internet to become social media influencers to sell their products.[75]

Technology companies and startups are booming in China and Southeast Asia. Whereas in the past, Chinese firms copied the business strategies and models from their U.S. counterparts, now, they are developing their own approaches, and Southeast Asian companies are learning from their success and experience, a practice known as "Copy from China." E-commerce has been flourishing. In Singapore, for example, not only is it now possible to place orders online, one may also purchase groceries in person, pay by mobile phone, and have them packed by machines; there are no cashiers. Whereas Westerners were first introduced to the Internet via their personal computers, people in China and Southeast Asia first got online with their mobile phones. Consequently, the e-commerce industry's heavy usage of mobile phone applications has paid off handsomely. In particular, Chinese entrepreneurs invest in what are known as "super-apps," those that enable users to access all kinds of services within them, not just messaging, but also bike rentals and digital wallets. In Indonesia, relying on credit-card payments is difficult because the market penetration of this technology remains rather low (as of 2019). Nevertheless, e-commerce and ride-hailing are growing there, too. But it is Singapore that is the startup hub of the region, thanks to its excellent infrastructure, government support, and abundant capital. Furthermore, Singaporean technology firms are "uniquely positioned" to learn from both the U.S. and China.[76]

Europe[edit]

In Europe, although the unemployment rates of France and Italy remained relatively high, they were markedly lower than previously. Meanwhile, the German unemployment rate dipped below even that of the United States, a level not seen since its unification almost three decades prior.[74] Eurostat reported in 2019 that overall unemployment rate across the European Union dropped to its lowest level since January 2000, at 6.2% in August, meaning about 15.4 million people were out of a job. The Czech Republic (3%), Germany (3.1%) and Malta (3.3%) enjoyed the lowest levels of unemployment. Member states with the highest unemployment rates were Italy (9.5%), Spain (13.8%), and Greece (17%). Countries with higher unemployment rates compared to 2018 were Denmark (from 4.9% to 5%), Lithuania (6.1% to 6.6%), and Sweden (6.3% to 7.1%).[77]

According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), the European Union in the late 2010s suffers from shortages of STEM specialists (including ICT professionals), medical doctors, nurses, midwives and schoolteachers. However, the picture varies depending on the country. In Italy, environmentally friendly architecture is in high demand. Estonia and France are running short of legal professionals. Ireland, Luxembourg, Hungary, and the United Kingdom need more financial experts. All member states except Finland need more ICT specialists, and all but Belgium, Greece, Spain, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal and the United Kingdom need more teachers. The supply of STEM graduates has been insufficient because the dropout rate is high and because of an ongoing brain drain from some countries. Some countries need more teachers because many are retiring and need to be replaced. At the same time, Europe's aging population necessitates the expansion of the healthcare sector. Disincentives for (potential) workers in jobs in high demand include low social prestige, low salaries, and stressful work environments. Indeed, many have left the public sector for industry while some STEM graduates have taken non-STEM jobs.[78]

Even though pundits predicted that the uncertainty due to the Brexit referendum would cause the British economy to falter or even fall into a recession, the unemployment rate has dipped below 4% while real wages have risen slightly in the late 2010s, two percent as of 2019. In particular, medical doctors and dentists saw their earnings bumped above the inflation rate in July 2019. Despite the fact that the government promised to an increase in public spending (£13 billion, or 0.6% of GDP) in September 2019, public deficit continues to decline, as it has since 2010. Nevertheless, uncertainty surrounding Britain's international trade policy suppressed the chances of an export boom despite the depreciation of the pound sterling.[79] According to the employment website Glassdoor, the highest paying entry level jobs in the United Kingdom in 2019 are investment banking analyst, software engineer, business analyst, data scientist, financial analyst, software developer, civil engineer, audit assistant, design engineer, mechanical engineer. Their median base salaries range from about £28,000 to £51,000 a year. In general, people with STEM degrees have the best chances of being recruited into a high-paying job. According to the Office for National Statistics, the median income of the United Kingdom in 2018 was £29,588.[80]

North America[edit]

Between 2014 and 2019, Canada's overall unemployment rate fell from about 7% to below 6%, according to the IMF.[81] In 2017, the magazine Canadian Business analyzed publicly available data from Statistics Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada to determine the top occupations on the basis of growth and salaries. They included construction managers, mining and quarry managers, pilots and flying instructors, software engineers, police officers, firefighters, urban planners, petroleum, chemical, agricultural, biomedical, aerospace, and railroad engineers, business services managers, deck officers, corporate sales managers, pharmacists, elevator mechanics, lawyers, economic development directors, real-estate and financial managers, telecommunications managers, utilities managers, pipe-fitting managers, forestry managers, nurse practitioners, and public administration managers.[82] However, in the late 2010s, Canada's oil and gas industry has been in decline due to a lack of political support and unfavorable policies from Ottawa. The number of oil rigs in Western Canada, where most of the country's deposits are located, dropped from 900 in 2014 to 550 in 2019. Many Canadian companies have moved their crew and equipment to the United States, especially to Texas.[83]

According to the United States Department of Labor, the unemployment rate in September 2019 was 3.5%, a number not seen since December 1969.[84] At the same time, labor participation remained steady and most job growth tended to be full-time positions.[84] Economists generally consider a population with an unemployment rate lower than 4% to be fully employed. In fact, even people with disabilities or prison records are getting hired.[85] At the same time, wages continue to grow, especially for low-income earners.[85] On average, they grew by 2.7% in 2016 and 3.3% in 2018.[86] These developments ease fears of an upcoming recession.[87] Moreover, economists believe that job growth could slow to an average of just 100,000 per month and still be sufficient to keep up with population growth and keep economic recovery going.[86]

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the occupations with the highest median annual pay in the United States in 2018 included medical doctors (especially psychiatrists, anesthesiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, surgeons, and orthodontists), chief executives, dentists, information system managers, chief architects and engineers, pilots and flight engineers, petroleum engineers, and marketing managers. Their median annual pay ranged from about $134,000 (marketing managers) to over $208,000 (aforementioned medical specialties).[88] Meanwhile, the occupations with the fastest projected growth rate between 2018 and 2028 are solar cell and wind turbine technicians, healthcare and medical aides, cyber security experts, statisticians, speech-language pathologists, genetic counselors, mathematicians, operations research analysts, software engineers, forest fire inspectors and prevention specialists, post-secondary health instructors, and phlebotomists. Their projected growth rates are between 23% (medical assistants) and 63% (solar cell installers); their annual median pays range between roughly $24,000 (personal care aides) to over $108,000 (physician assistants).[89] Occupations with the highest projected numbers of jobs added between 2018 and 2028 are healthcare and personal aides, nurses, restaurant workers (including cooks and waiters), software developers, janitors and cleaners, medical assistants, construction workers, freight laborers, marketing researchers and analysts, management analysts, landscapers and groundskeepers, financial managers, tractor and truck drivers, and medical secretaries. The total numbers of jobs added ranges from 881,000 (personal care aides) to 96,400 (medical secretaries). Annual median pays range from over $24,000 (fast-food workers) to about $128,000 (financial managers).[90]

According to the Department of Education, people with technical or vocational trainings are slightly more likely to be employed than those with a bachelor's degree and significantly more likely to be employed in their fields of specialty.[91] The United States currently suffers from a shortage of skilled tradespeople.[91] If nothing is done, this problem will get worse as older workers retire and the market tightens due to falling unemployment rates. Economists argue that raising wages could incentivize more young people to pursue these careers. Many manufacturers are partnering with community colleges to create apprenticeship and training programs. However, they still have an image problem as people perceive manufacturing jobs as unstable, given the mass layoffs during the Great Recession of 2007-8.[92] After the Great Recession, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs reached a minimum of 11.5 million in February 2010. It rose to 12.8 million in September 2019. It was 14 million in March 2007.[93] As of 2019, manufacturing industries made up 12% of the U.S. economy, which is increasingly reliant on service industries, as is the case for other advanced economies around the world.[94] Nevertheless, twenty-first-century manufacturing is increasingly sophisticated, using advanced robotics, 3D printing, cloud computing, among other modern technologies, and technologically savvy employees are precisely who employers need. Four-year university degrees are unnecessary; technical or vocational training, or perhaps apprenticeships would do.[95]

South America[edit]

Unlike the other major economies, unemployment actually increased in Brazil, from about 6.7% in 2014 to about 11.4% in 2018. Although its economy remains growing, it is still recovering from a recession in 2015 and 2016. Wages have remained stagnant and the labor market has been weak.[74] Unemployment rose to 12.7% in March 2019, or about 13.4 million people. Underemployment also increased in the first quarter of 2019.[96]

Health issues[edit]

A 2015 study found that the frequency of nearsightedness has doubled in the United Kingdom within the last 50 years. Ophthalmologist Steve Schallhorn, chairman of the Optical Express International Medical Advisory Board, noted that research have pointed to a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain. The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm on a similar vein.[97] According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome, is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage. In order to alleviate or prevent eyestrain, the Vision Council recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray, increase text sizes, and blinking more often. Parents should not only limit their children's screen time but should also lead by example.[98]

A research article published in 2019 in the Lancet journal reported that the number of South Africans aged 15 to 19 being treated for HIV increased by a factor of ten between 2019 and 2010. This is partly due to improved detection and treatment programs. However, less than 50% of the people diagnosed with HIV went onto receive antiviral medication due to social stigma, concerns about clinical confidentiality, and domestic responsibilities. While the annual number of deaths worldwide due to HIV/AIDS has declined from its peak in the early 2000s, experts warned that this venereal disease could rebound if the world's booming adolescent population is left unprotected.[99]

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveal that 46% of Australians aged 18 to 24, about a million people, were overweight in 2017 and 2018. That number was 39% in 2014 and 2015. Obese individuals face higher risks of type II diabetes, heart disease, osteoarthritis and stroke. The Australian Medical Associated and Obesity Coalition have urged the federal government to levy a tax on sugary drinks, to require health ratings, and to regulate the advertisement of fast foods. In all, the number of Australian adults who are overweight or obese rose from 63% in 2014-15 to 67% in 2017-18.[100]

Political views[edit]

A 2017 survey produced by MTV and the Public Religion Research Institute found that 72% of Americans aged 15 to 24 held unfavorable views of President Donald Trump.[101][102] In a 2016 poll of Gen Z-aged students by the Hispanic Heritage Foundation, 32% of participants supported Donald Trump, while 22% supported Hillary Clinton with 31% declining to choose.[103] By contrast, in a 2016 mock election of upper elementary, middle, and high school students conducted by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump among the students, with Clinton receiving 46% of the vote, Donald Trump receiving 41%, and other candidates receiving 12%.[104]

In 2016, the Varkey Foundation and Populus conducted an international study examining the attitudes of Generation Z in twenty countries. Majorities of those surveyed supported same-sex marriage, transgender rights and gender equality.[105][106] However, a 2018 poll conducted by Harris on behalf of the LGBT advocacy group GLAAD found that despite being frequently described as the most tolerant segment of society, Americans aged 18 to 34—most Millennials and the oldest members of Generation Z—have become less accepting LGBT individuals compared to previous years. In 2016, 63% of Americans in that age group said they felt comfortable interacting with members of the LGBT community; that number dropped to 53% in 2017 and then to 45% in 2018. On top of that, more people reported discomfort learning that a family member was LGBT (from 29% in 2017 to 36% in 2018), having a child learning learning LGBT history (30% to 39%), or having an LGBT doctor (27% to 34%). Harris found that young women were driving this development.[107] Results from this Harris poll were released on the 50th anniversary of the riots that broke out in Stonewall Inn,[107] New York City, in June 1969, thought to be the start of the LGBT rights movement.[108] At that time, homosexuality was considered a mental illness or a crime in many U.S. states.[108]

Goldman Sachs analysts Robert Boroujerdi and Christopher Wolf describe Generation Z as "more conservative, more money-oriented, more entrepreneurial and pragmatic about money compared with Millennials".[109] 2018 surveys of teenagers 13 to 17 and adults aged 18 or over conducted by the Pew Research Center found that Generation Z had broadly similar views to the Millennials on various political and social issues. More specifically, 54% of Generation Z believed that climate change is real and is due to human activities. 70% wanted the government to play a more active role in solving their problems. 67% were indifferent towards pre-nuptial cohabitation. 49% considered single motherhood to be neither a positive or a negative for society. 62% saw increased ethnic or racial diversity as good for society. 48% approved of same-sex marriage, and 53% deemed interracial marriage to be a positive for society. In most cases, Generation Z and the Millennials tended hold quite different views from the Silent Generation, with the Baby Boomers and Generation X in between. In the case of financial responsibility in a two-parent household, though, majorities from across the generations answered that it should be shared, with 58% for the Silent Generation, 73% for the Baby Boomers, 78% for Generation X, and 79% for both the Millennials and Generation Z.[110]

According to the Hispanic Heritage Foundation, about eight out of ten members of Generation Z in the U.S. identify as "fiscal conservatives."[111] In 2018, the International Federation of Accountants released a report on a survey of 3,388 individuals aged 18 to 23 hailing from G20 countries, with a sample size of 150 to 300 per country. They found that members of Generation Z prefer a nationalist to a globalist approach to public policy by a clear margin, 51% to 32%. Nationalism was strongest in China (by a 44% margin), India (30%), South Africa (37%), and Russia (32%), while support for globalism was strongest in France (20% margin) and Germany (3%). In general, for members of Generation Z, the top three priorities for public policy are the stability of the national economy, the quality of education, and the availability of jobs; the bottom issues, on the other hand, were addressing income and wealth inequality, making regulations smarter and more effective, and improving the effectiveness of international taxation. Moreover, healthcare is a top priority for Generation Z in Canada, France, Germany, and the United States. Addressing climate change is very important for Generation Z in India, and South Korea, and tackling wealth and income inequality is of vital importance to the same in Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.[112]

In a study conducted in 2015 the Center for Generational Kinetics found that American Generation Zers, defined here as those born 1996 and onwards, are less optimistic about the state of the US economy than their generation predecessors, Millennials.[113] More recent research (2018) found that Gen Z are fearful of what staunch, divisive political stances have done to the world, and thus are hesitant to adopt hard political positions. They are more likely to say they are "leaning" or "tend to agree" with a political party, rather than claim membership, and feel that they are not as well-informed as they would like to be. Despite this feeling of a lack of sufficient knowledge, Generation Z believes it will right the wrongs of the world, putting great stock in the strength of their beliefs, which many feel alone will drive change.[53]

The March for Our Lives, a 2018 demonstration following the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting was described by CNBC as an indicator of the political power of Generation Z. Journalist Arick Wierson stated "politicians from both major parties should take note."[114] In March 2018, survivors of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, themselves members of Generation Z, started to refer to themselves as the mass shooting generation, though school shootings such as the Columbine High School massacre have also been associated with earlier generations.[115] An opinion piece titled "Dear National Rifle Association: We Won't Let You Win, From, Teenagers" published in March 2018 in The New York Times describes Generation Z as the generation after Millennials who will "not forget the elected officials who turned their backs on their duty to protect children."[116][117] However, according a field survey by The Washington Post interviewing every fifth person at the protest, only ten percent of the participants were 18 years of age or younger. Meanwhile, the adult participants of the protest had an average age of just under 49.[118] Polls conducted by Gallup and the Pew Research Center found that support for stricter gun laws among people aged 18 to 29 and 18 to 36, respectively, is statistically no different from that of the general population. According to Gallup, 57% of Americans are in favor of stronger gun control legislation.[119]

Psychographics[edit]

A 2014 study Generation Z Goes to College found that Generation Z students self-identify as being loyal, compassionate, thoughtful, open-minded, responsible, and determined.[120] How they see their Generation Z peers is quite different from their own self-identity. They view their peers as competitive, spontaneous, adventuresome, and curious—all characteristics that they do not see readily in themselves.[120] In addition, some authors consider that some of their competencies, such as reading competence, are being transformed due to their familiarity with digital devices, platforms and texts.[121]

Generation Z is generally more risk-averse in certain activities than earlier generations. In 2013, 66% of teenagers (older members of Generation Z) had tried alcohol, down from 82% in 1991. Also, in 2013, 8% of teenagers never or rarely wear a seat belt when riding in a car with someone else, as opposed to 26% in 1991.[122] Research from the Annie E. Casey Foundation conducted in 2016 found Generation Z youth had lower teen pregnancy rates, less substance abuse, and higher on-time high school graduation rates compared with Millennials. The researchers compared teens from 2008 and 2014 and found a 40% drop in teen pregnancy, a 38% drop in drug and alcohol abuse, and a 28% drop in the percentage of teens who did not graduate on time from high school.[123][124]

Generation Z appears to be more apprehensive about overtly sharing their beliefs, sensitive toward discourse in an increasingly public and politically polarized landscape.[53]

A 2018 U.S. research study, Identity Shifters, found that Generation Z is notably different in their partaking of "situational identities" – presenting the identity they think will be most relevant to the particular audience, platform or situation. With the influence of social media throughout their developmental stages, the study found Gen Z to exhibit a tendency to tailor their identity to context.[53] The research also identified nine cultural and societal shifts that characterize Generation Z:

- Traditional core identifiers (gender, sexuality, race, family) are increasingly being redefined and open to interpretation;

- Personal privacy is dwindling;

- Traditional hallmarks of adulthood – such as college completion, marriage, parenthood – are delayed or in flux;

- Chronological age attributes are more open to compression – behaving in ways traditionally associated with those much younger – or acceleration, with boys and girls feeling sexualized and making choices much earlier in life about gender, career, and social stances;

- Uncertainty about navigating the pathway to future financial security, causing feelings of freedom and also anxiety;

- A decline of mainstream pop culture due to the multiplicity of platforms and personalized content;

- The rise of micro-communities, based on social media connections;

- A shift to community-centered or collectivist attitude over "rugged individualism;" and

- The prioritization of emotions/emotional intelligence, and a premium on how one's actions make others feel.[53]

Use of technology and social media[edit]

Generation Z is the first cohort to have Internet technology readily available at a young age.[125] With the web revolution that occurred throughout the 1990s, they have been exposed to an unprecedented amount of technology in their upbringing, with the use of mobile devices growing exponentially over time. Anthony Turner characterizes Generation Z as having a 'digital bond to the Internet', and argues that it may help youth to escape from emotional and mental struggles they face offline.[47]

According to U.S. consultants Sparks and Honey in 2014, 41% of Generation Z spend more than three hours per day using computers for purposes other than schoolwork, compared with 22% in 2004.[126] In 2015, an estimated 150,000 apps, 10% of those in Apple's App Store, were educational and aimed at children up to college level,[127] though opinions are mixed as to whether the net result will be deeper involvement in learning[127] and more individualized instruction, or impairment through greater technology dependence[128] and a lack of self-regulation that may hinder child development.[128] Parents of Gen Z'ers fear the overuse of the Internet, and dislike the ease of access to inappropriate information and images, as well as social networking sites where children can gain access to people worldwide. Children reversely feel annoyed with their parents and complain about parents being overly controlling when it comes to their Internet usage.[129]

In a TEDxHouston talk, Jason Dorsey of the Center for Generational Kinetics stressed the notable differences in the way that Millennials and Generation Z consume technology, with 18% of Generation Z feeling that it is okay for a 13-year-old to have a smartphone, compared with just 4% for the previous generation.[130][131][132] An online newspaper about texting, SMS and MMS writes that teens own cellphones without necessarily needing them; that receiving a phone is considered a rite of passage in some countries, allowing the owner to be further connected with their peers, and it is now a social norm to have one at an early age.[133] An article from the Pew Research Center stated that "nearly three-quarters of teens have or have access to a smartphone and 30% have a basic phone, while just 12% of teens 13 to 15 say they have no cell phone of any type".[134] These numbers are only on the rise and the fact that the majority own a cell phone has become one of this generations defining characteristics. As a result of this "24% of teens go online 'almost constantly'".[134]

The use of social media has become integrated into the daily lives of most Gen Z'ers with access to mobile technology, who use it primarily to keep in contact with friends and family. As a result, mobile technology has caused online relationship development to become a new generational norm.[135] Gen Z uses social media and other sites to strengthen bonds with friends and to develop new ones. They interact with people who they otherwise would not have met in the real world, becoming a tool for identity creation.[129] The negative side to mobile devices for Generation Z, according to Twenge, is they are less "face to face", and thus feel more lonely and left out.[136]

Focus group testing found that while teens may be annoyed by many aspects of Facebook, they continue to use it because participation is important in terms of socializing with friends and peers. Twitter and Instagram are seen to be gaining popularity among members of Generation Z, with 24% (and growing) of teens with access to the Internet having Twitter accounts.[137] This is, in part, due to parents not typically using these social networking sites.[137] Snapchat is also seen to have gained attraction in Generation Z because videos, pictures, and messages send much faster on it than in regular messaging. Speed and reliability are important factors in members of Generation Z choice of social networking platform. This need for quick communication is presented in popular Generation Z apps like Vine and the prevalent use of emojis.[122]

A study by Gabrielle Borca, et al found that teenagers in 2012 were more likely to share different types of information than teenagers in 2006.[137] However, they will take steps to protect information that they do not want being shared, and are more likely to "follow" others on social media than "share".[120] A survey of U.S. teenagers from advertising agency J. Walter Thomson likewise found that the majority of teenagers are concerned about how their posting will be perceived by people or their friends. 72% of respondents said they were using social media on a daily basis, and 82% said they thought carefully about what they post on social media. Moreover, 43% said they had regrets about previous posts.[138] RPA research from 2018 put a sharper point on this, finding that Gen Z behavior evidences a hyper-aware, "curated" approach to expressing themselves online, with almost half of Gen Z respondents having one or more "Finstagram" (meaning "Fake Instagram") accounts, created to isolate their full identities while interacting with specific audiences. The research also found that Gen Z is more likely to trust social media sources and influencers when seeking answers (52%) over people they know personally (47%).[53]

Research conducted in 2017 reports that the social media usage patterns of this generation may be associated with loneliness, anxiety, and fragility, and that girls may be more affected than boys by social media. According to 2018 CDC reports, girls are disproportionately affected by the negative aspects of social media than boys.[139] Researchers at the University of Essex analyzed data from 10,000 families, from 2010-2015, assessing their mental health utilizing two perspectives: Happiness and Well-being throughout social, familial, and educational perspectives.[140] Within each family, they examined children who had grown from 10–15 during these years. At age 10, 10% of female subjects reported social media use, while this was only true for 7% of the male subjects. By age 15, this variation jumped to 53% for girls, and 41% for boys. This percentage influx may explain why more girls reported experiencing cyberbullying, decreased self-esteem, and emotional instability more than their male counterparts.

Other researchers hypothesize that girls are more affected by social media usage because of how they use it. In a study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2015, researchers discovered that while 78% girls reported to making a friend through social media, only 52% of boys could say the same.[141] However, boys are not explicitly less affected by this statistic. They also found that 57% of boys claimed to make friends through video gaming, while this was only true for 13% of girls.[141] Another Pew Research Center survey conducted in April 2015, reported that women are more likely to use Pinterest, Facebook, and Instagram than men. In counterpoint, men were more likely to utilize online forums, e-chat groups, and Reddit than women.[141]

Cyberbullying is more common now than among Millennials, the previous generation. It's more common among girls, 22% compared to 10% for boys. This results in young girls feeling more vulnerable to being excluded and undermined.[142][143]

Online dating[edit]

According to a national ethnology study by independent U.S. marketing and advertising agency RPA, 68% of Generation Z respondents currently or had previously used a dating website. The research also found that Gen Z tends to be cryptic when creating online dating profiles, and that despite their wide acceptance of dating platforms, their behavior is guarded: 78% of Gen Z profiles on Tinder do not specify the type of relationship being sought, and less than half stated something factual about the user, such as likes, interests or personality. Faces were partially concealed in 40% of profile photos, and 70% of user bios used only 20 words or less out of the allotted 75-word maximum.[53]

Successors[edit]

Matt Carmichael, former director of data strategy at Advertising Age, noted in 2015 that many groups were "competing to come up with the clever name" for the generation following Generation Z.[144] Mark McCrindle has suggested 'Generation Alpha', noting that scientific disciplines often move to the Greek alphabet after exhausting the Roman alphabet,[145][146] and 'Generation Glass', for the digital glass screens that have become the primary medium of content sharing.[145][146][147] McCrindle has predicted that this next generation will be "the most formally educated generation ever, the most technology-supplied generation ever, and globally the wealthiest generation ever."[145] McCrindle defined the term 'Generation Alpha' to be people born between 2011 and 2025.[148]

See also[edit]

- Cusper

- Generation gap

- Post-90s and Little Emperor Syndrome (China)

- Strawberry Generation (Taiwan)

- 9X Generation (Vietnam)

- List of generations

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Horovitz, Bruce (May 4, 2012). "After Gen X, Millennials, what should next generation be?". USA Today. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ Junco, Reynol; Mastrodicasa, Jeanna (2007). Connecting to the Net.Generation: What higher education professionals need to know about today's students. NASPA. ISBN 978-0-931654-48-0.

- ^ Homan, Audrey (October 27, 2015). "Z is for Generation Z". The Tarrant Institute for Innovative Education. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ https://www.ascap.com/playback/2005/winter/radar/mc_lars.aspx

- ^ "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research Center. Pew Research. April 25, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ "Projected Population by Generation". Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation. Pew Research. April 25, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ "Birth Under Each Generation". Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation. Pew Research. April 25, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Rumbelow, Helen (November 9, 2016). "Generation snowflake: Why millenials are mocked for being too delicate". The Australian. Surry Hills. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Fox, Claire (4 June 2016). "Generation Snowflake: how we train our kids to be censorious cry-babies". The Spectator. London. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016". Collins English Dictionary. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Generations in Canada". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ a b Thomas, Michael (April 19, 2011). Deconstructing Digital Natives: Young People, Technology, and the New Literacies. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-73900-2.

- ^ a b Takahashi, Toshie T. "Japanese Youth and Mobile Media". Rikkyo University. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ "Definition of Generation Z". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "generation z". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ "Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin". Pew Research Center. March 1, 2018.

- ^ Holman, Jordyn (April 25, 2019). "Millennials Tried to Kill the American Mall, But Gen Z Might Save It". Bloomberg. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ "Stress in America: Generation Z" (PDF). American Psychological Association. October 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Black Male Millennial: Unemployment and Mental Health" (PDF). American Psychological Association. August 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Generation Z is stressed, depressed and exam-obsessed". The Economist. February 2, 2019.

- ^ "A Survey of 19 Countries Shows How Generations X, Y, and Z Are — and Aren't — Different". The Harvard Business Review. August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Millennials love their brands, Gen Zs are terrified of college debt, and 6 other ways Gen Zs and millennials are totally different". Business Insider. February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Gen Z Is Coming to Your Office. Get Ready to Adapt". The Wall Street Journal. September 6, 2018.

- ^ "Smartphones raising a mentally fragile generation". eNCA.

- ^ "Reflection" (PDF). www.montreat.edu. 2018.

- ^ Oster, Erik (August 21, 2014). "This Gen Z Infographic Can Help Marketers Get Wise to the Future Here come the social natives". Adweek. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ "8 Ways Generation Z Will Differ From Millennials In The Workplace". Forbes. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ "Millennials and Gen Z Picking Their Wardrobes Online". Goldman Sachs. September 17, 2018.

- ^ Generations Defined. Mark McCrindle

- ^ "The Generation Z effect". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Generations in Canada". Statistics Canada. 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "How to attract and engage Millenials [sic]: Gen Y + Gen Z". RandstadCanada. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ "managing Gen Y and Z in the workplace". Randstad USA. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Dill, Kathryn (November 6, 2015). "7 Things Employers Should Know About The Gen Z Workforce". Forbes. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "A Look Into the Minds of Generation Z Consumers". The Atlas Business Journal. December 29, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ Frank N. Magid Associates. "The First Generation of the Twenty First Century." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 30 April 2012

- ^ "Generation Z is stressed, depressed and exam-obsessed". The Economist. February 27, 2019. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Williams, Alex (September 18, 2015). "Move Over, Millennials, Here Comes Generation Z". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ Beltramini, Elizabeth (October 2014). "Gen Z: Unlike the Generation Before". Associations of College Unions International. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ Jenkins, Ryan (June 9, 2015). "15 Aspects That Highlight How Generation Z Is Different From Millennials". Business2Community. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Quigley, Mary (July 7, 2016). "The Scoop on Millennials' Offspring — Gen Z". AARP. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Dupont, Stephen (December 10, 2015). "Move Over Millennials, Here Comes Generation Z: Understanding the 'New Realists' Who Are Building the Future". Public Relations Tactics. Public Relations Society of America.

- ^ Henderson, J Maureen (July 31, 2013). "Move Over, Millennials: Why 20-Somethings Should Fear Teens". Forbes. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ Turner, Anthony (June 1, 2015). "Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest". Journal of Individual Psychology. 71 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1353/jip.2015.0021.

- ^ "Column: High-maintenance Generation Z heads to work". USATODAY.COM. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Palmer, Alun (August 1, 2014). "Are you X, Y, Z, Boomer or Silent Generation – what does it mean for you?".

- ^ a b Turner, Anthony (2015). "Generation Z: Technology And Social Interest". Journal of Individual Psychology. 71 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1353/jip.2015.0021.

- ^ Hope, J (2016). "Get your campus ready for Generation Z". Dean & Provost. 17 (8): 1–7. doi:10.1002/dap.30174.

- ^ "Atheism Doubles Among Generation Z". Barna.com. Barna Group. January 24, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sherwood, Harriet (August 27, 2018). "Religion: why faith is becoming more and more popular". The Guardian. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Stanley, T.L. (May 7, 2019). "RPAs Study on Gen Z and Creativity Yields Key Takeaways for Marketers". Adweek.com. Adweek LLC. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Collie, Meghan (September 5, 2019). "Toronto is the 4th best city in the world for Gen Z. But can they afford it?". Global News. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Identity Shifters: Gen Z Exploration | RPA Marketing Report" (PDF). identityshifters.rpa.com. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Florida, Richard (July 9, 2019). "Maps Reveal Where the Creative Class Is Growing". CityLab. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Hodak, Brittany. "New Study Spotlights Gen Z's Unique Music Consumption Habits". Forbes. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Wickham, Chris (July 26, 2012). "Pop music too loud and all sounds the same: official". Reuters. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ Philips, Matt (May 31, 2013). "The High Price of a Free College Education in Sweden". Global. The Atlantic. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ "German Court Lifts Ban on Student Fees". Germany. DW. January 26, 2005. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ "Promoting Brain Gain for German Universities". Germany. DW. April 16, 2004. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Davies, Pascale (June 27, 2018). "On Macron's orders: France will bring back compulsory national service". France. EuroNews. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Villeminot, Florence (July 11, 2019). "National civic service: A crash course in self-defence, emergency responses and French values". French Connection. France 24. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Poll says 80% of French want a return to national service". France 24. January 26, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Adams, Richard (September 28, 2017). "Almost half of all young people in England go on to higher education". Higher Education. The Guardian. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ Mathewson, Tara Garcia (October 23, 2019). "Nearly all American classrooms can now connect to high-speed internet, effectively closing the "connectivity divide"". Future of Learning. Hechinger Report. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ "'Generation Z' is entrepreneurial, wants to chart its own future | news @ Northeastern". www.northeastern.edu. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Hawkins, B. Denise (July 13, 2015). "Here Comes Generation Z. What Makes Them Tick?". NEA Today. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "'Generation Z' is entrepreneurial, wants to chart its own future". news.northeastern.edu.

- ^ Kasriel, Stephane (January 10, 2019). "What the next 20 years will mean for jobs – and how to prepare". World Economic Forum. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Zao-Sanders, Marc; Palmer, Kelly (September 26, 2019). "Why Even New Grads Need to Reskill for the Future". Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business School Publishing. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Can a kid start a business?". Entrepreneur School. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus (January 14, 2016). "The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond". World Economic Forum. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Desjardins, Jeff (March 20, 2019). "Which countries are best at attracting high-skilled workers?". World Economic Forum. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Geiger, Thierry; Crotti, Roberto (October 9, 2019). "These are the world's 10 most competitive economies in 2019". World Economic Forum. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Edmond, Charlotte (June 12, 2019). "Unemployment is down across the world's largest economies". World Economic Forum. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Yu, Katrina (September 29, 2019). "China is producing billionaires faster than any other nation". PBS Newshour. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Soo, Zen (October 26, 2018). "From supermarkets to super apps, Southeast Asian tech start-ups are looking to China not Silicon Valley". South China Morning Post. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "EU unemployment drops to lowest level in nearly two decades: Eurostat". Euronews. October 1, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Skill shortages in Europe: Which occupations are in demand – and why". Cedefop. October 25, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Britain's economy is holding up well—for now". Britain. The Economist. October 31, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Chloe (July 24, 2019). "These are the highest paying entry level jobs in the UK". Work. CNBC. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Edmond, Charlotte (June 12, 2019). "Unemployment is down across the world's largest economies". World Economic Forum. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ "Canada's Best Jobs 2017: The Top 25 Jobs in Canada". Jobs. Maclean's. May 29, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Bakx, Kyle (October 30, 2019). "'It's the smart thing to do': Canadian oil driller moves all its rigs to the U.S." Business. CBC News. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Cox, Jeff (October 4, 2019). "September unemployment rate falls to 3.5%, a 50-year low, as payrolls rise by 136,000". CNBC. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Gogoi, Pallavi (May 20, 2019). "America Is In Full Employment, So Why Aren't We Celebrating?". NPR. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Newman, Rick (July 8, 2019). "Trump vs. Obama on jobs". Yahoo Finance. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Herron, Janna; Davidson, Paul (July 5, 2019). "June jobs report: Economy adds 224,000 jobs, easing recession fears". USA Today. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Occupational Handbook Outlook: Highest Paying Occupations". Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. September 4, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Occupational Outlook Handbook: Fastest Growing Occupations". Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. September 4, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Occupational Handbook Outlook: Most New Jobs". Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. September 4, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Krupnick, Matt (August 29, 2017). "After decades of pushing bachelor's degrees, U.S. needs more tradespeople". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Frazee, Gretchen (November 16, 2018). "Manufacturers say their worker shortage is getting worse. Here's why". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Horsley, Scott (October 4, 2019). "Hiring Steady As Employers Add 136,000 Jobs; Unemployment Dips To 3.5%". NPR. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "US unemployment rate falls to 50-year low of 3.5%". BBC News. October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Mindlin, Alan (October 30, 2019). "Gen Z Is the Answer to the Skills Gap— They Just Don't Know It Yet". Talent. Industry Week. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ McGeever, John (April 30, 2019). "UPDATE 1-Brazil's unemployment rate rises to 12.7%, reflects weak labor market". Reuters. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Stevens, Heidi (July 16, 2015). "Too much screen time could be damaging kids' eyesight". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Hellmich, Nanci (January 25, 2014). "Digital device use leads to eye strain, even in kids". USA Today. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ "10-fold surge in South Africa teens treated for HIV: Study". Channel News Asia. October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ McCauley, Dana (September 30, 2019). "Almost half young adults now overweight or obese, new ABS data shows". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Vandermaas-Peeler, Alex; Cox, Daniel; Fisch-Friedman, Molly; Jones, Robert P. (January 10, 2018). "Diversity, Division, Discrimination: The State of Young America | MTV/PRRI Report". Public Religion Research Institute. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Scott, Eugene (January 11, 2018). "The state of America, according to Generation Z". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "50k 'Gen Z' Students Identify as Republican – Hispanic Heritage Foundation". hispanicheritage.org. October 27, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ "America's Youth Have Spoken: Hillary Clinton Is Generation Z's Choice for President". Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Weale, Sally (February 8, 2017). "UK second only to Japan for young people's poor mental wellbeing". The Guardian. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Generation Z: Global Citizenship Survey" (PDF). Varkey Foundation. February 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Miller, Susan (June 24, 2019). "The young are regarded as the most tolerant generation. That's why results of this LGBTQ survey are 'alarming'". Nation. USA Today. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Miller, Susan (June 5, 2019). "Stonewall Forever: 50 years after the raid that sparked the LGBTQ movement, monument goes digital". USA Today. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ "Goldman Sachs chart of the generations". Business Insider. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Generation Z Looks a Lot Like Millennials on Key Social and Political Issues | Pew Research Center". January 17, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Conservative or Liberal? For Generation Z, It's Not That Simple". Huffington Post. October 20, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Identifying What Matters Most to the Next Generation" (PDF). International Federation of Accountants. 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Infographic: Gen Z Voter and Political Views Election 2016". The Center for Generational Kinetics.

- ^ Wierson, Arick (March 23, 2018). "March for our Lives gun control rally only hints at the political power of Generation Z". CNBC. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ CBSNews (March 19, 2018). "Parkland shooting survivors say the NRA is "basically threatening" them". Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Anapol, Avery (March 14, 2018). "NJ student march organizers pen op-ed to NRA We Wont Let You Win". The Hill. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ "Dear National Rifle Association: We Won't Let You Win. From, Teenagers". New York Times. March 13, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Fisher, Dana (March 28, 2018). "Here's who actually attended the March for Our Lives. (No, it wasn't mostly young people.)". Washington Post. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "Millennials Are No More Liberal On Gun Control Than Elders, Polls Show". NPR. February 24, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c Seemiller, Corey (2016). Generation Z Goes to College. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-1-119-14345-1.

- ^ Amiama-Espaillat, Cristina; Mayor-Ruiz, Cristina (2017). "Digital Reading and Reading Competence – The influence in the Z Generation from the Dominican Republic". Comunicar (in Spanish). 25 (52): 105–114. doi:10.3916/c52-2017-10. ISSN 1134-3478.

- ^ a b Williams, Alex (September 18, 2015). "Move Over, Millennials, Here Comes Generation Z". New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Generation Z Breaks Records in Education and Health Despite Growing Economic Instability of Their Families". PR Newswire. June 21, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ Blad, Evie (June 21, 2016). "Teenagers' Health, Educational Outcomes Improving, Report Finds". Education Week. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ Prensky, Marc (2001). "Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1". On the Horizon.

- ^ "Meet Generation Z: Forget Everything You Learned About Millennials". Sparks and Honey. June 17, 2014. p. 39. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "Should CellPhones Be Allowed in School?". education.cu-portland.edu. November 9, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ a b "Mobile and interactive media use by young children: The good, the bad and the unknown". EurekAlert!. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Borca, Gabriella; Bina, Manuela; Keller, Peggy S.; Gilbert, Lauren R.; Begotti, Tatiana (November 1, 2015). "Internet use and developmental tasks: Adolescents' point of view". Computers in Human Behavior. 52: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.029.

- ^ "Jason Dorsey TEDx Talk On Generation After Millennials: iGen Gen Z". Jason Dorsey. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ TEDx Talks (November 18, 2015), What do we know about the generation after millennials? | Jason Dorsey | TEDxHouston, retrieved April 6, 2016

- ^ Dorsey, Jason (2016). "iGen Tech Disruption" (PDF). Center for Generational Kinetics. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Regine (28 March 2005). "Owning a cell phone is rite of passage for teenagers". Textuality.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ a b Lenhart, Amanda (April 8, 2015). "Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center Internet Science Tech RSS. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Borca. "Internet Use".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Inc., MTR at CareerPlanner.com. "The Generations - Which Generation are You?". www.careerplanner.com.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c Madden, Mary; et al. (May 21, 2013). "Teens, Social Media, and Privacy". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ J. Walter Thompson. "CONSUMER INSIGHTS, J. WALTER THOMPSON INTELLIGENCE Meet Generation Z". Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at: cdc.gov/yrbs.

- ^ Booker, Cara L.; Kelly, Yvonne J.; Sacker, Amanda (March 20, 2018). "Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10-15 year olds in the UK". BMC Public Health. 18 (1): 321. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5220-4. PMC 5859512. PMID 29554883.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c "Men catch up with women on overall social media use". Pew Research Center. August 28, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ "Smartphones and Social Media". Child Mind Institute.

- ^ Twenge, Jean (August 22, 2017). IGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy--and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood--and What That Means for the Rest of Us.

- ^ Vanderkam, Laura (August 10, 2015). "What comes after Generation Z?". Fortune. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c Williams, Alex (September 19, 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Sterbenz, Christina (December 6, 2015). "Here's who comes after Generation Z – and they're going to change the world forever". Business Insider. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ McCrindle, Mark (2010). The ABC of XYZ. Australia: University of New South Wales. ISBN 978-1-74223-035-1.

- ^ Theko, Khumo. "Meet Generation Alpha". Flux Trends. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links[edit]

- The Downside of Diversity. Michael Jonas. The New York Times. August 5, 2007.

- The Next America: Modern Family. Pew Research Center. April 30, 2014. (Video, 2:16)

- Meet Generation Z: Forget Everything You Learned About Millennials – 2014 presentation by Sparks and Honey

- Is a University Degree a Waste of Money? CBC News: The National. March 1, 2017. (Video, 14:39)

- Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins – 2019 blog post by Michael Dimock