Bitcoin: Difference between revisions

→Background: Secondary RS instead of primary source |

|||

| Line 165: | Line 165: | ||

{{Main|History of bitcoin}} |

{{Main|History of bitcoin}} |

||

===Background=== |

===Background=== |

||

Before bitcoin, several [[digital cash|digital cash technologies]] were released, starting with the issuer-based [[ecash]] protocols of [[David Chaum]].<ref name=Narayanan2017/> The idea that solutions to computational puzzles could have some value was first proposed by cryptographers [[Cynthia Dwork]] and [[Moni Naor]] in 1992.<ref name=Narayanan2017/> The concept was [[Multiple discovery|independently rediscovered]] by [[Adam Back]] who developed [[hashcash]], a [[proof-of-work]] scheme for [[Anti-spam techniques|spam control]] in 1997.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction|last1=Narayanan|first1=Arvind|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=2016|isbn=978-0-691-17169-2|location=Princeton and Oxford|last2=Bonneau|first2=Joseph|last3=Felten|first3=Edward|last4=Miller|first4=Andrew|last5=Goldfeder|first5=Steven}}</ref> The first proposals for distributed digital scarcity-based [[cryptocurrencies]] came from [[cypherpunk|cypherpunks]] [[Wei Dai]] (b-money) and [[Nick Szabo]] ([[bit gold]]).<ref name="TsoSch2015">{{cite web | url = http://eprint.iacr.org/2015/464.pdf | first1 = Florian | last1 = Tsorsch | first2 = Bjorn | last2 = Scheuermann | title = Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey of Decentralized Digital Currencies | date = 15 May 2015 | access-date = 24 June 2015 }}</ref> In 2004, [[Hal Finney (cypherpunk)|Hal Finney]] developed [[Proof of work#Reusable proof-of-work|reusable proof of work]] using [[hashcash]] as its proof-of-work algorithm.<ref>{{cite |

Before bitcoin, several [[digital cash|digital cash technologies]] were released, starting with the issuer-based [[ecash]] protocols of [[David Chaum]].<ref name=Narayanan2017/> The idea that solutions to computational puzzles could have some value was first proposed by cryptographers [[Cynthia Dwork]] and [[Moni Naor]] in 1992.<ref name=Narayanan2017/> The concept was [[Multiple discovery|independently rediscovered]] by [[Adam Back]] who developed [[hashcash]], a [[proof-of-work]] scheme for [[Anti-spam techniques|spam control]] in 1997.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction|last1=Narayanan|first1=Arvind|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=2016|isbn=978-0-691-17169-2|location=Princeton and Oxford|last2=Bonneau|first2=Joseph|last3=Felten|first3=Edward|last4=Miller|first4=Andrew|last5=Goldfeder|first5=Steven}}</ref> The first proposals for distributed digital scarcity-based [[cryptocurrencies]] came from [[cypherpunk|cypherpunks]] [[Wei Dai]] (b-money) and [[Nick Szabo]] ([[bit gold]]).<ref name="TsoSch2015">{{cite web | url = http://eprint.iacr.org/2015/464.pdf | first1 = Florian | last1 = Tsorsch | first2 = Bjorn | last2 = Scheuermann | title = Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey of Decentralized Digital Currencies | date = 15 May 2015 | access-date = 24 June 2015 }}</ref> In 2004, [[Hal Finney (cypherpunk)|Hal Finney]] developed [[Proof of work#Reusable proof-of-work|reusable proof of work]] using [[hashcash]] as its proof-of-work algorithm.<ref>{{cite book |last=Judmayer |first=Aljosha |chapter=History of Cryptographic Currencies |date=2017 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-02352-1_3 |title=Blocks and Chains |pages=15–18 |publisher=[[Springer Nature|Springer]] |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-02352-1_3 |isbn=978-3-031-01224-2 |last2=Stifter |first2=Nicholas |last3=Krombholz |first3=Katharina |last4=Weippl |first4=Edgar|url=https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-02352-1}}</ref> These various attempts were not successful:<ref name=Narayanan2017/> Chaum's concept required centralized control and no banks wanted to sign on, hashcash had no protection against [[double-spending]], while b-money and bit gold were not resistant to [[Sybil attack]]s.<ref name=Narayanan2017>{{Cite journal |last=Narayanan |first=Arvind |last2=Clark |first2=Jeremy |date=2017-11-27 |title=Bitcoin's academic pedigree |url=https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=3136559 |journal=[[Communications of the ACM]] |volume=60 |issue=12 |pages=36–45 |doi=10.1145/3132259 |issn=0001-0782}}</ref> |

||

===Creation=== |

===Creation=== |

||

Revision as of 13:49, 22 November 2023

Official logo of Bitcoin | |

| Denominations | |

|---|---|

| Plural | Bitcoins |

| Symbol | ₿ (Unicode: U+20BF ₿ BITCOIN SIGN)[1] |

| Code | BTC,[a] XBT[b] |

| Precision | 10−8 |

| Subunits | |

| 1⁄1000 | Millibitcoin |

| 1⁄1000000 | Microbitcoin |

| 1⁄100000000 | Satoshi[2] |

| Development | |

| Original author(s) | Satoshi Nakamoto |

| White paper | "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" |

| Implementation(s) | Bitcoin Core |

| Initial release | 0.1.0 / 9 January 2009 |

| Latest release | 25.1 / 19 October 2023[3] |

| Code repository | github |

| Development status | Active |

| Written in | C++ |

| Source model | Free and open-source software |

| License | MIT License |

| Ledger | |

| Ledger start | 3 January 2009 |

| Timestamping scheme | Proof-of-work (partial hash inversion) |

| Hash function | SHA-256 (two rounds) |

| Issuance schedule | Decentralized (block reward) Initially ₿50 per block, halved every 210,000 blocks[4] |

| Block reward | ₿6.25 (As of 2023) |

| Block time | 10 minutes |

| Circulating supply | ₿18,925,000 (As of 10 January 2022) |

| Supply limit | ₿21,000,000[c] |

| Valuation | |

| Exchange rate | Floating |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | El Salvador[5] |

| Website | |

| Website | bitcoin |

Bitcoin (abbreviation: BTC[a] or XBT;[b] sign: ₿) is a decentralized cryptocurrency. Nodes in the bitcoin network verify transactions through cryptography and record them in a public distributed ledger called a blockchain. Based on a free market ideology, bitcoin was invented in 2008 by Satoshi Nakamoto, an unknown person.[6]

Use of bitcoin as a currency began in 2009,[7] with the release of its open-source implementation.[8]: ch. 1 In 2021, El Salvador adopted it as legal tender. Still, bitcoin is rarely used for transactions with merchants and is mostly seen as an investment. For this reason, it has been widely described as an economic bubble.[9]

As bitcoin is pseudonymous, its use by criminals has attracted the attention of regulators, leading to its ban by 51 countries as of 2021[update].[10] The environmental effects of bitcoin are also substantial.[11] Its proof-of-work algorithm for bitcoin mining is computationally difficult and requires increasing quantities of electricity,[12] so that, as of 2022[update], bitcoin is estimated to be responsible for 0.2% of world greenhouse gas emissions.[13]

Design

Units and divisibility

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is the bitcoin. Currency codes for representing bitcoin are BTC[a] and XBT.[b][17]: 2 Its Unicode character is ₿.[1] One bitcoin is divisible to eight decimal places.[8]: ch. 5 Units for smaller amounts of bitcoin are the millibitcoin (mBTC), equal to 1⁄1000 bitcoin, and the satoshi (sat), which is the smallest possible division, and named in homage to bitcoin's creator, representing 1⁄100000000 (one hundred millionth) bitcoin.[2] 100,000 satoshis are one mBTC.[18]

No uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization exists; some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, for the unit of account.[19] The Oxford English Dictionary advocates the use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases.[20]

Blockchain

The bitcoin blockchain is a public ledger that records bitcoin transactions.[21] It is implemented as a chain of blocks. Each block contains a SHA-256 cryptographic hash of the previous block,[21] linking them and giving the blockchain its name.[8]: ch. 7 [21] A network of communicating nodes running bitcoin software maintains the blockchain.[22]: 215–219 Transactions of the form payer X sends Y bitcoins to payee Z are broadcast to this network using readily available software applications.[citation needed] Individual blocks, public addresses, and transactions within blocks can be examined using a blockchain explorer.[23]

Network nodes can validate transactions, add them to their copy of the ledger, and then broadcast them to other nodes. To achieve independent verification of the chain of ownership, each network node stores its own copy of the blockchain.[24] Every 10 minutes on average, a new group of accepted transactions, called a block, is created, added to the blockchain, and quickly published to all nodes, without requiring central oversight. This allows bitcoin software to determine when a particular bitcoin was spent, which is needed to prevent double-spending. A conventional ledger records the transfers of actual bills or promissory notes that exist apart from it, but as a digital ledger, bitcoins only exist by virtue of the blockchain; they are represented by the unspent outputs of transactions.[8]: ch. 5

Transactions

Transactions are defined using a Forth-like scripting language.[8]: ch. 5 Transactions consist of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. When a user sends bitcoins, they designate each address and the amount of bitcoin being sent to that address in an output, allowing users to send bitcoins to multiple recipients in one transaction. To prevent double-spending, each input must refer to a previous unspent output in the blockchain.[25] The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer.[25] Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.[25]

The blocks in the blockchain were originally limited to 32 megabytes in size. The block size limit of one megabyte was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2010.[26] [citation needed] Eventually, the block size limit of one megabyte created problems for transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions.[27] Andreas Antonopoulos has stated Lightning Network is a potential scaling solution and referred to lightning as a second-layer routing network.[8]: ch. 8

Ownership

In the blockchain, bitcoins are linked to specific addresses that are hashes of a public key. Creating an address involves generating a random private key and then computing the corresponding address. This process is almost instant, but the reverse–finding the private key for a given address–is nearly impossible.[8]: ch. 4 Publishing a bitcoin address does not risk its private key, and it is extremely unlikely to accidentally generate a used key with funds. To use bitcoins, owners need their private key to digitally sign transactions, which are verified by the network using the public key, keeping the private key secret.[8]: ch. 5

Losing a private key means losing access to the bitcoins, with no other proof of ownership accepted by the network.[22] For instance, in 2013, a user lost ₿7,500, valued at $7.5 million, by accidentally discarding a hard drive with the private key.[28] It is estimated that around 20% of all bitcoins, worth about $20 billion in July 2018, are lost.[29]

To ensure the security of bitcoins, the private key must be kept secret.[8]: ch. 10 Exposure of the private key, such as through a data breach, can lead to theft of the associated bitcoins.[30] As of December 2017[update], approximately ₿980,000 had been stolen from cryptocurrency exchanges.[31]

Mining and supply

Mining is a record-keeping service done through the use of computer processing power. Miners keep the blockchain consistent, complete, and unalterable by repeatedly grouping newly broadcast transactions into a block, which is then broadcast to the network and verified by recipient nodes.[21]

To be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a proof-of-work (PoW).[21] The PoW requires miners to find a number called a nonce (a number used just once), such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target.[8]: ch. 8 This PoW is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate. Miners must try many different nonce values before a result happens to be less than the difficulty target. Because the difficulty target is extremely small compared to a typical SHA-256 hash, block hashes have many leading zeros[8]: ch. 8 as can be seen in this example block hash:

- 0000000000000000000590fc0f3eba193a278534220b2b37e9849e1a770ca959

By adjusting this difficulty target, the amount of work needed to generate a block can be changed. Every 2,016 blocks (approximately two weeks), nodes deterministically adjust the difficulty target to keep the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network.[8]: ch. 8 [33] As of April 2022[update], it takes on average 122 sextillion (122 thousand billion billion) attempts to generate a block hash smaller than the difficulty target.[citation needed] Computations of this magnitude are extremely expensive and utilize specialized hardware.[34]

The successful miner finding the new block is allowed to collect for themselves all transaction fees from transactions they included in the block, as well as a predetermined reward of newly created bitcoins.[35] To claim this reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included in the block, with the miner as the payee. All bitcoins in existence have been created through this type of transaction.[8]: ch. 8 This reward is reduced by half every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years), until ₿21 million[c] are generated. Under this schedule, new bitcoin issuance will halt around the year 2140. After that, miners would be rewarded by transaction fees only.[36] Though transaction fees are optional, miners can choose which transactions to process and prioritize those that pay higher fees.[25] Miners may choose transactions based on the fee paid relative to their storage size, not the absolute amount of money paid as a fee. These fees are generally measured in satoshis per byte (sat/b). The size of transactions is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction and the number of outputs.[8]: ch. 8

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications to the blockchain extremely hard, as an attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted.[37] As new blocks are being generated continuously, the difficulty of modifying an old block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases.[21]

Decentralization

Bitcoin is decentralized due to its lack of a central authority and of a single administrator.[4] Anybody can store the ledger on a computer,[8]: ch. 1 which is maintained by a network of equally privileged miners.[8]: ch. 1 Anybody can create a new bitcoin address without needing any approval.[8]: ch. 1 The issuance of bitcoins is decentralized, in that they are issued as a reward for the creation of a new block.[35]

Conversely, researchers have pointed out a "trend towards centralization". Although bitcoin can be sent directly from user to user, in practice intermediaries are widely used.[22]: 220–222 Bitcoin miners join large mining pools to minimize the variance of their income.[22]: 215, 219–222 [38]: 3 Because transactions on the network are confirmed by miners, decentralization of the network requires that no single miner or mining pool obtains 51% of the hashing power, which would allow them to double-spend coins, prevent certain transactions from being verified and prevent other miners from earning income.[39] As of 2013[update] just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power.[39] In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped its hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network.[40] According to Capkun & Capkun, writing for IEEE Security & Privacy, other parts of the ecosystem are also "controlled by a small set of entities", notably the maintenance of the client software, online wallets, and simplified payment verification (SPV) clients.[39]

Privacy and fungibility

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses.[41] Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.[42] To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction.[43]

While the Bitcoin network treats each bitcoin the same, thus establishing the basic level of fungibility, applications and individuals who use the network are free to break that principle. For instance, wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins equally, none is different from another. Still, the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that can allow users of chain analysis to refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions.[44] For example, in 2012, Mt. Gox froze accounts of users who deposited bitcoins that were known to have just been stolen.[45]

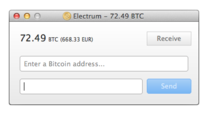

Wallets

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold[46] or store bitcoins, due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the blockchain transaction ledger. A wallet is more correctly defined as something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings" and allows one to access (and spend) them. [8]: ch. 1, glossary Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated.[47] At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.[citation needed]

Software wallets

The first wallet program, simply named Bitcoin, and sometimes referred to as the Satoshi client, was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source software.[7] In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt.[48] After the release of version 0.9, the software bundle was renamed Bitcoin Core to distinguish itself from the underlying network.[49][50] Bitcoin Core is, perhaps, the best known implementation or client. Forks of Bitcoin Core exist, such as Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Unlimited,[51] and Parity Bitcoin.[52]

There are several modes in which wallets can operate. They have an inverse relationship with regard to trustlessness and computational requirements.[citation needed]

- Full clients verify transactions directly by downloading a full copy of the blockchain (over 150 GB as of January 2018[update]).[citation needed] They do not require trust in any external parties. Full clients check the validity of mined blocks, preventing them from transacting on a chain that breaks or alters network rules.[8]: ch. 1 Because of its size and complexity, downloading and verifying the entire blockchain is not suitable for all computing devices.[citation needed]

- Lightweight clients consult full nodes to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire blockchain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to set up and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet, however, the user must trust full nodes, as it can report faulty values back to the user. Lightweight clients follow the longest blockchain and do not ensure it is valid, requiring trust in full nodes.[53]

Third-party internet services called online wallets or webwallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware.[54] As a result, the user must have complete trust in the online wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such a security breach occurred with Mt. Gox in 2011.[55]

Cold storage

Wallet software is targeted by hackers because of the lucrative potential for stealing bitcoins.[30] A technique called "cold storage" keeps private keys out of reach of hackers; this is accomplished by keeping private keys offline at all times[56][8]: ch. 4 by generating them on a device that is not connected to the internet.[57]: 39 The credentials necessary to spend bitcoins can be stored offline in a number of different ways, from specialized hardware wallets to simple paper printouts of the private key.[8]: ch. 10

Paper wallets

A paper wallet is created with a keypair generated on a computer with no internet connection; the private key is written or printed onto the paper and then erased from the computer.[8]: ch. 4 The paper wallet can then be stored in a safe physical location for later retrieval.[57]: 39

Physical wallets can also take the form of metal token coins[58] with a private key accessible under a security hologram in a recess struck on the reverse side.[59]: 38 The security hologram self-destructs when removed from the token, showing that the private key has been accessed.[60] Originally, these tokens were struck in brass and other base metals, but later used precious metals as bitcoin grew in value and popularity.[59]: 80 Coins with stored face value as high as ₿1,000 have been struck in gold.[59]: 102–104 The British Museum's coin collection includes four specimens from the earliest series[59]: 83 of funded bitcoin tokens; one is currently on display in the museum's money gallery.[61] In 2013, a Utah manufacturer of these tokens was ordered by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to register as a money services business before producing any more funded bitcoin tokens.[58][59]: 80

Hardware wallets

A hardware wallet is a computer peripheral that signs transactions as requested by the user. These devices store private keys and carry out signing and encryption internally,[56] and do not share any sensitive information with the host computer except already signed (and thus unalterable) transactions.[62] Because hardware wallets never expose their private keys, even computers that may be compromised by malware do not have a vector to access or steal them.[57]: 42–45

The user sets a passcode when setting up a hardware wallet.[56] As hardware wallets are tamper-resistant,[62][8]: ch. 10 the passcode will be needed to extract any money.[62]

History

Background

Before bitcoin, several digital cash technologies were released, starting with the issuer-based ecash protocols of David Chaum.[63] The idea that solutions to computational puzzles could have some value was first proposed by cryptographers Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor in 1992.[63] The concept was independently rediscovered by Adam Back who developed hashcash, a proof-of-work scheme for spam control in 1997.[64] The first proposals for distributed digital scarcity-based cryptocurrencies came from cypherpunks Wei Dai (b-money) and Nick Szabo (bit gold).[65] In 2004, Hal Finney developed reusable proof of work using hashcash as its proof-of-work algorithm.[66] These various attempts were not successful:[63] Chaum's concept required centralized control and no banks wanted to sign on, hashcash had no protection against double-spending, while b-money and bit gold were not resistant to Sybil attacks.[63]

Creation

| External image | |

|---|---|

The domain name bitcoin.org was registered on 18 August 2008.[67] On 31 October 2008, a link to a white paper authored by Satoshi Nakamoto titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System was posted to a cryptography mailing list.[68] Nakamoto implemented the bitcoin software as open-source code and released it in January 2009.[7] Nakamoto's identity remains unknown.[6] All individual components of bitcoin originated in earlier academic literature.[63] Nakamoto's innovation was their complex interplay resulting in the first decentralized, Sybil resistant, Byzantine fault tolerant digital cash system.[63] Nakamoto's paper was not peer-reviewed and initially ignored by academics, who argued that it could not work, based on theoretical models, even though it was working in practice.[63]

On 3 January 2009, the bitcoin network was created when Nakamoto mined the starting block of the chain, known as the genesis block.[69] Embedded in the coinbase of this block was the text "The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks", which is the date and headline of an issue of The Times newspaper.[7]

On 12 January 2009, Hal Finney received the first bitcoin transaction: ten bitcoins from Nakamoto.[70] Wei Dai and Nick Szabo were also early supporters.[69] In 2010, the first known commercial transaction using bitcoin occurred when programmer Laszlo Hanyecz bought two Papa John's pizzas for ₿10,000.[71]

2010–2012

Blockchain analysts estimate that Nakamoto had mined about one million bitcoins[72] before disappearing in 2010 when he handed the network alert key and control of the code repository over to Gavin Andresen. Andresen later became lead developer at the Bitcoin Foundation,[73][74] an organization founded in September 2012 to promote bitcoin.[75]

After early "proof-of-concept" transactions, the first major users of bitcoin were black markets, such as the dark web Silk Road. During its 30 months of existence, beginning in February 2011, Silk Road exclusively accepted bitcoins as payment, transacting ₿9.9 million, worth about $214 million.[22]: 222

2013–2016

In March 2013, the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) established regulatory guidelines for "decentralized virtual currencies" such as bitcoin, classifying American bitcoin miners who sell their generated bitcoins as money services businesses, subject to registration and other legal obligations.[76] In May 2013, US authorities seized the exchange Mt. Gox after discovering it had not registered.[77]

In June 2013, the US Drug Enforcement Administration seized ₿11.02 from a man attempting to use them to by illegal substances. This marked the first time a government agency had seized bitcoins.[78] The FBI seized about ₿30,000[79] in October 2013 from Silk Road, following the arrest of its founder Ross Ulbricht.[80] These bitcoins were sold at blind auction by the United States Marshals Service to venture capitalist Tim Draper.[79]

In December 2013, the People's Bank of China prohibited Chinese financial institutions from using bitcoin.[81] After the announcement, the value of bitcoin dropped,[82] and Baidu no longer accepted bitcoins for certain services.[83] Buying real-world goods with any virtual currency had been illegal in China since at least 2009.[84]

2017–2019

Research produced by the University of Cambridge estimated that in 2017, there were 2.9 to 5.8 million unique users using a cryptocurrency wallet, most of them using bitcoin.[85] In August 2017, the SegWit software upgrade was activated. Segwit was intended to support the Lightning Network as well as improve scalability. The bitcoin price rose almost 50% in the week following SegWit's approval.[86] SegWit opponents, who supported larger blocks as a scalability solution, forked to create Bitcoin Cash, one of many forks of bitcoin.[87]

In February 2018, China imposed a complete ban on Bitcoin trading. Bitcoin price then crashed.[88] The percentage of bitcoin trading in the Chinese renminbi fell from over 90% in September 2017 to less than 1% in June 2018.[89]

Bitcoin prices were negatively affected by several hacks or thefts from cryptocurrency exchanges,[90] even though other cryptocurrencies were stolen as investors worried about the security of cryptocurrency exchanges.[91][92][93] In September 2019, the Intercontinental Exchange began trading of bitcoin futures on its exchange Bakkt.[94]

2020–present

On 13 March 2020, bitcoin fell below $4,000 during a broad market selloff, after trading above $10,000 in February 2020.[95] On 11 March 2020, 281,000 bitcoins were sold, held by owners for only thirty days.[96] This compared to ₿4,131 that had laid dormant for a year or more, indicating that the vast majority of the bitcoin volatility on that day was from recent buyers. During the week of 11 March 2020, cryptocurrency exchange Kraken experienced an 83% increase in the number of account signups over the week of bitcoin's price collapse, a result of buyers looking to capitalize on the low price.[96] These events were attributed to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.[citation needed]

In August 2020, MicroStrategy invested $250 million in bitcoin as a treasury reserve asset.[97] In October 2020, Square, Inc. placed approximately 1% of total assets ($50 million) in bitcoin.[98] In November 2020, PayPal announced that US users could buy, hold, or sell bitcoin.[99] Alexander Vinnik, founder of BTC-e, was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for money laundering in France while refusing to testify during his trial.[100] In December 2020, Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company announced a bitcoin purchase of US$100 million, or roughly 0.04% of its general investment account.[101]

In November 2021, the Taproot network software upgrade was activated, adding support for Schnorr signatures, improved functionality of smart contracts and Lightning Network.[102][103] Before, Bitcoin only used a custom elliptic curve with the ECDSA algorithm to produce signatures.[104][105]: 101

In September 2021, Bitcoin in El Salvador became legal tender, alongside the US dollar.[106]

In October 2021, the SEC approved the ProShares Bitcoin Strategy ETF, a cash-settled futures exchange-traded fund (ETF). The first bitcoin ETF in the United States gained 5% on its first trading day on 19 October 2021.[107][108]

In May 2022, the bitcoin price fell following the collapse of Terra, a stablecoin experiment.[109] By June 13, 2022, the Celsius Network (a decentralized finance loan company) halted withdrawals and resulted in the bitcoin price falling below $20,000.[110][111]

Ordinals, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) on Bitcoin, went live in 2023.[112]

Economics and usage

Use as a currency

Bitcoin is a digital asset designed to work in peer-to-peer transactions as a currency.[113] Bitcoins have three qualities useful in a currency, according to The Economist in January 2015: they are "hard to earn, limited in supply and easy to verify".[114] Per some researchers, as of 2015[update], bitcoin functions more as a payment system than as a currency.[22]

Economists define money as serving the following three purposes: a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account.[115] According to The Economist in 2014, bitcoin functions best as a medium of exchange.[115] However, this is debated, and a 2018 assessment by The Economist stated that cryptocurrencies met none of these three criteria.[116] In 2014 Yale economist Robert J. Shiller wrote that bitcoin has potential as a unit of account for measuring the relative value of goods, as with Chile's Unidad de Fomento, but that "Bitcoin in its present form ... doesn't really solve any sensible economic problem".[117] François R. Velde, Senior Economist at the Chicago Fed, described bitcoin as "an elegant solution to the problem of creating a digital currency".[118] David Andolfatto, Vice President at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated that bitcoin is a threat to the establishment, which he argues is a good thing for the Federal Reserve System and other central banks, because it prompts these institutions to operate sound policies.[119]: 33 [120]

As of 2018[update], the overwhelming majority of bitcoin transactions took place on cryptocurrency exchanges, rather than being used in transactions with merchants.[121] Prices are not usually quoted in units of bitcoin and many trades involve one, or sometimes two, conversions into conventional currencies.[22] Commonly cited reasons for not using Bitcoin include high costs, the inability to process chargebacks, high price volatility, long transaction times, transaction fees (especially for small purchases).[121][122] Still, Bloomberg reported that bitcoin was being used for large-item purchases on the site Overstock.com, and for cross-border payments to freelancers.[123] As of 2015[update], there was little sign of bitcoin use in international remittances despite high fees charged by banks and Western Union who compete in this market.[22] The South China Morning Post, however, mentions the use of bitcoin by Hong Kong workers to transfer money home.[124]

In September 2021, the Bitcoin Law made bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador, alongside the US dollar.[125] The adoption has been criticized both internationally and within El Salvador.[126][127] In particular, in 2022, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) urged El Salvador to reverse its decision.[128] As of 2022[update], the use of Bitcoin in El Salvador remains low: 80% of businesses refused to accept it despite being legally required to.[129] In April 2022, the Central African Republic (CAR) adopted Bitcoin as legal tender alongside the CFA franc,[130] but repealed the reform one year later.[131]

Use as an investment

Bitcoins can be bought on digital currency exchanges. Other methods of investment are bitcoin funds. The first regulated bitcoin fund was established in Jersey in July 2014 and approved by the Jersey Financial Services Commission.[132] On 10 December 2017, the Chicago Board Options Exchange started trading bitcoin futures,[133] followed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which started trading bitcoin futures on 17 December 2017.[134]

Individuals such as Winklevoss twins have purchased large amounts of bitcoin. In 2013, The Washington Post reported a claim that they owned 1% of all the bitcoins in existence at the time.[135] Similarly, Elon Musk's companies SpaceX and Tesla,[136][137] and Michael Saylor's company MicroStrategy[138] have invested massively in bitcoin. Forbes named bitcoin the best investment of 2013.[139] In 2014, Bloomberg named bitcoin one of its worst investments of the year.[140] In 2015, bitcoin topped Bloomberg's currency tables.[141]

The price of bitcoins has gone through cycles of appreciation and depreciation referred to by some as bubbles and busts.[142] According to Mark T. Williams, as of 2014[update], bitcoin had volatility seven times greater than gold, eight times greater than the S&P 500, and 18 times greater than the US dollar.[143] hodl is a term created in December 2013 for holding Bitcoin rather than selling it during periods of volatility. It has been described as a mantra of the Bitcoin community.[144][145][146]

Use by governments

In 2020, Iran announced pending regulations that would require bitcoin miners in Iran to sell bitcoin to the Central Bank of Iran, and the central bank would use it for imports.[147] Iran, as of October 2020, had issued over 1,000 bitcoin mining licenses.[147] The Iranian government initially took a stance against cryptocurrency, but later changed it after seeing that digital currency could be used to circumvent sanctions.[148]

Some constituent states accept tax payments in bitcoin, including Colorado (US)[149] and Zug (Switzerland).[150][151]

Ideology

| External videos | |

|---|---|

According to the European Central Bank, the decentralization of money offered by bitcoin has its theoretical roots in the Austrian school of economics, especially with Friedrich von Hayek's book The Denationalization of Money, in which he advocates a complete free market in the production, distribution and management of money to end the monopoly of central banks.[153]: 22 Sociologist Nigel Dodd, citing the crypto-anarchist Declaration of Bitcoin's Independence, argues that the essence of the bitcoin ideology is to remove money from social, as well as governmental, control.[154][154][152] The Economist describes bitcoin as "a techno-anarchist project to create an online version of cash, a way for people to transact without the possibility of interference from malicious governments or banks".[116][155]

Libertarians and anarchists were attracted to these philosophical ideas.[155] David Golumbia says that the ideas influencing bitcoin advocates emerge from right-wing extremist movements such as the Liberty Lobby and the John Birch Society and their anti-central bank rhetoric, or, more recently, Ron Paul and Tea Party-style libertarianism.[156] Steve Bannon, who owns bitcoins, considers it to be "disruptive populism. It takes control back from central authorities. It's revolutionary."[157] Economist Paul Krugman argues that cryptocurrencies like bitcoin are "something of a cult" based in "paranoid fantasies" of government power.[158]

Economic, legal and environmental concerns

Legal status

The legal status of bitcoin varies substantially from one jurisdiction to another, and is still undefined or changing in many of them.[159] Because of its decentralized nature and its global presence, regulating bitcoin is difficult. However, the use of bitcoin can be criminalized, and shutting down exchanges and the peer-to-peer economy in a given country would constitute a de facto ban.[160] As of 2021[update], nine countries applied an "absolute ban" on trading or using cryptocurrencies (Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Vietnam, and the United Arab Emirates) while another 42 countries had an "implicit ban".[161] Bitcoin is only legal tender in El Salvador.[5]

Alleged bubble and Ponzi scheme

Bitcoin, along with other cryptocurrencies, has been described as an economic bubble by several economists, including at least eight Nobel Prize in Economics laureates, such as Robert Shiller,[117] Joseph Stiglitz,[162] Richard Thaler,[163][9] and Paul Krugman.[158] On the other hand, another recipient of the prize, Robert Shiller, argues that bitcoin is not a bubble. He describes Bitcoin's price growth as an "epidemic", driven by contagious ideas and narratives, where its media-fueled price volatility perpetuates its value and popularity.[164][165]

Journalists, economists, investors, and the central bank of Estonia have voiced concerns that bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme.[166][167][168][169] However, according to law professor Eric Posner "a real Ponzi scheme takes fraud; bitcoin, by contrast, seems more like a collective delusion."[170] A 2014 World Bank report concluded that bitcoin was not a deliberate Ponzi scheme.[171]: 7 Also in 2014, the Swiss Federal Council concluded that bitcoin was not a pyramid scheme as "the typical promises of profits are lacking".[172]: 21 Bitcoin wealth is highly concentrated, with 0.01% holding 27% of in-circulation currency, as of 2021.[173]

Price manipulation investigations

In May 2018, the United States Department of Justice investigated bitcoin traders for possible price manipulation,[174] focusing on practices like spoofing and wash trades.[175] The investigation, which involved key exchanges like Bitstamp, Coinbase, and Kraken, led to subpoenas from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission after these exchanges failed to fully comply with information requests.[176]

In 2018, research published in the Journal of Monetary Economics concluded that price manipulation occurred during the Mt. Gox bitcoin theft and that the market remained vulnerable to manipulation.[177] Research published in The Journal of Finance also suggested that trading associated with increases in the amount of the Tether cryptocurrency and associated trading at the Bitfinex exchange accounted for about half of the price increase in bitcoin in late 2017.[178][179] Bitfinex and Tether denied the claims of price manipulation.[180]

Use in illegal transactions

The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, and law enforcement.[181] Several news outlets have asserted that the popularity of bitcoins hinges on the ability to use them to purchase illegal goods.[113][182] Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says that bitcoin's anonymity encourages money laundering and other crimes.[183][184]

Environmental effects

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c BTC is a commonly used code, but it does not conform to ISO 4217 as BT is the country code of Bhutan, and ISO 4217 requires the first letter used in global commodities to be 'X'.

- ^ a b c XBT, a code that conforms to ISO 4217 though is not officially part of it, is used by Bloomberg L.P.,[14] CNNMoney,[15] and xe.com.[16]

- ^ a b The exact number is ₿20,999,999.9769.[8]: ch. 8

References

- ^ a b "Unicode 10.0.0". Unicode Consortium. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ a b Mick, Jason (12 June 2011). "Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency". Daily Tech. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Bitcoin Core Releases". Retrieved 24 October 2023 – via GitHub.

- ^ a b "Statement of Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director Financial Crimes Enforcement Network United States Department of the Treasury Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Subcommittee on National Security and International Trade and Finance Subcommittee on Economic Policy" (PDF). fincen.gov. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. 19 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ a b "El Salvador's dangerous gamble on bitcoin". The editorial board. Financial Times. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

On Tuesday, the small Central American nation became the first in the world to adopt bitcoin as an official currency.

- ^ a b S., L. (2 November 2015). "Who is Satoshi Nakamoto?". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). "The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and its mysterious inventor". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Antonopoulos, Andreas M. (2014). Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Crypto-Currencies. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-7404-4.

- ^ a b Wolff-Mann, Ethan (27 April 2018). "'Only good for drug dealers': More Nobel prize winners snub bitcoin". Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World: November 2021 Update" (PDF). United States Library of Congress.

- ^ Jones, Benjamin A.; Goodkind, Andrew L.; Berrens, Robert P. (29 September 2022). "Economic estimation of Bitcoin mining's climate damages demonstrates closer resemblance to digital crude than digital gold". Scientific Reports. 12 (12): 14512. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1214512J. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18686-8. PMC 9522801. PMID 36175441.

- ^ Huang, Jon; O’Neill, Claire; Tabuchi, Hiroko (3 September 2021). "Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ de Vries, Alex; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich; Klaaßen, Lena; Stoll, Christian (16 March 2022). "Revisiting Bitcoin's carbon footprint". Joule. 6 (3): 498–502. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2022.02.005. ISSN 2542-4351.

- ^ Romain Dillet (9 August 2013). "Bitcoin Ticker Available On Bloomberg Terminal For Employees". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin Composite Quote (XBT)". CNN Money. CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "XBT – Bitcoin". xe.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. January 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Katie Pisa & Natasha Maguder (9 July 2014). "Bitcoin your way to a double espresso". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (2 April 2013). "The Bitcoin Boom". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Standards vary, but there seems to be a consensus forming around Bitcoin, capitalized, for the system, the software, and the network it runs on, and bitcoin, lowercase, for the currency itself.

- ^ "bitcoin". OxfordDictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "The great chain of being sure about things". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rainer Böhme; Nicolas Christin; Benjamin Edelman; Tyler Moore (2015). "Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 29 (2): 213–238. doi:10.1257/jep.29.2.213.

- ^ "Blockchain Networks: Token Design and Management Overview" (PDF). National Institute of Standards Technology (NIST). p. 32. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (9 June 2014). "The coming digital anarchy". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Joshua A. Kroll; Ian C. Davey; Edward W. Felten (11–12 June 2013). "The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries" (PDF). The Twelfth Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS 2013). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

A transaction fee is like a tip or gratuity left for the miner.

- ^ Mike Orcutt (19 May 2015). "Leaderless Bitcoin Struggles to Make Its Most Crucial Decision". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Orcutt, Mike (19 May 2015). "Leaderless Bitcoin Struggles to Make Its Most Crucial Decision". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "Man Throws Away 7,500 Bitcoins, Now Worth $7.5 Million". CBS DC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Krause, Elliott (5 July 2018). "A Fifth of All Bitcoin Is Missing. These Crypto Hunters Can Help". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ a b Jeffries, Adrianne (19 December 2013). "How to steal Bitcoin in three easy steps". The Verge. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Harney, Alexandra; Stecklow, Steve (16 November 2017). "Twice burned – How Mt. Gox's bitcoin customers could lose again". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ "Cryptocurrency mining operation launched by Iron Bridge Resources". World Oil. 26 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018.

- ^ Woods, Nick (2021). Bitcoin for Beginners: An Introduction to Bitcoin, Blockchain and Cryptocurrency. Publishing Forte. Chapter 4, Section 2. ISBN 9781954937000.

- ^ "Bitcoin boom benefiting TSMC: report". Taipei Times. 4 January 2014.

- ^ a b Ashlee, Vance (14 November 2013). "2014 Outlook: Bitcoin Mining Chips, a High-Tech Arms Race". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Ritchie S. King; Sam Williams; David Yanofsky (17 December 2013). "By reading this article, you're mining bitcoins". qz.com. Atlantic Media Co. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Hampton, Nikolai (5 September 2016). "Understanding the blockchain hype: Why much of it is nothing more than snake oil and spin". Computerworld. IDG. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Tschorsch, Florian; Scheuermann, Björn (2016). "Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey on Decentralized Digital Currencies". IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 18 (3): 2084–2123. doi:10.1109/comst.2016.2535718. S2CID 5115101.

- ^ a b c Gervais, Arthur; Karame, Ghassan O.; Capkun, Vedran; Capkun, Srdjan. "Is Bitcoin a Decentralized Currency?". InfoQ. InfoQ & IEEE Computer Society. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Wilhelm, Alex. "Popular Bitcoin Mining Pool Promises To Restrict Its Compute Power To Prevent Feared '51%' Fiasco". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Simonite, Tom (5 September 2013). "Mapping the Bitcoin Economy Could Reveal Users' Identities". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (21 August 2013). "Five surprising facts about Bitcoin". The Washington Post.

- ^ McMillan, Robert (6 June 2013). "How Bitcoin lets you spy on careless companies". Wired UK. Conde Nast. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Learning Center > Glossary > T > Taint". River Financial, Inc. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ Möser, Malte; Böhme, Rainer; Breuker, Dominic (2013). An Inquiry into Money Laundering Tools in the Bitcoin Ecosystem (PDF). 2013 APWG eCrime Researchers Summit. IEEE. ISBN 978-1-4799-1158-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Adam Serwer & Dana Liebelson (10 April 2013). "Bitcoin, Explained". motherjones.com. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin: Bitcoin under pressure". The Economist. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Skudnov, Rostislav (2012). Bitcoin Clients (PDF) (Bachelor's Thesis). Turku University of Applied Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin Core version 0.9.0 released". bitcoin.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Metz, Cade (19 August 2015). "The Bitcoin Schism Shows the Genius of Open Source". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (17 January 2016). "Is Bitcoin Breaking Up?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Allison, Ian (28 April 2017). "Ethereum co-founder Dr Gavin Wood and company release Parity Bitcoin". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Gervais, Arthur; O. Karame, Ghassan; Gruber, Damian; Capkun, Srdjan. "On the Privacy Provisions of Bloom Filters in Lightweight Bitcoin Clients" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Bill Barhydt (4 June 2014). "3 reasons Wall Street can't stay away from bitcoin". NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "MtGox gives bankruptcy details". bbc.com. BBC. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Daniel (15 December 2017). "How to send bitcoin to a hardware wallet". Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Barski, Conrad; Wilmer, Chris (2015). Bitcoin for the Befuddled. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-573-0.

- ^ a b Staff, Verge (13 December 2013). "Casascius, maker of shiny physical bitcoins, shut down by Treasury Department". The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Ahonen, Elias; Rippon, Matthew J.; Kesselman, Howard (2016). Encyclopedia of Physical Bitcoins and Crypto-Currencies. Elias Ahonen. ISBN 978-0-9950-8990-7.

- ^ Mack, Eric (25 October 2011). "Are physical Bitcoins legal?". CNET. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ British Museum (2012). "Bitcoin token with digital code for bitcoin currency". Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Arapinis, Myrto; Gkaniatsou, Adriana; Karakostas, Dimitris; Kiayias, Aggelos (2019). A Formal Treatment of Hardware Wallets (PDF) (Technical report). University of Edinburgh, IOHK.

- ^ a b c d e f g Narayanan, Arvind; Clark, Jeremy (27 November 2017). "Bitcoin's academic pedigree". Communications of the ACM. 60 (12): 36–45. doi:10.1145/3132259. ISSN 0001-0782.

- ^ Narayanan, Arvind; Bonneau, Joseph; Felten, Edward; Miller, Andrew; Goldfeder, Steven (2016). Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17169-2.

- ^ Tsorsch, Florian; Scheuermann, Bjorn (15 May 2015). "Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey of Decentralized Digital Currencies" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Judmayer, Aljosha; Stifter, Nicholas; Krombholz, Katharina; Weippl, Edgar (2017). "History of Cryptographic Currencies". Blocks and Chains. Springer. pp. 15–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-02352-1_3. ISBN 978-3-031-01224-2.

- ^ Bernard, Zoë (2 December 2017). "Everything you need to know about Bitcoin, its mysterious origins, and the many alleged identities of its creator". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Finley, Klint (31 October 2018). "After 10 Years, Bitcoin Has Changed Everything—And Nothing". Wired. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ a b Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin". Wired. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (30 August 2014). "Hal Finney, Cryptographer and Bitcoin Pioneer, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Cooper, Anderson (16 May 2019). "Meet the man who spent millions worth of bitcoin on pizza". www.cbsnews.com/. CBS News. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ McMillan, Robert. "Who Owns the World's Biggest Bitcoin Wallet? The FBI". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Simonite, Tom. "Meet Gavin Andresen, the most powerful person in the world of Bitcoin". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Odell, Matt (21 September 2015). "A Solution To Bitcoin's Governance Problem". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (1 April 2013). "The Bitcoin Boom". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (20 March 2013). "US regulator Bitcoin Exchanges Must Comply With Money Laundering Laws". Arstechnica. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

Bitcoin miners must also register if they trade in their earnings for dollars.

- ^ Dillet, Romain. "Feds Seize Assets From Mt. Gox's Dwolla Account, Accuse It Of Violating Money Transfer Regulations". Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Sampson, Tim (2013). "U.S. government makes its first-ever Bitcoin seizure". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ a b Ember, Sydney (2 July 2014). "Winner of Bitcoin Auction, Tim Draper, Plans to Expand Currency's Use". DealBook. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Hill, Kashmir. "The FBI's Plan For The Millions Worth Of Bitcoins Seized From Silk Road". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ Kelion, Leo (18 December 2013). "Bitcoin sinks after China restricts yuan exchanges". bbc.com. BBC. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "China bans banks from bitcoin transactions". The Sydney Morning Herald. Reuters. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Baidu Stops Accepting Bitcoins After China Ban". Bloomberg. New York. 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "China bars use of virtual money for trading in real goods". English.mofcom.gov.cn. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Hileman, Garrick; Rauchs, Michel. "Global Cryptocurrency Benchmarking Study" (PDF). Cambridge University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (21 July 2017). "Bitcoin Rallies Sharply After Vote Resolves Bitter Scaling Debate". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Selena Larson (1 August 2017). "Bitcoin split in two, here's what that means". CNN Tech. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ French, Sally (9 February 2017). "Here's proof that this bitcoin crash is far from the worst the cryptocurrency has seen". Market Watch. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ "RMB Bitcoin trading falls below 1 pct of world total". Xinhuanet. Xinhua. 7 July 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude (3 July 2018). "Cryptocurrency exchange theft surges in first half of 2018: report". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Cryptocurrencies Tumble After $32 Million South Korea Exchange Hack". Fortune. 20 July 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Shane, Daniel (11 June 2018). "Billions in cryptocurrency wealth wiped out after hack". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Russell, Jon (10 July 2018). "The crypto world's latest hack sees Israel's Bancor lose $23.5M". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (22 September 2019). "NYSE Owner Launches Long-Awaited Bitcoin Futures". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Bitcoin loses half of its value in two-day plunge". CNBC. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ a b del Castillo, Michael (19 March 2020). "Bitcoin's Magic Is Fading, And That's A Good Thing". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "MicroStrategy buys $250M in Bitcoin as CEO says it's superior to cash". Washington Business Journal. 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Oliver Effron. "Square just bought $50 million in bitcoin". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "PayPal says all users in US can now buy, hold and sell cryptocurrencies". Techcrunch. 13 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Catalin Cimpanu (7 December 2020). "BTC-e founder sentenced to five years in prison for laundering ransomware funds". ZDNet. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Olga Kharif (11 December 2020). "169-Year-Old MassMutual Invests $100 Million in Bitcoin". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (9 June 2021). "Bitcoin just got its first makeover in four years". CNBC. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (14 November 2021). "Bitcoin's biggest upgrade in four years just happened – here's what changes". CNBC. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Houria, Azine; Mohamed Abdelkader, Bencherif; Abderezzak, Guessoum (1 March 2019). "A comparison between the secp256r1 and the koblitz secp256k1 bitcoin curves". Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. 13 (3): 910. doi:10.11591/ijeecs.v13.i3.pp910-918. S2CID 196058538.

- ^ Van Hijfte, Stijn (2020). Blockchain Platforms: A Look at the Underbelly of Distributed Platforms. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1681738925.

- ^ Renteria, Nelson; Wilson, Tom; Strohecker, Karin (9 June 2021). "In a world first, El Salvador makes bitcoin legal tender". Reuters. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ La Monica, Paul (19 October 2021). "The first bitcoin ETF finally begins trading". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Mccrank, John (22 October 2021). "Bitcoin falls from peak, U.S. ETF support questioned". Reuters. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Browne, Ryan (10 May 2022). "Bitcoin investors are panicking as a controversial crypto experiment unravels". CNBC.

- ^ Milmo, Dan (18 June 2022). "Bitcoin value slumps below $20,000 in cryptocurrencies turmoil". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Yaffe-Bellany, David (13 June 2022). "Celsius Network Leads Crypto Markets Into Another Free Fall". The New York Times.

- ^ Behrendt, Philipp (2023). "Taxation of the New Age: New Guidance for the World of Digital Assets". Journal of Tax Practice & Procedure. 25: 47.

- ^ a b "Monetarists Anonymous". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "The magic of mining". The Economist. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Free Exchange. Money from nothing. Chronic deflation may keep Bitcoin from displacing its rivals". The Economist. 15 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are useless". The Economist. 30 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

Lack of adoption and loads of volatility mean that cryptocurrencies satisfy none of those criteria.

- ^ a b Shiller, Robert (1 March 2014). "In Search of a Stable Electronic Currency". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014.

- ^ Velde, François (December 2013). "Bitcoin: A primer" (PDF). Chicago Fed letter. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Andolfatto, David (31 March 2014). "Bitcoin and Beyond: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Virtual Currencies" (PDF). Dialogue with the Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Wile, Rob (6 April 2014). "St. Louis Fed Economist: Bitcoin Could Be A Good Threat To Central Banks". businessinsider.com. Business Insider. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b Murphy, Hannah (8 June 2018). "Who really owns bitcoin now?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Katz, Lily (12 July 2017). "Bitcoin Acceptance Among Retailers Is Low and Getting Lower". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Kharif, Olga (1 August 2018). "Bitcoin's Use in Commerce Keeps Falling Even as Volatility Eases". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Chan, Bernice (16 January 2015). "Bitcoin transactions cut the cost of international money transfers". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Ostroff, Caitlin (9 June 2021). "El Salvador Becomes First Country to Approve Bitcoin as Legal Tender". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Silver, Katie (8 September 2021). "Bitcoin crashes on first day as El Salvador's legal tender". BBC.

- ^ "Majority of Salvadorans do not want bitcoin, poll shows". Reuters. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "IMF urges El Salvador to remove Bitcoin as legal tender". BBC News. 26 January 2022.

- ^ Alvarez, Fernando; Argente, David; Van Patten, Diana (2022). Are Cryptocurrencies Currencies? Bitcoin as Legal Tender in El Salvador (Report). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w29968.

- ^ "Bitcoin Declared Legal Currency in Central African Republic". Bloomberg.com. 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions on Central African Republic". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Jersey approve Bitcoin fund launch on island". BBC News. 10 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin futures surge in first day of trading". CBS News. 11 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Chicago Mercantile Exchange jumps into bitcoin futures". CBS News. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. "The $11 million in bitcoins the Winklevoss brothers bought is now worth $32 million". The Switch. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Maidenberg, Micah; Driebusch, Corrie; Jin, Berber (17 August 2023). "A Rare Look Into the Finances of Elon Musk's Secretive SpaceX". WSJ. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Wall, Robert (21 July 2022). "Tesla Sells 75% of Its Bitcoin Purchases". WSJ. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "MicroStrategy Adds to Its Bitcoin Stash in Q2, Crypto Aids Results". Forbes.

- ^ Hill, Kashmir. "How You Should Have Spent $100 In 2013 (Hint: Bitcoin)". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Steverman, Ben (23 December 2014). "The Best and Worst Investments of 2014". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Gilbert, Mark (29 December 2015). "Bitcoin Won 2015. Apple ... Did Not". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Moore, Heidi (3 April 2013). "Confused about Bitcoin? It's 'the Harlem Shake of currency'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Williams, Mark T. (21 October 2014). "Virtual Currencies – Bitcoin Risk" (PDF). World Bank Conference Washington DC. Boston University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Kaminska, Izabella (22 December 2017). "The HODL". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Montag, Ali (26 August 2018). "'HODL,' 'whale' and 5 other cryptocurrency slang terms explained". CNBC. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Hajric, Vildana (19 November 2020). "All the Bitcoin Lingo You Need to Know as Crypto Heats Up". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Iran: New Crypto Law Requires Selling Bitcoin Directly to Central Bank to Fund Imports". aawsat.com. 31 October 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Iran Is Pivoting to Bitcoin". vice.com. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Colorado accepts cryptocurrency to pay taxes, moving the state "tech forward"". The Denver Post. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Canton Zug to accept cryptocurrencies for tax payment beginning in 2021". Canton of Zug. 3 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Kanton Zug akzeptiert Kryptowährungen bei Steuern" (in German). Schweizerischen Radio- und Fernsehgesellschaft. 3 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ a b Tourianski, Julia (13 August 2014). "The Declaration Of Bitcoin's Independence". Archive.org. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ European Central Bank (2012). Virtual Currency Schemes (PDF). Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank. ISBN 978-92-899-0862-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2012.

- ^ a b Dodd, Nigel (May 2018). "The Social Life of Bitcoin". Theory, Culture & Society. 35 (3): 35–56. doi:10.1177/0263276417746464.

"Pre-print link for convenience" (PDF). LSE Research Online. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018. - ^ a b Feuer, Alan (14 December 2013). "The Bitcoin Ideology". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Golumbia, David (2015). Lovink, Geert (ed.). Bitcoin as Politics: Distributed Right-Wing Extremism. Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam. pp. 117–131. ISBN 978-90-822345-5-8. SSRN 2589890.

- ^ Peters, Jeremy W.; Popper, Nathaniel (14 June 2018). "Stephen Bannon Buys Into Bitcoin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (29 January 2018). "Bubble, Bubble, Fraud and Trouble". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

- ^ Tasca, Paolo (7 September 2015). "Digital Currencies: Principles, Trends, Opportunities, and Risks". SSRN 2657598.

- ^ "China May Be Gearing Up to Ban Bitcoin". Paste. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

The decentralized nature of bitcoin is such that it is impossible to "ban" the cryptocurrency, but if you shut down exchanges and the peer-to-peer economy running on bitcoin, it's a de facto ban.

- ^ "Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World" (PDF). Library of Congress. The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. June 2018. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Costelloe, Kevin (29 November 2017). "Bitcoin 'Ought to Be Outlawed,' Nobel Prize Winner Stiglitz Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

It doesn't serve any socially useful function.

- ^ "Economics Nobel prize winner, Richard Thaler: "The market that looks most like a bubble to me is Bitcoin and its brethren"". ECO Portuguese Economy. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "Don't Call Bitcoin a Bubble. It's an Epidemic - Bloomberg". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021.

- ^ Shiller, Robert J. (April 2017). "Narrative Economics". American Economic Review. 107 (4): 967–1004. doi:10.1257/aer.107.4.967. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Braue, David (11 March 2014). "Bitcoin confidence game is a Ponzi scheme for the 21st century". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Clinch, Matt (10 March 2014). "Roubini launches stinging attack on bitcoin". CNBC. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ "This Billionaire Just Called Bitcoin a 'Pyramid Scheme'". Fortune. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Ott Ummelas & Milda Seputyte (31 January 2014). "Bitcoin 'Ponzi' Concern Sparks Warning From Estonia Bank". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Posner, Eric (11 April 2013). "Fool's Gold: Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme—the Internet's favorite currency will collapse". Slate. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Kaushik Basu (July 2014). "Ponzis: The Science and Mystique of a Class of Financial Frauds" (PDF). World Bank Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Federal Council report on virtual currencies in response to the Schwaab (13.3687) and Weibel (13.4070) postulates" (PDF). Federal Council (Switzerland). Swiss Confederation. 25 June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (20 December 2021). "Bitcoin's 'One Percent' Controls Lion's Share of the Cryptocurrency's Wealth". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ Dean, James (25 May 2018). "Bitcoin investigation to focus on British traders, US officials examine manipulation of cryptocurrency prices". The Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Cornish, Chloe (24 May 2018). "Bitcoin slips again on reports of US DoJ investigation". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Rubin, Gabriel T.; Michaels, Dave; Osipovich, Alexander (8 June 2018). "U.S. regulators demand trading data from bitcoin exchanges in manipulation probe". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 June 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018. (subscription required)

- ^ Gandal, Neil; Hamrick, J.T.; Moore, Tyler; Oberman, Tali (May 2018). "Price manipulation in the Bitcoin ecosystem". Journal of Monetary Economics. 95: 86–96. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.12.004. S2CID 26358036.

- ^ Griffin, John M.; Shams, Amin (August 2020). "Is Bitcoin Really Untethered?". The Journal of Finance. 75 (4): 1913–1964. doi:10.1111/jofi.12903. ISSN 0022-1082.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (13 June 2018). "Bitcoin's Price Was Artificially Inflated Last Year, Researchers Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Shaban, Hamza (14 June 2018). "Bitcoin's astronomical rise last year was buoyed by market manipulation, researchers say". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Lavin, Tim (8 August 2013). "The SEC Shows Why Bitcoin Is Doomed". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Ball, James (22 March 2013). "Silk Road: the online drug marketplace that officials seem powerless to stop". theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Montag, Ali (9 July 2018). "Nobel-winning economist: Authorities will bring down 'hammer' on bitcoin". CNBC. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Newlands, Chris (9 July 2018). "Stiglitz, Roubini and Rogoff lead joint attack on bitcoin". Financial News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Huang, Jon; O'Neill, Claire; Tabuchi, Hiroko (3 September 2021). "Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b de Vries, Alex; Stoll, Christian (December 2021). "Bitcoin's growing e-waste problem". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 175: 105901. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105901. ISSN 0921-3449. S2CID 240585651. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Lal, Apoorv; Zhu, Jesse; You, Fengqi (13 November 2023). "From Mining to Mitigation: How Bitcoin Can Support Renewable Energy Development and Climate Action". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 11 (45): 16330–16340. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c05445. ISSN 2168-0485. S2CID 264574360. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Stoll, Christian; Klaaßen, Lena; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich; Neumüller, Alexander (June 2023). Climate Impacts of Bitcoin Mining in the U.S. (Report). Working Paper Series. MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

Further reading

- Nakamoto, Satoshi (31 October 2008). "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF). bitcoin.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.