Academic art

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

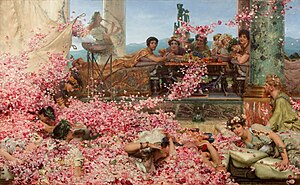

The Birth of Venus by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1879); Phaedra by Alexandre Cabanel (1880); The Roses of Heliogabalus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888) |

Academic art, academicism, or academism, is a style of painting and sculpture produced under the influence of European academies of art. This method extended its influence throughout the Western world over several centuries, from its origins in Italy in the mid-16th century, until its dissipation in the early 20th century. Its reached its apogee in the 19th century, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. In this period, the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts were very influential, combining elements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres a key figure in the formation of the style in painting. The success of the French model led to the founding of countless other art academies in several countries. Later painters who tried to continue the synthesis included William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart among many others. In sculpture, academic art is characterized by a tendency towards monumentality, as in the works of Auguste Bartholdi and Daniel Chester French.

The academies were established to replace medieval artists' guilds and aimed to systematize the teaching of art. They emphasized the emulation of established masters and the classical tradition, downplaying the importance of individual creativity, valuing instead collective, aesthetic and ethical concepts. By helping raise the professional status of artists, the academies distanced them from artisans and brought them closer to intellectuals. They also played a crucial role in organizing the art world, controlling cultural ideology, taste, criticism, the art market, as well as the exhibition and dissemination of art. They wielded significant influence due to their association with state power, often acting as conduits for the dissemination of artistic, political, and social ideals, by deciding what was considered "official art". As a result, they faced criticism and controversy from artists and others on the margins of these academic circles, and their restrictive and universalist regulations are sometimes considered a reflection of absolutism.

Overall, academicism has had a significant impact on the development of art education and artistic styles. Its artists rarely showed interest in depicting the everyday or profane. Thus, academic art is predominantly idealistic rather than realistic, aiming to create highly polished works through the mastery of color and form. Although smaller works such as portraits, landscapes and still-lifes were also produced, the movement and the contemporary public and critics most valued large history paintings showing moments from narratives that were very often taken from ancient or exotic areas of history and mythology, though less often the traditional religious narratives. Orientalist art was a major branch, with many specialist painters, as were scenes from classical antiquity and the Middle Ages. Academic art is also closely related to Beaux-Arts architecture, as well as classical music and dance, which developed simultaneously and hold to a similar classicizing ideal.

Although production of academic art continued into the 20th century, the style had become vacuous, and was strongly rejected by the artists of set of new art movements, of which Realism and Impressionism were some of the first. In this context, the style is often called "eclecticism", "art pompier" (pejoratively), and sometimes linked with "historicism" and "syncretism". By World War I, it had fallen from favor almost completely with critics and buyers, before regaining some appreciation since the end of the 20th century.

Origins and theoretical foundations[edit]

The first art academies in Renaissance Italy[edit]

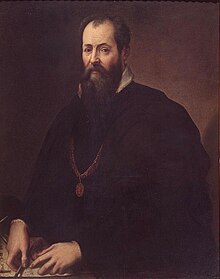

The first academy of art was founded in Florence by Cosimo I de' Medici, on 13 January 1563, under the influence of the architect Giorgio Vasari, who called it the Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing) as it was divided in two different operative branches. While the company was a kind of corporation that every working artist in Tuscany could join, the academy comprised only the most eminent artists of Cosimo's court, and had the task of overseeing all Florentine artistic activities, including teaching, and safeguarding local cultural traditions. Among the founding members were Michelangelo, Bartolomeo Ammannati, Agnolo Bronzino and Francesco da Sangallo. In this institution, students learned the "arti del disegno" (a term coined by Vasari) and heard lectures on anatomy and geometry.[1][2][3] The Accademia's fame spread quickly, to the point that, within just five months of its founding, important Venetian artists such as Titian, Salviati, Tintoretto and Palladio applied for admission, and in 1567, King Philip II of Spain consulted it about plans for El Escorial.[4]

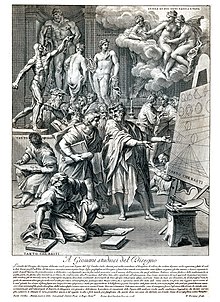

Another academy, the Accademia de i Pittori e Scultori di Roma (Academy of Painters and Sculptors of Rome), better known as the Accademia di San Luca (named after the patron saint of painters, St. Luke), was founded about a decade later in Rome. It served an educational function and was more concerned with art theory than the Florentine one, attaching great importance to attending theoretical lectures, debates and drawing classes.[5] Twelve academics were immediately appointed as teachers, establishing a series of disciplinary measures for studies and instituting a system of awards for the most capable students.[6]

In 1582, the painter and art instructor Annibale Carracci opened his very influential Accademia dei Desiderosi (Academy of the Desirous) in Bologna without official support; in some ways, this was more like a traditional artist's studio, but that he felt the need to label it as an "academy" demonstrates the attraction of the idea at the time.[7]

The emergence of art academies in the 16th century was due to the need to respond to new social demands. Several states, which were moving towards absolutism, realized that it was necessary to create an art that specifically identified them and served as a symbol of civic unity, and was also capable of symbolically consolidating the status of their rulers. In this process, the Catholic Church, then the greatest political force and social unifier in Europe, began to lose some of its influence as a result of the greater secularization of societies. Sacred art, by far the largest field of artistic expression throughout the Middle Ages, came to coexist with an expanding profane art, derived from classical sources, which had been experiencing a slow revival since the 12th century, and which, by the time of the Renaissance, had been established as the most prestigious cultural reference and model of quality.[8][9]

This re-emergence of classicism required artists to become more cultured, in order to competently transpose this reference to the visual arts. At the same time, the old system of artistic production, organized by guilds—class associations of an artisanal nature, linked more to mechanical crafts than to intellectual erudition—began to be seen as outdated and socially unworthy, as artists began to desire equality with the intellectual versed in the liberal arts, since art itself began to be seen not only as a technical task, as it had been for centuries, but mainly as a way of acquiring and transmitting knowledge. In this new context, painting and sculpture began to be seen as theorizable, just as other arts such as literature and especially poetry were already. However, if on the one hand the artists did rise socially, on the other they lost the security of market insertion that the guild system provided, having to live in the uncertain expectation of individual protection by some patron.[10]

Standardization: French academicism and visual arts[edit]

If Italy was to be credited with founding this new type of institution, France was responsible for taking the model to a first stage of great order and stability. The country's first attempts to establish academies like the Italian ones also took place in the 16th century, during the reign of King Henry III, especially through the work of the poet Jean-Antoine de Baïf, who founded an academy linked to the French Crown. Like its Italian counterparts, it was primarily philological-philosophical in nature, but it also worked on concepts relating to the arts and sciences. Although it developed intense activity with regular debates and theoretical production, defending classical principles, it lacked an educational structure and had a brief existence.[11]

The Accademia di San Luca later served as the model for the French Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), founded in 1648 by a group of artists led by Charles Le Brun, and which later became the Académie des Beaux-Arts (Academy of Fine Arts). Its objective was similar to the Italian one, to honor artists "who were gentlemen practicing a liberal art" from craftsmen, who were engaged in manual labor. This emphasis on the intellectual component of artmaking had a considerable impact on the subjects and styles of academic art.[12][13][14]

After an ineffective start, the Académie royale was reorganized in 1661 by King Louis XIV, whose aim was to control all the country's artistic activity,[15] and in 1671, it came under the control of First Minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who confirmed Le Brun as director. Together, they made it the main executive arm of a program to glorify the king's absolutist monarchy, definitively establishing the school's association with the State and thereby vesting it with enormous directive power over the entire national art system, which contributed to making France the new European cultural center, displacing the hitherto Italian supremacy. But while for the Italian Renaissance, art was also a survey of the natural world, for Le Brun it was above all the product of an acquired culture, inherited forms and an established tradition.[16][17]

During this period, academic doctrine reached the peak of its rigor, comprehensiveness, uniformity, formalism and explicitness, and according to art historian Moshe Barasch, at no other time in the history of art theory has the idea of perfection been more intensely cultivated as the artist's highest goal, with the production of the Italian High Renaissance as the ultimate model. Thus, Italy continued to be an invaluable reference, so much so that a branch was established in Rome in 1666, the French Academy, with Charles Errard as its first director.[16]

At the same time, a controversy occurred among the members of the Académie, which would come to dominate artistic attitudes for the rest of the century. This "battle of styles" was a conflict over whether Peter Paul Rubens or Nicolas Poussin was a suitable model to follow. Followers of Poussin, called "poussinistes", argued that line (disegno) should dominate art, because of its appeal to the intellect, while followers of Rubens, called "rubenistes", argued that color (colore) should be the dominant feature, because of its appeal to emotion.[18] The debate was revived in the early 19th century, under the movements of Neoclassicism typified by the art of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, and Romanticism typified by the artwork of Eugène Delacroix. Debates also occurred over whether it was better to learn art by looking at nature, or at the artistic masters of the past.[19]

Transformations and diffusion of the French model[edit]

At the end of Louis XIV's reign, the academic style and teachings strongly associated with his monarchy began to spread throughout Europe, accompanying the growth of the urban nobility. A series of other important academies were formed across the continent, inspired by the success of the French Académie: the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Nuremberg (1662), the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (1696), the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna (1698), the Royal Drawing Academy in Stockholm (1735), the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid (1752), the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg (1757), and the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan (1776), to name a few. In England, this was the Royal Academy of Arts, which was founded in 1768 with a mission "to establish a school or academy of design for the use of students in the arts".[20][21]

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, founded in 1754, may be taken as a successful example in a smaller country, which achieved its aim of producing a national school and reducing the reliance on imported artists. The painters of the Danish Golden Age of roughly 1800–1850 were nearly all trained there, and drawing on Italian and Dutch Golden Age paintings as examples, many returned to teach locally.[22] The history of Danish art is much less marked by tension between academic art and other styles than is the case in other countries.[citation needed]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the model expanded to America, with the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico being founded in 1783, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the United States in 1805,[23] and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Brazil in 1826.[24] Meanwhile, back in Italy, another major center of irradiation appeared, Venice, launching the tradition of urban views and "capriccios", fantasy landscape scenes populated by ancient ruins, which became favorites of noble travelers on the Grand Tour.[23]

Development of the academic style[edit]

Early challenges: the Enlightenment and Romanticism[edit]

Even with its wide spread, the academic system began to be seriously challenged through the actions of intellectuals linked to the Enlightenment. For them, academicism had become an outdated model, excessively rigid and dogmatic; they criticized the methodology, which they believed produced an art that was merely servile to ancient examples, and condemned the institutional administration, which they considered corrupt and despotic.[25] However, an important Enlightenment figure like Diderot subscribed to much of the academic ideal, supported the hierarchy of genres (see below), and said that "the imagination creates nothing".[26] At the end of the 18th century, following the turmoil of the French Revolution, a real campaign was mounted against the teaching of the Academy, which was identified as a symbol of the Ancien Régime. In 1793, the painter Jacques-Louis David, closely linked to the revolutionaries, took over the direction of the artistic affairs of the new republic and, after complying with the request of numerous artists dissatisfied with the institution's bureaucracy and system of privileges, dissolved the Parisian academies and all the other royal academies in the countryside. However, the extinction of the old schools was temporary, as a Committee for the Arts was subsequently organized, which led to the founding in 1795 of a new institution, the Institut de France, which included an artistic section and was responsible for reorganizing the national arts system.[25]

The challenges to academicism in France, however, were more nominal than real. Art courses returned to operating in broadly the same way as before, the hierarchy of genres was resurrected, the awards and salons were maintained, the branch in Rome remained active, and the State continued to be the biggest sponsor of art. Quatremère de Quincy, the secretary of the new Institut, which had been born as an apparatus of revolutionary renewal, paradoxically believed that art schools served to preserve traditions, not to found new ones.[25] The greatest innovations he introduced were the idea of reunifying the arts under an atmosphere of egalitarianism, eliminating honorary titles for members and some other privileges, and his attempt to make administration more transparent, eminently public and functional. In reinterpreting the Platonic theory that the arts are questionable because they are imperfect imitations of an abstract ideal reality, he considered this idea only in a moral sphere, politicized and republicanized it, relating the truth of the arts to that of social institutions. He also claimed that the political reality of the republic was a reflection of the republic of the arts that he sought to establish. But beyond the ideas, in practice, authoritarianism, which was one of the reasons given for the extinction of the royal academies, continued to be practiced in the republican administration.[27]

Another attack on the academic model came from the early Romantics, at the turn of 18th to 19th centuries, who preached a practice centered on individual originality and independence. Around 1816, the painter Théodore Géricault, one of the exponents of French Romanticism, stated:

These schools keep their pupils in a state of constant emulation... I note with sadness that, since the establishment of these schools, there has been a great effect: they have given service to thousands of mediocre talents... Painters enter there too young, and therefore the traces of individuality that survive the Academy are imperceptible. One can see, with real chagrin, about ten or twelve compositions every year that are practically identical in execution, because in their quest for perfection, they lose their originality. One way of drawing, one type of color, one arrangement for all systems...[28]

Stylistic trends and contradictions[edit]

Since the onset of the Poussiniste-Rubeniste debate, many artists worked between the two styles. In the 19th century, in the revived form of the debate, the attention and the aims of the art world became to synthesize the line of Neoclassicism with the color of Romanticism. One artist after another was claimed by critics to have achieved the synthesis, among them Théodore Chassériau, Ary Scheffer, Francesco Hayez, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and Thomas Couture. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a later academic artist, commented that the trick to being a good painter is seeing "color and line as the same thing". Thomas Couture promoted the same idea in a book he authored on art method—arguing that whenever one said a painting had better color or better line it was nonsense, because whenever color appeared brilliant it depended on line to convey it, and vice versa; and that color was really a way to talk about the "value" of form.

Historicism[edit]

Another development during this period, called historicism, included adopting historic styles or imitating the work of historic artists and artisans in order to show the era in history that the painting depicted. In the history of art, after Neoclassicism which in the Romantic era could itself be considered a historicist movement, the 19th century included a new historicist phase characterized by an interpretation not only of Greek and Roman classicism, but also of succeeding stylistic eras, which were increasingly respected. This is best seen in the work of Baron Jan August Hendrik Leys, a later influence on James Tissot. It is also seen in the development of the Neo-Grec style. Historicism is also meant to refer to the belief and practice associated with academic art that one should incorporate and conciliate the innovations of different traditions of art from the past.

Allegory in art[edit]

The art world also grew to give increasing focus on allegory in art. Theories of the importance of both line and color asserted that through these elements an artist exerts control over the medium to create psychological effects, in which themes, emotions, and ideas can be represented. As artists attempted to synthesize these theories in practice, the attention on the artwork as an allegorical or figurative vehicle was emphasized. It was held that the representations in painting and sculpture should evoke Platonic forms, or ideals, where behind ordinary depictions one would glimpse something abstract, some eternal truth. Hence, Keats' famous musing "Beauty is truth, truth beauty". The paintings were desired to be an "idée", a full and complete idea. Bouguereau is known to have said that he would not paint "a war", but would paint "War". Many paintings by academic artists are simple nature allegories with titles like Dawn, Dusk, Seeing, and Tasting, where these ideas are personified by a single nude figure, composed in such a way as to bring out the essence of the idea.

Idealism[edit]

Stylistically, academic art cultivated the ideal of perfection and at the same time selective imitation of reality (mimesis), which had existed since Aristotle. With perfect mastery of color, light and shadow, forms were created in a quasi-photorealistic manner. Some paintings have a "polished finish" where no brushstroke can be recognized on the finished work. After the oil sketch, the artist would produce the final painting with the academic "fini", changing the painting to meet stylistic standards and attempting to idealize the images and add perfect detail. Similarly, perspective was constructed geometrically on a flat surface and was not really the product of sight.

The trend in art was also towards greater idealism, which is contrary to realism, in that the figures depicted were made simpler and more abstract—idealized—in order to be able to represent the ideals they stood in for. This would involve both generalizing forms seen in nature, and subordinating them to the unity and theme of the artwork.

Hierarchy of genres[edit]

The representation of the various emotions was codified in detail by academicism[29] and the artistic genres themselves were subjected to a scale of prestige. Because history and mythology were considered plays or dialectics of ideas, a fertile ground for important allegory, using themes from these subjects was regarded as the most serious form of painting. This hierarchy of genres, originally created in the 17th century, was highly valued, where history painting (also known as the "grande genre")—classical, religious, mythological, literary, and allegorical subjects—was placed at the top, followed by "minor genres"—portraiture, genre painting, landscapes, and still-lifes.[30][31]

The historical genre, the most appreciated, included works that conveyed themes of an inspirational and ennobling nature, essentially with an ethical background, consistent with the tradition founded by masters such as Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. Paul Delaroche is a typifying example of French history painting and Benjamin West of the British-American vogue for painting scenes from recent history. Paintings by Hans Makart are often larger than life historical dramas, and he combined this with a historicism in decoration to dominate the style of 19th-century Vienna culture. Portraits included large-format depictions of people, suitable for their public glorification, but also smaller pieces for private use. Everyday scenes, also known as genre scenes, portrayed common life in a symbolic manner, landscapes offered perspectives of idealized virgin nature or city panoramas, and still-lifes consisted of groupings of diverse objects in formal compositions.[30][31]

The justification for this hierarchization lay in the idea that each genre had an inherent and specific moral force. Thus, an artist could convey a moral principle with much more power and ease through a historical scene than, for example, through a still-life. Furthermore, following Greek concepts, it was believed that the highest form of art was the ideal representation of the human body, hence landscapes and still-lifes, in which man did not appear, had little prestige. Finally, with a primarily social and didactic function, academic art favored large works and large-format portraits, more suitable for viewing by large groups of spectators and better suited to decorating public spaces.[30][31]

All of these trends were influenced by the theories of the German philosopher Hegel, who held that history was a dialectic of competing ideas, which eventually resolved in synthesis.

Maturation: an increasingly bourgeois art form[edit]

Napoleon was the "swan song" of the concept of art as a vehicle of moral values and a mirror of virtue. He actively patronized and employed artists to portray his personal glory, that of his Empire and of his political and military conquests. After him, the fragmentation and weakening of ideals began to become visible and irreversible.[32] With the cooling of the libertarian ardor of the first Romantics, with the final failure of Napoleon's imperialist project, and with the popularization of an eclectic style that blended Romanticism and Neoclassicism, adapting them to the purposes of the bourgeoisie, which became one of the greatest sponsors of the arts, the emergence of a general feeling of resignation appeared, as well as a growing prevalence of individual bourgeois taste against idealistic collective systems. Soon the preferences of this social class, now so influential, penetrated higher education and became worthy objects of representation, changing the hierarchy of genres and proliferating portraits and all the so-called minor genres, such as everyday scenes and still-lifes, which became more pronounced as the century progressed.[33]

The bourgeoisie's support for academies was a way of demonstrating education and acquiring social prestige, bringing them closer to the cultural and political elites. Finally, Neo-Gothic revivalism, the development of a taste for the picturesque as an autonomous aesthetic criterion, the revival of Hellenistic eclecticism, the progress of medievalist, orientalist and folkloric studies, the growing participation of women in art production, the valorisation of handicrafts and applied arts, opened up other fronts of appreciation for the visual arts, finding other truths worthy of appreciation that had previously been neglected and relegated to the margins of official culture.[34][35][36] As a result of this great cultural transformation, the academic educational model, in order to survive, had to incorporate some of these innovations, but it broadly maintained the established tradition, and managed to become even more influential, continuing to inspire not only Europe, but also America and other countries colonized by Europeans, throughout the 19th century.[37]

Another factor in this academic revival, even in the face of a profoundly changing scenario, was the reiteration of the idea of art as an instrument of political affirmation by nationalist movements in several countries.[37]

Apotheosis: Parisian salons and further influence[edit]

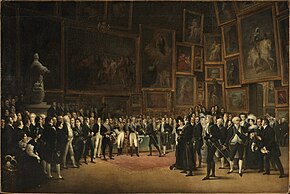

The 19th century was the heyday of the academies, in the sense that their output became extremely well accepted among a much wider—but often less cultured and less demanding—public, giving academic art a popularity as great as that enjoyed today by cinema, and with an equally popular theme, covering everything from traditional historical subjects to comic vignettes, from sweet and sentimental portraits to medievalist or picturesque scenes from exotic Eastern countries, something unthinkable during the Ancien Régime.[38]

By the second half of the 19th century, academic art had saturated European society. Exhibitions were held often, with the most popular exhibition being the Paris Salon, and beginning in 1903, the Salon d'Automne. These salons were large scale events that attracted crowds of visitors, both native and foreign. As much a social affair as an artistic one, 50,000 people might visit on a single Sunday, and as many as 500,000 could see the exhibition during its two-month run. Thousands of paintings were displayed, hung from just below eye level all the way up to the ceiling in a manner now known as "Salon style". A successful showing at the salon was a seal of approval for an artist, making his work saleable to the growing ranks of private collectors. Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme were leading figures of this art world.[39][40]

During the reign of academic art, the paintings of the Rococo era, previously held in low favor, were revived to popularity, and themes often used in Rococo art such as Eros and Psyche were popular again. The academic art world also admired Raphael, for the idealism of his work, in fact preferring him over Michelangelo.

England[edit]

In England, the influence of the Royal Academy grew as its association with the State consolidated. In the first half of the 19th century, the Royal Academy already exercised direct or indirect control over a vast network of galleries, museums, exhibitions and other artistic societies, and over a complex of administrative agencies that included the Crown, parliament and other state departments, which found their cultural expression through their relations with the academic institution.[41][42] The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition gained momentum at the time and has been staged annually without interruption to the present day.

As the century progressed, challenges to this primacy began to emerge, demanding that its relations with the government be clarified, and the institution began to pay more attention to market aspects in a society that was becoming more heterogeneous and cultivating multiple aesthetic tendencies. Subsidiary schools were also opened in various cities to meet regional demands. By the middle of the 19th century, the Royal Academy had already lost control over British artistic production, faced with the multiplication of independent creators and associations, but continued, facing internal tensions, to try to preserve it. Around 1860, it was again stabilized through new strategies of monopolizing power, incorporating new trends into its orbit, such as promoting the previously ignored technique of watercolor, which had become vastly popular, accepting the admission of women, requiring new members in an enlarged membership to renounce their affiliation to other societies and reforming its administrative structure to appear as a private institution, but imbued with a civic purpose and a public character. In this way, it managed to administer a significant part of the British artistic universe throughout the 19th century, and despite the opposition of societies and groups of artists such as the Pre-Raphaelites, it managed to remain a disciplinary, educational and consecrating agency of the greatest importance, able to largely accompany the progress of modernism, contradicting a common view that academies are invariably reactionary.[41][42]

Germany[edit]

In Germany, the academic spirit initially encountered some resistance to its full implementation. Already at the end of the 18th century, theorists such as Baumgarten, Schiller and Kant had promoted the autonomy of Aesthetics through the concept of "art for art's sake", and had emphasized the importance of the artist's self-education, against the massification imposed by civilization and its institutions, seeing the collectivizing structure and impersonal nature of academia as a threat to their desires for creative freedom, individualistic inspiration, and absolute originality. In this vein, art criticism began to take on distinctly sociological colors.[43]

Part of this reaction was due to the activity of the Nazarenes, a group of painters who sought a return to a Renaissance style and medieval practices in a spirit of austerity and fraternity. Under their influence, masterclasses were introduced—paradoxically within the academies themselves—which sought to group promising students around a master, who was responsible for their instruction, but with much more concentrated attention and care than in the more generalist French system, based on the assumption that such more individualized treatment could provide a stronger and deeper education. This method was first instituted at the Dusseldorf Academy and progressed slowly, but over the course of the 19th century, it became common to all German academies, and was also imitated in other northern European countries. Interesting results of the masterclasses were the beginning of a tradition of large-scale mural painting and the steering of the local avant-garde along less iconoclastic lines than the Parisian ones.[44]

United States[edit]

The influence of the Royal Academy extended across the ocean and strongly determined the foundation and direction of American art from the end of the 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, when the country began to establish its cultural independence. Some of the leading local artists studied in London under the guidance of the Royal Academy and others, who settled in England, continued to exert influence in their home country through regular submissions of works of art. This was the case with John Singleton Copley, the dominant influence in his country until the beginning of the 19th century, and also with Benjamin West, who became one of the leaders of the English neoclassical-romantic movement and one of the main European names of his generation in the field of history painting. He made a number of fellow disciples, such as Charles Willson Peale, Gilbert Stuart and John Trumbull, and his influence was similar to that of Copley on American painting.[45]

The first academy to be created in the United States was the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, founded in 1805 and still active today. The initiative came from the painter Charles Peale and the sculptor William Rush, along with other artists and traders. Its progress was slow, and its peak was only reached at the end of the 19th century, when it began to receive significant financial support, opened a gallery and formed its own collection, becoming an anti-modernist bastion.[46] The most decisive step toward the formation of an American academic culture was taken when the National Academy of Design was founded in 1826 by Samuel F. B. Morse, Asher B. Durand, Thomas Cole, and other artists dissatisfied with the orientation of the Pennsylvania Academy. It soon became the most respected artistic institution in the country.[47][48] Its method followed the traditional academic model, focusing on drawing from classical and live models, in addition to offering lectures on anatomy, perspective, history and mythology, among other subjects. Cole and Durand were also the founders of the Hudson River School, an aesthetic movement that began a great painting tradition, lasting for three generations, with a remarkable unity of principles, and which presented the national landscape in an epic, idealistic and sometimes fanciful light. Its members included Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, the most celebrated landscape painters of their generation.[49][50]

In the field of sculpture, however, the greatest influence came from the Italian academies, especially through the example of Antonio Canova, who was the main figure of European neoclassicism, educated in part at the Venice Academy and in Rome.[51][52] Italy offered a historical and cultural backdrop of irresistible interest to sculptors, with priceless monuments, ruins and collections, and working conditions were infinitely superior to those of the New World, where there was a shortage of both marble and capable assistants to help the artist in the complex and laborious art of stone carving and bronze casting. Horatio Greenough was just the first in a large wave of Americans to settle between Rome and Florence. The most notable of these was William Wetmore Story, who after 1857 assumed leadership of the American colony that had been created in Rome, becoming a reference for all newcomers. Despite their stay in Italy, the group continued to be celebrated in their country, and their artistic achievements received continuous press coverage until the neoclassical vogue dissipated in North America from the 1870s onwards. By this time, the United States had already established its culture and created the general conditions to promote consistent and high-level local sculptural production, adopting an eclectic synthesis of styles.[53][54][55] These sculptors also strongly absorbed the influence of the French Académie, several of them were educated there, and their production populated most public spaces and the facades of major American buildings, with works of strong civic and great formalism that became icons of local culture, such as the statue of Abraham Lincoln by Daniel Chester French and the memorial to Robert Gould Shaw by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.[56]

In 1875, the Art Students League took over as the leading American art academy, founded by students inspired by the model of the French Académie, establishing the guidelines for national art education until World War II, while also opening its classes to women. Offering better working conditions than its Parisian model, the League was created by artists who saw in the French academic environment an appeal to culture and civilization and believed that this model would discipline the national democratic impulse, transcending regionalisms and social differences, refine the taste of capitalists and contribute to elevating society and improving its culture.[56]

Other countries[edit]

Academic art not only held influence in Western Europe and the United States, but also extended its influence to other countries. The artistic environment of Greece, for instance, was dominated by techniques from Western academies from the 17th century onward: this was first evident in the activities of the Ionian School, and later became especially pronounced with the dawn of the Munich School. This was also true for Latin American nations, which, because their revolutions were modeled on the French Revolution, sought to emulate French culture. An example of a Latin American academic artist is Ángel Zárraga of Mexico. Academic art in Poland flourished under Jan Matejko, who established the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Many of these works can be seen in the Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art at Sukiennice in Kraków.

Academic training[edit]

Teaching principles and cursus[edit]

The academies had as a basic assumption the idea that art could be taught through its systematization into a fully communicable body of theory and practice, minimizing the importance of creativity as an entirely original and individual contribution. Instead, they valued the emulation of established masters, venerating the classical tradition, and adopted collectively formulated concepts that had not only an aesthetic character, but also an ethical origin and purpose.

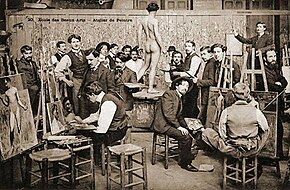

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies", were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of artmaking. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

If approved, they would then draw from plaster casts of famous classical sculptures. Only after acquiring these skills were artists permitted entrance to classes in which a live model posed. Painting was not taught at the École des Beaux-Arts until after 1863. To learn to paint with a brush, the student first had to demonstrate proficiency in drawing, which was considered the foundation of academic painting. Only then could the pupil join the studio of an academician and learn how to paint. Throughout the entire process, competitions with a predetermined subject and a specific allotted period of time measured each student's progress.

The most famous art competition for students was the Prix de Rome, whose winner was awarded a fellowship to study at the Académie française's school at the Villa Medici in Rome for up to five years.[57] To compete, an artist had to be of French nationality, male, under 30 years of age, and single. He had to have met the entrance requirements of the École des Beaux-Arts and have the support of a well-known art teacher. The competition was grueling, involving several stages before the final one, in which 10 competitors were sequestered in studios for 72 days to paint their final history paintings. The winner was essentially assured a successful professional career.

As noted, a successful showing at the Salon, the exhibition of work founded by the École des Beaux-Arts, was a seal of approval for an artist. Artists petitioned the hanging committee for optimal placement "on the line", or at eye level. After the exhibition opened, artists complained if their works were "skyed", or hung too high. The ultimate achievement for the professional artist was election to membership in the Académie française and the right to be known as an academician. This depended on his consistency in exhibitions at the salons and the permanence of his production at a level of excellence.[58]

Women artists[edit]

One effect of the move to academies was to make training more difficult for women artists, who were excluded from most academies until the last half of the 19th century.[a][60][61] This was partly because of concerns over the perceived impropriety presented by nudity during training.[60] In France, for example, the powerful École des Beaux-Arts had 450 members between the 17th century and the French Revolution, of which only 15 were women. Of those, most were daughters or wives of members. In the late 18th century, the French Academy resolved not to admit any women at all.[b] As a result, there are no extant large-scale history paintings by women from this period, though some women like Marie-Denise Villers and Constance Mayer made their name in other genres such as portraiture.[63][64][65][66]

In spite of this, there were important steps forward for female artists. In Paris, the Salon became open to non-Academic painters in 1791, allowing women to showcase their work in the prestigious annual exhibition. Additionally, women were more frequently being accepted as students by famous artists such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Baptiste Greuze.[67]

The emphasis in academic art on studies of the nude remained a considerable barrier for women studying art until the 20th century, both in terms of actual access to the classes and in terms of family and social attitudes to middle-class women becoming artists.[68]

Criticism and legacy[edit]

Decline and the rise of modernism[edit]

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the "false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist Théodule Ribot worked against this by experimenting with rough, unfinished textures in his painting.

Stylistically, the Impressionists, who advocated quickly painting outdoors exactly what the eye sees and the hand puts down, criticized the finished and idealized painting style. Although academic painters began a painting by first making drawings and then painting oil sketches of their subject, the high polish they gave to their drawings seemed to the Impressionists tantamount to a lie, who disavowed the devotion to mechanical techniques.

Realists and Impressionists also defied the placement of still-life and landscape at the bottom of the hierarchy of genres. Most Realists and Impressionists and others among the early avant-garde who rebelled against academism were originally students in academic ateliers. Claude Monet, Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and even Henri Matisse were students under academic artists. Other artists, such as the Symbolist painters and some of the Surrealists, were kinder to the tradition.[citation needed] As painters who sought to bring imaginary vistas to life, these artists were more willing to learn from a strongly representational tradition. Once the tradition had come to be looked on as old-fashioned, the allegorical nudes and theatrically posed figures struck some viewers as bizarre and dreamlike.

As modern art and its avant-garde gained more power, academic art was further denigrated, and seen as sentimental, clichéd, conservative, non-innovative, bourgeois, and "styleless". The French referred derisively to the style of academic art as L'art pompier (pompier means "fireman") alluding to the paintings of Jacques-Louis David (who was held in esteem by the academy), which often depicted soldiers wearing fireman-like helmets.[69] It also suggests half-puns in French with pompéien ("from Pompeii") and pompeux ("pompous").[70][71] The paintings were called "grandes machines", which were said to have manufactured false emotion through contrivances and tricks.

Faced with the dissatisfaction of a growing number of artists excluded from the official salons of the French Academy, in 1863 Emperor Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused), which is considered one of the initial milestones of modernism.[72] Even with this concession, the public reaction was negative,[73] and an anonymous review published at the time summarizes the general attitude:

This exhibition is sad and grotesque... save for one or two questionable exceptions, there is not a single work that deserves the honor of being shown in the official galleries. There is even something cruel about this exhibition, people laugh as if everything was nothing more than a farce.[74]

Following the example of Courbet, who in 1855 had opened a solo exhibition he called the Pavillon du Réalisme (Pavilion of Realism), in 1867 Manet, rejected from the official Salon, exhibited independently, and six years later a group of Impressionists founded the Salon des Indépendants (Salon of Independents). As a result of these initiatives, the art market began to open up to alternative schools, while dealers for new creators and private societies began aggressive campaigns to publicize their own artists, opening up various exhibition spaces to capture the interest of the bourgeois consumer public. Independent critics and literati also played an important role in shifting the economic and social center of gravity of the art system, protecting and promoting various non-academic artists and providing a kind of informal public education through the publication of articles in the press, which became a major forum for artistic debate, and one with a wide reach. In this process, the official institution of the Academy, by then renamed the École des Beaux-Arts and having severed its connection with the government, began to lose ground rapidly, beginning its decline as a consecrating and educational institution.[75][76][77]

Complete denigration and fall into obscurity[edit]

British art critic Clive Bell, linked to the Bloomsbury Group of English modernism, stated in 1914 that, by the middle of the 19th century, art had "died", losing all its aesthetic interest, and even tradition had ceased to exist.[78] This denigration of academic art reached its peak through the writings of American art critic Clement Greenberg who stated in 1939 that all academic art is "kitsch", in the sense of banal, commercialist, and tried to associate academicism with the problems of industrial capitalism, in addition to linking a new concept of "good taste" with the ethics of left-wing, anti-bourgeois political radicalism. For him, the avant-garde was positive because it was an affective expression of a libertarian social conscience, and was therefore truer and freer, which was repeated ad infinitum afterwards, following the logic: academic = reactionary = bad, versus avant-garde = radical = good.[79][80]

Several other influential critics, such as Herbert Read and Ernst Gombrich, devoted great efforts to breaking away from traditional academic standards. In all matters of teaching, not just in art teaching, great importance was given to creativity as the starting point for the learning process, preaching the abandonment of rules and formalisms, and aligning themselves with the proposals of educators and educational philosophers such as Maria Montessori and Jean-Ovide Decroly. Even several of the most important modern artists, such as Kandinsky, Klee, Malevich and Moholy-Nagy, dedicated themselves to creating schools and formulating new theories for art education based on these ideas, most notably the Bauhaus, founded in Weimar, Germany, in 1919 by Walter Gropius. For modernists, creativity was an innate faculty of perception and imagination, possessed by all people, and the less it was influenced by theories and norms, the richer and more fertile it would be. In this context, art education simply aimed to provide the means for this free creativity, guided by feelings and emotions, to be expressed materially as a work of art, a unique and original form that had its own syntax and did not depend on previous references.[81]

Mannerist, Baroque, Rococo and neoclassical academic production managed to pass relatively unscathed by modernist criticism and secure its place in history, but eclectic academic trends of the second half of the 19th century were ridiculed and devalued to the point that, throughout the 20th century, most of these works were discarded from private collections, saw their market prices plummet and were removed from display in museums, relegated to oblivion in their storerooms.[82][83][84] By the 1950s, all the last practitioners of the old academicism had been cast into obscurity. More than that, pure opposition to academicism had become one of the main cohesive forces of the modern movement, and the only thing that interested critics linked to the avant-garde was the avant-garde itself.[85]

Critical recovery[edit]

Despite the widespread discredit into which academicism fell, several researchers throughout the 20th century undertook the study of the academic phenomenon. Art historian Paul Barlow stated that despite the wide dissemination of modernism at the beginning of the 20th century, the theoretical bases of its rejection of academicism were surprisingly little explored by its proponents, forming above all a kind of "anti-academic myth", more than a consistent critique.[86] Of all those engaged in this study, Nikolaus Pevsner was perhaps the most important, describing in the 1940s the history of academies on an epic scale, but focusing on the institutional and organizational aspects, disconnecting them from the aesthetic and geographical ones.[87]

Since the early 1990s, the creation of academic art has even experienced a limited resurgence through the Classical Realist atelier movement.[88] In museums and art galleries, L'art pompier (a term supporters mostly avoid) has also enjoyed something of a critical revival, partly caused by the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, where it is displayed on more equal terms with the Impressionists and Realist painters of the period. The opening of this museum in 1986 did not go without heated debate in France, as it was seen by some critics as a rehabilitation of academicism, or even "revisionism".[89] The art historian André Chastel, however, considered as early as 1973 that there were "nothing but advantages in replacing a global judgment of disapproval, the legacy of old battles, with a quiet and objective curiosity." Some other institutional agents of this rescue are the Dahesh Museum of Art in the United States, which specializes in academic art of the 19th and 20th centuries,[82] as well as the Art Renewal Center, also based in the United States and dedicated to promoting academicism as a basis for the qualified training of future masters.[90] Additionally, the art is gaining a broader appreciation by the public at large, and whereas academic paintings once would only fetch a few hundreds of dollars in auctions, some now fetch millions.[91]

Major artists[edit]

Austria[edit]

Belgium[edit]

Brazil[edit]

Canada[edit]

Croatia[edit]

Czech Republic[edit]

Estonia[edit]

Finland[edit]

France[edit]

|

Germany[edit]

Hungary[edit]

India[edit]

Ireland[edit]

Italy[edit]

Latvia[edit]

Netherlands[edit]

Peru[edit]

Poland[edit]

Russia[edit]

Serbia[edit]

Slovenia[edit]

Spain[edit]

Sweden[edit]

Switzerland[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

Uruguay[edit]

|

Gallery[edit]

-

The Rape of the Sabine Women, by Nicolas Poussin, c. 1634–35, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Egypt Saved by Joseph, by Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol, 1827, oil on canvas, ceiling of a room in the Louvre Palace, Paris[93]

-

The Assassination of the Duke of Guise at the Château de Blois in 1588, by Paul Delaroche, 1834, oil on canvas, Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

-

Condé and Mazarin, by Eugène Devéria, c. 1835, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, Orléans, France

-

The Romans in their Decadence, by Thomas Couture, 1844–1847, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris[94]

-

Call of the Last Victims of Terror, by Charles Louis Müller, 1850, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne, Carcassonne, France

-

The Alchemist, by William Fettes Douglas, 1853, oil on canvas, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[95]

-

The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1855, oil on canvas, Château de Compiègne, Compiègne, France[96]

-

Rehearsal of The Flute Player and The Woman of Diomede at the home of Prince Napoleon in the atrium of his Pompeian house, by Gustave Boulanger, 1861, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay

-

Lost Illusions, by Léon Dussart and Charles Gleyre, 1865–1867, oil on canvas, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, US

-

The Death of Orpheus, by Émile Lévy, 1866, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[97]

-

The Discovery of Pulque, by Jose Maria Obregon, 1869, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

-

Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1872, oil on canvas, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

-

The Triumph of Beauty, Charmed by Music, amidst the Muses and the Hours of the Day, designed for the ceiling of the auditorium of the Palais Garnier, by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu, 1872, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay

-

Moonlit Dreams, by Gabriel Ferrier, 1874, oil on canvas, private collection

-

The Excommunication of Robert the Pious, by Jean-Paul Laurens, 1875, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[99]

-

The Babylonian Marriage Market, by Edwin Long, 1875, oil on canvas, Royal Holloway, University of London

-

Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners, by Alexandre Cabanel, 1887, oil on canvas, private collection[101]

-

The Renaissance of Letters, by Pierre-Victor Galland, 1888, oil on canvas, Musée départemental de l'Oise, Beauvais, France

-

Ulysses and the Sirens, by John William Waterhouse, 1891, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia[102]

-

The Garden of the Hesperides, by Frederic Leighton, c. 1892, oil on canvas, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Wirral, the UK[103]

-

Reverie (In the Days of Sappho), by John William Godward, 1904, oil on canvas, Getty Center

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Royal Academy did not admit women until 1861, despite having two, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, among its founding members, as evidenced by the group portrait of The Academicians of the Royal Academy by Johan Zoffany, now in the Royal Collection. In it, only the men of the Academy are assembled in a large artist studio, together with nude male models. For reasons of decorum given the nude models, the two women are not shown as present, but as portraits on the wall instead.[59]

- ^ It was only in 1897 that the École des Beaux-Arts officially accepted women. They were then authorized to work in the galleries, to sit the entrance exams and to take painting and sculpture classes in a separate studio from the men. This date of 1897 initially concerned the painting section, but was extended to the architecture section in 1898 and the sculpture section in 1899. In 1900, women were given access to the studios, which allowed them to paint live models.[62]

References[edit]

- ^ Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (in Italian). Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo: Direzione Generale per le Biblioteche, gli Istituti Culturali e il Diritto d'Autore. Accessed October 2014.

- ^ Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Santi di Tito and the Florentine Academy: Solomon Building the Temple in the Capitolo of the Accademia del Disegno (1570–71), Apollo CLV, 480 (February 2002): p. 31–39

- ^ Adorno, Francesco. (1983). Accademie e istituzioni culturali a Firenze (in Italian). Florence: Olschki.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus. Academies of Art: Past and Present. The University Press, 1940. p. 110–111

- ^ Carl Goldstein (1996). Teaching Art: Academies and Schools from Vasari to Albers. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55988-X.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus. Academies of Art: Past and Present. The University Press, 1940. p. 118–119

- ^ Claudio Strinati, Annibale Carracci (in Italian), Firenze, Giunti Editore, 2001 ISBN 88-09-02051-0

- ^ Duro, Paul. Academic Theory: 1550-1800. In Smith, Paul & Wilde, Carolyn. A companion to art theory. Wiley-Blackwell, 2002. p. 89–90

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy. The sociology of art: a reader. Routledge, 2003. p. 4

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus. Academies of Art: Past and Present. The University Press, 1940. p. 97–98

- ^ Yates, Frances Amelia. The French academies of the sixteenth century. Taylor & Francis, 1988. p. 140–140, 275–279

- ^ Testelin 1853, p. 22–36.

- ^ Montaiglon & Cornu 1875, p. 7–10.

- ^ Dussieux et al. 1854, p. 216.

- ^ Janson, H.W. (1995). History of Art, 5th edition, revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500237018

- ^ a b Barasch, Moshe. Theories of Art: From Plato to Winckelmann. Routledge, 2000. p. 330–333

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O Sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. p. 65–66

- ^ Driskel, Michael Paul. Representing belief: religion, art, and society in nineteenth-century France, Volume 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992. p. 47–49

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy. The sociology of art: a reader. Routledge, 2003. p. 5

- ^ Hodgson & Eaton 1905, p. 11.

- ^ John Harris, Sir William Chambers Knight of the Polar Star, Chapter 11: The Royal Academy, 1970, A. Zwemmer Ltd

- ^ J. Wadum, M. Scharff, K. Monrad, "Hidden Drawings from the Danish Golden Age. Drawing and underdrawing in Danish Golden Age views from Italy" in SMK Art Journal 2006, ed. Peter Nørgaard Larsen. Statens Museum for Kunst, 2007.

- ^ a b Kemp, Martín. The Oxford history of Western art. Oxford University Press US, 2000, p. 218–219

- ^ Eulálio, Alexandre. O Século XIX. In Tradição e Ruptura. Síntese de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 1984–85, p. 121

- ^ a b c Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O Sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. p. 70–72

- ^ Ledbury, Mark. Denis Diderot. In Murray, Chris. Key Writers on Art: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Routledge, 2003. p. 108–109

- ^ Lavin, Sylvia. Quatremère de Quincy and the invention of a modern language of architecture. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1992. p. 159–167

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O Sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. p. 118–119

- ^ Barasch, Moshe. Theories of Art: From Plato to Winckelmann. Routledge, 2000. p. 333–334

- ^ a b c Hierarchy of the Genres. Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art

- ^ a b c Kemp, Martín. The Oxford history of Western art. Oxford University Press US, 2000. p. 218–219

- ^ Rosenblum, Robert. Transformations in late eighteenth century art. Princeton University Press, 1970. p. 102–103

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O Sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. p. 117–118, 142–144

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy. The sociology of art: a reader. Routledge, 2003. p. 5

- ^ Collingwood, W. G. The Art Teaching of John Ruskin. Read Books, 2008. p. 73–74

- ^ Doy, Gen. Hidden from Histories: women history painters in the early ninetheenth-century France. In Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 71–85

- ^ a b Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. Toward a geography of art. University of Chicago Press, 2004. p. 54–55

- ^ Kino, Carol (4 March 2004). "Returning the gaze". The National (Abu Dhabi). Archived from the original on 26 April 2024.

- ^ Patricia Mainardi: The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic, Cambridge University Press, 1993

- ^ Fae Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators: The Paris Salons and the Modern Art Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013

- ^ a b Fyfe, Gordon. Auditing the RA: official discourse and the ninetheenth-century Royal Academy. in Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 117–128

- ^ a b Barlow, Paul. Fear and loathing of the academic, or just what is it that makes the avant-garde so different, so appealing? in Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century]. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 17

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy. The sociology of art: a reader. Routledge, 2003. p. 5–7

- ^ Vaugham, William. Cultivation and Control: the "Masterclass" and the Düsseldorf Academy in the nineteenth centrury. Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 150–152

- ^ Jaffee, David. Art and Identity in the British North American Colonies, 1700–1776. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- ^ Hamilton, John McLure. Men I Have Painted. London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., 1921, p. 176–180

- ^ Jaffee, David. Post-Revolutionary America: 1800–1840. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

- ^ Dulap, William. A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States. C. E. Goodspeed & Co., 1918. Vol. 3, p. 52–57

- ^ Avery, Kevin J. The Hudson River School. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

- ^ Caffin, Charles H. The Story of American Painting. Kessinger Publishing, 1999. p. 76–77

- ^ Carmel-Arthur, Judith. Canova and Scarpa in Possagno. In Bryant, Richard; Carmel-Arthur, Judith & Scarpa, Carlo (eds). Carlo Scarpa: Museo Canoviano, Possagno. Volume 22 de Opus Series. Axel Menges, 2002. p. 6–12

- ^ Cicognara, conde Leopoldo. Biographical Memoir. In Bohn, Henry G. (ed). The Works of Antonio Canova, in Sculpture and Modelling, engraved in Outline by Henry Moses; with Descriptions by Countess Albrizzi, and a Biographical Memoir by Count Cicognara. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1823. Vol. I, pp. i-vi

- ^ Tolles, Thayer. American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- ^ Tolles, Thayer. American Bronze Casting. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- ^ Peck, Amelia. American Revival Styles, 1840–1876. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- ^ a b Scott, William B. & Rutkoff, Peter M. New York Modern: The Arts and the City. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. p. 8–9

- ^ "Prix de Rome". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 November 2023.

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O Sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. p. 66–68

- ^ Zoffany, Johan (1771–1772). "The Royal Academicians". The Royal Collection. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ a b Myers, Nicole. "Women Artists in Nineteenth–Century France". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Levin, Kim (November 2007). "Top Ten ARTnews Stories: Exposing the Hidden 'He'". ArtNews.

- ^ Marina Sauer, L'entrée des femmes à l'Ecole des Beaux-Arts, 1880-1923 (in French), Paris, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1990, p. 10

- ^ Harris, Ann Sutherland and Linda Nochlin. Women Artists: 1550–1950. Alfred A. Knopf, New York (1976). p. 217

- ^ Petteys, Chris, Dictionary of Women Artists, G K Hill & Co. publishers, 1985

- ^ Delia Gaze. Concise Dictionary of Women Artists. Routledge; 3 April 2013. ISBN 978-1-136-59901-9. p. 665

- ^ Germaine Greer. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work. Tauris Parke Paperbacks; 2 June 2001. ISBN 978-1-86064-677-5. p. 36–37

- ^ Stranahan, C.H., "A History of French Painting: An account of the French Academy of Painting, its salons, schools of instructions and regulations", Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1896

- ^ Nochlin, Linda. "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" (PDF). Department of Art History, University of Concordia.

- ^ Louis-Marie Descharny, L'Art pompier (in French), 1998, p. 12

- ^ Louis-Marie Descharny, L'Art pompier (in French), 1998, p. 14

- ^ Pascal Bonafoux, Dictionnaire de la peinture par les peintres (in French), p. 238–239, Perrin, Paris, 2012 ISBN 978-2-262-032784 (read online).

- ^ Boime, Albert (1969). "The Salon des Refusés and the Evolution of Modern Art". Art Quarterly. 32.

- ^ Maneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial – la vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, (in French), Éditions Armand Colin, (1990). p. 173

- ^ Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Introduction: academic narratives. In Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 2–3

- ^ Kleiner, Fred. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Cengage Learning, 2009. Vol. II, 13th ed. p. 655

- ^ Alexander, Victoria D. Sociology of the arts: exploring fine and popular forms. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003. p. 83–86

- ^ Elkins, James. Second Roundtable In Elkins, James & Newman, Michael (eds). The state of art criticism. Routledge, 2007. p. 243–244

- ^ Bell, Clive. Art. BiblioBazaar, LLC, reprint of 2007. p. 114

- ^ Greenberg, Clement & John O'Brian (editor). The Collected Essays and Criticism: Modernism with a vengeance, 1957-1969. University of Chicago Press, 1995. p. 299

- ^ Barlow, Paul. Fear and loathing of the academic, or just what is it that makes the avant-garde so different, so appealing? in Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century]. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 18

- ^ De Duve, Thierry. When Form Has Become Attitude - And Beyond. In Kocur, Zoya & Leung, Simon. Theory in contemporary art since 1985. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005. p. 20–21

- ^ a b Farmer, J. David. Foreword in Weisberg, Gabriel P. Against the modern: Dagnan-Bouveret and the transformation of the academic tradition. Rutgers University Press, 2002. pp. xi-xii

- ^ Thompson, James Matheson. Twentieth century theories of art. McGill-Queen's Press, 1990. p. 101–102

- ^ Denis, Rafael & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 9

- ^ Kulka, Tomáš. Kitsch and art. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996. p. 60

- ^ Barlow, Paul. Fear and loathing of the academic, or just what is it that makes the avant-garde so different, so appealing? in Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century]. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 16–17

- ^ Denis, Rafael & Trodd, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. p. 3–5

- ^ Panero, James: "The New Old School", The New Criterion, Volume 25, September 2006, p. 104

- ^ Harding, p. 14–22

- ^ Ross, Fred. The ARC Philosophy. Published on 1 January, 2002. Art Renewal Center

- ^ Esterow, Milton (1 January 2011). "From 'Riches to Rags to Riches'". ArtNews. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Academism of the 19th Century". www.galerijamaticesrpske.rs. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 110. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- ^ Graham-Nixon, Andrew (2023). art THE DEFINITIVE VISUAL HISTORY. DK. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-2416-2903-1.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2020). The Art of the Occult - A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic. White Lion Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978 0 7112 4883 0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Christophe, Averty (2020). Orsay. Éditions Place des Victories. p. 40. ISBN 978-2-8099-1770-3.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Christophe, Averty (2020). Orsay. Éditions Place des Victories. p. 41. ISBN 978-2-8099-1770-3.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2020). The Art of the Occult - A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic. White Lion Publishing. p. 215. ISBN 978 0 7112 4883 0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2022). The Art of Darkness. White Lion Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-0 7112-6920-0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

Bibliography[edit]

- Dussieux, Louis Etienne; Soulié, Eudore; Mantz, Paul; Montaiglon, Anatole de (1854). Mémoires inédits sur la vie et les ouvrages des membres de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture : publiés d'après les manuscrits conservés à l'Ecole impériale des beaux-arts [Unpublished memoirs on the life and works of members of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture: published from the manuscripts kept at the Imperial School of Fine Arts] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: J.-B. Dumoulin. (Vol. 1 and 2 at Internet Archive, Vol. 1 and 2 at Gallica.)

- Harding, James. Artistes pompiers: French academic art in the 19th century, New York: Rizzoli, 1979.

- Hodgson, J. E.; Eaton, Fred A. (1905). The Royal academy and its members 1768–1830. London: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Montaiglon, Anatole de; Cornu, M. Paul (1875). Table Procès-Verbaux de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, 1648-1793 [Table Minutes of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, 1648-1793] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: J. Baur.

- Testelin, Henri (1853). Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, depuis 1648 jusqu'en 1664 [Memories to serve in the history of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture from 1648 until 1664] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: P. Jannet.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Art and the Academy in the Nineteenth Century. (2000). Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin (Eds). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2795-3

- L'Art-Pompier (1998). Lécharny, Louis-Marie, Que sais-je? (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-049341-6

- L'Art pompier: immagini, significati, presenze dell'altro Ottocento francese (1860–1890) (in French). (1997). Luderin, Pierpaolo, Pocket library of studies in art, Olschki. ISBN 88-222-4559-8

External links[edit]

Media related to Academic art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Academic art at Wikimedia Commons

![Egypt Saved by Joseph, by Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol, 1827, oil on canvas, ceiling of a room in the Louvre Palace, Paris[93]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Abel_de_Pujol_plafond_1827.jpg/389px-Abel_de_Pujol_plafond_1827.jpg)

![The Romans in their Decadence, by Thomas Couture, 1844–1847, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris[94]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/THOMAS_COUTURE_-_Los_Romanos_de_la_Decadencia_%28Museo_de_Orsay%2C_1847._%C3%93leo_sobre_lienzo%2C_472_x_772_cm%29.jpg/427px-THOMAS_COUTURE_-_Los_Romanos_de_la_Decadencia_%28Museo_de_Orsay%2C_1847._%C3%93leo_sobre_lienzo%2C_472_x_772_cm%29.jpg)

![The Alchemist, by William Fettes Douglas, 1853, oil on canvas, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[95]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/William_Fettes_Douglas_-_The_Alchemist.jpg/193px-William_Fettes_Douglas_-_The_Alchemist.jpg)

![The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1855, oil on canvas, Château de Compiègne, Compiègne, France[96]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Winterhalter_Franz_Xavier_The_Empress_Eugenie_Surrounded_by_her_Ladies_in_Waiting.jpg/368px-Winterhalter_Franz_Xavier_The_Empress_Eugenie_Surrounded_by_her_Ladies_in_Waiting.jpg)

![The Death of Orpheus, by Émile Lévy, 1866, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[97]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Death_of_Orpheus_by_%C3%89mile_L%C3%A9vy_%281866%29.jpg/161px-Death_of_Orpheus_by_%C3%89mile_L%C3%A9vy_%281866%29.jpg)

![Gloria Victis, by Antonin Mercié, 1874, bronze, Petit Palais, Paris[98]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/78/Gloria_Victis%2C_PPS3351%281%29%284%29.jpg/190px-Gloria_Victis%2C_PPS3351%281%29%284%29.jpg)

![The Excommunication of Robert the Pious, by Jean-Paul Laurens, 1875, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[99]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Excommunication_de_Robert_le_Pieux-Jean-Paul_Laurens-IMG_8140.JPG/383px-Excommunication_de_Robert_le_Pieux-Jean-Paul_Laurens-IMG_8140.JPG)

![The Oracle, by Camillo Miola, 1880, oil on canvas, Getty Center, Los Angeles, US[100]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Camillo_Miola_%28Biacca%29_-_The_Oracle_-_72.PA.32_-_J._Paul_Getty_Museum.jpg/337px-Camillo_Miola_%28Biacca%29_-_The_Oracle_-_72.PA.32_-_J._Paul_Getty_Museum.jpg)

![Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners, by Alexandre Cabanel, 1887, oil on canvas, private collection[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Alexandre_Cabanel_-_Cl%C3%A9opatre_essayant_des_poisons_sur_des_condamn%C3%A9s_%C3%A0_mort.jpg/445px-Alexandre_Cabanel_-_Cl%C3%A9opatre_essayant_des_poisons_sur_des_condamn%C3%A9s_%C3%A0_mort.jpg)

![Ulysses and the Sirens, by John William Waterhouse, 1891, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia[102]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/WATERHOUSE_-_Ulises_y_las_Sirenas_%28National_Gallery_of_Victoria%2C_Melbourne%2C_1891._%C3%93leo_sobre_lienzo%2C_100.6_x_202_cm%29.jpg/521px-WATERHOUSE_-_Ulises_y_las_Sirenas_%28National_Gallery_of_Victoria%2C_Melbourne%2C_1891._%C3%93leo_sobre_lienzo%2C_100.6_x_202_cm%29.jpg)

![The Garden of the Hesperides, by Frederic Leighton, c. 1892, oil on canvas, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Wirral, the UK[103]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a3/Frederic_Leighton_-_The_Garden_of_the_Hesperides.jpg/256px-Frederic_Leighton_-_The_Garden_of_the_Hesperides.jpg)