English Electric Lightning

| Lightning | |

|---|---|

Lightning F.6 of No. 11 Squadron RAF arriving at RAF Greenham Common in 1976. | |

| General information | |

| Type | Interceptor (primary); fighter |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 337 (including prototypes)[1] |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 11 July 1960[2] (frontline service) |

| First flight |

|

| Retired | 30 April 1988 (RAF)[3] |

The English Electric Lightning is a British fighter aircraft that served as an interceptor during the 1960s, the 1970s and into the late 1980s. It is capable of a top speed of above Mach 2. The Lightning was designed, developed, and manufactured by English Electric. After EE merged with other aircraft manufacturers to form the British Aircraft Corporation it was marketed as the BAC Lightning. It was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF), the Kuwait Air Force (KAF), and the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF).

A unique feature of the Lightning's design is the vertical, staggered configuration of its two Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet engines within the fuselage. The Lightning was designed and developed as an interceptor to defend the airfields of the British "V bomber" strategic nuclear force[4] from attack by anticipated future nuclear-armed supersonic Soviet bombers such as what emerged as the Tupolev Tu-22 "Blinder", but it was subsequently also required to intercept other bomber aircraft such as the Tupolev Tu-16 ("Badger") and the Tupolev Tu-95 ("Bear").

The Lightning has exceptional rate of climb, ceiling, and speed; pilots have described flying it as "being saddled to a skyrocket".[1] This performance and the initially limited fuel supply meant that its missions are dictated to a high degree by its limited range.[5] Later developments provided greater range and speed along with aerial reconnaissance and ground-attack capability. Overwing fuel tank fittings were installed in the F6 variant and gave an extended range, but limited maximum speed to a reported 1,000 miles per hour (1,600 km/h).[6]

Following retirement by the RAF on 30 April 1988,[3] many of the remaining aircraft became museum exhibits. Until 2009, three Lightnings were kept flying at Thunder City in Cape Town, South Africa. In September 2008, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers conferred on the Lightning its Engineering Heritage Award at a ceremony at BAE Systems (the successor to BAC) Warton Aerodrome.[7]

Development

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The specification for the aircraft followed the cancellation of the Air Ministry's 1942 specification E.24/43 supersonic research aircraft which had resulted in the Miles M.52 programme.[8] Teddy Petter, formerly chief designer at Westland Aircraft, who had been taken on by English Electric in 1944 to head an office to develop aircraft rather than just make other manufacturers' designs, was a keen early proponent of Britain's need to develop a supersonic fighter aircraft. In 1947, Petter approached the Ministry of Supply (MoS) with his proposal, and in response Specification ER.103 was issued for a single research aircraft, which was to be capable of flight at Mach 1.5 (1,593 km/h; 990 mph) and 50,000 ft (15,000 m).[9]

Petter initiated a design proposal with Frederick Page[a] leading the design and Ray Creasey[b] responsible for the aerodynamics.[10] By July 1948 their proposal incorporated the stacked engine configuration and a high-mounted tailplane. As it was designed for Mach 1.5, the wing leading edge was swept back 40° to keep it clear of the Mach cone.[11] This proposal was submitted in November 1948,[12] and in January 1949 the project was designated P.1 by English Electric.[citation needed] On 29 March 1949 the MoS granted approval to start the detailed design, develop wind tunnel models and build a full-size mockup.[12]

The design that had developed during 1948 evolved further during 1949 to further improve performance, taking many design cues from the CAC CA-23. [10] To achieve Mach 2 the wing sweep was increased to 60° with the ailerons moved to the wingtips.[13] In late 1949, low-speed wind tunnel tests showed that a vortex was generated by the wing which caused a large downwash on the tailplane; this issue was solved by lowering the tail below the wing.[13] Following the resignation of Petter from English Electric, Page took over as design team leader for the P.1[14] and the running of EE design office. In 1949, the Ministry of Supply had issued Specification F23/49, which expanded upon the scope of ER103 to include fighter-level manoeuvring. On 1 April 1950, English Electric received a contract for two flying airframes, as well as one static airframe, designated P.1.[15]

The Royal Aircraft Establishment disagreed with Petter's choice of sweep angle (60 degrees) and tailplane position (low) considering it to be dangerous. To assess the effects of wing sweep and tailplane position on the stability and control of Petter's design Short Brothers were issued a contract by the Ministry of Supply to produce the Short SB.5 in mid-1950.[16] This was a low-speed research aircraft that could test sweep angles from 50 to 69 degrees and high or low tailplane positions. Testing with the wings and tail set to the P.1 configuration started in January 1954 and confirmed this combination as the correct one.[17]

Prototypes

[edit]

From 1953 onward, the first three prototype aircraft were hand-built at Samlesbury Aerodrome, where all Lightnings were built.[18] These aircraft were given the aircraft serials WG760, WG763, and WG765 (the structural test airframe).[19] The prototypes were powered by un-reheated Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojets, as the selected Rolls-Royce Avon engines had fallen behind schedule due to their own development problems.[20] Since there was no space in the fuselage for fuel the thin wings were the fuel tanks and since they also provided space for the stowed main undercarriage the fuel capacity was relatively small, giving the prototypes an extremely limited endurance, and the narrow tyres housed in the thin wings rapidly wore out if there was any crosswind component during take-off or landing.[21] Outwardly, the prototypes looked very much like the production series, but they were distinguished by the rounded-triangular air intake with no centre-body at the nose, short fin, and lack of operational equipment.[1]

On 9 June 1952, it was decided that there would be a second phase of prototypes built to develop the aircraft toward achieving Mach 2.0 (2,450 km/h; 1,522 mph); these were designated P.1B while the initial three prototypes were retroactively reclassified as P.1A.[22] P.1B was a significant improvement on P.1A. While it was similar in aerodynamics, structure and control systems, it incorporated extensive alterations to the forward fuselage, reheated Rolls-Royce Avon R24R engines, a conical centre body inlet cone, variable nozzle reheat and provision for weapons systems integrated with the ADC and AI.23 radar.[23][24] Three P.1B prototypes were built, assigned serials XA847, XA853 and XA856.[25]

In May 1954, WG760 and its support equipment were moved to RAF Boscombe Down for pre-flight ground taxi trials; on the morning of 4 August 1954, WG760, piloted by Roland Beamont, flew for the first time from Boscombe Down.[26] One week later, WG760 officially achieved supersonic flight for the first time, having exceeded the speed of sound during its third flight.[24] During its first flight, WG760 had unknowingly exceeded Mach 1 (1,225 km/h; 761 mph), but due to position error the Mach meter only showed a maximum of Mach 0.95 (1,164 km/h; 723 mph). The occurrence was noticed during flight data analysis a few days later.[27] While WG760 had proven the P.1 design to be viable, it was limited to Mach 1.51 (1,850 km/h; 1,149 mph) due to directional stability limits. In May 1956, the P.1 received the "Lightning" name, which was said to have been partially selected to reflect the aircraft's supersonic capabilities.[28]

OR.155 and project selection

[edit]In 1955, the Air Ministry learned of the Tupolev Tu-22, expected to enter service in 1962. It could cruise for relatively long periods at Mach 1.2 (1,470 km/h; 913 mph) and had a dash speed of Mach 1.5. Against a target flying at these speeds, the existing Gloster Javelin interceptors would be useless; its primary de Havilland Firestreak armament could only attack from the rear and the Tu-22 would run away from the Javelin in that approach. A faster version, the "thin-wing Javelin", would offer limited supersonic performance and make it marginally useful against the Tu-22, while a new missile, "Red Dean" would allow head-on attacks. This combination would be somewhat useful against Tu-22, but of marginal use if faster bombers were introduced. In January 1955, the Air Ministry issued Operational Requirement F.155 calling for a faster design to be armed with either an improved Firestreak known as "Blue Vesta", or an improved Red Dean known as "Red Hebe". The thin-wing Javelin was cancelled in May 1956.

In March 1957, Duncan Sandys released the 1957 Defence White Paper which outlined the changing strategic environment due to the introduction of ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads. Although missiles of the era had relatively low accuracy compared to a manned bomber, any loss of effectiveness could be addressed by the ever-increasing yield of the warhead. This suggested that there was no targeting of the UK that could not be carried out by missiles, and Sandys felt it was unlikely that the Soviets would use bombers as their primary method of attack beyond the mid-to-late 1960s.

This left only a brief period, from 1957 to some time in the 1960s, in which bombers remained a threat. Sandys felt that the imminent introduction of the Bloodhound Mk. II surface-to-air missile would offer enough protection against bombers. The Air Ministry disagreed; they pointed out that the Tu-22 would enter service before Bloodhound II, leaving the UK open to sneak attack.[29] Sandys eventually agreed this was a problem, but pointed out that F.155 would enter service after Bloodhound, as would a further improved SAM, "Blue Envoy". F.155 was cancelled on 29 March 1957 and Blue Envoy in April.[30]

To fill the immediate need for a supersonic interceptor, Lightning was selected for production. The aircraft was already flying, and the improved P.1B was only weeks away from its first flight. Lightnings mounting Firestreak could be operational years before Bloodhound II, and the aircraft's speed would make it a potent threat against the Tu-22 even in a tail-chase. To further improve its capability, in July 1957 the Blue Vesta program was reactivated in a slightly simplified form, allowing head-on attacks against an aircraft whose fuselage was heated through skin friction while flying supersonically. In November 1957, the missile was renamed "Red Top". This would allow Lightning to attack even faster bombers through a collision-course approach. Thus, what had originally been an aircraft without a mission beyond testing was now selected as the UK's next front-line fighter.

Further testing

[edit]On 4 April 1957 Beamont made the first flight of the P.1B XA847, exceeding Mach 1 during this flight.[27][31] During the early flight trials of the P.1B speeds in excess of 1,000 mph were achieved daily. During this period the Fairey Delta 2 (FD2) held the world speed record of 1,132 miles per hour (1,822 km/h) achieved on 10 March 1956 and held till December 1957. While the P.1B was potentially faster than the FD2, it lacked the fuel capacity to provide one run in each direction at maximum speed to claim the record in accordance with international rules.[32]

In 1958 two test pilots from the USAF Air Force Flight Test Center, Andy Anderson and Deke Slayton, were given the opportunity to familiarise themselves with the P.1B. Slayton, who was subsequently selected as one of the Mercury astronauts, commented:

The P.1 was a terrific plane, with the easy handling of the F-86 and the performance of an F-104. Its only drawback was that it had no range at all... Looking back, however, I'd have to say that the P.1 was my favourite all-time plane.[33]

In late October 1958, the plane was officially and formally named "Lightning".[34] The event was celebrated in traditional style in a hangar at RAE Farnborough, with the prototype XA847 having the name 'Lightning' freshly painted on the nose in front of the RAF Roundel, which almost covered it.[34] A bottle of champagne was put beside the nose on a special smashing rig which allowed the bottle to safely be smashed against the side of the aircraft. The honor of smashing the bottle went to the Chief of the Air Staff, Sir Dermot Boyle.[34]

On 25 November 1958 the P.1B XA847, piloted by Roland Beamont, reached Mach 2 for the first time[35][36] in a British aircraft.[1] This made it the second Western European aircraft to reach Mach 2, the first one being the French Dassault Mirage III just over a month earlier on 24 October 1958.[37]

Production

[edit]The first operational Lightning, designated Lightning F.1, was designed as an interceptor to defend the V Force airfields in conjunction with the "last ditch" Bristol Bloodhound missiles located either at the bomber airfield, e.g. at RAF Marham, or at dedicated missile sites near to the airfield, e.g. at RAF Woodhall Spa near the 3-squadron Vulcan station RAF Coningsby. The bomber airfields along with the dispersal airfields, would be the highest priority targets in the UK for enemy nuclear weapons. To best perform this intercept mission, emphasis was placed on rate-of-climb, acceleration, and speed, rather than range – originally a radius of operation of 150 miles (240 km) from the V bomber airfields was specified – and endurance. It was equipped with two 30 mm ADEN cannon in front of the cockpit windscreen and an interchangeable fuselage weapons pack containing either an additional two ADEN cannon, 48 two-inch (51 mm) unguided air-to-air rockets, or two de Havilland Firestreak air-to-air missiles.[38] The Ferranti AI.23 onboard radar provided missile guidance and ranging, as well as search and track functions.[39]

The next two Lightning variants, the Lightning F.1A and F.2, incorporated relatively minor design changes; for the next variant, the Lightning F.3, they were more extensive. The F.3 had higher thrust Rolls-Royce Avon 301R engines, a larger squared-off fin and strengthened inlet cone allowing a service clearance to Mach 2.0 (2,450 km/h; 1,522 mph) (the F.1, F.1A and F.2 were limited to Mach 1.7 (2,083 km/h; 1,294 mph)).[40] The A.I.23B radar and Red Top missile offered a forward hemisphere attack capability and deletion of the nose cannon. The new engines and fin made the F.3 the highest performance Lightning yet, but with an even higher fuel consumption and resulting shorter range. The next variant, the Lightning F.6, was already in development, but there was a need for an interim solution to partially address the F.3's shortcomings, the Interim F.Mk6.

The Interim F.Mk6 introduced two improvements: a new, non-jettisonable, 610-imperial-gallon (2,800 L) ventral fuel tank,[41] and a new, kinked, conically cambered wing leading edge, incorporating a slightly larger leading edge fuel tank, raising the total usable internal fuel by 716 imperial gallons (3,260 L). The conically cambered wing improved manoeuvrability, especially at higher altitudes, and the ventral tank nearly doubled available fuel. The increased fuel was welcome, but the lack of cannon armament was felt to be a deficiency. It was thought that cannon would be useful in a peacetime interception for firing warning shots to encourage an aircraft to change course or to land.[42]

The Lightning F.6 was originally nearly identical to the F.3A with the exception that it could carry two 260-imperial-gallon (1,200 L) ferry tanks on pylons over the wings. These tanks were jettisonable in an emergency, and gave the F.6 a substantially improved deployment capability. There remained one glaring shortcoming: the lack of cannon. This was finally rectified in the form of a modified ventral tank with two ADEN cannon mounted in the front. The addition of the cannon and their ammunition decreased the tank's fuel capacity from 610 to 535 imperial gallons (2,770 to 2,430 L).[41]

The Lightning F.2A was an F.2 upgraded with the cambered wing, the squared fin, and the 610 imperial gallons (2,800 L) ventral tank. The F.2A retained the A.I.23 and Firestreak missile, the nose cannon, and the earlier Avon 211R engines.[43] Although the F.2A lacked the thrust of the later Lightnings, it had the longest tactical range of all Lightning variants, and was used for low-altitude interception over West Germany.

Export and further developments

[edit]The Lightning F.53, otherwise known as the Export Lightning, was developed as a private venture by BAC. While the Lightning had originated as an interception aircraft, this version was to have a multirole capability for quickly interchanging between interception, reconnaissance, and ground-attack duties.[44] The F.53 was based on the F.6 airframe and avionics, including the large ventral fuel tank, cambered wing and overwing pylons for drop tanks of the F.6, but incorporated an additional pair of hardpoints under the outer wing. These hardpoints could be fitted with pylons for air-to-ground weaponry, including two 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs or four SNEB rocket pods each carrying eighteen 68 mm rockets. A gun pack carrying two ADEN cannons and 120 rounds each could replace the forward part of the ventral fuel tank.[45][c] Alternative, interchangeable packs in the forward fuselage carried two Firestreak missiles, two Red Top missiles, twin retractable launchers for 44× 2-inch (50 mm) rockets, or a reconnaissance pod fitted with five 70 mm Type 360 Vinten cameras.[47]

BAC also proposed clearing the overwing hardpoints for carriage of weapons as well as drop tanks, with additional Matra JL-100 combined rocket and fuel pods (each containing 18 SNEB 68 mm (2.7 in) rockets and 50 imperial gallons (227 L) of fuel) or 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs being possible options. This could give a maximum ground attack weapons load for a developed export Lightning of six 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs or 44 × 2 in (51 mm) rockets and 144 × 68 mm rockets.[48][49] The Lightning T.55 was the export two-seat variant; unlike the RAF two-seaters, the T.55 was equipped for combat duties. The T.55 had a very similar fuselage to the T.5, while also using the wing and large ventral tank of the F.6.[50] The Export Lightning had all of the capability of the RAF's own Lightnings such as exceptional climb rate and agile manoeuvering. The Export Lightning also retained the difficulty of maintenance, and serviceability rates suffered. The F.53 was generally well regarded by its pilots, and its adaptation to multiple roles showed the skill of its designers.[51]

In 1963, BAC Warton was working on the preliminary design of a two-seat Lightning development with a variable-geometry wing, based on the Lightning T.5. In addition to the variable-sweep wing, which was to sweepback between 25 degrees and 60 degrees, the proposed design featured an extended ventral pack for greater fuel capacity, an enlarged dorsal fin fairing, an arrestor hook, and a revised inward-retracting undercarriage. The aircraft was designed to be compatible with the Royal Navy's existing aircraft carriers' carrier-based aircraft, the VG Lightning concept was revised into a land-based interceptor intended for the RAF the following year.[52] Various alternative engines to the Avon were suggested, such as the newer Rolls-Royce Spey engine. It is likely that the VG Lightning would have adopted a solid nose (by moving the air inlet to the sides or to upper fuselage) to install a larger, more capable radar.[53]

Design

[edit]Overview

[edit]The Lightning had several distinctive design features, the primary being the twin-engine arrangement, notched delta wing, and low-mounted tailplane. The vertically stacked and longitudinally staggered engines were the solution devised by Petter to meet the conflicting requirements of minimising frontal area, providing undisturbed engine airflow across a wide speed range, and packaging two engines to provide sufficient thrust to meet performance goals. The unusual over/under configuration allowed for the thrust of two engines, with the drag equivalent to only 1.5 engines mounted side-by-side, a reduction in drag of 25% over more conventional twin-engine installations.[54] The engines were fed by a single nose inlet (with inlet cone), with the flow split vertically aft of the cockpit, and the nozzles tightly stacked, effectively tucking one engine behind the cockpit. The result was a low frontal area, an efficient inlet, and excellent single-engine handling with no problems of asymmetrical thrust. Because the engines were close together, an uncontained failure of one engine was likely to damage the other. If desired, an engine could be shut down in flight and the remaining engine run at a more efficient power setting which increased range or endurance;[55][56] although this was rarely done operationally because there would be no hydraulic power if the remaining engine failed.[57]

Production aircraft were powered by various models of the Avon engine. This power-plant was initially rated as capable of generating 11,250 lbf (50.0 kN) of dry thrust, but when employing the four-stage afterburner this increased to a maximum thrust of 14,430 lbf (64.2 kN). Later models of the Avon featured, in addition to increased thrust, a full-variable reheat arrangement.[58] A special heat-reflecting paint containing gold was used to protect the aircraft's structure from the hot engine casing which could reach temperatures of 600 °C (1,000 °F). Under optimum conditions, a well-equipped maintenance facility took four hours to perform an engine change so specialised ground test rigs were developed to speed up maintenance and remove the need to perform a full ground run of the engine after some maintenance tasks.[59] The stacked engine configuration complicated maintenance work, and the leakage of fluid from the upper engine was a recurring fire hazard.[60] The fire risk was reduced, but not eliminated, following remedial work during development.[61] For removal, the lower No.1 engine was removed from below the aircraft, after removal of the ventral tank and lower fuselage access panels, by lowering the engine down, while the upper No.2 engine was lifted out from above via removable sections in the fuselage top.

The fuselage was tightly packed, leaving no room for fuel tankage or main landing gear. While the notched delta wing lacked the volume of a standard delta wing, each wing contained a fairly conventional three-section main fuel tank and leading-edge tank, holding 312 imp gal (1,420 L); the wing flaps also each contained a 33 imp gal (150 L) fuel tank and an additional 5 imp gal (23 L) was contained in a fuel recuperator, bringing the aircraft's total internal fuel capacity to 700 imp gal (3,200 L). The main landing gear was sandwiched outboard of the main tanks and aft of the leading edge tanks, with the flap fuel tanks behind.[39] The long main gear legs retracted toward the wingtip, necessitating an exceptionally thin main tyre inflated to the high pressure of 330–350 psi (23–24 bar; 2,300–2,400 kPa).[62] On landing the No. 1 engine was usually shut down when taxiing to save brake wear, as keeping both engines running at idle power was still sufficient to propel the Lightning to 80 mph if brakes were not used.[34] Dunlop Maxaret anti-lock brakes were fitted.

The Lightning fuel capacity was increased with a conformal ventral fuel tank. A rocket engine pack containing a Napier Double Scorpion engine and 200 imp gal (910 L) of high-test peroxide (HTP) to drive the rocket turbopump, and act as an oxidiser, was planned to be located in place of the ventral tank and would boost performance if non-afterburning engines were fitted. Fuel for the rocket would come from the aircraft fuel supply. The rocket engine option was cancelled in 1958 when it was established that performance with afterburning Avon engines was acceptable.[63] The ventral store was routinely used as an extra fuel tank, holding 247 imp gal (1,120 L) of usable fuel.[39] On later variants of the Lightning, a ventral weapons pack could be installed to equip the aircraft alternatively with different armaments, including missiles, rockets, and cannons.[64]

Avionics and systems

[edit]

Early versions of the Lightning were equipped with the Ferranti-developed AI.23 monopulse radar, which was contained right at the front of the fuselage within an inlet cone at the centre of the engine intake. Radar information was displayed on an early head-up display and managed by onboard computers.[65] The AI.23 supported several operational modes, which included autonomous search, automatic target tracking, and ranging for all weapons; the pilot attack sight provided gyroscopically-derived lead angle and backup stadiametric ranging for gun firing.[39] The radar and gunsight were collectively designated the AIRPASS, for "Airborne Interception Radar and Pilot Attack Sight System". The radar was successively upgraded with the introduction of more capable Lightning variants, such as to provide guidance for the Red Top missile.[66]

The cockpit of the Lightning was designed to meet the RAF's OR946 specification for tactical air navigation technology, and thus featured an integrated flight instrument display arrangement, an Elliott Bros (London) Ltd[67] auto-pilot, a master reference gyroscopic reader, an auto-attack system, and an instrument landing system.[68] Despite initial scepticism of the aircraft's centralised detection and warning system, the system proved its merits during the development program and was redeveloped for greater reliability.[69] Communications included UHF and VHF radios and a datalink.[70] Unlike the previous generation of aircraft which used gaseous oxygen for lifesupport, the Lightning employed liquid oxygen-based apparatus for the pilot; cockpit pressurisation and conditioning was maintained through tappings from the engine compressors.[71]

Electricity was provided via a bleed air-driven turbine housed in the rear fuselage, which drove an AC alternator and DC generator. This approach was unusual, since most aircraft used driveshaft-driven generators/alternators for electrical energy. A 28V DC battery provided emergency backup power. Aviation author Kev Darling stated of the Lightning: "Never before had a fighter been so dependent upon electronics".[72] Each engine was equipped with a pair of hydraulic pumps, one of which powered the flight-control systems and the other power for the undercarriage, flaps, and airbrakes. Switchable hydraulic circuits were used for redundancy in the event of a leak or other failure. A combination of Dunlop Maxaret[57] anti-skid brakes on the main wheels and an Irvin Air Chute[73] braking parachute slowed the aircraft during landing. A tailhook was also fitted.[74] Accumulators on the wheel brakes performed as backups to the hydraulics, providing minimal braking.[75] Above a certain airspeed a stopped engine would 'windmill', that is, continue to be rotated by air flowing through it in a similar manner to a ram air turbine, sufficient to generate adequate hydraulic power for the powered controls during flight.[67]

Toward the end of its service, the Lightning was increasingly outclassed by newer fighters, mainly due to avionics and armament obsolescence. The radar had a limited range and no track while scanning capability, and it could detect targets only in a narrow (40°) arc. While an automatic collision course attack system was developed and successfully demonstrated by English Electric, it was not adopted due to cost concerns.[76][77] Plans were mooted to supplement or replace the obsolete Red Top and Firestreak missiles with modern AIM-9L Sidewinder missiles to help rectify some of the obsolescence, but these ambitions were not realised due to lack of funding.[76][78] An alternative to the modernisation of existing aircraft would have been the development of more advanced variants; a proposed variable-sweep wing Lightning would have likely involved the adoption of a new powerplant and radar and was believed by BAC to significantly increase performance, but ultimately was not pursued.[53]

Climb performance

[edit]Lightning, was designed...as an intercepter fighter. As such, it has probably the fastest rate-of-climb of any combat aircraft – Flight International, 21 March 1968[79]

The Lightning possessed a remarkable climb rate. It was famous for its ability to rapidly rotate from takeoff to climb almost vertically from the runway, though this did not yield the best time-to-altitude. The Lightning's trademark tail-stand manoeuvre exchanged airspeed for altitude; it could slow to near-stall speeds before commencing level flight. The Lightning's optimum climb profile required the use of afterburners during takeoff. Immediately after takeoff, the nose would be lowered for rapid acceleration to 430 knots (800 km/h; 490 mph) IAS before initiating a climb, stabilising at 450 knots (830 km/h; 520 mph). This would yield a constant climb rate of approximately 20,000 ft/min (100 m/s).[62][d] Around 13,000 ft (4,000 m) the Lightning would reach Mach 0.87 (1,009 km/h; 627 mph) and maintain this speed until reaching the tropopause, 36,000 ft (11,000 m) on a standard day.[e] If climbing further, pilots would accelerate to supersonic speed at the tropopause before resuming the climb.[41][62] A Lightning flying at optimum climb profile would reach 36,000 ft (11,000 m) in under three minutes.[62]

The official ceiling of the Lightning was kept secret. Low security RAF documents often stated "in excess of 60,000 ft (18,000 m)". In September 1962, RAF Fighter Command organised interception trials on Lockheed U-2As at heights of around 60,000–65,000 ft (18,000–20,000 m), which were temporarily based at RAF Upper Heyford to monitor Soviet nuclear tests.[80][81][82] Climb techniques and flight profiles were developed to put the Lightning into a suitable attack position. To avoid risking the U-2, the Lightning was not permitted any closer than 5,000 ft (1,500 m) and could not fly in front of the U-2. For the intercepts, four Lightning F1As conducted 18 solo sorties. The sorties proved that, under GCI, successful intercepts could be made at up to 65,000 ft (20,000 m). Due to sensitivity, details of these flights were deliberately avoided in the pilot log books.[83][page needed]

In 1984, during a NATO exercise, Flight lieutenant Mike Hale intercepted a U-2 at a height which they had previously considered safe (thought to be 66,000 feet (20,000 m)). Records show that Hale also climbed to 88,000 ft (27,000 m) in his Lightning F.3 XR749. This was not sustained level flight but a ballistic climb, in which the pilot takes the aircraft to top speed and then puts the aircraft into a climb, exchanging speed for altitude. Hale also participated in time-to-height and acceleration trials against Lockheed F-104 Starfighters from Aalborg. He reports that the Lightnings won all races easily with the exception of the low-level supersonic acceleration, which was a "dead heat".[84] Lightning pilot and Chief Examiner Brian Carroll reported taking a Lightning F.53 up to 87,300 feet (26,600 m) over Saudi Arabia at which level "Earth curvature was visible and the sky was quite dark", noting that the engines were "touchy" in terms of staying lit in the thin air, and "getting down to a more reasonable and sane altitude needed delicate handling."[85]

Carroll compared the Lightning and the McDonnell Douglas F-15C Eagle, having flown both aircraft, stating that: "Acceleration in both was impressive, you have all seen the Lightning leap away once brakes are released, the Eagle was almost as good, and climb speed was rapidly achieved. Takeoff roll is between 2,000 and 3,000 ft [610 and 910 m], depending upon military or maximum afterburner-powered takeoff. The Lightning was quicker off the ground, reaching 50 ft [15 m] height in a horizontal distance of 1,630 ft [500 m]". Chief test pilot for the Lightning Roland Beamont, who also flew most of the "Century Series" US aircraft, stated his opinion that nothing at that time had the inherent stability, control, and docile handling characteristics of the Lightning throughout the full flight envelope. The turn performance and buffet boundaries of the Lightning were well in advance of anything known to him.[86][page needed]

Aircraft performance

[edit]Early Lightning models, the F.1, F.1A, and F.2, had a maximum speed of Mach 1.7 (1,815 km/h; 1,128 mph) at 36,000 feet (11,000 m) in an ICAO standard atmosphere, and 650 knots (1,200 km/h; 750 mph) IAS at lower altitudes.[39][87][page needed] Later models, the F.2A, F.3, F.3A, F.6, and F.53, had a maximum speed of Mach 2.0 (2,136 km/h; 1,327 mph) at 36,000 feet (11,000 m), and speeds up to 700 knots (1,300 km/h; 810 mph) indicated air speed for "operational necessity only".[40][41][43][88][page needed] A Lightning fitted with Avon 200-series engines, a ventral tank, and two Firestreak missiles had a maximum speed of Mach 1.9 (2,328 km/h; 1,446 mph) on a standard day;[89] while a Lightning powered by the Avon 300-series engines, a ventral tank and two Red Top missiles had a maximum speed of Mach 2.0.[62] Directional stability decreased as speed increased, with vertical fin failure likely if yaw was not correctly counteracted with rudder deflections.[f][g] Imposed Mach limits during missile launches ensured adequate directional stability;[h] later Lightning variants had a larger vertical fin, giving a greater stability margin at high speed.[91]

It was not known whether the fixed centre-body intake, with a design point of Mach 1.7, would encounter intake buzz, a vibration caused by oscillation of the shock positions at different combinations of Mach number and engine air flow/rpm.[92] A Lightning prototype was taken to Mach 2.0 (2,450 km/h; 1,522 mph) to check for this instability but none was found.[93] Service trials with the F.6 found intake buzz when engine speed was rapidly reduced at speeds above Mach 1.85 (2,266 km/h; 1,408 mph) as well as when manoeuvring (increased 'g') at other supersonic speeds and engine thrust settings. The buzz caused no damage.[94]

Thermal and structural limits were also present. Air is heated considerably when compressed by the passage of an aircraft at supersonic speeds. The airframe absorbs heat from the surrounding air, the inlet shock cone at the front of the aircraft becoming the hottest part. The shock cone was fibreglass, necessary because the shock cone also served as a radar radome; a metal shock cone would have blocked the AI 23's radar emissions. The shock cone was eventually weakened due to the fatigue caused by the thermal cycles involved in regularly performing high-speed flights. At 36,000 feet (11,000 m) and Mach 1.7 (1,815 km/h; 1,128 mph), the heating conditions on the shock cone were similar to those at sea level and 650 knots (1,200 km/h; 750 mph) indicated airspeed,[i] but if the speed was increased to Mach 2.0 (2,136 km/h; 1,327 mph) at 36,000 feet (11,000 m), the shock cone was exposed to higher temperatures[j] than those at Mach 1.7. The shock cone was strengthened on the later Lightning F.2A, F.3, F.6, and F.53 models, thus allowing routine operation at up to Mach 2.0.[95]

The small-fin variants could exceed Mach 1.7,[k] but the stability limits and shock cone thermal and strength limits made such speeds risky. The large-fin variants, especially those equipped with Avon 300-series engines could safely reach Mach 2 and, given the right atmospheric conditions, might even achieve a few more tenths of a Mach. All Lightning variants had the excess thrust to slightly exceed 700 knots (1,300 km/h; 810 mph) indicated airspeed under certain conditions,[62][89][97][page needed] and the service limit of 650 knots (1,200 km/h; 750 mph) was occasionally ignored. With the strengthened shock cone, the Lightning could safely approach its thrust limit, but fuel consumption at very high airspeeds was excessive and became a major limiting factor.[l]

Handling characteristics

[edit]The Lightning was fully aerobatic.[98]

Operational history

[edit]Royal Air Force

[edit]

The first aircraft to enter service with the RAF, three pre-production P.1Bs, arrived at RAF Coltishall in Norfolk on 23 December 1959, joining the Air Fighting Development Squadron (AFDS) of the Central Fighter Establishment, where they were used to clear the Lightning for entry into service.[99][100] The production Lightning F.1 entered service with the AFDS in May 1960, allowing the unit to take part in the air defence exercise "Yeoman" later that month. The Lightning F.1 entered frontline squadron service with 74 Squadron under the command of Squadron Leader John "Johnny" Howe at Coltishall from 11 July 1960.[2] This made the Lightning the second Western European-built combat aircraft with true supersonic capability to enter service and the second fully supersonic aircraft to be deployed in Western Europe, the first one in both categories being the Swedish Saab 35 Draken on 8 March 1960 four months earlier.[101]

The aircraft's radar and missiles proved to be effective and pilots reported that the Lightning was easy to fly. However, in the first few months of operation the aircraft's serviceability was extremely poor. This was due to the complexity of the aircraft systems and shortages of spares and ground support equipment. Even when the Lightning was not grounded by technical faults, the RAF initially struggled to get more than 20 flying hours per aircraft per month compared with the 40 flying hours that English Electric believed could be achieved with proper support.[99][102] In spite of these concerns, within six months of the Lightning entering service, 74 Squadron was able to achieve 100 flying hours per aircraft.[103]

In addition to its training and operational roles, 74 Squadron was appointed as the official Fighter Command aerobatic team for 1961, flying at air shows throughout the United Kingdom and Europe.[104] Deliveries of the slightly improved Lightning F.1A, with improved avionics and provision for an air-to-air refuelling probe, allowed two more squadrons, 56 and 111 Squadron, both based at RAF Wattisham in Suffolk to convert to the Lightning in 1960–1961.[99] The Lightning F.1 would only be ordered in limited numbers and serve for a short time; nonetheless, it was viewed as a significant step forward in Britain's air defence capabilities. Following their replacement from frontline duties by the introduction of successively improved variants of the Lightning, the remaining F.1 aircraft were employed by the Lightning Conversion Squadron.[105]

An improved variant, the F.2 first flew on 11 July 1961[106] and entered service with 19 Squadron at the end of 1962 and 92 Squadron in early 1963. Conversion of these two squadrons was aided by the use of the two seat T.4 trainer, which entered service with the Lightning Conversion Squadron (later renamed 226 Operational Conversion Unit) in June 1962. While the OCU was the major user of the two-seater, small numbers were also allocated to the front-line fighter squadrons.[107] More F.2s were produced than there were available squadron slots so later production aircraft were stored for years before being used operationally; some Lightning F.2s were converted to F.2a's. They had some of the improvements added to the F.6.[108]

The F.3, with more powerful engines and the new Red Top missile (but no cannon) was expected to be the definitive Lightning, and at one time it was planned to equip ten squadrons, with the remaining two squadrons retaining the F.2.[109] On 16 June 1962, the F.3 flew for the first time.[110] It had a short operational life and was withdrawn from service early due to defence cutbacks and the introduction of the F.6, some of which were converted F.3s.[111]

The Lightning F.6 was a more capable and longer-range version of the F.3. It initially had no cannon, but installable gun packs were made available later.[112] A few F.3s were upgraded to F.6s. Author Kev Darling suggests that decreasing British overseas defence commitments had led to those aircraft instead being prematurely withdrawn.[111] The introduction of the F.3 and F.6 allowed the RAF to progressively reequip squadrons operating aircraft such as the Gloster Javelin and retire these types during the mid-1960s.[113]

Suddenly the telephone would ring and it would be one of the radar controllers from around the UK ordering you to scramble immediately. And so you would run to the aeroplane, jump in. They [Soviet aircraft] were just monitoring, listening, recording everything that went on. So you would get up alongside and normally they would wave, quite often there would be a little white face at every window. They knew we were there just to watch them. One I intercepted when he violated the airspace and I was trying to get him to land but it was scary. He just wanted to get out of there, he was out of Dodge as fast as he could go, he didn't want to mix it with me.

—RAF Lightning pilot John Ward[114]

A Lightning was tasked with shooting down a pilot-less Hawker Siddley Harrier over West Germany in 1972. The pilot had abandoned the Harrier which continued flying toward the East German border; it was shot down to avoid a diplomatic incident.[115] During British Airways trials in April 1985, Concorde was offered as a target to NATO fighters including F-15 Eagles, F-16 Fighting Falcons, Grumman F-14 Tomcats, Dassault Mirages, and F-104 Starfighters – but only Lightning XR749, flown by Mike Hale and described by him as "a very hot ship, even for a Lightning", managed to overtake Concorde on a stern conversion intercept.[84]

During the 1960s, as strategic awareness increased and a multitude of alternative fighter designs were developed by Warsaw Pact and NATO members, the Lightning's range and firepower shortcomings became increasingly apparent. The transfer of McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom IIs from Royal Navy service enabled these much longer-ranged aircraft to be added to the RAF's interceptor force alongside those withdrawn from Germany as they were replaced by SEPECAT Jaguars in the ground attack role.[116] The Lightning's direct replacement was the Panavia Tornado F3, an interceptor variant of the Panavia Tornado multi-role aircraft. The Tornado featured several advantages over the Lightning, including a far larger weapons load and considerably more advanced avionics.[117] Lightnings were slowly phased out of service between 1974 and 1988. In their final years the airframes required considerable maintenance to keep them airworthy due to the sheer number of accumulated flight hours.[citation needed] The last flight by RAF Lightnings was on 30 June 1988 with 2 aircraft flying to Cranfield Airport from RAF Binbrook.[3]

Fighter Command and Strike Command

[edit]The main Lightning role was the air defence of the United Kingdom and was operated at first as part of Fighter Command and then from 1968 with No. 11 Group of Strike Command. At the formation of Strike Command nine Lightning squadrons were operational in the United Kingdom.[118]

Far East Air Force

[edit]In 1967 No. 74 Squadron was moved to RAF Tengah, Singapore to take over the air defence role from the Gloster Javelin equipped 60 Squadron.[119] The squadron was disbanded in 1971 following the withdrawal of British forces from Singapore.

Near East Air Force

[edit]The Royal Air Force had detached Lightnings to RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus to support the Near East Air Force and in 1967 No. 56 Squadron RAF moved from RAF Wattisham with the Lightning F.3 to provide a permanent air defence force, it converted to the F.6 in 1971 and returned to the United Kingdom in 1975.

Royal Air Force Germany

[edit]In the early 1960s No. 19 Squadron and No. 92 Squadron with Lightning F.2s, moved from RAF Leconfield to RAF Gütersloh in West Germany as part of Royal Air Force Germany and operated in the low-level air defence role until disbanded in 1977 when the role was taken over by the Phantom FGR2.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait

[edit]

On 21 December 1965, Saudi Arabia, keen to improve its air defences owing to the Saudi involvement in the North Yemen Civil War and the resultant air incursions into Saudi airspace by Egyptian forces supporting the Yemeni Republicans, placed a series of orders with Britain and the US to build a new integrated air defence system. BAC received orders for 34 multirole single-seat Lightning F.53s that could still retain very high performance and reasonable endurance, and six two-seat T.55 trainers, together with 25 BAC Strikemaster trainers, while the contract also included new radar systems, American Hawk surface-to-air missiles and training and support services.[50][120]

To provide an urgent counter to air incursions, with Saudi towns near the border being bombed by Egyptian aircraft, an additional interim contract, called "Magic Carpet", was placed in March 1966 for the supply of six ex-RAF Lightnings (four F.2s and two T.4 trainers, redesignated F.52 and T.54 respectively[m]), six Hawker Hunters, two air defence radars and a number of Thunderbird surface-to-air missiles.[50][120] The "Magic Carpet" Lightnings were delivered to Saudi Arabia in July 1966. One lost in an accident was later replaced in May 1967. The Lightnings and Hunters, flown by mercenary pilots, were deployed to Khamis Mushait airfield near the Yemeni border, resulting in the curtailing of operations by the Egyptian Air Force over the Yemeni-Saudi border.[46][120] During the Al-Wadiah War, RSAF Lightnings flown by Saudi and Pakistan Air Force pilots participated in the airstrikes on Yemeni militias after they captured a town in Saudi Arabia in 1969.

Kuwait ordered 14 Lightnings in December 1966; 12 F.53Ks and two T.55Ks. The first Kuwait aircraft, a T.55K first flew on 24 May 1968 and deliveries to Kuwait started in December 1968.[122] The Kuwaitis somewhat overestimated their ability to maintain such a complex aircraft, not adopting the extensive support from BAC and Airwork Services that the Saudis used to keep their Lightnings operational, so serviceability was poor.[123]

Saudi Arabia officially received F.53 Lightnings in December 1967, although they were kept at Warton while trials and development continued and the first Saudi Lightnings to leave Warton were four T.55s delivered in early 1968 to the Royal Air Force 226 Operational Conversion Unit at RAF Coltishall, the four T.55s were used to train Saudi aircrew for the next 18 months.[124] The new-build Lightnings were delivered under Operation "Magic Palm" between July 1968 and August 1969. Two Lightnings, a F.53 and a T.55 were destroyed in accidents prior to delivery, and were replaced by two additional aircraft, the last of which was delivered in June 1972.[121][125] The multirole F.53s served in the ground-attack and reconnaissance roles as well as an air defence fighter, with Lightnings of No 6 Squadron RSAF carrying out ground-attack missions using rockets and bombs during a border dispute with South Yemen between December 1969 and May 1970. One F.53 (53–697) was shot down by Yemeni ground fire on 3 May 1970 during a reconnaissance mission, with the pilot ejecting successfully and being rescued by Saudi forces.[125][126] Saudi Arabia received Northrop F-5E fighters from 1971, which resulted in the Lightnings relinquishing the ground-attack mission, concentrating on air defence, and to a lesser extent, reconnaissance.[127]

Kuwait's Lightnings did not have a long service career. After an unsuccessful attempt by the regime to sell them to Egypt in 1973, the last Lightnings were replaced by Dassault Mirage F1s in 1977.[128] The remaining aircraft were stored at Kuwait International Airport, and many were destroyed during the Invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in August 1990.[129]

Until 1982, Saudi Arabia's Lightnings were mainly operated by 2 and 6 Squadron RSAF (although a few were also used by 13 Squadron RSAF), but when 6 Squadron re-equipped with the F-15 Eagle all the remaining aircraft were operated by 2 Squadron at Tabuk.[130][131] In 1985 as part of the agreement to sell the Panavia Tornado to the RSAF, the 22 flyable Lightnings were traded in to British Aerospace and returned to Warton in January 1986.[130] While BAe offered the ex-Saudi Lightnings to Austria and Nigeria, no sales were made, and the aircraft were eventually disposed of to museums.[125][132]

Variants

[edit]

- English Electric P.1A

- Single-seat supersonic research aircraft, two prototypes built and one static test airframe.

- English Electric P.1B

- Single-seat operational prototypes to meet Specification F23/49, three prototypes built, further 20 development aircraft ordered in February 1954. Type was officially named 'Lightning' in October 1958.

- Lightning F.1

- Development batch aircraft, single-seat fighters delivered from 1959, a total of 19 built (and one static test airframe). Nose-mounted twin 30 mm ADEN cannon, two Firestreak missiles, VHF Radio and Ferranti AI-23 "AIRPASS" radar.

- Lightning F.1A

- Single-seat fighter, delivered in 1961. Featured Avon 210R engines, an inflight refuelling probe and UHF Radio; a total of 28 built.

- Lightning F.2

- Single-seat fighter (an improved variant of the F.1), delivered in 1962. A total of 44 built with 31 later modified to F.2A standard, five later modified to F.52 for export to Saudi Arabia.

- Lightning F.2A

- Single-seat fighter (F.2s upgraded to near F.6 standard); featuring Avon 211R engines, retained ADEN cannon and Firestreak (replaceable Firestreak pack swappable with ADEN Cannon Pack for a total of four ADEN Cannon), arrestor hook and enlarged Ventral Tank for two hours flight endurance. A total of 31 converted from F.2.

- Lightning F.3

- Single-seat fighter with upgraded AI-23B radar, Avon 301R engines, new Red Top missiles, enlarged and clipped tailfin due to aerodynamics of carriage of Red Top, and deletion of ADEN cannon. A total of 70 built (at least nine were converted to F.6 standard).

- Lightning F.3A

- Single-seat fighter with extended range of 800 miles due to large ventral tank and new cambered wings. A total of 16 built, known also as an F.3 Interim version or F.6 Interim Version, 15 later modified to F.6 standard.

- Lightning T.4

- Two-seat side-by-side training version, based on the F.1A; two prototypes and 20 production built, two aircraft later converted to T.5 prototypes, two aircraft later converted to T.54.

- Lightning T.5

- Two-seat side-by-side training version, based on the F.3; 22 production aircraft built. One former RAF aircraft later converted to T.55 for Saudi Arabia.

- Lightning F.6

- Single-seat fighter (an improved longer-range variant of the F.3). It featured new wings with better efficiency and subsonic performance, overwing fuel tanks and a larger ventral fuel tank, reintroduction of 30 mm cannon (initially no cannon but later in the forward part of the ventral pack rather than in the nose), use of Red Top missiles. A total of 39 built (also nine converted from F.3 and 15 from F.3A).

- Lightning F.7

- Proposed single-seat interceptor featuring variable geometry wings, extended fuselage, relocated undercarriage, underwing hardpoints, cheek-mounted intakes, new radar, and use of the Sparrow and Skyflash AAMs. Never built.[133]

- Lightning F.52

- Slightly modified ex-RAF F.2 single-seat fighters for export to Saudi Arabia (five converted).

- Lightning F.53

- Export version of the F.6 with pylons for bombs or unguided rocket pods, 44 × 2 in (50 mm), total of 46 built and one converted from F.6 (12 F.53Ks for the Kuwaiti Air Force, 34 F.53s for the Royal Saudi Arabian Air Force, one aircraft crashed before delivery).

- Lightning T.54

- Ex-RAF T.4 two-seat trainers supplied to Saudi Arabia (two converted).

- Lightning T.55

- Two-seat side-by-side training aircraft (export version of the T.5), eight built (six T.55s for the Royal Saudi Arabian Air Force, two T.55Ks for the Kuwaiti Air Force and one converted from T.5 that crashed before delivery).

- Sea Lightning FAW.1

- Proposed two-seat Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm carrier capable variant with variable-geometry wing; not built.[53]

Operators

[edit]Military operators

[edit]- Kuwait Air Force operated both the F.53K (12) single-seat fighter and the T.55K (2) training version from 1968 to 1977.

- Royal Saudi Air Force operated the Lightning from 1967 to 1986.

- 2 Squadron operated the F.53 and T.55

- 6 Squadron operated the F.52 and F.53

- 13 Squadron operated the F.52, F.53 and T.55

- RSAF Lightning Conversion Unit

- Royal Air Force operated the Lightning from 1959 to 1988.

- RAF Aerial display teams

-

- 'The Tigers' of No 74 Squadron. Lead RAF aerial display team from 1962 and first display team with Mach 2 aircraft.

- 'The Firebirds' of No 56 Squadron from 1963 in red and silver.

- RAF Squadrons

-

- 5 Squadron formed at RAF Binbrook on 8 October 1965, operating the Lightning F.6 and T.5. A few F.1s, F.1As and F.3s were used as targets (and later for air display use) from 1971. The Squadron remained operational at Binbrook with the Lightning F.6 until 1987, disbanding on 31 December.[134]

- 11 Squadron formed at RAF Leuchars in April 1967 with the Lightning F.6. It moved to RAF Binbrook in March 1972, receiving a few F.3s for target duties. It remained operational until 1988, disbanding on 30 April 1988.[134]

- 19 Squadron operated the F.2 and the F.2A (1962–1976)

- 23 Squadron operated the F.3 and the F.6 (1964–1975)

- 29 Squadron operated the F.3 (1967–1974)

- 56 Squadron operated the F.1, F.1A, F.3 and the F.6 (1960–1976)

- 65 Squadron operated as No. 226 OCU with the F.1, F.1A and the F.3 (1971–1974)

- 74 Squadron operated the F.1, F.3 and the F.6 (1960–1971)

- 92 Squadron operated the F.2 and the F.2A (1963–1977)

- 111 Squadron operated the F.1A, F.3 and the F.6 (1961–1974)

- 145 Squadron operated as No. 226 OCU with the F.1, F.1A and the F.3 (1963–1971)

- 226 Operational Conversion Unit operated the F.1A, F.3, T.4 and the T.5 (1963–1974)

- Air Fighting Development Squadron

- Lightning Conversion Squadron (1960–1963)

- RAF Flights

-

- Binbrook Target Facilities Flight (1966–1973)

- Leuchars Target Facilities Flight (1966–1973)

- Wattisham Target Facilities Flight (1966–1973)

- Lightning Training Flight (1975–1987)

- RAF Stations

Civil operators

[edit]

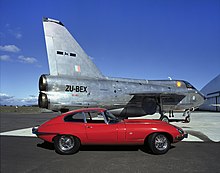

Thunder City, a private company based at Cape Town International Airport, South Africa operated one Lightning T.5 and two single-seat F.6es. The T.5 XS452, (civil registration ZU-BBD) flew again on 14 January 2014 after restoration and is currently the only airworthy example.[135] A Lightning T.5, XS451 (civil registration ZU-BEX) belonging to Thunder City crashed after developing mechanical problems during its display at the biennial South African Air Force Overberg Airshow held at AFB Overberg near Bredasdorp on 14 November 2009.[136] The Silver Falcons, the South African Air Force's official aerobatic team, flew a missing man formation after it was announced that the pilot had died in the crash.[137]

- British Aerospace operated four ex-RAF F.6s as radar targets to aid development of the Panavia Tornado ADV's AI.24 Foxhunter radar from 1988 to 1992.[138][139]

- The Anglo-American Lightning Organisation, a group based at Stennis Airport, Kiln, Mississippi, is returning EE Lightning T.5, XS422 to airworthy status. As of March 2021, the aircraft was capable of fast taxiing down a runway. The aircraft was formerly with the Empire Test Pilots' School (ETPS) at Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, UK.[140]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]A complete list is available here.

Cyprus

[edit]- On display

-

- XS929 Lightning F.6 at RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus.[141]

France

[edit]- On display

-

- XM178 Lightning F.1A at Savigny-les-Beaune.[142]

Germany

[edit]- On display

-

- XN782 Lightning F.2A at the Flugausstellung Hermeskeil, Germany.[143]

- XN730 Lightning F.2A at the Militärhistorisches Museum Flugplatz Berlin-Gatow, Germany.[144]

Kuwait

[edit]- On display

- 53–418 Lightning F.53 at the Kuwait Science and Natural History Museum, Kuwait City. It can be seen from surrounding buildings and is located at 29°22′14″N 47°58′36″E / 29.370648°N 47.976615°E.

- Lightning F.53 at the Abdullah Al-Mubarak Air Base.[citation needed]

- Three Lightnings on stands at Al Jaber Air Base[citation needed]

Netherlands

[edit]- On display

-

- XN784 Lightning F.2A owned by PS Aero in Holland, on display at their facility in Baarlo.[145]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]- On display

- XN770 Lightning F.52 at the Royal Saudi Air Force Museum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

- XM989 Lightning T.54 at the main entrance to King Abdul-Aziz Air Base, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

- 55–716 Lightning T.55 at the Royal Saudi Air Force Museum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

- "227" Lightning Mark F.53 pylon-mounted on static display in a traffic circle outside the main gate of King Faisal Air Base in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. GPS 28.387229, 36.594182

- "486" Lightning pylon-mounted on static display in a traffic circle outside the main gate of Prince Sultan Air Base in Al Kharj, Saudi Arabia. GPS 24.175664, 47.517913

The following are on display but with no public access:

- XG313 Lightning F.1 at the VIP terminal on King Abdulaziz Air Base Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

- XN767 Lightning F.52 pylon mounted at the Aeromedical centre on King Abdulaziz Air Base Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

- Unidentified Lightning at entrance to Taif Heart Mall in downtown Taif, Saudi Arabia.

- "224" Lightning Mark F.53 on display at Royal Saudi Air Force, King Khalid Airbase in Khamis Mushyt, Saudi Arabia. GPS 18.260764, 42.795216

- Unidentified Lightning mounted in a static display on the Royal Saudi Air Force, King Khalid Airbase in Khamis Mushyt, Saudi Arabia. GPS 18.272086, 42.805935

- Unidentified Lightning on display in a small air park just inside the main gate of King Faisal Air Base in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. GPS 28.380036, 36.605270

South Africa

[edit]- Stored or under restoration

- ZU-BBD (former XS452) Lightning T.5 based at Cape Town under restoration to fly.[citation needed]

- ZU-BEW (former XR773) Lightning F.6 stored in Cape Town under restoration to fly.[citation needed]

- ZU-BEY (former XP693) Lightning F.6 stored in Cape Town under restoration to fly.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

[edit]- On display

-

- WG760, the first prototype P.1A at the RAF Museum Cosford, England[146]

- WG763, the second prototype P.1A at the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, England[147]

- XG329 P1B/Lightning F.1 pre-production aircraft at the Norfolk & Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton, England[148]

- XG337 P1B/Lightning F.1 pre-production aircraft at the RAF Museum Cosford[149]

- XM135 Lightning F.1 at the Imperial War Museum Duxford – flown by non-pilot Walter Holden[150]

- XM173 Lightning F.1A at Dyson Ltd. (on display in staff canteen), Malmesbury, Wiltshire.

- XM192 Lightning F.1A at Tattershall Thorpe, Lincolnshire, England[151]

- XN726 Lightning F.2A cockpit section at the Boscombe Down Aviation Collection, Old Sarum Airfield, Wiltshire[4]

- XN776 Lightning F.2A at the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune, Scotland[152]

- XP706 Lightning F.3 at South Yorkshire Aircraft Museum, Doncaster, England[153]

- XP745 Lightning F.3 at Vanguard Self Storage, Bristol, England[154]

- XR713 Lightning F.3 owned by Lightning Preservation Group, Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome, Leicestershire

- XR718 Lightning F.3 owned by Anthony Harker, Over Dinsdale, Darlington, Durham.

- XR749 Lightning F.3 outside Score Group's Integrated Valve and Gas Turbine Plant, Peterhead, Scotland[155]

- XS417 Lightning T.5 at the Newark Air Museum, Newark, England[156]

- XS420 Lightning T.5 on loan to the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, Farnborough, England[157]

- XS456 Lightning T.5 at the Skegness Water Leisure Park, Lincolnshire[158]

- XS458 Lightning T.5 is in taxiable condition at Cranfield Airport, Bedfordshire, England[159]

- XS459 Lightning T.5 at the Fenland and West Norfolk Aviation Museum, Wisbech, England[160]

- XR753 Lightning F.6 at RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire[161]

- XR755 Lightning F.6 near Callington, Cornwall.

- XR728 Lightning F.6 with LPG, in taxiable condition at Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome, Leicestershire, England[162]

- XR770 Lightning F.6 at RAF Manston Museum, Kent, England[163]

- XR771 Lightning F.6 at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England[164]

- XS897 Lightning F.6 (painted as F.3 XP765) at RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire[161]

- XS903 Lightning F.6 at the Yorkshire Air Museum, Elvington, England[165]

- XS904 Lightning F.6 with LPG, in taxiable condition at Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome, Leicestershire, England[162]

- XS919 Lightning F.6 at Henstridge Airfield, Somerset, England

- XS925 Lightning F.6 stand mounted at Castle Motors on the A38 near Liskeard, Cornwall, England[166]

- XS928 Lightning F.6 at Warton Aerodrome, Lancashire[167]

- XS936 Lightning F.6 at the Royal Air Force Museum London, England[168]

- ZF578 Lightning F.53 as XR753 at the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, Tangmere, England[169]

- ZF579 Lightning F.53 in taxiable condition at Gatwick Aviation Museum, Charlwood, near Gatwick Airport, England[170]

- ZF580/XR768 Lightning F.53 at Cornwall Aviation Heritage Centre, Newquay Airport, Cornwall, England.[171]

- ZF583 Lightning F.53 at the Solway Aviation Museum, Carlisle Airport Cumbria England[172]

- ZF584 Lightning F.53 at the Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum, Dumfries, Scotland[173]

- ZF588 Lightning F.53 at the East Midlands Aeropark, Castle Donington, Derbyshire

- ZF592 Lightning F.53 as 53–686 at the City of Norwich Aviation Museum, Norwich, England[174]

- ZF594 Lightning F.53 painted as XS933 at the North East Aircraft Museum, Sunderland, England[175]

- ZF598 Lightning T.55 as 55–713 at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England[164]

- XL629 Lightning T.4 inside the main gate at MoD Boscombe Down, Wiltshire, England[176]

- Stored or under restoration

-

- XM172 Lightning F.1A in a private collection at Spark Bridge, Cumbria[177]

- XS416 Lightning T.5 in a private collection at New York, Lincolnshire[178]

- XR724 Lightning F.6 is in taxiable condition at the former RAF Binbrook, Lincolnshire[179]

- XR725 Lightning F.6 in a private collection at Binbrook, Lincolnshire[180]

- ZF581 Lightning F.53 Under restoration at the Bentwaters Cold War Museum, Suffolk, England[181]

United States

[edit]- On display

- ZF593 Lightning F.53 painted in 5 Squadron camouflage colours, on display at Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.

- ZF597 Lightning T.55 painted in RAF markings, on display at Olympic Flight Museum in Olympia, Washington. Around 2009/2010, the aircraft had moved from the Olympic Flight Museum, possibly to Stennis, Mississippi, where it was stripped for parts to help get XS422 back in the air. Not much of ZF597 was seen until the cockpit appeared on eBay in May 2019. It is unknown as to where the nose section is now and what the future holds for it.[182]

- Stored or under restoration

- XS422 Lightning T.5 painted in RAF markings, under restoration to fly at Stennis International Airport, in Hancock County, Mississippi. (owned by the Anglo-American Lightning Organisation who also own the cockpit of ZF595 which is being used as a parts donor for XS422).

Specifications (Lightning F.6)

[edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

Data from Pilots Notes and Operating Data Manual for Lightning F.6 (unless otherwise noted)[41][verification needed][62]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 55 ft 3 in (16.84 m) [183]

- Wingspan: 34 ft 10 in (10.62 m) [51]

- Height: 19 ft 7 in (5.97 m) [51]

- Wing area: 474.5 sq ft (44.08 m2) [184]

- Empty weight: 31,068 lb (14,092 kg) with armament and no fuel[62][n]

- Gross weight: 41,076 lb (18,632 kg) with two Red Top missiles, cannon, ammunition, and internal fuel[62]

- Max takeoff weight: 45,750 lb (20,752 kg) [41][o][185] [verification needed]

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Avon 301R afterburning turbojet engines, 12,690 lbf (56.4 kN) thrust each dry, 16,360 lbf (72.8 kN) with afterburner

Performance[p]

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.27 (1,500 mph+ at 40,000 ft)[citation needed]

- Range: 738 nmi (849 mi, 1,367 km) [62][q]

- Combat range: 135 nmi (155 mi, 250 km) supersonic intercept radius[62][r]

- Ferry range: 800 nmi (920 mi, 1,500 km) internal fuel; 1,100 nmi (1,300 mi; 2,000 km) with external tanks[62]

- Service ceiling: 60,000 ft (18,000 m) [62]

- Zoom ceiling: 70,000 ft (21,000 m)[62][187]

- Rate of climb: 20,000 ft/min (100 m/s) sustained to 30,000 ft (9,100 m)[62][s] Zoom climb 50,000 ft/min[188]

- Time to altitude: 2.8 min to 36,000 ft (11,000 m)[62][t]

- Wing loading: 76 lb/sq ft (370 kg/m2) F.6 with Red Top missiles and 1/2 fuel[u]

- Thrust/weight: 0.78 (1.03 empty)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm (1.181 in) ADEN cannon

- Hardpoints: 2 × forward fuselage, 2 × overwing pylon stations , with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: 2× de Havilland Firestreak or 2 × Red Top (missile) on fuselage

- Other: 260 imp gal (310 US gal; 1,200 L) ferry tanks on wings

Notable appearances

[edit]- The 1965 period comedy film Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines set in 1910 ends with a flyover of six English Electric Lightnings.

- British journalist and TV presenter Jeremy Clarkson borrowed a Lightning (serial XM172) which was temporarily placed in his garden and documented on Clarkson's 2001 television series Speed.[189]

- In a 2010 episode of the BBC TV programme Wonders of the Solar System, Professor Brian Cox had a Lightning (XS451) with civil registration in South Africa climb to a very high altitude, allowing Cox to show the curvature of the Earth and the relative dimensions of the atmosphere.[190] This aircraft crashed in November 2009, a month after the episode was filmed, when it developed mechanical problems during an air show at South Africa's AFB Overberg.[136]

See also

[edit]- Holden's Lightning flight – an inadvertent Lightning flight by a non-pilot engineer

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Convair F-102 Delta Dagger – (United States)

- Convair F-106 Delta Dart – (United States)

- Dassault Mirage III – (France)

- Lockheed F-104 Starfighter – (United States)

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 – (Soviet Union)

- Saab 35 Draken – (Sweden)

- Sukhoi Su-15 – (Soviet Union)

Related lists

- List of accidents and incidents involving the English Electric Lightning

- List of aircraft of the Royal Air Force

- List of fighter aircraft

Notes

[edit]- ^ Formerly of Hawker Aircraft

- ^ Formerly of Vickers

- ^ The ventral cannon installation was designed for the export aircraft but was later adopted by the RAF for the F.6 and F.2A.[46]

- ^ The Lightning would increase forward velocity during the climb, the angle of the climb lessening from about 27 deg to 19 deg at 13,000 ft (4,000 m).[citation needed]

- ^ The true airspeed associated with a given indicated airspeed increases with altitude. Below the tropopause, the true airspeed associated with a given Mach number decreases with altitude. The Lightning's Air Data System automatically corrected for errors in position and speed. Following correction, 450 KIAS was equal to Mach 0.87 (1,009 km/h; 627 mph) at 13,000 ft (4,000 m).[62]

- ^ Along with directional stability, rudder effectiveness decreased at higher Mach numbers; timely and larger deflections of the rudder were required to counter any yaw, especially under increased g-loading.[39][41]

- ^ Two Lightning prototypes, XL628 and XM966, were lost to vertical fin failure during roll testing at high Mach numbers.[90]

- ^ Firestreak firing limits were Mach 1.3 (1,593 km/h; 990 mph) with the small fin, Mach 1.7 (2,083 km/h; 1,294 mph) with the large fin. Red Top limit was Mach 1.8.[39][41]

- ^ On a standard day, the temperature of the air at the tip of the shock cone (stagnation temperature) was 156 °F (69 °C) at Mach 1.7 (1,815 km/h; 1,128 mph) and 36,000 feet (11,000 m). At sea level and 650 knots (1,200 km/h; 750 mph) indicated airspeed, this temperature was 151 °F (66 °C).

- ^ At Mach 2.0, the stagnation temperature was 242 °F (117 °C)

- ^ Roland Beamont took the Lightning P.1B XA847, a prototype of the F.1, to Mach 2.0. Prior testing had determined that the aircraft had the excess thrust to achieve this speed, given the right atmospheric conditions. The test flight was to check for inlet stability and monitor temperatures at higher Mach. The aircraft was equipped with a temperature probe to monitor the stagnation temperature, up to a never-exceed temperature of 115 °C. On 28 November 1958, with a high tropopause and low −67 °C at 40,000 feet (12,000 m), Beamont achieved Mach 2.0 (2,125 km/h; 1,320 mph) in a British aircraft for the first time. This was reached only 7 minutes after takeoff, but the record dash left the Lightning critically short of fuel.[96] The Machmeter fitted to service Lightning F.1s and F.1Bs had a scale that stopped at Mach 1.8 (2,205 km/h; 1,370 mph) – with a redline at 1.7.[39]

- ^ At 30,000 feet (9,100 m), a Lightning F.6 required approximately 1 minute and 1,250 pounds (570 kg) of fuel to accelerate from 650 to 675 knots (1,204 to 1,250 km/h; 748 to 777 mph) indicated airspeed.[62][page needed]

- ^ A single F.1 was supplied as a ground instructional airframe.[121]

- ^ The value for "empty weight" is zero fuel weight, which includes equipped pilot, Red Top missiles, cannon and ammunition. The weight without these items is 27,759 lb.[62][page needed]

- ^ Above 45,000 lb, the mainwheel tyres were single use.[41]

- ^ An F.6 equipped with Red Top missiles can reach Mach 2.0 (2,450 km/h; 1,522 mph) on an ICAO standard day at 36,000 ft. True performance was not in pilot notes due to sensitivity during the Cold War. The F.6 is noted to reach Mach 2.27 (2,781 km/h; 1,728 mph) at 40,000 ft [186][verification needed]

- ^ This is based on a maximum-range subsonic intercept radius of 370 nmi (430 mi; 690 km). An F.6 equipped with Red Top missiles can climb to 36,000 ft and cruise at Mach 0.87 (1,066 km/h; 662 mph) to a loiter or intercept area 370 nmi (690 km) distant. It then has 15 minutes on station to complete the intercept or identification task before returning to base. The afterburners are not used during this profile, and the total mission time is 112 min.[62]

- ^ An F.6 equipped with Red Top missiles can climb to 36,000 ft, accelerate to Mach 1.8, and intercept a target at 135 nmi (250 km) only 10.7 min after brake release. A 2g level turn allows a second attack from the rear-quarter 1.6 min later. Following a best-range cruise and descent, the Lightning can enter the landing pattern with 800 lb of fuel remaining with a total mission time of 35 min.[62]

- ^ From Part 3, Page 11 in Operating Data Manual; at standard atmosphere, full fuel, and 2 Red Top missiles, from sea level, 450 kn (830 km/h; 520 mph) IAS -> M0.87 climb profile. When clean, this climb rate increases to 22,000 ft/min (110 m/s)

- ^ From brake release. Identical page, configuration, and profile as loaded sustained climb rate above. Time following initial acceleration (0.7 min) to climb speed is 2.1 min. When clean, these times shorten to 2.7 min from brake release, or 2.0 min after acceleration[citation needed]

- ^ Wing loading can range from 86–67 lb/sq ft (420–330 kg/m2) over the duration of a mission, depending on fuel load.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Winchester 2006, p. 82.

- ^ a b Lake 1997, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c March 1989, p. 88.

- ^ a b Note: at the time, the V bombers carried Britain's nuclear deterrent and thus were the likely first-strike targets of a Soviet air attack on the UK. In addition to the Lightning, the last line of defence for the airfields was to be what became the Bristol Bloodhound guided missile.

- ^ Note: the original specification called for a 150-mile radius of action from the V bomber bases the aircraft was defending. Roland Beamont later called for the Lightning's fuel capacity to be greatly increased, which it was.

- ^ Williamson, Ian (2020). Lightning, The Glory Days. Oxford: ADW Publications. p. 6.

- ^ Robinson, Ben. "Historic jet plane gets engineering 'wings' at Lancashire" Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Lancashire Evening Post, Retrieved: 23 January 2010.

- ^ Halpenny 1984, [page needed]

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Davies (2014), p. 104.

- ^ Davies (2014), p. 102.

- ^ a b "English Electric Lightning". www.baesystems.com. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b Davies (2014), p. 103.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Phil Butler. "Post-1950 Aircraft Specifications". Air-Britain Aeromilitaria. Vol. 37, no. 145. Air-Britain. pp. 24–25. ISSN 0262-8791.

- ^ Gunston, Bill (1976). Early Supersonic Fighters Of The West. Allan. p. 18. ISBN 0-7110-0636-9.

- ^ Longworth, James H. (2005). Triplane to Typhoon. Preston, UK: Lancashire County Developments Ltd. p. 318. ISBN 1-8-999-07-971.

- ^ English Electric Lightning, Bryan Philpott1984, ISBN 0 85059 687 4, p. 160

- ^ Darling 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Scott 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Beamont (1985), pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Buttler 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Beamont 1985 p.123

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 10–12.

- ^ a b "Progress with the P.1" Flight, 26 April 1957, p. 543.

- ^ Buttler 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Gibson & Buttler 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Aylen 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Beamont (1985), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Beamont (1985), p. 59.

- ^ Slayton D.K. with Cassutt M. (1995). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. Forge Books. ISBN 978-0-3128-5918-3.

- ^ a b c d "Champagne for the Mach 2 fighter". Flight. 31 October 1958. p. 693. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Bowman, Martin W. (30 January 2018). Images of war. The English Electric Lightning. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781526705587.

- ^ Beamont (1985), p. 67.

- ^ Dildy, Douglas C; Calcaterra, Pablo (21 September 2017). Sea Harrier FRS 1 vs Mirage III/Dagger: South Atlantic 1982. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781472818904.

- ^ Scott 2000, pp. 119–129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pilot's Notes, Lightning F Mk.1 and F Mk.1A. Warton Aerodrome, UK: English Electric Technical Services, February 1962.

- ^ a b Pilot's Notes, Lightning F.Mk.3. Warton Aerodrome, UK: English Electric Technical Services, April 1965.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pilot's Notes, Lightning F.Mk.6. Warton Aerodrome, UK: English Electric Technical Services, September 1966.

- ^ Williams and Gustin 2004, p. 106.

- ^ a b Lightning F.Mk.2A Aircrew Manual. Warton Aerodrome, UK: English Electric Technical Services, July 1968.

- ^ Flight International 5 September 1968, p. 371.

- ^ Flight International 5 September 1968, pp. 372–373.

- ^ a b Lake 1997, p. 57.

- ^ Flight International 5 September 1968, p. 373.

- ^ Gunston and Spick 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Flight International 5 September 1968, pp. 372–373, 376.

- ^ a b c Lake 1997, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c McLelland 2009, [page needed]

- ^ Wood 1986, pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b c Buttler 2005, pp. 114–117.

- ^ "Multi-mission Lightning". Flight International. 5 September 1960. p. 372. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Progress with the P.1". Flight. 26 April 1957. p. 544. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Multi-Mission Lightning". Flight International. 5 September 1968. p. 376. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Lightning Squadron". Flight. 24 February 1961. p. 231. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 32, 66.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Scott 2000, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Lightning F Mk.6 Operating Data Manual. Warton Aerodrome, UK: English Electric Technical Services, May 1977.

- ^ Scott 2000, pp. 139–142.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 45, 78.

- ^ Darling 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 35–38, 54, 78.

- ^ a b "1961 – 0950 – Flight Archive".

- ^ Darling 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 26, 27, 38.

- ^ Darling 2008, pp. 27, 35.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 20, 25, 35.

- ^ "1961 – 0949 – Flight Archive". Flight. 1961. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Darling 2000, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Darling 2008, p. 35.

- ^ a b Jackson Air International June 1986, p. 283.

- ^ Lake 1997, pp. 51–52, 71–73.

- ^ Lake 1997, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Flight International "BAC Lightning" 21 March 1968. Image caption between page 408 and 409

- ^ Public Record Office, London. TNA AIR 20/11370

- ^ "Piece details AIR 20/11370."The National Archive of United Kingdom. Retrieved: 23 January 2010.

- ^ Public Record Office, London. TNA AIR 20/11370

- ^ Black, I. "Chasing the Dragon Lady". Classic Aircraft, Volume 45, Number 8.

- ^ a b Ross, Charles. "Lightning vs Concorde" Archived 4 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Lightning Association. October 2004. Retrieved: 9 August 2020.