Catholic Church in the United States

| Catholic Church in the United States | |

|---|---|

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, in Washington, D.C., is the largest Catholic church building in North America. | |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Region | United States, Puerto Rico, and other territories of the United States |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Founder | Bishop John Carroll |

| Origin | 1789 |

| Members | 70,412,021 (as of 2017) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church by country |

|---|

|

|

|

The Catholic Church in the United States is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in communion with the Pope. With 77.4 million members, it is the largest religious denomination in the United States, comprising 22% of the population as of 2017.[1] The United States has the fourth largest Catholic population in the world, after Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines,[2] the largest Catholic minority population, and the largest English-speaking Catholic population.

Catholicism arrived in what is now the United States in the earliest days of the European colonization of the Americas. The first Catholics were Spanish missionaries who came with Christopher Columbus to the New World on his second voyage in 1493.[3] In the 16th and 17th centuries, they established missions in what are now Florida, Georgia, New Mexico, Puerto Rico, Texas and later in California.[4][5] French colonization in the early 18th century saw missions established in Louisiana, St. Louis, New Orleans, Biloxi, Mobile, the Alabamas, Natchez, Yazoo, Natchitoches, Arkansas, Illinois,[6] and Michigan. In 1789 the Archdiocese of Baltimore was the first diocese established in the United States and John Carroll, whose brother Daniel was one of five men to sign both the Articles of Confederation (1778) and the United States Constitution (1787), was the first American bishop.[7] John McCloskey was the first American cardinal in 1875.

The number of Catholics grew from the early 19th century through immigration and the acquisition of the predominantly Catholic former possessions of France, Spain, and Mexico, followed in the mid-19th century by a rapid influx of Irish, German, Italian and Polish immigrants from Europe, making the Catholic Church the largest Christian denomination in the United States. This increase was met by widespread Anti-Catholicism in the United States, prejudice and hostility, often resulting in riots and the burning of churches, convents, and seminaries.[8] The Know Nothings, an anti-Catholic nativist movement, was founded in the mid 19th century in an attempt to restrict Catholic immigration and was later followed by the Order of United American Mechanics, the Ku Klux Klan, the American Protective Association, and the Junior Order of United American Mechanics.

The integration of Catholics into American society was marked by the election of John F. Kennedy as President in 1960. Since then, the percentage of Americans who are Catholic has fallen slowly from about 25% to 22%,[9] with increases in Hispanics, especially Mexican Americans, who have balanced losses of self-identifying Catholics among other ethnic groups. As of 2017 Catholics serve as former Vice President (Joe Biden), Speaker of the House of Representatives (Paul Ryan), Chief Justice (John Roberts), Justices of the Supreme Court (six out of 9, including Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch who was raised Catholic albeit worships at an Episcopal church),[10][11] and a plurality of Senators, Representatives,[12] and Governors.

Organization

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

Catholics gather as local communities called parishes, headed by a priest, and typically meet at a permanent church building for liturgies every Sunday, weekdays and on holy days. Within the 196 geographical dioceses and archdioceses (excluding the Archdiocese for the Military Services), there are 17,651 local Catholic parishes in the United States.[14] The Catholic Church has the third highest total number of local congregations in the US behind Southern Baptists and United Methodists. However, the average Catholic parish is significantly larger than the average Baptist or Methodist congregation; there are more than four times as many Catholics as Southern Baptists and more than eight times as many Catholics as United Methodists.[15]

In the United States, there are 197 ecclesiastical jurisdictions:

- 177 Latin Catholic dioceses

- including 32 Latin Catholic archdioceses

- 18 Eastern Catholic dioceses (eparchies)

- including 2 Eastern Catholic archdioceses (archeparchies)

- including 1 apostolic exarchate (for the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church)

- 2 personal ordinariates

- one for former Anglicans who came into full Catholic communion

- one for members of the military (though equivalent to an archdiocese, it is technically a military ordinariate)

Eastern Catholic Churches are churches with origins in Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa that have their own distinctive liturgical, legal and organizational systems and are identified by the national or ethnic character of their region of origin. Each is considered fully equal to the Latin tradition within the church. In the United States, there are 15 Eastern church dioceses (called eparchies) and two Eastern church archdioceses (or archeparchies), the Byzantine Catholic Archeparchy of Pittsburgh and the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia.

The apostolic exarchate for the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church in the United States is headed by a bishop who is a member of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. An apostolic exarchate is the Eastern Catholic Church equivalent of an apostolic vicariate. It is not a full-fledged diocese/eparchy, but is established by the Holy See for the pastoral care of Eastern Catholics in an area outside the territory of the Eastern Catholic Church to which they belong. It is headed by a bishop or a priest with the title of exarch.

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter was established January 1, 2012, to serve former Anglican groups and clergy in the United States who sought to become Catholic. Similar to a diocese though national in scope, the ordinariate is based in Houston, Texas and includes parishes and communities across the United States that are fully Catholic, while retaining elements of their Anglican heritage and traditions.

As of 2017[update], 8 dioceses out of 195 are vacant (sede vacante). None of the current bishops or archbishops are past the retirement age of 75.

The central leadership body of the Catholic Church in the United States is the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, made up of the hierarchy of bishops (including archbishops) of the United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands, although each bishop is independent in his own diocese, answerable only to the Holy See. The USCCB elects a president to serve as their administrative head, but he is in no way the "head" of the Church or of Catholics in the United States. In addition to the 195 dioceses and one exarchate[16] represented in the USCCB, there are several dioceses in the nation's other four overseas dependencies. In the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the bishops in the six dioceses (one metropolitan archdiocese and five suffragan dioceses) form their own episcopal conference, the Puerto Rican Episcopal Conference (Conferencia Episcopal Puertorriqueña).[17] The bishops in US insular areas in the Pacific Ocean—the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Territory of American Samoa, and the Territory of Guam—are members of the Episcopal Conference of the Pacific.

No primate exists for Catholics in the United States. In the 1850s, the Archdiocese of Baltimore was acknowledged a Prerogative of Place, which confers to its archbishop some of the leadership responsibilities granted to primates in other countries. The Archdiocese of Baltimore was the first diocese established in the United States, in 1789, with John Carroll (1735–1815) as its first bishop. It was, for many years, the most influential diocese in the fledgling nation. Now, however, the United States has several large archdioceses and a number of cardinal-archbishops.

By far, most Catholics in the United States belong to the Latin Church and the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. Rite generally refers to the form of worship ("liturgical rite") in a church community owing to cultural and historical differences as well as differences in practice. However, the Vatican II document, Orientalium Ecclesiarum ("Of the Eastern Churches"), acknowledges that these Eastern Catholic communities are "true Churches" and not just rites within the Catholic Church.[18] There are 14 other Churches in the United States (23 within the global Catholic Church) which are in communion with Rome, fully recognized and valid in the eyes of the Catholic Church. They have their own bishops and eparchies. The largest of these communities in the U.S. is the Chaldean Catholic Church.[19] Most of these Churches are of Eastern European and Middle Eastern origin. Eastern Catholic Churches are distinguished from Eastern Orthodox, identifiable by their usage of the term Catholic.[20]

Personnel

The Church employs people in a variety of leadership and service roles. Its ministers consist of ordained clergy (bishops, deacons, and presbyters (priests)) and non-ordained lay ecclesial ministers, theologians, and catechists.

Some Christians, both lay and clergy, live in a form of consecrated life, rather than in marriage. This includes a wide range of relationships, from monastic (monks and nuns), to mendicant (friars and sisters), apostolic, secular and lay institutes. While many of these also serve in some form of ministry, above, others are in secular careers, within or without the Church. Consecrated life - in and of itself - does not make a person a part of the clergy or a minister of the Church, nor even one of its employees.

Additionally, many lay people are employed in "secular" careers in support of Church institutions, including educators, health care professionals, finance and human resources experts, lawyers, and others.

Bishops

Leadership of the Catholic Church in the United States is provided by the bishops, individually for their own dioceses, and collectively through the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. There are some mid-level groupings of bishops, such as ecclesiastical provinces (often covering a state) and the fourteen geographic regions of the USCCB, but these have little significance for most purposes.

The ordinary office for a bishop is to be the bishop of a particular diocese, its chief pastor and minister, usually geographically defined and incorporating, on average, about 350,000 Catholic Christians. In canon law, the bishop leading a particular diocese, or similar office, is called an "ordinary" (i.e., he has ordinary jurisdiction in this territory or grouping of Christians).

There are two non-geographic dioceses, called "ordinariates", one for military personnel and one for former Anglicans who are in full communion with the Catholic Church.

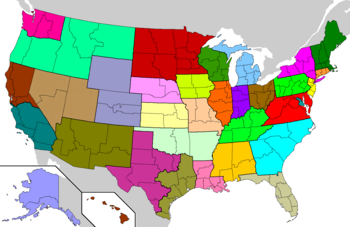

Dioceses are grouped together geographically into provinces, usually within a state, part of a state, or multiple states together (see map below). A province comprises several dioceses which look to one ordinary bishop (usually of the most populous or historically influential diocese/city) for guidance and leadership. This lead bishop is their archbishop and his diocese is the archdiocese. The archbishop is called the 'metropolitan' bishop who oversees his brother 'suffragan' bishops. The subordinate dioceses are likewise called suffragan dioceses.

Some larger dioceses have additional bishops assisting the diocesan bishop, and these are called "auxiliary" bishops.

Additionally, some bishops are called to advise and assist the bishop of Rome, the pope, in a particular way, either as an additional responsibility on top of their diocesan office, or sometimes as a full-time position in the Roman Curia or related institution serving the universal church. These are called cardinals, because they are 'incardinated' onto a second diocese (Rome).

There are 428 active and retired Catholic bishops in the United States:

255 active bishops:

- 36 archbishops

- 144 diocesan bishops

- 67 auxiliary bishops

- 8 apostolic or diocesan administrators

173 retired bishops:

- 33 retired archbishops

- 95 retired diocesan bishops

- 45 retired auxiliary bishops

Cardinals

There are 17 U.S. cardinals.

Six archdioceses are currently led by archbishops who have been created cardinals:

- Blase J. Cupich - Chicago

- Daniel DiNardo - Galveston-Houston

- Timothy M. Dolan - New York

- Seán Patrick O'Malley - Boston

- Joseph W. Tobin - Newark

- Donald Wuerl - Washington, D.C.

Four cardinals are in service to the pope, in the Roman Curia or related offices:

- Raymond Leo Burke - patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Kevin Farrell - Prefect of the Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life

- James Michael Harvey - Archpriest of the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls

- Edwin Frederick O'Brien - Grand Master of the Equestrian Order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem

Seven cardinals are retired:

- Bernard Francis Law - Archpriest Emeritus of Basilica of Saint Mary Major, Rome and Archbishop Emeritus of Boston

- William Levada - Prefect Emeritus, Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and Archbishop Emeritus of San Francisco

- Roger Mahony - Archbishop Emeritus of Los Angeles

- Adam Maida - Archbishop Emeritus of Detroit

- Theodore Edgar McCarrick - Archbishop Emeritus of Washington, D.C.

- Justin Francis Rigali - Archbishop Emeritus of Philadelphia

- James Stafford - Major Penitentiary Emeritus of the Apostolic Penitentiary and Archbishop Emeritus of Denver

Clergy and ministers

As of 2016,[21] there were approximately 100,000 clergy and ministers employed by the Church in the United States, including:

- 37,192 presbyters (priests)

- 25,760 diocesan

- 11,432 religious/consecrated

- 19,053 deacons

- 18,173 ordinary (permanent)

- 880 extraordinary (transitional)

- 39,651 lay ecclesial ministers[22]

- 23,149 diocesan

- 16,502 religious/consecrated

There are also approximately 30,000 seminarians/students in formation for ministry:

- 3,520 candidates for prebsyterate

- 2,297 candidates for diaconate

- 23,681 candidates for lay ecclesial ministry

Secular employees

The 630 Catholic hospitals in the U.S. have a combined budget of $101.7bn, and employe 641,030 full-time equivalent staff.[23]

The 6,525 Catholic primary and secondary schools in the U.S. employee 151,101 full-time equivalent staff, 97.2% of whom are lay and 2.3% are consecrated, and 0.5% are ordained.[24]

The 261 Catholic institutions of higher (tertiary) education in the U.S. employe approximately 250,000 full-time equivalent staff, including faculty, administrators, and support staff.[25]

Overall, it employs more than one million employees with an operating budget of nearly $100 billion to run parishes, diocesan primary and secondary schools, nursing homes, retreat centers, diocesan hospitals, and other charitable institutions.[26]

Approved translations of the Bible

USCCB approved translations

1991–present:

- New American Bible, Revised Edition

- Books of the New Testament, Alba House

- Contemporary English Version - New Testament, First Edition, American Bible Society

- Contemporary English Version - Book of Psalms, American Bible Society

- Contemporary English Version - Book of Proverbs, American Bible Society

- The Grail Psalter (Inclusive Language Version), G.I.A. Publications

- New American Bible, Revised Old Testament

- New Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition, National Council of Churches

- The Psalms, Alba House

- The Psalms (New International Version) - St. Joseph Catholic Edition, Catholic Book Publishing Company

- The Psalms - St. Joseph New Catholic Version, Catholic Book Publishing Company

- Revised Psalms of the New American Bible

- Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition, National Council of Churches

- Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition, National Council of Churches

- So You May Believe, A Translation of the Four Gospels, Alba House

- Today's English Version, Second Edition, American Bible Society

- Translation for Early Youth, A Translation of the New Testament for Children, Contemporary English Version, American Bible Society

Institutions

Parochial schools

By the middle of the 19th century, the Catholics in larger cities started building their own parochial school system. The main impetus was fear that exposure to Protestant teachers in the public schools, and Protestant fellow students, would lead to a loss of faith. Protestants reacted by strong opposition to any public funding of parochial schools.[27] The Catholics nevertheless built their elementary schools, parish by parish, using very low paid sisters as teachers.[28]

In the classrooms, the highest priorities were piety, orthodoxy, and strict discipline. Knowledge of the subject matter was a minor concern, and in the late 19th century few of the teachers in parochial (or secular) schools had gone beyond the 8th grade themselves. The sisters came from numerous denominations, and there was no effort to provide joint teachers training programs. The bishops were indifferent. Finally around 1911, led by the Catholic University in Washington, Catholic colleges began summer institutes to train the sisters in pedagogical techniques. Long past World War II, the Catholic schools were noted for inferior plants compared to the public schools, and less well-trained teachers. The teachers were selected for religiosity, not teaching skills; the outcome was pious children and a reduced risk of marriage to Protestants.[29]

Universities and colleges

According to the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities in 2011, there are approximately 230 Catholic universities and colleges in the United States with nearly 1 million students and some 65,000 professors.[30] In 2016, the number of tertiary schools fell to 227, while the number of students also fell to 798,006.[31] The national university of the Church, founded by the nation's bishops in 1887, is The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. The first Catholic institution of higher learning established in the United States was Georgetown University in 1789.[32]

Seminaries

According to the 2016 Official Catholic Directory, as of 2016 there were 243 seminaries with 4,785 students in the United States; 3,629 diocesan seminarians and 1,456 religious seminarians. By the official 2017 statistics, there are 5,050 seminarians (3,694 diocesan and 1,356 religious) in the United States. In addition, the American Catholic bishops oversee the Pontifical North American College for American seminarians and priests studying at one of the Pontifical Universities in Rome.

Healthcare system

In 2002, Catholic health care systems, overseeing 625 hospitals with a combined revenue of 30 billion dollars, comprised the nation's largest group of nonprofit systems.[33] In 2008, the cost of running these hospitals had risen to $84.6 billion, including the $5.7 billion they donate.[34] According to the Catholic Health Association of the United States, 60 health care systems, on average, admit one in six patients nationwide each year.[35]

Catholic Charities

Catholic Charities is active as one of the largest voluntary social service networks in the United States. In 2009, it welcomed in New Jersey the 50,000th refugee to come to the United States from Burma. Likewise, the US Bishops' Migration and Refugee Services has resettled 14,846 refugees from Burma since 2006.[36] In 2010 Catholic Charities USA was one of only four charities among the top 400 charitable organizations to witness an increase in donations in 2009, according to a survey conducted by The Chronicle of Philanthropy.[37]

Catholic Church and labor

The church had a role in shaping the U.S. labor movement, due to the involvement of priests like Charles Owen Rice and John P. Boland. The activism of Msgr. Geno Baroni was instrumental in creating the Catholic Campaign for Human Development.

Demographics

There are 70,412,021 registered Catholics in the United States (22% of the US population) as of 2017, according to the American bishops' count in their Official Catholic Directory 2016.[1] This count primarily rests on the parish assessment tax which pastors evaluate yearly according to the number of registered members and contributors. Estimates of the overall American Catholic population from recent years generally range around 20% to 28%. According to Albert J. Menedez, research director of "Americans for Religious Liberty," many Americans continue to call themselves Catholic but "do not register at local parishes for a variety of reasons."[38] According to a survey of 35,556 American residents (released in 2008 by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life), 23.9% of Americans identify themselves as Catholic (approximately 72 million of a national population of 306 million residents).[39] The study notes that 10% of those people who identify themselves as Protestant in the interview are former Catholics and 8% of those who identity themselves as Catholic are former Protestants.[40] Nationally, more parishes have opened than closed.

The northeastern quadrant of the US (i.e., New England, Mid-Atlantic, East North Central, and West North Central) has seen a decline in the number of parishes since 1970, but parish numbers are up in the other five regions (i.e., South Atlantic, East South Central, West South Central, Pacific, and Mountain regions).[41] Catholics in the US are about 6% of the church's total worldwide 1.2 billion membership.

A poll by The Barna Group in 2004 found Catholic ethnicity to be 60% non-Hispanic white (generally of mixed ethnicity, but almost always includes at least one Catholic ethnicity such as Irish, Italian, German, Polish, or French), 31% Hispanic of any nationality (mostly Mexicans), 4% Black [including black Latino and Caribbean], and 5% other ethnicity (mostly Filipinos and other Asian Americans, Americans who are multiracial and have mixed ethnicities, and American Indians).[42] Among the non-Hispanic whites, about 16 million Catholics identify as being of Irish descent, about 13 million as German, about 12 million as Italian, about 7 million as Polish, and about 5 million as French (note that many identify with more than one ethnicity). The roughly 6 million Catholics who are converts (mainly from Protestantism, with a smaller number from irreligion or other religions) are also mostly non-Hispanic white, including many people of British, Dutch, and Scandinavian ancestry.

Between 1990 and 2008, there were 11 million additional Catholics. The growth in the Latino population accounted for 9 million of these. They comprised 32% of all American Catholics in 2008 as opposed to 20% in 1990.[43] The percentage of Hispanics who identified as Catholic dropped from 67% in 2010 to 55% in 2013.[44]

According to a more recent Pew Forum report which examined American religiosity in 2014 and compared it to 2007,[45] there were 50.9 million adult Catholics as of 2014 (excluding children under 18), forming about 20.8% of the U.S. population, down from 54.3 million and 23.9% in 2007. Pew also found that the Catholic population is aging, forming a higher percentage of the elderly population than the young, and retention rates are also worse among the young. About 41% of those raised Catholic have left the faith, about half of these to the unaffiliated population and a quarter to evangelical and other Protestantism. Conversions to Catholicism are rare, with 90% of current Catholics being raised in the religion; 7% of current Catholics are ex-Protestants, 2% were raised unaffiliated, and 1% in other religions (Orthodox Christian, Mormon or other nontrinitarian, Buddhist, Muslim, etc.), with Jews and Hindus least likely to become Catholic of all the religious groups surveyed. Overall, Catholicism has by far the worst net conversion balance of any major religious group, with a high conversion rate out of the faith and a low rate into it; by contrast, most other religions have in- and out-conversion rates that roughly balance, whether high or low. By race, 59% of Catholics are non-Hispanic white, 34% Hispanic, 3% black, 3% Asian, and 2% mixed or Native American. Conversely, 19% of non-Hispanic whites are Catholic in 2014 (down from 22% in 2007), whereas 48% of Hispanics are (versus 58% in 2007). In 2015, Hispanics are 38%, while blacks and Asians are still at 3% each.[46]

Catholicism by state

Politics

There had never been a Catholic religious party in the United States, either local, state or national, similar to Christian Democratic parties in Europe and Latin America, until the formation of the Christian Democracy Party USA in 2011, now the American Solidarity Party. Since the election of the Catholic John F. Kennedy as President in 1960, Catholics have split about 50-50 between the two major parties. On social issues the Catholic Church takes strong positions against abortion, which was partly legalized in 1973 by the Supreme Court, and same-sex marriage, which was fully legalized in June 2015. The Church also condemns embryo-destroying research and in vitro fertilization as immoral. The Church is allied with conservative evangelicals and other Protestants on these issues. However, the Catholic Church throughout its history has taken special concern for all vulnerable groups. This has led to progressive alliances, as well, with the church championing causes such as a strong welfare state, unionization,[48] immigration for those fleeing economic or political hardship, opposition to capital punishment,[49] environmental stewardship,[50] gun control,[51] opposition and critical evaluation of modern warfare.[52] The Catholic Church's teachings, coming from the perspective of a global church, do not conform easily to the American political binary of "liberals" and "conservatives." American Catholics are in some cases at odds with church hierarchy on doctrinal issues of political importance.

History

Early period to 1800

There were small Catholic settlements in Spanish and French colonies, especially in California, New Mexico and Louisiana. Apart from Louisiana, they had only a small role in the history of the Church in the United States.

Anti-Catholicism was official government policy for the English who settled the colonies along the Atlantic seaboard.[53] Maryland was founded by a Catholic, Lord Baltimore as the first 'non-denominational' colony and was the first to accommodate Catholics. In 1650, the Puritans in the colony rebelled and repealed the Act of Toleration. Catholicism was outlawed and Catholic priests were hunted and exiled. By 1658, the Act of Toleration was reinstated and Maryland became the center of Catholicism into the mid-19th century. In 1689 Puritans rebelled and again repealed the Maryland Toleration Act. Freedom of religion returned with the American Revolution. By the time of the American Revolution in the 1770s, Catholics formed 1.6%, or 40,000 persons, white and black of the 2.5 million population of the thirteen colonies.[54][55] Perhaps a majority lived in Maryland where they may have been 10% of the colony's inhabitants 230,ooo inhabitants.

After the Revolution Rome made entirely new arrangements for the creation of an American diocese under American bishops.[56][57] Numerous Catholics served in the American army and the new nation had very close ties with Catholic France.[58] General George Washington insisted on toleration; for example, issued strict orders in 1775 that "Pope's Day," the colonial equivalent of Guy Fawkes Night, was not to be celebrated. Foreign Catholics played major military roles, especially Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, Charles Hector, comte d'Estaing and Tadeusz Kościuszko.[59]

In 1787 two Catholics, Daniel Carroll and Thomas Fitzsimons, helped draft the new United States Constitution.[60] In 1791, the First Amendment stated, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

John Carroll was appointed by the Vatican as Prefect Apostolic, making him superior of the missionary church in the thirteen states, and to the first plans for Georgetown University. He became the first American bishop in 1789.

19th century (1800–1900)

The numbers of Catholics surged starting in the 1840s as German, Irish, and other Catholics came in large numbers. After 1890 Italians and Poles comprised the largest numbers of new Catholics, but many countries in Europe contributed, as did Quebec. By 1850, Catholics had become the country's largest single denomination. Between 1860 and 1890, their population tripled to seven million.

Some short-lived anti-Catholic political movements appeared: the Know Nothings in the 1840s, American Protective Association in the 1890s, and the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, were active in the United States. Animosity by Protestants waned as Catholics demonstrated their patriotism in war, their commitment to charity, and their dedication to democratic values.[61]

The bishops began at standardizing discipline in the American Church with the convocation of the Plenary Councils of Baltimore in 1852, 1866 and 1884. These councils resulted in the promulgation of the Baltimore Catechism and the establishment of The Catholic University of America.

After the Civil War, Catholics were legally treated equally to other religions under the US Constitution with the passage of the 14th Amendment.[62]

Jesuit priests who had been expelled from Europe found a new base in the U.S. They were noted for their schools and colleges, such as Boston College, Georgetown University, and several Loyola Colleges.[63]

In the 1890s the Americanism controversy roiled senior officials. The Vatican suspected there was too much liberalism in the American Church, and the result was a turn to conservative theology as the Irish bishops increasingly demonstrated their total loyalty to the Pope, and traces of liberal thought in the Catholic colleges were suppressed.[64][65]

Nuns and sisters

Nuns and sisters played a major role in American religion, education, nursing and social work since the early 19th century. In Catholic Europe, convents were heavily endowed over the centuries, and were sponsored by the aristocracy. There were very few rich American Catholics, and no aristocrats. Religious orders were founded by entrepreneurial women who saw a need and an opportunity, and were staffed by devout women from poor families. The numbers grew rapidly, from 900 sisters in 15 communities in 1840, 50,000 in 170 orders in 1900, and 135,000 in 300 different orders by 1930. Starting in 1820, the sisters always outnumbered the priests and brothers.[66] Their numbers peaked in 1965 at 180,000 then plunged to 56,000 in 2010. Many women left their orders, and few new members were added.[67]

On April 8, 2008, Cardinal William Levada, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under Pope Benedict XVI, met with LCWR leaders in Rome and communicated that the CDF would conduct a doctrinal assessment of the LCWR, expressing concern that the nuns were expressing radical feminist views. According to Laurie Goodstein, the controversial investigation, which was viewed by many U.S. Catholics as a "vexing and unjust inquisition of the sisters who ran the church's schools, hospitals and charities" was ultimately closed in 2015 in meeting with Pope Francis.[68]

20th–21st centuries

In the era of intense emigration from the 1840s to 1914, bishops often set up separate parishes for major ethnic grou ps, such as Ireland, Germany, Poland, French Canada and Italy. In Iowa, the development of the Archdiocese of Dubuque, the work of Bishop Loras and the building of St. Raphael's Cathedral, to meet the needs of Germans and Irish, is illustrative. By the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Catholic. Modern Catholic immigrants come to the United States from the Philippines, Poland and Latin America, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism and diversity has influenced the conduct of Catholicism in the United States. For example, some dioceses say the Mass in both English and Spanish.

Sociologist Andrew Greeley, an ordained Catholic priest at the University of Chicago, undertook a series of national surveys of Catholics in the late 20th century. He published hundreds of books and articles, both technical and popular. His biographer summarizes his interpretation:

- He argued for the continued salience of ethnicity in American life and the distinctiveness of the Catholic religious imagination. Catholics differed from other Americans, he explained in a variety of publications, by their tendency to think in "sacramental" terms, imagining God as present in a world that was revelatory rather than bleak. The poetic elements in the Catholic tradition--its stories, imagery, and rituals--kept most Catholics in the fold, according to Greeley, whatever their disagreements with particular aspects of church discipline or doctrine. But Greeley also insisted on the disastrous impact of Humanae Vitae, the 1968 papal encyclical upholding the Catholic ban on contraception, holding it almost solely responsible for a sharp decline in weekly Mass attendance between 1968 and 1975. He believed that lay Catholics understood far better than their bishops that sex in marriage was intended by God to be joyous and playful, a true means of grace.[69]

In 1965, 71% of Catholics attended Mass.[70][when?]

In the later 20th century "[...] the Catholic Church in the United States became the subject of controversy due to allegations of clerical child abuse of children and adolescents, of episcopal negligence in arresting these crimes, and of numerous civil suits that cost Catholic dioceses hundreds of millions of dollars in damages."[71] Because of this, higher scrutiny and governance, as well as protective policies and diocesan investigation into seminaries have been enacted to correct these former abuses of power, and safeguard parishioners and the Church from further abuses and scandals.

One initiative is the "National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management" (NLRCM), a lay-led group born in the wake of the sexual abuse scandal and dedicated to bringing better administrative practices to 194 dioceses that include 19,000 parishes nationwide with some 35,000 lay ecclesial ministers who log 20 hours or more a week in these parishes.[72]

In 2008, 17% of Catholics attended Mass.[70][when?]

Recently John Micklethwait, editor of The Economist and co-author of God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World, said that American Catholicism, which he describes in his book as "arguably the most striking Evangelical success story of the second half of the nineteenth century," has competed quite happily "without losing any of its basic characteristics." It has thrived in America's "pluralism."[73]

In 2011, an estimated 26 million American Catholics were "fallen-away", that is, not practicing their faith. Some religious commentators commonly refer to them as "the second largest religious denomination in the United States."[74] Recent Pew Research survey results in 2014 show about 31.7% of American adults were raised Catholic, while 41% of them no longer identify as Catholic. Thus, 12.9% of those adults have left Catholicism for other religious groups or no affiliation at all.[45]

In a 2015 survey by researchers at Georgetown University, Americans who self identify as Catholic, including those who do not attend Mass regularly, numbered 81.6 million or 25% of the population. 68.1 million or 20% of the American population are Catholics tied to a specific parish. About 25% of US Catholics say they attend Masses once a week or more, and about 38% went at least once a month. The study found that the number of US Catholics has increased by 3 to 6% each decade since 1965, and that the Catholic Church is "the most diverse in terms of race and ethnicity in the US," with Hispanics accounting for 38% of Catholics and blacks and Asians 3% each.[46] Only 2 percent of American Catholics go to confession on a regular basis, while three-quarters of them go to confession once a year or less often.[75]

Servants of God and those declared venerable, beatified, and canonized saints

The following are some notable Americans declared as Servants of God, venerables, beatified, and canonized saints:

- Servants of God

- Venerables

- Saints

Top eight pilgrimage destinations in the United States

According to The Official Catholic Directory, the following are the top eight Catholic pilgrimage sites in the United States:[76]

- National Shrine of the North American Martyrs (Auriesville, New York)

- Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Baltimore, Maryland)

- El Santuario de Chimayo (Chimayo, New Mexico, north of Santa Fe)

- Basilica of the National Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton (Emmitsburg, Maryland)

- Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament of Our Lady of the Angels (Hanceville, Alabama)

- Basilica of Our Lady of Victory (Lackawanna, New York)

- National Shrine of Saint John Neumann (in St. Peter the Apostle Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (Washington, D.C.)

Notable American Catholics

See also

- 19th century history of the Catholic Church in the United States

- 20th century history of the Catholic Church in the United States

- American Catholic literature

- Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Directory

- Catholic sisters and nuns in the United States

- Christianity in the United States

- Global organisation of the Catholic Church

- Index of Catholic Church articles

- List of Catholic bishops of the United States

- List of Catholic cathedrals in the United States

- List of Catholic churches in the United States

- List of Catholic dioceses in the United States

- Outline of Catholicism

References

- ^ a b "Diocese of Reno, 2016–2017 Directory" (PDF). p. 72.

Total Catholic Population [...] 70,412,021

- ^ http://cara.georgetown.edu/CARAServices/requestedchurchstats.html

- ^ David Neff, "Global Is Now Local: Princeton's Robert Wuthnow says American congregations are more international than ever," Christianity Today, June 2009, 39.

- ^ Richard Middleton, Colonial America (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 387–406.

- ^ American Horizons: U.S. History in a Global Context, edited by Michael Schaller, Robert Schulzinger, etc. (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016,14), 33

- ^ Middleton,406–14

- ^ Breidenbach, Michael (July 2016). "Conciliarism and the American Founding". William and Mary Quarterly. 73 (3): 467. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.73.3.0467. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.73.3.0467.

- ^ J. A. Birkhaeuser, [1] "1893 History of the church: from its first establishment to our own times. Designed for the use of ecclesiastical seminaries and colleges, Volume 3"

- ^ http://blog.adw.org/2010/12/is-the-bottom-really-falling-out-of-catholic-mass-attendance-a-recent-cara-survey-ponders-the-question/

- ^ http://www.economist.com/node/5442147

- ^ Burke, Daniel. "What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated". CNN. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ http://www.pewforum.org/2015/01/05/faith-on-the-hill/

- ^ https://opendata.socrata.com/dataset/World-s-Largest-Cathedrals/sfaz-u3mt

- ^ "Diocese of Reno, 2016–2017 Directory" (PDF). p. 72.

Parishes [...] 17,651

- ^ Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches 2010(Nashville: Abington Press, 2010), 12.

- ^ On July 14, 2010, Pope Benedict XVI erected the Syro-Malankara Catholic Exarchate in the United States.

- ^ Cheney, David M. "Catholic Church in Puerto Rico". Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ Richard McBrien, THE CHURCH/THE EVOLUTION OF CATHOLICISM (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), 450. Also see: BASIC VATICAN COUNCIL II: THE BASIC SIXTEEN DOCUMENTS (Costello Publishing, 1996).

- ^ Ronald Roberson. "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2009" (PDF). Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Information sourced from Annuario Pontificio 2009 edition. Retrieved November 2009

- ^ McBrien, 241,281, 365,450

- ^ "Frequently Requested Church Statistics"

- ^ This number is conservative, as it only counts those in parish ministry, but there are many in deanery, diocesan, or chaplaincy work

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Thomas Healy, "A Blueprint for Change," America 26 September 2005, 14.

- ^ Thomas E. Buckley, "A Mandate for Anti-Catholicism: The Blaine Amendment," America 27 September 2004, 18–21.

- ^ Jay P. Dolan, The American Catholic Experience (1985) pp 262-74

- ^ Jay P. Dolan, The American Catholic Experience (1985) pp 286-91

- ^ Jerry Filteau, "Higher education leaders commit to strengthening Catholic identity," NATIONAL CATHOLIC REPORTER, Vol 47, No. 9, February 18, 2011, 1

- ^ "Diocese of Reno, 2016–2017 Directory" (PDF). p. 72.

'Colleges and Universities [...] 217' and 'Total Students [...] 798,006'

- ^ "Georgetown University: History". Georgetown University.

- ^ Arthur Jones, "Catholic health care aims to make 'Catholic' a brand name," National Catholic Reporter 18 July 2003, 8.

- ^ Walsh, Sister Mary Ann (28 August – 10 September 2009). "Catholic health care for a broken arm; a cast and new shoes". Orlando, Florida: The Florida Catholic. p. A11.

- ^ Alice Popovici, "Keeping Catholic priorities on the table," National Catholic Reporter 26 June 2009, 7.

- ^ "50,000th refugee settled," National Catholic Reporter 24 July 2009, 3.

- ^ Michael Sean Winters, "Catholic giving bucks national trend," THE TABLET, 23 October 2010, 32.

- ^ Albert J. Mendedez, "American Catholics, A Social and Political Portrait," THE HUMANIST, September/October, 1993, 17-20.

- ^ Michael Paulson, "US religious identity is rapidly changing," Boston Globe, February 26, 2008, 1

- ^ Ted Olsen, "Go Figure," Christianity Today, April, 2008, 15

- ^ Dennis Sadowski, "When parishes close, there is more to deal with than just logistics," National Catholic Reporter 7 July 2009, 6.

- ^ [5] Archived March 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zapor, Patricia (March 25 – April 8, 2010). "Study finds Latinos who leave their churches are choosing no faith". Orlando, Florida: the Florida Catholic. pp. A11.

- ^ http://www.pewforum.org/2014/05/07/the-shifting-religious-identity-of-latinos-in-the-united-states/

- ^ a b "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research. May 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "Immigration boosting US Catholic numbers". The Manila Times. Agence France-Presse. September 23, 2015.

- ^ See each state's Religious Demographic section

- ^ Rerum novarum

- ^ Catholic Church and capital punishment

- ^ Stewardship of God's Creation, Major themes from Catholic Social Teaching, Office for Social Justice, Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

- ^ http://www.uscatholic.org/blog/201304/gun-control-pro-life-issue-27145

- ^ See The Challenge of Peace: God's Promise and Our Response

- ^ Ellis, John Tracy (1956). American Catholicism.

- ^ Richard Middleton, Colonial America (2003), 95-100, 145, 158, 159, 349n

- ^ Maynard, 126-126

- ^ Breidenbach, Michael (July 2016). "Conciliarism and the American Founding". William and Mary Quarterly. 73 (3): 487–88. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.73.3.0467. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.73.3.0467.

- ^ Theodore Maynard, The Story of American Catholicism (1960), 155.

- ^ Maynard, 126-42

- ^ Maynard, 140–41.

- ^ Maynard, 145–46.

- ^ Tyler Anbinder, "Nativism and prejudice against immigrants" in Reed Ueda, ed., A companion to American immigration (2006) pp: 177-201.

- ^ "Quotation, Overview, and the Constitutions of Arkansas & Maryland". Ontario consultants on religious tolerance. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ^ Peter McDonough, Men astutely trained: A history of the Jesuits in the American Century (2008).

- ^ James Hennessy, S.J., American Catholics: A history of the Roman Catholic community in the United States (1981) pp 194-203

- ^ Thomas T. McAvoy, "The Catholic Minority after the Americanist Controversy, 1899–1917: A Survey," Review of Politics, Jan 1959, Vol. 21 Issue 1, pp 53–82 in JSTOR

- ^ James M. O'Toole, The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America (2008) p 104

- ^ Margaret M. McGuinness, Called to Serve (2013), ch 8

- ^ Goodstein, Laurie (2015-04-16). "Vatican ends battle with U.S. Catholic nuns' group". nytimes.com. New York: The New York Times.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Leslie Woodcock Tentler, "Greeley, Andrew Moran" in American National Biography Online April 2016; Access Apr 30 2017

- ^ a b Peterson, Tom (2013). Catholics come home. New York City: Image. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-385-34717-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Patrick W. Carey, Catholics in America. A History, Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger, 2004, p. 141

- ^ David Gibson, "Declaration of interdependence," The Tablet 4 July 2009, 8–9.

- ^ Austin Ivereigh, "God Makes a Comeback: An Interview with John Micklethwait, America, 5 October 2009, 13–14.

- ^ Karen Mahoney (2011-02-23). "Why won't my kids go to church". Archdiocese of Milwaukee Catholic Herald.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ AMERICAN SIN: WHY POPE FRANCIS' MERCY IS NOT OUR MERCY Religion Dispatches, February 8, 2016

- ^ The Official Catholic Directory 2009–2010 Pilgrimage Guide. (New Providence, N.J.: Kenedy and Sons, 2009), 55–63.

Further reading

- Abell, Aaron. American Catholicism and Social Action: A Search for Social Justice, 1865–1950 (Garden City, NY: Hanover House, 1960).

- Bales, Susan Ridgley. When I Was a Child: Children's Interpretations of First Communion (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2005).

- Carroll, Michael P. American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- Coburn, Carol K. and Martha Smith. Spirited Lives: How Nuns Shaped Catholic Culture and American Life, 1836–1920 (1999) pp 129–58 excerpt and text search

- Curan, Robert Emmett. Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 2012.

- D'Antonio, William V., James D. Davidson, Dean R. Hoge, and Katherine Meyer. American Catholics: Gender, Generation, and Commitment (Huntington, Ind.: Our Sunday Visitor Visitor Publishing Press, 2001).

- Deck, Allan Figueroa, S.J. The Second Wave: Hispanic Ministry and the Evangelization of Cultures (New York: Paulist, 1989).

- Dolan, Jay P. The Immigrant Church: New York Irish and German Catholics, 1815–1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975).

- Dolan, Jay P. In Search of an American Catholicism: A History of Religion and Culture in Tension (2003)

- Donovan, Grace. "Immigrant Nuns: Their Participation in the Process of Americanization," in Catholic Historical Review 77, 1991, 194–208.

- Ellis, J.T. American Catholicism 2nd ed.(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969).

- Finke, Roger. "An Orderly Return to Tradition: Explaining Membership Growth in Catholic Religious Orders," in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion , 36, 1997, 218–30.

- Fogarty, Gerald P., S.J. Commonwealth Catholicism: A History of the Catholic Church in Virginia, ISBN 978-0-268-02264-8.

- Garraghan, Gilbert J. The Jesuits of the Middle United States Vol. II (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1984).

- Greeley, Andrew. "The Demography of American Catholics, 1965–1990" in The Sociology of Andrew Greeley (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994).

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995). Interesting note on Afro-Creole Catholic culture.

- Horgan, Paul. Lamy of Santa Fe (Toronto: McGraw-Hill, 1975).

- Jonas, Thomas J. The Divided Mind: American Catholic Evangelists in the 1890s (New York: Garland Press, 1988).

- Marty, Martin E. Modern American Religion, Vol. 1: The Irony of It All, 1893–1919 (1986); Modern American Religion. Vol. 2: The Noise of Conflict, 1919–1941 (1991); Modern American Religion, Volume 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941–1960 (1999), perspective by leading Protestant historian

- McGuinness Margaret M. Called to Serve: A History of Nuns in America (New York University Press, 2013) 266 pages; excerpt and text search

- McDermott, Scott. Charles Carroll of Carrollton—Faithful Revolutionary ISBN 1-889334-68-5.

- McKevitt, Gerald. Brokers of Culture: Italian Jesuits in the American West, 1848–1919 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

- McMullen, Joanne Halleran and Jon Parrish Peede, eds. Inside the Church of Flannery O'Connor: Sacrament, Sacramental, and the Sacred in Her Fiction (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2007).

- Maynard, Theodore The Story of American Catholicism, Volumes I and II (New York: Macmillan Company, 1960).

- Morris, Charles R. American Catholic: The Saints and Sinners Who Built America's Most Powerful Church (1998), a popular history

- O'Toole, James M. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America (2008)

- Poyo, Gerald E. Cuban Catholics in the United States, 1960–1980: Exile and Integration (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2007).

- Sanders, James W. The Education of an urban Minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833–1965 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

- Schroth, Raymond A. The American Jesuits: A History (New York: New York University Press, 2007).

- Schultze, George E. Strangers in a Foreign Land: The Organizing of Catholic Latinos in the United States (Lanham, Md:Lexington, 2007).

- Stepsis, Ursula and Dolores Liptak. Pioneer Healers: The History of Women Religious in American Health Care (1989) 375pp

- Walch, Timothy. Parish School: American Catholic Parochial Education from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 1996).

- Weber, David J. The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992). on Spanish missionaries

Historiography

- Gleason, Philip. "The Historiography of American Catholicism as Reflected in The Catholic Historical Review, 1915–2015." Catholic Historical Review 101#2 (2015) pp: 156-222. online

Primary sources

- Ellis, John Tracy. Documents of American Catholic History 2nd ed. (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co., 1956).

External links

- Global Catholic Statistics: 1905 and Today by Albert J. Fritsch, SJ, PhD

- Largest religious groups in the United States