Wesley Clark

Wesley Clark | |

|---|---|

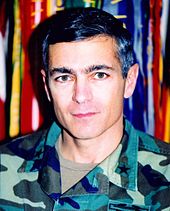

Official portrait, c. 1997–2000 | |

| Birth name | Wesley J. Kanne |

| Born | December 23, 1944 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1966–2000 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Supreme Allied Commander Europe United States Southern Command |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | See all |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy (BS) Magdalen College, Oxford (BA) U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (MMAS) |

| Spouse(s) |

Gertrude Kingston (m. 1967) |

| Signature | |

| Website | http://wesleykclark.com/ |

Wesley Kanne Clark (born Wesley J. Kanne, December 23, 1944) is a retired United States Army officer. He graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1966 at West Point and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford, where he obtained a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. He later graduated from the Command and General Staff College with a master's degree in military science. He commanded an infantry company in the Vietnam War, where he was shot four times and awarded a Silver Star for gallantry in combat. Clark served as the Supreme Allied Commander Europe of NATO from 1997 to 2000, commanding Operation Allied Force during the Kosovo War. He spent 34 years in the U.S. Army, receiving many military decorations, several honorary knighthoods, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 2003, Clark launched his candidacy for the 2004 Democratic Party presidential primaries. After winning only the Oklahoma state primary, he withdrew from the race in February 2004, endorsing and campaigning for the eventual Democratic nominee, John Kerry. Clark leads a political action committee, "WesPAC", which he formed after the 2004 primaries[1][2] and used to support Democratic Party candidates in the 2006 midterm elections.[3] Clark was considered a potential candidate for the Democratic nomination in 2008, but, on September 15, 2007, endorsed Senator Hillary Clinton.[4] After Clinton dropped out of the presidential race, Clark endorsed the then-presumptive Democratic nominee, Barack Obama.[5]

Clark has his own consulting firm, Wesley K. Clark and Associates, and is chairman and CEO of Enverra, a licensed boutique investment bank.[6] He has worked with over 100 private and public companies on energy, security, and financial services. Clark is engaged in business in North America, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and Asia. Between July 2012 and November 2015, he was an honorary special advisor to Romanian prime minister Victor Ponta on economic and security matters.[7][8]

Early life and education

[edit]Clark's father's family was Jewish; his paternal grandparents, Jacob Kanne and Ida Goldman, immigrated to the United States from Belarus, then part of the Russian Empire,[9] in response to the Pale of Settlement and anti-Jewish violence from Russian pogroms. Clark's father, Benjamin Jacob Kanne, graduated from the Chicago-Kent College of Law and served in the U.S. Naval Reserve as an ensign during World War I, although he never participated in combat. Kanne, living in Chicago, became involved with ward politics in the 1920s as a prosecutor and served in local offices. He served as a delegate to the 1932 Democratic National Convention that nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt as the party's presidential candidate[10] (though his name does not appear on the published roll of convention delegates). His mother was of English ancestry and was a Methodist.[11]

Kanne came from the Kohen family line,[12] and Clark's son has characterized Clark's parents' marriage, between his Methodist mother, Veneta (née Updegraff), and his Jewish father, Benjamin Jacob Kanne,[13] as "about as multicultural as you could've gotten in 1944".[14]

Clark was born Wesley J. Kanne in Chicago on December 23, 1944.[15] His father Benjamin died on December 6, 1948; his mother then moved the family to Little Rock, Arkansas. The move was made to escape the cost of living in the city of Chicago, for the support Veneta's family in Arkansas could provide, and her feeling of being an outsider to the religion of the Kanne family.[16] Once in Little Rock, Veneta married Victor Clark, whom she met while working as a secretary at a bank.[17] Victor raised Wesley as his son, and officially adopted him on Wesley's 16th birthday. Wesley's name was changed to Wesley Kanne Clark. Victor Clark's name actually replaced that of Wesley's biological father on his birth certificate, something Wesley would later say that he wished they had not done.[18] Veneta raised Wesley without telling him of his Jewish ancestry to protect him from the anti-Jewish activities of the Ku Klux Klan in the southern U.S.[19] Although his mother was Methodist, Clark chose a Baptist church after moving to Little Rock and continued attending it throughout his childhood.[20]

He graduated from Hall High School with a National Merit Scholarship. He helped take their swim team to the state championship, filling in for a sick teammate by swimming two legs of a relay.[21][22] Clark has often repeated the anecdote that he decided he wanted to go to West Point after meeting a cadet with glasses who told Clark (who wore glasses as well) that one did not need perfect vision to attend West Point as Clark had thought.[14][23] Clark applied, and he was accepted on April 24, 1962.[24]

Military career

[edit]

Clark's military career began July 2, 1962, when he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He later said that Douglas MacArthur's famous "Duty, honor, country" speech was an important influence on his view of the military. The speech was given to the class of 1962 several months before Clark entered West Point, but a recording was played for his class when they first arrived.[14][25]

Clark sat in the front in many of his classes, a position held by the highest performer in class. Clark participated heavily in debate, was consistently within the top 5% of his class as a whole (earning him "Distinguished Cadet" stars on his uniform) and graduated as valedictorian of his class. The valedictorian is allowed to choose their career specialty in the Army, and Clark selected armor. He met Gertrude Kingston (whom he later married) at a USO dance for midshipmen and West Point cadets.[14][25]

Clark applied for a Rhodes Scholarship during his senior year at West Point, and learned in December 1965 that he had been accepted. He spent his summer at the United States Army Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. He completed his master's degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) at Magdalen College at the University of Oxford in August 1968. While he was at Oxford, a Jewish cousin of Clark's who lived in England telephoned him and informed him of his Jewish heritage, having received permission from Veneta Clark. Clark spent three months after graduation at Fort Knox, Kentucky, going through the Armor Officer Basic Course, then went on to Ranger School at Fort Benning. He was promoted to captain and was assigned as commander of the A Company of the 1st Battalion, 63rd Armor, 24th Infantry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas.[26]

Vietnam War

[edit]

Clark was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division and flew to Vietnam in July 1969, during the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. He worked as a staff officer, collecting data and helping in operations planning, and was awarded the Bronze Star for his work with the staff. Clark was then given command of A Company, 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry of the 1st Infantry Division in January 1970. In February, only one month into his command, he was shot four times by a Viet Cong soldier with an AK-47. The wounded Clark shouted orders to his men, who counterattacked and defeated the Viet Cong force. Clark had injuries to his right shoulder, right hand, right hip, and right leg, and was sent to Valley Forge Army Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, to recuperate. He was awarded the Silver Star and the Combat Infantryman Badge for his actions during the encounter.[27]

Clark converted to Catholicism, his wife Gertrude's religion, while in Vietnam. He saw his son, Wesley Clark, Jr., for the first time while at the Valley Forge Hospital.[28] Clark commanded C Company, 6th Battalion, 32nd Armor, 194th Armored Brigade, a company composed of wounded soldiers,[29] at Fort Knox. Clark has said this command is what made him decide to continue his military career past the eight-year commitment required by West Point, which would have concluded in 1974. Clark completed his Armor Officer Advanced Course while at Fort Knox, taking additional elective courses and writing an article that won the Armor Association Writing Award. His next posting was to the office of the Army Chief of Staff in Washington, D.C., where he worked in the "Modern Volunteer Army" program from May to July 1971. He then served as an instructor in the Department of Social Sciences at West Point for three years from July 1971 to 1974.[30][31]

Clark graduated as the Distinguished Graduate and George C. Marshall Award winner from the Command and General Staff College (CGSC), earning his military Master of Arts degree in military science from the CGSC with a thesis on American policies of gradualism in the Vietnam War. Clark's theory was one of applying force swiftly to achieve escalation dominance, a concept that would eventually become established as U.S. national security policy in the form of the Weinberger Doctrine and its successor, the Powell Doctrine. Clark was promoted to major upon his graduation from the CGSC.[32]

Post-Vietnam War

[edit]In 1975, Clark was appointed a White House Fellow in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as a special assistant to its director, James Thomas Lynn. He was one of 14 appointed out of 2,307 applicants.[33] Lynn also gave Clark a six-week assignment to assist John Marsh, then a counselor to the president. Clark was approached during his fellowship to help push for a memorial to Vietnam veterans. He worked with the movement that helped lead to the creation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Clark served in two commands with the 1st Armored Division based in Germany from August 1976 to February 1978, first as S-3 of the 3rd Battalion, 35th Armor and then as S-3 for 3rd Brigade.[30] Clark's brigade commander while in the former position said Clark was "singularly outstanding, notably superb". He was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal for his work with the division.

The brigade commander had also said that "word of Major Clark's exceptional talent spread", and in one case reached the desk of then Supreme Allied Commander Alexander Haig. Haig personally selected Clark to serve as a special assistant on his staff, a post he held from February 1978 to June 1979. While on staff at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), Clark wrote policy reports and coordinated two multinational military exercises. As a result of his work on Haig's staff, Clark was promoted to lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Legion of Merit. After his European post, he moved on to Fort Carson, Colorado, where he served first as the executive officer of the 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division from August 1979 to February 1980, then as the commander of the 1st Battalion, 77th Armor, 4th Infantry Division from February 1980 to July 1982. According to the American journalist David Halberstam, the commander at Fort Carson, then Major General John Hudachek, had a reputation of disliking West Point graduates and fast-rising officers such as Clark.[34][35] Still, Clark was selected first in his year group for full colonel and attended the National War College immediately after his battalion command. Clark graduated in June 1983, and was promoted to full colonel in October 1983.[30][36]

Following his graduation, Clark worked in Washington, D.C., from July 1983 to 1984 in the offices of the Chief and Deputy Chiefs of Staff of the United States Army, earning a second Legion of Merit for his work. He then served as the Operations Group commander at the Fort Irwin Military Reservation from August 1984 to June 1986. He was awarded another Legion of Merit and a Meritorious Service Medal for his work at Fort Irwin and was given a brigade command at Fort Carson in 1986. He commanded the 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division there from April 1986 to March 1988. Veneta Clark, Wesley's mother, died of a heart attack on Mother's Day in 1986. Regarding his term as brigade commander, one of his battalion commanders called Clark the "most brilliant and gifted officer [he'd] ever known".[37] After Fort Carson, Clark returned to the Command and General Staff College to direct and further develop the Battle Command Training Program (BCTP) there until October 1989. The BCTP was created to use escalation training to teach senior officers war-fighting skills, according to the commanding general at the time. On November 1, 1989, Clark was promoted to brigadier general.[30][38]

Clark returned to Fort Irwin and commanded the National Training Center (NTC) from October 1989 to 1991. The Gulf War occurred during Clark's command, and many National Guard divisional round-out brigades trained under his command. Multiple generals commanding American forces in Iraq and Kuwait said Clark's training helped bring about results in the field and that he had successfully begun training a new generation of the military that had moved past Vietnam-era strategy. He was awarded another Legion of Merit for his "personal efforts" that were "instrumental in maintaining" the NTC, according to the citation. He served in a planning post after this, as the deputy chief of staff for concepts, doctrine, and developments at Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) at Fort Monroe, Virginia. While there, he helped the commanding general of TRADOC prepare the army for war and develop new post-Cold War strategies. Clark pushed for technological advancement in the army to establish a digital network for military command, which he called the "digitization of the battlefield".[39] He was promoted to major general in October 1992 at the end of this command.[30][40]

Fort Hood

[edit]Clark's divisional command came with the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Hood, Texas. Clark was in command during three separate deployments of forces from Fort Hood for peacekeeping in Kuwait.

His Officer Evaluation Report (OER) for his command at Fort Hood called him "one of the Army's best and brightest".[41] Clark was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his work at Fort Hood and was promoted to lieutenant general at the end of his command in 1994. Clark's next assignment was an appointment as the Director, Strategic Plans and Policy (J5), on the staff of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), from April 1994 to June 1996.[30][42] In this position, he helped develop and coordinate world-wide US military policy and strategy. He participated with Richard Holbrooke in the Dayton Peace Process, which ended the Bosnian war in former Yugoslavia. During this period, he also participated in "back-stopping" nuclear negotiations in Korea, planning the restoration of democracy in Haiti, shifting the United States Southern Command headquarters from Panama to Miami, imposing tougher restrictions on Saddam Hussein, rewriting the National Military Strategy, and developing Joint Vision 2010 for future US war-fighting.[43]

United States Southern Command

[edit]Army regulations set a so-called "ticking clock" upon promotion to a three-star general, essentially requiring that Clark be promoted to another post within two years from his initial promotion or retire.[44] This deadline ended in 1996 and Clark said he was not optimistic about receiving such a promotion because rumors at the time suggested General Dennis Reimer did not want to recommend him for promotion although "no specific reason was given".[45] According to Clark's book, General Robert H. Scales said that it was likely Clark's reputation for intelligence was responsible for feelings of resentment from other generals. Clark was named to the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) post despite these rumors. Congress approved his promotion to full general in June 1996, and General John M. Shalikashvili signed the order. Clark said he was not the original nominee, but the first officer chosen "hadn't been accepted for some reason".[45][46]

Balkans

[edit]Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]Clark began planning work for responses to the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina upon his appointment in 1994 as the Director, Strategic Plans and Policy (J5) on the JCS staff. While collecting information to outline military options for resolving the conflict, Clark met with Bosnian Serb military leaders including Ratko Mladić, who was later accused of war crimes and genocide. Clark was photographed exchanging hats with Mladić, and the photo drew controversy in the United States. A Washington Post story was published claiming Clark had made the visit despite a warning from the U.S. ambassador.[47] Some Clinton administration members privately said the incident was "like cavorting with Hermann Göring".[48] Clark listed the visit in the itinerary he submitted to the ambassador, but he learned only afterwards that it was not approved. He said there had been no warning and no one had told him to cancel the visit, although two Congressmen called for his dismissal regardless. Clark later said he regretted the exchange,[49] and the issue was ultimately resolved as President Clinton sent a letter defending Clark to Congress and the controversy subsided.[50] Clark said it was his "first experience in the rough and tumble of high visibility ... and a painful few days".[51] Conservative pundit Robert Novak later referred to the hat exchange in a column during Clark's 2004 presidential campaign, citing it as a "problem" with Clark as a candidate.[52]

Clark was sent to Bosnia by Secretary of Defense William Perry to serve as the military member to a diplomatic negotiating team headed by assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke. Holbrooke later described Clark's position as "complicated" because it presented him with future possibilities but "might put him into career-endangering conflicts with more senior officers".[53] While the team was driving along a mountain road during the first week, the road gave way, and one of the vehicles fell over a cliff carrying passengers including Holbrooke's deputy, Robert Frasure, a deputy assistant Secretary of Defense, Joseph Kruzel, and Air Force Colonel Nelson Drew. Following funeral services in Washington, D.C., the negotiations continued and the team eventually reached the Dayton Agreement at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, and later signed it in Paris on December 14, 1995.[54]

Clark returned to the European theater and the Balkans following his USSOUTHCOM position when he was appointed to U.S. European Command in the summer of 1997 by President Clinton. He was, as with SOUTHCOM, not the original nominee for the position. The Army had already selected another general for the post. Because President Clinton and General Shalikashvili believed Clark was the best man for the post, he eventually received the nomination. Shalikashvili noted he "had a very strong role in [Clark's] last two jobs".[55] Clark noted during his confirmation hearing before the Senate Armed Services committee that he believed NATO had shifted since the end of the Cold War from protecting Europe from the Soviet Union to working towards more general stability in the region. Clark also addressed issues related to his then-current command of USSOUTHCOM, such as support for the School of the Americas and his belief that the United States must continue aid to some South American nations to effectively fight the War on Drugs.[49] Clark was quickly confirmed by a voice vote the same day as his confirmation hearing,[56] giving him the command of 109,000 American troops, their 150,000 family members, 50,000 civilians aiding the military, and all American military activities in 89 countries and territories of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.[57] The position made Clark the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), which granted him overall command of NATO military forces in Europe.

Kosovo War

[edit]The largest event of Clark's tenure as SACEUR was NATO's confrontation with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the Kosovo War. On September 22, 1998, the United Nations Security Council introduced Resolution 1199 calling for an end to hostilities in Kosovo, and Richard Holbrooke again tried to negotiate a peace. This process came to an unsuccessful end, however, following the Račak massacre. Then U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright tried to force Yugoslavia into allowing separation of Kosovo with the Rambouillet Agreement, which Yugoslavia refused. Clark was not at the Rambouillet talks. He separately tried to convince Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević by telling him "there's an activation order. And if they tell me to bomb you, I'm going to bomb you good." Clark later alleged that Milošević launched into an emotional tirade against Albanians and said that they'd been "handled" in the 1940s by ethnic cleansing.[58][59]

On orders from President Clinton, Clark started the bombings codenamed Operation Allied Force on March 24, 1999, to try to enforce U.N. Resolution 1199 following Yugoslavia's refusal of the Rambouillet Agreement. However, critics note that Resolution 1199 was a call for cessation of hostilities and did not authorize any organization to take military action. US Secretary of Defense William Cohen felt that Clark had powerful allies at the White House, such as President Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who allowed him to circumvent the Pentagon in promoting his strategic ideas. Clark felt, however, that he was not being included enough in discussions with the National Command Authority, leading him to describe himself as "just a NATO officer who also reported to the United States".[60] This command conflict came to a ceremonial head when Clark was initially not invited to a summit in Washington, D.C., to commemorate NATO's 50th anniversary, despite being its supreme military commander. Clark eventually secured an invitation to the summit, but was told by Cohen to say nothing about ground troops, and Clark agreed.[61]

Clark returned to SHAPE following the summit and briefed the press on the continued bombing operations. A reporter from the Los Angeles Times asked a question about the effect of bombings on Serbian forces, and Clark noted that merely counting the number of opposing troops did not show Milošević's true losses because he was bringing in reinforcements. Many American news organizations capitalized on the remark in a way Clark said "distorted the comment" with headlines such as "NATO Chief Admits Bombs Fail to Stem Serb Operations" in The New York Times. Clark later defended his remarks, saying this was a "complete misunderstanding of my statement and of the facts," and President Clinton agreed that Clark's remarks were misconstrued. Regardless, Clark received a call the following evening from Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Hugh Shelton, who said he had been told by Secretary Cohen to deliver a piece of guidance verbatim: "Get your fucking face off the TV. No more briefings, period. That's it."[63][64]

The bombing campaign received criticism when it bombed the Radio Television of Serbia headquarters on April 23, 1999. The attack which killed sixteen civilian employees was labeled as a war crime by Amnesty International[65] and as an act of terrorism by Noam Chomsky.[66] NATO expressed its justification for the bombing by saying that the station operated as a propaganda tool for the Milošević regime.[67] Operation Allied Force experienced another problem when NATO bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade on May 7, 1999. The operation had been organized against numerous Serbian targets, including "Target 493, the Federal Procurement and Supply Directorate Headquarters", although the intended target building was actually 300 meters away from the targeted area. The embassy was located at this mistaken target, and three Chinese journalists were killed. Clark's intelligence officer called Clark taking full responsibility and offering to resign, but Clark declined, saying it was not the officer's fault. Defense Secretary Cohen and CIA Director George Tenet took responsibility the next day. Tenet would later explain in testimony before the United States House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence on July 22, 1999, that the targeting system used street addresses, which gave inaccurate positions for air bombings. He also said that the various databases of off-limit targets did not have the up-to-date address for the relatively new embassy location.[68][69][70]

The bombing campaign ended on June 10, 1999, on the order of Secretary General of NATO Javier Solana after Milošević complied with conditions the international community had set and Yugoslav forces began to withdraw from Kosovo.[71] United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 was adopted that same day, placing Kosovo under United Nations administration and authorizing a Kosovo peacekeeping force.[72] NATO suffered no combat deaths,[73] although two crew members died in an Apache helicopter crash.[74] A F-117A was downed near the village of Budjanovci. The bombing resulted in an estimated 495 civilian deaths and 820 wounded, as reported to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.[75] Yugoslavia estimated that the number of civilians killed is higher than 2,000 and that more than 5,000 have been wounded.[76] Human Rights Watch estimates the number of civilian deaths due to NATO bombings as somewhere between 488 and 527.[77]

Milošević's term in office in Yugoslavia was coming to an end, and the elections that came on September 24, 2000, were protested due to allegations of fraud and rigged elections. This all came to a head on October 5 in the so-called Bulldozer Revolution. Milošević resigned on October 7. The Democratic Opposition of Serbia won a majority in parliamentary elections that December. Milošević was taken into custody on April 1, 2001, and transferred to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia on June 28 to face charges of war crimes and genocide. Clark was called to testify in a closed session of Milošević's trial in December 2003. He testified on issues ranging from the Srebrenica massacre to conversations Clark had had with Milošević during his career.[78] Some anti-war activist groups also label Clark and Bill Clinton (along with several others) as war criminals for NATO's entire bombing campaign, saying the entire operation was in violation of the NATO charter.[citation needed]

Incident at Pristina airport

[edit]One of Clark's most controversial decisions during his SACEUR command was his attempted operation at Priština International Airport immediately after the end of the Kosovo War. Russian forces had arrived in Kosovo and were heading for the airport on June 12, 1999, two days after the bombing campaign ended, expecting to help police that section of Kosovo. Clark, on the other hand, had planned for the Kosovo Force to police the area. Clark called then-Secretary General of NATO, Javier Solana, and was told "of course you have to get to the airport" and "you have transfer of authority" in the area.

The British commander of the Kosovo Force, General Mike Jackson, however, refused to allow the British forces led by Captain James Blunt to block the Russians through military action saying "I'm not going to start the Third World War for you."[79][80][81] Jackson has said he refused to take action because he did not believe it was worth the risk of a military confrontation with the Russians, instead insisting that troops encircle the airfield. The stand-off lasted two weeks. Russian forces continued to occupy the airport, until eventually an agreement was secured for them to be integrated into peace-keeping duties, while remaining outside of NATO command.[81]

Jackson's refusal was criticized by some senior U.S. military personnel, with General Hugh Shelton calling it "troubling". During hearings in the United States Senate, Senator John Warner suggested that the refusal might have been illegal, and that if it was legal, rules potentially should be changed.[82] Still, British Chief of the Defence Staff Charles Guthrie agreed with Jackson.[83] Clark was subsequently ordered to step down from his position two months earlier than expected.[84] Jackson continued his career after the Pristina Incident: He was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (1998), received the Distinguished Service Order (1999), became Commander-in-Chief, Land Command (2000), and finally, in 2003, Chief of the General Staff, the highest position in the British Army.

Retirement

[edit]Clark received another call from General Shelton in July 1999 in which he was told that Secretary Cohen wanted Clark to leave his command in April 2000, less than three years after he assumed the post. Clark was surprised by this, because he believed SACEURs were expected to serve at least three years.[85] Clark was told that this was necessary because General Joseph Ralston was leaving his post as the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and would need another 4-star command within 60 days or he would be forced to retire. Ralston was not going to be appointed Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff due to an extramarital affair in his past, and the SACEUR position was said to be the last potential post for him.[86] Clark said this explanation "didn't wash"; he believed the legal issues did not necessarily bar him from a full term.[87] Clinton signed on to Ralston's reassignment, although David Halberstam wrote that the president and Madeleine Albright were angered at Clark's treatment. Clark spent the remainder of his time as SACEUR overseeing peacekeeper forces and, without a new command to take, was forced into retirement from the military on May 2, 2000.[88][89]

Rumors persisted that Clark was forced out due to his contentious relationship with some in Washington, D.C.; however, he has dismissed such rumors, calling it a "routine personnel action". The Department of Defense said it was merely a "general rotation of American senior ranks".[90] However, a NATO ambassador told the International Herald Tribune that Clark's dismissal seemed to be a "political thing from the United States".[91] General Shelton, working for the competing presidential campaign of John Edwards in 2003–2004,[92] said of Clark during his 2004 campaign that "the reason he came out of Europe early had to do with integrity and character issues, things that are very near and dear to my heart. I'm not going to say whether I'm a Republican or a Democrat. I'll just say Wes won't get my vote."[93] Shelton never elaborated further on what these issues were.[94]

Civilian career

[edit]Clark was chairman of the investment bank Rodman Renshaw, which filed for bankruptcy. The bank's questionable practices and Clark's direct role were detailed in the hit documentary film The China Hustle.[95] Clark began a public speaking tour in the summer of 2000 and approached several former government officials for advice on work after life in government, including House Speaker Newt Gingrich, White House Chief of Staff Mack McLarty, and Richard Holbrooke. Clark took McLarty's advice to move back to Little Rock, Arkansas, and took a position with Stephens Inc, an investment firm headquartered there. He took several other board positions at defense-related firms, and in March 2003 he amicably left Stephens Inc to found Wesley K. Clark & Associates. Clark wrote two books, Waging Modern War and Winning Modern Wars. He also authored forewords for a series of military biographies and a series of editorials.[1] In 2021 he published academic article Hybrid Warfare and the Challenge of Cyberattacks in The Challenge to NATO: Global Security and the Atlantic Alliance.[96]

Clark had amassed only about $3.1 million towards his $40 million goal by 2003, and he began considering running for public office instead of pursuing his business career.[97]

Clark is also a member of the Atlantic Council's board of directors.[98]

2004 presidential campaign

[edit]Clark has said that he began to truly define his politics only after his military retirement and the 2000 presidential election, won by George W. Bush. Clark had a conversation with Condoleezza Rice in which she told him that the war in Kosovo would not have occurred under Bush. Clark found such an admission unsettling, as he had been selected for the SACEUR position because he believed more in the interventionist policies of the Clinton administration. He said he would see it as a sign that things were "starting to go wrong" with American foreign policy under Bush.[99] Clark supported the administration's War in Afghanistan in response to the September 11, 2001, attacks but did not support the Iraq War.

Clark met with a group of wealthy New York Democrats including Alan Patricof to tell them he was considering running for the presidency in the 2004 election. Patricof, a supporter of Al Gore in 2000, met with all the Democratic candidates but supported Clark in 2004. Clark said that he voted for Al Gore and Ronald Reagan, held equal esteem for Dwight D. Eisenhower and Harry S. Truman, and was a registered independent voter throughout his military career. Clark stated that he decided he was a Democrat because "I was pro-affirmative action, I was pro-choice, I was pro-education ... I'm pro-health care ... I realized I was either going to be the loneliest Republican in America or I was going to be a happy Democrat."[100] Clark said he liked the Democratic party, which he saw as standing for "internationalism", "ordinary men and women", and "fair play".[101][102]

A "Draft Clark" campaign began to grow with the launch of DraftWesleyClark.com on April 10, 2003.[103] The organization signed up tens of thousands of volunteers, made 150 media appearances discussing Clark, and raised $1.5 million in pledges for his campaign. A different website, DraftClark2004.com, was the first organization to register as a political action committee in June 2003 to persuade Clark to run. They had presented him with 1000 emails in May 2003 from throughout the country asking him to run. One of DraftClark2004's founders, Brent Blackaby, said of the draft effort: "Just fifty-two years ago citizens from all over the country were successful in their efforts to draft General Eisenhower. We intend to do the same in 2004 by drafting General Clark. If he runs, he wins."[104][105]

In June 2003, Clark said that he was "seriously consider[ing]" running for president in an appearance on Meet the Press.[104] Clark announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential primary elections from Little Rock on September 17, 2003, months after the other candidates. He acknowledged the influence of the Draft Clark movement, saying they "took an inconceivable idea and made it conceivable".[106] The campaign raised $3.5 million in the first two weeks.[107][108] The internet campaign would also establish the Clark Community Network of blogs,[109] which remains in use and made heavy use of Meetup.com, where DraftWesleyClark.com had established the second-largest community of Meetups at the time.[110]

Clark's loyalty to the Democratic Party was questioned by some as soon as he entered the race. Senator Joe Lieberman called Clark's party choice a matter of "political convenience, not conviction". Republican governor Bill Owens of Colorado and University of Denver president Marc Holtzman have claimed Clark once said "I would have been a Republican if Karl Rove had returned my phone calls." Clark later claimed he was simply joking, but both Owens and Holtzman said the remark was delivered "very directly" and "wasn't a joke". Katharine Q. Seelye wrote that many believed Clark had chosen to be a Democrat in 2004 only because it was "the only party that did not have a nominee".[101] On May 11, 2001, Clark also delivered a speech to the Pulaski County Republican Party in Arkansas saying he was "very glad we've got the great team in office, men like Colin Powell, Don Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, Paul O'Neill—people I know very well—our president George W. Bush".[111] U.S. News & World Report ran a story two weeks later claiming Clark had considered a political run as a Republican.[112]

Clark, coming from a non-political background, had no position papers to define his agenda for the public. Once in the campaign, however, several volunteers established a network of connections with the media, and Clark began to explain his stances on a variety of issues. He was, as he had told The Washington Post in October, pro-choice and pro-affirmative action. He called for a repeal of recent Bush tax cuts for people earning more than $200,000 and suggested providing healthcare for the uninsured by altering the current system rather than transferring to a completely new universal health care system. He backed environmental causes such as promising to reverse "scaled down rules" the Bush administration had applied to the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts and dealing with the potential effects of global warming by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, livestock flatulence and other sources. Clark also proposed a global effort to strengthen American relations with other nations, reviewing the PATRIOT Act, and investing $100 billion in homeland security. Finally, he released a budget plan that claimed to save $2.35 trillion over ten years through a repeal of the Bush tax cuts, sharing the cost of the Iraq War with other nations, and cutting government waste.[113]

Some have speculated that Clark's inexperience at giving "soundbite" answers hurt him in the media during his primary campaign.[114] The day after he launched his campaign, for example, he was asked if he would have voted for the Iraq War Resolution, which granted President Bush the power to wage the Iraq War, a large issue in the 2004 campaign. Clark said, "At the time, I probably would have voted for it, but I think that's too simple a question," then "I don't know if I would have or not. I've said it both ways because when you get into this, what happens is you have to put yourself in a position—on balance, I probably would have voted for it." Finally, Clark's press secretary clarified his position as "you said you would have voted for the resolution as leverage for a UN-based solution." After this series of responses, although Clark opposed the war, The New York Times ran a story with the headline "Clark Says He Would Have Voted for War".[115] Clark was repeatedly portrayed as unsure on this critical issue by his opponents throughout the primary season. He was forced to continue to clarify his position and at the second primary debate he said, "I think it's really embarrassing that a group of candidates up here are working on changing the leadership in this country and can't get their own story straight ... I would have never voted for war. The war was an unnecessary war, it was an elective war, and it's been a huge strategic mistake for this country."[116]

Another media incident started during the New Hampshire primary September 27, 2003, when Clark was asked by Space Shuttle astronaut Jay C. Buckey what his vision for the space program was after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. Clark responded he was a great believer in the exploration of space but wanted a vision well beyond that of a new shuttle or space plane. "I would like to see mankind get off this planet. I'd like to know what's out there beyond the solar system." Clark thought such a vision could probably require a lifetime of research and development in various fields of science and technology. Then at the end of his remarks, Clark dropped a bombshell when he said "I still believe in E = mc². But I can't believe that in all of human history we'll never ever be able to go beyond the speed of light to reach where we want to go. I happen to believe that mankind can do it. I've argued with physicists about it. I've argued with best friends about it. I just have to believe it. It's my only faith-based initiative."[117] These comments prompted a series of derisive headlines, such as "Beam Us Up, General Clark" in The New York Times, "Clark is Light-Years Ahead of the Competition" in The Washington Post, "General Relativity (Retired)" on the U.S. News & World Report website, and "Clark Campaigns at Light Speed" in Wired magazine.[118][119]

Several polls from September to November 2003 showed Clark leading the Democratic field of candidates or as a close second to Howard Dean with the Gallup poll having him in first place in the presidential race at 20% as late as October 2003.[120] The John Edwards campaign brought on Hugh Shelton—the general who had said Clark was made to leave the SACEUR post early due to "integrity and character issues"—as an advisor, a move that drew criticism from the Clark campaign.[121] Since Dean consistently polled in the lead in the Iowa caucuses, Clark opted out of participating in the caucuses entirely to focus on later primaries instead. The 2004 Iowa caucuses marked a turning point in the campaign for the Democratic nomination, however, as front-runners Dean and Dick Gephardt garnered results far lower than expected, and John Kerry and John Edwards' campaigns benefited in Clark's absence. Clark performed reasonably well in later primaries, including a tie for third place with Edwards in the New Hampshire primary and a narrow victory in the Oklahoma primary over Edwards. However, he saw his third-place finishes in Tennessee and Virginia as signs that he had lost the South, a focus of his campaign. He withdrew from the race on February 11, 2004, and announced his endorsement of John Kerry at a rally in Madison, Wisconsin, on February 13.[122] Clark believed his opting out of the Iowa caucus was one of his campaign's biggest mistakes, saying to one supporter the day before he withdrew from the race that "everything would have been different if we had [been in Iowa]."[123]

Post-2004 campaign

[edit]Clark continued to speak in support of Kerry (and the eventual Kerry/Edwards ticket) throughout the remainder of the 2004 presidential campaign, including speaking at the 2004 Democratic National Convention on the final evening.[124] He founded a political action committee, WesPAC, in April 2004.[2] Fox News Channel announced in June 2005 that they had signed General Clark as a military and foreign affairs analyst.[125] He joined the Burkle Center for International Relations at UCLA as a senior fellow.[126] A managing partner of the companies that support the center, Ronald Burkle, described Clark's position as "illuminat[ing] the center's research" and "teaching [the] contemporary role of the United States in the international community".[127]

Clark campaigned heavily throughout the 2006 midterm election campaign, supporting numerous Democrats in a variety of federal, statewide,[3] and state legislature campaigns.[128] Ultimately his PAC aided 42 Democratic candidates who won their elections, including 25 who won seats formerly held by Republicans and 6 newly elected veteran members of the House and Senate.[129] Clark was the most-requested surrogate of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee throughout the 2006 campaign,[130] and sometimes appeared with the leadership of the Democratic Party when they commented on security issues.[131][132]

Clark has opposed taking military action against Iran and in January 2007 he criticized what he called "New York money people" pushing for a war. This led to accusations of antisemitism.[133]

In September 2007 Clark's memoir A Time to Lead: For Duty, Honor and Country. In the book Clark alleged that during a visit to the Pentagon in the autumn of 2001 after 9/11, a "senior general" told him that the Office of the Secretary of Defense had produced a confidential paper proposing a series of regime change operations in seven countries over a period of five years. He had made the allegation a number of times in public and media appearances in 2006 and 2007. The book also described a conversation Clark had with Paul Wolfowitz in May 1991 after the Gulf War, quoting Wolfowitz as lamenting the non-removal of Saddam Hussein, but also telling him that "...we did learn one thing that's very important. With the end of the Cold War, we can now use our military with impunity. The Soviets won't come in to block us. And we've got five, maybe 10, years to clean up these old Soviet surrogate regimes like Iraq and Syria before the next superpower emerges to challenge us...".[134]

Clark serves on the Advisory Boards of the Global Panel Foundation and the National Security Network. He is also the chairman of Enverra,[135] and was also chairman of Rodman & Renshaw, a New York investment bank,[136] and Growth Energy.[137] His chairmanship at Rodman & Renshaw is part of the documentary The China Hustle. Clark is interviewed about his involvement in selling toxic stocks of unregulated Chinese companies; eventually though, he exits the interview to avoid association with Rodman & Renshaw, which went bankrupt in 2013.[138] The film speculates that the company used his name as chairman to gain legitimacy for its operations.[139]

Tiversa

[edit]In July 2007, Clark testified before the United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability about the discovery of classified information on file-sharing networks by the cybersecurity firm Tiversa, where he served on the board of advisers.[140][141][142]

Speculation of 2008 presidential campaign

[edit]Clark was mentioned as a potential 2008 presidential candidate on the Democratic ticket before endorsing Hillary Clinton for president.[143] Before that time, he was ranked within the top Democratic candidates according to some Internet polls.[144][145] After endorsing Hillary Clinton, Clark campaigned for her in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and Ohio and in campaign commercials. There are many reports that Clinton had already decided to choose Clark to be her running mate had she won the nomination. The Clinton campaign even considered picking Clark as a running mate with the team running together in the primaries, though the idea was later abandoned.[146] After Barack Obama secured the Democratic nomination, Clark voiced his support for Obama.[5] Clark was considered to be one of Obama's possible vice-presidential running mates. Clark, however, publicly endorsed Kansas governor Kathleen Sebelius for the position, introducing her as "the next Vice President of the United States" at a June 2008 fundraiser in Texas.[147] Obama eventually chose Joe Biden as his running mate.[148]

McCain military service controversy

[edit]On June 29, 2008, Clark made comments on Face the Nation that were critical of Republican John McCain, calling into question the notion that McCain's military service alone had given him experience relevant to being president. "I certainly honor [McCain's] service as a prisoner of war", Clark said, "but he hasn't held executive responsibility. That large squadron in the Navy that he commanded—it wasn't a wartime squadron. He hasn't been in there and ordered the bombs to fall."[149] When moderator Bob Schieffer noted that Obama had no military experience to prepare him for the presidency nor had he "ridden in a fighter plane and gotten shot down", Clark responded that, ultimately, Obama had not based his presidential bid on his military experience, as McCain has done throughout his campaign. Clark's retort, however, is what drew rebuke. In referring to McCain's military experience, he stated: "Well, I don't think riding in a fighter plane and getting shot down is a qualification to be president."[150] Both the McCain and Obama campaigns subsequently released statements rejecting Clark's comment. However, Clark has received the backing of several prominent liberal groups such as MoveOn.org and military veteran groups such as VoteVets.org; Obama ultimately stated that Clark's comments were "inartful" and were not intended to attack McCain's military service.[151] In the days following the controversial interview, Clark went on several news programs to reiterate his true admiration and heartfelt support for McCain's military service as a fellow veteran who had been wounded in combat.[152][153] In each program, Clark reminded the commentator and the viewing public that while he honored McCain's service, he had serious concerns about McCain's judgment in matters of national security policy, calling McCain "untested and untried".[154]

Book on modern wars

[edit]In Clark's book Winning Modern Wars, published in 2003, he describes his conversation with a military officer in the Pentagon shortly after 9/11 regarding a plan to attack seven countries in five years: "As I went back through the Pentagon in November 2001, one of the senior military staff officers had time for a chat. Yes, we were still on track for going against Iraq, he said. But there was more. This was being discussed as part of a five-year campaign plan, he said, and there were a total of seven countries, beginning with Iraq, then Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and finishing off Iran."[155][156][157] Clark regards the 2003 invasion of Iraq as "a huge mistake".[158]

Paradise Papers

[edit]On November 5, 2017, the Paradise Papers, a set of confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investment, revealed that online gambling company The Stars Group, then Amaya, along with its former member of board of directors Wesley Clark, did business with offshore law firm Appleby.[159][160]

Reality television career

[edit]Clark was the host of Stars Earn Stripes, a reality television program that aired on NBC for four episodes in 2012. The program followed celebrities who competed in challenges based on U.S. military exercises.

Awards and honors

[edit]Wesley Clark has been awarded numerous honors, awards, and knighthoods over the course of his military and civilian career. Notable military awards include the Defense Distinguished Service Medal with four oak leaf clusters, the Legion of Merit with three oak leaf clusters, the Silver Star, and the Bronze Star with an oak leaf cluster.[161] Internationally Clark has received numerous civilian honors such as the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and military honors such as the Grand Cross of the Medal of Military Merit from Portugal and knighthoods.[162] Clark has been awarded some honors as a civilian, such as the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John Shalikashvili, in 1998,[163] and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2000.[164] The people of Gjakova, Kosovo, named a street after him for his role in helping their city and country.[165][166] The city of Madison in Alabama has also named a boulevard after Clark.[167][168] Municipal approval has been granted for the construction of a new street to be named "General Clark Court" in Virginia Beach, Virginia.[169] He has also been appointed a Fellow at the Burkle Center for International Relations at UCLA. He is a member of the guiding coalition of the Project on National Security Reform. In 2000 he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.[170] In 2013, General Clark was awarded the Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award jointly presented by the Prague Society for International Cooperation and Global Panel Foundation .[171]

Bibliography

[edit]- Don't Wait for the Next War: A Strategy for American Growth and Global Leadership. New York: PublicAffairs. 2014. ISBN 978-1-61039-433-8.

- A Time to Lead: For Duty, Honor and Country. St Martin's Press. 2007. ISBN 978-1403984746.

- Great Generals series. Palgrave Macmillan. 2006. (foreword)

- Winning Modern Wars: Iraq, Terrorism, and the American Empire. New York: PublicAffairs. 2004. ISBN 1-58648-277-7.

- Waging Modern War: Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Future of Combat. New York: PublicAffairs. 2001. ISBN 1-58648-043-X.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "WesPAC – Securing America". Archived from the original on September 22, 2006. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ a b "WesPAC History". Archived from the original on November 4, 2006. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ a b "List of all endorsed candidates". Securing America. Archived from the original on November 4, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Fouhy, Beth (September 16, 2007). "Wesley Clark Endorses Hillary Clinton". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Clark, Wesley (June 6, 2008). "Unite Behind Barack Obama". Securing America. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ "Enverra - Always Invested". Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Press statements by PM Victor Ponta and General Wesley K. Clark appointed as Special Adviser to Prime Minister on security and economic strategy matters, at the end of the Executive meeting Archived October 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Retired US General Wesley Clark becomes an adviser to Romania's PM Victor Ponta". Romania-Insider.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Felix, Antonia (May 19, 2004). Wesley K. Clark: A Biography. HarperCollins. ISBN 9781557046253.

- ^ Felix, Antonia, Wesley Clark: A Biography. Newmarket Press; New York, 2004. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, held at Chicago, Illinois, June 27 to July 2, inclusive, 1932

- ^ Felix, pp. 12–3.

- ^ "Clark 2004 biography". Clark04.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d American Son Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine by Linda Bloodworth. Produced by Linda Burstyn, Cathee Weiss and Douglas Jackson; edited by Gregg Featherman.

- ^ "Nominations Before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Second Session, 103d Congress: Hearings Before the Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate". Vol. 103, no. 873. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1994. pp. 477–479. ISBN 9780160463860.

- ^ Felix, pp. 14–5.

- ^ Felix, p. 22.

- ^ Felix, p. 25.

- ^ Felix pp. 16–7.

- ^ Felix, p. 21.

- ^ Felix, p. 41.

- ^ Felix, p. 52.

- ^ Felix, p. 49.

- ^ Lambert, J. C., MajGen. "Letter of Acceptance to West Point Military Academy." Letter to Wesley J. Clark. April 24, 1962.

- ^ a b Felix, pp. 54–68.

- ^ Felix, pp. 69–80.

- ^ Felix, pp. 80–4.

- ^ Felix, pp. 85–7.

- ^ Felix, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f Detailed resume included with his nomination before the Senate Armed Services Committee, First Session, 105th Congress. July 9, 1997.

- ^ Felix, pp. 88–95.

- ^ Felix, pp. 95–7.

- ^ "White House Assigns Fellow to OMB Office," Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 29, 1975.

- ^ Felix, p. 105. "The commander at Fort Carson, Gen. John Hudachek, had a well-known aversion to West Point cadets and fast-risers like Clark. Even though Clark made quick and outstanding progress with the armor unit, Hudachek expressed his attitude towards Clark by omitting him from a list of battalion commanders selected to greet a congressional delegation visiting the base." Colin Powell also ran afoul of Maj. Gen. Hudachek—see Colin Powell, My American Journey.

- ^ War in a Time of Peace: Bush, Clinton, and the Generals, by David Halberstam, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001, pp. 432–33.

- ^ Felix, pp. 102–10.

- ^ Felix, pp. 97–102.

- ^ Felix, pp. 110–16.

- ^ "Digitization: Key to Landpower Dominance," by Wesley Clark for Army magazine, November 1993.

- ^ Felix, pp. 116–20.

- ^ Felix, p. 122

- ^ Felix, pp. 120–22.

- ^ "CEO". Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Felix, p. 131

- ^ a b Clark, Waging, p. 68.

- ^ Felix, pp. 131–34.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 38

- ^ Clark's Military Record Archived August 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine by KATHARINE Q. SEELYE and ERIC SCHMITT for The New York Times on September 20, 2003. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ a b Nominations before the Senate Armed Services Committee, First Session, 105th Congress. July 9, 1997.

- ^ Felix, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 40.

- ^ The Trouble with Wes by Robert Novak on Townhall.com on September 22, 2003. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ To End a War by Richard Holbrooke, New York: Random House, 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Felix, pp. 126–29

- ^ "Wesley K. Clark, A Candidate in the Making, Part 2: An Arkansas Alliance and High-Ranking Foes" by Michael Kranish for Boston Globe on November 17, 2003.

- ^ Nomination: PN382-105 on July 9, 1997. Retrieved December 14, 2006 from Thomas.gov Archived September 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Felix, p. 137.

- ^ "Interview with Wesley Clark for PBS Frontline". PBS. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Felix, pp. 138–40.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 342.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 269.

- ^ Consulate General of the United States Hong Kong & Macau (August 2, 1999). "Statements on NATO Bombing of China's Embassy in Belgrade". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on October 13, 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 273.

- ^ Felix, pp. 140–43.

- ^ "No justice for the victims of NATO bombings". Amnesty International. April 23, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (January 19, 2015). "Chomsky: Paris attacks show hypocrisy of West's outrage". CNN.

- ^ "Nato challenged over Belgrade bombing". BBC News. October 24, 2001.

- ^ "U.S. Media Overlook Expose on Chinese Embassy Bombing". Fair.org. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Tenet, George (July 22, 1999). "DCI Statement on the Belgrade Chinese Embassy Bombing House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence Open Hearing". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ Clark, Waging, pp. 296–97.

- ^ "Press Briefing by Javier Solana". Nato.int. June 10, 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Resolution 1244 adopted by the United Nations Security Council on June 10, 1999.

- ^ The Impact of the Laws of War in Contemporary Conflicts (PDF) by Adam Roberts on April 10, 2003 at a seminar at Princeton University titled "The Emerging International System – Actors, Interactions, Perceptions, Security". Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ "Two die in Apache crash". BBC News. May 5, 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, Final Report to the Prosecutor by the Committee Established to Review the NATO Bombing Campaign Against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, para. 53. Available on the ICTY website. Also published in 39 International Legal Materials 1257–83 (2000).

- ^ "Ubijeno više od 2.000 civila, više od 5.000 ranjeno". Glas Javnosti (in Serbian). June 10, 1999. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign by Human Rights Watch in February 2000. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ Felix, p. 152.

- ^ Grice, Elizabeth (September 1, 2007). "General Sir Mike Jackson speaks out". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "James Blunt, General Sir Mike Jackson; Nov 14, 10", BBC "Pienaar's Politics" (long audio file)

- ^ a b "How James Blunt saved us from World War 3". The Independent. November 15, 2010.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (September 10, 1999). "U.S. General Was Overruled in Kosovo". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Online Newshour: Waging Modern War Archived November 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine interview by Margaret Warner for PBS on June 15, 2001. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ Tran, Mark (August 2, 1999). ""I'm not going to start Third World War for you," Jackson told Clark". The Guardian. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 408.

- ^ Ralston withdraws name from consideration by Wolf Blitzer and Carl Rochelle on June 9, 1997. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Clark, Waging, p. 409.

- ^ Ralston's bio Archived September 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine from the NATO website. Last updated January 20, 2003. When Ralston is listed as taking the USEUCOM position (May 2, 2000) Clark no longer has a command.

- ^ Felix, pp. 147–50.

- ^ "Nato commander denies snub". BBC News. July 29, 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ General's Early Exit Upsets NATO by Joseph Fitchett for the International Herald Tribune on July 29, 1999. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ Arkin, William (December 7, 2003). "The General Unease With Wesley Clark". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Gen. Shelton shocks Celebrity Forum, says he won't support Clark for president Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine by Joan Garvin on September 24, 2003. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ Felix, p. 202.

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (March 29, 2018). "Review: 'The China Hustle' Warns of Dicey Investments". The New York Times.

- ^ Clark, Westley (2021). "Hybrid Warfare and the Challenge of Cyberattacks". In Michael O. Slobodchikoff; G. Doug Davis; Brandon Stewart (eds.). The challenge to NATO: Global security and the Atlantic alliance. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-64012-498-1. OCLC 1266643958.

- ^ Felix, pp. 154–73.

- ^ "Board of Directors". Atlantic Council. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "The Last Word: Wesley Clark". August 7, 2003. Archived from the original on August 7, 2003. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "In His Own Words". The Washington Post, October 19, 2003.

- ^ a b "To Find Party, General Marched to His Own Drummer," The New York Times, October 5, 2003.

- ^ Felix, pp. 190–91.

- ^ "Clark bio". Archived from the original on December 5, 2003. Retrieved May 12, 2017. from his 2004 campaign site and Clark for President. Clark For President – P.O. Box 2959, Little Rock, AR 72203. This version is from the Internet Archive on December 5, 2003.

- ^ a b "Draft Clark 2004 for President Committee Files with FEC," US Newswire, June 18, 2003.

- ^ Felix, pp. 191–13.

- ^ "Clark's Announcement speech in Little Rock". Archived from the original on October 8, 2003. Retrieved May 12, 2017. by Wesley K. Clark hosted on Clark04 on September 17, 2003. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ "Wesley Clark Raises More than $3.5M in Fortnight," Forbes, October 6, 2003.

- ^ Felix, pp. 196–97.

- ^ The Clark Community Network. "Here is the video link of Gen. Clark on MSNBC today". Securing America. Archived from the original on January 12, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Case Studies: Draft Wesley Clark". Grassroots.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Was Wesley Clark a Republican?". Factcheck.org. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ The Chameleon Candidate by Doug Ireland for the LA Weekly on September 25, 2003. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ Felix, pp. 197–99.

- ^ Wesley Clark: Mending our torn country into a nation again by Jerseycoa on the DemocraticUnderground on January 19, 2004. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- ^ "Clark Says He Would Have Voted for War," The New York Times, September 19, 2003.

- ^ "Clark Under Sharp Attack in Democratic Debate," The Washington Post, October 10, 2003.

- ^ "transcript of remarks".

- ^ Felix, pp. 174–75.

- ^ Clark Campaigns at Light Speed Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine by Brian McWilliams on September 30, 2003. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- ^ "Cain Surges, Nearly Ties Romney for Lead in GOP Preferences". Gallup.com. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ Clark Communications Director questions John Edwards retaining Hugh Shelton by Matt Bennett, hosted on Clark04.com on November 11, 2003. Retrieved February 2, 2007. Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wes Clark Endorses John Kerry by Wesley Clark on February 13, 2004. Retrieved November 2, 2006. Archived December 21, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Felix, pp. 203–06.

- ^ Video of Clark's speech from The Washington Post website on July 29, 2004. Retrieved January 31, 2007. Full schedule can be seen here.

- ^ Gen. Wesley Clark Joins FNC as Foreign Affairs Analyst Archived April 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine from TVWeek by Michele Greppi on June 15, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ "UCLA Burkle Center for International Relations". Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- ^ Gen. Wesley Clark to Join UCLA Burkle Center for UCLA News by Judy Lin on September 16, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ All Endorsed State/Local candidates Archived March 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Time to Lead Archived February 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Clark considering presidential bid Archived January 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine by the Arkansas Times Staff for the Arkansas Times on November 19, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Democrats – Joined by General Wesley Clark – Release New Report on Bush National Security Failures Archived November 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Democratic Leadership Call for a New Direction on Security Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Top Dem Wesley Clark Says: 'N.Y. Money People' Pushing War With Iran". Archived from the original on January 14, 2007.

- ^ Conason, Joe (October 12, 2007). "Seven countries in five years". Salon. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Wesley Clark's LinkedIn profile. [1]. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Rodman & Renshaw (2009). Board of Directors. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ "General Wesley Clark Announced as Growth Energy Co-Chairman". Growth Energy. February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ Direct Markets Holdings Files to Liquidate. Retrieved May 4, 2022. [2]

- ^ "The China Hustle Unveils the Biggest Financial Scandal You've Never Heard Of". Vanity Fair. March 28, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "Advisors". Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Rugaber, Christopher (July 24, 2007). "House panel scrutinizes threats of file-sharing". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021.

"The American people would be totally outraged if they were aware of what is inadvertently shared ... by government agencies," said retired Gen. Wesley Clark, who is on the advisory board of Tiversa Inc., a data security company. Clark did not name the defense contractors whose computing passwords were compromised.

- ^ Katchadourian, Raffa (October 28, 2019). "A Cybersecurity Firm's Sharp Rise and Stunning Collapse". The New Yorker.

In 2006, a more significant investor signed on: Adams Capital Management, named for its founder Joel Adams, a Pittsburgh venture capitalist. [...] Adams Capital invested more than four million in Tiversa, and helped secure an all-star board of advisers. Maynard Webb, the former eBay executive and chairman of Yahoo!, joined, and he brought on other executives from Silicon Valley. Howard Schmidt became an adviser, and soon afterward was appointed the cybersecurity czar for the Obama Administration. General Wesley Clark, the former Supreme Allied Commander of nato, came on, and developed a good rapport with Boback, who sold his practice to devote himself to Tiversa full time.

- ^ "Retired 4-star endorses Clinton for president – Army News, opinions, editorials, news from Iraq, photos, reports". Army Times. September 16, 2007. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Web Poll results Archived August 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine from ChooseOurPresident2008 by Alex Christensen. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ^ 2008 straw poll by kos for DailyKos on January 16, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (November 19, 2007). "Clinton and Clark Campaign in Iowa".

- ^ "Clark touts Sebelius as VP | Wichita Eagle Blogs". Blogs.kansas.com. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Obama introduces Biden as running mate". CNN. August 23, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "TPMtv: Wesley Clark Hyperventorama". July 1, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009 – via YouTube.

- ^ ""Attacking" McCain's Military Record". CJR. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Retrieved July 7, 2008". Politico. July 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Retrieved July 8, 2008". CNN. November 16, 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Retrieved July 8, 2008". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Retrieved July 8, 2008". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Wesley Clark, Winning Modern Wars (New York: Public Affairs, 2003), 130.

- ^ Steven, David. "The full, crazy plan". Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ ""Seven countries in five years"". Salon. October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Wesley (August 10, 2017). "The US has only one option on North Korea's nuclear threat now". CNBC News. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "Wesley K. Clark". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. November 2017.

- ^ "Trump's cabinet members amongst those named in Paradise Papers Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Daily Balochistan Express. November 6, 2017.

- ^ U.S. Military decorations Archived November 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ International honors Archived July 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Civilian honors Archived July 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "4th image down from". Awesclarkdemocrat.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Former NATO commander, retired Gen. Wesley Clark to visit Kosovo". Kosovareport.blogspot.com. May 24, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Google search results containing real estate listings for Wesley Clark Blvd in Madison, Alabama.

- ^ Transcript of Countdown with Keith Olbermann show on NBC News where he mentions road named after Clark in Alabama.

- ^ Announcement by architect upon completion of negotiations granting municipal approval for construction of "General Clark Court" in Northern Village subsection in Virginia Beach area of the state of Virginia. Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Library, CNN. "Wesley Clark Fast Facts". CNN. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "List of Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award Winners". Prague Society. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Felix, Antonia (2004). Wesley K. Clark: A Biography. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-625-5.

External links

[edit]- Draft Clark for President (archive only)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Wesley Clark Issue positions and quotes

- Wesley Clark collected news stories and commentary

- Wesley Clark Speaks About His New Memoir, War, and the Upcoming Election

- Video: Wesley Clark discusses Asia Society Task Force Report on US Policy in Burma at the Asia Society, New York, April 7, 2010

- Wesley Clark at IMDb

- 1944 births

- Living people

- Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford

- American chief executives

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- American people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- American people of English descent

- American political writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American Rhodes Scholars

- Arkansas Democrats

- Atlantic Council

- Commanders with Star of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Baptist denominations

- Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Grand Officers of the Military Order of Savoy

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- National War College alumni

- NATO Supreme Allied Commanders

- Officers of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

- Officers of the Ordre national du Mérite

- Order of Duke Trpimir recipients

- People from West Point, New York

- Military personnel from Chicago

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Defense Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Meritorious Service Decoration

- Recipients of the Military Order of the Cross of the Eagle, Class I

- Recipients of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- United States Army generals

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Candidates in the 2004 United States presidential election

- 21st-century American politicians

- White House Fellows

- Writers from Chicago

- Catholics from New York (state)

- Catholics from Illinois

- Hall High School (Arkansas) alumni

- Recipients of the Meritorious Service Medal (United States)

- People named in the Paradise Papers