Nordhausen, Thuringia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

Nordhausen | |

|---|---|

View of Nordhausen (city centre) | |

Location of Nordhausen within Nordhausen district  | |

| Coordinates: 51°30′18″N 10°47′28″E / 51.50500°N 10.79111°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Thuringia |

| District | Nordhausen |

| Subdivisions | 12 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2017–23) | Kai Buchmann[1] (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 110.86 km2 (42.80 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 185 m (607 ft) |

| Population (2022-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 41,339 |

| • Density | 370/km2 (970/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 99734 |

| Dialling codes | 03631 |

| Vehicle registration | NDH |

| Website | www.nordhausen.de |

Nordhausen (pronounced [ˈnɔʁtˌhaʊ̯zn̩] ) is a city in Thuringia, Germany. It is the capital of the Nordhausen district and the urban centre of northern Thuringia and the southern Harz region; its population is 42,000. Nordhausen is located approximately 60 km (37 miles) north of Erfurt, 80 km (50 miles) west of Halle, 85 km (53 miles) south of Braunschweig and 60 km (37 miles) east of Göttingen.

Nordhausen was first mentioned in records in the year 927 and became one of the most important cities in central Germany during the later Middle Ages. The city is situated on the Zorge river, a tributary of the Helme within the fertile region of Goldene Aue (golden floodplain) at the southern edge of the Harz mountains. In the early 13th century, it became a free imperial city, so that it was an independent and republican self-ruled member of the Holy Roman Empire. Due to its long-distance trade, Nordhausen was prosperous and influential, with a population of 8,000 around 1500. It was the third-largest city in Thuringia after Erfurt, today's capital, and Mühlhausen, the other free imperial city in the land.

Nordhausen was once known for its tobacco industry and is still known for its distilled spirit, Nordhäuser Doppelkorn. Industrialization accompanied railway construction that linked the cities to major markets in the mid-19th century. In the late 19th century, narrow-gauge railways were constructed in this region through the Harz mountains. In December 1898 the Nordhausen-Wernigerode Railway Company (Nordhausen-Wernigeroder Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft) or NWE added a line, with the full network operating by 1899. The Harz Narrow Gauge Railways are maintained today by local authorities and frequented primarily by tourists.

In the early 20th century, this became a centre of the engineering and arms industries. During World War II, the Nazi German government established and operated the nearby KZ Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, where 60,000 forced labourers had to work in the arms industry. They were prisoners of war and persons from occupied territories. Some 20,000 persons died because of the bad conditions. In April 1945, most of the city was destroyed by Royal Air Force bombings, resulting in 8,800 casualties (more than 20% of the population). Most of the historic buildings in the city were destroyed; it suffered the most damage during the war of any city in Thuringia. A week later the United States troops occupied the city, followed weeks later by the Soviet Red Army. The city was within the Soviet zone of occupation, and later the territory was known as East Germany. Hundreds of German scientists and their families from Nordhausen were among thousands deported to the Soviet Union after the war to work on advanced rocket and other arms engineering projects.

Nordhausen is the birthplace of the mathematician Oswald Teichmüller, known for his groundbreaking work on the Teichmüller spaces – which were named after him. It is the site of the Nordhausen University of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschule Nordhausen), founded in 1997 after the reunification of Germany. The university has 2,500 students.

History

Imperial City of Nordhausen Reichstadt Nordhausen | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1220–1802 | |||||||||

Nordhausen in the 17th century | |||||||||

| Status | Imperial city | ||||||||

| Capital | Nordhausen | ||||||||

| Government | Imperial city | ||||||||

| Historical era | High Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Settlement founded | 650-700 | ||||||||

| 27 July 1220 | |||||||||

• Reichsfreiheit confirmed | 1290 | ||||||||

• New city constitution | 14 February 1375 | ||||||||

• Joined Hanseatic League | 1430 | ||||||||

| 1523 | |||||||||

| 1802 | |||||||||

• Ceded to Westphalia | 1807–13 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Middle Ages

The Franks colonized the area around Nordhausen about 800, many place names here have a Frankish origin, discernible by the suffix -hausen (like Nordhausen itself, Sundhausen, Windehausen and the later abandoned settlement Stockhausen as well as the neighbouring cities of Mühlhausen, Sondershausen, Frankenhausen and Sangerhausen). Nordhausen itself is first mentioned in a 13 May 927 document of King Henry the Fowler. He built a castle here, which is traceable between 910 and 1277 and became a centre of the empire during the 10th century. Gerberga of Saxony, Henry's daughter is supposed to have been born there, as was Henry I, Duke of Bavaria. The first market was established in the 10th century, as was a chapter of nuns (961). During the 12th century, the old town was semi-planned and established around the new market place and St. Nicholas' Church.

Nordhausen was Reichsgut (estate of the German emperor) from the beginning, but in 1158, Frederick Barbarossa donated it to the local chapter of nuns, which was converted to a cathedral chapter by Frederick II in 1220, whereby the city came back to the empire and became an Imperial Free City. Nordhausen was granted the privileges of a town around 1200, in 1198 it was first mentioned as a villa and in 1206, there was a mayor, a Vogt and citizens. The municipal law of Nordhausen was similar to that of Mühlhausen, hence the Mühlhausen Book of Law was adopted in the mid-13th century. Today's city wall was established between 1290 and 1330 and cut the old town off from Altendorf in the north-west, the new town in the west and Altnordhausen in the south. Nevertheless, the new town was legally incorporated in 1365. Besides the parish churches, many monasteries were founded during the late Middle Ages in Nordhausen (Cistercians in Altnordhausen (Frauenberg, about 1200) and Altendorf (1294), Augustines where the Nordhäuser distillery is today (1312), Franciscans at Georgengasse (1230) and Dominicans at Predigerstraße (1287)). As distinct from Mühlhausen and many other free imperial cities, Nordhausen did not own any territories or villages in the surrounding area.

The city's independence was endangered by the ambitions of regional counts, especially by those of Hohnstein County (based in near Ilfeld), who extorted funds from Nordhausen during the 14th century. On the other hand, the debts of the Hohnstein Counts were gigantic: they owed 86 citizens of Nordhausen 5744 Mark silver in 1370. In 1306, Nordhausen allied with the two other major Thuringian cities Erfurt and Mühlhausen against the Wettins and the local counts (Hohnstein, Stolberg, Schwarzburg, Beichlingen etc.) and joined the Hanseatic League together with them in 1430. Further alliances were concluded with Goslar, Halberstadt, Quedlinburg and Aschersleben to represent urban interests against the landlords.

In 1349, during a plague epidemic, some number of Jewish residents were killed by the citizenry with support from Frederick II, Margrave of Meissen. According to legend, they danced on their way to the pyre.[3][4]

Early modern period

In 1500 it became part of the Lower Saxon Circle, and from around the same year the city began producing fermented grain liquor, which became famous under the name Nordhäuser Doppelkorn. In 1523, a year in which Thomas Müntzer spent some time in the city, the Protestant Reformation came to Nordhausen, which was one of the first cities that adopted the new doctrine. The cathedral chapter stayed catholic, protected by the Habsburg emperors but the other monasteries got closed during the following decades and their heritage came to the city. During the 16th century, Nordhausen succeeded to push back the influence of the Wettins and the Hohnstein counts by buying back their privileges over the city. This marked the peak in pre-modern urban development, followed by some centuries of decline introduced by the Thirty Years' War. In 1551, the Jews were expelled from the city. They were not generally permitted to live there again until 1807.[3][4]

After the war, the Electorate of Brandenburg tried to incorporate the free cities of Nordhausen, Mühlhausen and Goslar, because it already became large territories in the Harz region. The Electorate of Saxony, protecting power of Nordhausen gave hidden support to the Brandenburgs, so that Nordhausen tried to keep its independence through the protection by the Hanovers. After the Brandenburg-Prussians had occupied Nordhausen between 1703 and 1714, the city got protection of Hanover resp. England, which paid 50,000 Talers to the Prussians to leave Nordhausen, which was moreover destroyed by two town fires in 1710 and 1712. Under the protection of Hanover, the economy improved again and the production of tobacco since mid-18th century brought new wealth to Nordhausen.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Prussian troops occupied Nordhausen on 2 August 1802; the city lost its status as an Imperial Free City during the German Mediatisation. After Prussia's defeat against Napoleon, it became part of the Kingdom of Westphalia created in 1807.

Since 1815

Following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, Nordhausen was included in the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of Saxony created in 1816. During the mid-19th century, industrialisation started in Nordhausen with production of chewing tobacco, alcoholic beverages, paper and textiles. The breakthrough was reached as Nordhausen got connected to main railways in four directions between 1866 and 1869. In 1882 it became an urban district (until 1950). In the late 19th century, narrow-gauge railways were constructed linking Nordhausen and other cities through the Harz mountains, operating by 1899.

As the engineering industry developed after 1900, the city saw an economic heyday. Industry developed and expanded during the following decades.

1900 to present

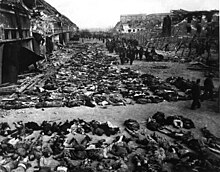

In the 1930s the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. It imposed discrimination against Jews, with increasing restrictions and violence such as Kristallnacht in 1938, when businesses and synagogues were destroyed. It deported Jews to concentration and death camps. The Mittelbau-Dora Nazi concentration camp, established in 1943 after the destruction of Peenemünde, was located on the outskirts of Nordhausen during World War II to provide labor for the Mittelwerk V-2 rocket factory in the Kohnstein. Over its period of operation, around 60,000 inmates passed through Dora and its system of subcamps, of whom around 20,000 died from bad working conditions, starvation, and diseases, or were murdered. Around 10,000 forced labourers were deployed in several factories within the city; up to 6,000 of them were interned at Boelcke Kaserne, working for a Junkers factory.

On August 24, 1944, 11 B-17 Flying Fortresses of Mission 568 bombed the airfield at Nordhausen as a target of opportunity.[5] From January 1945, sick and dying prisoners were interned at Boelcke Kaserne. On April 3 and 4, 1945 three-quarters of Nordhausen was destroyed by bombing raids of the Royal Air Force, resulting in the deaths of around 8,800 people, including 1,300-1,500 sick prisoners at the Boelcke Kaserne barracks within Nordhausen.[6]

On 11 April 1945, United States troops occupied the town, and on 2 July the Red Army of the Soviet Union took over. A Special Mission V-2: US operation was undertaken by Maj. William Bromley, intended to recover V-2 rocket parts and equipment. Maj. James P. Hamill co-ordinated the rail transport of said equipment with the 144th Motor Vehicle Assembly Company, from Nordhausen to Erfurt (Operation Paperclip).

On 18 July the Soviet administration created the Institute Rabe to develop Soviet rocket technology on the basis of the substantially more sophisticated V-2 rockets. In May 1946 the Institute was subsumed into the new Institute Nordhausen, under an expanded programme of research across the Soviet occupation zone, including a new Institute Berlin. On 22 October 1946, under Operation Osoaviakhim, 10–15,000 German scientists, engineers and their families were deported to the Soviet Union, including around 300 from Nordhausen.[7] Transplanted along with their equipment, many of the scientists and their families lived there until the early 1950s.

Nordhausen became part of East Germany in 1949. It was administered within Bezirk Erfurt since 1952. The reconstruction of Nordhausen took a long time during the 1950s and 1960s and was carried out in modern architectural style. Town hall, the cathedral and St. Blaise's Church were the only rebuilt historic monuments. The Uprising of 1953 in East Germany found a centre in Nordhausen, because the living conditions within the destroyed city were still bad, and the people were exceedingly dissatisfied. Only the Soviet army could defeat the uprising. Within the GDR, Nordhausen was the centre of tobacco and liqueur production.

After the German reunification of 1990, Nordhausen was made part of the recreated state of Thuringia. The 1990s brought an economic crisis with high unemployment rates, and many uncompetitive communist-era factories had to close. Nevertheless, the local industry revived after the crisis. Since 2000 the economy is growing again, with the unemployment rate decreasing and Nordhausen consolidated as the urban centre of northern Thuringia. The Nordhausen University of Applied Sciences was founded in 1997, attracting students to the town. The Landesgartenschau (Land's horticultural exhibition) in 2004 was an impetus to further urban development.

Geography and demographics

Topography

Nordhausen is situated at the border between the flat and fertile area of Goldene Aue in the south and the foothills of the Harz mountains in the north on a level of approx. 180 m of elevation. The Zorge river crosses the city from northwest to southeast and the bigger Helme river runs in west-eastern direction at the southern border of the municipality. Between them are some quarry ponds of former gravel mining near the Sundhausen and Bielen districts. To the north, the terrain is getting more hilly and part of a karst area south to the Harz mountains. The north-west of the territory is marked by the Kohnstein hill (335 m) and the north-east is the Rüdigsdorf Switzerland, a small area with a beautiful landscape up to 350 m of elevation around Rüdigsdorf district. South of Helme river, the terrain gets also hilly around the Windleite mountains between Nordhausen and Sondershausen. Most of the municipal territory is in agricultural use. The forests are located first between the city centre in the south and Rüdigsdorf in the north (with interruptions), second at Kohnstein hill and third in the east around Rodishain and Stempeda.

Administrative division

Nordhausen abuts the following municipalities: Ellrich, Harztor, Harzungen, Neustadt, Buchholz and Herrmannsacker in the north, Südharz and Urbach in the east, Heringen and Kleinfurra in the south and Werther in the west. Except of Südharz, which is part of Mansfeld-Südharz district in Saxony-Anhalt, all the neighbouring municipalities belong to the Nordhausen district in Thuringia.

The following villages belong to the Nordhausen municipality:

|

|

Demographics

Nordhausen had approx. 8,000 inhabitants during the late Middle Ages around 1500, which was the third-largest number within today's Thuringia, after Erfurt, the current capital and Mühlhausen. The early modern period brought stagnation to the city, so that the population was also 8,000 around 1800. Nordhausen fell back behind the new ducal residence cities like Weimar, Gotha or Altenburg in this ages and lost its former importance. Nevertheless, Industrialization started in the 1860s, as Nordhausen got connected to the railway and the population grew to 26,000 and 33,000 in 1910, which was a smaller growth than in other cities of comparable size during that period of rapid urbanisation in Germany. Until 1940, the population rose to 42,000, but decreased due to the destruction of the city in World War II to 32,000 in 1946. The old level was attained again in the early 1960s and the population peak was reached in 1988 with 48,000. The bad economic situation after the German reunification led to emigration during the 1990s and the population shrunk in that decade. Because of the various incorporations of neighbouring villages, the amount looks smaller than it was.

The average change of population within the last years (2009–2012) was approximately -0.35% p. a, whereas the population in bordering rural regions is shrinking with accelerating tendency and the 2011 EU census led to a statistical amendment of –2,000 persons. Suburbanization played only a small role in Nordhausen. It occurred after the reunification for a short time in the 1990s, but most of the suburban areas were situated within the administrative city borders.

The birth deficit was 266 in 2012, this is -6.3 per 1,000 inhabitants (Thuringian average: -4.5; national average: -2.4). The net migration rate was -0.5 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2012 (Thuringian average: -0.8; national average: +4.6),[8] but is fluctuating relatively heavy for years. The most important regions of origin of Nordhausen migrants are rural areas of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt as well as foreign countries like Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria.

Like other eastern German cities, Nordhausen has only a small number of foreigners: circa 2.3% are non-Germans by citizenship and overall 4.6% are migrants (according to 2011 EU census). During recent years, the economic situation of the city improved somewhat: the unemployment rate in Nordhausen district declined from 24% in 2005 to 10% in 2013 with higher rates in the city than in the bordering rural municipalities. Due to the official atheism in former GDR, most of the population is non-religious. 16.2% are members of the Evangelical Church in Central Germany and 4.5% are Catholics (according to 2011 EU census).

Historical Population

|

|

|

|

- Data source since 1994: Thuringian state office for statistics

- ^ 1 December; 25,681 "native inhabitants", 3,582 "refugees with their residence in the area", 2,480 "refugees without fixed residence"

- ^ with mergers (Salza, Krimderode)

- ^ Census 2011: Bevölkerung der Gemeinden, erfüllenden Gemeinden und Verwaltungsgemeinschaften nach Geschlecht zum 31.12.2011 vor und nach dem Zensus 2011 im Vergleich in Thüringen from tls.thueringen.de, 2 June 2013

Culture, sights and cityscape

Museums

- The Flohburg/Nordhausen-Museum at Barfüßerstraße is the municipal museum of Nordhausen hosting an exhibition about the city's history.

- The Museum Tabakspeicher at Bäckerstraße is a trade history museum, showing some items of the last centuries economic history.

- The Kunsthaus Meyenburg at Alexander-Puschkin-Straße is Nordhausen's arthistorical museum and shows temporary exhibitions of art.

- The Mittelbau-Dora memorial north-west of the city hosts an exhibition about the history of this Nazi concentration camp and a memorial for its 20,000 victims.

- The IFA-Museum at Montaniastraße shows an exhibition of automotive engineering within an old Industrieverband Fahrzeugbau factory.

-

The Flohburg: Nordhausen-Museum

-

Tabakspeicher

-

Kunsthaus Meyenburg

-

Mittelbau-Dora (visitor's centre)

-

An IFA tractor (1949)

Cityscape

Nordhausen's cityscape is marked by the near total destruction during the bombings in 1945, extinguishing most of the historic city centre. There were four historic city parts before: the old town within the city wall on a hill east of the Zorge valley, the new town within the valley between the river in the west, the city wall in the east, Hohensteinerstraße in the north and Vor dem Vogel street in the south, the Altendorf suburbium in the north-west around Altendorf and Am Alten Tor street and the Altnordhausen suburbium in the south-east around St. Mary's Church on the hill. Altnordhausen and the new town are completely vanished, the old town was destroyed up to 90%, only some buildings around Barfüßerstraße, Domstraße and Bäckerstraße on the western edge remained, whereas Altendorf preserved entirely. During the 19th and 20th century, the city enlarged to all directions, the worker's districts were built up in the west at Zorge valley and Salza and to the east around Förstemannstraße and Leimbacher Straße. The mansion district developed in the north around Stolberger Straße and in the south and west along the railways, the big industrial areas are located.

The reconstruction after the World War II was carried out in altered manner, changing the grid and the structure of Nordhausen, which can be clearly seen along the new main streets Rautenstraße and Töpferstraße. Some areas were never built up again, for example those north and south of Kranichstraße and around Georgengasse. Peripheral Plattenbau settlements were built during the later GDR period in the east at Leimbacher Straße and in the north around the hospital. The village Salza in the north-west is grown together with Nordhausen since the 20th century.

Sights and architectural heritage

Churches

- The Nordhausen Holy Cross Cathedral is the catholic parish church of Nordhausen. It was never a bishop's seat but it's also called a cathedral because it is dating back to a cathedral chapter monastery. The building was established between 1180 and 1400 and shows both Romanesque and Gothic style elements.

- The St. Blaise's Church is the evangelical main church of Nordhausen. It was built during the second half of the 15th century in Gothic style.

- The St. Mary's Church in the valley at Altendorf (north-western historic city part) is an evangelical parish church today and was built as monastery around 1353 in Gothic style.

- The St. Mary's Church on the hill at Frauenberg hill (south-eastern historic city part) is also an evangelical parish church arose from a monastery. It was built in the 12th century in Romanesque style and destroyed (about 80%) in 1945 during the bombings. Later, the ruins were involved in a modern reconstruction.

- The Petri Tower is the remained steeple of the damaged St. Peter's Church within the city centre. It was built in 1362.

Furthermore, there were churches being destroyed by the 1945 bombings: the old main church St. Nicholas' and the new town's church St. Jacob's as well as the earlier abandoned monasteries of the Augustines, Franciscans and Dominicans.

-

Nordhausen Cathedral

-

St. Blaise's Church

-

St. Mary's Church in Altendorf

-

St. Mary's Church at Frauenberg

-

Petri Tower

Secular buildings

- The city wall was built between 13th and 15th century and remained in big parts (in the north, south-west and south-east).

- The town hall was built in Renaissance style between 1608 and 1610 and is one of only few buildings being rebuilt after the destruction by the bombings in 1945. The Nordhausen Roland is the city's landmark, it was established in 1717 as larger-than-life statue on the south-western corner of the town hall (wooden, today a copy, the original is shown in the museum).

- The Stadttheater was built between 1913 and 1917 and is in use a theatre until today.

- The Walkenrieder Hof is a former storage building at Waisenstraße, built in 1345 and now used as municipal archive.

- Some old buildings in city centre that survived the bombings in 1945 are only remained along Barfüßerstraße, Domstraße and Bäckerstraße on the western edge of the city centre and in the former suburbium Altendorf in the north-west. An interesting mansion district preserved north of the city centre with late-19th and early-20th century mansions.

-

City wall

-

Town hall

-

Roland at the town hall

-

Theatre

-

Walkenrieder Hof (on the right)

-

Remained old buildings at Altendorf

Economy and infrastructure

Agriculture, industry and services

Agriculture plays an important role to the present day. Approximately 57% of the municipal territory is in agricultural use. Cereals from the region are used in the making of a famous local spirit, the Nordhäuser Korn. Historically, sulfuric acid produced by the distillation of green vitriol (iron(II) sulfate) was known as Nordhausen oil of vitriol.

The primary industry of Nordhausen is in the production of heavy machinery. The region had a factory for the production of rail engines until 1942. Later the region's plants produced truck motors, augers and excavators. Today, engineering is still the most important industrial branch of Nordhausen, although many factories have had to close following the reunification of Germany in 1990. In 2012 there were 35 companies of 20 workers or more were present in the industrial sector, all together employing 4,000 persons and generating an annual turnover of €800 mio,[9] making Nordhausen the industrial core of Thuringia today.

Nordhausen is the biggest city in a circuit of 60 km (37 mi), making it an important regional service hub for retail, medicine, education, government and culture (theatre, cinema etc.). A major shopping centre is the Südharz Galerie at Bahnhofstraße, and the Südharz Klinikum is one of the biggest hospitals in Thuringia.

Transport

Nordhausen has been a railway node since the late 19th century. The Halle–Kassel railway was opened in 1866/67, the South Harz Railway in 1869 and the Nordhausen–Erfurt railway also in 1869. In 1897, the narrow-gauge Trans-Harz Railway followed as the last one. Today, there are regional express trains to Halle in the east and Kassel in the west as well as local trains to Halle, Heiligenstadt, Erfurt and Göttingen (via Northeim), running every one to two hours. Nordhausen station is the main station, a second one is Nordhausen-Salza on the South Harz line. The narrow-gauge Trans-Harz-Railway is linked with the tramway network in a Tram-train system with many stops within Nordhausen.

Nordhausen is located on the Bundesautobahn 38 from Göttingen in the west to Halle and Leipzig in the east, opened in the 2000s. Furthermore, there are two Bundesstraßen connecting Nordhausen: the Bundesstraße 4 is a link to Erfurt in the south and to Braunschweig through the Harz mountains in the north and the Bundesstraße 243 connects Nordhausen with Hildesheim in the north-west. The former Bundesstraße 80 was annulled after the opening of the parallel Bundesautobahn 38 and the Bundesstraße 81 as a connection to Magdeburg starts a few kilometres north of the city at B 4. The B 4 (southern branch) and the B 243 shall be enlarged because of their importance as connections to and between Erfurt and Lower Saxony. Furthermore, there are important secondary roads to Heringen in the south-east and to Buchholz in the north-east.

The nearest airports are the Erfurt-Weimar Airport, 80 km (50 mi) to the south, the Leipzig/Halle Airport, 120 km (75 mi) to the east and the Hannover Airport, 150 km (93 mi) to the north-west.

For cycling, the long-distance Südharzroute trail network offers 10 trails in the region around Nordhausen.

The Nordhausen tramway network forms an important part of the public transport system, established in 1900. Furthermore, there are inner-city and regional bus services.

Education

Nordhausen has a Fachhochschule (University of Applied Sciences) with 2,500 students that offers Bachelor's and Master's degrees in business administration, public management, and business engineering, among others.[10] Furthermore, there are two Gymnasiums in Nordhausen.

Politics

Mayor and city council

The first freely elected mayor after German reunification was Barbara Rinke of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who served from 1994 to 2012. She was succeeded by Klaus Zeh of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 2012 until his resignation in 2017. Independent Kai Buchmann was elected in the resulting election. The most recent mayoral election was held on 10 September 2017, with a runoff held on 24 September, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Inge Klaan | Christian Democratic Union | 5,456 | 35.0 | 7,167 | 33.8 | |

| Kai Buchmann | Independent | 4,530 | 29.1 | 14,019 | 66.2 | |

| Jutta Krauth | Social Democratic Party | 2,917 | 18.7 | |||

| Michael Mohr | The Left | 1,776 | 11.4 | |||

| Dirk Erfurt | Alliance 90/The Greens | 894 | 5.7 | |||

| Valid votes | 15,573 | 99.0 | 21,186 | 98.5 | ||

| Invalid votes | 157 | 1.0 | 314 | 1.5 | ||

| Total | 15,730 | 100.0 | 21,500 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 35,264 | 44.6 | 35,150 | 61.2 | ||

| Source: Wahlen in Thüringen | ||||||

The most recent city council election was held on 26 May 2019, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Lead candidate | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | Steffen Iffland | 11,942 | 22.2 | 8 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | Michael Mohr | 11,734 | 21.8 | 8 | ±0 | ||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | Jörg Prophet | 11,299 | 21.0 | New | 8 | New | |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | Hans-Georg Müller | 9,387 | 17.4 | 6 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | Sylvia Spehr | 4,912 | 9.1 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | Manuel Thume | 3,857 | 7.2 | 3 | |||

| National Democratic Party (NPD) | Ralf Friedrich | 688 | 1.3 | 0 | |||

| Valid votes | 18,153 | 97.5 | |||||

| Invalid votes | 467 | 2.5 | |||||

| Total | 18,620 | 100.0 | 36 | ±0 | |||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 34,843 | 53.4 | |||||

| Source: Wahlen in Thüringen | |||||||

Twin towns – sister cities

Nordhausen is twinned with:[11]

Charleville-Mézières, France (1978)

Charleville-Mézières, France (1978) Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland (1983)

Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland (1983) Bochum, Germany (1990)

Bochum, Germany (1990) Beit Shemesh, Israel (1992)

Beit Shemesh, Israel (1992)

Notable people

- Eduard Baltzer (1814–1887), reformer and democrat

- Julius Bergmann (1861–1940), painter

- Rolf Kalmuczak (1938–2007), author

- Volker Beck (born 1956), athlete

- Gitta Escher (born 1957), devices gymnast

- Ariane Friedrich (born 1984), high jumper

- Maximilian Beyer (born 1993), racing cyclist

References

- ^ Gewählte Bürgermeister - aktuelle Landesübersicht, Freistaat Thüringen, accessed 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden, erfüllenden Gemeinden und Verwaltungsgemeinschaften in Thüringen Gebietsstand: 31.12.2022" (in German). Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik. June 2023.

- ^ a b "Nordhausen". The Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Joseph; Seligsohn, M. "Nordhausen". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "8th Air Force 1944 Chronicles". Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ Béon, Yves (1997). Planet Dora: A Memoir of the Holocaust and the Birth of the Space Age. (translated from the French La planète Dora by Béon & Richard L. Fague). Westview Press, Div. of Harper Collins. p. XIX, XXI, XXII, XXIV. ISBN 0-8133-3272-9.

- ^ "Soviet rocket building in Thuringia" Archived 2008-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ According to Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik

- ^ According to Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik

- ^ Fachhochschule Nordhausen

- ^ "Partnerstädte". nordhausen.de (in German). Nordhausen. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

External links

- Official website

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- NordhausenWiki