Suicide

| Suicide | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

Suicide (Latin suicidium, from sui caedere, "to kill oneself") is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair, the cause of which can attributed to a mental disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, alcoholism, or drug abuse.[1] Stress factors such as financial difficulties or troubles with interpersonal relationships often play a significant role.[2]

Over one million people die by suicide every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that it is the 13th leading cause of death worldwide[3] and the National Safety Council rates it sixth in the United States.[4] It is a leading cause of death among teenagers and adults under 35.[5][6] The rate of suicide is far higher in men than in women, with males worldwide three to four times more likely to kill themselves than females.[7][8] There are an estimated 10 to 20 million non-fatal attempted suicides every year worldwide.[9]

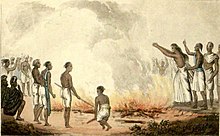

Views on suicide have been influenced by broader cultural views on existential themes such as religion, honor, and the meaning of life. The Abrahamic religions traditionally consider suicide an offense towards God due to the belief in the sanctity of life. It was often regarded as a serious crime and that view remains commonplace in modern Western thought. However, before the rise of Christianity, suicide was not seen as automatically immoral in ancient Greek and Roman culture. Conversely, during the samurai era in Japan, seppuku was respected as a means of atonement for failure or as a form of protest. Sati is a Hindu funeral practice, now outlawed, in which the widow was expected to immolate herself on her husband's funeral pyre, either willingly or under pressure from the family and society.[10] In the 20th and 21st centuries, suicide in the form of self-immolation has been used as a medium of protest, and the form of kamikaze and suicide bombings as a military or terrorist tactic.

Medically assisted suicide (euthanasia, or the right to die) is a controversial issue in modern ethics. The defining characteristic is the focus on people who are terminally ill, in extreme pain, or possessing (actual or perceived) minimal quality of life resulting from an injury or illness.

Self-sacrifice on behalf of another is not necessarily considered suicide; the subjective goal is not to end one's own life, but rather to save the life of another. However, in Émile Durkheim's theory, such acts are termed "altruistic suicide."[11]

Classification

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Euthanasia | Individuals who wish to end their own lives may enlist the assistance of another party to achieve death. The other person, usually a family member or physician, may help carry out the act when the individual lacks the physical capacity to do so alone, even if supplied with the means. Assisted suicide is a contentious moral and political issue in many countries, as seen in the scandal surrounding Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a US medical practitioner who supported euthanasia and was convicted of having helped patients end their own lives, for which he served an eight year prison term.[12] |

| Murder–suicide | A murder–suicide is an act in which an individual kills one or more other persons immediately before or at the same time as him or herself. The motivation for the murder in murder–suicide can be purely criminal in nature or be perceived by the perpetrator as an act of care for loved ones in the context of severe depression. |

| Suicide attack | A suicide attack is an act in which an attacker perpetrates an act of violence against others, typically to achieve a military or political goal, which simultaneously results in his or her own death. Suicide bombings are often regarded as an act of terrorism by the targeted community. Historical examples include the assassination of Czar Alexander II, the kamikaze attacks launched by Japanese air pilots during the Second World War, and larger scale attacks, such as the September 11th attacks. |

| Mass suicide | Some suicides are performed under social pressure or coordinated among a group of individuals. Mass suicides can take place with as few as two people, often referred to as a suicide pact. An example of a larger group is the 1978 "Jonestown" cult suicide, in which 918 members of the Peoples Temple, an American cult led by Jim Jones, ended their lives by drinking grape Flavor Aid laced with cyanide.[13][14][15] Over 10,000 Japanese civilians committed suicide in the last days of the Battle of Saipan in 1944, some jumping from "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".[16] |

| Suicide pact | A suicide pact describes the suicides of two or more individuals in an agreed upon plan. The plan may be to die together, or separately and closely timed. Suicide pacts are generally distinct from mass suicides in that the latter refers to a larger number of people who kill themselves together for a common ideological reason, often within a religious, political, military or paramilitary context. In contrast, suicide pacts typically involve small groups of more intimately related people (commonly spouses, romantic partners, family members, or friends), whose motivations are intensely personal and individual. |

| Defiance or protest | Suicide is sometimes committed as an act of defiance or political protest such as the suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia whose treatment at the hands of the authorities led to a revolt that overthrew the ruling regime and touched off the Arab Spring. During the sectarian strife in Northern Ireland known as "The Troubles" a hunger strike was launched by the provisional IRA, demanding that their prisoners be reclassified as prisoners of war rather than as terrorists. The infamous 1981 hunger strikes, led by Bobby Sands resulted in 10 deaths. The cause of death was recorded as "starvation, self-imposed" rather than suicide by the coroner; this was modified to simply "starvation" on the death certificates after protest from the deceased striker's families.[17] |

| Dutiful suicide | Dutiful suicide is an act of fatal self violence at one's own hands done in the belief that it will secure a greater good, rather than to escape harsh or impossible conditions. It can be voluntary, to relieve some dishonor or punishment, or imposed by threats of death or reprisals on one's family or reputation as in the forced suicide of German general Erwin Rommel during World War II. He was found to have foreknowledge of the July 20 Plot on Hitler's life and was threatened with public trial, execution, and reprisals on his family unless he took his own life.[18] It is a traditional practice in some cultures, such as the heavily ritualized Japanese custom of seppuku. |

| Escape | In extenuating situations where continuing to live would be intolerable, some people use suicide as a means of escape. Some inmates in Nazi concentration camps are known to have killed themselves by deliberately touching the electrified fences.[19] Over 200,000 debt-ridden farmers in India have committed suicide since 1997.[20] |

Risk factors

Clinical studies have shown that underlying mental disorders are present in 87% to 98% of suicides, however, there are a number of other factors are correlated with suicide risk, including drug addiction, availability of means, family history of suicide, or previous head injury.[22][23]

Socio-economic factors such as unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and discrimination may trigger suicidal thoughts.[24] Poverty may not be a direct cause, but it can increase the risk of suicide, as impoverished individuals are a major risk group for depression.[25] A history of childhood physical or sexual abuse[26] or time spent in foster care.[27][28][29]

Hopelessness, the feeling that there is no prospect of improvement in one's situation, is a strong indicator of suicide. One study found that among a group of people previously hospitalized for suicidal tendencies, 91% of those who scored a 10 or higher on the Beck Hopelessness Scale would eventually commit suicide.[30] Perceived burdensomeness[31] a feeling that one's existence is a burden to others such as family members is often coupled with hopelessness as are the feelings of loneliness,[32] either subjectively (i.e., the feeling), or objectively (i.e., living alone or being without friends and lacking social support[33]) and the feeling of not belonging[34] as strong mediators of suicidal ideation.

Advocacy of suicide has been cited as a contributing factor. Intelligence may also be a factor. Initially proposed as a part of an evolutionary psychology explanation, which posited a minimum intelligence required for one to commit suicide, the positive correlation between IQ and suicide has been replicated in a number of studies.[35][36][37][38][39] Some scientists doubt, however, that intelligence can be a cause of suicide,[40] and intelligence is no longer a predictor of suicide when regressed with national religiousness and perceptions of personal health.[41] According to the American Psychiatric Association, "religiously unaffiliated subjects had significantly more lifetime suicide attempts and more first-degree relatives who committed suicide than subjects who endorsed a religious affiliation."[42] Moreover, individuals with no religious affiliation had fewer moral objections to suicide than believers.[42]

One study found that a lack of social support, a deficit in feelings of belongingness and living alone were crucial predictors of a suicide attempt.[43] One study found that among prison inmates, suicide was more likely among inmates who had committed a violent crime.[44]

Medical conditions

In various studies a significant association was found between suicidality and underlying medical conditions including chronic pain,[45] mild brain injury, (MBI) or traumatic brain injury (TBI).[46][47] The prevalence of increased suicidality persisted after adjusting for depressive illness and alcohol abuse. In patients with more than one medical condition the risk was particulaly high, suggesting a need for increased screening for suicidality in general medical settings.[48][49]

Sleep disturbances such as insomnia[50] and sleep apnea have been cited in various studies as risk indicators for depression and suicide. In some instances the sleep disturbance itself may be the risk factor independent of depression.[51]

A careful medical evaluation is recommended for all people presenting with psychiatric symptoms as many medical conditions present with psychiatric symptomatology. The major medical conditions presenting with psychiatric symptoms in order of frequency were infectious, pulmonary, thyroid, diabetic, hematopoietic, hepatic and CNS diseases.[52] Conservative estimates are that 10% of all psychological symptoms may be due to undiagnosed medical conditions,[53] with the results of one study suggesting that about 50% of individuals with a serious mental illness "have general medical conditions that are largely undiagnosed and untreated and may cause or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms".[54][55]

Mental disorders

Certain mental disorders are often present at the time of suicide. It is estimated that from 87% to 98% of suicides are committed by people with some type of mental disorder.[56] Broken down by type: mood disorders are present in 30%, substance abuse in 18%, schizophrenia in 14%, and personality disorders in 13% of suicides.[57] About 5% of people with schizophrenia die of suicide.[58] Major depression and alcoholism are the specific disorders most strongly correlated with suicide risk. Risk is greatest during the early stages of illness among people with mood disorders, such as major depression or bipolar disorder.[59]

Depression is among the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders;[60][61] increasingly diagnosed across various segments of the worldwide population.[62][63] 17.6 million Americans are affected each year; approximately 1 in 6 people. Within the next twenty years, depression is expected to become the leading cause of disability in developed nations and the second leading cause of disability worldwide.[64] While the psychological and medical communities no longer classify acts of self-harm as suicide attempts, recent research has indicated that the presence of self-injurious behavior may be correlated to increased suicide risk.[65] While there is a correlation between self-harm and suicide, it is not believed to be causal; both are most likely a joint effect of depression.[66] This may also be classified as deliberate self-harm and is most common in younger people, but has been increasing in recent years in people of all ages.[67]

Most people who attempt suicide do not complete the act on their first attempt. However, a history of suicide attempts is correlated with increased risk of eventual completion of a suicide.[68]

Biology

Some mental disorders identified as risk factors for suicide often may have an underlying biological basis.[69][70] Serotonin is a vital brain neurotransmitter; in those who have attempted suicide it has been found that they have lower serotonin levels, and individuals who have completed suicide have the lowest levels.[71][72] This dysregulation in the serotonin pathway has been identified, in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. This alteration in the brain has been found to be a risk factor for suicide independent of a history of a major depression "indicating that it is involved in the predisposition to suicide in many psychiatric disorders."[73][74][75]

There is evidence that there may be an underlying neurobiological basis for suicide risk independent of the inheritable genetic factors responsible for the major psychiatric disorders associated with suicide.[76] Genetic inheritance accounts for roughly 30–50% of the variance in suicide risk between individuals.[77][78][78] Having a parent who has committed suicide is a strong predictor of suicide attempts.[79][80][81]

Epigenetics, the study of changes in genetic expression in response to environmental factors which do not alter the underlying DNA, may also play a role in determining suicide risk.[82][83][84]

Perceived burdensomeness to others

Several studies have found perceived burdensomeness to others to be a particularly strong risk factor. It also differentiates between attempted vs. completed suicide and predicts lethality of suicide method unlike feelings of hopelessness and emotional pain. Likely related to this, completed suicides are characterized by altruistic feelings while non-lethal self-injuries are characterized by feelings of anger or self-punishment.[85]

An evolutionary psychology explanation for this is that suicide may under some circumstances improve inclusive fitness. This may occur if the person committing suicide will not have more children (even if not committing suicide) and takes away resources from relatives by staying alive. An objection is that some suicides, such as healthy adolescents committing suicide, likely do not increase inclusive fitness. One response is that adaptations to the very different ancestral environment may be maladaptive in the current one."[85][86]

Substance abuse

Substance abuse is the second most common risk factor for suicide after major depression and bipolar disorder.[87] Both chronic substance misuse as well as acute substance abuse are associated with suicide.[88] This is attributed to the intoxicating, disinhibiting, and dissociative effects of many psychoactive substances. When combined with personal grief, such as bereavement, the risk of suicide is greatly increased.[89] More than 50% of suicides have some relation to alcohol or drug use and up to 25% of suicides are committed by drug addicts and alcoholics. This figure is even higher with alcohol or drug use among adolescents, playing a role in up to 70% of suicides. It has been recommended that all drug addicts or alcoholics undergo investigation for suicidal thoughts due to their high risk of suicide.[90] An investigation in the New York Prison Service found that 90% of inmates who committed suicide had a history of substance abuse.[91]

| Substance abused | Effects related to suicide |

|---|---|

| Cocaine | Misuse of drugs such as cocaine have a high correlation with suicide. Suicide is most likely to occur during the "crash" or withdrawal phase in chronic cocaine-dependent users. Polysubstance misuse is more often associated with suicide in younger adults, whereas suicide from alcoholism is more common in older adults. In San Diego it was found that 30% of suicides by people under the age of 30 had used cocaine. In New York City in the early 1990s, during the height of a crack epidemic, 1 in 5 people who committed suicide were found to have recently consumed cocaine. The "come down" or withdrawal phase of cocaine use can result in intense, acute depressive symptoms as well as other distressing mental effects, all of which contribute to an increased risk of suicide.[92][93] |

| Methamphetamine | Methamphetamine use has a strong association with depression and suicide as well as a range of other adverse effects on physical and mental health.[94] |

| Opioids | Heroin users have a death rate nearly 13 times that of their non-using peers. Deaths among heroin users attributed to suicide range from 3% to 35%, though determining the difference between a suicide and an accidental overdose can be impossible without evidence of state of mind. Overall, heroin users are 14 times more likely than their non-using peers to die from suicide.[95] Major depressive disorder was found in 25% of entrants to treatment for heroin dependence in Australia.[96] |

| Benzodiazepines | Chronic use or abuse of prescribed benzodiazepines is associated with depression as well as increased suicide risk. Care should be taken when prescribing to at-risk individuals and patient populations.[97][98][99] Depressed adolescents who were taking benzodiazepines were found to have a greatly increased risk of self harm or suicide, though the sample size in this study was too small to provide generalizable conclusions. The effects of benzodiazepines in individuals under the age of 18 is not well understood. Additional caution may be required for depressed adolescents using benzodiazepines.[100] Benzodiazepine dependence often results in an increasingly deteriorating clinical picture which includes social deterioration leading to comorbid alcoholism and drug abuse. Suicide is a common outcome of chronic benzodiazepine dependence. Benzodiazepine misuse or misuse of other CNS depressants increases the risk of suicide in drug misusers.[101][102] 11% of males and 23% of females with a sedative hypnotic misuse habit commit suicide.[103] Benzodiazepine withdrawal also leads to an increased risk of suicide.[104] |

| Cigarettes | There have been various studies showing a positive link between smoking, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.[105][106] In a study conducted among nurses, those smoking between 1 to 24 cigarettes per day had twice the suicide risk; 25 cigarettes or more, 4 times the suicide risk, as compared with those who had never smoked.[107][108] In a study of 300,000 male U.S. Army soldiers, a definitive link between suicide and smoking was observed with those soldiers smoking over a pack a day having twice the suicide rate of non-smokers.[109] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol misuse is associated with a number of mental health disorders, and alcoholics have a very high suicide rate.[110] It has been found that drinking 6 drinks or more per day results in a sixfold increased risk of suicide.[92][93] High rates of major depressive disorder occur in heavy drinkers and those who misuse alcohol. Controversy has previously surrounded whether those who misused alcohol who developed major depressive disorder were self medicating (which may be true in some cases), but recent research has now concluded that chronic excessive alcohol intake itself directly causes the development of major depressive disorder in a significant number of alcoholics.[111] |

Problem gambling

Problem gambling is often associated with increased suicidal ideation and attempts compared to the general population.[112][113][114]

Early onset of problem gambling increases the lifetime risk of suicide.[115] However, gambling-related suicide attempts are usually made by older people with problem gambling.[116] Both comorbid substance use[117][118] and comorbid mental disorders increase the risk of suicide in people with problem gambling.[116]

A 2010 Australian hospital study found that 17% of suicidal patients admitted to the Alfred Hospital's emergency department were problem gamblers.[119]

Media coverage

Various studies have suggested that how the media presents depictions of suicide may have a negative effect[120] and trigger the possibility of suicide contagion also known as the Werther effect, named after the protagonist in Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther who committed suicide.[121][122] This risk is greater in adoloescents who may romantacize death.[123][124][125] It appears that while news media has a significant effect, that of entertainment media is equivocal.[126]

The opposite of the Werther effect is the Papageno effect in which coverage of effective coping mechanisms, coping in adverse circumstances, as covered in the media about suicidal ideation, may have protective effects. The term is based upon a character in Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute named Papageno who fearing the loss of a loved one was going to commit suicide until three boys showed him different ways to cope.[127]

Methods

The leading method of suicide varies dramatically between countries. The leading methods in different regions include hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms.[128] A 2008 review of 56 countries based on WHO mortality data found that hanging was the most common method in most of the countries,[129] accounting for 53% of the male suicides and 39% of the female suicides.[130] Worldwide 30% of suicides are from pesticides. The use of this method however varies markedly from 4% in Europe to more than 50% in the Pacific region.[131] In the United States 52% of suicides involve the use of firearms.[132] Asphyxiation (such as with a suicide bag) and poisoning are fairly common as well. Together they comprised about 40% of U.S. suicides. Other methods of suicide include blunt force trauma (jumping from a building or bridge, self-defenestrating, stepping in front of a train, or car collision, for example). Exsanguination or bloodletting (slitting one's wrist or throat), intentional drowning, self-immolation, electrocution, and intentional starvation are other suicide methods. Individuals may also intentionally provoke another person into administering lethal action against them, as in suicide by cop.

Whether or not exposure to suicide is a risk factor for suicide is controversial.[133] A 1996 study was unable to find a relationship between suicides among friends,[134] while a 1986 study found increased rates of suicide following the television of news stories regarding suicide.[135]

Prevention

Suicide prevention is a term used for the collective efforts to reduce the incidence of suicide through preventive measures. Various strategies restrict access to the most common methods of suicide, such as firearms or toxic substances like pesticides, and have proved to be effective in reducing suicide rates. Studies supported by empirical data have indicated that adequate prevention, diagnosis and treatment of depression and alcohol and substance abuse can reduce suicide rates, as does follow-up contact with those who have made a suicide attempt.[136] Although crisis hotlines are common there is little evidence to support or refute their effectiveness.[137][138]

The Best Practices Registry (BPR) For Suicide Prevention is a registry of various suicide intervention programs maintained by the American Association of Suicide Prevention. The programs are divided, with those in Section I listing evidence-based programs: interventions which have been subjected to indepth review and for which evidence has demonstrated positive outcomes. Section III programs have been subjected to review.[139][140]

In various countries, individuals who are at imminent risk of harming themselves or others may voluntarily check themselves into a hospital emergency department; this may also be done on an involuntary basis on the referral of various individuals acting in an official capacity such as the police. This is referred to by various names such as being "committed" or "sectioned". They will be placed on suicide watch until an emergency physician or mental health professional determines whether inpatient care at a mental health care facility is warranted and may hold the individual for a period of usually three days duration. A court hearing may be held to determine the individual's competence. In most states, a psychiatrist may hold the person for a specific time period without a judicial order. If the psychiatrist determines the person to be a threat to himself or others, the person may be admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric treatment facility. After this time the person must be discharged or appear in front of a judge.[141]

Screening

The U.S. Surgeon General has suggested that screening to detect those at risk of suicide may be one of the most effective means of preventing suicide in children and adolescents.[142] There are various screening tools in the form of self-report questionnaires to help identify those at risk such as the Beck Hopelessness Scale and Is Path Warm? A number of these self-report questionnaires have been tested and found to be valid for use among adolescents and young adults.[143] There is, however, a high rate of false-positive identification and those deemed to be at risk should ideally have a follow-up clinical interview.[144] The predictive quality of these screening questionnaires has not been conclusively validated, so it is not possible to determine if those identified at risk of suicide will actually commit suicide.[145] Asking about or screening for suicide does not appear to increase the risk.[146]

In approximately 75% of completed suicides the individuals had seen a physician within the year before their death, including 45% to 66% within the prior month. Approximately 33% to 41% of those who completed suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year, including 20% within the prior month. These studies suggest an increased need for effective screening.[147][148][149][150][151]

Treatment

There are various treatment modalities to reduce the risk of suicide by addressing the underlying conditions causing suicidal ideation, including, depending on case history, medical,[152] pharmacological,[153] and psychotherapeutic talk therapies.[154]

The conservative estimate is that 10% of individuals with psychiatric disorders may have an undiagnosed medical condition causing their symptoms,[155] upwards of 50% may have an undiagnosed medical condition which if not causing is exacerbating their psychiatric symptoms.[156][157] Illegal drugs and prescribed medications may also produce psychiatric symptoms.[158] Effective diagnosis and if necessary medical testing which may include neuroimaging[159] to diagnose and treat any such medical conditions or medication side effects may reduce the risk of suicidal ideation as a result of psychiatric symptoms, most often including depression, which are present in up to 90-95% of cases.[160]

Recent research has shown that treatment with lithium has been effective with lowering the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder to the same levels as the general population.[161] Low doses of Lithium with minimal side effects has also proven effective in lowering the suicide risk in those with unipolar depression as well.[162]

There are multiple evidence-based psychotherapeutic talk therapies available to reduce suicidal ideation such as dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) for which multiple studies have reported varying degrees of clinical effectiveness in reducing suicidality. Benefits include a reduction in self-harm behaviours and suicidal ideations.[163][164] Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP) is a form of DBT adapted for adolescents at high risk for repeated suicide attempts.[165]

Epidemiology

Worldwide suicide rates have increased by 60% in the past 45 years, mainly in the developing countries and is currently the tenth leading cause of death[1] with about a million people dying by suicide annually, a global mortality rate of 16 suicides per 100,000 people, or a suicide every 40 seconds.[167] According to 2007 data, suicides in the U.S. outnumber homicides by nearly 2 to 1. Suicide ranks as the 11th leading cause of death in the country, ahead of liver disease and Parkinson's.[168]

Gender

In the Western world, males die much more often by means of suicide than do females, although females attempt suicide more often. Some medical professionals believe this stems from the fact that males are more likely to end their lives through effective violent means, while women primarily use less severe methods such as overdosing on medications. In most countries, drug overdoses account for about two-thirds of suicides among women and one-third among men.[67]

Alcohol and drug use

In the United States 16.5% of suicides are related to alcohol.[169] Alcoholics are 5 to 20 times more likely to kill themselves, while the misuse of other drugs increases the risk 10 to 20 times. About 15% of alcoholics commit suicide, and about 33% of suicides in the under 35 age group have a primary diagnosis of alcohol or other substance misuse; over 50% of all suicides are related to alcohol or drug dependence. In adolescents alcohol or drug misuse plays a role in up to 70% of suicides.[90][170]

Ethnicity

National suicide rates differ significantly between countries and amongst ethnic groups within countries.[171] For example, in the U.S., non-Hispanic Caucasians are nearly 2.5 times more likely to kill themselves than African Americans or Hispanics.[172]

Social aspects

Legislation

In some jurisdictions, an act or incomplete act of suicide is considered to be a crime. More commonly, a surviving party member who assisted in the suicide attempt will face criminal charges.

In Brazil, if the help is directed to a minor, the penalty is applied in its double and not considered as homicide. In Italy and Canada, instigating another to suicide is also a criminal offense. In Singapore, assisting in the suicide of a mentally handicapped person is a capital offense. In India, abetting suicide of a minor or a mentally challenged person can result in a maximum 1 year prison term with a possible fine.[173]

In Germany, the following laws apply to cases of suicide:[174]

- Active euthanasia (killing on request) is prohibited by article 216 of the StGB (Strafgesetzbuch, German Criminal Code), punishable with six months to five years in jail

- German law interprets suicide as an accident and anyone present during suicide may be prosecuted for failure to render aid in an emergency. A suicide legally becomes an emergency when a suicidal person loses consciousness. Failure to render aid is punishable under article 323c of the StGB, with a maximum one year jail sentence.

Switzerland has recently taken steps to legalize assisted suicide for the chronically mentally ill. The high court in Lausanne, in a 2006 ruling, granted an anonymous individual with longstanding psychiatric difficulties the right to end his own life. At least one leading American bioethicist, Jacob Appel of Brown University, has argued that the American medical community ought to condone suicide in certain individuals with mental illness.[175]

Religious views

In most forms of Christianity, suicide is considered a sin, based mainly on the writings of influential Christian thinkers of the Middle Ages, such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas; suicide was not considered a sin under the Byzantine Christian code of Justinian, for instance.[176][177] In Catholic doctrine, the argument is based on the commandment "Thou shalt not kill" (made applicable under the New Covenant by Jesus in Matthew 19:18), as well as the idea that life is a gift given by God which should not be spurned, and that suicide is against the "natural order" and thus interferes with God's master plan for the world.[178] However, it is believed that mental illness or grave fear of suffering diminishes the responsibility of the one completing suicide.[179] Counter-arguments include the following: that the sixth commandment is more accurately translated as "thou shalt not murder", not necessarily applying to the self; that God has given free will to humans; that taking one's own life no more violates God's Law than does curing a disease; and that a number of suicides by followers of God are recorded in the Bible with no dire condemnation.[180]

Judaism focuses on the importance of valuing this life, and as such, suicide is tantamount to denying God's goodness in the world. Despite this, under extreme circumstances when there has seemed no choice but to either be killed or forced to betray their religion, Jews have committed individual suicide or mass suicide (see Masada, First French persecution of the Jews, and York Castle for examples) and as a grim reminder there is even a prayer in the Jewish liturgy for "when the knife is at the throat", for those dying "to sanctify God's Name" (see Martyrdom). These acts have received mixed responses by Jewish authorities, regarded both as examples of heroic martyrdom, whilst others state that it was wrong for them to take their own lives in anticipation of martyrdom.[181]

Suicide is not allowed in Islam.[182] [dubious ]

In Hinduism, suicide is generally frowned upon and is considered equally sinful as murdering another in contemporary Hindu society. Hindu Scriptures state that one who commits suicide will become part of the spirit world, wandering earth until the time one would have otherwise died, had one not committed suicide.[183] However, Hinduism accept a man's right to end one's life through the non-violent practice of fasting to death, termed Prayopavesa.[184] But Prayopavesa is strictly restricted to people who have no desire or ambition left, and no responsibilities remaining in this life.[184] Jainism has a similar practice named Santhara. Sati, or self-immolation by widows was prevalent in Hindu society during the Middle Ages.

Philosophy

Some see suicide as a legitimate matter of personal choice and a human right (colloquially known as the right to die movement). Supporters of this position maintain that no one should be forced to suffer against their will, particularly from conditions such as incurable disease, mental illness, and old age that have no possibility of improvement. Proponents of this view reject the belief that suicide is always irrational, arguing instead that it can be a valid last resort for those enduring major pain or trauma.[185] This perspective is most popular and has a good deal of support in continental Europe, where euthanasia and other such topics are commonly discussed in parliament.[186]

A narrower segment of this group considers suicide something between a grave but condonable choice in some circumstances and a sacrosanct right for anyone (even a young and healthy person) who believes they have rationally and conscientiously come to the decision to end their own lives. Notable supporters of this school of thought include Friedrich Nietzsche, and Scottish empiricist David Hume.[187] Bioethicist Jacob Appel has become the leading advocate for this position in the United States.[188][189] Adherents of this view often advocate the abrogation of statutes that restrict the liberties of people known to be suicidal, such as laws permitting their involuntary commitment to mental hospitals.

Locations

Some landmarks have become known for high levels of suicide attempts. The four most popular locations in the world are reportedly San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge, Toronto's Bloor Street Viaduct (before the construction of the Luminous Veil),[190] Japan's Aokigahara Forest and England's Beachy Head.[191] In 2005 the Golden Gate Bridge had a count exceeding 1,200 jumpers since its construction in 1937.[192] In 1997 the Bloor Street Viaduct had one suicide every 22 days,[193] and in 2002 Aokigahara had a record of 78 bodies found within the forest, replacing the previous record of 73 in 1998.[194] The suicide rate of these places is so high that numerous signs, urging potential victims of suicide to seek help, have been posted.[195]

Advocacy

Advocacy of suicide has occurred in many cultures and subcultures. The Japanese military during World War II encouraged and glorified kamikaze attacks, and Japanese society as a whole has been described as suicide 'tolerant' (see Suicide in Japan).

William Francis Melchert-Dinkel, 47 years old in May 2010, from Faribault, Minnesota, a licensed nurse from 1991 until February 2009, stands accused of encouraging people to commit suicide while he watched on a webcam.[196][197][198][199]

A study by the British Medical Journal found that Web searches for information on suicide are likely to return sites that encourage, and even facilitate, suicide attempts.[200] There is some concern that such sites may push the suicidal over the edge.[201] Some people form suicide pacts with people they meet online.[202] Becker writes, "Suicidal adolescent visitors risk losing their doubts and fears about committing suicide. Risk factors include peer pressure to commit suicide and appointments for joint suicides. Furthermore, some chat rooms celebrate chatters who committed suicide."[203]

Language

Because suicide was a crime in various countries, including in England and Wales which decriminalized it in 1961, the word 'commit' has traditionally been used in reference to it. Organisations such as the BBC and the Samaritans have stopped using this word because of its negative connotation. 'Attempt' suicide or other phrases are preferred.[204] The Guardian and The Observer also avoid the phrase, preferring the use of "killed him or herself".[205]

Other species

"Suicide" has been observed in salmonella seeking to overcome competing bacteria by triggering an immune system response against them.[206] Suicidal defences by workers are also noted in a Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus where a small group of ants leaves the security of the nest after sealing the entrance from the outside each evening.[207]

Pea aphids, when threatened by a ladybug, can explode themselves, scattering and protecting their brethren and sometimes even killing the lady bug.[208] Some species of termites have soldiers that explode, covering their enemies with sticky goo.[209][210]

Asian black bears being used as "bile bears" are known to frequently try to kill themselves as a result of the severe pain caused by the permanent holes in their abdomen and gall bladder.[211][212]

There have been anecdotal reports of dogs, horses, and dolphins committing suicide, but with little conclusive evidence.[213] There has been little scientific study of animal suicide.[214]

See also

- Bullycide

- Parasuicide

- Rational suicide

- Senicide

- Stigmatized property

- Suicide bridge

- Suicide note

- Suicide survivor

Suicide prevention organizations

- Samaritans (charity)

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- Suicide Prevention Action Network USA

- Campaign Against Living Miserably

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Books & Film

| class="col-break " |

Lists

- List of suicide crisis lines

- List of countries by suicide rate

- List of suicide sites

- List of suicides

Footnotes

- ^ a b Hawton K, van Heeringen K (2009). "Suicide". Lancet. 373 (9672): 1372–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. PMID 19376453.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "www.uvm.edu" (PDF).

- ^ Bruce Gross, Forrensic Examiner, Summer, 2006

- ^ see the PDF

- ^ "CIS: UN Body Takes On Rising Suicide Rates – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2006".

- ^ O'Connor, Rory; Sheehy, Noel (29 Jan 2000). Understanding suicidal behaviour. Leicester: BPS Books. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-85433-290-5.

- ^ http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=VB3OezIoI44C&pg=PA311&dq=rates+of+suicide+of+men+are+three+to+four+times+higher+than+for+women&hl=en&ei=ke2dTuiCAZH6sgaO9uj5CA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Gelder et al, 2005 p169. Psychiatry 3rd Ed. Oxford: New York

- ^ Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A (2002). "Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective". World Psychiatry. 1 (3): 181–5. PMC 1489848. PMID 16946849.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Indian woman commits sati suicide". Bbc.co.uk. 2002-08-07. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Blake JA (1978 Spring). "Death by hand grenade: altruistic suicide in combat". Suicide & life-threatening behavior. 8 (1). Suicide Life Threat Behav.: 46–59. PMID 675772.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Monica Davey. "Kevorkian Speaks After His Release From Prison". The New York Times. June 4, 2007. Note: Kevorkian was sentenced to 10-25 years in prison 1999, but was released on parole on June 1, 2007; 4 years before his death on June 3, 2011.

- ^ Hall 1987, p.282

- ^ "Jonestown Audiotape Primary Project." Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University. Template:WebCite

- ^ "1978: Mass Suicide Leaves 900 Dead". Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945, Random House, 1970, p. 519

- ^ Suicide and Self-Starvation, Terence M. O'Keeffe, Philosophy, Vol. 59, No. 229 (Jul., 1984), pp. 349–363

- ^ Watson, Bruce (2007). Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- ^ Yisrael Gutman, Michael Berenbaum; Anatomy of the Auschwitz death camp, p. 400: Indiana University Press (1998) ISBN 0-253-20884-X

- ^ "Activist: Farmer suicides in India linked to debt, globalization". CNN. January 05, 2010

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Suicide: Data Sources

- ^ Teasdale TW, Engberg AW (2001). "Suicide after traumatic brain injury: a population study". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 71 (4): 436–40. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.4.436. PMC 1763534. PMID 11561024.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Simpson G, Tate R (2007). "Suicidality in people surviving a traumatic brain injury: prevalence, risk factors and implications for clinical management". Brain Inj. 21 (13–14): 1335–51. doi:10.1080/02699050701785542. PMID 18066936.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB (2003). "Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997". Am J Psychiatry. 160 (4): 765–72. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.765. PMID 12668367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Birtchnell J, Masters N (1989). "Poverty and depression". Practitioner. 233 (1474): 1141–6. PMID 2616460.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH (2001). "Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study". JAMA. 286 (24): 3089–96. PMID 11754674.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ^ Koch, Wendy (2007-07-03). "Study: Troubled homes better than foster care". Usatoday.Com. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ^ Lawrence, CR; Carlson, EA; Egeland, B (2006). "The impact of foster care on development". Development and Psychopathology. 18 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1017/S0954579406060044. PMID 16478552.

- ^ Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B (1985). "Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation". Am J Psychiatry. 142 (5): 559–63. PMID 3985195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC, Linton K, Prabhu F (2011). "The mediating effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relation between depressive symptoms and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults". Aging Ment Health. 15 (2): 214–20. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.501064. PMID 20967639.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stravynski A, Boyer R (2001). "Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: a population-wide study". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 31 (1): 32–40. PMID 11326767.

- ^ Vanderhorst RK, McLaren S (2005). "Social relationships as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in older adults". Aging Ment Health. 9 (6): 517–25. doi:10.1080/13607860500193062. PMID 16214699.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McLaren S, Gomez R, Bailey M, Van Der Horst RK (2007). "The association of depression and sense of belonging with suicidal ideation among older adults: applicability of resiliency models". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 37 (1): 89–102. doi:10.1521/suli.2007.37.1.89. PMID 17397283.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1168-a, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1168-ainstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.09.025, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.paid.2003.09.025instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1017/S0021932004006959, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1017/S0021932004006959instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/07481180600614591, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/07481180600614591instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2466/pms.109.3.718-720, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2466/pms.109.3.718-720instead. - ^ Only the bright commit suicide. Does a controversial theory linking intelligence with suicide rates help to explain why so many scientists kill themselves?

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2466/pr0.106.3.718-720, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2466/pr0.106.3.718-720instead. - ^ a b Michael Martin. "Religious Affiliation and Suicide Attempt". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

Religiously unaffiliated subjects had significantly more lifetime suicide attempts and more first-degree relatives who committed suicide than subjects who endorsed a religious affiliation. Unaffiliated subjects were younger, less often married, less often had children, and had less contact with family members. Furthermore, subjects with no religious affiliation perceived fewer reasons for living, particularly fewer moral objections to suicide. In terms of clinical characteristics, religiously unaffiliated subjects had more lifetime impulsivity, aggression, and past substance use disorder.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21142333, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21142333instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15950281, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15950281instead. - ^ Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, Valenstein M (2008). "Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 30 (6): 521–7. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.003. PMC 2601576. PMID 19061678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simpson GK, Tate RL (2007). "Preventing suicide after traumatic brain injury: implications for general practice". Med. J. Aust. 187 (4): 229–32. PMID 17708726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Teasdale TW, Engberg AW (2001). "Suicide after traumatic brain injury: a population study". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 71 (4): 436–40. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.4.436. PMC 1763534. PMID 11561024.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Druss B, Pincus H (2000). "Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses". Arch. Intern. Med. 160 (10): 1522–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522. PMID 10826468.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Braden JB, Sullivan MD (2008). "Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults with self-reported pain conditions in the national comorbidity survey replication". J Pain. 9 (12): 1106–15. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.004. PMC 2614911. PMID 19038772.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM; et al. (2011). "Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military". J Affect Disord. 136 (3): 743–50. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. PMID 22032872.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bernert RA, Joiner TE, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B (2005). "Suicidality and sleep disturbances". Sleep. 28 (9): 1135–41. PMID 16268383.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, Faillace LA, Stickney SK (1978). "Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1315–20. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350041003. PMID 568461.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morrison, James O. (1999). When Psychological Problems Mask Medical Disorders: A Guide for Psychotherapists. New York: The Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-539-8.

- ^ Rothbard AB; Blank MB; Staab JP; et al. (2009). "Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients". Psychiatr Serv. 60 (4): 534–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.534. PMID 19339330.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hall RC, Gardner ER, Stickney SK, LeCann AF, Popkin MK (1980). "Physical illness manifesting as psychiatric disease. II. Analysis of a state hospital inpatient population". Archives of General Psychiatry. 37 (9): 989–95. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220027002. PMID 7416911.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G (2004). "Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis" (Free full text). BMC Psychiatry. 4: 37. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-37. PMC 534107. PMID 15527502.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, Wasserman D (2004). "Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: revisiting the evidence". Crisis. 25 (4): 147–55. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147. PMID 15580849.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM (2005). "The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 62 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. PMID 15753237.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gliatto, Michael F. (1999). "Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Ideation". American Family Physician. 59 (6): 1500–6. PMID 10193592. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sharp LK, Lipsky MS (2002). "Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings". American family physician. 66 (6): 1001–8. PMID 12358212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Torzsa P, Szeifert L, Dunai K, Kalabay L, Novák M (2009). "A depresszió diagnosztikája és kezelése a családorvosi gyakorlatban". Orvosi Hetilap. 150 (36): 1684–93. doi:10.1556/OH.2009.28675. PMID 19709983.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "College Students Exhibiting More Severe Mental Illness, Study Finds". Apa.org. 2010-08-12. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Lambert KG (2006). "Rising rates of depression in today's society: Consideration of the roles of effort-based rewards and enhanced resilience in day-to-day functioning". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (4): 497–510. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.09.002. PMID 16253328.

- ^ World health Organization:Depression

- ^ Whitlock J, Knox KL (2007). "The relationship between self-injurious behavior and suicide in a young adult population". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (7): 634–40. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.7.634. PMID 17606825.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Rethink – About self harm".

- ^ a b Gelder, Mayou, Geddes (2005). Psychiatry: Page 170. New York, NY; Oxford University Press Inc.

- ^ Shaffer D (1988). "The epidemiology of teen suicide: an examination of risk factors". J Clin Psychiatry. 49 (Suppl): 36–41. PMID 3047106.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Krishnan, V.; Nestler, E. (2008). "The molecular neurobiology of depression". Nature. 455 (7215): 894–902. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..894K. doi:10.1038/nature07455. PMC 2721780. PMID 18923511.

- ^ Phillips J, Murray P, Kirk P., The biology of disease; pp.5-9 ISBN 978-0-632-05404-6

- ^ David M. Stoff, Elizabeth J. Susman: Developmental psychobiology of aggression; Cambridge University Press (2005) ISBN 0-521-82601-2

- ^ S. Hossein Fatemi, Paula J. Clayton:The medical basis of psychiatry. p.562 Springer(1994);, ISBN 978-1-58829-917-8

- ^ J. John Mann, M.D., Neurobiological Aspects of Suicide

- ^ Roberto Tatarelli, Maurizio Pompili, Paolo Girardi: Suicide in psychiatric disorders. p.266; Nova Science Pub Inc;(2007) ISBN 1-60021-738-9

- ^ Alan F. Schatzberg: The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders. p.489; American Psychiatric Publishing; (2005) ISBN 1-58562-151-X

- ^ Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V (2001). "The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: a focus on the serotonergic system". Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (5): 467–77. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00228-1. PMID 11282247.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brezo J, Klempan T, Turecki G (2008). "The genetics of suicide: a critical review of molecular studies". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 31 (2): 179–203. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.008. PMID 18439443.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Goldsmith, Sara K. (2002). Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-309-08321-4.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 271079606, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=271079606instead. - ^ Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2002). "Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: nested case-control study". BMJ. 325 (7355): 74. PMC 117126. PMID 12114236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB (2002). "Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case-control study based on longitudinal registers". Lancet. 360 (9340): 1126–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11197-4. PMID 12387960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krishnan, V.; Nestler, E. (2009). "Epigenetics in Suicide and Depression". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (9): 812–813. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.033. PMC 2770810. PMID 19833253.

- ^ Trygve Tollefsbol: Handbook of Epigenetics: The New Molecular and Medical Genetics. p.562: Elsevier Science;(2010);ISBN 0-12-375709-6

- ^ Arturas Petronis: Brain, Behavior and Epigenetics, p.61 Springer (2011);ISBN 3-642-17425-6

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070320, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070320instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1037/a0018413, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1037/a0018413instead. - ^ D., PhD Frank, Jerome; Levin, Jerome D; S., PhD Piccirilli, Richard; Perrotto, Richard S; Culkin, Joseph (28 Sep 2001). Introduction to chemical dependency counseling. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-7657-0289-0.

- ^ Giner L, Carballo JJ, Guija JA; et al. (2007). "Psychological autopsy studies: the role of alcohol use in adolescent and young adult suicides". Int J Adolesc Med Health. 19 (1): 99–113. PMID 17458329.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fadem, Barbara (1 Dec 2003). Behavioral science in medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7817-3669-5.

- ^ a b Miller, NS; Mahler, JC; Gold, MS (1991). "Suicide risk associated with drug and alcohol dependence". Journal of addictive diseases. 10 (3): 49–61. doi:10.1300/J069v10n03_06. PMID 1932152.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15950281, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15950281instead. - ^ a b O'Donohue, William T.; R. Byrd, Michelle; Cummings, Nicholas A.; Henderson, Deborah P. (2005). Behavioral integrative care: treatments that work in the primary care setting. New York: Brunner-Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-415-94946-0.

- ^ a b Ayd, Frank J (31 May 2000). Lexicon of psychiatry, neurology, and the neurosciences. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Williams Wilkins. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- ^ Darke, S.; Kaye, S.; McKetin, R.; Duflou, J. (2008). "Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use". Drug Alcohol Rev. 27 (3): 253–62. doi:10.1080/09595230801923702. PMID 18368606.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Darke S, Ross J (2002). "Suicide among heroin users: rates, risk factors and methods". Addiction. 97 (11): 1383–94. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00214.x. PMID 12410779.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Teesson M, Havard A, Fairbairn S, Ross J, Lynskey M, Darke S (2005). "Depression among entrants to treatment for heroin dependence in the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS): prevalence, correlates and treatment seeking". Drug Alcohol Depend. 78 (3): 309–15. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.001. PMID 15893162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Professor C Heather Ashton (1987). "Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: Outcome in 50 Patients". British Journal of Addiction. 82: 655–671.

- ^ Neutel CI, Patten SB (1997). "Risk of suicide attempts after benzodiazepine and/or antidepressant use". Ann Epidemiol. 7 (8): 568–74. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00126-9. PMID 9408553.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Taiminen TJ (1993). "Effect of psychopharmacotherapy on suicide risk in psychiatric inpatients". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 87 (1): 45–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03328.x. PMID 8093823.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brent DA; Emslie GJ; Clarke GN; et al. (2009). "Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study". Am J Psychiatry. 166 (4): 418–26. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070976. PMID 19223438.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Allgulander C, Borg S, Vikander B (1984). "A 4–6-year follow-up of 50 patients with primary dependence on sedative and hypnotic drugs". Am J Psychiatry. 141 (12): 1580–2. PMID 6507663.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wines JD, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH (2004). "Suicidal behavior, drug use and depressive symptoms after detoxification: a 2-year prospective study". Drug Alcohol Depend. 76 (Suppl): S21–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.004. PMID 15555813.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allgulander C, Ljungberg L, Fisher LD (1987). "Long-term prognosis in addiction on sedative and hypnotic drugs analyzed with the Cox regression model". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 75 (5): 521–31. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02828.x. PMID 3604738.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Colvin, Rod (26 August 2008). Overcoming Prescription Drug Addiction: A Guide to Coping and Understanding (3 ed.). United States of America: Addicus Books. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-1-886039-88-9.

I have treated ten thousand patients for alcohol and drug problems and have detoxed approximately 1,500 patients for benzodiazepines – the detox for the benzodiazepines is one of the hardest detoxes we do. It can take an extremely long time, about half the length of time they have been addicted – the ongoing relentless withdrawals can be so incapacitating it can cause total destruction to one's life – marriages break up, businesses are lost, bankruptcy, hospitalization, and of course suicide is probably the most single serious side effect.

- ^ Iwasaki M, Akechi T, Uchitomi Y, Tsugane S (2005). "Cigarette Smoking and Completed Suicide among Middle-aged Men: A Population-based Cohort Study in Japan". Annals of Epidemiology. 15 (4): 286–92. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.08.011. PMID 15780776.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller M, Hemenway D, Rimm E (2000). "Cigarettes and suicide: a prospective study of 50,000 men". American journal of public health. 90 (5): 768–73. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.5.768. PMC 1446219. PMID 10800427.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hemenway D, Solnick SJ, Colditz GA (1993). "Smoking and suicide among nurses". American journal of public health. 83 (2): 249–51. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.2.249. PMC 1694571. PMID 8427332.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thomas Bronischa, Michael Höflerab, Roselind Liebac (2008). "Smoking predicts suicidality: Findings from a prospective community study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 108 (1): 135–145. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.010. PMID 18023879.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller M, Hemenway D, Bell NS, Yore MM, Amoroso PJ (2000). "Cigarette smoking and suicide: a prospective study of 300,000 male active-duty Army soldiers". American Journal of Epidemiology. 151 (11): 1060–3. PMID 10873129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chignon JM, Cortes MJ, Martin P, Chabannes JP (1998). "[Attempted suicide and alcohol dependence: results of an epidemiologic survey]". Encephale (in French). 24 (4): 347–54. PMID 9809240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ (2009). "Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 66 (3): 260–6. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. PMID 19255375.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moreyra, P., Ibanez A., Saiz-Ruiz J., Nissenson K., Blanco C. (2000). "Review of the phenomenology, etiology and treatment of pathological gambling". German Journal of Psychiatry. 3: 37–52.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pallanti, Stefano; Rossi, Nicolò Baldini; Hollander, Eric (2006). "11. Pathological Gambling". In Hollander, Eric; Stein, Dan J. (eds.). Clinical manual of impulse-control disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 251–289. ISBN 978-1-58562-136-1.

- ^ Volberg, R.A. (2002). "The epidemiology of pathological gambling". Psychiatric Annals. 32: 171–8.

- ^ Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Jadamec A (2002). "Gambling behavior in adolescent substance abuse". Subst Abus. 23 (3): 191–8. doi:10.1080/08897070209511489. PMID 12444352.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kausch O (2003). "Suicide attempts among veterans seeking treatment for pathological gambling". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (9): 1031–8. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0908. PMID 14628978.

- ^ Kausch O (2003). "Patterns of substance abuse among treatment-seeking pathological gamblers". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 25 (4): 263–70. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00117-X. PMID 14693255.

- ^ Ladd, G. T., Petry N. M. (2003) A comparison of pathological gamblers with and without substance abuse treatment histories. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, 202-9.

- ^ Hagan, Kate (2010-04-21). "Gambling linked to one in five suicidal patients". Melbourne: Theage.com.au. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Niederkrotenthaler T, Herberth A, Sonneck G (2007). "[The "Werther-effect": legend or reality?]". Neuropsychiatr (in German). 21 (4): 284–90. PMID 18082110.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stack S (2003). "Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide". J Epidemiol Community Health. 57 (4): 238–40. doi:10.1136/jech.57.4.238. PMC 1732435. PMID 12646535.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ O'Carroll PW, Potter LB (1994). "Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: recommendations from a national workshop. United States Department of Health and Human Services". MMWR Recomm Rep. 43 (RR–6): 9–17. PMID 8015544.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thomas H. Ollendick, Carolyn S. Schroeder: Encyclopedia of clinical child and pediatric psychology, p.61; Springer;(2003) ISBN 0-306-47490-5

- ^ Marion Crook: Out of the darkness: teens and suicide p.56 Arsenal Pulp Press (2004) ISBN 1-55152-141-5

- ^ Stack S (2005). "Suicide in the media: a quantitative review of studies based on non-fictional stories". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 35 (2): 121–33. doi:10.1521/suli.35.2.121.62877. PMID 15843330.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pirkis J (July 2009). 72X "Suicide and non-fatal self-harm". Psychiatry. 8 (7): 269–271. doi:10.1016/j.mppsy.2009.04.009.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Niederkrotenthaler T; Voracek M; Herberth A; et al. (2010). "Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects". Br J Psychiatry. 197 (3): 234–43. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633. PMID 20807970.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ajdacic-Gross V; Weiss MG; Ring M; et al. (2008). "Methods of suicide: international suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database". Bull. World Health Organ. 86 (9): 726–32. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.043489. PMC 2649482. PMID 18797649.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ajdacic-Gross, Vladeta, et al. Template:PDFlink. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (9): 726–732. September 2008. Accessed 2 August 2011. Archived 2 August 2011. See html version.

- The data can be seen here.

- ^ O'Connor, Rory C.; Platt, Stephen; Gordon, Jacki, eds. (1 June 2011). International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice. John Wiley and Sons. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-119-99856-3.

- ^ Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F (2007). "The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review". BMC Public Health. 7: 357. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-357. PMC 2262093. PMID 18154668.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "U.S. Suicide Statistics (2005)". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "UpToDate Inc".

- ^ Brent DA, Moritz G, Bridge J, Perper J, Canobbio R (1996). "Long-term impact of exposure to suicide: a three-year controlled follow-up". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 35 (5): 646–53. doi:10.1097/00004583-199605000-00020. PMID 8935212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Phillips DP, Carstensen LL (1986). "Clustering of teenage suicides after television news stories about suicide". N. Engl. J. Med. 315 (11): 685–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198609113151106. PMID 3748072.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ World Health Organization: Suicide prevention (SUPRE)

- ^ Sakinofsky, I (2007 Jun). "The current evidence base for the clinical care of suicidal patients: strengths and weaknesses". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 52 (6 Suppl 1): 7S–20S. PMID 17824349.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Suicide". The United States Surgeon General. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ Best Practices Registry (BPR) For Suicide Prevention

- ^ Rodgers PL, Sudak HS, Silverman MM, Litts DA (2007). "Evidence-based practices project for suicide prevention". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 37 (2): 154–64. doi:10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.154. PMID 17521269.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Giannini, A. James; Slaby, Andrew Edmund; Giannini, Matthew C. (1982). Handbook of overdose and detoxification emergencies. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: Medical Examination Pub. Co. ISBN 0-87488-182-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Office of the Surgeon General:The Surgeon General's Call To Action To Prevent Suicide 1999 [1]

- ^ Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon: International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p. 510 [2]

- ^ Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon, International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p.361; Wiley-Blackwell (2011), ISBN 0-470-68384-8

- ^ Alan F. Schatzberg: The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders, p. 503: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2005) ISBN 1-58562-151-X

- ^ Crawford, MJ (2011 May). "Impact of screening for risk of suicide: randomised controlled trial". The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 198 (5): 379–84. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083592. PMID 21525521.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Depression and Suicide Andrew B. Medscape

- ^ González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW (2010). "Depression Care in the United States: Too Little for Too Few". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. PMC 2887749. PMID 20048221.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL (2002). "Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (6): 909–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. PMID 12042175.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee HC, Lin HC, Liu TC, Lin SY (2008). "Contact of mental and nonmental health care providers prior to suicide in Taiwan: a population-based study". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (6): 377–83. PMID 18616858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pirkis J, Burgess P (1998). "Suicide and recency of health care contacts. A systematic review". The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 173 (6): 462–74. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.6.462. PMID 9926074.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Randolph B. Schiffer, Stephen M. Rao, Barry S. Fogel, Neuropsychiatry: Neuropsychiatry of suicide, pp. 706-713, (2003)ISBN 0781726557

- ^ Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, Geddes JR (2005). "Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials". Am J Psychiatry. 162 (10): 1805–19. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1805. PMID 16199826.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM; et al. (2006). "Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 63 (7): 757–66. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. PMID 16818865.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, Faillace LA, Stickney SK (1978). "Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1315–20. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350041003. PMID 568461.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chuang L., Mental Disorders Secondary to General Medical Conditions; Medscape;2011 [3]

- ^ Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D (1996). "Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review". Psychiatr Serv. 47 (12): 1356–63. PMID 9117475.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kamboj MK, Tareen RS (2011). "Management of nonpsychiatric medical conditions presenting with psychiatric manifestations". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 58 (1): 219–41, xii. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.10.008. PMID 21281858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Andreas P. Otte, Kurt Audenaert, Kathelijne Peremans, Nuclear medicine in psychiatry: Functional imaging of Suicidal Behavior, pp.475-483, Springer (2004);ISBN 3-540-00683-4

- ^ Patricia D. Barry, Suzette Farmer; Mental health & mental illness,p.282, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;(2002) ISBN 0-7817-3138-0

- ^ Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J (2003). "Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 Suppl 5: 44–52. PMID 12720484.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coppen A (2000). "Lithium in unipolar depression and the prevention of suicide". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 9: 52–6. PMID 10826662.

- ^ Canadian Agency for Drugs nd technology in Health: Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in Adolescents for Suicide Prevention: Systematic Review of Clinical-Effectiveness, CADTH Technology Overviews, Volume 1, Issue 1, March 2010 [4]

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health: Suicide in the U.S.: Statistics and Prevention [5]

- ^ Stanley B; Brown G; Brent DA; et al. (2009). "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 48 (10): 1005–13. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbfe. PMC 2888910. PMID 19730273.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ "Suicide prevention". WHO Sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. February 16, 2006. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ "2007 Data" (PDF). Suicide Prevention. Suicidology.org. 2007. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2006). "Homicides and suicides—National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2003–2004". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (26): 721–4. PMID 16826158.