The Cloisters

View of the main entrance | |

| Established | May 10, 1938 |

|---|---|

| Location | 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tryon Park Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°51′53″N 73°55′55″W / 40.8648°N 73.9319°W |

| Type | Medieval art Romanesque architecture Gothic architecture |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: Bx7, M4, M100 |

| Website | www |

The Cloisters | |

New York City Landmark No. 0835

| |

| Built | 1935–1939 |

| Architect | Charles Collens |

| Part of | Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters (ID78001870) |

| NYCL No. | 0835 |

| Significant dates | |

| Designated CP | December 19, 1978[2] |

| Designated NYCL | March 19, 1974[1] |

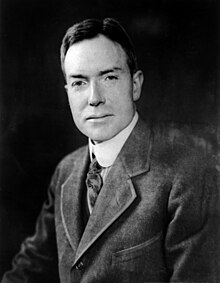

The Cloisters, also known as the Met Cloisters, is a museum in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, New York City. The museum, situated in Fort Tryon Park, specializes in European medieval art and architecture, with a focus on the Romanesque and Gothic periods. Governed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it contains a large collection of medieval artworks shown in the architectural settings of French monasteries and abbeys. Its buildings are centered around four cloisters—the Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem, Bonnefont and Trie—that were acquired by American sculptor and art dealer George Grey Barnard in France before 1913, and moved to New York. Barnard's collection was bought for the museum by financier and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. Other major sources of objects were the collections of J. P. Morgan and Joseph Brummer.

The museum's building was designed by the architect Charles Collens, on a site on a steep hill, with upper and lower levels. It contains medieval gardens and a series of chapels and themed galleries, including the Romanesque, Fuentidueña, Unicorn, Spanish, and Gothic rooms.[3] The design, layout, and ambiance of the building are intended to evoke a sense of medieval European monastic life.[4] It holds about 5,000 works of art and architecture, all European and mostly dating from the Byzantine to the early Renaissance periods, mainly during the 12th through 15th centuries. The objects include stone and wood sculptures, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings, of which the best known include the c. 1422 Early Netherlandish Mérode Altarpiece and the c. 1495–1505 Flemish Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries.

Rockefeller purchased the museum site in Washington Heights in 1930 and donated it to the Metropolitan in 1931. Upon its opening on May 10, 1938, the Cloisters was described as a collection "shown informally in a picturesque setting, which stimulates imagination and creates a receptive mood for enjoyment".[5]

History

[edit]Formation

[edit]The basis for the museum's architectural structure came from the collection of George Grey Barnard, an American sculptor and collector who almost single-handedly established a medieval art museum near his home in the Fort Washington section of Upper Manhattan. Although he was a successful sculptor who had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, his income was not enough to support his family. Barnard was a risk taker and led most of his life on the edge of poverty.[6] He moved to Paris in 1883 where he studied at the Académie des Beaux-Arts.[6] He lived in the village of Moret-sur-Loing, near Fontainebleau, between 1905 and 1913,[7] and began to deal in 13th- and 14th-century European objects to supplement his earnings. In the process he built a large personal collection of what he described as "antiques", at first by buying and selling stand-alone objects with French dealers,[8] then by the acquisition of in situ architectural artifacts from local farmers.[6]

Barnard was primarily interested in the abbeys and churches founded by monastic orders from the 12th century. Following centuries of pillage and destruction during wars and revolutions, stones from many of these buildings were reused by local populations.[6] A pioneer in seeing the value in such artifacts, Barnard often met with hostility to his effort from local and governmental groups.[7] Yet he was an astute negotiator who had the advantage of a professional sculptor's eye for superior stone carving, and by 1907 he had built a high-quality collection at relatively low cost. Reputedly he paid $25,000 for the Trie buildings, $25,000 for the Bonnefort and $100,000 for the Cuxa cloisters.[9] His success led him to adopt a somewhat romantic view of himself. He recalled bicycling across the French countryside and unearthing fallen and long-forgotten Gothic masterworks along the way. He claimed to have found the tomb effigy of Jean d'Alluye face down, in use as a bridge over a small stream.[8] By 1914 he had gathered enough artifacts to open a gallery in Manhattan.[10]

Barnard often neglected his personal finances,[9] and was so disorganized that he often misplaced the origin or provenance of his purchases. He sold his collection to John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1925 during one of his recurring monetary crises.[11] The two had been introduced by the architect William W. Bosworth.[12] Purchased for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the acquisition included structures that would become the foundation and core of the museum.[6][7] Rockefeller and Barnard were polar opposites in both temperament and outlook and did not get along; Rockefeller was reserved, Barnard exuberant. The English painter and art critic Roger Fry was then the Metropolitan's chief European acquisition agent and acted as an intermediary.[13] Rockefeller eventually acquired Barnard's collection for around $700,000, retaining Barnard as an advisor.[14]

In 1927 Rockefeller hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of one of the designers of Central Park, and the Olmsted Brothers firm to create a park in the Fort Washington area.[15] In February 1930 Rockefeller offered to build the Cloisters for the Metropolitan.[16] Under consultation with Bosworth,[7] he decided to build the museum at a 66.5-acre (26.9 ha) site at Fort Tryon Park, which they chose for its elevation, views, and accessible but isolated location.[10] The land and existing buildings were purchased that year from the C. K. G. Billings estate and other holdings in the Fort Washington area. The Cloisters building and adjacent 4-acre (1.6 ha) gardens were designed by Charles Collens.[17] They incorporate elements from abbeys in Catalonia and France. Parts from Sant Miquel de Cuixà, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Bonnefont-en-Comminges, Trie-sur-Baïse and Froville were disassembled stone-by-stone and shipped to New York City, where they were reconstructed and integrated into a cohesive whole. Construction took place over a five-year period from 1934.[18] In 1933, Rockefeller donated several hundred acres of the New Jersey Palisades clifftops across the river, which he had purchased over several years for the Palisades Interstate Park Commission to preserve the land from further development.[19][20] The Cloisters' new building and gardens were officially opened on May 10, 1938,[21] though the public was not allowed to visit until four days later.[22]

Early acquisitions

[edit]

Rockefeller financed the purchase of many of the early collection of works, often buying independently and then donating the items to the museum.[5] His financing of the museum has led to it being described as "perhaps the supreme example of curatorial genius working in exquisite harmony with vast wealth".[6] The second major donor was the industrialist J. P. Morgan, founder of the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, who spent the last 20 years of his life acquiring artworks, "on an imperial scale" according to art historian Jean Strous,[23] spending some $900 million (inflation adjusted) in total. After his death, his son J. P. Morgan Jr. donated a large number of works from the collection to the Metropolitan.[24]

A further major early source of objects was the art dealer Joseph Brummer (1883–1947), long a friend of a curator at the Cloisters, James Rorimer. Rorimer had long recognized the importance of Brummer's collection, and purchased large quantities of objects in the months after Brummer's sudden death in 1947. According to Christine E. Brennan of the Metropolitan, Rorimer realized that the collection offered works that could rival the Morgan Collection in the Metropolitan's Main Building, and that "the decision to form a treasury at The Cloisters was reached... because it had been the only opportunity since the late 1920s to enrich the collection with so many liturgical and secular objects of such high quality."[25] These pieces, including works in gold, silver, and ivory, are today held in the Treasury room of the Cloisters.[25]

Collection

[edit]The museum's collection of artworks consists of about 5,000 pieces. They are displayed across a series of rooms and spaces, mostly separate from those dedicated to the installed architectural artifacts. The Cloisters has never focused on building a collection of masterpieces; rather, the objects are chosen thematically yet arranged simply to enhance the atmosphere created by the architectural elements in the particular setting or room in which they are placed.[5] To create the atmosphere of a functioning series of cloisters, many of the individual works, including capitals, doorways, stained glass, and windows are placed within the architectural elements themselves.[26]

Panel paintings and sculpture

[edit]

The museum's best-known panel painting is Robert Campin's c. 1425–28 Mérode Altarpiece, a foundational work in the development of Early Netherlandish painting,[27] which has been at The Cloisters since 1956. Its acquisition was funded by Rockefeller and described at the time as a "major event for the history of collecting in the United States".[28] The triptych is well preserved with little overpainting, glossing, dirt layers or paint loss.[29] Other panel paintings in the collection include a Nativity triptych altarpiece attributed to a follower of Rogier van der Weyden,[30] and the Jumieges panels by an unknown French master.[31]

The 12th-century English walrus ivory Cloisters Cross contains more than 92 intricately carved figures and 98 inscriptions. A similar 12th-century French metalwork reliquary cross contains six sequences of engravings on either side of its shaft, and across the four sides of its lower arms.[32] Further pieces of note include a 13th-century English Enthroned Virgin and Child statuette,[33] a c. 1490 German statue of Saint Barbara,[34] and an early 16th-century boxwood Miniature Altarpiece with the Crucifixion.[35] Other significant works include fountains and baptismal fonts, chairs,[36] aquamaniles (water containers in animal or human form), bronze lavers, alms boxes and playing cards.[37]

The museum has an extensive collection of medieval European frescoes, ivory statuettes, reliquary wood and metal shrines and crosses, as well as examples of the very rare Gothic boxwood miniatures.[38] It has liturgical metalwork vessels and rare pieces of Gothic furniture and metalwork.[39] Many pieces are not associated with a particular architectural setting, so their placement in the museum may vary.[40] Some of the objects have dramatic provenance, including those plundered from the estates of aristocrats during the French Revolutionary Army's occupation of the Southern Netherlands.[41] The Unicorn tapestries were for a period used by the French army to cover potatoes and keep them from freezing.[42] The set was purchased by Rockefeller in 1922, and six of the tapestries hung in his New York home until they were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1938.[43]

Illuminated manuscripts

[edit]

The museum's collection of illuminated books is small but of exceptional quality. J.P. Morgan was a major early donor, but although his taste leaned heavily towards rare printed and illuminated books,[44] he donated very few to the Metropolitan, instead preserving them at the Morgan Library.[24] At the same time, the consensus within the Met was that the Cloisters should focus on architectural elements, sculpture and decorative arts to enhance the environmental quality of the institution, whereas manuscripts were considered more suited to the Morgan Library in lower Manhattan.[45] The Cloisters' books are today displayed in the Treasury room, and include the French "Cloisters Apocalypse" (or "Book of Revelation", c. 1330, probably Normandy),[46] Jean Pucelle's "Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux" (c. 1324–28), the "Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg", attributed to Jean Le Noir and the "Belles Heures du Duc de Berry" (c. 1399–1416) attributed to the Limbourg brothers.[47] In 2015 the Cloisters acquired a small Netherlandish Book of Hours illuminated by Simon Bening.[48] Each is of exceptional quality, and their acquisition was a significant achievement for the museum's early collectors.[45]

A coat of arms illustrated on one of the leaves of the "Cloisters Apocalypse" suggests it was commissioned by a member of the de Montigny family of Coutances, Normandy.[49] Stylistically it resembles other Norman illuminated books, as well as some designs on stained glass, of the period.[50] The book was in Switzerland by 1368, possibly at the abbey of Zofingen, in the canton of Aargau. It was acquired by the Met in 1968.[51]

The "Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux" is a very small early Gothic book of hours containing 209 folios, of which 25 are full-page miniatures. It is lavishly decorated in grisaille drawings, historiated initials and almost 700 border images. Jeanne d'Évreux was the third wife of Charles IV of France, and after their deaths the book went into the possession of Charles' brother, Jean, duc de Berry. The use of grisaille (shades of gray) drawings allowed the artist to give the figures a highly sculptural form,[52] and the miniatures contain structures typical of French Gothic architecture of the period. The book has been described as "the high point of Parisian court painting", and evidence of "the unprecedentedly refined artistic tastes of the time".[53]

The "Belles Heures" is widely regarded as one of the finest extant examples of manuscript illumination, and very few books of hours are as richly decorated. It is the only surviving complete book attributed to the Limbourg brothers.[54] Rockefeller purchased the book from Maurice de Rothschild in 1954, and donated it to the Metropolitan.[55]

The very small "Bonne de Luxembourg" manuscript (each leaf 12.5 × 8.4 × 3.9 cm) is attributed to Jean le Noir, and noted for its preoccupation with death. It was commissioned for Bonne de Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, daughter of John the Blind and the wife of John II of France, probably at the end of her husband's life, c. 1348–49. It was in a private collection for many years and thus known only through poor-quality photographic reproductions until acquired by the museum in 1969. Produced in tempera, grisaille, ink, and gold leaf on vellum, it had been rarely studied and was, until that point, misattributed to Jean Pucelle. Following its acquisition, it was studied by art historians, after which attribution was given to Le Noir.[56]

Tapestries

[edit]

While examples of textile art are displayed throughout the museum, there are two dedicated rooms given to individual series of tapestries, the South Netherlandish Nine Heroes (c. 1385)[57] and Flemish The Hunt of the Unicorn (c. 1500).[58] The Nine Heroes room is entered from the Cuxa cloisters.[57] Its 14th-century tapestries are among the earliest surviving examples of tapestry, and are thought to be the original versions following widely influential and copied designs attributed to Nicolas Bataille. They were acquired over twenty years, involving the purchase of more than 20 fragments which were then sewn together during a long reassembly process. The chivalric figures represent the scriptural and legendary Nine Worthies, who consist of three pagans (Hector, Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar), three Jews (Joshua, David and Judas Maccabeus) and three Christians (King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon). Of these, five figures survive: Hector, Caesar, Joshua, David and Arthur.[59] They have been described as representing "in their variety, the highest level of a rich and powerful social structure of later fourteenth-century France".[60]

The Hunt of the Unicorn room can be entered from the hall containing the Nine Heroes via an early 16th-century door carved with representations of unicorns.[61] The unicorn tapestries consist of a series of large, colourful hangings and fragment textiles[62] designed in Paris[59] and woven in Brussels or Liège. Noted for their vivid colourization—dominated by blue, yellow-brown, red, and gold hues—and the abundance of a wide variety of flora,[63] they were produced for Anne of Brittany and completed c. 1495–1505.[64] The tapestries were purchased by Rockefeller in 1922 for about one million dollars, and donated to the museum in 1937.[65] They were cleaned and restored in 1998, and are now hung in a dedicated room on the museum's upper floor.[66]

The large "Nativity" panel (also known as "Christ is Born as Man's Redeemer") from c. 1500, South Netherlandish (probably in Brussels), Burgos Tapestry was acquired by the museum in 1938. It was originally one of a series of eight tapestries representing the salvation of man,[67] with individual scenes influenced by identifiable panel paintings, including by van der Weyden.[68] It was badly damaged in earlier centuries: it had been cut into several irregular pieces and undergone several poor-quality restorations. The panel underwent a long restoration from 1971, undertaken by Tina Kane and Alice Blohm of the Metropolitan's Department of Textile Conservation. It is today hung in the Late Gothic hall.[69]

Stained glass

[edit]

The Cloisters' collection of stained glass consists of around three hundred panels, generally French and Germanic and mostly from the 13th to early 16th centuries.[71] A number were formed from handmade opalescent glass. Works in the collection are characterized by vivid colors and often abstract designs and patterns; many have a devotional image as a centerpiece.[72] The majority of these works are in the museum's Boppard room, named after the Carmelite church of Saint Severinus in Boppard, near Koblenz, Germany.[10] The collection's pot-metal works (from the High Gothic period) highlight the effects of light,[73] especially the transitions between darkness, shadow and illumination.[74] The Met's collection grew in the early 20th century when Raymond Picairn made acquisitions at a time when medieval glass was not highly regarded by connoisseurs, and was difficult to extract and transport.[75]

Jane Hayward, a curator at the museum from 1969 who began the museum's second phase of acquisition, describes stained glass as "unquestioningly the preeminent form of Gothic medieval monumental painting".[76] She bought c. 1500 heraldic windows from the Rhineland, now in the Campin room with the Mérode Altarpiece. Hayward's addition in 1980 led to a redesign of the room so that the installed pieces would echo the domestic setting of the altarpiece. She wrote that the Campin room is the only gallery in the Met "where domestic rather than religious art predominates...a conscious effort has been made to create a fifteenth-century domestic interior similar to the one shown in [Campin's] Annunciation panel."[77]

Other significant acquisitions include late 13th-century grisaille panels from the Château de Bouvreuil in Rouen, glass work from the Cathedral of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais at Sées,[77] and panels from the Acezat collection, now in the Heroes Tapestry Hall.[78]

Exterior

[edit]

The building is set into a steep hill, and thus the rooms and halls are divided between an upper entrance and a ground-floor level. The enclosing exterior building is mostly modern, and is influenced by and contains elements from the 13th-century church at Saint-Geraud at Monsempron, France, from which the northeast end of the building borrows especially. It was mostly designed by the architect Charles Collens, who took influence from works in Barnard's collection. Rockefeller closely managed both the building's design and construction, which sometimes frustrated the architects and builders.[79]

The building contains architecture elements and settings taken mostly from four French abbeys, which between 1934 and 1939 were transported, reconstructed, and integrated with new buildings in a project overseen by Collins. He told Rockefeller that the new building "should present a well-studied outline done in the very simplest form of stonework growing naturally out of the rocky hill-top. After looking through the books in the Boston Athenaeum ... we found a building at Monsempron in Southern France of a type which would lend itself in a very satisfactory manner to such a treatment."[79]

The architects sought to both memorialize the north hill's role in the American Revolution and to provide a sweeping view over the Hudson River. Construction of the exterior began in 1935. The stonework, primarily of limestone and granite from several European sources,[80] includes four Gothic windows from the refectory at Sens and nine arcades.[81] The dome of the Fuentidueña Chapel was especially difficult to fit into the planned area.[82] The east elevation, mostly of limestone, contains nine arcades from the Benedictine priory at Froville and four flamboyant French Gothic windows from the Dominican monastery at Sens, Burgundy.[81]

Cloisters

[edit]Cuxa

[edit]

Located on the south side of the building's main level, the Cuxa cloisters are the museum's centerpiece both structurally and thematically.[73] They were originally erected at the Benedictine Abbey of Sant Miquel de Cuixà on Mount Canigou, in the northeast Spanish Pyrenees, which was founded in 878.[83] The monastery was abandoned in 1791 and fell into disrepair; its roof collapsed in 1835 and its bell tower fell in 1839.[84] About half of its stonework was moved to New York between 1906 and 1907.[83][85] The installation became one of the first major undertakings by the Metropolitan after it acquired Barnard's collection. After intensive work over the fall and winter of 1925–26, the Cuxa cloisters were opened to the public on April 1, 1926.[86][5]

The quadrangle-shaped garden once formed a center around which monks slept in cells. The original garden seemed to have been lined by walkways around adjoining arches lined with capitals enclosing the garth. [87] It is impossible now to represent solely medieval species and arrangements; those in the Cuxa garden are approximations by botanists specializing in medieval history.[87] The oldest plan of the original building describes lilies and roses.[87] Although the walls are modern, the capitals and columns are original and cut from pink Languedoc marble from the Pyrenees.[86] The intersection of the two walkways contains an eight-sided fountain.[88]

The capitals were carved at different points in the abbey's history and thus contain a variety of forms and abstract geometric patterns, including scrolling leaves, pine cones, sacred figures such as Christ, the Apostles, angels, and monstrous creatures including two-headed animals, lions restrained by apes, mythic hybrids, a mermaid and inhuman mouths consuming human torsos.[89][90] The motifs are derived from popular fables,[83] or represent the brute forces of nature or evil,[91] or are based on late 11th- and 12th-century monastic writings, such as those by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153).[92] The order in which the capitals were originally placed is unknown, making their interpretation especially difficult, although a sequential and continuous narrative was probably not intended.[93] According to art historian Thomas Dale, to the monks, the "human figures, beasts, and monsters" may have represented the "tension between the world and the cloister, the struggle to repress the natural inclinations of the body".[94]

Saint-Guilhem

[edit]

The Saint-Guilhem cloisters were taken from the site of the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, and date from 804 AD to the 1660s.[95] Their acquisition around 1906 was one of Barnard's early purchases. The transfer to New York involved the movement of around 140 pieces, including capitals, columns and pilasters.[9] The carvings on the marble piers and column shafts recall Roman sculpture and are coiled by extravagant foliage, including vines.[96] The capitals contain acanthus leaves and grotesque heads peering out,[97] including figures at the Presentation at the Temple, Daniel in the Lions' Den[98] and the Mouth of Hell,[99] and several pilasters and columns.[95] The carvings seem preoccupied with the evils of hell. Those beside the mouth of hell contain representations of the devil and tormenting beasts, with, according to Young, "animal-like body parts and cloven hoofs [as they] herd naked sinners in chains to be thrown into an upturned monster's mouth".[100]

The Guilhem cloisters are inside the museum's upper level and are much smaller than originally built.[101] Its garden contains a central fountain[102] and plants potted in ornate containers, including a 15th-century glazed earthenware vase. The area is covered by a skylight and plate glass panels that conserve heat in the winter months. Rockefeller had initially wanted a high roof and clerestory windows, but was convinced by Joseph Breck, curator of decorative arts at the Metropolitan, to install a skylight. Breck wrote to Rockefeller that "by substituting a skylight for a solid ceiling ... the sculpture is properly illuminated, since the light falls in a natural way; the visitor has the sense of being in the open; and his attention, consequently, is not attracted to the modern superstructure."[103]

Bonnefont

[edit]

The Bonnefont cloisters were assembled from several French monasteries, but mostly come from a late 12th-century Cistercian Abbaye de Bonnefont at Bonnefont-en-Comminges, southwest of Toulouse.[104] The abbey was intact until at least 1807, and by the 1850s all of its architectural features had been removed from the site, often for decoration of nearby buildings.[105] Barnard purchased the stonework in 1937.[106] Today the Bonnefont cloisters contain 21 double capitals, and surround a garden that contains many features typical of the medieval period, including a central wellhead, raised flower beds and lined with wattle fences.[107] The marbles are highly ornate and decorated, some with grotesque figures.[108] The inner garden has been set with a medlar tree of the type found in The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, and is centered around a wellhead placed at Bonnefont-en-Comminges in the 12th century.[109] The Bonnefont is on the upper level of the museum and gives a view of the Hudson River and the cliffs of the Palisades.[10]

Trie

[edit]

The Trie cloisters was compiled from two late 15th- to early 16th-century French structures.[111] Most of its components came from the Carmelite convent at Trie-sur-Baïse in south-western France, whose original abbey, except for the church, was destroyed by Huguenots in 1571.[112] Small narrow buttresses were added in New York during the 1950s by Breck.[82] The rectangular garden hosts around 80 species of plants and contains a tall limestone cascade fountain at its center.[113] Like those from Saint-Guilhem, the Trie cloisters have been given modern roofing.[114]

The convent at Trie-sur-Baïse featured some 80 white marble capitals[115] carved between 1484 and 1490.[111] Eighteen were moved to New York and contain numerous biblical scenes and incidents from the lives of saints. Several of the carvings are secular, including those of legendary figures such as Saint George and the Dragon,[115] the "wild man" confronting a grotesque monster, and a grotesque head wearing an unusual and fanciful hat.[115] The capitals are placed in chronological order, beginning with God in the act of creation at the northwest corner, Adam and Eve in the west gallery, followed by the Binding of Isaac, and Matthew and John writing their gospels. Capitals in the south gallery illustrate scenes from the life of Christ.[116]

Gardens

[edit]The Cloisters' three gardens, the Judy Black Garden at the Cuxa Cloister on the main level, and the Bonnefont and Trie Cloisters gardens on the lower level,[117] were laid out and planted in 1938. They contain a variety of rare medieval species,[118] with a total of over 250 genera of plants, flowers, herbs and trees, making it one of the world's most important collections of specialized gardens. The garden's design was overseen by Rorimer during the museum's construction. He was aided by Margaret B. Freeman, who conducted extensive research into the keeping of plants and their symbolism in the Middle Ages.[119] Today the gardens are tended by a staff of horticulturalists; the senior members are also historians of 13th- and 14th-century gardening techniques.[120]

Interior

[edit]Gothic chapel

[edit]

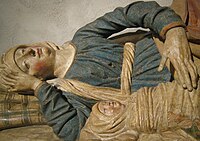

The Gothic chapel is set on the museum's ground level, and was built to display its stained glass and large sculpture collections. The entrance from the upper-level Early Gothic Hall is lit by stained glass double-lancet windows, carved on both sides and acquired from the church of La Tricherie, France.[121] The ground level is entered through a large door at its east wall. This entrance begins with a pointed Gothic arch leading to high bayed ceilings, ribbed vaults and buttress.[122] The three center windows are from the church of Sankt Leonhard, in southern Austria, from c. 1340. The glass panels include a depiction of Martin of Tours as well as complex medallion patterns.[122] The glass on the east wall comes from Évron Abbey, Maine, and dates from around 1325.[123] The apse contains three large sculptures by the main windows; two larger than life-size female saints dating from the 14th century, and a Burgundian Bishop dating from the 13th.[124] The large limestone sculpture of Saint Margaret on the wall by the stairs dates to around 1330 and is from the church of Santa Maria de Farfanya in Lleida, Catalonia.[122] Each of the six effigies are supreme examples of sepulchral art.[125] Three are from the Bellpuig Monastery in Catalonia.[125] The monument directly facing the main windows is the c. 1248–67 sarcophagus of Jean d'Alluye, a knight of the crusades, who was thought to have returned from the Holy Land with a relic of the True Cross. He is shown as a young man, his eyes open, and dressed in chain armor, with his longsword and shield.[124] The female effigy of a lady, found in Normandy, dates to the mid 13th century and is perhaps of Margaret of Gloucester.[126] Although resting on a modern base,[127] she is dressed in high contemporary aristocratic fashion, including a mantle, cotte, jewel-studded belt and an elaborate ring necklace brooch.[128]

Four of the effigies were made for the Urgell family, are set into the chapel walls, and are associated with the church of Santa Maria at Castello de Farfanya, Catalonia, redesigned in the Gothic style for Ermengol X (died c. 1314).[125] The elaborate sarcophagus of Ermengol VII, Count of Urgell (d. 1184) is placed on the left hand wall facing the chapel's south windows. It is supported by three stone lions, and a grouping of mourners carved into the slab, which also shows Christ in Majesty flanked by the Twelve Apostles.[129] The three other Urgell tombs also date to the mid 13th century, and maybe of Àlvar of Urgell and his second wife, Cecilia of Foix, the parents of Ermengol X, and that of a young boy, possibly Ermengol IX, the only one of their direct line ancestors known to have died in youth.[126] The slabs of the double tomb on the wall opposite Ermengol VII, contain the effigies of his parents, and have been slanted forward to offer a clear view of the stonework. The heads are placed on cushions, which are decorated with arms. The male's feet rest on a dog, while the cushion under the woman's head is held by an angel.[130]

Fuentidueña chapel

[edit]

The Fuentidueña chapel is the museum's largest room,[131] and is entered through a broad oak door flanked by sculptures that include leaping animals. Its centerpiece is the Fuentidueña Apse, a semicircular Romanesque recess built between about 1175 to 1200 at the Saint Joan church at Fuentidueña, Segovia.[132] By the 19th century, the church was long abandoned and in disrepair. The chapel was acquired by Rockefeller for the Cloisters in 1931, following three decades of complex negotiation and diplomacy between the Spanish church and both countries' art-historical hierarchies and governments. It was eventually exchanged in a deal that involved the transfer of six frescoes from San Baudelio de Berlanga to the Prado, on an equally long-term loan.[34] The structure was disassembled into almost 3,300 mostly sandstone and limestone blocks, each individually cataloged, and shipped to New York in 839 crates.[133] It was reconstructed at the Cloisters in the late 1940s[134] The build was large and complex enough that it required the demolition of the former "Special Exhibition Room". The chapel was opened to the public in 1961, seven years after its installation had begun.[135]

The apse consists of a broad arch leading to a barrel vault, and culminates with a half-dome.[136] The capitals at the entrance contain representations of the Adoration of the Magi and Daniel in the lions' den.[137] The piers show Martin of Tours on the left and the angel Gabriel announcing to The Virgin on the right. The chapel includes other, mostly contemporary, medieval artwork. They include, in the dome, a large fresco dating to between 1130 and 1150, from the Spanish Church of Sant Joan de Tredòs. The fresco's colourization resembles a Byzantine mosaic and is dedicated to the ideal of Mary as the mother of God.[138] Hanging within the apse is a crucifix made between about 1150 to 1200 for the Convent of St. Clara in Astudillo, Spain.[139] Its reverse contains a depiction of the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), decorated with red and blue foliage at its frames.[140] The exterior wall holds three small, narrow and stilted windows,[137] which are nevertheless designed to let in the maximum amount of light. The windows were originally set within imposing fortress walls; according to the art historian Bonnie Young "these small windows and the massive, fortress-like walls contribute to the feeling of austerity ... typical of Romanesque churches."[136]

Langon chapel

[edit]

The Langon chapel is on the museum's ground level. Its right wall was built around 1126 for the Romanesque Cathédrale Notre-Dame-du-Bourg de Digne.[141] The chapter house consists of a single aisle nave and transepts[142] taken from a small Benedictine parish church built around 1115 at Notre Dame de Pontaut.[143] When acquired, it was in disrepair, its upper level in use as a storage place for tobacco. About three-quarters of its original stonework was moved to New York.[142]

The chapel is entered from the Romanesque hall through a doorway, a large, elaborate French Gothic stone entrance commissioned by the Burgundian court[10] for Moutiers-Saint-Jean Abbey in Burgundy, France. Moutiers-Saint-Jean was sacked, burned, and rebuilt several times. In 1567, the Huguenot army removed the heads from the two kings, and in 1797 the abbey was sold as rubble for rebuilding. The site lay in ruin for decades and lost further sculptural elements until Barnard arranged for the entrances' transfer to New York. The doorway had been the main portal of the abbey, and was probably built as the south transept door.

Carvings on the elaborate white oolitic limestone doorway depict the Coronation of the Virgin and contains foliated capitals and statuettes on the outer piers; including two kings positioned in the embrasures and various kneeling angels. Carvings of angels are placed in the archivolts above the kings.[144] The large figurative sculptures on either side of the doorway represent the early Frankish kings Clovis I (d. 511) and his son Chlothar I (d. 561).[145][146] The piers are lined with elaborate and highly detailed rows of statuettes, which are mostly set in niches,[147] and are badly damaged; most have been decapitated. The heads on the right-hand capital were for a time believed to represent Henry II of England.[148] Seven capitals survive from the original church, with carvings of human figures or heads, some of which have been identified as historical persons, including Eleanor of Aquitaine.[142]

Romanesque hall

[edit]The Romanesque hall contains three large church doorways, with the main visitor entrance adjoining the Guilhem Cloister. The monumental arched Burgundian doorway is from Moutier-Saint-Jean de Réôme in France and dates to c. 1150.[10] Two animals are carved into the keystones; both rest on their hind legs as if about to attack each other. The capitals are lined with carvings of both real and imagined animals and birds, as well as leaves and other fauna.[149] The two earlier doorways are from Reugny, Allier, and Poitou in central France.[4] The hall contains four large early-13th-century stone sculptures representing the Adoration of the Magi, frescoes of a lion and a wyvern, each from the Monastery of San Pedro de Arlanza in north-central Spain.[10] On the left of the room are portraits of kings and angels, also from the monastery at Moutier-Saint-Jean.[149] The hall contains three pairs of columns positioned over an entrance with molded archivolts. They were taken from the Augustinian church at Reugny.[150] The Reugny site was badly damaged during the French Wars of Religion and again during the French Revolution. Most of the structures had been sold to a local man, Piere-Yon Verniere, by 1850, and were acquired by Barnard in 1906.[95]

Treasury room

[edit]The Treasury room was opened in 1988 to celebrate the museum's 50th anniversary. It largely consists of small luxury objects acquired by the Met after it had built its initial collection, and draws heavily on acquisitions from the collection of Joseph Brummer.[151] The rooms contain the museum's collection of illuminated manuscripts, the French 13th-century arm-shaped silver reliquary,[152] and a 15th-century deck of playing cards.[153]

Library and archives

[edit]The Cloisters contains one of the Metropolitan's 13 libraries. Focusing on medieval art and architecture, it holds over 15,000 volumes of books and journals, the museum's archive administration papers, curatorial papers, dealer records and the personal papers of Barnard, as well as early glass lantern slides of museum materials, manuscript facsimiles, scholarly records, maps and recordings of musical performances at the museum.[154] The library functions primarily as a resource for museum staff, but is available by appointment to researchers, art dealers, academics and students.[155] The archives contain early sketches and blueprints made during the early design phase of the museum's construction, as well as historical photographic collections. These include photographs of medieval objects from the collection of George Joseph Demotte, and a series taken during and just after World War II showing damage sustained to monuments and artifacts, including tomb effigies. They are, according to curator Lauren Jackson-Beck, of "prime importance to the art historian who is concerned with the identification of both the original work and later areas of reconstruction".[156] Two important series of prints are kept on microfilm: the "Index photographique de l'art en France" and the German "Marburg Picture Index".[156]

Governance

[edit]The Cloisters is governed by the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan's collections are owned by a private corporation of about 950 fellows and benefactors. The board of trustees comprise 41 elected members, several officials of the City of New York, and persons honored as trustees by the museum. The current chairman of the board is the businessman and art collector Daniel Brodsky, who was elected in 2011,[157] having previously served on its Real Estate Council in 1984 as a trustee of the museum and Vice Chairman of the Buildings Committee.[158]

Acquisition and deaccessioning

[edit]A specialist museum, the Cloisters regularly acquires new works and rarely sells or otherwise gets rid of them. While the Metropolitan does not publish separate figures for the Cloisters, the entity as a whole spent $39 million on acquisitions for the fiscal year ending in June 2012.[159] The Cloisters seeks to balance its collection between religious and secular artifacts and artworks. With secular pieces, it typically favors those that indicate the range of artistic production in the medieval period, and according to art historian Timothy Husband, "reflect the fabric of daily [medieval European] life but also endure as works of art in their own right".[160] In 2011 it purchased the then-recently discovered The Falcon's Bath, a Southern Netherlands tapestry dated c. 1400–1415. It is of exceptional quality, and one of the best preserved surviving examples of its type.[161] Other recent acquisitions of significance include the 2015 purchase of a Book of Hours attributed to Simon Bening.[48]

Exhibitions and programs

[edit]The museum's architectural settings, atmosphere, and acoustics have made it a regular setting both for musical recitals and as a stage for medieval theater. Notable stagings include The Miracle of Theophilus in 1942, and John Gassner's adaption of The Second Shepherds' Play in 1954.[162] Recent significant exhibitions include "Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures" which ran in the summer of 2017 in conjunction with the Art Gallery of Ontario and Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.[163]

Objects from the collection

[edit]-

Capital from the monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, French (Languedoc), after 804

-

Virgin and Child, French (Burgundy), 1130-1140

-

Reliquary Cross, metalwork, French, c. 1180

-

Lancet window, French (Normandy), c. 1250–1300

-

Enthroned Virgin and Child, ivory, English, c. 1290–1300

-

The Crucified Christ, ivory, from Paris, c. 1300

-

Leaf from the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, illuminated manuscript, French, c. 1324–28

-

Amatory Brooch, German, c. 1340–60

-

Appliqué Figure of Christ, French, 13th century

-

Alexander the Great or Hector of Troy, (detail), tapestry, France or South Lowlands, c. 1400–10

-

Apostle Spoon, silver, partial gilt, British, c. 1470

-

Adoration of the Magi, German, c. 1470–80

-

Nativity of the Virgin (detail), German, c. 1480

-

Statuette of Saint Barbara, limewood with paint, probably German, c. 1490

In popular culture

[edit]Since it opened in 1938, The Cloisters has been featured and referenced in many works of popular culture. One of the more prominent uses of the Cloisters as a setting took place in 1948, when director Maya Deren used its ramparts as a backdrop for her experimental film Meditation on Violence.[164] That year, German director William Dieterle used the Cloisters as the location for a convent school in his film Portrait of Jennie. The 1968 film Coogan's Bluff used the site's pathways and lanes for a scenic motorcycle chase.[164] In the 2021 Steven Spielberg film West Side Story, Maria (Rachel Zegler) and Tony (Ansel Elgort) go to the Cloisters on a date.[165]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Cloisters" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 19, 1974. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. 1978.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 1.

- ^ a b Landais 1992, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d "The Opening of the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 21, No. 5, 1926. pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e f Tomkins 1970, p. 308.

- ^ a b c d Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b Tomkins 1970, p. 309.

- ^ a b c Husband 2013, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Siple 1938, p. 88.

- ^ Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 38.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Tomkins 1970, p. 310.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Husband 2013, pp. 6 & 26.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 12.

- ^ "The Cloisters Museum and Gardens". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ^ Husband 2013, pp. 16–20.

- ^ Costa, Francesca (2022). "An "Oft-Repeated Anecdote"".

- ^ "Cloisters Opened on Tryon Heights". The New York Times. May 11, 1938. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- ^ "4,473 Visit the Cloisters". The New York Times. May 15, 1938. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- ^ Strouse 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b "The Making of a Collection: Islamic Art at the Metropolitan". Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2018

- ^ a b Brennan, Christine. "A Treasury for The Cloisters". Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 5, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2018

- ^ Freeman & Rorimer 1960, p. 2.

- ^ Ainsworth 2005, pp. 51–65.

- ^ "The Merode Altarpiece, a great and famous landmark in the history of western painting, by the Master of Flémalle, has been acquired for the Cloisters". Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 9, 1957. Retrieved March 30, 2018

- ^ "Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 17, 2017

- ^ "Workshop of Rogier van der Weyden: The Nativity". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 19, 2017

- ^ Young 1979, p. 140.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Kleinbauer 1980, p. 18.

- ^ a b Wixom 1988, p. 36.

- ^ Ellis & Suda 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Rorimer 1948, p. 260.

- ^ Rorimer 1948, p. 254.

- ^ Ellis & Suda 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Rorimer 1948, p. 237.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 125.

- ^ Ridderbos, Van Veen & Van Buren 2005, pp. 177 & 194.

- ^ Tomkins 1970, p. 313.

- ^ Cavallo 1998, p. 15.

- ^ Strouse 2000, p. 5.

- ^ a b Nickel, Hoffeld & Deuchler 1971, p. 1.

- ^ Deuchler 1969, p. 146.

- ^ Husband 2008, p. x.

- ^ a b "Annual Report for the Year 2014–15: Report from the Director and the President". Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 10, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2018

- ^ Nickel 1972, p. 64.

- ^ Deuchler 1971, p. 14-15.

- ^ Nickel, Hoffeld & Deuchler 1971, p. 10.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Ingo 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Pächt 1950, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Freeman 1956, pp. 93–101.

- ^ Deuchler 1971, p. 267.

- ^ a b Young 1979, p. 58.

- ^ Bolton 2018, p. 294.

- ^ a b Stoddard 1972, p. 425.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 62.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 65.

- ^ Siple 1938, p. 89.

- ^ Rorimer 1942, p. 13, 18.

- ^ Rorimer 1942, p. 39.

- ^ Rorimer 1942, p. 7.

- ^ Preston, Richard. "Capturing the Unicorn". The New Yorker, April 11, 2005. Retrieved February 26, 2018

- ^ Rorimer 1938, p. 19.

- ^ "Christ Is Born as Man's Redeemer (Episode from the Story of the Redemption of Man)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 24, 2018

- ^ "The Burgos Tapestry: A Study in Conservation". Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 22, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2018

- ^ "The Virgin Mary and Five Standing Saints above Predella Panels". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved October 27, 2017

- ^ Husband 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 36.

- ^ a b Husband 2013, p. 33.

- ^ Cotter, Holland. "Luminous Canterbury Pilgrims: Stained Glass at the Cloisters". The New York Times, February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2018

- ^ Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 31.

- ^ a b Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Hayward, Shepard & Clark 2012, p. 303.

- ^ a b Husband 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 35.

- ^ a b Husband 2013, p. 41.

- ^ a b Husband 2013, p. 38.

- ^ a b c "Cuxa Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ^ Young 1979, p. 47.

- ^ Dale 2001, p. 405.

- ^ a b Husband 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Bayard 1997, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Peck 1996, p. 31.

- ^ Dale 2001, p. 407.

- ^ Horste 1982, p. 126.

- ^ Calkins 2005, p. 112.

- ^ Dale 2001, p. 402.

- ^ Dale 2001, p. 406.

- ^ Dale 2001, p. 410.

- ^ a b c Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Forsyth 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Yarrow, Andrew. "A Date With Serenity At the Cloisters". The New York Times, June 13, 1986. Retrieved May 21, 2016

- ^ "Saint-Guilhem Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ^ Young 1979, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 26.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Bayard 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Rorimer & Serrell 1972, p. 20.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 93.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 98.

- ^ McGowan, Sarah. "The Bonnefont Cloister Herb Garden". Fordham University. Retrieved May 22, 2016

- ^ "Bonnefont Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ^ Young 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 12.

- ^ a b Rorimer & Serrell 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Young 1979, p. 96.

- ^ Young 1979, pp. 97–9.

- ^ "Gardens at The Met Cloisters". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 26, 2018

- ^ Bayard 1997, p. vii.

- ^ Bayard 1997, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Bayard 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Young 1979, p. 76.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 80.

- ^ a b Young 1979, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Young 1979, p. 82.

- ^ a b Young 1979, pp. 80–84.

- ^ "Tomb Effigy of a Lady". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved June 5, 2016

- ^ Reynolds Brown 1992, p. 409.

- ^ Rorimer & Serrell 1972, p. 88.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 86.

- ^ Rorimer 1951, p. 267.

- ^ "Crucifix". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 2, 2016

- ^ "Monumental Moving Job". New York: Life Magazine, October 20, 1961

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 38.

- ^ a b Young 1979, p. 14.

- ^ a b Wixom 1988, p. 38.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 17.

- ^ Husband 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Wixom 1988, p. 39.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Young 1979, p. 40.

- ^ Forsyth 1978, pp. 33, 38.

- ^ "Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 14, 2016

- ^ Rorimer & Serrell 1972, p. 28.

- ^ Forsyth 1978, p. 57.

- ^ "Chapel from Notre-Dame-du-Bourg at Langon. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 14, 2016,

- ^ a b Young 1979, p. 6.

- ^ Barnet & Wu 2005, p. 78.

- ^ "Medieval Treasury Reopens at The Cloisters". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 19, 2018

- ^ "Arm Reliquary". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 19, 2018

- ^ "The Cloisters Archived August 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". New York Magazine. Retrieved August 19, 2018

- ^ "The Cloisters Library and Archives". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ^ Jackson-Beck 1989, p. 1.

- ^ a b Jackson-Beck 1989, p. 2.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin. "A Hushed Departure at the Met Museum Reveals Entrenched Management Culture". The New York Times, April 02, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2018

- ^ "NYU Alumni: Daniel Brodsky". New York University. Retrieved March 30, 2018

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin. "Qatar Uses Its Riches to Buy Art Treasures". The New York Times, July 22, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2018

- ^ Husband 2016, p. 25.

- ^ "Annual Report for the Year 2010–11: Report from the Director and the President". Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 9, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2018

- ^ "Medieval Drama at The Cloisters". Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 5, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2018

- ^ "Annual Report for the Year 2016–17 Exhibitions and Installations". Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 14, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018

- ^ a b "The Cloisters in Popular Culture: 'Time in This Place Does Not Obey an Order'". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 23, 2018

- ^ Bouzereau, Laurent (2021). West Side Story the Making of the Steven Spielberg Film. Abrams. ISBN 9781419750632. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Ainsworth, Maryan W (2005). "Intentional alterations of early Netherlandish paintings". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 40: 51–66. doi:10.1086/met.40.20320643. S2CID 194131734.

- Barnet, Peter; Wu, Nancy Y. (2005). The Cloisters: Medieval Art and Architecture. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-176-6.

- Bayard, Tania (1997). Sweet Herbs and Sundry Flowers: Medieval Gardens and the Gardens of the Cloisters. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-775-4.

- Bolton, Andrew (2018). Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-58839-645-7.

- Calkins, Robert (2005). Monuments of Medieval Art. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80149-306-5.

- Cavallo, Adolph S. (1998). The Unicorn Tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-868-3.

- Dale, Thomas EA (2001). "Monsters, corporeal deformities, and phantasms in the cloister of St-Michel-de-Cuxa". The Art Bulletin. 83 (3): 402–436. doi:10.2307/3177236. JSTOR 3177236.

- Deuchler, Florens (February 1971). "Looking at Bonne of Luxembourg's Prayer Book". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 29 (6): 267–278. doi:10.2307/3258542. JSTOR 3258542.

- Deuchler, Florens (November 1969). "The Cloisters: A New Center for Mediaeval Studies". The Connoisseur: 145–436.

- Ellis, Lisa; Suda, Alexandra (2016). Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures. Ontario, Canada: Art Gallery of Ontario. ISBN 978-1-89424-390-2.

- Forsyth, Ilene H. (1992). "The monumental arts of the Romanesque period, recent research". In Elizabeth C. Parker; Mary B. Shepard (eds.). The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art/International Center of Medieval Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-635-1.

- Forsyth, William (1978). "A Gothic Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 13: 33–74. doi:10.2307/1512709. JSTOR 1512709. S2CID 193059932.

- Freeman, Margaret (December 1956). "A Book of Hours for the Duke of Berry". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 15 (1). New York, NY: 93–104. doi:10.2307/3257709. JSTOR 3257709.

- Freeman, Margaret; Rorimer, James (1960). The Nine Heroes Tapestries at the Cloisters. Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 937275929.

- Hayward, Jane; Shepard, Mary; Clark, Cynthia (October 2012). English and French Medieval Stained Glass in the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30019-318-3.

- Horste, Kathryn (1982). "Romanesque Sculpture in American Collections". Gesta. 21 (2): 33–39. doi:10.2307/766876. JSTOR 766876. S2CID 193467887.

- Husband, Timothy (Fall 2016). "Recent Acquisitions: A Selection, 2014–2016". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 74 (2): 1–100.

- Husband, Timothy (Spring 2013). "Creating the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 70 (4): 1, 4–48. JSTOR i24413106.

- Husband, Timothy (2008). The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-294-7.

- Husband, Timothy (2001). "Medieval Art and the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 59 (1): 37–55. doi:10.2307/3269168. JSTOR 3269168.

- Ingo, Walther (2014). Codices Illustres. Berlin: Taschen Verlag. ISBN 978-3-83655-379-7.

- Jackson-Beck, Lauren (1989). Bibliotheca Scholaria: Research Materials from the Cloisters Library. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Thomas J. Watson Library.

- Kleinbauer, Helmut (1980). "A Theory about the Early History of the Cloisters Apocalypse". Gesta. 19 (1).

- Landais, Hubert (1992). "The Cloisters or the Passion for the Middle Ages". In Elizabeth C. Parker; Mary B. Shepard (eds.). The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art/International Center of Medieval Art. ISBN 978-0-8709-9635-1.

- Nickel, Helmut (1972). "A Theory about the Early History of the Cloisters Apocalypse". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 6: 59–72. doi:10.2307/1512634. JSTOR 1512634. S2CID 193058491.

- Nickel, Helmut; Hoffeld, Jeffrey; Deuchler, Florens (1971). The Cloisters Apocalypse: An Early Fourteenth-Century Manuscript in Facsimile. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-110-3.

- Pächt, Otto (1950). "Early Italian Nature Studies and the Early Calendar Landscape". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 13 (1): 13–47. doi:10.2307/750141. JSTOR 750141. S2CID 244492096.

- Peck, Amelia, ed. (1996). Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-805-8.

- Reynolds Brown, Katharine (1992). "Six Gothic Brooches at The Cloisters". In Parker, Elizabeth; Mary B. Shepard (eds.). The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-635-1.

- Ridderbos, Bernhard; Van Veen, Henk Th.; Van Buren, Anne (2005). Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-614-5.

- Rorimer, James; Serrell, Katherine (1972). Medieval Monuments at the Cloisters as They Were and as They Are. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-027-4.

- Rorimer, James (1951). The Cloisters: The Building and the Collection of Mediaeval Art in Fort Tryon Park. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 222157219.

- Rorimer, James (May 1948). "A Treasury at the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 6 (9): 237–260. doi:10.2307/3258000. JSTOR i364086.

- Rorimer, James (Summer 1942). "The Unicorn Tapestries Were Made for Anne of Brittany". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 1 (1): 7–20. doi:10.2307/3257087. JSTOR 3257087.

- Rorimer, James (1938). "New Acquisitions for the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 33 (5): 3–19. doi:10.2307/3256261. JSTOR 3256261.

- Siple, Ella (August 1938). "Medieval Art at the New Cloisters and Elsewhere". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 73 (425): 83, 88–89. JSTOR 867467.

- Stoddard, Whitney (1972). Art and Architecture in Medieval France. New York, NY: Harper and Row. ISBN 978-0-06430-022-3.

- Strouse, Jean (Winter 2000). "J. Pierpont Morgan: Financier and Collector". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 57 (3): 1–67. doi:10.2307/3258853. JSTOR 3258853.

- Tomkins, Calvin (March 1970). "The Cloisters...The Cloisters...The Cloisters...". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 28 (7): 308–320. doi:10.2307/3258513. JSTOR 3258513.

- Wixom, William (Winter 1988). "Medieval Sculpture at The Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. 46 (3): 1–68.

- Young, Bonnie (1979). A Walk Through the Cloisters. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-203-2.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Curatorial department

- Cloisters digital collections

- Glories of Medieval Art: The Cloisters, documentary presented by Philippe de Montebello, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Timothy Husband at The Cloisters, Oxford University Press and Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Cloisters

- 1938 establishments in New York City

- Art museums and galleries established in 1938

- Art museums and galleries in Manhattan

- Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan

- European medieval architecture in the United States

- Institutions founded by the Rockefeller family

- Funerary art

- Medieval art

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Museums in Manhattan

- Relocated buildings and structures in New York City

- Washington Heights, Manhattan

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Sculpture gardens, trails and parks in New York (state)