Tipping points in the climate system: Difference between revisions

Impact not part of definition. Trying compromise Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

re-rm Yaklib's errors Tags: Manual revert Reverted |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

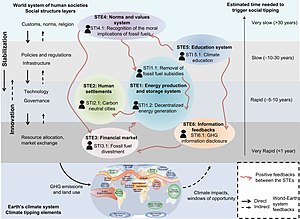

[[File:Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050 - Figure 3 - Social tipping elements and associated social tipping interventions with the potential to drive rapid decarbonization in the World–Earth system.jpg|thumb|300px|Interactions of climate tipping points (bottom) with associated tipping points in the socioeconomic system (top) on different time scales.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Otto|first1=I.M.|title=Social tipping elements for stabilizing climate by 2050 |journal=PNAS|date=February 4, 2020|volume=117|issue=5|pages=2354–2365|doi=10.1073/pnas.1900577117|pmid=31964839|pmc=7007533 }}</ref>]] |

[[File:Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050 - Figure 3 - Social tipping elements and associated social tipping interventions with the potential to drive rapid decarbonization in the World–Earth system.jpg|thumb|300px|Interactions of climate tipping points (bottom) with associated tipping points in the socioeconomic system (top) on different time scales.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Otto|first1=I.M.|title=Social tipping elements for stabilizing climate by 2050 |journal=PNAS|date=February 4, 2020|volume=117|issue=5|pages=2354–2365|doi=10.1073/pnas.1900577117|pmid=31964839|pmc=7007533 }}</ref>]] |

||

In climate science, a '''tipping point''' is a critical threshold that, when exceeded, leads to large and often irreversible changes in the state of the system. The term 'tipping point' is used by climate scientists to identify vulnerable features of the climate system.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2021-06-23|title=IPCC steps up warning on climate tipping points in leaked draft report|url=http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/23/climate-change-dangerous-thresholds-un-report|access-date=2021-07-22|website=The Guardian|language=en|archive-date=22 July 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210722124329/https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/23/climate-change-dangerous-thresholds-un-report|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last1=Lenton|first1=Timothy M.|last2=Rockström|first2=Johan|last3=Gaffney|first3=Owen|last4=Rahmstorf|first4=Stefan|last5=Richardson|first5=Katherine|last6=Steffen|first6=Will|last7=Schellnhuber|first7=Hans Joachim|date=2019-11-27|title=Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=575|issue=7784|pages=592–595|doi=10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0|pmid=31776487|doi-access=free|bibcode=2019Natur.575..592L}}</ref> |

|||

Large-scale components of the [[Earth system]] that may pass a tipping point are called tipping elements.<ref name="Lenton_2008">{{Cite journal |last1=Lenton |first1=T.M. |last2=Held |first2=H. |last3=Kriegler |first3=E. |last4=Hall |first4=J.W. |last5=Lucht |first5=W. |last6=Rahmstorf |first6=S. |last7=Schellnhuber |first7=H.J. |year=2008 |title=Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=105 |issue=6 |pages=1786–1793 |bibcode=2008PNAS..105.1786L |doi=10.1073/pnas.0705414105 |pmc=2538841 |pmid=18258748|doi-access=free }}</ref> At least 15 different elements of the climate system, such as the Greenland and [[Antarctic ice sheet]]s, have been identified as possible tipping points.<ref>[https://phys.org/news/2021-10-climate-scientists.html Climate scientists fear tipping points (maybe you should too)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211114035835/https://phys.org/news/2021-10-climate-scientists.html |date=14 November 2021 }}, PhysOrg, 25 October 2021.</ref><ref name="carbonbrief.org">[https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-nine-tipping-points-that-could-be-triggered-by-climate-change Explainer: Nine ‘tipping points’ that could be triggered by climate change] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200211090247/https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-nine-tipping-points-that-could-be-triggered-by-climate-change |date=11 February 2020 }}, Carbon Brief, 10 February 2020</ref> A danger is that if the tipping point in one system is crossed, this could lead to a cascade of other tipping points.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Wunderling|first1=Nico|last2=Donges|first2=Jonathan F.|last3=Kurths|first3=Jürgen|last4=Winkelmann|first4=Ricarda|date=2021-06-03|title=Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming|url=https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/12/601/2021/|journal=Earth System Dynamics|language=English|volume=12|issue=2|pages=601–619|doi=10.5194/esd-12-601-2021|bibcode=2021ESD....12..601W|s2cid=236247596|issn=2190-4979|access-date=4 June 2021|archive-date=4 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210604054226/https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/12/601/2021/|url-status=live}}</ref> If a cascade occurs, this could cause a [[Greenhouse and icehouse Earth#Greenhouse Earth|hothouse Earth]] in which global average temperatures would be higher than at any period in the past 1.2 million years.<ref name="Phys2018">{{cite news|last=Sheridan|first=Kerry|date=2018-08-06|title=Earth risks tipping into 'hothouse' state: study|work=Phys.org|url=https://phys.org/news/2018-08-earth-hothouse-state.html|access-date=2018-08-08|quote=Hothouse Earth is likely to be uncontrollable and dangerous to many ... global average temperatures would exceed those of any interglacial period—meaning warmer eras that come in between Ice Ages—of the past 1.2 million years.|archive-date=3 October 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191003151023/https://phys.org/news/2018-08-earth-hothouse-state.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

Large-scale components of the [[Earth system]] that may pass a tipping point are called tipping elements.<ref name="Lenton_2008">{{Cite journal |last1=Lenton |first1=T.M. |last2=Held |first2=H. |last3=Kriegler |first3=E. |last4=Hall |first4=J.W. |last5=Lucht |first5=W. |last6=Rahmstorf |first6=S. |last7=Schellnhuber |first7=H.J. |year=2008 |title=Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=105 |issue=6 |pages=1786–1793 |bibcode=2008PNAS..105.1786L |doi=10.1073/pnas.0705414105 |pmc=2538841 |pmid=18258748|doi-access=free }}</ref> At least 15 different elements of the climate system, such as the Greenland and [[Antarctic ice sheet]]s, have been identified as possible tipping points.<ref>[https://phys.org/news/2021-10-climate-scientists.html Climate scientists fear tipping points (maybe you should too)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211114035835/https://phys.org/news/2021-10-climate-scientists.html |date=14 November 2021 }}, PhysOrg, 25 October 2021.</ref><ref name="carbonbrief.org">[https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-nine-tipping-points-that-could-be-triggered-by-climate-change Explainer: Nine ‘tipping points’ that could be triggered by climate change] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200211090247/https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-nine-tipping-points-that-could-be-triggered-by-climate-change |date=11 February 2020 }}, Carbon Brief, 10 February 2020</ref> A danger is that if the tipping point in one system is crossed, this could lead to a cascade of other tipping points.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Wunderling|first1=Nico|last2=Donges|first2=Jonathan F.|last3=Kurths|first3=Jürgen|last4=Winkelmann|first4=Ricarda|date=2021-06-03|title=Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming|url=https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/12/601/2021/|journal=Earth System Dynamics|language=English|volume=12|issue=2|pages=601–619|doi=10.5194/esd-12-601-2021|bibcode=2021ESD....12..601W|s2cid=236247596|issn=2190-4979|access-date=4 June 2021|archive-date=4 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210604054226/https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/12/601/2021/|url-status=live}}</ref> If a cascade occurs, this could cause a [[Greenhouse and icehouse Earth#Greenhouse Earth|hothouse Earth]] in which global average temperatures would be higher than at any period in the past 1.2 million years.<ref name="Phys2018">{{cite news|last=Sheridan|first=Kerry|date=2018-08-06|title=Earth risks tipping into 'hothouse' state: study|work=Phys.org|url=https://phys.org/news/2018-08-earth-hothouse-state.html|access-date=2018-08-08|quote=Hothouse Earth is likely to be uncontrollable and dangerous to many ... global average temperatures would exceed those of any interglacial period—meaning warmer eras that come in between Ice Ages—of the past 1.2 million years.|archive-date=3 October 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191003151023/https://phys.org/news/2018-08-earth-hothouse-state.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:44, 24 November 2021

In climate science, a tipping point is a critical threshold that, when exceeded, leads to large and often irreversible changes in the state of the system. The term 'tipping point' is used by climate scientists to identify vulnerable features of the climate system.[2][3]

Large-scale components of the Earth system that may pass a tipping point are called tipping elements.[4] At least 15 different elements of the climate system, such as the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, have been identified as possible tipping points.[5][6] A danger is that if the tipping point in one system is crossed, this could lead to a cascade of other tipping points.[7] If a cascade occurs, this could cause a hothouse Earth in which global average temperatures would be higher than at any period in the past 1.2 million years.[8]

Tipping points are not necessarily abrupt. For example, even with a temperature rise between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, large parts of the Greenland ice sheet are likely to melt – but the melting process is set to take millennia.[9] A 2021 study of the Antarctic ice sheet has shown that tipping into full ice sheet retreat could take as little as ten years.[10][11]

Definition

Many positive and negative climate change feedbacks to global temperatures and the carbon cycle have been identified. For thousands of years, these feedback processes have mostly interacted to restore the system back to its previous steady state. If one component of the system starts to take significantly longer to return to its 'normal state', this may be a warning sign the system is approaching its tipping point.[12][13] What these different components in the system have in common is that once a tipping point is passed, and collapse has started, stopping it becomes virtually impossible.[6]

The Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2019 defines a tipping point as:

A level of change in system properties beyond which a system reorganises, often in a non-linear manner, and does not return to the initial state even if the drivers of the change are abated. For the climate system, the term refers to a critical threshold at which global or regional climate changes from one stable state to another stable state. Tipping points are also used when referring to impact: the term can imply that an impact tipping point is (about to be) reached in a natural or human system.[14]

The 2021 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report says that a tipping point in the climate system is a critical threshold beyond which a system reorganizes, often abruptly and/or irreversibly.[15]

Tipping points lead to changes in the climate system which are irreversible on a human timescale. For any particular climate component, the shift from one seemingly stable state to a less stable state may take many decades or centuries - although Palaeoclimate data and global climate models, suggest that the "climate system may abruptly 'tip' from one regime to another in a comparatively short time."[16]

Geological record

The geologic record of temperature and greenhouse gas concentration allows climate scientists to gather information on climate feedbacks that lead to different climate states. A key finding is that when the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere goes up, the average global temperature goes up with it.[17] In the last 100 million years, global temperatures have peaked twice, tipping the climate into a hothouse state. During the Cretaceous period, roughly 92 million years ago, CO2 levels were around 1,000 ppm.[8] The climate was so hot that crocodile-like reptiles lived in what is now the Canadian Arctic, and forests thrived near the South Pole. The second hothouse period was the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) 55-56 million years ago. Records suggest that during the PETM, the average global temperature rose between 5 and 8 °C; there was no ice at the poles, allowing palm trees and crocodiles to live above the Arctic Circle.[18]

However, as recently as three million years ago, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 matched today's levels. At that time, average global temperatures were 3C higher than they are now and sea levels were 5-to-25 metres higher.[19]

Combining this historical information with the understanding of current climate change resulted in the finding published in 2018 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that "a 2 °C warming could activate important tipping elements, raising the temperature further to activate other tipping elements in a domino-like cascade that could take the Earth System to even higher temperatures".[8][20]

Speed at which tipping occurs

The speed of tipping point feedbacks is a critical concern although the geologic record fails to provide clarity as to whether past temperature changes have taken only a few decades or many millennia. In March 2020, researchers showed that larger ecosystems can 'collapse' faster than previously thought, the Amazon rainforest for example (to a savanna) within ~50 years and the coral reefs of the Caribbean within ~15 years once a mode of 'collapse' is triggered, which in case of Amazonia they estimate could be as early as in 2021.[21][22][23][24]

In July 2021, Nature Geoscience published a review illustrating how cascading interactions in the Earth system have led to abrupt changes in climate, ecological and social systems during the past 30,000 years. The authors point out that "the geological record shows that abrupt changes can occur on timescales short enough to challenge the capacity of human societies to adapt to environmental pressures".[25]

Some scientists are concerned that some tipping points may have already been reached.[26] The greatest threat is from rising sea levels[27] and a 2018 study found that tipping points for the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets will likely occur between 1.5 and 2 °C of warming. The authors of the study point out that in 2021, the Earth has already warmed by 1.2 °C, and 1.5 °C of warming may be less than 15 years away. Based on current projections, experts say at least 20 feet (6.1 m) of sea-level rise is inevitable,[28] although the speed at which this will occur is uncertain.[29] Oceanographer, John Englander, says the last time sea-levels were rising quickly was 11,000 years ago, by about 15 feet (4.5 metres) per century.[30] A 2021 study of ocean floor sediments in the Antarctic's iceberg alley has shown that that tipping has occurred in the past on several occasions and that tipping can be sudden and full ice sheet retreat can take as little as ten years.[10]

Cascading tipping points

Crossing a threshold in one part of the climate system may trigger another tipping element to tip into a new state. These are called cascading tipping points.[31] Ice loss in West Antarctica and Greenland will significantly alter ocean circulation. Sustained warming of the northern high latitudes as a result of this process could activate tipping elements in that region, such as permafrost degradation, loss of Arctic sea ice, and boreal forest dieback.[3] Thawing permafrost poses a multiplier threat because it holds roughly twice as much carbon as the amount currently circulating in the atmosphere.[32] If this is released into the atmosphere, the world will have to cope with emissions generated by the planet itself as well as those generated by human use of fossil fuels.[33]

In 2019, Timothy Lenton and colleagues at Exeter University, published a study in Nature noting that the two most recent IPCC Special Reports, published in 2018 and 2019, suggest that even 1 and 2 °C of warming might push aspects of the climate past their tipping points.[34] The authors added that the risk of cascading tipping points is "much more likely and much more imminent" and that some "may already have been breached."[34]

In June 2021, Live Science reported that when scientists ran three million computer simulations of a climate model, nearly one-third of those simulations resulted in disastrous domino effects even when temperature increases were limited to 2 °C - the upper limit set by the Paris Agreement in 2015.[35] The authors of the Nature study acknowledge that the science of tipping points is complex such that there is great uncertainty as to how they might unfold, but nevertheless, argue that the possibility of cascading tipping points represents “an existential threat to civilisation”.[36]

Public concern

In April and May 2021, Ipsos Mori conducted an opinion survey in the G20 nations on behalf of the Global Commons Alliance (GCA). The results, published in August 2021, found 73% of those surveyed believe "Because of human activities, the Earth is close to ‘tipping points’ in nature where climate or nature may change suddenly, or may be more difficult to stabilise in the future".[37]: 34 People in poorer countries such as Indonesia, Turkey, and Brazil were significantly more aware of the risk of triggering tipping points than those in wealthier countries such as the United States, Japan, Great Britain and Australia.[37] This survey was conducted before the northern hemisphere summer of 2021 which saw record-breaking heatwaves, floods and fires, and before the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report warned of “inevitable and irreversible” climate change directly attributable to human activity.[38]

Mathematical theory

Tipping point behaviour in the climate can be described in mathematical terms. Tipping points are then seen as any type of bifurcation with hysteresis,[39][40] which is the dependence of the state of a system on its history. For instance, depending on how warm or cold it was in the past, there can be differing amounts of ice on the poles at the same concentration of greenhouse gases or temperature.[41] In a 2012 study inspired by "mathematical and statistical approaches to climate modelling and prediction", the authors identify three types of tipping points in open systems such as the climate system—bifurcation, noise-induced and rate-dependent.[16]

Types

Bifurcation-induced tipping

This occurs when a particular parameter in the climate, which is observed to be consistently moving in a given direction over a period of time, eventually passes through a critical level - at which point a dangerous bifurcation, or fork takes place - and what was a stable state loses its stability or simply disappears.[42] The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is like a conveyor belt driven by thermohaline circulation. Slow changes to the bifurcation parameters in this system — the salinity, temperature and density of the water - have caused circulation to slow down by about 15% in the last 70 years or so. If it reaches a critical point where it stops completely, this would be an example of bifurcation induced tipping.[43][44]

Noise-induced tipping

This refers to transitions from one state to another due to random fluctuations or internal variability of the system. Noise-induced transitions show none of the early warning signals which occur with bifurcations. This means they are fundamentally unpredictable as there is no systematic change in the underlying parameters. Because they are unpredictable, such occurrences are often described as a ‘one-in-x-year’ event.[45] An example is the Dansgaard–Oeschger events during the last glacial period, with 25 occurrences of sudden climate fluctuations over a 500 year period.[46]

Rate-induced tipping

This aspect of tipping assumes that there is a unique, stable state for any fixed aspect or parameter of the climate and that, if left undisturbed, there will only be small responses to a ‘small’ stimulus. However, when changes in one of the system parameters begin to occur more rapidly, a very large 'excitable' response may appear. In the case of peatlands, for instance, after years of relative stability, the rate-induced tipping point leads to an "explosive release of soil carbon from peatlands into the atmosphere" - sometimes known as "compost bomb instability".[47][48]

Mathematical early warning signals

For tipping points that occur because of a bifurcation, it may be possible to detect whether they are getting closer to a tipping point, as the system is getting less resilient to perturbations on approach of the tipping threshold. These systems display critical slowing down, with an increased memory (rising autocorrelation) and variance. Depending on the nature of the tipping system, changes may also be detected in the skewness and kurtosis of time series of relevant variables, with asymmetries in the distributions of anomalies indicating that tipping may be close.[49][12] Abrupt change is not an early warning signal (EWS) for tipping points, as abrupt change can also occur if the changes are reversible to the control parameter.[50][51]

These EWSs are often developed and tested using time series from the paleorecord, like sediments, ice caps, and tree rings, where past examples of tipping can be observed.[49][25] It is not always possible to say whether increased variance and autocorrelation is a precursor to tipping, or caused by internal variability, for instance in the case of the collapse of the AMOC.[25] Quality limitations of paleodata further complicate the development of EWSs.[25] They have been developed for detecting tipping due to drought in forests in California,[52] the Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica,[51] among other systems. Using early warning signals (increased autocorrelation and variance of the melt rate time series), it has been suggested that the Greenland ice sheet is currently losing resilience, consistent with modelled early warning signals of the ice sheet.[53]

However because the temperature is increasing so quickly there may be no warning.[54]: 1-66

Tipping elements

Scientists have identified a large set of system elements which are susceptible to become tipping points.[55][6] It is possible that some tipping points are close to being crossed or have already been crossed, like the ice sheets in West Antarctic and Greenland, warm-water coral reefs, and the Amazon rainforest.[56][57]

Shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

The AMOC is also known as the Gulf Stream System. Stefan Rahmstorf, professor of physics of the oceans at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research says: "The Gulf Stream System works like a giant conveyor belt, carrying warm surface water from the equator up north, and sending cold, low-salinity deep water back down south".[58] The process is driven by changes in salinity and temperature, described as thermohaline circulation. As warm water flows northwards, some evaporates which increases salinity. It also cools when it mixes with fresh water from melting ice in West Antarctica and Greenland. Cold, salty water is more dense and slowly begins to sink.[59] Several kilometres below the surface, cold, dense water then begins to move south. This cycle, which moves nearly 20 million cubic meters of water per second,[58] is the process of 'overturning'.

Rahmstorf says increased rainfall and the melting of continental ice due to global warming is diluting surface sea water and warming it up. "That makes the water lighter and, therefore, unable to sink – or less able to sink – which, basically, slows down that whole engine of the global overturning circulation".[60]

Theory, simplified models, and paleo observations of abrupt changes in the past, suggest the AMOC has a tipping point. These observations suggest that if freshwater input reaches a certain threshold (currently unknown), it could collapse into a state of reduced flow.[61]

Observed early warning signals

In 2018, studies found that the AMOC was at its weakest in at least 1,600 years, and was 15% weaker than in 400AD - described as "an exceptionally large deviation".[62] In August 2021, a study in Nature Climate Change said "significant early-warning signals" have been "found in eight independent AMOC indices"[63] suggesting that the AMOC "may be nearing a shutdown".[64]

Stefan Rahmstorf says the latest climate models suggest that if global warming continues at the current pace, by the end of this century, the system will have weakened by 34% to 45%. He says: "This could bring us dangerously close to the tipping point at which the flow becomes unstable".[65]

If the AMOC does shut down, a new stable state could emerge that lasts for thousands of years, possibly triggering other tipping points.[60]

West Antarctic ice sheet disintegration

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) is one of three regions making up Antarctica. In places it is more than 4 kilometres thick and sits on bedrock that largely lies below sea level.[66] As such, it is in contact with ocean heat, as well as warmer air which makes it vulnerable to rapid and irreversible ice loss. A tipping point could be reached if thinning or collapse of the WAIS's ice shelves triggers a feedback loop that leads to rapid and irreversible loss of land ice into the ocean - with the potential to raise sea levels by around 3.3 metres.[67]

The poles are warming more quickly than the rest of the planet and due to warming seas and warmer air, ice loss from the WAIS had tripled from 53 billion tonnes a year from 1992–97 to 159 billion tonnes a year between 2012–2017.[68] A study in Nature Geoscience says the palaeo record suggests that during the past few hundred thousand years, the WAIS largely disappeared in response to similar levels of warming and CO2 emission scenarios projected for the next few centuries.[69]

Amazon rainforest dieback

The Amazon rainforest is the largest tropical rainforest in the world. It is twice the size of India and spans nine countries in South America.[70] It generates around half of its own rainfall by recycling moisture through evaporation and transpiration as air moves across the forest.[71]

Deforestation of the Amazon began when colonists began establishing farms in the forest in the 1960s. They generally slashed and burned the trees in order to cultivate crops. However, soils in the Amazon are only productive for a short period after the land is cleared, so farmers would simply move and clear more land.[72] Other colonists cleared land to raise cattle, leading to further deforestation and environmental damage.[73] Heatwaves and drought have now become a factor driving additional tree deaths. This indicates that the Amazon is experiencing climatic conditions beyond its adaptative limits.[74] This process is described as dieback defined by the World Bank as “the process by which the Amazon basin loses biomass density as a consequence of changes in climate”.[75]

By 2019, at least 17% of the Amazon had already been lost.[76] That year, Jair Bolsonaro was elected President pledging to open up the rain forest for even more farming and mining and according to environmentalists his administration deliberately weakened environmental protection.[77] More than 70,000 forest fires broke out in the 12 months after he was elected, as farmers set fires to clear land for crops or cattle ranching.[78]

The result was that in 2020, deforestation rose another 17% caused by wildfires, beef production and logging.[79] In March 2021, the first long-term study of greenhouse gases in the Amazon rainforest found that in the 2010s the rainforest released more carbon dioxide than it absorbed.[80] The forest had previously been a carbon sink, but is now emitting a billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year. Deforestation has led to fewer trees which means more severe droughts and heatwaves develop leading to more tree deaths and more fires.[81][82]

West African monsoon shift

The West African Monsoon (WAM) system brings rainfall to West Africa and is the main source of rainfall in the agriculturally based region of the Sahel, an area of semi-arid grassland between the Sahara desert to the north and tropical rainforests to the south. The monsoon is a complex system in which land, ocean and atmosphere are connected is such a way that the wind direction reverses with the seasons.[83]

However, the monsoon is notoriously unreliable. Between the late 1960s and 1980s, the average rainfall declined by more than 30% plunging the region into an extended drought. This led to a famine that killed tens of thousands of people and triggered an international aid effort.[84] Research has shown the drought was largely due to changes in the surface temperatures of the global oceans, in particular, warming of the tropical oceans in response to rising greenhouse gases combined with cooling in the North Atlantic as a result of air pollution from northern hemisphere countries.[85]

Permafrost and methane hydrates

Permafrost is ground containing soil and/or organic material bound together by ice and which has remained frozen for at least two years.[86] It covers around a quarter of the non-glaciated land in the northern hemisphere – mainly in Siberia, Alaska, northern Canada and the Tibetan plateau – and can be as much as a kilometre thick.[87] Subsea permafrost up to 100 metres thick also occurs on the sea floor under part of the Arctic Ocean.[86] This frozen ground holds vast amounts of carbon, derived from plants and animals that have died and decomposed over thousands of years. Scientists believe there is nearly twice as much carbon in permafrost than is currently in the Earth's atmosphere.[88]

As the climate warms and the permafrost begins to thaw, carbon dioxide and methane are released into the atmosphere. Research conducted by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2019 found that thawing permafrost across the Arctic “could be releasing an estimated 300-600m tonnes of net carbon per year to the atmosphere”.[89] In a Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, the IPCC says there is “high confidence” in projections of “widespread disappearance of Arctic near-surface permafrost this century" which is "projected to release 10s to 100s of billions of tonnes [or gigatonnes, GtC], up to as much as 240 GtC, of permafrost carbon as CO2 and methane into the atmosphere".[90]

Warming in the Arctic allows the frozen permafrost to thaw, releasing locked up carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.[91] In June 2019, satellite images from around the Arctic showed burning fires that are farther north and of greater magnitude than at any time in the 16-year satellite record, and some of the fires appear to have ignited peat soils.[92] Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation and is an efficient carbon sink.[93] Scientists are concerned because the long-lasting peat fires release their stored carbon back to the atmosphere, contributing to further warming. The fires in June 2019, for example, released as much carbon dioxide as Sweden's annual greenhouse gas emissions.[94]

Coral reef die-off

Around 500 million people around the world depend on coral reefs for food, income, tourism and coastal protection.[95] Since the 1980s, this is being threatened by the increase in sea surface temperatures which is triggering mass bleaching of coral, especially in sub-tropical regions.[96] A sustained ocean temperature spike of 1 °C (1.8 °F) above average is enough to cause bleaching.[97] Under continued heat stress, corals expel the tiny colourful algae which live in their tissues leaving behind a white skeleton. The algae, known as zooxanthellae, have a symbiotic relationship with coral such that without them, the corals slowly die.[98]

Between 1979 - 2010, 35 coral reef bleaching events were identified at a variety of locations.[99] Some bleaching events are relatively localised, but the frequency and severity of mass-bleaching events affecting coral over hundreds and sometimes thousands of kilometres has been increasing over the last few decades.[100] Mass bleaching events occurred in 1998, 2010, and between 2014–2017. This three year event affected more than 70 percent of the world's coral reefs, leaving two thirds of the Great Barrier Reef dead or severely bleached. Scientific American reports that the world has lost around 50% of coral reefs in the past 30 years.[101] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that by the time temperatures have risen to 1.5C above pre-industrial times, between 70% and 90% of coral reefs that exist today will have disappeared; and that if the world warms by 2 °C, "coral reefs will be vanishingly rare".[102]

Indian monsoon shift

In India, the monsoon usually arrives in June, releasing 80% of the country's annual rainfall in four months.[103] The rains cools the atmosphere, water the crops, and fill rivers and wells - through to September. This has largely been the pattern for hundreds of years, although the timing has always varied to some extent and the intensity of the rain has often led to flooding.[104] Since 1950, the monsoon itself has weakened but, at the same time, there has been a 300% increase in extreme rainfall events over central India. Studies suggest these events are largely driven by a 1–2 °C increase in sea surface temperature in the north Arabian Sea, two to three weeks before the actual downpour - which generally lasts two or three days.[105] Most studies predict that as global warming continues, there will be more and more extreme rainfall events.[104]

Although India's summer monsoon has often precipitated floods, extreme rainfall events have exacerbated the problem. Between 1996 to 2005, there were 67 floods in India; in the following ten year period from 2006 to 2015, the number rose to 90. This affects the lives, food and water security of billions of people in the Indian subcontinent.[104] Most Indians rely on farming to make a living, and crops are highly sensitive to variabilities in rainfall. An analysis in 2017 found that up to $14.3 billion of India's GDP is exposed to river flooding, making India more vulnerable to extreme rain events than any other country in the world - and that this figure could rise 10-fold by 2030.[106] More conservatively, in 2018, the IPCC reported that if global temperatures rise by 3 degrees C, an increase in the intensity of monsoon rainfall is “likely”.[107]

Greenland ice sheet disintegration

The Greenland ice sheet is the second largest mass of ice in the world, and is three times the size of Texas.[108] It holds enough water, which if it melted, could raise global sea levels by 7.2 metres.[109] Due to global warming, the ice sheet is melting at an accelerating rate adding around 0.7 mm to global sea levels every year.[110] Around half of the ice loss occurs via surface melting, and the remainder occurs at the base of the ice sheet where the ice sheet touches the sea, by the breaking off, or 'calving', of icebergs from its edge.[111]

In June 2012, 97% of the entire ice sheet experienced surface melting for the first time in recorded history.[112] In 2019, Greenland lost a record 532 billion tons of ice, the most mass in any one year since at least 1948.[113] In 2020, researchers at Ohio State University said that snowfall in Greenland is no longer able to compensate for the loss of ice due to this melting, such that the disintegration of the ice sheet is now inevitable.[114]

In July 2021, in the space of less than a week, Greenland lost 18.4 billion tons of ice in the third extreme melting event in the last ten years, with loss of ice from a larger inland area of Greenland even than in 2019. Commenting on this event, Thomas Slater, a glaciologist at the University of Leeds said: "As the atmosphere continues to warm over Greenland, events such as yesterday's extreme melting will become more frequent".[115] Climate scientist, Dr Ruth Mottram of the Danish Meteorological Institute, says a tipping point for the melting of the Greenland ice sheet is unlikely to be abrupt but believes there will be a threshold beyond which its eventual collapse is irreversible.[116]

Boreal forest shift

Boreal forests, also known as taiga, are made up of trees that can cope with the cold such as conifers, spruce, fir, pine, larch, birch and aspen. They cover about 11% of the earth's land areas in northern latitudes across Alaska, Canada, northern Europe, and Russia.[117] They amount to 30% of the world's forests and constitute the largest ecosystem on land.[118] It is estimated that they hold more than one third of all terrestrial carbon.[119]

The boreal zone, along with the tundra to the north, is warming approximately twice as quickly as the global average.[120] A study in 2012 found that as the summers warm, it is becoming too hot for these particular tree species. This makes them vulnerable to disease, decreasing their reproduction rates.[121] A 2017 review in Nature Climate Change concluded that rapid warming and lower tree species diversity would lead to “disturbances” in boreal forests brought about by drought, fire, pests and disease.[122] In 2020, Woods Hole Research Center stated that global warming is increasing both the frequency and the severity of fires in boreal forests, and that these fires are releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.[123]

In regard to a potential tipping point, fires pose a significant risk. Prof Scott Goetz from Northern Arizona University, and science lead on NASA's Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment, says a tipping point in boreal forests could occur if an extreme fire event makes the forest incapable of regenerating and it becomes a sparsely wooded or grassland ecosystem.[124]

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation

Other examples of possible large scale tipping elements are a shift in El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Normally strong winds blow west across the South Pacific Ocean from South America to Australia. Every two to seven years, the winds weaken due to pressure changes and the air and water in the middle of the Pacific warms up, causing changes in wind movement patterns around the globe. This known as El Niño and it has led to droughts in Indonesia, India and Brazil, and increased flooding in Peru. In 2015/2016, this caused food shortages affecting over 60 million people.[125] El Niño-induced droughts may increase the likelihood of forest fires in the Amazon.[126]

So far, there is no definitive evidence indicating changes in ENSO behaviour.[127] However, the required global warming to push ENSO across the tipping point is likely to happen this century.[128] After crossing a tipping point, the warm El Niño phase would last longer and occur more often.

Arctic sea ice

The Arctic sea ice is warming twice as fast as the global average and in June 2020, the temperature was 18 °C higher than the average daily maximum for that month, the highest ever recorded in the Arctic circle.[129] As a result of long term warming, the oldest and thickest ice in the Arctic has declined by 95% during the last 30 years.[130] In August 2021, the IPCC said that under high CO2 emissions scenarios, the Arctic is likely to be ice-free in late summers by the end of the century (with high confidence). The IPCC also said that even if the ice disappears, this does not represent a tipping point because “projected losses are potentially reversible”.[131]

Clouds

Stratocumulus clouds shade roughly a fifth of the oceans. They reflect up to 60 percent of the solar radiation that hits them back into space, which helps to cool the Earth. A 2020 study predicts that a doubling of greenhouse gases would interfere with cloud formation. This could disperse stratocumulus clouds, enabling more solar energy to hit the planet, which could push global heating into overdrive.[132][133]

There is evidence this is already beginning to occur. NASA's Langley Research Center has found that since 2013, the rise in global average temperatures has coincided with a decline in cloud cover over the oceans. Other studies have found that during warmer years, fewer low-level clouds form in the tropics. [134]

Using a fine scale resolution model, Caltech climate scientist Tapio Schneider, believes global cloud cover has its own tipping point, beyond which clouds would become unstable and break up entirely. However, this would not be reached until CO2 levels were around 1200 ppm, three times current levels. If this occurred, he projected temperatures would soar by an additional 8 degrees C. Schneider suggests this “may have contributed to abrupt climate changes in the geological past.”[135]

Tipping point effects

If the climate tips into a state where tipping points begin to cascade, coastal storms will have greater impact, hundreds of millions of people will be displaced by rising sea levels, there will be food and water shortages, and people will die from unhealthy heat levels and generally unlivable conditions.[136] If cascading tipping points lead to climate temperature increases of 4–5 °C, this will make swathes of the planet around the equator uninhabitable, and lead to sea levels up to 60 metres (197 ft) higher than they are today.[137] Humans cannot survive if the air is too moist and hot, and billions of people may die. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research says if the world warms by this amount, it could only sustain about one billion people.[138]

A 2021 meta study, conducted by Simon Dietz, James Rising, Thomas Stoerk, and Gernot Wagner, on the potential economic impact of tipping points found that they raise global risk; the medium estimate was that they increase the social cost of carbon (SCC) by about 25%, with a 10% chance of tipping points more than doubling the SCC.[139] Effects like these have been popularized in books like The Uninhabitable Earth and The End of Nature.

Runaway greenhouse effect

The runaway greenhouse effect is used in astronomical circles to refer to a greenhouse effect that is so extreme that oceans boil away and render a planet uninhabitable, an irreversible climate state that happened on Venus. The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report states that "a 'runaway greenhouse effect' —analogous to Venus— appears to have virtually no chance of being induced by anthropogenic activities."[140] Venus-like conditions on the Earth require a large long-term forcing that is unlikely to occur until the sun brightens by a few tens of percents, which will take a few billion years.[141]

See also

- Greenhouse and icehouse Earth

- Climate sensitivity

- Planetary boundaries

- Climate engineering

- World Scientists' Warning to Humanity

References

- ^ Otto, I.M. (4 February 2020). "Social tipping elements for stabilizing climate by 2050". PNAS. 117 (5): 2354–2365. doi:10.1073/pnas.1900577117. PMC 7007533. PMID 31964839.

- ^ "IPCC steps up warning on climate tipping points in leaked draft report". The Guardian. 23 June 2021. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b Lenton, Timothy M.; Rockström, Johan; Gaffney, Owen; Rahmstorf, Stefan; Richardson, Katherine; Steffen, Will; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (27 November 2019). "Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against". Nature. 575 (7784): 592–595. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..592L. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. PMID 31776487.

- ^ Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. (2008). "Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (6): 1786–1793. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.1786L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705414105. PMC 2538841. PMID 18258748.

- ^ Climate scientists fear tipping points (maybe you should too) Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, PhysOrg, 25 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Explainer: Nine ‘tipping points’ that could be triggered by climate change Archived 11 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Carbon Brief, 10 February 2020

- ^ Wunderling, Nico; Donges, Jonathan F.; Kurths, Jürgen; Winkelmann, Ricarda (3 June 2021). "Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming". Earth System Dynamics. 12 (2): 601–619. Bibcode:2021ESD....12..601W. doi:10.5194/esd-12-601-2021. ISSN 2190-4979. S2CID 236247596. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Sheridan, Kerry (6 August 2018). "Earth risks tipping into 'hothouse' state: study". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

Hothouse Earth is likely to be uncontrollable and dangerous to many ... global average temperatures would exceed those of any interglacial period—meaning warmer eras that come in between Ice Ages—of the past 1.2 million years.

Cite error: The named reference "Phys2018" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Tipping points in Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets". NESSC. 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b Nield, David. "Warming Events Could Destabilize The Antarctic Ice Sheet Soon. Very Soon". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Weber, Michael E.; Golledge, Nicholas R.; Fogwill, Chris J.; Turney, Chris S. M.; Thomas, Zoë A. (18 November 2021). "Decadal-scale onset and termination of Antarctic ice-mass loss during the last deglaciation". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6683. Bibcode:2021EGUGA..23.3385W. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27053-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 34795275. S2CID 244402976. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b Lenton, Timothy .M.; Livina, V.N.; Dakos, V.; Van Nes, E.H.; Scheffer, M. (2012). "Early warning of climate tipping points from critical slowing down: comparing methods to improve robustness". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 370 (1962): 1185–1204. Bibcode:2012RSPTA.370.1185L. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0304. ISSN 1364-503X. PMC 3261433. PMID 22291229.

- ^ Williamson, Mark S.; Bathiany, Sebastian; Lenton, Tim (2016). "Early warning signals of tipping points in periodically forced systems". Earth System Dynamics. 7 (2): 313–326. Bibcode:2016ESD.....7..313W. doi:10.5194/esd-7-313-2016.

- ^ "Glossary — Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate". Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch4" (PDF). p. 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ a b Ashwin, Peter; Wieczorek, Sebastian; Vitolo, Renato; Cox, Peter (13 March 2012). "Tipping points in open systems: bifurcation, noise-induced and rate-dependent examples in the climate system". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 370 (1962): 1166–1184. arXiv:1103.0169. Bibcode:2012RSPTA.370.1166A. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0306. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 22291228. S2CID 2324694.

- ^ Temperature Change and Carbon Dioxide Change Archived 9 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, NOAA

- ^ What's the hottest Earth's ever been? Archived 19 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine NOAA, Climate.gov, June 18, 2020.

- ^ Climate scientists fear tipping points (maybe you should too) Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, PhysOrg, 25 October 2021

- ^ Wunderling, Nico; Donges, Jonathan F.; Kurths, Jürgen; Winkelmann, Ricarda (3 June 2021). "Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming". Earth System Dynamics. 12 (2): 601–619. Bibcode:2021ESD....12..601W. doi:10.5194/esd-12-601-2021. ISSN 2190-4979. S2CID 236247596. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Ecosystems the size of Amazon 'can collapse within decades'". The Guardian. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Amazon rainforest could be gone within a lifetime". EurekAlert!. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Ecosystems the size of Amazon 'can collapse within decades'". The Guardian. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Gregory S.; Willcock, Simon; Dearing, John A. (10 March 2020). "Regime shifts occur disproportionately faster in larger ecosystems". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 1175. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.1175C. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15029-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7064493. PMID 32157098.

- ^ a b c d Brovkin, Victor; Brook, Edward; Williams, John W.; Bathiany, Sebastian; et al. (29 July 2021). "Past abrupt changes, tipping points and cascading impacts in the Earth system". Nature Geoscience. 14 (8): 550–558. Bibcode:2021NatGe..14..550B. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00790-5. S2CID 236504982. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Climate tipping points may have been reached already, experts say Archived 29 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, 26 April 2021

- ^ Climate tipping points may have been reached already, experts say Archived 29 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, 26 April 2021

- ^ Climate tipping points may have been reached already, experts say Archived 29 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, 26 April 2021

- ^ sharing_token=fVO25MEHqfuwzWHhSlM79tRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0P_tXi6EBxQ8p_EcCElhVk0tdzJhz7WimQoXcx3FEoF_O9TbKckLMax8SHEm4OSNna5tDC2CZ5WlFugrI4bkHNvyYtmiV_PMhf3nz1LNZfaHWMpmVZxdpq5FrdDXjCy7OEsp9ZZ6q1O04pqCKibYY4_9wKXKmm0Wos7Ejxma-1h5iJniIRmo1TrBS3t_FfgRvs%3D&tracking_referrer=www.cbsnews.com The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets under 1.5 °C global warming Archived 15 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Climate Change, December 2018

- ^ Climate tipping points may have been reached already, experts say Archived 29 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CBS 26 April 2021.

- ^ Rocha, Juan C.; Peterson, Garry; Bodin, Örjan; Levin, Simon (2018). "Cascading regime shifts within and across scales". Science. 362 (6421): 1379–1383. Bibcode:2018Sci...362.1379R. doi:10.1126/science.aat7850. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30573623. S2CID 56582186.

- ^ The irreversible emissions of a permafrost ‘tipping point’ Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, World Economic Forum, 18 February 2020

- ^ Climate scientists fear tipping points (maybe you should too), PhysOrg, 25 October 2021

- ^ a b Lenton, Timothy M.; Rockström, Johan; Gaffney, Owen; Rahmstorf, Stefan; Richardson, Katherine; Steffen, Will; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (27 November 2019). "Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against". Nature. Comment. 575 (7784): 592–595. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..592L. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. PMID 31776487.

- ^ Climate 'tipping points' could push us past the point-of-no-return after less than 2 degrees of warming, Live Science, 13 June 2021

- ^ Climate emergency: world 'may have crossed tipping points’ Archived 4 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 27 November 2019

- ^ a b Gaffney, O., Tcholak-Antitch, Z., et al. Global Commons Survey: Attitudes to planetary stewardship and transformation among G20 countries Archived 16 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Global Commons Alliance (2021)

- ^ Humans ‘pushing Earth close to tipping point’, say most in G20 Archived 17 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 16 August 2021

- ^ Lenton, Timothy M.; Williams, Hywel T.P. (2013). "On the origin of planetary-scale tipping points". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 28 (7): 380–382. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2013.06.001. PMID 23777818.

- ^ Smith, Adam B.; Revilla, Eloy; Mindell, David P.; Matzke, Nicholas; Marshall, Charles; Kitzes, Justin; Gillespie, Rosemary; Williams, John W.; Vermeij, Geerat (2012). "Approaching a state shift in Earth's biosphere". Nature. 486 (7401): 52–58. Bibcode:2012Natur.486...52B. doi:10.1038/nature11018. hdl:10261/55208. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 22678279. S2CID 4788164.

- ^ Pollard, David; DeConto, Robert M. (2005). "Hysteresis in Cenozoic Antarctic ice-sheet variations". Global and Planetary Change. 45 (1–3): 9–12. Bibcode:2005GPC....45....9P. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.09.011.

- ^ Tipping Phenomena And Points Of No Return In Ecosystems: Beyond Classical Bifurcations Archived 11 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 22 November 2020.

- ^ Boulton, Chris A.; Allison, Lesley C.; Lenton, Timothy M. (December 2014). "Early warning signals of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation collapse in a fully coupled climate model". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 5752. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5752B. doi:10.1038/ncomms6752. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4268699. PMID 25482065.

- ^ Dijkstra, Henk A. "Characterization of the multiple equilibria regime in a global ocean model." Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 59.5 (2007): 695–705.

- ^ Early warning of climate tipping points Archived 9 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Climate Change, 19 June 2011, p.203

- ^ Ditlevsen, Peter D.; Johnsen, Sigfus J. (2010). "Tipping points: Early warning and wishful thinking". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (19): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3719703D. doi:10.1029/2010GL044486. ISSN 1944-8007.

- ^ Wieczorek, S.; Ashwin, P.; Luke, C. M.; Cox, P. M. (8 May 2011). "Excitability in ramped systems: the compost-bomb instability". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 467 (2129): 1243–1269. Bibcode:2011RSPSA.467.1243W. doi:10.1098/rspa.2010.0485. ISSN 1364-5021.

- ^ Luke, C. M.; Cox, P. M. (2011). "Soil carbon and climate change: from the Jenkinson effect to the compost-bomb instability". European Journal of Soil Science. 62 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01312.x. ISSN 1365-2389. S2CID 55462001. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b Thomas, Zoë A. (15 November 2016). "Using natural archives to detect climate and environmental tipping points in the Earth System". Quaternary Science Reviews. 152: 60–71. Bibcode:2016QSRv..152...60T. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.09.026. ISSN 0277-3791. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Rosier, Sebastian (6 April 2021). "Guest post: Identifying three 'tipping points' in Antarctica's Pine Island glacier". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b Rosier, Sebastian H. R.; Reese, Ronja; Donges, Jonathan F.; De Rydt, Jan; Gudmundsson, G. Hilmar; Winkelmann, Ricarda (25 March 2021). "The tipping points and early warning indicators for Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica". The Cryosphere. 15 (3): 1501–1516. Bibcode:2021TCry...15.1501R. doi:10.5194/tc-15-1501-2021. ISSN 1994-0416. S2CID 233738686. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Liu, Yanlan; Kumar, Mukesh; Katul, Gabriel G.; Porporato, Amilcare (November 2019). "Reduced resilience as an early warning signal of forest mortality". Nature Climate Change. 9 (11): 880–885. Bibcode:2019NatCC...9..880L. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0583-9. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 203848411. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Boers, Niklas; Rypdal, Martin (25 May 2021). "Critical slowing down suggests that the western Greenland Ice Sheet is close to a tipping point". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (21): e2024192118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11824192B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2024192118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8166178. PMID 34001613.

- ^ "AR6 WG1 full report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Defined in IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter_04 Archived 5 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, p.95, line 34.

- ^ Critical measures of global heating reaching tipping point, study finds Archived 22 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 28 July 2021

- ^ Ripple, William J; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Gregg, Jillian W; Lenton, Timothy M; Palomo, Ignacio; Eikelboom, Jasper A J; Law, Beverly E; Huq, Saleemul; Duffy, Philip B; Rockström, Johan (28 July 2021). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2021". BioScience. 71 (biab079): 894–898. doi:10.1093/biosci/biab079. hdl:1808/30278. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ^ a b Gulf Stream System at its weakest in over a millennium Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Science Daily, February 25, 2021

- ^ Why does the ocean get colder at depth? Archived 13 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine National ocean Service

- ^ a b Explainer: Nine ‘tipping points’ that could be triggered by climate change Archived 11 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Carbon Brief, 10 Feb 2020

- ^ What is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation? Archived 15 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine UK Met Office

- ^ Gulf Stream current at its weakest in 1,600 years, studies show Archived 3 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 11 April 2018

- ^ Boers, N. Observation-based early-warning signals for a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Archived 7 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 680–688 (2021).

- ^ Climate crisis: Scientists spot warning signs of Gulf Stream collapse Archived 7 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 5 August 2021

- ^ Gulf Stream System at its weakest in over a millennium Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Science Daily, 25 Feb 2021

- ^ Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica Archived 21 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Cryosphere, 7, 375–393, 2013

- ^ Reassessment of the Potential Sea-Level Rise from a Collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Archived 19 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Science 15 May 2009: Vol. 324, Issue 5929, pp. 901-903

- ^ Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017 Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature, volume 558, pages219–222 (2018)

- ^ Stability of the West Antarctic ice sheet in a warming world Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Geoscience (2011) Volume 4, pp 506–513

- ^ Inside the Amazon Archived 9 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, WWF

- ^ Recycling of water in the Amazon Basin: An isotopic study Archived 18 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Water Resources Research

- ^ Watkins and Griffiths, J. (2000). Forest Destruction and Sustainable Agriculture in the Brazilian Amazon: a Literature Review (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Reading, 2000). Dissertation Abstracts International, 15-17

- ^ Williams, M. (2006). Deforesting the Earth: From Prehistory to Global Crisis. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Huge study reveals why trees in the Amazon die Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, European Scientist, 11 November 2020

- ^ Amazon Dieback and the 21st Century Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BioScience, Volume 61, Issue 3, March 2011, Pages 176–182

- ^ We aren't terrified enough about losing the Amazon Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Technology review, August 26, 2019.

- ^ "They are killing our forest, Brazilian tribe warns". BBC News. 28 April 2021. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ The Brazilian Amazon is on fire—here's why that's bad news for the planet Archived 20 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Technology review 21 August 2019

- ^ Amazon deforestation rose 17% in 'dire' 2020, data shows Archived 13 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, April 8, 2021

- ^ First study of all Amazon greenhouse gases suggests the damaged forest is now worsening climate change Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, National Geographic, 12 March 2021

- ^ Amazon rainforest now emitting more CO2 than it absorbs Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 14 July 2021

- ^ Preventing An Amazon Forest Dieback Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Earth Innovation Institute, March 2020

- ^ Transport pathways across the West African Monsoon as revealed by Lagrangian Coherent Structures Archived 16 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Scientific Reports volume 10, Article number: 12543 (2020)

- ^ Sahel Drought: Understanding the Past and Projecting into the Future Archived 18 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

- ^ The role of aerosols and greenhouse gases in Sahel drought and recovery Archived 31 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Climatic Change volume 152, pages449–466 (2019)

- ^ a b All About Frozen Ground Archived 17 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, National Snow and Ice Data centre

- ^ Statistics and characteristics of permafrost and ground-ice distribution in the Northern Hemisphere Archived 20 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Polar Geography, Volume 31, 2008

- ^ All About Frozen Ground Archived 20 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, National Snow and Ice Data Centre

- ^ A Arctic Report Card: Update for 2019 Archived 19 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, NOAA Arctic programme

- ^ S Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate Archived 12 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, IPCC

- ^ Arctic Circle sees 'highest-ever' recorded temperatures Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 22 June 2020

- ^ Hines, Morgan (23 January 2019). "Thanks to climate change, parts of the Arctic are on fire. Scientists are concerned". USA Today. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Hugron, Sandrine; Bussières, Julie; Rochefort, Line (2013). Tree plantations within the context of ecological restoration of peatlands: practical guide (PDF) (Report). Laval, Québec, Canada: Peatland Ecology Research Group (PERG). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Edward Helmore (26 July 2019). "'Unprecedented': more than 100 Arctic wildfires burn in worst ever season". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Scientists are trying to save coral reefs. Here's what's working. Archived 24 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine National Geographic, 5 June 2020

- ^ Hughes, TP, Kerry, JT, Álvarez-Noriega, M et al. (43 more authors) (2017) Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals Archived 22 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Nature, 543 (7645). pp. 373-377.

- ^ A most beautiful death Archived 24 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Time

- ^ ‘Bright white skeletons’: some Western Australian reefs have the lowest coral cover on record Archived 22 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation

- ^ Impact of Global Warming on Coral Reefs Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, WJST 2011

- ^ Mass Bleaching Archived 24 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Reef Resilience Network

- ^ Scientists Are Taking Extreme Steps to Help Corals Survive Archived 24 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Scientific American, 1 January 2018

- ^ The Great Barrier Reef is a victim of climate change – but it could be part of the solution Archived 27 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 26 July 2021

- ^ Climate change makes Indian monsoon season stronger and more chaotic Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, DW

- ^ a b c As the Monsoon and Climate Shift, India Faces Worsening Floods Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Environment 360, 17 September 2019

- ^ A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Communications, 3 October 2017

- ^ World's 15 Countries with the Most People Exposed to River Floods Archived 25 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, World Resources Institute, 5 March 2015

- ^ SPECIAL REPORT: GLOBAL WARMING OF 1.5 ºC, Impacts of 1.5ºC global warming on natural and human systems Archived 26 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, IPCC, 2018

- ^ Quick Facts on Ice Sheets Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, National Snow and Ice Data centre

- ^ New climate models suggest faster melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, World Economic Forum, 21 December 2020

- ^ Acceleration of the contribution of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to sea level rise Archived 22 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 38, L05503, doi:10.1029/2011GL046583, 2011

- ^ A Full-Stokes 3-D Calving Model Applied to a Large Greenlandic Glacier Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, AGU, 30 January 2018

- ^ An intense Greenland melt season: 2012 in review Archived 5 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Greenland Ice Sheet Today, 5 February 2013

- ^ Study: 2019 Sees Record Loss of Greenland Ice Archived 30 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Global Climate Change, 20 August 2020

- ^ Greenland ice melting past 'tipping point': Study. Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine New Straits Times, 18 August 2020

- ^ The amount of Greenland ice that melted on Tuesday could cover Florida in 2 inches of water Archived 30 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 29 July, 2021

- ^ Ruth Mottram - The melting of Greenland's ice sheet Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, RNZ, 31 August 2019.

- ^ Boreal Forest Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Science Direct, N.A. Balliet, C.D.B. Hawkins, in Encyclopedia of Forest Sciences, 2004

- ^ The Rapid and Startling Decline Of World's Vast Boreal Forests Archived 1 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Environment 360, 12 October 2015

- ^ Young and old forest in the boreal: critical stages of ecosystem dynamics and management under global change Archived 21 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Forest Ecosystems volume 5, Article number: 26 (2018)

- ^ Thresholds for boreal biome transitions Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, PNAS December 26, 2012 109 (52) 21384-21389

- ^ Arctic Climate Tipping Points Archived 12 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, AMBIO volume 41, pages10–22 (2012)

- ^ Forest disturbances under climate change Archived 14 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Climate Change volume 7, pages 395–402 (2017)

- ^ Southern Canadian boreal forest emissions grow as fires worsen Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Woodwell Climate Research Centre, 15 July 2020

- ^ Nine ‘tipping points’ that could be triggered by climate change Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Global Earth Observation and Dynamics of Ecosystems Lab (GEODE), NAU 11 February 2020

- ^ Tipping Points: Why we might not be able to reverse climate change Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Climate Science, 3 June 2021

- ^ Tipping the ENSO into a permanent El Niño can trigger state transitions in global terrestrial ecosystems Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Earth System Dynamics, 10, 631–650, 2019

- ^ Tipping the ENSO into a permanent El Niño can trigger state transitions in global terrestrial ecosystems Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Earth System Dynamics, 10, 631–650, 2019

- ^ Tipping Points: Why we might not be able to reverse climate change Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Climate Science, 3 June 2021

- ^ Arctic Circle sees 'highest-ever' recorded temperatures Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 22 June 2020

- ^ Six ways loss of Arctic ice impacts everyone Archived 28 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, WWF

- ^ IPCC_AR6_WGI_TS.pdf Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, p.43

- ^ Why Clouds Are the Key to New Troubling Projections on Warming Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Environment, 5 February 2020

- ^ IPCC AR5 (2013). "Technical Summary- TFE.6 Climate Sensitivity and Feedbacks" (PDF). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

The water vapour/lapse rate, albedo and cloud feedbacks are the principal determinants of equilibrium climate sensitivity. All of these feedbacks are assessed to be positive, but with different levels of likelihood assigned ranging from likely to extremely likely. Therefore, there is high confidence that the net feedback is positive and the black body response of the climate to a forcing will therefore be amplified. Cloud feedbacks continue to be the largest uncertainty.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Why Clouds Are the Key to New Troubling Projections on Warming Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Environment, 5 February 2020

- ^ Why Clouds Are the Key to New Troubling Projections on Warming Archived 14 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Environment, 5 February 2020

- ^ Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Scheffer, Marten; Lade, Steven J.; Fetzer, Ingo; Donges, Jonathan F.; Crucifix, Michel; Cornell, Sarah E.; Barnosky, Anthony D. (2018). "Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (33): 8252–8259. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.8252S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810141115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6099852. PMID 30082409.

- ^ "Earth 'just decades away from global warming tipping point which threatens future of humanity'". ITV News. 6 August 2018. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Earth risks tipping into 'hothouse' state: study Archived 3 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, PhysOrg, 6 August 2018

- ^ Simon Dietz; James Rising; Thomas Stoerk; Gernot Wagner (24 August 2021). "Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (34): e2103081118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11803081D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2103081118. PMC 8403967. PMID 34400500.

- ^ Scoping of the IPCC 5th Assessment Report Cross Cutting Issues (PDF). Thirty-first Session of the IPCC Bali, 26–29 October 2009 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Hansen, James; Sato, Makiko; Russell, Gary; Kharecha, Pushker (2013). "Climate sensitivity, sea level and atmospheric carbon dioxide". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 371 (2001). 20120294. arXiv:1211.4846. Bibcode:2013RSPTA.37120294H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2012.0294. PMC 3785813. PMID 24043864.