Breast: Difference between revisions

m _Maximum_ of two drinks |

added {{Seven dirty words}} template |

||

| Line 202: | Line 202: | ||

{{Breast anatomy}} |

{{Breast anatomy}} |

||

{{sex}} |

{{sex}} |

||

{{Seven dirty words}} |

|||

[[Category:Breast|*]] |

[[Category:Breast|*]] |

||

Revision as of 06:22, 4 November 2009

| Breast | |

|---|---|

The breast of a pregnant woman | |

| Details | |

| Artery | internal thoracic artery |

| Vein | internal thoracic vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | mamma (cf. mammal from Latin mammalis "of the breast"[1]) |

| MeSH | D001940 |

| TA98 | A16.0.02.001 |

| TA2 | 7097 |

| FMA | 9601 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The breast is the upper ventral region of an animal’s torso, particularly that of mammals, including human beings. The breasts of a female primate’s body contain the mammary glands, which secrete milk used to feed infants.

Both men and women develop breasts from the same embryological tissues. However, at puberty female sex hormones, mainly estrogens, promote breast development, which does not happen with men. As a result women's breasts become far more prominent than men's.

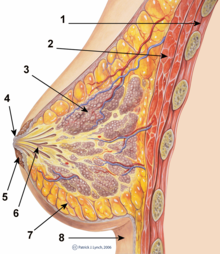

Anatomy

Breasts are modified sudoriferous (sweat) glands which produce milk in women, and in some rare cases, in men.[2] Each breast has one nipple surrounded by the areola. The areola is colored from pink to dark brown and has several sebaceous glands. In women, the larger mammary glands within the breast produce the milk. They are distributed throughout the breast, with two-thirds of the tissue found within 30 mm of the base of the nipple.[3] These are drained to the nipple by between 4 and 18 lactiferous ducts, where each duct has its own opening. The network formed by these ducts is complex, like the tangled roots of a tree. It is not always arranged radially, and branches close to the nipple. The ducts near the nipple do not act as milk reservoirs; Ramsay et al. have shown that conventionally described lactiferous sinuses do not, in fact, exist. Instead, most milk is actually in the back of the breast, and when suckling occurs, the smooth muscles of the gland push more milk forward.

The remainder of the breast is composed of connective tissue (collagen and elastin), adipose tissue (fat), and Cooper's ligaments. The ratio of glands to adipose tissues rises from 1:1 in nonlactating women to 2:1 in lactating women.[3]

The breasts sit over the pectoralis major muscle and usually extend from the level of the 2nd rib to the level of the 6th rib anteriorly. The superior lateral quadrant of the breast extends diagonally upwards towards the axillae and is known as the tail of Spence. A thin layer of mammary tissue extends from the clavicle above to the seventh or eighth ribs below and from the midline to the edge of the latissimus dorsi posteriorly. (For further explanation, see anatomical terms of location.)

The arterial blood supply to the breasts is derived from the internal thoracic artery (formerly called the internal mammary artery), lateral thoracic artery, thoracoacromial artery, and posterior intercostal arteries. The venous drainage of the breast is mainly to the axillary vein, but there is some drainage to the internal thoracic vein and the intercostal veins. Both sexes have a large concentration of blood vessels and nerves in their nipples. The nipples of both women and men can become erect in response to sexual stimuli,[4] and to cold.

The breast is innervated by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the fourth through sixth intercostal nerves. The nipple is supplied by the T4 dermatome.

Lymphatic drainage

About 75% of lymph from the breast travels to the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes. The rest travels to parasternal nodes, to the other breast, or abdominal lymph nodes. The axillary nodes include the pectoral, subscapular, and humeral groups of lymph nodes. These drain to the central axillary lymph nodes, then to the apical axillary lymph nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the breasts is particularly relevant to oncology, since breast cancer is a common cancer and cancer cells can break away from a tumour and spread to other parts of the body through the lymph system by metastasis.

Shape and support

Breasts vary in size, shape and position on a woman's chest, and their external appearance is not predictive of their internal anatomy or lactation potential. The natural shape of a woman's breasts is primarily dependent on the support provided by the Cooper's ligaments and the underlying chest on which they rest (the base). The breast is attached at its base to the chest wall by the deep fascia over the pectoral muscles. On its upper surface it is given some support by the covering skin where it continues on to the upper chest wall. It is this support which determines the shape of the breasts. In a small number of women, the frontal ducts (ampullae) in the breasts are not flush with the surrounding breast tissue, which causes the sinus area to visibly bulge outward.

Some breasts are high and rounded, and protrude almost horizontally from the chest wall. Such high breasts are common for girls and women in early stages of development. The protruding or high breasts are anchored to the chest at the base, and the weight is distributed evenly over the area of the base of the approximately dome- or cone-shaped breasts.

In the “low” breast, a proportion of the breasts' weight is actually supported by the chest against which the lower breast surface comes to rest, as well as the deep anchorage at the base. The weight is thus distributed over a larger area, which has the effect of reducing the strain. In both males and females, the thoracic cavity slopes progressively outwards from the thoracic inlet (at the top of the breastbone) above to the lowest ribs which mark its lower boundary, allowing it to support the breasts.

The inframammary fold (or line, or crease) is an anatomic structure created by adherence between elements in the skin and underlying connective tissue[5] and represents the inferior extent of breast anatomy. Some teenagers may develop breasts whose skin comes into contact with the chest below the fold at an early age, and some women may never develop such breasts; both situations are perfectly normal. The relationship of the nipple position to the fold is described as ptosis, a term also applied to other body parts and which refers in general to drooping or sagging. Due to breast weight and relaxation of support structures, the nipple-areola complex and breast tissue may eventually hang below the fold, and in some cases the breasts may extend as far as, or even beyond, the navel. The length from the nipple to the sternal notch (central, upper border) in the youthful breast averages 21 cm and is a common anthropometric figure used to assess both breast symmetry and ptosis. Lengthening of both this measurement and the distance between the nipple and the fold are both characteristic of advancing grades of ptosis.

The end of the breast, which includes the nipple, may either be flat (a 180° angle) or angled (angles lower than 180°). Breast ends are rarely angled sharper than 60°. Angling of the end of the breast is caused in part by the ligaments that suspend it, such that the breast ends often have a more obtuse angle when a woman is lying on her back. Breasts exist in a range of ratios between length and base diameter, usually ranging from ½ to 1.

Development

Girls develop breasts during puberty, as a result of changing sex hormones, chiefly estrogen, which also has been demonstrated to cause the development of woman-like, enlarged breasts in men, a condition called gynecomastia.

In most cases, the breasts fold down over the chest wall during Tanner stage development, as shown in this diagram.[6] It is typical for a woman's breasts to be unequal in size particularly while the breasts are developing. Statistically it is slightly more common for the left breast to be the larger.[7] In rare cases, the breasts may be significantly different in size, or one breast may fail to develop entirely.

A large number of medical conditions are known to cause abnormal development of the breasts during puberty. Virginal breast hypertrophy is a condition which involves excessive growth of the breasts, and in some cases the continued growth beyond the usual pubescent age. Breast hypoplasia is a condition where one or both breasts fail to develop.

Changes

As breasts are mostly composed of adipose tissue, their size can change over time. This occurs for a number of reasons, most obviously when a girl grows during puberty and when a woman becomes pregnant. The breast size may also change if she gains (or loses) weight for any other reason. Any rapid increase in size of the breasts can result in the appearance of stretchmarks.

It is typical for a number of other changes to occur during pregnancy: in addition to becoming larger, the breasts generally become firmer, mainly due to hypertrophy of the mammary gland in response to the hormone prolactin. The size of the nipples may increase noticeably and their pigmentation may become darker. These changes may continue during breastfeeding. The breasts generally revert to approximately their previous size after pregnancy, although there may be some increased sagging and stretchmarks.

The size of a woman's breasts may fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, particularly with premenstrual water retention. An increase in breast size is a common side effect of use of the combined oral contraceptive pill.

Breasts sag if the ligaments become elongated, a natural process that can occur over time and is also influenced by the breast bouncing while exercising. Breasts can decrease in size at menopause if estrogen levels decline.

Function

Breastfeeding

The primary function of mammary glands is to nurture young by producing breast milk. The production of milk is called lactation. (While the mammary glands that produce milk are present in the male, they normally remain undeveloped.) The orb-like shape of breasts may help limit heat loss, as a fairly high temperature is required for the production of milk. Alternatively, one theory states that the shape of the human breast evolved in order to prevent infants from suffocating while feeding.[8] Since human infants have a small jaw (not protruding, like other primates), the infant's nose might be blocked if the mother's chest was too flat.[8] According to this theory, as the human jaw receded, the breasts became larger to compensate.[8]

Milk production unrelated to pregnancy can also occur. This condition, called galactorrhea, may be an adverse effect of some medicinal drugs (such as some antipsychotic medication), extreme physical stress or endocrine disorders. If it occurs in men it is called male lactation, and is often classified as a pathological symptom due to its strong correlation to pituitary disorders. Newborn babies are often capable of lactation because they receive the hormones prolactin and oxytocin via the mother's bloodstream, filtered through the placenta. This neonatal liquid is known colloquially as witch's milk.

Sexual role

Breasts play an important part in human sexual behavior; they are also important female secondary sex characteristics.[9] Compared to other primates, human breasts are proportionately large throughout adult females' lives and may have evolved as a visual signal of sexual maturity and fertility.[10] On sexual arousal breast size increases, venous patterns across the breasts become more visible, and nipples harden. Breasts are sensitive to touch as they have many nerve endings, and it is common to press or massage breasts with hands during sexual intercourse (as it is with other bodily areas representing feminine secondary sex characteristics as well). Oral stimulation of nipples and breasts is also common. Some women can achieve breast orgasms.

Some people regard exposed breasts to be aestheticly pleasing and/or erotic. In the ancient Indian work the Kama Sutra, marking breasts with nails and biting with teeth are explained as erotic.[11]

- See also: Mammary intercourse; Toplessness; Breast fetishism; Cleavage.

Other suggested functions

Zoologists point out that no female mammal other than the human has breasts of comparable size, relative to the rest of the body, when not lactating and that humans are the only primate that has permanently swollen breasts. This suggests that the external form of the breasts is connected to factors other than lactation alone.[citation needed]

Some zoologists (notably Desmond Morris) believe that the shape of female breasts evolved as a frontal counterpart to that of the buttocks, the reason being that while other primates mate in the rear-entry position, humans, because of their upright posture, are more likely to successfully copulate by mating face to face, the so-called missionary position. Morris suggested in 1967 that a secondary sexual characteristic on a woman's chest would have encouraged this in more primitive incarnations of the human race, and a face on encounter may have helped found a relationship between partners beyond merely a sexual one.[12] However, this theory has since been generally disregarded due to the discovery that other primates, such as orangutans, routinely mate in the face-to-face position even though the females do not have prominent breasts.

The female gelada monkey in estrus presents swollen breasts to signal her reproductive status to the males. Based on that, evolutionary psychologists suggest that human female breasts may have evolved to permanently indicate to human males that the female is apt for reproduction.

History

In European pre-historic societies, sculptures of female figures with pronounced or highly exaggerated breasts were common. A typical example is the so-called Venus of Willendorf, one of many Paleolithic Venus figurines with ample hips and bosom. Artifacts such as bowls, rock carvings and sacred statues with breasts have been recorded from 15,000 BC up to late antiquity all across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Many female deities representing love and fertility were associated with breasts and breast milk. Figures of the Phoenician goddess Astarte were represented as pillars studded with breasts. Isis, an Egyptian goddess who represented, among many other things, ideal motherhood, was often portrayed as suckling pharaohs, thereby confirming their divine status as rulers. Even certain male deities representing regeneration and fertility were occasionally depicted with breast-like appendices, such as the river god Hapy who was considered to be responsible for the annual overflowing of the Nile. Female breasts were also prominent in the Minoan civilization in the form of the famous Snake Goddess statuettes. In Ancient Greece there were several cults worshipping the "Kourotrophos", the suckling mother, represented by goddesses such as Gaia, Hera and Artemis. The worship of deities symbolized by the female breast in Greece became less common during the first millennium. The popular adoration of female goddesses decreased significantly during the rise of the Greek city states, a legacy which was passed on to the later Roman empire.[13]

During the middle of the first millennium BC, Greek culture experienced a gradual change in the perception of female breasts. Women in art were covered in clothing from the neck down, including female goddesses like Athena, the patron of Athens who represented heroic endeavor. There were exceptions: Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was more frequently portrayed fully nude, though in postures that were intended to portray shyness or modesty, a portrayal that has been compared to modern pin ups by historian Marilyn Yalom.[14] Although nude men were depicted standing upright, most depictions of female nudity in Greek art occurred "usually with drapery near at hand and with a forward-bending, self-protecting posture".[15] A popular legend at the time was of the Amazons, a tribe of fierce female warriors who socialized only with men for procreation and even removed one breast to become better warriors. The legend was a popular motif in art during Greek and Roman antiquity and served as an antithetical cautionary tale.

Cultural status

In religion

Some religions afford the breast a special status, either in formal teachings or in symbolism. Islam forbids public exposure of the female breasts.[16] In Christian iconography, some works of art depict women with their breasts in their hands or on a platter, signifying that they died as a martyr by having their breasts severed; one example of this is Saint Agatha of Sicily. In Silappatikaram, Kannagi tears off her left breast and flings it on Madurai, cursing it, causing a devastating fire.

In practice

Breasts are secondary sex characteristics and sexually sensitive. Bare female breasts can elicit heightened sexual desires from men in certain cultures. Cultures that associate the breast primarily with sex (as opposed to with breastfeeding) tend to designate bare breasts as indecent, and they are not commonly displayed in public, in contrast to male chests. Other cultures view female toplessness as acceptable, and in some countries women have never been forbidden to bare their chests; in some African cultures, for example, the thigh is highly sexualised and never exposed in public, but the breast is not taboo. Opinion on the exposure of breasts often depends on the place and context, and in some Western societies exposure of breasts on a beach may be acceptable, although in town centres, for example, it is usually considered indecent. In some areas the prohibition against the display of a woman's breasts only restricts exposure of the nipples.

Women in some areas and cultures are approaching the issue of breast exposure as one of sexual equality, since men (and pre-pubescent children) may bare their chests, but women and teenage girls are forbidden. In the United States, the topfree equality movement seeks to redress this imbalance. This movement won a decision in 1992 in the New York State Court of Appeals—“People v. Santorelli”, where the court ruled that the state's indecent exposure laws do not ban women from being barebreasted. A similar movement succeeded in most parts of Canada in the 1990s. In Australia and much of Europe it is acceptable for women and teenage girls to sunbathe topless on some public beaches and swimming pools, but these are generally the only public areas where exposing breasts is acceptable.

When breastfeeding a baby in public, legal and social rules regarding indecent exposure and dress codes, as well as inhibitions of the woman, tend to be relaxed. Numerous laws around the world have made public breastfeeding legal and disallow companies from prohibiting it in the workplace. Yet the public reaction at the sight of breastfeeding can make the situation uncomfortable for those involved.

Clothing

Since the breasts are flexible, their shape may be affected by clothing, and foundation garments in particular. A brassiere (bra) may be worn to give additional support and to alter the shape of the breasts. There is some debate over whether such support is desirable. A long term clinical study showed that women with large breasts can suffer Myalgia, or shoulder pain as a result of bra straps,[17] although a well fitting bra should support most of the breasts' weight with proper sized cups and back band rather than on the shoulders.

Plastic surgery

Plastic surgical procedures of the breast include those for both cosmetic and reconstructive surgery indications. Some women choose these procedures as a result of the high value placed on symmetry of the human form, and because they identify their femininity and sense of self with their breasts.

After mastectomy (the surgical removal of a breast, usually to treat breast cancer) some women undergo breast reconstruction, either with breast implants or autologous tissue transfer, using fat and tissues from the abdomen (TRAM flap) or back (latissiumus muscle flap).

Breast reduction surgery is a common procedure which involves removing excess breast tissue, fat, and skin with repositioning of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC). Cosmetic procedures include breast lifts (mastopexy), breast augmentation with implants, and procedures that combine both elements. Implants containing either silicone gel or saline are available for augmentation and reconstructive surgeries. Surgery can repair inverted nipples by releasing ductal tissues which are tethering. Breast lift with or without reduction can be part of upper body lift after massive weight loss body contouring.

Any surgery of the breast carries with it the potential for interfering with future breastfeeding,[18][19][20] causing alterations in nipple sensation, and difficulty in interpreting mammography (xrays of the breast). A number of studies have demonstrated a similar ability to breastfeed when breast reduction patients are compared to control groups where the surgery was performed using a modern pedicle surgical technique.[21][22][23][24] Plastic surgery organizations have generally discouraged elective cosmetic breast augmentation surgery for teenage girls as the volume of their breast tissue may continue to grow significantly as they mature and because of concerns about understanding long-term risks and benefits of the procedure. Breast surgery in teens for reduction of significantly enlarged breasts or surgery to correct hypoplasia and severe asymmetry is considered on a case by case basis by most surgeons.

Health

Breast health factors

Factors that appear to be implicated in decreasing the risk of, or early diagnosis of breast cancer are regular breast examinations by health care professionals, regular mammograms, self examination of breasts, healthy diet, and exercise to decrease excess body fat. Healthy diet appears to reduce the risk of breast cancer, and includes limiting dietary fat, eating a balanced diet that includes plenty of nutrients, and dietary fibre such as are found in fruits and vegetables, and restricting intake of alcohol to a maximum of two drinks per day or less.[25]

Breast disease

Numerous abnormal breast conditions or diseases are documented. A majority are not cancerous.

See also

- Brassiere

- Breast bondage

- Breast cancer

- Breast fetishism

- Cleavage (breasts)

- Intimate part

- Mammary intercourse

- Milk line

- Multiple breast syndrome

Notes

- ^ mammal - Definitions from Dictionary.com

- ^ Introduction to the Human Body, fifth ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2001. 560.

- ^ a b Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, Hartmann PE (2005). "Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging". J. Anat. 206 (6): 525–34. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00417.x. PMC 1571528. PMID 15960763.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.mckinley.uiuc.edu/Handouts/female_function_dysfunction.html".

- ^ Boutros S, Kattash M, Wienfeld A, Yuksel E, Baer S, Shenaq S (1998). "The intradermal anatomy of the inframammary fold". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102 (4): 1030–3. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809040-00017. PMID 9734420.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greenbaum AR, Heslop T, Morris J, Dunn KW (2003). "An investigation of the suitability of bra fit in women referred for reduction mammaplasty". Br J Plast Surg. 56 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00122-X. PMID 12859918.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C.W. Loughry; et al. (1989). "Breast volume measurement of 598 women using biostereometric analysis". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 22 (5): 380–385. doi:10.1097/00000637-198905000-00002. PMID 2729845.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c Bentley, Gillian R. (2001). "The Evolution of the Human Breast". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 32 (38): 30. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1033.

- ^ secondary sex characteristics

- ^ Anders Pape Møller; et al. (1995). "Breast asymmetry, sexual selection, and human reproductive success". Ethology and Sociobiology. 16 (3): 207–219. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00002-3.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Sir Richard Burton's English translation of Kama Sutra

- ^ Morris (1967), pp. 64-68.

- ^ Yalom (1998) pp. 9-16; see Eva Keuls (1993), Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens for a detailed study of male-dominant rule in ancient Greece.

- ^ Yalom (1998), p. 18.

- ^ Hollander (1993), p. 6.

- ^ “They shall cover their chests” or “they should draw their khimar (veils) over their bosoms”, depending on the translation, Quran (24:31). Available online

- ^ Ryan EL (2000). "Pectoral girdle myalgia in women: a 5-year study in a clinical setting". Clin J Pain. 16 (4): 298–303. doi:10.1097/00002508-200012000-00004. PMID 11153784.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Neifert, M (1990). "The influence of breast surgery, breast appearance and pregnancy-induced changes on lactation sufficiency as measured by infant weight gain". Birth. 17 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1990.tb00007.x. PMID 2288566.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "FAQ on Previous Breast Surgery and Breastfeeding". La Leche League International. 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ West, Diana. "Breastfeeding After Breast Surgery". Australian Breastfeeding Association. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ Cruz-Korchin N, Korchin L (2004). "Breast-feeding after vertical mammaplasty with medial pedicle". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 114 (4): 890–4. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000133174.64330.CC. PMID 15468394.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brzozowski D, Niessen M, Evans HB, Hurst LN (2000). "Breast-feeding after inferior pedicle reduction mammaplasty". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105 (2): 530–4. doi:10.1097/00006534-200002000-00008. PMID 10697157.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Witte, PM (2004-06-26). "Successful breastfeeding after reduction mammaplasty". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 148 (26): 1291–93. PMID 15279213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kakagia, D (2005-10). "Breastfeeding after reduction mammaplasty: a comparison of 3 techniques". Ann Plast Surg. 55 (4): 343–45. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000179167.18733.97. PMID 16186694.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mctiernan, Anne, M.D., Ph.D., Gralow, Julie.M.D., Talbot, Lisa, MPH. Breast Fitness: An OptimalExercise and Health Plan for Reducing Your Risk of Breast Cancer. St Martin's Griffin, October, 2001. pg 135-137.

References

- Hollander, Anne Seeing through Clothes. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1993 ISBN 0-52008-231-1

- Morris, Desmond The Naked Ape: a zoologist's study of the human animal Bantam Books, Canada. 1967

- Yalom, Marilyn A History of the Breast. Pandora, London. 1998 ISBN 0-86358-400-4