Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

Alansplodge (talk | contribs) |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

*::::Also, also, as I look at some information in [[Kola Superdeep Borehole]], even within the crust, when you get down past about 10 km, the temperature is hot enough to boil water. You'd probably bake to death before you even hit the bottom. --[[User:Jayron32|<span style="color:#009">Jayron</span>]][[User talk:Jayron32|<b style="color:#090">''32''</b>]] 16:36, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

*::::Also, also, as I look at some information in [[Kola Superdeep Borehole]], even within the crust, when you get down past about 10 km, the temperature is hot enough to boil water. You'd probably bake to death before you even hit the bottom. --[[User:Jayron32|<span style="color:#009">Jayron</span>]][[User talk:Jayron32|<b style="color:#090">''32''</b>]] 16:36, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

||

*:::::Also, also, also, consider that [[Caisson disease]], aka "the Bends", is a real possibility at depths of that level, given the massive increase in air pressure you are likely to experience. --[[User:Jayron32|<span style="color:#009">Jayron</span>]][[User talk:Jayron32|<b style="color:#090">''32''</b>]] 16:52, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

*:::::Also, also, also, consider that [[Caisson disease]], aka "the Bends", is a real possibility at depths of that level, given the massive increase in air pressure you are likely to experience. --[[User:Jayron32|<span style="color:#009">Jayron</span>]][[User talk:Jayron32|<b style="color:#090">''32''</b>]] 16:52, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

||

::::::a decompression accident would be a problem on the way back up, oxygen toxicity due to its high partial pressure would get you on the way down. |

|||

*:::::I always thought that (assuming you didn't fill most of it with air compressed to specific gravities >>1) some spectacular implosion at at least c. the speed of sound of each Earth layer would happen, as most of the cylinder surface would have pressure of 1 to 3.6 million atmospheres. How much magma gas would come out of solution from this brief exposure to the hole's lower pressure, and how dramatic of an eruption that could cause I don't know. Would magma not reach the entrance because mantle is denser than continental crust or would it barely leak out or spurt 100 meters high or something stronger and less Hawaiian? How big or small would the earthquake be? How far from the hole would crack? And if it's wide enough for bouncing off the edge to not come first then how far could you fall before things get bad? [[User:Sagittarian Milky Way|Sagittarian Milky Way]] ([[User talk:Sagittarian Milky Way|talk]]) 23:32, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

*:::::I always thought that (assuming you didn't fill most of it with air compressed to specific gravities >>1) some spectacular implosion at at least c. the speed of sound of each Earth layer would happen, as most of the cylinder surface would have pressure of 1 to 3.6 million atmospheres. How much magma gas would come out of solution from this brief exposure to the hole's lower pressure, and how dramatic of an eruption that could cause I don't know. Would magma not reach the entrance because mantle is denser than continental crust or would it barely leak out or spurt 100 meters high or something stronger and less Hawaiian? How big or small would the earthquake be? How far from the hole would crack? And if it's wide enough for bouncing off the edge to not come first then how far could you fall before things get bad? [[User:Sagittarian Milky Way|Sagittarian Milky Way]] ([[User talk:Sagittarian Milky Way|talk]]) 23:32, 4 April 2022 (UTC) |

||

:::::::Even worse than gravitational irregularities is the [[Coriolis force]] sending you off cource. Unless you travel exactly [[Pole to Pole]]. [[User:PiusImpavidus|PiusImpavidus]] ([[User talk:PiusImpavidus|talk]]) 10:15, 5 April 2022 (UTC) |

:::::::Even worse than gravitational irregularities is the [[Coriolis force]] sending you off cource. Unless you travel exactly [[Pole to Pole]]. [[User:PiusImpavidus|PiusImpavidus]] ([[User talk:PiusImpavidus|talk]]) 10:15, 5 April 2022 (UTC) |

||

Revision as of 11:33, 5 April 2022

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

March 29

Name of a common weather pattern

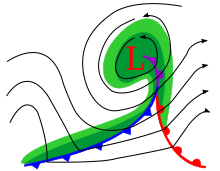

In the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes, where I live, it is quite common that a low-pressure area is accompanied by a warm front extending southeast and a cold front extending southwest. The diagram shows an example: in this case the (blue) cold front has caught up with the (red) warm front to form a section of (purple) occluded front, but that's not important to my question. If the low passes north of us, we get both fronts in rapid succession, causing a short period of warmer weather, lasting maybe a day or so. For example, look at maximum temperatures recorded here in Toronto this month, on the left side of this table: on March 6, the temperature spiked to 16°C, much higher than the day before or after. And there was a similar but less intense spike on March 24.

My question is simply this: Is there a name for this phenomenon, either the underlying phenomenon of a moving low with two fronts extending from it, or the resulting rapid two-way temperature change? --184.144.97.125 (talk) 11:46, 29 March 2022 (UTC)

- This is a cyclone, more specifically an Extratropical cyclone. The red and blue lines represent warm fronts and cold fronts, which are literally the front edge of an air mass whose temperature differs significantly from the neighboring air masses. --Jayron32 11:58, 29 March 2022 (UTC)

- For completeness, in the occluded front the cold front has caught up with the warm front and is driving underneath it. The marked front is similar to the bottom of a V shaped valley higher in the atmosphere as the warm air is pushed upwards. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 12:07, 29 March 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, I know, "cyclone" is another name for a low-pressure area. I'm talking about the cyclone together with two fronts, the whole thing moving along with the prevailing winds to create a tongue of warmer air that gives a day

orof warmer weather. --184.144.97.125 (talk) 01:17, 30 March 2022 (UTC)- In the northern hemisphere the polar front marks the division between cold polar air and warm, moist air coming from the south. A disturbance in the upper atmosphere allows some warm air to start to push north which creates a toungue with cold air behind it. As the low develops the coriolis force ensures that the rotation is anti-clockwise and that brings the cold air down behind the low. You can always tell where things are: Buys Ballot's Law states that if you stand with the wind behind you, the Low is on your Left. The wind will angle about 10-15 degrees inwards from the isobars over the sea, and as much as 30° over land. The cold air travels significantly faster than the warm, and so the cold front eventually catches up with the warm, lifts it (occluded front) and the low fills and dissipates. The rotating winds around a low are called a cyclone (think: cycle). Cyclones are always associated with fronts, there is no special name for a cyclone with fronts anymore than there is a special name for people with fronts! Martin of Sheffield (talk) 08:42, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, I know, "cyclone" is another name for a low-pressure area. I'm talking about the cyclone together with two fronts, the whole thing moving along with the prevailing winds to create a tongue of warmer air that gives a day

- For completeness, in the occluded front the cold front has caught up with the warm front and is driving underneath it. The marked front is similar to the bottom of a V shaped valley higher in the atmosphere as the warm air is pushed upwards. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 12:07, 29 March 2022 (UTC)

Earth is expelled from solar system, how far away from the Sun can we maintain the same global temperature by injecting greenhouse gases into the atmospere?

Suppose that due to some freak event like an encounter with a rogue planet that enters our solar system, the Earth is propelled out of the solar system. Temperatures will then drop as we get farther away from the Sun, But we can try to compensate for that by injecting greenhouse gasses such as CO2, methane into the atmosphere. There exist extremely powerful greenhouse gases like HFC-23 that have about 12,000 times the global warming potential compared to CO2. How far away from the Sun can the current ambient temperature be maintained by injecting these sorts of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere? Count Iblis (talk) 19:26, 29 March 2022 (UTC)

- Maybe you will be able to figure it out yourself after reading Inverse-square law. 178.208.99.186 (talk) 07:34, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- At a first approximation, no further (and probably rather less less) than the outer extent of the Sun's Circumstellar habitable zone (aka "Goldilocks zone"), which is based on atmospheric compositions compatible with life (of any kind) rather than Earth's current exact atmospheric composition and biosphere.

- As you will see (Section 2.1), there are a range of estimates of what the furthest extent of the zone (in our Solar system) is, which the article tabulates: the estimates range from 1.004 to 10 AU, but the latter predicates a high-pressure hydrogen atmosphere probably unobtainable by any amount of terrestrial planetary engineering and incompatible with virtually all terrestrial life (perhaps some microbes could survive in it).

- (I notice with amusement that the next most generous estimate of 3.0 AU was made by Martyn J. Fogg, an old friend of mine.)

- While this doesn't directly address your question, it may give you some parameters within which to work and some references for further investigation. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.209.233.48 (talk) 10:27, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- A similar idea occurs in the sci-fi novel Project Hail Mary: the sun's output is temporarily reduced by (something alien), and humans avoid a new and permanent Ice Age by releasing large amounts of methane into the atmosphere, countering the reduction in solar energy coming in by reducing the amount of energy radiated out. If you want to do computations, probably best to start from something like Earth's energy budget. —Kusma (talk) 10:58, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Could such gases be introduced to the atmosphere in quantities sufficient to hold in enough heat without reaching levels inimical to human life? --User:Khajidha (talk) (contributions) 11:29, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- That's the rub, isn't it? Methane and CO2 and other greenhouse gases are not necessarily inert with regards to life on earth. High enough CO2 levels, for example, lead to Hypercapnia in animals. --Jayron32 12:13, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Not to mention the forces needed to remove the earth from its orbit are likely to make the question of human reaction moot, due to our going extinct from various effects. --User:Khajidha (talk) (contributions) 12:29, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- The force that keeps the Earth in its orbit is something like 35 × 1021 N. This does not appear to bother us much. --Lambiam 15:29, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, but the additional forces needed to overcome that force over a short enough time for us to notice it would likely cause accelerations that are unfriendly to our soft internal organs. --Jayron32 15:44, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- If a planet with a mass like Jupiter passes by the Earth at a distance of 360 000 000 m (360 000 km), it will exert a gravitational force of about 5.83 × 1024 N on the Earth, which will result in an acceleration of the Earth with its inhabitants of less than 0.1 g. This is survivable. But if the hyperbolic trajectory of the rogue planet near perigee comes close to the Earth's orbit, while the Earth is near at that time, this mild acceleration over a longer period of time may be enough to result in a significantly altered orbit. Compare the slingshot effect. --Lambiam 22:56, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- There's a mismatch in your calculation. The force and acceleration are correct if a Jupiter-mass planet is 360 thousand km from Earth, which is about the same as the Earth-Moon distance. At 360 million km, both are smaller by a factor of one million. (The actual closest approach of Jupiter to Earth is about 588 million km.) --Amble (talk) 23:34, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Thanks, now corrected. --Lambiam 13:09, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- There's a mismatch in your calculation. The force and acceleration are correct if a Jupiter-mass planet is 360 thousand km from Earth, which is about the same as the Earth-Moon distance. At 360 million km, both are smaller by a factor of one million. (The actual closest approach of Jupiter to Earth is about 588 million km.) --Amble (talk) 23:34, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Gravity acting on the entire human body will cause the same acceleration everywhere and therefore no forces in the human body. The large acceleration is no problem. There could be a problem with tidal forces, but those are more likely to rip the Earth apart than to rip humans apart. But then, ripping the Earth apart would be pretty bad for those humans living there. PiusImpavidus (talk) 12:22, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Extreme tidal forces – much stronger than a mere planet can give rise to – can lead to spaghettification, which would be a serious health problem. --Lambiam 10:59, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- I've wondered about that. It's not like stretching the body though, the structures, cells, atoms and even fundamental particles and fields would be distorted in the same manner. Would the putative astronaut actually perceive anything at the event horizon? Martin of Sheffield (talk) 11:40, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, tidal forces cause a real, physical stretching and squashing that you would feel. This is what heats the interiors of Io and Europa, and the spaghettification near a black hole is just a more extreme instance of the same physical effect. But it is not connected to the event horizon in particular. See Spaghettification#Inside_or_outside_the_event_horizon. If you fell through the event horizon of a supermassive black hole, as far as we know, you would not feel anything special, and the tidal forces would still be very small at that point. Note that the equivalence principle only applies locally; a body feels tidal forces when it is too big to count as "local" in some setting.--Amble (talk) 16:20, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- I've wondered about that. It's not like stretching the body though, the structures, cells, atoms and even fundamental particles and fields would be distorted in the same manner. Would the putative astronaut actually perceive anything at the event horizon? Martin of Sheffield (talk) 11:40, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- Extreme tidal forces – much stronger than a mere planet can give rise to – can lead to spaghettification, which would be a serious health problem. --Lambiam 10:59, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- If a planet with a mass like Jupiter passes by the Earth at a distance of 360 000 000 m (360 000 km), it will exert a gravitational force of about 5.83 × 1024 N on the Earth, which will result in an acceleration of the Earth with its inhabitants of less than 0.1 g. This is survivable. But if the hyperbolic trajectory of the rogue planet near perigee comes close to the Earth's orbit, while the Earth is near at that time, this mild acceleration over a longer period of time may be enough to result in a significantly altered orbit. Compare the slingshot effect. --Lambiam 22:56, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, but the additional forces needed to overcome that force over a short enough time for us to notice it would likely cause accelerations that are unfriendly to our soft internal organs. --Jayron32 15:44, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- The force that keeps the Earth in its orbit is something like 35 × 1021 N. This does not appear to bother us much. --Lambiam 15:29, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Not to mention the forces needed to remove the earth from its orbit are likely to make the question of human reaction moot, due to our going extinct from various effects. --User:Khajidha (talk) (contributions) 12:29, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- That's the rub, isn't it? Methane and CO2 and other greenhouse gases are not necessarily inert with regards to life on earth. High enough CO2 levels, for example, lead to Hypercapnia in animals. --Jayron32 12:13, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Thermal equilibrium is reached when the incoming heat from solar radiation equals the outgoing heat radiated by Earth into space. The former is easily computed as a function of the distance to the Sun. The latter depends on the temperature distribution, the composition of the atmosphere, and the albedo (mainly but not only a matter of cloud cover). Without formulas and tables of constants for computing this, it is not possible to determine the answer to the hypothetical question. --Lambiam 15:42, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- It's really only the surface and atmosphere that will cool down on a relevant timescale. The interior can stay quite hot for a long time. If you can surround the planet with enough layers of multi-layer insulation, the Earth's internal heat budget will be enough to keep up a cozy temperature at the surface. Of course, it will still be dark and there will be nothing to eat. --Amble (talk) 16:52, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Hard to give an exact answer, but the distance would be of the order of one astronomical unit. Given the speed at which the Earth has to move to be ejected from the solar system, that would only take months, so no time to add enough greenhouse gas to the atmosphere to make a significant difference. PiusImpavidus (talk) 12:22, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

March 30

Cat Rection to A-Minor Chord

Are there any references about cat reactions to certain chords? There is a cat here that drops low, lays her ears back, and starts chirping when a A-minor chord is played, but does not react to any other chord. 97.82.165.112 (talk) 18:02, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- I'm not aware that cats have perfect pitch, but one never knows. There are a few studies listed here that discuss cat response to music in general, but I can find nothing on specific chords. I will note that individual cat psychology is likely to be as individualized as humans are; as such the fact that your cat reacts in a specific way to a specific stimulus is certainly no different than a specific human who may have a reaction to a stimulus, whether a specific sound, taste, odor, etc. Just as a person may have a unique reaction to a specific stimulus that other people do not, that doesn't mean that humans in general react that way. --Jayron32 18:26, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

Plourdosteidae

I recently made an article for Compagopiscis, and was going to add a taxobox (someone else ended up doing it). When I got to the family part, I was stuck. One website said that Compagopiscis was in Plourdosteidae. I looked at the page for Plourdosteus, and it said it was in Panxiosteidae. So I looked it up and found that Plourdosteidae was an invalid taxon and that Plourdosteus was, in fact, in Panxiosteidae. But another website said that Compagopiscis was not in Panxiosteidae.

So basically, what I'm asking is-

What family is Compagopiscis in?

(Somebody else added a taxobox and put it as Plourdosteidae, but how can it be a valid taxon if its namesake isn't even in it?)

Asparagusus (talk) 18:25, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- You might find Wikipedia talk:WikiProject Palaeontology a better location for asking this question. Mikenorton (talk) 20:57, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Not a resolution but a piece of the puzzle. The main contribution of this article is to argue that fossil remains of Compagopiscis croucheri and Gogopiscis gracilis actually represent a single species occupying the monospecific genus Compagopiscis. While it places the genus in the infraorder Brachythoraci, it does not identify a family. However, the authors do write that the presence of eight morphological characteristics in the compagopiscids, which they proceed to specify, can be used to easily separate C. croucheri from the superficially similar Plourdosteidae. So, in the judgement of the authors, assigning the genus to the Plourdosteidae is wrong. It should be understood that in general the systematic taxonomy of palaeontological species is often conjectural and may be subject to reordering as new evidence is found in the geological record. --Lambiam 22:25, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- This article positions Compagopiscis in the superfamily Incisoscutoidea, together with Incisoscutum and the Camuropiscidae. (Currently, Wikipedia treats Incisoscutoidea and Camuropiscidae as sister families in the superfamily Coccosteoidea.) --Lambiam 10:47, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

Dissimilar woods

I've been following the reconstruction of Tally Ho (yacht), and they seem to combine very different kinds of timber without any problem or even thought. For dissimilar metals, especially in a marine environment, this would, of course, lead to galvanic corrosion and probably reduce the structure to different kinds of rust quickly. Are there any similar constraints for wood? --Stephan Schulz (talk) 19:51, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Yes, it's well worth a watch! YouTube link nagualdesign 14:12, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- According to a woodworker at Elite Custom Woodworks in Greenville, SC, once woods are dried, you can and should mix them. Having different woods makes custom woodworking appear much higher quality. If you do this when the wood is not fully cured (which I take to mean fully dry), it can eventually warp and cause problems. But, there is no reaction between one wood and another. Then, according to a professor of dendrology at Clemson, all tree wood, regardless of species, are almost completely cellulose and hemicellulose. Using that information, we have a book, Handbook of Wood Chemistry and Wood Composites by Roger Rowell that states the same thing. Tree wood is just cellulose and hemicellulose with minor deposits of sugar, starch, and pectin. He references Wood and Cellulose Science by Alfred Stamm, who goes on to state that the primary difference between woods is the accessibility of the cellulose. Higher accessibility leads to faster rotting from water and easier access for parasites. If that doesn't help, I can look further. I didn't know much about wood chemistry before I started calling around. 97.82.165.112 (talk) 21:00, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Serious warping may also occur with constructions using just one kind of timber, if it is insufficiently dried. Ideally, it should not be 100% dry; it should instead match the average humidity of its future environment, so that it will remain in a relatively stable equilibrium with that environment. --Lambiam 23:02, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- See Church of St Mary and All Saints, Chesterfield. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 09:33, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Wow. "lack of skilled workers [...]; the use of insufficient cross bracing and 'green timber' [...] the 17th-century addition of 33 tons of lead sheeting covering the spire, resting on 14th-century bracing not designed to carry such weight". I always liked wood as a material, and this is one example where so much went wrong, and it still holds up (mostly) under pressure. I wonder what will happen in 2318, when they put 33 tons of weight on something "not designed to carry that load" today. If anything from today is even standing in 300 years.... --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:05, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- See Church of St Mary and All Saints, Chesterfield. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 09:33, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Serious warping may also occur with constructions using just one kind of timber, if it is insufficiently dried. Ideally, it should not be 100% dry; it should instead match the average humidity of its future environment, so that it will remain in a relatively stable equilibrium with that environment. --Lambiam 23:02, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- Here's a building made from 10,000 different kinds of wood. (I only found this because Lambiam used the term "neo-grotesque" on the language desk, so I searched for a modernist grotto to see what kind of writing might be on it.) Card Zero (talk) 13:58, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- "...match the average humidity of its future environment...". Tally Ho is (or will eventually be again) an ocean-going yacht; should it therefore be constructed of very wet timber?

- I also note (as an avid follower of Leo's videos) that he takes great pains to avoid allowing fresh water to touch his timber, but is unconcerned about the quantities of salt water in which it will inevitably be soaked. Does that have a bearing on how dry his timber should be? --Verbarson talkedits 18:12, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- I expect he intends to use yacht varnish before committing it to the deep. Alansplodge (talk) 20:49, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

Any credible source on Polonium-210 production, export figures?

Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko has these two not clearly sourced sentences: "About 85 grams (450,000 Ci) are produced by Russia annually for research and industrial purposes. According to Sergei Kiriyenko, the head of Russia's state atomic energy agency, RosAtom, around 0.8 grams per year is exported to U.S. companies through a single authorized supplier.". If I got it rigth, the source "Supplementary Report by Norman David Dombey" suggests some confusion between 8g/month and 0.8g/month, where the larger figure wasn't/isn't much credible, but was reported all over the place (e.g. Polonium, $22.50 Plus Tax, where Kiriyenko is mentioned). Polonium-210 currently cites a source for 8g/month (not sure if exports increased that much in these years). To add to the confusion 0.8g/month is not that far from 8g/year. Also I'm not sure if the same confusion applies to the production figures or if there is some other article worth double-checking. 109.119.244.192 (talk) 22:28, 30 March 2022 (UTC)

- This should be the mentioned Reuters article and this (archive) the one from Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Reuters talks about Sergey Kiriyenko, while RG features Ilkaev and mentions some previous talk about 8 g/month, so it's possible that Reuters and others refer to some other article. Kiriyenko is't exactly a physicist. Both seem to be more about production than export or export to the US. 109.119.244.192 (talk) 02:46, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Actually I found this citing Interfax instead of RG (Kiriyenko, 8g/month, all export to the US, published before Reuters). The previously linked RG is later than both, so it kind of make sense (but is mentioned in the "Supplementary Report" as being from october, not from december). I still have no idea what would be a credible export amount. 109.119.244.192 (talk) 04:15, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Ransac talks about 100 preprations "B" monthly. 8g/100*4500 Ci/g gives 360 Ci per preparation. In 1978 the limit for transport in type A packages was 200 Ci, type B packages would still allow more [1]. Assuming 0.1 Ci per static eliminator, 8g would be enough for 8g*4500Ci/g÷0.1Ci=360,000 units. 176.247.189.17 (talk) 07:33, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Looks like Kirienko was correcting a previous statement about 8g/year [2], so it was really quite messy.176.247.143.235 (talk) 15:24, 3 April 2022 (UTC)

- Ransac talks about 100 preprations "B" monthly. 8g/100*4500 Ci/g gives 360 Ci per preparation. In 1978 the limit for transport in type A packages was 200 Ci, type B packages would still allow more [1]. Assuming 0.1 Ci per static eliminator, 8g would be enough for 8g*4500Ci/g÷0.1Ci=360,000 units. 176.247.189.17 (talk) 07:33, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

March 31

Television antennae

What kind of metal(s) are television antennae typically made of? I was unable to find details in the article. Thanks. Martinevans123 (talk) 13:12, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Almost always aluminum. 97.82.165.112 (talk) 13:37, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Or copper? Searching for this just gets me lots of non-authoritative forum discussions. Card Zero (talk) 13:43, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Every television antenna for sale at our Home Depot, Lowes, and WalMart is aluminum. They have copper wires to connect the antenna, but the antenna itself is aluminum. Copper quickly corrodes, restricting the ability to pick up a good signal. If, theoretically, you had a copper antenna in an enclosed inert environment, that would work fine. That isn't normal. 97.82.165.112 (talk) 19:12, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Copper costs more than aluminium. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 20:22, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- I think a little patina wouldn't matina. Here's an actual source, of a kind, asking "Why are Antenna’s Made of Aluminum?" It's annoying how hard it can be to find a source for the obvious, sometimes. Ideally I'd like one from a well-established publication, without a grocer's apostrophe in the title. I know TV antennae are always aluminum, but I'm not a reliable source. Lots of instructions for home-made (indoor) antennae say to use copper, and at least one person's outdoor antenna was copper, but that seemed to belong to a radio ham (before it blew down in the wind). Card Zero (talk) 20:48, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Every television antenna for sale at our Home Depot, Lowes, and WalMart is aluminum. They have copper wires to connect the antenna, but the antenna itself is aluminum. Copper quickly corrodes, restricting the ability to pick up a good signal. If, theoretically, you had a copper antenna in an enclosed inert environment, that would work fine. That isn't normal. 97.82.165.112 (talk) 19:12, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Or copper? Searching for this just gets me lots of non-authoritative forum discussions. Card Zero (talk) 13:43, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- An antenna is a kind of electrical conductor. The same science and engineering applies to them as does to conductors used for carrying "power". Of course, in your typical receiving antenna, the power involved is small, so no concern about things like electrical fires. As that article describes, the materials for your everyday conductors are copper and aluminum. Aluminum has the advantages of lower cost and greater resistance to the environment, both of which motivate its use in antennas as well as long-distance electrical wiring. Copper has a higher conductivity, but also costs more and reacts with "the elements", which means copper conductors are usually insulated. --47.147.118.55 (talk) 03:52, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- It reacts to form a coating of verdigris. So then you have a green antenna, which still works. Card Zero (talk) 07:13, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- It should also be noted that Aluminum also forms a coating, though because it doesn't have such a striking difference in color, this goes unnoticed. Pure aluminum is almost white; while most aluminum you see has a darker grey oxidation coating on it. Aluminum is a very reactive metal, the paradox of aluminum is that it is a very reactive metal (only slightly less reactive than the alkali metals and alkaline earth metals), see Reactivity series to see aluminums relatively high positioning (especially compared to copper, which is much lower on the series), which is highly corrosion-resistant. However, the layer of aluminum oxide that forms is a) very thin b) adheres strongly to the surface of aluminum and c) is basically impervious, preventing further corrosion. See here: [3]. What makes copper corrosion so much more noticeable is that copper compounds are generally blue or blue-green in color; making a striking difference between the metal and the corrosion. Aluminum basically just turns a slightly darker shade of grey, so it doesn't really stand out. --Jayron32 15:59, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- Aluminium has another advantage over copper. Copper has a low melting point, so if stolen is easily to melt down with minimal facilities; aluminium on the other hand requires much more elaborate equipment, which an individual or a dishonest small-scale scrap-metal dealer (at least in the UK) is unlikely to have. If home TV aerials were typically made of copper, they would be stolen frequently: thefts of copper and bronze memorials, artworks and statues already occur.

- This is a live issue with mobile phone (cellphone) infrastructure in the UK, where typically in the summer months several more isolated sites per week (out of the ca. 100,000 in the country) have much of their copper cables stolen (a typical mast might have several hundred metres of cable). One of the measures used to discourage this is/was to replace them with aluminium cables (actually slightly more expensive, presumably for manufacturing reasons) and to place prominent notices at the site saying this has been done. (There are of course other measures – I'm not going to say what they are.)

- The effectiveness of this has been diminishing, however. After the UK's laws controlling scrap-metal dealers were tightened a few years ago, locally based thefts diminished, but there was a rise in the activity of pan-European gangs, who instead of taking their stolen cables to UK dealers ship it by the container-load to Eastern Europe, where large facilities with aluminium-handling equipment process it with impugnity.

- [Disclosure: my last job involved handling job reporting and client billing for a company carrying out emergency repairs on mobile phone aerial sites, some of which was necessitated by such thefts.] {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.209.233.48 (talk) 23:12, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- It should also be noted that Aluminum also forms a coating, though because it doesn't have such a striking difference in color, this goes unnoticed. Pure aluminum is almost white; while most aluminum you see has a darker grey oxidation coating on it. Aluminum is a very reactive metal, the paradox of aluminum is that it is a very reactive metal (only slightly less reactive than the alkali metals and alkaline earth metals), see Reactivity series to see aluminums relatively high positioning (especially compared to copper, which is much lower on the series), which is highly corrosion-resistant. However, the layer of aluminum oxide that forms is a) very thin b) adheres strongly to the surface of aluminum and c) is basically impervious, preventing further corrosion. See here: [3]. What makes copper corrosion so much more noticeable is that copper compounds are generally blue or blue-green in color; making a striking difference between the metal and the corrosion. Aluminum basically just turns a slightly darker shade of grey, so it doesn't really stand out. --Jayron32 15:59, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- It reacts to form a coating of verdigris. So then you have a green antenna, which still works. Card Zero (talk) 07:13, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

Entomological cabinet

I recently read in a book where a medical doctor of 1840 wished to dispose of his entomological cabinet comprising about two thousand species and nearly a thousand duplicates and it was offered for four hundred dollars. Trying to figure out what an "entomological cabinet" is and apparently it has something to do with insects. Would these be live insects? --Doug Coldwell (talk) 21:00, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- No, they would be neatly arranged in trays, impaled on pins. Here's another example big enough to see the pins and labels. Card Zero (talk) 21:07, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- @Card Zero: OOOOOh -> now I get it. Thanks for clearing that up and showing me examples.--Doug Coldwell (talk) 21:13, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- See no weevil, grok no weevil. Card Zero (talk) 21:17, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- @Card Zero: OOOOOh -> now I get it. Thanks for clearing that up and showing me examples.--Doug Coldwell (talk) 21:13, 31 March 2022 (UTC)

- Imagine the trouble you'd have maintaining your collection if it included live (briefly) examples of Doliana mayflies. Clarityfiend (talk) 03:49, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- Are these Greek mayflies dancing the συρτάκι and therefore hard to pin down, or did you mean Dolania? --Lambiam 10:20, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

- Aka D'ohlania. Clarityfiend (talk) 10:39, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Are these Greek mayflies dancing the συρτάκι and therefore hard to pin down, or did you mean Dolania? --Lambiam 10:20, 1 April 2022 (UTC)

April 2

Are there "natural freefall pose(s)"?

If you used a vertical wind tunnel to levitate a nude guy (or lady) and they went limp at random poses, orientations and spin axis velocities, directions and placements would they end up in a small set of stable poses? If there was a tunnel big enough to avoid getting too close to the edge (which there might not be). If the center of pressure is not at the center of mass of a simple object the COM tends to end up "down" but humans are more complicated, many joints and cheeks etc to potentially flap around in turbulence. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 03:27, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- The situation you describe is akin to "skydiving" aka free-fall parachuting, and in fact military (and possibly civilian) parachutists sometimes train in vertical wind tunnels (mentioned for example in the article High-altitude military parachuting), though not usually in the nude. I have also seen online videos of such devices used at recreational facilities, and know of instances of nude free-fall parachuting; mid-air 'coupling' may or may not have been attempted.

- I am not a parachutist myself, but my father has parachuted in a military context: my understanding is that if one does not actively control one's attitude with the correct limb positions, there is a strong possibility of going into a spin so violent as to render one helpless and possibly unconscious. This would be a bad thing in a wind tunnel, and even worse if skydiving. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.209.233.48 (talk) 04:03, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- So the natural state of a falling human is to spin indefinitely? I heard experts have skydove standing up for speed and maybe knife hands straight up too and they fell ≥60% faster than spread eagle, are they actively countering spin too? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 05:06, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Limbs being somewhat irregularly shaped, when in a spread-eagle posture each will contribute some torque with respect to the falling body's centre of mass. Since these will not sum up to exactly zero, this leads to spinning. The torque in a diving posture will be minimal. Tumbling can result from a random limp posture. --Lambiam 11:12, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- That's where I guessed the need to not let your spin get out of hand came from. If you can hold rigid maybe you can find a really balanced spread eagle that accelerates you rotationally very slowly. If the parachute jerk is unconformable or dangerous standing up and/or at 200mph (~4 times air resistance forces of spread eagle) then they'd probably slow back down and change to falling on their belly which seems a more advanced dive than the usual move to the belly by the time you're only a few tens of mph and adjust to rising resistance. I've seen intentional cool rolling into a spinning ball but film cut soon after the plane, maybe there's a sticking limbs out on the downspin side to kill rpm part they didn't show. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 18:42, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- I think in addition to the exact pose, the rigidity of the body would have a very significant influence on the behaviour of the falling body. That is, if you lock your body in any particular pose, your fall will be more controlled and less random than if the body is all loose. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 11:26, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- See also the Red Bull Stratos high altitude skydiving project with Austrian skydiver Felix Baumgartner, who jumped from a capsule 38 km up, but "An uncontrolled spin started within the first minute of the jump which could have been fatal, but it ended at 01:23 when Baumgartner regained stability". 46.102.221.177 (talk) 15:41, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Lucky guy. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 18:45, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- So it could be chaotic like the pendulum attached to pendulum thing? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 18:53, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

Dzhanibekov effect - I don't know, because the spinning T-handle in zero-gravity behaves in a regular pattern. But that's probably completely overwhelmed by air resistance effects, except for Baumgartner who was above most of the air at the time. Card Zero (talk) 20:13, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Doddy Hay (a test 'pilot' of the Martin-Baker ejector seat) writes of two American test 'pilots' doing similar tests from an altitude of 50,000 feet. Lt. Henry Neilsen found himself flat on his back and spinning so fast he was unable to perform the 'orthodox remedial action of rolling himself up into a ball in order to reduce the area of body-surface being presented to the air.' Fortunately, he eventually landed safely. His colleague, Capt. Ed Sperry, repeated the jump, and warned by his colleague's report began at the very start of free-fall 'to thresh around wildly with his arms and legs, kicking and punching in every direction. ... His random gymnastics served to break up the airflow' and he did not spin.[1] Possibly a static body will naturally tend to rotate in a specific direction, and if the position does not change, the rotation will only be reinforced; whereas a dynamic body will be pushed to turn in many different directions and have much less tendency to spin? It also suggests that at least one 'natural freefall pose' may be "spreadeagled and spinning".--Verbarson talkedits 22:52, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- The top speed of mach 1.25 was reached at 42 seconds, so similar force levels to regular skydiving by then. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 23:00, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- See also the Red Bull Stratos high altitude skydiving project with Austrian skydiver Felix Baumgartner, who jumped from a capsule 38 km up, but "An uncontrolled spin started within the first minute of the jump which could have been fatal, but it ended at 01:23 when Baumgartner regained stability". 46.102.221.177 (talk) 15:41, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Limbs being somewhat irregularly shaped, when in a spread-eagle posture each will contribute some torque with respect to the falling body's centre of mass. Since these will not sum up to exactly zero, this leads to spinning. The torque in a diving posture will be minimal. Tumbling can result from a random limp posture. --Lambiam 11:12, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- So the natural state of a falling human is to spin indefinitely? I heard experts have skydove standing up for speed and maybe knife hands straight up too and they fell ≥60% faster than spread eagle, are they actively countering spin too? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 05:06, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

References

- ^ Three great air stories. London: Collins. 1970. The Man in the Hot Seat Chap.9, pp.102–105. ISBN 0001923307.

Cordyline fruticosa

I inherited a Ti plant (Cordyline fruticosa) that I’ve been taking care of for about six years now in a large container. I estimate its age at about eight or nine. I have two choices going forward. One, I can continue keeping it in a container and making do, or two, attempt to plant it outside in a spacious area. There are benefits and drawbacks to both choices. My question has more to do with the botany of container raised plants. Since it has spent the majority of its life in a container (and never flowered so far, as I’m told it takes many years for that to happen), is it even worth considering moving it to open soil in a natural habitat conducive to its future free from the container? Furthermore, I am concerned that it has other problems. It has survived a spate of mites (which were recently destroyed by peppermint spray), but it may be currently suffering from a case of Phytophthora, in which case the literature recommends either destroying it or letting it live out its life. I would appreciate any insight into this dilemma. My understanding is that there is no known treatment for Phytophthora. Also, how do I, a layman, go about confirming and verifying Phytophthora is the correct diagnosis? Is there a simple test I can perform at home?Viriditas (talk) 09:27, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Phytophthora nicotianae: Leaves near the soil are water-soaked and have brown, irregular, zonate dead areas.[4]

- Phytophthora parasitica: Lesions form mainly on lower leaves close to the potting medium. They are initially water-soaked, brown, zonate areas with irregular margins.[5]

- These symptoms are also generically reported for Phytophthora. Here is something about controlling Phytophthora root rot, but it does not look very promising. Replanting outside may spread the pathogen to the soil and other plants. --Lambiam 10:53, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- Sorry if I wasn’t clear. I’m just not convinced that Phytopthora is the correct diagnosis. The plant looks really healthy right now, except for the lower leaves which seem to fit with the aforementioned diagnosis. Is there anything experimental I could try? I was thinking of changing out the soil in the container for starters. It feels like a shame to kill off a plant that is almost a decade old and shows no sign of dying soon. Based on my limited knowledge of plants, I don’t think the Phytophthora diagnosis is correct. To my untrained eye, it looks like a simple nutrient deficiency. How do I determine which nutrient it is lacking? In the hopes that I’m right, I just fed it a very small amount of 24(N), 8(P205), and 16(K20). Is this kind of plant food safe for a Ti plant, and how long will it take to notice any changes? Viriditas (talk) 20:56, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

- A preliminary diagnosis of Phytopthora is made based on the symptoms. For a more definitive confirmation, a lab test is needed. Apparently, there are DIY test kits.[6]

- Thanks. The good news is that 48 hours after adding the 24-8-16 nutrient solution, the plant is now thriving and producing the red streaks along the Ti leaf edges. I’ve never seen it this healthy. So it was a nutrient deficiency. I’ve also been told it’s important to use filtered water with Ti plants, so I’m going to try that next. Viriditas (talk) 21:31, 3 April 2022 (UTC)

- A preliminary diagnosis of Phytopthora is made based on the symptoms. For a more definitive confirmation, a lab test is needed. Apparently, there are DIY test kits.[6]

- Sorry if I wasn’t clear. I’m just not convinced that Phytopthora is the correct diagnosis. The plant looks really healthy right now, except for the lower leaves which seem to fit with the aforementioned diagnosis. Is there anything experimental I could try? I was thinking of changing out the soil in the container for starters. It feels like a shame to kill off a plant that is almost a decade old and shows no sign of dying soon. Based on my limited knowledge of plants, I don’t think the Phytophthora diagnosis is correct. To my untrained eye, it looks like a simple nutrient deficiency. How do I determine which nutrient it is lacking? In the hopes that I’m right, I just fed it a very small amount of 24(N), 8(P205), and 16(K20). Is this kind of plant food safe for a Ti plant, and how long will it take to notice any changes? Viriditas (talk) 20:56, 2 April 2022 (UTC)

April 3

Fossil fuel consumption to grow vegetable oil.

Following discussion (elsewhere): It's after reading this very sketchy article.

- The question is: We grow vegetable oil with the most efficient, modern, big scale and sustainable method.

- We convert this oil to jet fuel.

Did we get net gain of fossil fuel required for producing fertilizer + tending the crop? This is emission wise. Have captured CO2 from the air more than we added in the growing process?

-ZIMS — Preceding unsigned comment added by 77.124.34.8 (talk) 17:31, 3 April 2022 (UTC)

- The trend right now is going towards carbon-negative sustainable aviation fuel. It’s been all over the news for the last year. Viriditas (talk) 21:36, 3 April 2022 (UTC)

- You don't really have to produce a lot of fertiliser. In areas producing a lot of pigs, cows and chickens, there's so much manure that we don't know what to do with it, leading to huge pollution. At the same time, areas producing mostly plants use artificial fertiliser as it's cheaper than importing someone else's waste.

- The question comes down to: If we run all farming equipment on biofuels, can we produce net biofuel? Yes, we can. Actually, we did in 1800, when all farming equipment was powered by biofuel using horsepower. But to meet the energy requirements of modern aviation, we would need a lot of farmland. Probably more than is available.

- There's a lot of talk about making aviation sustainable, but there's hardly any progress; it's mostly for greenwashing the industry. We cannot produce enough biofuel, electric flying only makes sense for short hops in archipelagos (range is too short for long hops, whilst outside archipelagos land-based transport works better for the short hops), hydrogen requires so much storage volume that it isn't very practical for aviation (except in airships, but those aren't very practical themselves; using hydrogen in fixed-wing aircraft can't be ruled out completely though). There may be some possibilities with synthetic hydrocarbons (see Sabatier reaction), but that's not what most of the talk is about. Yet, to meet their fair share of the Paris Agreement, aviation has to be made sustainable within the next 15 years or so, or stopped altogether (I wouldn't mind). PiusImpavidus (talk) 09:29, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- I suppose airships, in particular hybrid airships, offer some hope for future sustainable aviation. --Lambiam 10:57, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Airships may have some niche applications, for surveillance, low-altitude cruises and oversized cargo delivery, but I doubt they will have much of a role in sustainable aviation. With a back-of-the-envelope calculation, a Hindenburg-class airship had about 100 times the frontal surface area of a Boeing 737 NG. The 737 suffers induced drag, doubling its drag, and flies faster, increasing drag 60–80 times, but also in thinner air, reducing drag by a factor 6 or so. Then the airship still has higher drag from its large size. This appears to be confirmed by engine size: the airship had 3.56MW of power, which at 135km/h translates to 95kN of thrust (a bit less if assuming non-ideal propellers). The 737 has about 27kN of maximum thrust at cruise altitude. And you can't gain much from flying slower in your airship, as minimum work for flying against a headwind is reached when your airspeed is 1.5 times the wind speed, so you need at least 80km/h cruising speed. So a Hindenburg-class airship needs more work to fly the same distance as a Boeing 737 NG, while carrying only half the payload. Environmentally, airships are pretty bad. Hybrid airships may be between classical airships and fixed-wing aircraft, but that makes them still worse than fixed-wing aircraft. PiusImpavidus (talk) 13:50, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- HAV said the CO2 footprint per passenger on its airship would be about 4.5kg, compared with about 53kg via jet plane... the hybrid-electric Airlander 10 could make the same [short-haul inter-city] connections with 10% of the carbon footprint from 2025, and with even smaller emissions in the future when the airships were expected to be all-electric powered. [7] Alansplodge (talk) 22:32, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Now I wonder what assumptions are behind that comparison. On very short distances, jet aircraft cannot reach their cruising altitude and speed, so they cannot exploit the high efficiency jet engines have at high speed. In that case, the propellers of the airship perform much better than the jet engines of a small jet, giving the jet much less of an advantage, or even a disadvantage. But on such short hops, airlines tend to use turboprops, which are far more efficient than jets at low speed and similar to the engines and props of an airship. Now compare that airship to an ATR 72. It actually has the same payload capacity and engine power as a Hindenburg-class airship, but is 4 times faster, using 75% less time and fuel to cover the same distance. Or even less than that, considering they only use full power during take-off. In fact, our article says that the ATR 72 uses just 21 grammes of fuel per seat-kilometre, but doesn't say at what distance. PiusImpavidus (talk) 10:04, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- HAV said the CO2 footprint per passenger on its airship would be about 4.5kg, compared with about 53kg via jet plane... the hybrid-electric Airlander 10 could make the same [short-haul inter-city] connections with 10% of the carbon footprint from 2025, and with even smaller emissions in the future when the airships were expected to be all-electric powered. [7] Alansplodge (talk) 22:32, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Airships may have some niche applications, for surveillance, low-altitude cruises and oversized cargo delivery, but I doubt they will have much of a role in sustainable aviation. With a back-of-the-envelope calculation, a Hindenburg-class airship had about 100 times the frontal surface area of a Boeing 737 NG. The 737 suffers induced drag, doubling its drag, and flies faster, increasing drag 60–80 times, but also in thinner air, reducing drag by a factor 6 or so. Then the airship still has higher drag from its large size. This appears to be confirmed by engine size: the airship had 3.56MW of power, which at 135km/h translates to 95kN of thrust (a bit less if assuming non-ideal propellers). The 737 has about 27kN of maximum thrust at cruise altitude. And you can't gain much from flying slower in your airship, as minimum work for flying against a headwind is reached when your airspeed is 1.5 times the wind speed, so you need at least 80km/h cruising speed. So a Hindenburg-class airship needs more work to fly the same distance as a Boeing 737 NG, while carrying only half the payload. Environmentally, airships are pretty bad. Hybrid airships may be between classical airships and fixed-wing aircraft, but that makes them still worse than fixed-wing aircraft. PiusImpavidus (talk) 13:50, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- I suppose airships, in particular hybrid airships, offer some hope for future sustainable aviation. --Lambiam 10:57, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Here's a glossy leaflet published by the RSB, who certify sustainable aviation fuel. On page 5, HEFA appears in a table, and it says the blending ratio (with fossil fuel kerosene) is "up to 50%". The CNN article attaches the optimistic word "currently" to that. On page 8, the leaflet says the RSB "Ensures that Sustainable Aviation Fuels produce at least 50% less GHG emissions than conventional jet kerosene", but the meaning of that isn't clear - for all we know this is just based on the false assumption that zero fossil fuel is required to produce the biofuel portion of the blend. To my mind the entire job and purpose of the RSB is to investigate the amount of fossil fuel used to produce biofuels, but perhaps they don't. There are a lot of words in the leaflet, but none of them seem to be about investigating that. This other document, Standard for advanced fuels, mentions "Greenhouse gas calculation", which is in this third document, RSB GHG Calculation Methodology (RSB-STD-01-003-01). Tracing exactly how the operators got their fuel certified is difficult: what assumptions were made? How much of it is "carbon offsetting"? Which things did they refrain from voluntarily investigating? Also, the cooking oil seems to be used oil recovered from restaurants and homes, so the assumption "it was going to be thrown away, therefore we don't have to assess how it was grown" might be in play. If there can be an economy where all aviation fuel is obtained from cooking waste, this changes the question into one about the production of cooking oil in general, separate from its use as aviation fuel. However, if cooking oil users are being subsidised by the aviation industry (paid for the waste oil), they will use more cooking oil, so there's still a question about whether the scheme adds up. Card Zero (talk) 14:52, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

April 4

Weighing less than nothing

In Don Rosa's comic The Universal Solvent, the Ducks travel to the centre of the Earth in a vertical shaft. At one point, they notice gravity has started working in the opposite direction - it pulls them up instead of down. According to the story, this is because the majority of the Earth's mass is now above the Ducks instead of below them. Assuming travelling so far down were possible in the first place, is this really what would happen? JIP | Talk 11:20, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Not really. At any point nearer to the top of the shaft than the centre of the Earth there would be more mass below. Think of the other hemisphere for a start. Only at the centre would gravity cease pulling down. Still, this is science fiction so interposing reality isn't always helpful! Martin of Sheffield (talk) 11:29, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Thanks for the answer. It kind of figures. The further down they go, the less they weigh - but their weight stays positive the whole time, as the other hemisphere is still below them. I wonder how Rosa, who has a Bachelor's Degree in civil engineering, failed to spot this. JIP | Talk 11:43, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Shell theorem says: "If the body is a spherically symmetric shell (i.e., a hollow ball), no net gravitational force is exerted by the shell on any object inside, regardless of the object's location within the shell." They would simply feel the gravity of the sphere closer to the centre while everything else would cancel out. I don't think the author actually thought the story was scientifically accurate. It's a Donald Duck story, not hard science fiction. PrimeHunter (talk) 11:56, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- It's actually quite a bit more complex than that once you factor in the changing density. See Gravity of Earth for the full, unexpurgated, gory details. Martin of Sheffield (talk) 12:05, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Unless they mean they've already passed the center of the Earth within the shaft and was on the "opposite" side already, where "up" instead of "down" is pointing toward the center. GeorgiaDC (talk) 18:44, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

The shell theorem applies to shells (such as a Dyson sphere). However, Earth is a ball. 78.1.172.11 (talk) 21:11, 4 April 2022 (UTC)- Edit: Nvm I've read PrimeHunter's comment again and I see we don't actually disagree. 78.1.172.11 (talk) 21:20, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Shell theorem says: "If the body is a spherically symmetric shell (i.e., a hollow ball), no net gravitational force is exerted by the shell on any object inside, regardless of the object's location within the shell." They would simply feel the gravity of the sphere closer to the centre while everything else would cancel out. I don't think the author actually thought the story was scientifically accurate. It's a Donald Duck story, not hard science fiction. PrimeHunter (talk) 11:56, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Thanks for the answer. It kind of figures. The further down they go, the less they weigh - but their weight stays positive the whole time, as the other hemisphere is still below them. I wonder how Rosa, who has a Bachelor's Degree in civil engineering, failed to spot this. JIP | Talk 11:43, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Assuming a spherically symmetrical, solid

cowEarth, if you dug a giant whole through the dead center of the earth, and out of the other side, and then jumped in the hole, ignoring air-friction, you would be a harmonic oscillator, barely reaching the other side (your center of mass would clear the surface of the other side of the earth to the exact height your center of mass currently is on this side of the other), bouncing from one side to the other. This video from Science Asylum does a good job explaining the physics of the situation. --Jayron32 12:28, 4 April 2022 (UTC)- If you instantly teleported out a hole and turned real physics back on what would happen? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 14:47, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- If you returned air resistance into the picture, you would behave like a dampened harmonic oscillator, gradually slowing down and your return points would get further and further from either hole, until you came to a gentle rest floating at the exact center of the earth. --Jayron32 15:12, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Also, if you returned the Earth's actual gravitational irregularities, I doubt you'd ever make it to the center in one piece. You're going to be moving at terminal velocity pretty quickly, and given the irregularities in gravity on your long trip, you'll probably be pinging off the sides of your shaft rather violently. And, since part of the Earth are molten (liquid) rock and metal, your hole would very quickly fill in, and then exposed to the air above it, would cool down pretty quickly. You wouldn't make it past the Asthenosphere, which means you only would fall for a few kilometers before smacking into hot, partially solidified magma. --Jayron32 16:33, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Also, also, as I look at some information in Kola Superdeep Borehole, even within the crust, when you get down past about 10 km, the temperature is hot enough to boil water. You'd probably bake to death before you even hit the bottom. --Jayron32 16:36, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Also, also, also, consider that Caisson disease, aka "the Bends", is a real possibility at depths of that level, given the massive increase in air pressure you are likely to experience. --Jayron32 16:52, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Also, also, as I look at some information in Kola Superdeep Borehole, even within the crust, when you get down past about 10 km, the temperature is hot enough to boil water. You'd probably bake to death before you even hit the bottom. --Jayron32 16:36, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Also, if you returned the Earth's actual gravitational irregularities, I doubt you'd ever make it to the center in one piece. You're going to be moving at terminal velocity pretty quickly, and given the irregularities in gravity on your long trip, you'll probably be pinging off the sides of your shaft rather violently. And, since part of the Earth are molten (liquid) rock and metal, your hole would very quickly fill in, and then exposed to the air above it, would cool down pretty quickly. You wouldn't make it past the Asthenosphere, which means you only would fall for a few kilometers before smacking into hot, partially solidified magma. --Jayron32 16:33, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- If you returned air resistance into the picture, you would behave like a dampened harmonic oscillator, gradually slowing down and your return points would get further and further from either hole, until you came to a gentle rest floating at the exact center of the earth. --Jayron32 15:12, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- If you instantly teleported out a hole and turned real physics back on what would happen? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 14:47, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- a decompression accident would be a problem on the way back up, oxygen toxicity due to its high partial pressure would get you on the way down.

- I always thought that (assuming you didn't fill most of it with air compressed to specific gravities >>1) some spectacular implosion at at least c. the speed of sound of each Earth layer would happen, as most of the cylinder surface would have pressure of 1 to 3.6 million atmospheres. How much magma gas would come out of solution from this brief exposure to the hole's lower pressure, and how dramatic of an eruption that could cause I don't know. Would magma not reach the entrance because mantle is denser than continental crust or would it barely leak out or spurt 100 meters high or something stronger and less Hawaiian? How big or small would the earthquake be? How far from the hole would crack? And if it's wide enough for bouncing off the edge to not come first then how far could you fall before things get bad? Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 23:32, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Even worse than gravitational irregularities is the Coriolis force sending you off cource. Unless you travel exactly Pole to Pole. PiusImpavidus (talk) 10:15, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- The comic seems to say that their weight is decreasing (again because of the shell theorem) and that they will soon be weightless (at the center of the Earth), not that gravity is pulling them in the opposite direction. --Amble (talk) 19:18, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Did the comic literally say they weigh "less than nothing"? --←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 22:19, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

Nitrogen triiodide; is the purple cloud toxic?

I asked this question at Talk:Nitrogen triiodide#Toxicity?, but I thought that it was worth reposting here.

Youtube is full of videos showing Nitrogen triiodide exploding with a purple cloud. Our article on Nitrogen triiodide should say whether that purple cloud is toxic.

The first paragraph of the article says "...releasing a purple cloud of iodine vapor", but later the article says

"The dry material is a contact explosive, decomposing approximately as follows:

8 NI3 · NH3 → 5 N2 + 6 NH4I + 9 I2"

So which is it? "Iodine vapor"? Or is the purple cloud a combination of Ammonia, Ammonium iodide, and Elemental Iodine (I2)? And is the purple cloud an actual vapor or is it a cloud of solid (liquid?) Iodine particles? Iodine boils at 113.7 °C and Ammonium iodide boils at 551 °C so (based upon my extensive education (which consists of getting a C- in high-school chemistry)) it seems that only the Ammonia would be a vapor, while the purple stuff would be an aerosol.

Could someone who understands chemistry please write up a paragraph for that article with citations explaining what is in that purple cloud and whether it is toxic? 2600:1700:D0A0:21B0:5A9:3B45:A28C:DE50 (talk) 18:54, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Iodine is a solid under standard conditions, but it sublimes under these conditions to produce some violet iodine vapour - see Iodine#Properties. Mikenorton (talk) 22:01, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Ammonia is a colourless gas. I could find no mention of the colour of gaseous ammonium iodide, which suggests it is not remarkable. So the markedly violet colour of the cloud is rather likely purely due to the presence of iodine in the gas state. --Lambiam 22:54, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- The pictures at [8] look a lot more like a smoke or a dust than a gas to me. Could it be mostly a fine powder of iodine crystals? Of course the crystals create the gas, so there would have to be be gas as well. Either way, could it be that all the article needs is a "for more information see Iodine#Toxicity" link? 2600:1700:D0A0:21B0:5A9:3B45:A28C:DE50 (talk) 02:03, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- If you watch the video, you can see that the cloud looks like vapour more than dust once it starts to disperse. --Lambiam 09:35, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- The pictures at [8] look a lot more like a smoke or a dust than a gas to me. Could it be mostly a fine powder of iodine crystals? Of course the crystals create the gas, so there would have to be be gas as well. Either way, could it be that all the article needs is a "for more information see Iodine#Toxicity" link? 2600:1700:D0A0:21B0:5A9:3B45:A28C:DE50 (talk) 02:03, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- Ammonia is a colourless gas. I could find no mention of the colour of gaseous ammonium iodide, which suggests it is not remarkable. So the markedly violet colour of the cloud is rather likely purely due to the presence of iodine in the gas state. --Lambiam 22:54, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- What do we do when we see a chemical explosion and a cloud and we're not sure how hazardous it is?

- Well, it turns out that this is very common!

- I pull out my handy paper copy of the Department of Transportation Emergency Response Guidebook (2020 edition, available for free in PDF format and probably available for free at your local US fire department!)

- This is a guidebook for first responders "during the initial phase of a transportation incident involving hazardous materials/dangerous goods". How often do we find a weird chemical with unknown safety parameters? Too often.

- Page 1 of the book is the decision-making flow-chart. Follow along - the flow chart will direct you to Guide 111: "Unidentified Cargo" - and lists all the potential hazards. "Evacuation: Immediate precautionary measure - Isolate spill or leak area for at least 100 meters (330 feet) in all directions."

- If you say the dry material is a "contact explosive": That'd be ... Guide 112 - "EVACUATION - Immediate precautionary measure. Isolate spill or leak area immediately for at least 500 meters (1/3 mile) in all directions. MAY EXPLODE AND THROW FRAGMENTS 1600 METERS (1 MILE) OR MORE IF FIRE REACHES CARGO."

- Later when we have time for it, we can pull out the MSDS and figure out how to comply with the necessary local and national chemical handling guidelines. In the short term, don't play with chemicals if you aren't trained to deal with them and their hazards.

- Meanwhile - if you think people who are skilled and trained in chemistry have the time to micro-analyze the safety concerns of every possible type of chemical they might encounter, and evaluate whether this particular purple cloud matches that particular textbook example, and then clearly cite the details on a free encyclopedia, you are grossly misinformed. Don't mess around with chemicals, don't mess around with explosives, and if you're not sure if it's hazardous, assume it is hazardous and don't mess around with it.

- Nimur (talk) 23:18, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Got it. You have chosen to criticize someone for daring to ask that a Wikipedia article on Nitrogen triiodide not give the reader two different answers for what it turns into when it explodes.

- And we shouldn't have information such as Iodine#Toxicity, Phosphorus#Precautions, Organic mercury#Toxicity and safety, Thermite#Hazards, or any of the other thousands of places where Wikipedia talks about the hazards of a substance. Got it.

- Please go away. Your answer was not helpful. 2600:1700:D0A0:21B0:5A9:3B45:A28C:DE50 (talk) 02:03, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- Telling an editor with over 16 years experience here to "go away" is not likely to get you anywhere. --←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:59, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

[9] says: "Although it is possible to make pure nitrogen triiodide (which is a red solid) by reacting boron nitride with iodine fluoride, the substance that is actually produced by the reaction I used to perform is more complex. It is an adduct of nitrogen triiodide and ammonia. An adduct is a not-quite compound. The two molecules, nitrogen triiodine and ammonia, are attracted to each other to form a new molecule that is represented by the usual NI3 and NH3 with a dot in between. Initially on formation there are five ammonias to each nitrogen triiodide, but as the substance dries it gives off ammonia to end up with a one to one adduct. What has formed in the solid are chains of nitrogen triiodide with ammonia molecules linking them."

I found the idea of an Adduct interesting. Is this worth covering in the article? 2600:1700:D0A0:21B0:5A9:3B45:A28C:DE50 (talk) 02:03, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- It's just iodine, from personal experience making the stuff without it being held in ammonia. Abductive (reasoning) 09:36, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

- The ammonia and iodine gases that are released are toxic. The ammonia air level reported to be considered immediately dangerous to life or health is 300 ppm.[10] The iodine air level reported to be considered immediately dangerous to life or health is 2 ppm.[11][12] --Lambiam 10:01, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

Special relativity : 3.4 Relativity without the second postulate

With only the principle of relativity [1], what about the CERN collider [2] in which proton beams traveling in opposite directions collide at 99.9999991% of c? If you consider each beam as a frame of reference, for each, the other arrives at a speed close to 2c. And in case each beam is 50% of c you get a Lorentz factor = 1/0, so you can't apply the Lorentz transformation, only the Galilean transformation, right? In fact Einstein's relativity and the Lorentz transformation apply only to electromagnetic rays, not to inertial objects themselves with not invariant speed , but only to the reflection of electromagnetic rays on inertial objects! Didn't Einstein confuse what we see with what is? Malypaet (talk) 23:21, 4 April 2022 (UTC)

- Hasn't the constancy of the speed of light been consistently experimentally confirmed? --Lambiam 09:25, 5 April 2022 (UTC)

References