Lachin: Difference between revisions

AntonSamuel (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Maidyouneed (talk | contribs) →2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war: Source refers to statement by Aliyev |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

Following the ceasefire, only around 200 Armenians remained in the [[Lachin corridor]], with 100-120 of them being in Lachin.<ref name=hetq /> |

Following the ceasefire, only around 200 Armenians remained in the [[Lachin corridor]], with 100-120 of them being in Lachin.<ref name=hetq /> |

||

According to the president of Azerbaijan [[Ilham Aliyev |

According to the president of Azerbaijan [[Ilham Aliyev]], a new corridor will be built in the region as the Lachin corridor passes through the city of Lachin, and when this corridor is ready, the city will be returned to the Azerbaijani administration.<ref>{{Cite web|date=1 December 2020|title=İlham Əliyev: "Yeni dəhliz hazır olandan sonra Laçın şəhəri bizə qaytarılacaq"|url=https://www.bbc.com/azeri/live/azerbaijan-54577122?ns_mchannel=social&ns_source=twitter&ns_campaign=bbc_live&ns_linkname=5fc6011f65be0302b81c5196%26%C4%B0lham%20%C6%8Fliyev%3A%20%22Yeni%20d%C9%99hliz%20haz%C4%B1r%20olandan%20sonra%20La%C3%A7%C4%B1n%20%C5%9F%C9%99h%C9%99ri%20biz%C9%99%20qaytar%C4%B1lacaq%22%262020-12-01T08%3A41%3A47.987Z&ns_fee=0&pinned_post_locator=urn:asset:2b98175b-1f04-466c-b371-e8b43196ccbb&pinned_post_asset_id=5fc6011f65be0302b81c5196&pinned_post_type=share|access-date=4 December 2020|work=BBC Azerbaijani Service|language=az}}</ref> |

||

== Geography == |

== Geography == |

||

Revision as of 15:48, 1 May 2022

Lachin / Berdzor

Laçın / Բերձոր | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: Template:Xb_type:city(100-120) 39°38′27″N 46°32′49″E / 39.64083°N 46.54694°E | |

| Country (de facto; civil) | |

| • Province | Kashatagh |

| Country (de jure) | |

| • District | Lachin |

| Military control | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Narek Alexanyan[1] (de facto) Agil Nazarli[2] (de jure) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

| • Total | 100−120 |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (UTC) |

Lachin (Azerbaijani: Laçın, , lit. 'falcon'; Kurdish: Laçîn; Armenian: Լաչին) or Berdzor (Armenian: Բերձոր) is a town within the strategic Lachin corridor, which links the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.[4]: 8, 10, 31 It is under the supervision of the Russian peacekeeping force following the ceasefire agreement that ended the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. The town came under the de facto control of the breakaway Republic of Artsakh after 1992, administrated as part of its Kashatagh Province, and is the de jure centre of the Lachin District of Azerbaijan.[5]

History

Early history

Cuneiform inscriptions dating back to the Urartian period have been found in the caves surrounding the town.[6] The area was first mentioned by Armenian sources as Berdadzor (Armenian: Բերդաձոր), a canton of the historic Artsakh province of Greater Armenia;[7][8] it was alternatively transcribed as Beradzor, Berdzor, or Berdzork.[9] The reputed author Movses Kaghankatvatsi mentions a so-called Berdzor horse purportedly indigenous to the region, as does Makar Barkhudaryan, an Apostolic bishop, traveler, polymath, and ethnographer from Shushi.[10] During the medieval period, the town Berdzor was mentioned as being a part of the Artsakh province within the domain of the Armenian Bagratid Kingdom.[11]

Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu's private secretary Shihab ad-Din an-Nasawi referred to the settlement as both Berdadzor and a new name, Kaladara.[12]

Berdzor had its own local Meliks during the 15th-17th centuries and fell under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Melikdom of Kashatagh.[13] The Armenian settlement of Berdzor was eventually abandoned. Following the displacement of the Armenian population, the area was then repopulated with Kurdish tribes.[14] The modern settlement was built using the stones from the ancient Armenian settlement.[15]

The town was formerly also known as Abdallar, named after the Turkic Abdal tribe.[16][17][18] In 1914, Abdallar was a small relatively insignificant village of about 124 Turkic-speaking Kurds.[19] It was granted town status in 1923 and then renamed Lachin (a Turkic first name meaning falcon) in 1926.[20][16]

In the early 1920s, Vladimir Lenin's letter to Nariman Narimanov "had implied that Lachin was to be included in Azerbaijan, but the authorities in Baku and Yerevan were given promises that were inevitably contradictory."[21]

Red Kurdistan

On 7 July 1923, the town of Lachin became the administrative centre of Kurdistansky Uyezd of the Azerbaijan SSR, often known as Red Kurdistan.[22] It was dissolved on 8 April 1929: Kurdish schools and newspapers were closed.[23]

On 30 May 1930, the Kurdistan Okrug replaced the uyezd. It included the territory of the former Kurdistansky Uyezd, as well as Zangilansky District and a part of Dzhebrailsky District. The okrug, like the uyezd before it, was founded to appeal to Kurds beyond Soviet borders in Iran and Turkey, but the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs would ultimately protest this policy due to its negative effect on relations with Turkey and Iran. Due to these concerns, the okrug was abolished less than a month after its foundation, on 23 July 1930.[24]

In the late 1930s, Soviet authorities deported most of the local Kurdish population as well as much of the Kurds elsewhere in Azerbaijan and Armenia to Kazakhstan.[25]

To its Kurdish population, the city was known as Laçîn.[26][27]

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

First Nagorno-Karabakh War

The town and hinterland of Lachin was the location of severe fighting during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1990–1994).[citation needed]

During May 1992, an Armenian offensive captured the town; as a result, Lachin became a strategic link between Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh region -the Lachin corridor.[4]: 8, 10, 31 The disfigured bodies of Armenian civilians killed by Azerbaijani soldiers in 1992 were discovered near Lachin on May 28, 1993. The civilians had attempted to flee Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia and were reportedly massacred by the Gray Wolves.[28]

Following the town's capture by Armenian forces, it was looted and burned.[29] The mainly Azerbaijani population fled and became internally displaced people. British reporters witnessed looting and burning in Lachin, with trucks and cars piled high with looted furniture and household utensils moving to Armenia, and big convoys blocking the road. Looters took everything of value, including livestock, before setting houses on fire. An Armenian sergeant said to the British journalists that the looting was done because the Azerbaijanis had previously pillaged 23 villages. Among the Armenian looters there also were civilians from Stepanakert, which had been shelled by the Azerbaijanis for eight months and had been without light and water for several weeks.[29][30] A Canadian journalist who visited the town a few months later noted that "the destruction is absolute. No building, no home, no school, not a bus shelter has been left unscarred".[31]

From 1992, Lachin was administrated by the Republic of Artsakh as part of its Kashatagh Province. Artsakh repopulated the city by attracting ethnic Armenians from Armenia and Lebanon.[5] According to journalist Onnik Krikorian, although the official statistics claimed that the number of Armenian residents in Lachin was 2200, the actual figure was around fifty per cent less. While some settlers were refugees from Azerbaijan and Karabakh, as well as from the diaspora, Krikorian wrote that most were poor families from Armenia, attracted by the promise of land, livestock and social benefits that averaged 4,000 Armenian drams (about ten US dollars) per child. Krikorian also wrote that the Armenian population was leaving the region due to decreased government funding and the uncertainty of region's status.[32]

The OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs had noted that "Lachin has been treated as a separate case in previous negotiations." The Lachin corridor and the Kalbajar district had been at the centre of Armenian demands during the Nagorno-Karabakh peace talks with Azerbaijan.[33]

On 16 June 2015 European Court of Human Rights passed a judgement in the case of "Chiragov and Others v. Armenia", which concerned the complaints by six Azerbaijani ethnically-Kurdish refugees that they were unable to return to their homes and property in the district of Lachin, in Azerbaijan, from where they had been forced to flee in 1992 during the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. The Court confirmed that Armenia exercised effective control over Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding territories and thus had de facto jurisdiction over the district of Lachin. The Court also found that the denial by the Armenian government of access to the applicants’ homes constituted an unjustified interference with their right to respect for their private and family lives as well as their homes.[34]

2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war

Following the ceasefire agreement that ended the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, the Lachin District was returned to Azerbaijan on 1 December.[35] Today, Russian peacekeepers continue to secure safe passage through the Lachin corridor.[36] However, the unclear and unstable situation in the region have caused many Armenians to evacuate from the city.[5][37]

The Artsakh mayor of Lachin, Narek Aleksanyan, first called on the ethnic Armenian population of the town to evacuate. However, later Aleksanyan stated that the agreement had been changed and that Lachin, Sus, and Zabukh (Aghavno) which are located inside the Lachin corridor would not be handed over to Azerbaijan, urging the Armenian population to stay in their homes. Despite Aleksanyan's calls, the vast majority of Armenians in Lachin, as well as Lebanese-Armenians in Zabukh (Aghavno) fled the region.[38][1] Azerbaijani MP Zahid Oruj, the chairman of the Center for Social Research, which is linked to the Azerbaijani government, denied that the Lachin District would not be handed over in its entirety.[38]

On December 1, Azerbaijani forces, with tanks and a column of trucks, entered the district,[39] and the Azerbaijani MoD released footage from the Lachin district.[40] On December 3, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence released video footage from the town of Lachin.[41]

Following the ceasefire, only around 200 Armenians remained in the Lachin corridor, with 100-120 of them being in Lachin.[3]

According to the president of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev, a new corridor will be built in the region as the Lachin corridor passes through the city of Lachin, and when this corridor is ready, the city will be returned to the Azerbaijani administration.[42]

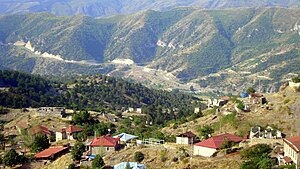

Geography

The town is scenically built on the side of a mountain on the left bank of the river Hakari.[43]

Economy and culture

As of 2015, the population is mainly engaged in different state institutions. The town has a municipal building, a regional hospital, four dental clinics, two secondary schools, the Berdzor Music School and the Berdzor Art and Sports School, and a kindergarten.[44]

Demographics

| Year | Population | Ethnic groups | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1907 | 145 | Mostly Tatars (later known as Azerbaijanis) | Caucasian Calendar[45] |

| 1914 | 124 | Mostly Tatars | Caucasian Calendar[19] |

| 1926 | 435 | 37.7% Turks (Azerbaijanis), 25.3% Kurds, 15.2% Armenians, 13.1% Russians | Soviet census[46][unreliable source?] |

| 1939 | 1,063 | 80.7% Azerbaijani, 11.6% Armenians, 6.4% Russians | Soviet census[47][unreliable source?] |

| 1959 | 2,329 | 94.5% Azerbaijani, 4.3% Armenians 1% Russians | Soviet census[48][unreliable source?] |

| 1970 | 4,990 | 95% Azerbaijani, 2.7% Russians & Ukrainians, 1.1% Armenians | Soviet census[49][unreliable source?] |

| 1979 | 6,073 | 99.1% Azerbaijani | Soviet census[50][unreliable source?] |

| 1989 | 7,829 | Soviet census[51] | |

| 2005 | 2,190 | ~100% Armenians | NKR census[52] |

| 2015 | 1,900 | ~100% Armenians | NKR estimate[53] |

| 2021 | 100-120 | ~100% Armenians |

Twin cities

Lachin is twinned with:

Gallery

-

View of the town

-

Former WW2 memorial turned into Nagorno-Karabakh conflict memorial

-

Playground in the town

-

View of part of Lachin

-

Road in Lachin

-

Building of Armenian mobile operator company

-

Holy Ascension Church in Berdzor, opened in 1998

References

Notes

- ^ a b Van Novikov (December 1, 2020). Stepan Kocharyan (ed.). "Berdzor mayor presents details amid vague situation". armenpress.am. Armenpress. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "İcra hakimiyyətinin başçısı". lachin-ih.gov.az. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Sara Petrosyan (February 22, 2021). "Փոքրաթիվ հայեր դեռևս բնակվում են Քաշաթաղում, բայց դա ռուսների քմահաճույքով է պայմանավորված". hetq.am. Hetq. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ a b The international politics of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict : the original "frozen conflict" and European security. Svante E. Cornell. New York, NY. 2017. ISBN 978-1-137-60006-6. OCLC 971245887.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Vendik, Yuri (November 17, 2020). "Армяне оставляют Лачин, несмотря на конец войны в Карабахе и прибытие российских миротворцев". BBC Russian Service (in Russian). Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ A.E. Movsisyan (2016). "Damaged Cuneiform Inscription of Berdzor Cave". Спелеология и спелестология (in Russian) (7). Yerevan State University: 248–249.

- ^ Hewsen. Armenia, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Մեծ Հայքի վարչական բաժանումը

- ^ The Dictionary of the toponyms of Armenia and the adjacent regions, Volume 3, Yerevan State University, YSU Publishing House, Yerevan, 1988, p. 665.

- ^ Barkhudaryan, Makar (1895). Aghuanitsʻ erkir ew dratsʻikʻ ; Artsʻakh. Baku: Gandzasar Astuatsabanakan Kentron. ISBN 99930-70-01-7. OCLC 44548270.

- ^ Minorsky, Vladimir (1953). "Caucasica IV" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 15 (3). London: Cambridge University Press: 504–529. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00111462. JSTOR 608652.

- ^ Шихаб ад-дин ан-Насави. Сират ас-султан Джалал ад-Дин Манкбурны (ЖИЗНЕОПИСАНИЕ СУЛТАНА ДЖАЛАЛ АД-ДИНА МАНКБУРНЫ), М. 1996, стр. 270

- ^ Карагезян А. К локализации гавара Кашатаг // Вестн. обществ. наук АН АрмССР. 1987. № 1. С. 44—45.

- ^ Шнирельман В.А. Войны памяти: мифы, идентичность и политика в Закавказье. — ИКЦ «Академкнига», 2002. — С. 199. — ISBN 5-94628-118-6

- ^ Karapetyan, Samvel (2001). "Berdzor (Lachin)". Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh (PDF). "Gitutiun" Publishing House of NAS RA. p. 169. ISBN 5-8080-0468-3.

- ^ a b Pospelov, p. 23

- ^ Karapetian, Samvel. Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabagh. Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Map of Armenia and Adjacent Countries by H. F. B. Lynch and F. Oswald in Armenia, Travels and Studies. London: Longmans, 1901.

- ^ a b “The Caucasian Calendar for 1915” Tblisi: 1914, p.82 (in Russian)

- ^ "ЛАЧИН". dic.academic.ru.

- ^ Alexandre Bennigsen and S. Enders Wimbush. Muslims of the Soviet Empire. C. Hurst & Co Publishers, 1986, pp. 202, 286. ISBN 1-85065-009-8.

- ^ McDowall, David. A Modern History of the Kurds, 3rd. ed. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004, p. 492.

- ^ Catherine Cosman, "Soviet Kurds Face Loss of Their Identity," New York Times, May 13, 1991/June 2, 1991.

- ^ (in Russian) Партизаны на поводке.

- ^ (in Russian) Russia and the problem of Kurds Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leezenberg, Michiel (2014). Soviet Orientalism and Subaltern Linguistics: The Rise and Fall of Marr's Japhetic Theory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 107.

- ^ "DAĞLIK KARABAĞ – Kürt'ün evine turist olarak bile gidemediği yer..." www.rudaw.net. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nagorno Karabakh". HRW.

- ^ a b Steele, Jonathan (May 25, 1992). "Eyewitness: Armenia's looters follow its troops into Azerbaijan - Tit-for-tat pillage of deserted Lachin succeeds a war that may not yet be over". The Guardian.

- ^ Seely, Robert (May 25, 1992). "Armenian looters burn down village". The Times. p. 8.

- ^ Brock, Daniel (August 30, 1993). "Europe's forgotten war". Maclean's. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Krikorian, Onnik (September 29, 2006). "Lachin: The Emptying Lands". IWPR. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ CountryWatch - Interesting Facts Of The World Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Press release issued by the Registrar of the Court. "Azerbaijani refugees' rights violated by lack of access to their property located in district controlled by Armenia". European Court of Human Rights. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ "Азербайджан взял под контроль Лачин спустя 28 лет". Caucasian Knot (in Russian). December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Rusiya Müdafiə Nazirliyi: Laçın dəhlizində hərəkətə sülhməramlılar nəzarət edir". BBC Azerbaijani Service (in Azerbaijani). December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijani troops enter Lachin district in Nagorno-Karabakh". TASS. November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Laçın şəhəri ermənilərdəmi qalır? Ermənilərə belə deyilib, amma onlar şəhəri tərk edir". BBC Azerbaijani Service (in Azerbaijani). November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijani Forces Enter Third District Under Nagorno-Karabakh Truce". RFERL.org. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Azərbaycan Müdafiə Nazirliyi Laçında dövlət bayrağının asılması barədə video yayıb". BBC Azerbaijani Service (in Azerbaijani). December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Laçın şəhərinin videogörüntüləri". Facebook.

- ^ "İlham Əliyev: "Yeni dəhliz hazır olandan sonra Laçın şəhəri bizə qaytarılacaq"". BBC Azerbaijani Service (in Azerbaijani). December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Лачин, Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ Hakob Ghahramanyan. "Directory of socio-economic characteristics of NKR administrative-territorial units (2015)".

- ^ Кавказский календарь .... на 1910 год (in Russian). Tiflis: Office of the Viceroy of the Caucasus. 1910. p. 170.

- ^ "Курдистанский уезд 1926". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru.

- ^ "Лачинский район 1939". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru.

- ^ "Лачинский район 1959". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru.

- ^ "Лачинский район 1970". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru.

- ^ "Лачинский район 1979". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". demoscope.ru.

- ^ http://census.stat-nkr.am/nkr/1-1.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Urban communities of the NKR" (PDF). stat-nkr.am. National Statistical Service of Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. January 1, 2015. p. 13.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Protests California Town’s Recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh." RIA Novosti. December 6, 2013.

Bibliography

- Е. М. Поспелов (Ye. M. Pospelov). "Имена городов: вчера и сегодня (1917–1992). Топонимический словарь." (City Names: Yesterday and Today (1917–1992). Toponymic Dictionary." Москва, "Русские словари", 1993.

External links

- Pictures of Lachin

- Onnik Krikorian, Armenia’s Strategic Lachin Corridor Confronts a Demographic Crisis, eurasianet.org, Sep 15, 2006.

- More information about Lachin from Armeniapedia.com

- "Lachin". Azerb.com. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- "History of Artsakh (Part 3)". Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- Lachin (as Laçın) at GEOnet Names Server