Barbary pirates: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

[[Category:Barbary pirates]] |

[[Category:Barbary pirates]] |

||

[[de: |

[[de:Barbareskenstaat]] |

||

[[es:Pirata berberisco]] |

[[es:Pirata berberisco]] |

||

[[fr:Barbaresque]] |

[[fr:Barbaresque]] |

||

Revision as of 16:36, 15 March 2008

The Barbary pirates, also sometimes called Ottoman corsairs, were pirates and privateers that operated from north Africa (the "Barbary coast"). They operated out of Tunis, Tripoli, Algiers, Salé and ports in Morocco, preying on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea from the time of the Crusades until the early 19th century. Their stronghold was along the stretch of northern Africa known as the Barbary Coast (a medieval term for the Maghreb after its Berber inhabitants), although their predation was said to extend throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard, and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland. As well as preying on shipping, raids called Razzias were often made on European coastal towns for capturing Christian slaves, who were sold in slave markets in places such as Algeria and Morocco.[1][2] According to Robert Davis between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by pirates and sold as slaves between the 16th and 19th century. These slaves were captured mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain and Portugal, and from more distant places like France or England, the Netherlands, Ireland and even Iceland and North America.

The impact of these attacks were devastating – France, England, and Spain each lost thousands of ships, and long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants. Pirate raids discouraged settlement along the coast until the 19th century.

In 1544, Khair ad Din captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners in the process, and deported to slavery some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[3] In 1551, Turgut Reis (known as Dragut in the West) enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Libya. When pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy in 1554 they took an estimated 7,000 slaves.[4] In 1555, Turgut Reis sailed to Corsica and ransacked Bastia, taking 6000 prisoners. In 1558 Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and carried off 3,000 survivors to Istanbul as slaves.[5] In 1563 Turgut Reis landed on the shores of the province of Granada, Spain, and captured coastal settlements in the area, such as Almuñécar, along with 4,000 prisoners. Barbary pirates frequently attacked the Balearic islands, resulting in many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches being erected. The threat was so severe that island of Formentera became uninhabited.[6][7]

Between 1609 and 1616 England alone had 466 merchant ships lost to Barbary pirates.[8] Slave-taking persisted into the 19th century when Barbary pirates would capture ships and enslave the crew. Even the United States was not immune. For example, one American slave reported that 130 other American seamen had been enslaved by the Algerians in the Mediterranean and Atlantic just between 1785 and 1793. Isolated cases of piracy occurred on the Rif coast of Morocco even at the beginning of the 20th century, but the pirate communities which lived by plunder and could live by no other resource, vanished with the French conquest of Algiers in 1830.[9]

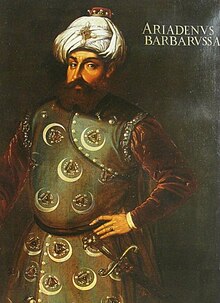

The most famous corsairs were the Ottoman Barbarossa (meaning Redbeard) brothers, Hızır (Hayreddin) and his older brother Oruç who took control of Algiers in the early 16th century and turned it into the center of Mediterranean piracy and privateering for the next three centuries, as well as establishing the Ottoman Empire presence in North Africa which lasted four centuries. Other famous Ottoman privateer-admirals included Turgut Reis (known as Dragut in the West), Kurtoğlu (known as Curtogoli in the West), Kemal Reis, Salih Reis and Koca Murat Reis.

History

Although piracy had existed in the region throughout the decline of the Roman Empire, the barbarian invasions, the Golden Age of Piracy and the Middle Ages, piracy became particularly flagrant in the 14th century with the decline of European naval power in relation to the Islamic powers, particularly the Ottomans. The town of Bougie was then the most notorious pirate base.

Following the conquest of Granada by Spain and the expulsion of the Moors in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, many Muslims from Spain emigrated to the coastal cities of North Africa. Under the tutelage of first the Islamic Mamelukes of Egypt and later the Muslim Ottomans, they, together with local Arab and Berber tribes, mounted expeditions called Razzias, Ital. from Ar. ghazwa to disrupt Christian sovereigns and capture the coveted white European women for the brothels of the East[10]. Under the power of the Ottomans in the 16th century, who organized the privateers, the Barbary pirates became most powerful in the 17th century, until declining in the face of European power throughout the 18th century until finally extinguished about 1830, when the French conquered Algiers and firmly put an end to the Barbary pirates and established French Algiers.

Several events influenced the growth of the pirates. The conquest of Granada by the Catholic sovereigns of Spain in 1492 drove many Moors into exile. They revenged themselves by piratical attacks on the Spanish coast. They had the help of Muslim adventurers from the Levant, of whom the most successful were Hızır and Oruç, natives of Mitylene. Spain in self-defense began to conquer the coast towns of Oran, Algiers and Tunis. Oruç having fallen in battle with the Spaniards in 1518, his brother Hızır appealed to Selim I, the Ottoman Sultan, who sent his troops. He drove the Spaniards in 1529 from the rocky island in front of Algiers, where they had a fort, and was the founder of the Ottoman power. From about 1518 till the death of Uluch Ali in 1587, Algiers was the main seat of government of the beylerbeys of northern Africa, who ruled over Tripoli, Tunisia and Algeria. From 1587 till 1659, they were ruled by Ottoman pashas, sent from Constantinople to govern for three years; but in the latter year a military revolt in Algiers reduced the pashas to nonentities. From 1659 onwards, these African cities, although nominally forming part of the Ottoman empire, were in fact anarchical military republics which chose their own rulers and lived by plunder.

During the first period (1518-1587), the beylerbeys were admirals of the sultan, commanding great fleets and conducting serious operations of war for political ends. They were slave-hunters and their methods were ferocious. After 1587, plunder became the sole object of their successors—plunder of the native tribes on land and of all who went upon the sea. The maritime side of this long-lived brigandage was conducted by the captains, or reises, who formed a class or even a corporation. Cruisers were fitted out by capitalists and commanded by the reises. Ten percent of the value of the prizes was paid to the treasury of the pasha or his successors, who bore the titles of agha or dey or bey.[11]

Era of the pirates

The first half of the 17th century may be described as the flowering time of the Barbary pirates. More than 20,000 captives were said to be imprisoned in Algiers alone. The rich were allowed to redeem themselves, but the poor were condemned to slavery. Their masters would on occasion allow them to secure freedom by professing Islam. A long list might be given of people of good social position, not only Italians or Spaniards, but German or English travellers in the south, who were captives for a time.[11]

In Iceland Murat Reis (Jan Janszoon) is said to have taken 400 prisoners, later raided the nearby island of Vestmannaeyjar. Among those captured in Vestmannaeyjar was Ólafur Egilsson, who was released with a ransom the next year and, upon returning back to Iceland, wrote a detailed book in 1628 about his experience. The sack of Vestmannaeyjar is known in The History of Iceland as Tyrkjaránið (The Turkish abductions) and is arguably the most horrible event in the history of Vestmannaeyjar[12].

In June 1631 Murat Reis, with pirates from Algiers and armed troops of the Ottoman Empire, stormed ashore at the little harbour village of Baltimore, County Cork. They captured almost all the villagers and bore them away to a life of slavery in North Africa.[11] The prisoners were destined for a variety of fates -- some would live out their days chained to the oars as galley slaves, while others would spend long years in the scented seclusion of the harem or within the walls of the Sultan's palace. The old city of Algiers, with its narrow streets, intense heat and lively trade, was a melting pot where the villagers would join slaves and freemen of many nationalities. Only two of them ever saw Ireland again. A detailed account of the sack of Baltimore, County Cork can be found in the book The Stolen Village: Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates by Des Ekin.

Although Barbary pirate attacks were more common in southern Portugal, south and east Spain, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Corsica, Elba, the Italian Peninsula (especially the coasts of Liguria, Toscana, Lazio, Campania, Calabria and Puglia), Sicily and Malta, they also attacked the Atlantic northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula. In 1617, the African corsairs launched their major attack in the region when they destroyed and sacked Bouzas, Cangas and the churches of Moaña and Darbo.

The chief sufferers were the inhabitants of the coasts of Sicily, Naples and Spain. But all traders belonging to nations which did not pay tribute in order to secure immunity were liable to be taken at sea. The payment of this tribute, disguised as presents or ransoms, did not always secure safety. The most powerful states in Europe condescended to make payments to them and to tolerate their insults. Religious orders—the Redemptionists and Lazarists — were engaged in working for the redemption of captives and large legacies were left for that purpose in many countries. The continued existence of this African piracy was indeed a disgrace to Europe, for it was due to the jealousies of the powers themselves. France encouraged them during their rivalry with Spain and when she had no further need of them they were supported against her by Great Britain and Holland. In the 18th century, British public men were not ashamed to say that Barbary piracy was a useful check on the competition of the weaker Mediterranean nations in the carrying trade. When Lord Exmouth sailed to coerce Algiers in 1816, he expressed doubts in a private letter whether the suppression of piracy would be acceptable to the trading community. Every power was, indeed, desirous to secure immunity for itself and more or less ready to compel Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, Sale and the next to respect its trade and subjects. In 1655 the British admiral, Robert Blake, was sent to teach them a lesson, and he gave the Tunisians a severe beating. A long series of expeditions was undertaken by the British fleet during the reign of Charles II, sometimes singled-handed, sometimes in combination with the Dutch. In 1682 and 1683, the French bombarded Algiers. On the second occasion the Algerines blew the French consul from a gun during the action. An extensive list of such punitive expeditions could be made out, down to the American operations of 1801-05 and 1815. But in no case was the attack pushed home, and it rarely happened that the aggrieved European state refused in the end to make a money payment in order to secure peace. The frequent wars among them gave the pirates numerous opportunities of breaking their engagements, of which they never failed to take advantage.[11]

Some of them were renegades or Moriscos. Their usual ship was the galley with slaves or prisoners at the oars. Two examples of these renegades are Süleyman Reis, "De Veenboer", who became admiral of the Algerian corsair fleet in 1617, and his quartermaster Murat Reis, born Jan Janszoon van Haarlem. Both worked for the notorious corsair Simon the Dancer, who owned a palace. These pirates were all originally Dutch. The Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter unsuccessfully tried to end their piracy.

United States and the Barbary Wars

In 1783 the United States made peace with, and gained recognition from, the British monarchy, and in 1784 the first American ship was seized by pirates from Morocco. After six months of negotiation, a treaty was signed, $60,000 cash was paid, and trade began. Morocco was the first independent nation to recognize the United States, in 1778.[13] But Algeria was different. In 1784 two ships (the Maria of Boston and the Dauphin of Philadelphia) were seized, everything sold and their crews ordered to build port fortifications.

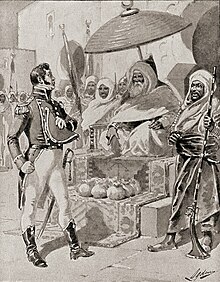

In 1786, Thomas Jefferson, then the ambassador to France, and John Adams, then the ambassador to Britain, met in London with Sidi Haji Abdul Rahman Adja, the ambassador to Britain from Tripoli. The Americans asked Adja why his government was hostile to American ships, even though there had been no provocation. The ambassador's response was reported to the Continental Congress:

- That it was founded on the Laws of their Prophet, that it was written in their Qur'an, that all nations who should not have acknowledged their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as Prisoners, and that every Musselman [Muslim] who should be slain in Battle was sure to go to Paradise.[14]Must give a better reference for such a claim

American ships sailing in the Mediterranean chose to travel close to larger convoys of other European powers who had bribed the pirates. Payments in ransom and tribute to the Barbary states amounted to 20% of United States government annual revenues in 1800.[15] In the early 1800s, President Thomas Jefferson proposed a league of smaller nations to patrol the area, but the United States could not contribute. For the prisoners, Algeria wanted $60,000 dollars, while America offered only $4,000. Jefferson said a million dollars would buy them off, but Congress would only appropriate $80,000. For eleven years, Americans who lived in Algeria lived as slaves to Algerian Moors. For a while, Portugal was patrolling the Straits of Gibraltar and preventing Barbary Pirates from entering the Atlantic. But they made a cash deal with the pirates, and they were again sailing into the Atlantic and engaging in piracy. By late 1793, a dozen American ships had been captured, goods stripped and everyone enslaved. Portugal had offered some armed patrols, but American merchants needed an armed American presence to sail near Europe. After some serious debate, the United States Navy was born in March 1794. Six frigates were authorized, and so began the construction of the United States, the Constellation, the Constitution and three other frigates.

This new military presence helped to stiffen American resolve to resist the continuation of tribute payments, leading to the two Barbary Wars along the North African coast: the First Barbary War from 1801 to 1805[16] and the Second Barbary War in 1815. It was not until 1815 that naval victories ended tribute payments by the U.S., although some European nations continued annual payments until the 1830s.

The United States Marine Corps actions in these wars led to the line "to the shores of Tripoli" in the opening of the Marine Hymn. Due to the hazards of boarding hostile ships, Marines' uniforms had a leather high collar to protect against cutlass slashes. This led to the nickname Leatherneck for U.S. Marines.[17]

After 1815

After the general pacification of 1815, the suppression of African piracy was universally felt to be a necessity. The sacking of Palma on the island of Sardinia by a Tunisian squadron, which carried off 158 inhabitants, roused widespread indignation. Other influences were at work to bring about their extinction. The United Kingdom had acquired Malta and the Ionian Islands and now had many Mediterranean subjects. It was also engaged in pressing the other European powers to join with it in the suppression of the slave trade which the Barbary states practised on a large scale and at the expense of Europe. The suppression of the trade was one of the objects of the Congress of Vienna. The United Kingdom was called on to act for Europe, and in 1816 Lord Exmouth was sent to obtain treaties from Tunis and Algiers. His first visit produced diplomatic documents and promises and he sailed for England. While he was negotiating, a number of British subjects had been brutally ill-treated at Bona, without his knowledge. The British government sent him back to secure reparation, and on the 17th of August, in combination with a Dutch squadron under Admiral Van de Capellen, he administered a smashing bombardment to Algiers. The lesson terrified the pirates both of that city and of Tunis into giving up over 3,000 prisoners and making fresh promises. Within a short time, however, Algiers renewed its piracies and slave-taking, though on a smaller scale, and the measures to be taken with it were discussed at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818. In 1824 another British fleet under Admiral Sir Harry Neal again bombarded Algiers. The great pirate city was not in fact thoroughly tamed till its conquest by France in 1830.[11]

Barbary pirates in literature

Barbary pirates appear in a number of famous novels, including Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, père, The Sea Hawk by Rafael Sabatini, The Algerine Captive by Royall Tyler, Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian, the Baroque Cycle by Neal Stephenson, The Walking Drum by Louis Lamour and Doctor Doolittle by Hugh Lofting. Miguel de Cervantes was captive in the bagnio of Algiers, and reflected his experience in some of his books, including Don Quixote.

Famous Barbary Corsairs

- Barbarossa Hayreddin Paşa

- Turgut Reis

- Piyale Paşa

- Kemal Reis

- Piri Reis

- Seydi Ali Reis

- Salih Reis

- Kurtoğlu Muslihiddin Reis

- Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis

- Oruç Reis

- Gedik Ahmed Paşa

- Uluç Ali Reis

- Murat Reis the Elder

- Çaka Bey

- Murat Reis the Younger

- Yusuf Reis

See also

- Islamic Raids

- Knights of Rhodes

- First Barbary War

- Second Barbary War

- Barbary treaties

- List of Ottoman & Barbary raids

- Stephen Decatur

- USS Hornet

- Dey of Algiers

- Lundy - captured by Barbary pirates.

- Miguel de Cervantes - spent five years as a slave in Algiers.

- Barbary Slave Trade

- Islam and slavery

- Spanish Empire

- Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman-Habsburg wars

- History of the Ottoman Navy

- Mathurin d’Aux de Lescout

Further reading

- London, Joshua E. Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. ISBN 978-0471444152

- The Stolen Village Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates by Des Ekin ISBN 978-0862789558

- Knights Hospitaller of St. John - Order of St John of Jerusalem Malta

- Pirates of the Mediterranean

- Hitchens, Christopher (Spring 2007). "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". City Journal. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Lafi (Nora), Une ville du Maghreb entre ancien régime et réformes ottomanes. Genèse des institutions municipales à Tripoli de Barbarie (1795–1911), Paris: L'Harmattan, 2002, 305 pp.

Notes

- ^ British Slaves on the Barbary Coast

- ^ Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates by Christopher Hitchens, City Journal Spring 2007

- ^ The mysteries and majesties of the Aeolian Islands

- ^ Vieste

- ^ History of Menorca

- ^ When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed

- ^ Watch-towers and fortified towns

- ^ Rees Davies, British Slaves on the Barbary Coast, BBC, 1 July, 2003

- ^ Barbary Pirates - Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Reference needed

- ^ a b c d e This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barbary Pirates". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Reference needed

- ^ Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. "Outbreak". The Wars of the Barbary Pirates: To the Shores of Tripoli: The Birth of the US Navy and Marines. Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 1-8460-3030-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ America's Earliest Terrorists: Lessons from America's First War against Islamic Terror

- ^ Oren, Michael B. (2005-11-03). "The Middle East and the Making of the United States, 1776 to 1815". Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ^ The Mariners' Museum : The Barbary Wars, 1801-1805

- ^ Chenoweth, USMCR (Ret.), Col. H. Avery (2005). Semper fi: The Definitive Illustrated History of the U.S. Marines. New York: Main Street. ISBN 1-4027-3099-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

References

- A History of Pirates by Angus Konstam

- Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. Thomas Dunne, 2003

- Forester, C. S. The Barbary Pirates. Random House, 1953

- Leiner, Frederick C. The End of Barbary Terror: America's 1815 War against the Pirates of North Africa. Oxford University Press, 2006

- Lambert, Frank. The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World. Hill & Wang, 2005

- World Navies

Iceland sources

Barbary To and Fro by Jens Riise Kristensen, Ørby publishing 2005. (www.oerby.dk)