Copper: Difference between revisions

m →Pure water and air/oxgyen: grammar |

m →Electrical properties: grammar |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

===Electrical properties=== |

===Electrical properties=== |

||

[[File:Busbars.jpg|right|thumb|Copper electrical [[busbar]]s distributing power to a large building.]] |

[[File:Busbars.jpg|right|thumb|Copper electrical [[busbar]]s distributing power to a large building.]] |

||

At 59.6 × 10<sup>6</sup> [[Siemens (unit)|S]]/m copper has the second highest electrical conductivity of any element after silver. This high value is due to virtually all the valence electrons (one per atom) taking part in conduction. The resulting [[free electron]]s in the copper amounting to a huge charge density of 13.6x10<sup>9</sup> C/m<sup>3</sup>. This high charge density is responsible for the rather slow [[drift velocity]] of currents in copper cable (drift velocity may be calculated as the ratio of current density to charge density). For instance, at a current density of 5x10<sup>6</sup> A/m<sup>2</sup> (typically, the maximum current density present in household wiring and grid distribution) the drift velocity is just a little over ⅓ mm/s.<ref>Seymour, J, ''Physical Electronics'', pp25-27,53-54, Pitman Publishing, 1972.</ref> |

At 59.6 × 10<sup>6</sup> [[Siemens (unit)|S]]/m copper has the second highest electrical conductivity of any element, just after silver. This high value is due to virtually all the valence electrons (one per atom) taking part in conduction. The resulting [[free electron]]s in the copper amounting to a huge charge density of 13.6x10<sup>9</sup> C/m<sup>3</sup>. This high charge density is responsible for the rather slow [[drift velocity]] of currents in copper cable (drift velocity may be calculated as the ratio of current density to charge density). For instance, at a current density of 5x10<sup>6</sup> A/m<sup>2</sup> (typically, the maximum current density present in household wiring and grid distribution) the drift velocity is just a little over ⅓ mm/s.<ref>Seymour, J, ''Physical Electronics'', pp25-27,53-54, Pitman Publishing, 1972.</ref> |

||

===Corrosion=== |

===Corrosion=== |

||

Revision as of 22:07, 20 April 2009

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Red-orange metallic luster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cu) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copper in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1357.77 K (1084.62 °C, 1984.32 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2835 K (2562 °C, 4643 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 8.935 g/cm3 [3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 8.02 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.26 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 300.4 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.440 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +2 −2,? 0,[4] +1,[5] +3,[5] +4[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 128 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 132±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 140 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) (cF4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 361.50 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 16.64×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 401 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 16.78 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −5.46×10−6 cm3/mol[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 110–128 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 48 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 140 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (annealed) 3810 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 343–369 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 235–878 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-50-8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Cyprus, principal mining place in Roman era (Cyprium) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Middle East (9000 BC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | "Cu": from Latin cuprum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of copper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copper (Template:PronEng) is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (Template:Lang-la) and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is rather soft and malleable and a freshly-exposed surface has a pinkish or peachy color. Gold, caesium and copper are the only metallic elements with a natural color other than gray or white. It is used as a thermal conductor, an electrical conductor, a building material, and a constituent of various metal alloys.

Copper is an essential trace nutrient to all higher plant and animal life. In animals, including humans, it is found widely in tissues, with concentration in liver, muscle, and bone. It functions as a co-factor in various enzymes and in copper-based pigments. Some molluscs have blue-green blood resulting from a copper compound which they use to transport oxygen, instead of heme. In sufficient amounts, copper salts can be poisonous.

Copper has played a significant part in the history of mankind, which has used the easily accessible uncompounded metal and its alloys for thousands of years. Evidence has been preserved from several early civilizations of the use of copper. In the Roman era, copper was principally mined on Cyprus, hence the origin of the name of the metal as Cyprium, "metal of Cyprus", later shortened to Cuprum.

Some countries, such as Chile and the United States, still have sizable reserves of the metal which are extracted through large open pit mines. However, like tin, there may be insufficient reserves to sustain current rates of consumption.[9] High demand relative to supply caused a price spike in the 2000s.[10]

Copper has a significant presence in decorative art. It can also be used as an anti-germ surface that can add to the anti-bacterial and antimicrobial features of buildings such as hospitals.[11]

History

Copper Age

Copper, as native copper, is one of the few metals to occur naturally as an un-compounded mineral. Copper was known to some of the oldest civilizations on record, and has a history of use that is at least 10,000 years old[citation needed]. Some estimates of copper's discovery place this event around 9000 BC in the Middle East.[12] A copper pendant was found in what is now northern Iraq that dates to 8700 BC.[citation needed] It is probable that gold and meteoritic iron were the only metals used by humans before copper.[13] By 5000 BC, there are signs of copper smelting: the refining of copper from simple copper compounds such as malachite or azurite. Among archaeological sites in Anatolia, Çatal Höyük (~6000 BC) features native copper artifacts and smelted lead beads, but no smelted copper. Can Hasan (~5000 BC) had access to smelted copper but the oldest smelted copper artifact found (a copper chisel from the chalcolithic site of Prokuplje in Serbia) has pre-dated Can Hasan by 500 years. The smelting facilities in the Balkans appear to be more advanced than the Turkish forges found at a later date, so it is quite probable that copper smelting originated in the Balkans. Investment casting was realized in 4500-4000 BCE in Southeast Asia.[12]

Copper smelting appears to have been developed independently in several parts of the world. In addition to its development in the Balkans by 5500 BC, it was developed in China before 2800 BC, in the Andes around 2000 BC, in Central America around 600 AD, and in West Africa around 900 AD.[14] Copper is found extensively in the Indus Valley Civilization by the 3rd millennium BC.[15] In Europe, Ötzi the Iceman, a well-preserved male dated to 3300-3200 BC, was found with an axe with a copper head 99.7% pure. High levels of arsenic in his hair suggest he was involved in copper smelting. Over the course of centuries, experience with copper has assisted the development of other metals; for example, knowledge of copper smelting led to the discovery of iron smelting.

In the Americas production in the Old Copper Complex, located in present day Michigan and Wisconsin, was dated back to between 6000 to 3000 BC.[16]

Bronze Age

Alloying of copper with zinc or tin to make brass or bronze was practiced soon after the discovery of copper itself. There exist copper and bronze artifacts from Sumerian cities that date to 3000 BC,[citation needed] and Egyptian artifacts of copper and copper-tin alloys nearly as old. In one pyramid,[citation needed] a copper plumbing system was found that is 5000 years old. The Egyptians found that adding a small amount of tin made the metal easier to cast, so copper-tin (bronze) alloys were found in Egypt almost as soon as copper was found. Very important sources of copper in the Levant were located in Timna valley (Negev, now in southern Israel) and Faynan (biblical Punon, Jordan).[17]

By 2000 BC, Europe was using bronze.[citation needed] The use of bronze became so widespread in Europe approximately from 2500 BC to 600 BC that it has been named the Bronze Age. The transitional period in certain regions between the preceding Neolithic period and the Bronze Age is termed the Chalcolithic ("copper-stone"), with some high-purity copper tools being used alongside stone tools. Brass (copper-zinc alloy) was known to the Greeks, but only became a significant supplement to bronze during the Roman empire.

During the Bronze Age, one copper mine at Great Orme in North Wales, extended for a depth of 70 metres.[18] At Alderley Edge in Cheshire, carbon dates have established mining at around 2280 to 1890 BC (at 95% probability).[19]

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In Greek the metal was known by the name chalkos (χαλκός). Copper was a very important resource for the Romans, Greeks and other ancient peoples. In Roman times, it became known as aes Cyprium (aes being the generic Latin term for copper alloys such as bronze and other metals, and Cyprium because so much of it was mined in Cyprus). From this, the phrase was simplified to cuprum, hence the English copper. Copper was associated with the goddess Aphrodite/Venus in mythology and alchemy, owing to its lustrous beauty, its ancient use in producing mirrors, and its association with Cyprus, which was sacred to the goddess. In astrology, alchemy the seven heavenly bodies known to the ancients were associated with seven metals also known in antiquity, and Venus was assigned to copper.[20]

Britain's first use of brass occurred some time around the 3rd - 2nd century B.C. In North America, copper mining began with marginal workings by Native Americans. Native copper is known to have been extracted from sites on Isle Royale with primitive stone tools between 800 and 1600.[21]

Copper metallurgy was flourishing in South America, particularly in Peru around the beginning of the first millennium AD. Copper technology proceeded at a much slower rate on other continents. Africa's major location for copper reserves is Zambia. Copper burial ornamentals dated from the 15th century have been uncovered, but the metal's commercial production did not start until the early 1900s. Australian copper artifacts exist, but they appear only after the arrival of the Europeans; the aboriginal culture apparently did not develop their own metallurgical abilities.

Crucial in the metallurgical and technological worlds, copper has also played an important cultural role, particularly in currency. Romans in the 6th through 3rd centuries B.C. used copper lumps as money. At first, just the copper itself was valued, but gradually the shape and look of the copper became more important. Julius Caesar had his own coins, made from a copper-zinc alloy, while Octavianus Augustus Caesar's) coins were made from Cu-Pb-Sn alloys.

The gates of the Temple of Jerusalem used Corinthian bronze made by depletion gilding. Corinthian bronze was most prevalent in Alexandria, where alchemy is thought to have begun. In ancient India (before 1000 B.C.), copper was used in the holistic medical science Ayurveda for surgical instruments and other medical equipment. Ancient Egyptians (~2400 B.C.) used copper for sterilizing wounds and drinking water, and as time passed, (~1500 B.C.) for headaches, burns, and itching. Hippocrates (~400 B.C.) used copper to treat leg ulcers associated with varicose veins. Ancient Aztecs fought sore throats by gargling with copper mixtures.

Copper is also the part of many rich stories and legends, such as that of Iraq's Baghdad Battery. Copper cylinders soldered to lead, which date back to 248 B.C. to 226 A.D, resemble a galvanic cell, leading people to believe this may have been the first battery. This claim has so far not been substantiated.

The Bible also refers to the importance of copper: "Men know how to mine silver and refine gold, to dig iron from the earth and melt copper from stone" (Job. 28:1-2).

Modern period

Throughout history, copper's use in art has extended far beyond currency. Vannoccio Biringuccio, Giorgio Vasari and Benvenuto Cellini are three Renaissance sculptors from the mid 1500s, notable for their work with bronze. From about 1560 to about 1775, thin sheets of copper were commonly used as a canvas for paintings. Silver plated copper was used in the pre-photograph known as the daguerreotype. The Statue of Liberty, dedicated on October 28, 1886, was constructed of copper thought to have come from French-owned mines in Norway.

Plating was a technology that began started in the mid 1600s in some areas. One common use for copper plating, widespread in the 1700s, was the sheathing of ships' hulls. Copper sheathing could be used to protect wooden hulled ships from algae, and from the shipworm "toredo", a saltwater clam. The ships of Christopher Columbus were among the earliest to have this protection.[22]

In 1801 Paul Revere established America's first copper rolling mill in Canton, Massachusetts. In the early 1800s, it was discovered that copper wire could be used as a conductor, but it wasn't until 1990 that copper, in oxide form, was discovered for use as a superconducting material. The German scientist Gottfried Osann invented powder metallurgy of copper in 1830 while determining the metal's atomic weight. Around then it was also discovered that the amount and type of alloying element (e.g. tin) would affect the tones of bells, allowing for a variety of rich sounds, leading to bell casting, another common use for copper and its alloys.

The Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg was the first modern electroplating plant.[citation needed]

Flash smelting, which is still used today, was developed in Europe in order to make the smelting process more energy efficient. In 1908, in Outokumpu, Finland, a large deposit of copper ore was discovered, which eventually led to the development of flash smelting.

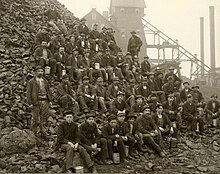

Copper has been pivotal in the economic and sociological worlds, notably disputes involving copper mines. The 1906 Cananea Strike in Mexico dealt with issues of work organization. The Teniente copper mine (1904-1951) raised political issues about capitalism and class structure. Japan's largest copper mine, the Ashio mine, was the site of a riot in 1907. The Arizona miners' strike of 1938 dealt with American labor issues including the "right to strike".

Characteristics

Color

Copper has a reddish, orangish, or brownish color because a thin layer of tarnish (including oxides) gradually forms on its surface when gases (especially oxygen) in the air react with it. But pure copper, when fresh, is actually a pinkish or peachy metal. Copper, caesium and gold are the only three elemental metals with a natural color other than gray or silver.[23] The usual gray color of metals depends on their "electron sea" that is capable of absorbing and re-emitting photons over a wide range of frequencies. Copper has its characteristic color because of its unique band structure. By Madelung's rule the 4s subshell should be filled before electrons are placed in the 3d subshell but copper is an exception to the rule with only one electron in the 4s subshell instead of two. The energy of a photon of blue or violet light is sufficient for a d band electron to absorb it and transition to the half-full s band. Thus the light reflected by copper is missing some blue/violet components and appears red. This phenomenon is shared with gold which has a corresponding 5s/4d structure.[24] In its liquefied state, a pure copper surface without ambient light appears somewhat greenish, a characteristic shared with gold. When liquid copper is in bright ambient light, it retains some of its pinkish luster.

When copper is burnt in oxygen it gives off a black oxide.

Group 11 of the periodic table

Copper occupies the same family of the periodic table as silver and gold, since they each have one s-orbital electron on top of a filled electron shell which forms metallic bonds. This similarity in electron structure makes them similar in many characteristics. All have very high thermal and electrical conductivity, and all are malleable metals. Among pure metals at room temperature, copper has the second highest electrical and thermal conductivity, after silver.[25]

Occurrence

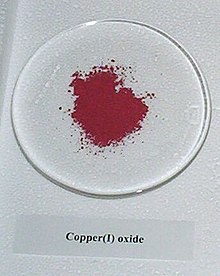

Copper can be found as native copper in mineral form (for example, in Michigan's Keewenaw Peninsula). Minerals such as the sulfides: chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bornite (Cu5FeS4), covellite (CuS), chalcocite (Cu2S) are sources of copper, as are the carbonates: azurite (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2) and malachite (Cu2CO3(OH)2) and the oxide: cuprite (Cu2O).

Mechanical properties

Copper is easily worked, being both ductile and malleable. The ease with which it can be drawn into wire makes it useful for electrical work in addition to its excellent electrical properties. Copper can be machined, although it is usually necessary to use an alloy for intricate parts, such as threaded components, to get really good machinability characteristics.[26] Good thermal conduction make it useful for heatsinks and in heat exchangers. Copper has good corrosion resistance, but not as good as gold. It has excellent brazing and soldering properties and can also be welded, although best results are obtained with gas metal arc welding.[27]

Copper is normally supplied, as with nearly all metals for industrial and commercial use, in a fine grained polycrystalline form. Polycrystalline metals have greater strength than monocrystalline forms, and the difference is greater for smaller grain (crystal) sizes. The reason is due to the inability of stress dislocations in the crystal structure to cross the grain boundaries.[28] The plastic deformation of polycrystal is similar to mild steel.[citation needed]

Electrical properties

At 59.6 × 106 S/m copper has the second highest electrical conductivity of any element, just after silver. This high value is due to virtually all the valence electrons (one per atom) taking part in conduction. The resulting free electrons in the copper amounting to a huge charge density of 13.6x109 C/m3. This high charge density is responsible for the rather slow drift velocity of currents in copper cable (drift velocity may be calculated as the ratio of current density to charge density). For instance, at a current density of 5x106 A/m2 (typically, the maximum current density present in household wiring and grid distribution) the drift velocity is just a little over ⅓ mm/s.[29]

Corrosion

Pure water and air/oxgyen

Copper is a metal that does not react with water (H2O), but the oxygen of the air will react slowly at room temperature to form a layer of brown-black copper oxide on copper metal.

It is important to note that in contrast to the oxidation of iron by wet air that the layer formed by the reaction of air with copper has a protective effect against further corrosion. On old copper roofs a green layer of copper carbonate, called verdigris, can often be seen. A notable example of this is on the Statue of Liberty.

In contact with other metals

Copper should not be in direct mechanical contact with metals of different electropotential (for example, a copper pipe joined to an iron pipe), especially in the presence of moisture, as the completion of an electrical circuit (for instance through the common ground) will cause the juncture to act as an electrochemical cell (like a single cell of a battery). The weak electrical currents themselves are harmless but the electrochemical reaction will cause the conversion of the iron to other compounds, eventually destroying the functionality of the union. This problem is usually solved in plumbing by separating copper pipe from iron pipe with some non-conducting segment (usually plastic or rubber).

Sulfide media

Copper metal does react with hydrogen sulfide- and sulfide-containing solutions. A series of different copper sulfides can form on the surface of the copper metal.

The Pourbaix diagram is very complex due to the existence of many different sulfides. In suphide containing solutions copper is less noble than hydrogen and will corrode. This can be observed in everyday life when copper metal surfaces tarnish after exposure to air which contains sulfur compounds.

Ammonia media

Copper is slowly dissolved in oxygen-containing ammonia solutions because the ammonia forms water-soluble copper complexes. The formation of these complexes causes the corrosion to become more thermodynamically favored than the corrosion of copper in an identical solution that does not contain the ammonia.

Chloride media

Copper reacts with a combination of oxygen and hydrochloric acid to form a series of copper chlorides. Copper(II) chloride (green/blue) when boiled with copper metal undergoes a Symproportionation reaction to form white copper(I) chloride.

Germicidal effect

Copper is germicidal, via the oligodynamic effect. For example, brass doorknobs disinfect themselves of many bacteria within a period of eight hours.[30] Antimicrobial properties of copper are effective against MRSA,[31] Escherichia coli[32] and other pathogens.[33][34][35] In colder temperature, longer time is required to kill bacteria.

Copper has the intrinsic ability to kill a variety of potentially harmful pathogens. On February 29, 2008, the United States EPA registered 275 alloys, containing greater than 65% nominal copper content, as antimicrobial materials[36]. Registered alloys include pure copper, an assortment of brasses and bronzes, and additional alloys. EPA-sanctioned tests using Good Laboratory Practices were conducted in order to obtain several antimicrobial claims valid against: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Enterobacter aerogenes, Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The EPA registration allows the manufacturers of these copper alloys to legally make public health claims as to the health effects of these materials. Several of the aforementioned bacteria are responsible for a large portion of the nearly two million hospital-acquired infections contracted each year in the United States[37]. Frequently touched surfaces in hospitals and public facilities harbor bacteria and increase the risk for contracting infections. Covering touch surfaces with copper alloys can help reduce microbial contamination associated with hospital-acquired-infections on these surfaces.

Isotopes

Copper has 29 distinct isotopes ranging in atomic mass from 52 to 80. Two of these, 63Cu and 65Cu, are stable and occur naturally, with 63Cu comprising approximately 69% of naturally occurring copper.[38]

The other 27 isotopes are radioactive and do not occur naturally. The most stable of these is 67Cu with a half-life of 61.83 hours. The least stable is 54Cu with a half-life of approximately 75 ns. Unstable copper isotopes with atomic masses below 63 tend to undergo β+ decay, while isotopes with atomic masses above 65 tend to undergo β− decay. 64Cu decays by both β+ and β−.[38]

68Cu, 69Cu, 71Cu, 72Cu, and 76Cu each have one metastable isomer. 70Cu has two isomers, making a total of 7 distinct isomers. The most stable of these is 68mCu with a half-life of 3.75 minutes. The least stable is 69mCu with a half-life of 360 ns.[38]

Production

Output

In 2005, Chile was the top mine producer of copper with at least one-third world share followed by the USA, Indonesia and Peru, reports the British Geological Survey.

Most copper ore is mined or extracted as copper sulfides from large open pit mines in porphyry copper deposits that contain 0.4 to 1.0 percent copper. Examples include: Chuquicamata in Chile and El Chino Mine in New Mexico. The average abundance of copper found within crustal rocks is approximately 68 ppm by mass, and 22 ppm by atoms.

The Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries (CIPEC), defunct since 1992, once tried to play a similar role for copper as OPEC does for oil, but never achieved the same influence, not least because the second-largest producer, the United States, was never a member. Formed in 1967, its principal members were Chile, Peru, Zaire, and Zambia.

The copper price has quintupled from the 60-year low in 1999, rising from US$0.60 per pound (US$1.32/kg) in June 1999 to US$3.75 per pound (US$8.27/kg) in May 2006, where it dropped to US$2.40 per pound (US$5.29/kg) in February 2007 then rebounded to US$3.50 per pound (US$7.71/kg = £3.89 = €5.00) in April 2007.[39] By early February 2009, however, weakening global demand and a steep fall in commodity prices since the previous year's highs had left copper prices at US$1.51 per pound.[40]

The Earth has an estimated 61 years of copper reserves remaining.[41] Environmental analyst, Lester Brown, however, has suggested copper might run out within 25 years based on a reasonable extrapolation of 2% growth per year.[42]

Copper has been in use at least 10,000 years, but more than 95 percent of all copper ever mined and smelted has been extracted since 1900. And as India and China race to catch up with the West, copper supplies are getting tight.[43] Copper is among the most important industrial metals. Like fossil fuels, copper is a finite resource. Peak copper is the point in time at which the maximum global copper production rate is reached, according to Hubbert peak theory, the rate of production enters its terminal decline.

Methods

Applications

Copper is malleable and ductile and is a good conductor of both heat and electricity.

The purity of copper is expressed as 4N for 99.99% pure or 7N for 99.99999% pure. The numeral gives the number of nines after the decimal point when expressed as a decimal (e.g. 4N means 0.9999, or 99.99%). Copper is often too soft for its applications, so it is incorporated in numerous alloys. For example, brass is a copper-zinc alloy, and bronze is a copper-tin alloy.[44]

It is used extensively, in products such as:

- including water supply.

- used extensively in refrigeration and air conditioning equipment because of its ease of fabrication and soldering.

Electrical applications

- Copper wire.

- Oxygen-free copper.

- Electromagnets.

- Printed circuit boards.

- Lead free solder, alloyed with tin.

- Electrical machines, especially electromagnetic motors, generators and transformers.

- Electrical relays, electrical busbars and electrical switches.

- Vacuum tubes, cathode ray tubes, and the magnetrons in microwave ovens.

- Wave guides for microwave radiation.

- Integrated circuits, increasingly replacing aluminium because of its superior electrical conductivity.

- As a material in the manufacture of computer heat sinks, as a result of its superior heat dissipation capacity to aluminium.

Architecture / Industry

- Copper has been used as water-proof roofing material since ancient times, giving many old buildings their greenish roofs and domes. Initially copper oxide forms, replaced by cuprous and cupric sulfide, and finally by copper carbonate. The final carbonate patina is highly resistant to corrosion.[45]

- Statuary: The Statue of Liberty, for example, contains 179,220 pounds (81.3 tonnes) of copper.

- Alloyed with nickel, e.g. cupronickel and Monel, used as corrosive resistant materials in shipbuilding.

- Watt's steam engine firebox due to superior heat dissipation.

- Copper nails were used in making oast cowls.

- Copper compounds in liquid form are used as a wood preservative, particularly in treating original portion of structures during restoration of damage due to dry rot.

- Copper wires may be placed over non-conductive roofing materials to discourage the growth of moss. (Zinc may also be used for this purpose.)

Household products

- Copper plumbing fittings and compression tubes.

- Doorknobs and other fixtures in houses.

- Roofing, guttering, and rainspouts on buildings.

- In cookware, such as frying pans.

- Some older flatware: (knives, forks, spoons) contains some copper if made from EPNS (see nickel silver).

- Sterling silver, if it is to be used in dinnerware, must contain a few percent copper.

- Copper water heating cylinders

- Copper Range Hoods

- Copper Bath Tubs

- Copper Counters

- Copper Sinks

- Copper slug tape

Coinage

- As a component of coins, often as cupronickel alloy, or some form of brass or bronze.

- Coins in the following countries all contain copper: European Union (Euro),[46] United States,[47] United Kingdom (sterling),[48] Australia[49] and New Zealand.[50]

- U.S. Nickels are 75.0% copper by weight and only 25.0% nickel.[47]

Biomedical applications

- As a biostatic surface in hospitals, and to line parts of ships to protect against barnacles and mussels, originally used pure, but superseded by Muntz metal. Bacteria will not grow on a copper surface because it is biostatic. Copper doorknobs are used by hospitals to reduce the transfer of disease, and Legionnaires' disease is suppressed by copper tubing in air-conditioning systems.

- Copper(II) sulfate is used as a fungicide and as algae control in domestic lakes and ponds. It is used in gardening powders and sprays to kill mildew.

- Copper-62-PTSM, a complex containing radioactive copper-62, is used as a Positron emission tomography radiotracer for heart blood flow measurements.

- Copper-64 can be used as a positron emission tomography radiotracer for medical imaging. When complexed with a chelate it can be used to treat cancer through radiation therapy.

Chemical applications

- Compounds, such as Fehling's solution, have applications in chemistry.

- As a component in ceramic glazes, and to colour glass.

Other

- Musical instruments, especially brass instruments and timpani.

- Class D Fire Extinguisher, used in powder form to extinguish lithium fires by covering the burning metal and performing similar to a heat sink.

- Textile fibers to create antimicrobial protective fabrics.[51]

- Weaponry:

- Small arms ammunition commonly uses copper as a jacketing material around the bullet core.

- Copper is also commonly used as a case material, in the form of brass.

- Copper is used as a liner in shaped-charge armour-piercing warheads.

- Copper is frequently used in electroplating, usually as a base for other metals such as Nickel.

Alloys

Numerous copper alloys exist, many with important historical and contemporary uses. Speculum metal and bronze are alloys of copper and tin. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Monel metal, also called cupronickel, is an alloy of copper and nickel. While the metal "bronze" usually refers to copper-tin alloys, it also is a generic term for any alloy of copper, such as aluminium bronze, silicon bronze, and manganese bronze. Copper is one of the most important constituents of carat silver and gold alloys and carat solders used in the jewelry industry, modifying the color, hardness and melting point of the resulting alloys.[52]

Compounds

Common oxidation states of copper include the less stable copper(I) state, Cu+; and the more stable copper(II) state, Cu2+, which forms blue or blue-green salts and solutions. Under unusual conditions, a 3+ state and even an extremely rare 4+ state can be obtained. Using old nomenclature for the naming of salts, copper(I) is called cuprous, and copper(II) is cupric. In oxidation copper is mildly basic.

Copper(II) carbonate is green from which arises the unique appearance of copper-clad roofs or domes on some buildings. Copper(II) sulfate forms a blue crystalline pentahydrate which is perhaps the most familiar copper compound in the laboratory. It is used as a fungicide, known as Bordeaux mixture.

There are two stable copper oxides, copper(II) oxide (CuO) and copper(I) oxide (Cu2O). Copper oxides are used to make yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7-δ) or YBCO which forms the basis of many unconventional superconductors.

- Copper(I) compounds: copper(I) chloride, copper(I) bromide, copper(I) iodide, copper(I) oxide.

- Copper(II) compounds: copper(II) acetate, copper(II) carbonate, copper(II) chloride, copper(II) hydroxide, copper(II) nitrate, copper(II) oxide, copper(II) sulfate, copper(II) sulfide, copper(II) tetrafluoroborate, copper(II) triflate.

- Copper(III) compounds, rare: potassium hexafluorocuprate (K3CuF6)

- Copper(IV) compounds, extremely rare: caesium hexafluorocuprate (Cs2CuF6)

Tests for copper(II) ion

Add aqueous sodium hydroxide. A blue precipitate of copper(II) hydroxide should form.

Ionic equation:

- Cu2+(aq) + 2OH−(aq) → Cu(OH)2(s)

The full equation shows that the reaction is due to hydroxide ions deprotonating the hexaaquacopper (II) complex:

- [Cu(H2O)6]2+(aq) + 2 OH−(aq) → Cu(H2O)4(OH)2(s) + 2 H2O (l)

Adding ammonium hydroxide (aqueous ammonia) causes the same precipitate to form. It then dissolves upon adding excess ammonia, to form a deep blue ammonia complex, tetraamminecopper(II).

Ionic equation:

- Cu(H2O)4(OH)2(s) + 4 NH3(aq) → [Cu(H2O)2(NH3)4]2+(aq) + 2H2O(l) + 2 OH−(aq)

A more delicate test than ammonia is potassium ferrocyanide, which gives a brown precipitate with copper salts.

Biological role

Copper is essential in all plants and animals. The human body normally contains copper at a level of about 1.4 to 2.1 mg for each kg of body weight.[53] Copper is distributed widely in the body and occurs in liver, muscle and bone. Copper is transported in the bloodstream on a plasma protein called ceruloplasmin. When copper is first absorbed in the gut it is transported to the liver bound to albumin. Copper metabolism and excretion is controlled delivery of copper to the liver by ceruloplasmin, where it is excreted in bile.

Copper is found in a variety of enzymes, including the copper centers of cytochrome c oxidase and the enzyme superoxide dismutase (containing copper and zinc). In addition to its enzymatic roles, copper is used for biological electron transport. The blue copper proteins that participate in electron transport include azurin and plastocyanin. The name "blue copper" comes from their intense blue color arising from a ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) absorption band around 600 nm.

Most molluscs and some arthropods such as the horseshoe crab use the copper-containing pigment hemocyanin rather than iron-containing hemoglobin for oxygen transport, so their blood is blue when oxygenated rather than red.[54]

It is believed that zinc and copper compete for absorption in the digestive tract so that a diet that is excessive in one of these minerals may result in a deficiency in the other. The RDA for copper in normal healthy adults is 0.9 mg/day. On the other hand, professional research on the subject recommends 3.0 mg/day.[55] Because of its role in facilitating iron uptake, copper deficiency can often produce anemia-like symptoms. In humans, the symptoms of Wilson's disease are caused by an accumulation of copper in body tissues.

Chronic copper depletion leads to abnormalities in metabolism of fats, high triglycerides, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fatty liver disease and poor melanin and dopamine synthesis causing depression and sunburn. Food rich in copper should be eaten away from any milk or egg proteins as they block absorption.

Toxicity

Toxicity can occur from eating acidic food that has been cooked with copper cookware. Cirrhosis of the liver in children (Indian Childhood Cirrhosis) has been linked to boiling milk in copper cookware. The Merck Manual states that recent studies suggest that a genetic defect is associated with this cirrhosis.[57] Since copper is actively excreted by the normal body, chronic copper toxicosis in humans without a genetic defect in copper handling has not been demonstrated.[58] However, large amounts (gram quantities) of copper salts taken in suicide attempts have produced acute copper toxicity in normal humans. Equivalent amounts of copper salts (30 mg/kg) are toxic in animals[59]

Miscellaneous hazards

The metal, when powdered, is a fire hazard. At concentrations higher than 1 mg/L, copper can stain clothes and items washed in water.

See also

- Electroplating

- Copper mining and extraction:

- Native copper

- Companies: Anaconda Copper, Antofagasta PLC, Codelco, also Category:Copper mining companies

- Copper extraction techniques, also Smelter

- Peak copper

- Pipe corrosion and damage: Cold water pitting of copper tube, Erosion corrosion of copper water tubes

- Copper theft :Metal theft, also Operation Tremor

References

Notes

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Copper". CIAAW. 1969.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Moret, Marc-Etienne; Zhang, Limei; Peters, Jonas C. (2013). "A Polar Copper–Boron One-Electron σ-Bond". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (10): 3792–3795. doi:10.1021/ja4006578. PMID 23418750.

- ^ a b c Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-03.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ "Earth's Limited Supply of Metals Raises Concern". Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Copper Grade A Prices on The London Metal Exchange". Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Barnaby J. Feder (March 26, 2008). "Regulators Stamp Copper as a Germ Killer". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "CSA - Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper<!- Bot generated title ->". Csa.com. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "29 Copper<!- Bot generated title ->". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ Richard Cowen, Essays on Geology, History, and People, Chapter 3: "Fire and Metals: Copper".

- ^ harappa.com (Web archive)

- ^ Thomas C. Pleger (2000). "The Old Copper Complex of the Western Great Lakes". UW-Fox Valley Anthropology. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ J.M. Tebes (2007). "A Land whose Stones are Iron, and out of whose Hills You can Dig Copper: The Exploitation and Circulation of Copper in the Iron Age Negev and Edom". DavarLogos. 6 (1).

- ^ O’Brien, W. (1997). Bronze Age Copper Mining in Britain and Ireland. Shire Publications Ltd. ISBN 0747803218.

- ^ Timberlake and Prag, 2005

- ^ T. A. Rickard (1932). "The Nomenclature of Copper and its Alloys". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 62: 281–290. doi:10.2307/2843960.

- ^ Susan R. Martin (1995). "The State of Our Knowledge About Ancient Copper Mining in Michigan". The Michigan Archaeologist. 41 (2–3): 119–138.

- ^ Copper History, retrieved 2008-09-04

- ^ Chambers, p. 312.

- ^ Manijeh Razeghi, Fundamentals of Solid State Engineering, pp154-156, Birkhäuser, 2006 ISBN 0387281525

- ^ Los Alamos National Laboratory - Copper

- ^ Davis, p266.

- ^ Joseph R. Davis, Copper and Copper Alloys, pp3-6, ASM International, 2001 ISBN 0871707268.

- ^ William F. Smith, Javad Hashemi, Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering, p223, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003 ISBN 0072921943.

- ^ Seymour, J, Physical Electronics, pp25-27,53-54, Pitman Publishing, 1972.

- ^ Phyllis J. Kuhn, Ph.D. (1983). "Doorknobs: A Source of Nosocomial Infection?". Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ Noyce JO, Michels H, Keevil CW (2006). "Potential use of copper surfaces to reduce survival of epidemic meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the healthcare environment". J. Hosp. Infect. 63 (3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2005.12.008. PMID 16650507.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Noyce JO, Michels H, Keevil CW (2006). "Use of copper cast alloys to control Escherichia coli O157 cross-contamination during food processing". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 (6): 4239–44. doi:10.1128/AEM.02532-05. PMID 16751537.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mehtar S, Wiid I, Todorov SD (2008). "The antimicrobial activity of copper and copper alloys against nosocomial pathogens and Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from healthcare facilities in the Western Cape: an in-vitro study". J. Hosp. Infect. 68 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2007.10.009. PMID 18069086.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gant VA, Wren MW, Rollins MS, Jeanes A, Hickok SS, Hall TJ (2007). "Three novel highly charged copper-based biocides: safety and efficacy against healthcare-associated organisms". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60 (2): 294–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm201. PMID 17567632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Noyce JO, Michels H, Keevil CW (2007). "Inactivation of influenza A virus on copper versus stainless steel surfaces". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 (8): 2748–50. doi:10.1128/AEM.01139-06. PMID 17259354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/factsheets/copper-alloy-products.htm

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/

- ^ a b c Audi, G (2003). "Nubase2003 Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties". Nuclear Physics A. 729. Atomic Mass Data Center: 3–128. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ^ Copper Trends: Live Metal Spot Prices, MetalSpotPrice.com

- ^ [1]

- ^ New Scientist. May 26, 2007.

- ^ Brown, Lester (2006). Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 109. ISBN 0393328317.

- ^ Andrew Leonard (2006-03-02). "Peak copper?". Salon - How the World Works. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ "Copper". American Elements. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Berg, Jan. "Why did we paint the library's roof?". Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ "The Euro - Born out of Copper". Copper Development Association. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ a b "Coin Specifications". United States Mint. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ "Demonetisation". The Royal Mint. 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Circulating Coin Designs". Royal Australian Mint. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Questions and answers". Change for the Better. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Antimicrobial Products that Shield Against Bacteria and Fungi". Cupron, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ http://www.utilisegold.com/jewellery_technology/colours/colour_alloys/

- ^ http://www.copper.org/consumers/health/papers/cu_health_uk/cu_health_uk.html Amount of copper in the normal human body, and other nutritional copper facts. Accessed April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Fun Facts". Horseshoe Crab. University of Delaware. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ National Research Council. Copper. In: Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington, D.C.: Food Nutrition Board, NRC/NAS, 1980: 151-154.

- ^ MedlinePlus > Copper poisoning Update Date: 2/3/2009. Updated by: A.D.A.M. Editorial Team: David Zieve, MD, MHA, Greg Juhn, MTPW, David R. Eltz. Previously reviewed by Stephen C Acosta, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portland VA Medical Center, Portland, OR. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network (10/30/2008). Retrieved on 18 Mars, 2009

- ^ "Merck Manulas -- Online Medical Library: Copper". Merck. November 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ^ http://www.copper.org/consumers/health/papers/cu_health_uk/cu_health_uk.html Amount of copper in the normal human body, and other nutritional copper facts. Accessed April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Pesticide Information Profile for Copper Sulfate". Cornell University. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

Bibliography

- Chambers, William; Chambers, Robert (1884), Chambers's Information for the People, vol. L (5th ed.), W. & R. Chambers.

Further reading

- "Copper: Technology & Competitiveness (Summary) Chapter 6: Copper Production Technology". Office of Technology Assessment. 2005.

- Current Medicinal Chemistry, Volume 12, Number 10, May 2005, pp. 1161–1208(48) Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress

- William D. Callister (2003). Materials Science and Engineering: an Introduction, 6th Ed. Table 6.1 p137.: Wiley, New York. ISBN 0471736961.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Material: Copper (Cu), bulk, MEMS and Nanotechnology Clearinghouse.

- Kim BE, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ (2008). "Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation". Nat. Chem. Biol. 4 (3): 176–85. doi:10.1038/nchembio.72. PMID 18277979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Copper transport disorders: an Instant insight from the Royal Society of Chemistry

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory - Copper and compounds fact sheet

- Copper Resource Page. Includes 12 PDF files detailing the material properties of various kinds of copper, as well as various guides and tools for the copper industry.

- The Copper Development Association has an extensive site of properties and uses of copper; it also maintains a web site dedicated to brass, a copper alloy.

- The Third Millennium Online page on Copper

- The WebElements page on Copper

- Comprehensive Data on Copper