Juneteenth: Difference between revisions

→Observation: some other states is not informal |

Replaced irrelevant UK abolition link with US link |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Juneteenth''', also known as '''Freedom Day''' or '''Emancipation Day''', is a holiday in the [[United States]] honoring [[African American]] heritage by commemorating the announcement of the [[ |

'''Juneteenth''', also known as '''Freedom Day''' or '''Emancipation Day''', is a holiday in the [[United States]] honoring [[African American]] heritage by commemorating the announcement of the [[Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|abolition]] of [[slavery]] in the [[U.S. State]] of [[Texas]] in 1865. Celebrated on June 19, the term is a [[portmanteau]] of ''June'' and ''nineteenth'', and is recognized as a state holiday in 36 states of the [[United States]].<ref name="hallenbeck2008" /><ref name="KS">{{cite web | url=http://www.juneteenth.us/pressrelease20.html | title=Kansas Becomes the 31st State to Recognize Juneteenth as a State Holiday | work=National Juneteenth Observance Foundation | accessdate=2009-05-29}}</ref> |

||

==Observation== |

==Observation== |

||

Revision as of 01:23, 28 June 2010

| Juneteenth | |

|---|---|

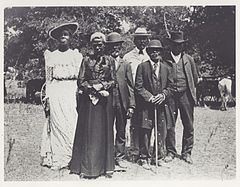

Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas, on June 19, 1900. | |

| Also called | Freedom Day or Emancipation Day |

| Observed by | Residents of the United States, especially African Americans |

| Type | Ethnic, historical |

| Significance | Emancipation of last remaining slaves in the United States |

| Observances | Exploration and celebration of African American history and heritage |

| Date | June 19 |

Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day, is a holiday in the United States honoring African American heritage by commemorating the announcement of the abolition of slavery in the U.S. State of Texas in 1865. Celebrated on June 19, the term is a portmanteau of June and nineteenth, and is recognized as a state holiday in 36 states of the United States.[1][2]

Observation

The state of Texas is widely considered the first U.S. state to begin Juneteenth celebrations with informal observances taking place for over a century, it has been an official state holiday since 1980. It is considered a "partial staffing holiday", meaning that state offices do not close, but some employees will be using a floating holiday to take the day off.[3] Its observance has spread to many other states, with a few celebrations even taking place in other countries.[4][5]

As of March 2010, 36 states[1] and the District of Columbia have recognized Juneteenth as either a state holiday or state holiday observance; these are Alaska,[5] Arizona, Arkansas, California,[5] Colorado, Connecticut,[5] Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas,[2] Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan,[6] Minnesota,[7] Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey,[5] New Mexico, New York,[5] North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas,[1] Vermont,[1] Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming.[8]

History

Though Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with an effective date of January 1, 1863, it had minimal immediate effect on most slaves’ day-to-day lives, particularly in Texas. Texas was resistant to the Emancipation Proclamation, and though slavery was very prevalent in East Texas, it was not as common in the Western areas of Texas, particularly the Hill Country, where most German-Americans were opposed to the practice. Juneteenth commemorates June 18 and 19, 1865. June 18 is the day Union General Gordon Granger and 2,000 federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take possession of the state and enforce the emancipation of its slaves. On June 19, 1865, legend has it while standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger read the contents of “General Order No. 3”:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.[9]

That day has since become known as Juneteenth, a name derived from a portmanteau of the words June and nineteenth.

Former slaves in Galveston rejoiced in the streets with jubilant celebrations. Juneteenth celebrations began in Texas the following year.[9] Across many parts of Texas, freed people pooled their funds to purchase land specifically for their communities’ increasingly large Juneteenth gatherings — including Houston’s Emancipation Park, Mexia’s Booker T. Washington Park, and Emancipation Park in Austin.[9]

In literature

Ralph Ellison's second novel Juneteenth deals with this holiday and its traditions. Juneteenth was published posthumously.

Carolyn Meyer's novel Jubilee Journey is the story of one young biracial girl celebrating Juneteenth with her relatives in Texas, while also learning to be proud of her African American heritage.

Ann Rinaldi's historical novel Come Juneteenth is the story of how Juneteenth came to be, and follows the life of a young white plantation-owner's daughter in Texas during the Civil War whose family faces tragedy after their mulatto half-sister runs away when learning they lied to her about being free.

Traditions

Traditions include an enunciated public reading of the Emancipation Proclamation as a reminder that the slaves have been proclaimed free. The events are celebratory and festive. Many African American families use this opportunity to retrace their ancestry to the ancestors who were held in bondage for centuries, exchange artifacts, debunk family myths, and stress responsibility and striving to be the best you can be.[10] Celebrants often sing traditional songs as well such as Swing Low, Sweet Chariot; Lift Every Voice and Sing; and poetry from Black authors like Maya Angelou.[11] Juneteenth celebrations also include a wide range of festivities to celebrate American heritage, such as parades, rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, or park parties that include such things as African American music and dancing or contests of physical strength and intellect. Some of the events may include black cowboys, historical reenactments, or Miss Juneteenth contests. Traditional American sports may also be played such as baseball, football, or basketball tournaments.[10]

Juneteenth's decline and resurgence

Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States and has been an African American tradition since the late 19th century.[12] Economic and cultural forces caused a decline in Juneteenth celebrations beginning in the early 20th century. The Depression forced many blacks off of farms and into the cities to find work. In these urban environments, employers were less eager to grant leaves to celebrate this date. July 4 was the already established Independence Day holiday, and a rise in patriotism among black Americans steered more toward this celebration.

The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s yielded both positive and negative results for the Juneteenth celebrations. While it pulled many of the African American youth away and into the struggle for racial equality, many linked these struggles to the historical struggles of their ancestors.[12]

Again in 1968, Juneteenth received another strong resurgence through Poor Peoples March to Washington D.C. Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s call for people of all races, creeds, economic levels and professions to come to Washington to show support for the poor. Many of these attendees returned home and initiated Juneteenth celebrations in areas previously absent of such activity. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s Juneteenth continued to enjoy a growing interest from communities and organizations throughout the country as African Americans have an interest to see that the events of 1865 in Texas are not forgotten. Many see roots tying back to Texas soil from which all remaining American slaves were finally granted their freedom.[12]

Most recently in 1994, the era of the "Modern Juneteenth Movement" began when a group of Juneteenth leaders from across the country gathered in New Orleans, Louisiana, at Christian Unity Baptist Church to work for greater national recognition of Juneteenth. The meeting was convened by Rev. John Mosley, director of the New Orleans Juneteenth Freedom Celebration.[citation needed]

Several national Juneteenth organizations were ignited from this gathering beginning with the National Association of Juneteenth Lineage (NAJL), followed by the National Juneteenth Celebration Association (NJCA), the National Juneteenth Christian Leadership Council (NJCLC), and the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation (NJOF). Shortly before this gathering, Juneteenth America, Inc. (JAI) was founded by John Thompson, who organized the first National Juneteenth Convention & Expo, and the National Juneteenth Celebraton Foundation (NJCF) founded by Ben Haith, the creator of the National Juneteenth Flag.[citation needed] In 1997, through the leadership of Lula Briggs Galloway, president of the NAJL, and Rev. Ronald V. Myers, Sr., chairman of the NAJL, the U.S. Congress officially passed historic legislation recognizing Juneteenth as "Juneteenth Independence Day" in America.[citation needed]

This article reads like a press release or a news article and may be largely based on routine coverage. (June 2010) |

Rev. Myers returned to Washington, D.C., in 2000, as founder and chairman of the NJOF, to establish the annual Washington Juneteenth National Holiday Observance and to begin the campaign to establish Juneteenth Independence Day as a National Day of Observance and an official state holiday or state holiday observance in all 50 states and U.S. territories. As of 2010, 35 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation to officially recognize Juneteenth.[13] The annual Congressional Juneteenth Reception, hosted by members of Congress at the U.S. Capitol, was established as a part of the Washington Juneteenth National Holiday Observance.[citation needed]

Myers established the annual National Day of Reconciliation and Healing from the Legacy of Enslavement and the National Juneteenth Black Holocaust "Maafa" Memorial Service as a part of the Washington Juneteenth National Holiday Observance.[citation needed] On the "19th of June," 2000, Myers stood with Congressman Tony Hall (D-OH) as historic Apology for Slavery legislation was announced at the U.S. Capitol during the First National Day of Reconciliation & Healing From the Legacy of Enslavement.[citation needed]

As the National Juneteenth Jazz Artist, Myers also established "June Is Black Music Month!" Celebrating Juneteenth Jazz, "Preserving Our African American Jazz Legacy!" with a series of Juneteenth jazz heritage and arts festivals, concerts, jam sessions, and lectures throughout the country.[citation needed] Myers is also the leader of the National Juneteenth Holiday Campaign, which is working to pass legislation in the U.S. Congress to make Juneteenth Independence Day a National Day of Observance.[citation needed]

See also

- Slavery in the United States

- Emancipation Day

- African American

- 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution - not ratified by Texas until February 18, 1870.

References

- ^ a b c d "Vermont adopts Juneteenth". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ a b "Kansas Becomes the 31st State to Recognize Juneteenth as a State Holiday". National Juneteenth Observance Foundation. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ^ "Official Holidays of the State of Texas". State of Texas website. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

- ^ "The World Celebrates Freedom". Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e f Moskin, Julie (2004-06-18). "An Obscure Texas Celebration Makes Its Way Across the U.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- ^ "Juneteenth Freedom Day". Retrieved 15 January 2009.

...I, Jennifer M. Granholm, Governor of the State of Michigan, do hereby proclaim June 19, 2008, as Juneteenth Freedom Day in Michigan, and I encourage all citizens to reflect upon the value of freedom.

- ^ "10.55, 2009 Minnesota Statutes". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ http://www.juneteenth.com/

- ^ a b c "Juneteenth". State of Texas website. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

- ^ a b http://www.juneteenth.com/howtocelebrate.htm

- ^ Taylor, 2002. pp. 28-29.

- ^ a b c http://www.juneteenth.com/history.htm

- ^ http://www.juneteenth.us

External links

- Juneteenth History

- National Juneteenth Observance Foundation

- Juneteenth World Wide Celebration

- National Juneteenth Holiday Campaign

- National Juneteenth Christian Leadership Council

- Animated Printable Juneteenth Card by Kenneth Burton

- 19th of June

- Juneteenth in the Classroom

- Juneteenth from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Texas State Library’s Juneteenth page

- Festival for Charlotte, NC and surrounding area

- Juneteenth America, Inc.--California Juneteenth

- Rappahannock Regional Juneteenth Celebration

- Juneteenth New Jersey Celebration

- Juneteenth Maryland Celebration

- Pennsylvania Juneteenth Coalition

- Massachusetts to 'recognize' Juneteenth Boston Globe

- Rappahannock Regional Juneteenth Celebration

- Sioux City Juneteenth Celebration

- Iowa Juneteenth Observance

- Juneteen Organization of Pueblo, Colorado