Grizzly bear: Difference between revisions

Pinethicket (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 69.56.69.231 (talk) to last version by Brian Crawford |

→Conflicts with humans: Correct "home in" to "hone in" |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

Grizzly bears normally avoid contact with people. In spite of their obvious physical advantages and many opportunities, they almost never view humans as prey; bears rarely actively hunt humans.<ref>Ministry of Environment. 2002. Grizzly Bears in British Columbia. Retrieved on Oct. 12, 2009 from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/grzzlybear.pdf</ref> Most grizzly bear attacks result from a bear that has been surprised at very close range, especially if it has a supply of food to protect, or female grizzlies protecting their offspring. In such situations, property may be damaged and the bear may physically harm the person.<ref name="MacHutcheon">{{Citation |last=MacHutchon |first=A. Grant |lastauthoramp=yes |first2=Debbie W. |last2=Wellwood |year=2002 |title=Reducing bear-human conflict through river recreation management |journal=Ursus |volume=13 |issue= |pages=357–360 |doi= |url=http://jstor.org/stable/3873216 }}.</ref> |

Grizzly bears normally avoid contact with people. In spite of their obvious physical advantages and many opportunities, they almost never view humans as prey; bears rarely actively hunt humans.<ref>Ministry of Environment. 2002. Grizzly Bears in British Columbia. Retrieved on Oct. 12, 2009 from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/grzzlybear.pdf</ref> Most grizzly bear attacks result from a bear that has been surprised at very close range, especially if it has a supply of food to protect, or female grizzlies protecting their offspring. In such situations, property may be damaged and the bear may physically harm the person.<ref name="MacHutcheon">{{Citation |last=MacHutchon |first=A. Grant |lastauthoramp=yes |first2=Debbie W. |last2=Wellwood |year=2002 |title=Reducing bear-human conflict through river recreation management |journal=Ursus |volume=13 |issue= |pages=357–360 |doi= |url=http://jstor.org/stable/3873216 }}.</ref> |

||

Exacerbating this is the fact that intensive human use of grizzly habitat coincides with the seasonal movement of grizzly bears.<ref name="MacHutcheon"/> An example of this temporal/spatial conflict occurs during the fall season: grizzly bears congregate near streams to feed on salmon when anglers are also intensively using the river. Some grizzly bears appear to have learned to |

Exacerbating this is the fact that intensive human use of grizzly habitat coincides with the seasonal movement of grizzly bears.<ref name="MacHutcheon"/> An example of this temporal/spatial conflict occurs during the fall season: grizzly bears congregate near streams to feed on salmon when anglers are also intensively using the river. Some grizzly bears appear to have learned to hone in on the sound of hunters' gunshots in late fall as a source of potential food, and inattentive hunters have been attacked by bears trying to appropriate their kills.{{Citation needed|date=April 2009}} |

||

Increased human-bear interaction has created ‘problem bears’, which are bears that have become adapted to human activities or habitat.<ref name="AustinWrenshall">Austin, M. A., Wrenshall, C. 2004. An Analysis of Reported Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos): Mortality Data for British Columbia from 1978–2003. BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. Retrieved on Oct. 27, 2009 from http://www.elp.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/gb_mortality_analysis.pdf</ref> Aversive conditioning, a method involving using deterrents such as rubber bullets, foul-tasting chemicals or acoustic devices to teach bears to associate humans with negative experiences, is ineffectual when bears have already learned to positively associate humans with food.<ref name="CiarnielloDavis"/> Such bears are translocated or killed because they pose a threat to humans. The B.C. government kills approximately 50 problem bears each year<ref name="CiarnielloDavis"/> and overall spends more than one million dollars annually to address bear complaints, relocate bears and kill them.<ref name="CiarnielloDavis">{{Citation |last=Ciarniello |first=L. |last2=Davis |first2=H. |lastauthoramp=yes |last3=Wellwood |first3=D. |year=2002 |title=“Bear Smart” Community Program Background Report |publisher=BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection |accessdate=October 30, 2009 |url=http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/bearsmart_bkgdr.pdf }}.</ref> |

Increased human-bear interaction has created ‘problem bears’, which are bears that have become adapted to human activities or habitat.<ref name="AustinWrenshall">Austin, M. A., Wrenshall, C. 2004. An Analysis of Reported Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos): Mortality Data for British Columbia from 1978–2003. BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. Retrieved on Oct. 27, 2009 from http://www.elp.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/gb_mortality_analysis.pdf</ref> Aversive conditioning, a method involving using deterrents such as rubber bullets, foul-tasting chemicals or acoustic devices to teach bears to associate humans with negative experiences, is ineffectual when bears have already learned to positively associate humans with food.<ref name="CiarnielloDavis"/> Such bears are translocated or killed because they pose a threat to humans. The B.C. government kills approximately 50 problem bears each year<ref name="CiarnielloDavis"/> and overall spends more than one million dollars annually to address bear complaints, relocate bears and kill them.<ref name="CiarnielloDavis">{{Citation |last=Ciarniello |first=L. |last2=Davis |first2=H. |lastauthoramp=yes |last3=Wellwood |first3=D. |year=2002 |title=“Bear Smart” Community Program Background Report |publisher=BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection |accessdate=October 30, 2009 |url=http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/bearsmart_bkgdr.pdf }}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:48, 19 September 2010

| Grizzly bear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | U. a. horribilis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Ursus arctos horribilis (Ord, 1815)

| |

| |

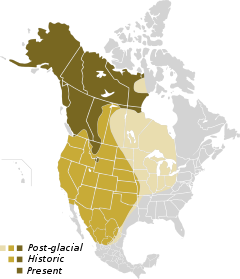

| Shrinking distribution during post-glacial, historic and present time | |

The grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis), also known as the silvertip bear, is a subspecies of brown bear (Ursus arctos) that generally lives in the uplands of western North America. This subspecies is thought to descend from Ussuri brown bears which crossed to Alaska from Eastern Russia 100,000 years ago, though they did not move south until 13,000 years ago.[1]

Grizzlies are normally solitary active animals, but in coastal areas the grizzly congregates alongside streams, lakes, rivers, and ponds during the salmon spawn. Every other year, females (sows) produce one to four young (commonly two) which are small and weigh only about 500 grams (one pound). A sow is protective of her offspring and will attack if she thinks she or her cubs are threatened.

Description

Grizzly bears are North America’s second largest land carnivore, after the polar bear.[2] Size and weight varies greatly according to geographic location. Inland bears, particularly those of the Yukon region, may weigh as little as 135 kg (298 lb) for adult males. The largest populations are found in coastal areas where weights are as much as 550 kg (1,210 lb). Populations found in Katmai National Park and the Alaskan Peninsula may approach or just exceed 680 kg (1,500 lb). The females are on average 38% smaller,[3] at about 115–160 kg (254–353 lb),[4] an example of sexual dimorphism. On average, grizzly bears stand about 1 metre (3.3 feet) at the shoulder when on all fours and 2 metres (6.6 feet) on their hind legs,[5] but males often stand 2.4 metres (7.9 feet) or more on their hind legs. On average, grizzly bears from the Yukon River area are about 20% smaller than typical grizzlies.[6] Formerly, taxonomists listed brown and grizzly bears as separate species. The grizzly is classified as a brown bear subspecies, Ursus arctos horribilis. The term “brown bear” is commonly used to refer to the members of this subspecies found in coastal areas where salmon is the primary food source, but in fact, these are just coastal grizzlies in contemporary taxonomic classification. Inland bears and those found in northern habitats are more often called “grizzlies.” Brown bears on Kodiak Island (referred to as Kodiak bears) are classified as a distinct subspecies from those on the mainland because they are genetically and physically isolated. The shape of their skulls also differs slightly.

The grizzly's coloring ranges widely depending on geographic areas, from white to almost black, and all shades in between.[2] The grizzly also has a large hump over the shoulders, which is a muscle mass used to power the forelimbs in digging. This muscle is commonly used to dig for their various vegetative food sources.[7] The hind legs are more powerful, however. The muscles in the lower legs provide enough strength for the bear to stand up and even walk short distances on its hind legs, giving it a better view of its surroundings. The head is large and round with a concave, disk-shaped, facial profile. In spite of their massive size, these bears can run at speeds of up to 55 kilometres per hour (34 miles per hour). However, they are slower running downhill than uphill because of the large hump of muscle over the shoulders. They have very thick fur to keep them warm in brutal, windy, and snowy winters.

Grizzlies can be distinguished from most other brown bear subspecies by their proportionately longer claws and cranial profile, which resembles that of the polar bear.[8] Compared to other North American brown bear subspecies, a grizzly has a silver-tipped pelt and is smaller in size. This size difference is due to the lesser availability of food in the grizzlies' landlocked habitats.[9] They are similar in size, color and behaviour to the Siberian brown bear (Ursus arctos collaris). Grizzly bears also characteristically have claws that are twice the length of their toes.[2][10]

Name

The word "grizzly" in its name refers to "grizzled" or grey hairs in its fur, but when naturalist George Ord formally named the bear in 1815, he misunderstood the word as "grisly", to produce its biological Latin specific or subspecific name "horribilis".[11]

Range

Grizzly bears are found in Asia, Europe and North America, giving them one of the widest ranges compared to other bear species. The grizzly bear originated in Eurasia and traveled to North America approximately 50,000 years ago.[12] This is a very recent event in evolutionary time, causing the North American grizzly bear to be very similar to the brown bears inhabiting Europe and Asia. In North America, grizzly bears previously ranged from Alaska to Mexico and as far east as the Hudson Bay area.[12] In North America, the species is now found only in Alaska, south through much of western Canada, and into portions of the northwestern United States including Idaho, Montana, Washington and Wyoming, extending as far south as Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, but is most commonly found in Canada. There may still be a small population in Colorado in the southern San Juan Mountains. In September 2007 a hunter produced evidence of grizzly bear rehabilitation in the Selway-Bitterroot ecosystem, in Idaho and western Montana, by killing a male grizzly bear.[13] Its original range also included much of the Great Plains and the southwestern states, but it has been extirpated in most of those areas. The grizzly bear also appears on the Flag of California, though they are extinct in the state, the last one having been shot in 1922.[14] Excluding Alaska, the United States has fewer than 1000 grizzly bears.[12] In Canada there are approximately 25,000 grizzly bears occupying British Columbia, Alberta, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and the northern part of Manitoba.[12] Combining Canada and the United States, grizzly bears inhabit approximately half the area of their historical range.[12] In British Columbia, grizzly bears inhabit approximately 90% of their original territory. There were approximately 25,000 grizzly bears in British Columbia when the European settlers arrived.[12] However, population size significantly decreased due to hunting and habitat loss. In 2008 it was estimated that there were 16,014 grizzly bears. Population estimates for British Columbia are based on Hair-Snagging, DNA-based inventories, Mark-Recapture and a refined Multiple Regression model.[15] Other provinces and the United States may use a combination of different methods for population estimates. Therefore it is difficult to say precisely what methods were used to produce total population estimates for Canada and North America as they were likely developed from a variety of different studies. The grizzly bear currently has legal protection in Mexico, European countries, some areas of Canada and in the United States. However, it is expected that the re-population of its former range will be a slow process, due equally to the ramifications of reintroducing such a large animal to areas which are prized for agriculture and livestock and also to the bear's slow reproductive habits (bears invest a good deal of time in raising young). There are currently about 55,000 wild grizzly bears located throughout North America.[12]

Brown bears (of which the grizzly bear is a subspecies) can live up to thirty years in the wild, though twenty to twenty-five is normal.[16]

Reproduction

Grizzly bears have one of the lowest reproductive rates of all terrestrial mammals in North America.[17] This is due to numerous ecological factors. Grizzly bears do not reach sexual maturity until they are at least five years old.[12][18] Once mated with a male in the summer, the female delays embryo implantation until hibernation, during which abortion can occur if the female does not receive the proper nutrients and caloric intake.[19] On average, females produce two cubs in a litter[18] and the mother cares for the cubs for up to two years, during which the mother will not mate.[12] Once the young leave or are killed, females may not produce another litter for three or more years depending on environmental conditions.[20] Male grizzly bears have large territories, up to 4,000 square kilometres (1,500 square miles),[17] making finding a female scent difficult in such low population densities.

Grizzlies are subject to fragmentation, a form of population segregation.[21] Fragmentation causes inbreeding depression, which leads to a decrease in genetic variability in the grizzly bear species.[22] This decreases the fitness of the population for several reasons. First, inbreeding forces competition with relatives, which decreases the evolutionary fitness of the species.[22] Secondly, the decrease in genetic variability causes an increased possibility that a lethal homozygous recessive trait may be expressed; this decreases the average litter size reproduced, indirectly decreasing the population.[23]

Diet

Although grizzlies are of the order Carnivora and have the digestive system of carnivores, they are actually omnivores, since their diet consists of both plants and animals. They have been known to prey on large mammals, when available, such as moose, deer, sheep, elk, bison, caribou and even black bears. Grizzly bears feed on fish such as salmon, trout, and bass, and those with access to a more protein-enriched diet in coastal areas potentially grow larger than interior individuals. Grizzly bears also readily scavenge food, on carrion left behind by other animals.[24]

The grizzly bears that reside in the American Rocky Mountains are not as large as Canadian or Alaskan grizzlies. This is due, in part, to the richness of their diet, which in Yellowstone consists mostly of whitebark pine nuts, as well as roots, tubers, grasses, various rodents, army cutworm moths and scavenged carcasses. None of these, however, match the fat content of the salmon available in Alaska and British Columbia.

Plants make up approximately 80%–90% of a grizzly bears’ diet. Various berries make up a large portion of this. These can include blueberries (Vaccinium cyanococcus), blackberries (Rubus fruticosus), salmon berries (Rubus spectabilis), cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccus), buffalo berries (Shepherdia argentea), and huckleberries (Vaccinium parvifolium), depending on the environment. Insects such as ladybugs, ants and bees are also eaten, but only if they are available in large quantities. At low quantities, the energy gained is not worth the foraging energy output.[2] When food is abundant, grizzly bears will feed in groups, foraging together. For example, many grizzly bears will visit meadows right after there has been an avalanche or glacier slide. This is due to an influx of legumes, such as Hedysarum, which the grizzlies consume in massive amounts.[7] When food sources become scarcer, however, they separate once again.

In preparation for winter, bears can gain approximately 400 lb (180 kg), during a period of hyperphagia, before going into a state of false hibernation. The bear often waits for a substantial snowstorm before it enters its den, such behaviour lessening the chances that predators will be able to locate the den. The dens themselves are typically located at elevations above 6,000 feet on northern-facing slopes. There is some debate amongst professionals as to whether grizzly bears technically hibernate. Much of the debate revolves around body temperature and the ability of the bears to move around during hibernation on occasion. Grizzly bears have the ability to "partially" recycle their body wastes during this period. In some areas where food is plentiful year round, grizzly bears skip hibernation altogether.[citation needed]

Interspecific competition

Most notable in Yellowstone have been the interactions between gray wolves and grizzly bears. Since the reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone, many visitors have witnessed a once common struggle between a keystone species, the grizzly bear, and its historic rival, the grey wolf. The interactions of U. arctos horribilis with the wolves of Yellowstone have been under considerable study. Typically, the conflict will be in the defense of young or over a carcass, which is commonly an elk killed by wolves.[25] The grizzly bear uses its keen sense of smell to locate the kill. Then the wolves and grizzly will play a game of cat and mouse. One wolf may try to distract the bear while the others feed. The bear then may retaliate by chasing the wolves. If the wolves become aggressive with the bear it is normally in the form of quick nips at its hind legs. Thus, the bear will sit down and use its ability to protect itself in a full circle. Rarely do interactions such as these end in death or serious injury to either animal. One carcass simply isn't usually worth the risk to the wolves (if the bear has the upper hand due to strength and size) or to the bear (if the wolves are too numerous or persistent).

Black bears generally stay out of grizzly territory but grizzlies may occasionally enter their terrain to obtain food sources both bears enjoy, such as pine nuts, acorns, mushrooms, and berries. When a black bear sees a grizzly coming it either turns tail and runs or climbs a tree. Black bears are not strong competition for prey because they have a more herbivorous diet. Confrontations are rare because of the difference in size, habitat, and diet of the bear species. When this happens it is usually with the grizzly being the aggressor. The black bear will only fight when it is a smaller grizzly such as a yearling or when the black bear has no other choice but to defend itself.

The segregation of black bear and grizzly bear populations is possibly due to competitive exclusion. In certain areas grizzly bears out compete black bears for the same resources.[26] For example, many Pacific coastal islands off of British Columbia and Alaska support either the black bear or the grizzly, but rarely both.[27] In regions where both species coexist, they are divided by landscape gradients such as age of forest, elevation and openness of land. Grizzly bears tend to favor old forests with high productivity, higher elevations and more open habitats compared with black bears.[26]

The relationship between grizzly bears and other predators is mostly one-sided; grizzly bears will approach feeding predators to steal their kill. In general, the other species will leave the carcasses for the bear to avoid competition or predation. Any parts of the carcass left uneaten are scavenged by smaller animals.[20]

Polar bears do not often come in contact with grizzlies due to different habitats and diets. However when they do meet, the grizzly is the aggressor, often driving the polar bears off.[citation needed] This is partly because grizzlies are territorial and Polar Bears are not.[citation needed] Cougars, however, generally give the bears a wide berth. Grizzlies have less competition with cougars than with other predators such as coyotes, wolves, and other bears. When a grizzly descends on a cougar feeding on its kill, the cougar usually gives way to the bear. When a cougar does stand its ground, the cougar will use its superior agility and its claws to harass the bear yet stay out of its reach until one of them gives up.

Coyotes, foxes, and wolverines are generally regarded as pests to the grizzlies rather than competition, though coyotes and wolverines may compete for smaller prey such as rabbits and deer. All three will try to scavenge whatever they can from the bears. Wolverines are aggressive enough to occasionally persist until the bear finishes to eat, leaving more than normal scraps for the smaller animal.[citation needed]

Ecological role

The grizzly bear has several relationships with its ecosystem. One such relationship is a mutualistic relationship with fleshy-fruit bearing plants. After the grizzly consumes the fruit, the seeds are dispersed and excreted in a germinable condition. Some studies have shown that germination success is indeed increased as a result of seeds being deposited along with nutrients in feces.[28] This makes the grizzly bear an important seed distributor in their habitat.[29]

While foraging for tree roots, plant bulbs, or ground squirrels, bears stir up the soil. This process not only helps grizzlies access their food, but it also increases species richness in alpine ecosystems.[30] An area that contains both bear digs and undisturbed land has greater plant diversity than an area that contains just undisturbed land.[30] Along with increasing species richness, soil disturbance causes nitrogen to be dug up from lower soil layers, and makes nitrogen more readily available in the environment.[31] An area that has been dug by the grizzly bear has significantly more nitrogen than an undisturbed area.

Nitrogen cycling is not only facilitated by grizzlies digging for food, it is also accomplished via their habit of carrying salmon carcasses into surrounding forests.[32] It has been found that spruce tree (Picea glauca) foliage within 500 m (1,600 ft) of the stream where the salmon have been obtained, contains nitrogen originating from salmon the bears have preyed on.[33] These nitrogen influxes to the forest are directly related to the presence of grizzly bears and salmon.[34]

Grizzlies directly regulate prey populations, and also help prevent overgrazing in forests by controlling the populations of other species in the food chain.[35] An experiment in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, USA, showed that removal of wolves and grizzly bears caused populations of their herbivorous prey to increase.[36] This in turn changed the structure and density of plants in the area, which decreased the population sizes of migratory birds.[36] This provides evidence that grizzly bears represent a keystone predator, having a major influence on the entire ecosytem they inhabit.[35]

Conflicts with humans

Grizzlies are considered by some experts to be the most aggressive bears[citation needed] even by the standards of brown bears.[37] Aggressive behavior in grizzly bears is favored by numerous selection variables. Unlike the smaller black bears, adult grizzlies are too large to escape danger by climbing trees, so they respond to danger by standing their ground and warding off their attackers. Increased aggressiveness also assists female grizzlies in better ensuring the survival of their young to reproductive age.[38] Mothers defending cubs are the most prone to attacking, being responsible for 70% of fatal injuries to humans.[39] Historically, bears have competed with other large predators for food, which also favors increased aggression.

Grizzly bears normally avoid contact with people. In spite of their obvious physical advantages and many opportunities, they almost never view humans as prey; bears rarely actively hunt humans.[40] Most grizzly bear attacks result from a bear that has been surprised at very close range, especially if it has a supply of food to protect, or female grizzlies protecting their offspring. In such situations, property may be damaged and the bear may physically harm the person.[41]

Exacerbating this is the fact that intensive human use of grizzly habitat coincides with the seasonal movement of grizzly bears.[41] An example of this temporal/spatial conflict occurs during the fall season: grizzly bears congregate near streams to feed on salmon when anglers are also intensively using the river. Some grizzly bears appear to have learned to hone in on the sound of hunters' gunshots in late fall as a source of potential food, and inattentive hunters have been attacked by bears trying to appropriate their kills.[citation needed]

Increased human-bear interaction has created ‘problem bears’, which are bears that have become adapted to human activities or habitat.[42] Aversive conditioning, a method involving using deterrents such as rubber bullets, foul-tasting chemicals or acoustic devices to teach bears to associate humans with negative experiences, is ineffectual when bears have already learned to positively associate humans with food.[43] Such bears are translocated or killed because they pose a threat to humans. The B.C. government kills approximately 50 problem bears each year[43] and overall spends more than one million dollars annually to address bear complaints, relocate bears and kill them.[43]

It is imperative for all campers in areas inhabited by grizzly to maintain a clean campsite. Even oil from food cooked outdoors can attract a bear.[42] Reports have indicated that something as innocuous as a tube of lip balm can entice a bear to come near a campsite in search of food. A bear accustomed to finding food around campsites will usually return to those sites. Park rangers may at this time decide that the bear has become a threat to campers, and kill it. For back-country campers, hanging food between trees at a height unreachable to bears is a common procedure, although some grizzlies can climb and reach hanging food in other ways. An alternative to hanging food is to use a bear canister.[44]

Traveling in groups of six or more can significantly reduce the chance of bear-related injuries while hiking in bear country.[45]

Legal status

The grizzly bear is listed as threatened in the contiguous United States and endangered in parts of Canada. In May 2002, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the Prairie population (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba range) of grizzly bears as being wiped out in Canada.[46] In Alaska and parts of Canada however, the grizzly is still legally shot for sport by hunters. On January 9, 2006, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to remove Yellowstone grizzlies from the list of threatened and protected species.[47] In March 2007, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service "de-listed" the population,[48] effectively removing Endangered Species Act protections for grizzlies in the Yellowstone National Park area. On September 22, 2009, a federal judge reinstated protection for the bears[49]

Protection

Within the United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concentrates its effort to restore grizzly bears in six recovery areas. These are Northern Continental Divide (Montana), Yellowstone (Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho), Cabinet-Yaak (Montana and Idaho), Selway-Bitterroot (Montana and Idaho), Selkirk (Idaho and Washington), and North Cascades (Washington). The grizzly population in these areas is estimated at 750 in the Northern Continental Divide, 550 in Yellowstone, 40 in the Yaak portion of the Cabinet-Yaak, and 15 in the Cabinet portion (in northwestern Montana), 105 in Selkirk region of Idaho, 10–20 in the North Cascades, and none currently in Selway-Bitterroots, although there have been sightings[50] These are estimates because bears move in and out of these areas, and it is therefore impossible to conduct a precise count. In the recovery areas that adjoin Canada, bears also move back and forth across the international boundary.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service claims that the Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk areas are linked through British Columbia, a claim that is disputed.[51]

All national parks, such as Banff National Park, Yellowstone and Grand Teton, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park have laws and regulations in place to protect the bears. Even so, grizzlies are not always safe in parks. In Glacier National Park in Montana and Banff National Park in Alberta, grizzlies are regularly killed by trains as the bears scavenge for grain that has leaked from poorly maintained grain cars. Road kills on park roads are another problem. The primary limiting factors for grizzly bears in Alberta and elsewhere are human-caused mortality, unmitigated road access, and habitat loss, alienation, and fragmentation. In the Central Rocky Mountains Ecosystem, most bears have died within a few hundred meters of roads and trails.[52]

On March 22, 2007, the U.S. government stated that grizzly bears in and around Yellowstone National Park (Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem) no longer need Endangered Species Act protection. Several environmental organizations, including the NRDC, have since brought a lawsuit against the federal government to re-list the grizzly bear. On September 22, 2009, United States District Judge Donald W. Molloy reinstated the grizzlies' protected status due to the decline of whitebark pine tree, whose nuts are a main source of food for the bears.[49]

Farther north, in Alberta, Canada, intense DNA hair-snagging studies on 2000 showed the grizzly population to be increasing faster than what it was formerly believed to be, and Alberta Sustainable Resource Development calculated a population of 841 bears.[52] In 2002, the Endangered Species Conservation Committee recommended that the Alberta grizzly bear population be designated as Threatened due to recent estimates of grizzly bear mortality rates that indicated that the population was in decline. A recovery plan released by the Provincial government in March 2008 indicates that the grizzly population is lower than previously believed.[53] The Provincial government has so far resisted efforts to designate its declining population of about 700 grizzlies (previously estimated at as high as 842) as endangered.[citation needed]

Environment Canada consider the Grizzly bear to a "special concern" species, as it is particularly sensitive to human activities and natural threats. In Alberta and British Columbia, the species is considered to be at risk.[54]

Recently the International Union for Conservation of Nature moved the Grizzly bear to "Lower Risk Least Concern" status on the IUCN Red List.[55][56]

The Mexican Grizzly Bear is extinct.[57]

Conservation efforts

In 2008 it was estimated that there were 16,014 grizzly bears in the British Columbia population.[58] As of 2002 Grizzly Bears were listed as Special Concern under the COSEWIC registry[59] and considered threatened under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[60] Conservation efforts have become an increasingly vital investment over recent decades as population numbers have dramatically declined. Establishment of Parks and protected areas are one of the main focuses currently being tackled to help reestablish the low grizzly bear population in British Columbia. One example of these efforts is The Khutzeymateen Grizzly Sanctuary located along the north coast of British Columbia and 44,300 hectares in size, composed of key habitat for this threatened species. Regulations such as limited public access as well as a strict no hunting policy have enabled this location to be a safe haven for local Grizzlies in the area.[61] When choosing the location of a park focused on grizzly bear conservation, factors such as habitat quality and connectivity to other habitat patches must be considered. To maximize protection for grizzly bears in protected areas, regulations should also be put in place once the park is created. These generally include a ban on hunting and limited human visitation and access.

The Refuge for Endangered Wildlife located on Grouse Mountain in Vancouver is an example of a different type of conservation effort for the diminishing Grizzly Bear population. The refuge is a five-acre terrain which has functioned as a home for two orphaned Grizzly Bears since 2001.[62] The purpose of this refuge is to provide awareness and education to the public surrounding Grizzly Bears, as well as providing an area for research and observation of this secluded species.

Another factor currently being taken into consideration when designing conservation plans for future generations are anthropogenic barriers in the form of urban development and roads. These elements are acting as obstacles causing fragmentation of the remaining grizzly bear population habitat and prevention of gene flow between subpopulations (For example: in Banff National Park). This in turn is creating a decline in genetic diversity, and therefore the overall fitness of the general population is lowered.[23] In light of these issues conservation plans often include migration corridors by way of long strips of “park forest” to connect less developed areas, or by way of tunnels and overpasses over busy roads.[63] Using GPS collar tracking scientists can study whether or not these efforts are actually making a positive contribution towards resolving the problem.[64] To date it has been found that most corridors are infrequently used and thus genetic isolation is currently occurring, which can result in inbreeding and therefore an increased frequency of deleterious genes through genetic drift.[65] Current data suggests that female grizzly bears are disproportionately less likely than males to use these corridors, which can prevent mate access and decrease the number of offspring.

Hunting

Trophy hunting causes an imbalance between the male and female sexes, since older males are primarily sought to be hunted for their size.[35] The hunting of older males creates a gender imbalance within an area specific population.[66] The killing of older male bears in their own territory allows other males to migrate in and claim the late bear's territory. Older male bears will have had cubs with existing female bears in the region. This may cause the newly migrated male bear to become potentially infanticidal towards cubs of the resident females and the late male bear.[23] Generally females try to avoid these immigrant males causing a reduction in the female's reproduction rate to approximately three to four cubs per mating season.[35]

See also

- Grizzly-polar bear hybrid

- Grizzly Peak (Berkeley Hills)

- List of fatal bear attacks in North America

- Hunting Status On Grizzly Bears in British Columbia, Canada

Notes

- ^ McLellan, Bruce; Reiner, David C. (1994), "A review of bear evolution" (PDF), Int. Conf. Bear Res. and Manage, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 85–96

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b c d "Grizzly", Hinterland Who's Who, retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Brown, Gary (1996), Great Bear Almanac, p. 340, ISBN 1558214747

- ^ "Grizzly Bear", U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ Cameron, Ward (2005), How do you distinguish a black bear from a grizzly bear.

- ^ The Bear Facts – Types of bears in the Yukon

- ^ a b Derych, John (2001), "Brown / Grizzly Bear Facts", North American Bear Center.

- ^ Hutchinson's animals of all countries; the living animals of the world in picture and story Vol.I, 1923, p. 384

- ^ Brown bear, Grizzly bear or Kodiak bear?

- ^ Brown Bear Hunting in Russia

- ^ Wright, William Henry (1977) [1909], The Grizzly Bear, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, pp. 28–29, ISBN 978-0-8032-5865-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blood, D. A. (2002), Grizzly Bears in British Columbia, Province of British Columbia: Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection.

- ^ "Grizzly shot in Selway-Bitterroot", Missoulian website.

- ^ http://www.library.ca.gov/history/symbols.html

- ^ Hamilton, A.N. 2008 Grizzly Bear Population Estimate for British Columbia. Ministry of Environment, British Columbia

- ^ "Grizzly Bear", Defenders of Wildlife website.

- ^ a b "Trophy Hunting of BC Grizzly Bears", Pacific Wild

- ^ a b MacDonald, Jason; MacDonald, Paula; MacPhee, Mitchell; Nicolle, Paige, "Endangered Wildlife: Grizzly Bear", Edu.pe.ca

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Herrero, Stephen, "Grizzly Bear", The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Assessment and Update Status Report on the Grizzly Bear Ursus arctos in Canada (PDF)

- ^ Proctor, Michael F.; McLellan, Bruce N.; Strobeck, Curtis (2002), "Population Fragmentation of Grizzly Bears in Southeastern British Columbia, Canada", Ursus, 8: 153–160

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Proctor, M. F.; McLellan, B. N.; Strobeck, C.; Barclay, R. M. R. (2005), "Genetic analysis reveals demographic fragmentation of grizzly bears yielding vulnerably small populations", Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272 (1579): 2409–2416, doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3246, PMC 1559960, PMID 16243699

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b c Krebs, C. J. (2009), Ecology: The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance (6th ed.), San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings, ISBN 9780321507433.

- ^ Herrero, Stephen (2002), Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance, Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, ISBN 158574557X.

- ^ Gunther, K. A.; Smith, D. W. (2004), "Interactions between wolves and female grizzly bears with cubs in Yellowstone National Park", Ursus, 15: 232–238, doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2004)015<0232:IBWAFG>2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Apps, C. D.; McLellan, B. N.; Woods, J. G. (2006), "Landscape partitioning and spatial inferences of competition between black and grizzly bears", Ecography, 29: 561–572, doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04564.x

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Mattson, T.; Herrero, D. J.; Merrill, S. (2005), "Are black bears a factor in the restoration of North American grizzly bear populations?", Ursus, 16: 11–30, doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2005)016[0011:ABBAFI]2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Meyer, G.; Witmer, M. (1998), "Influence of Seed Processing by Frugivorous Birds on Germination Success of Three North American Shrubs", American Midland Naturalist, 140 (1): 129–139, doi:10.1674/0003-0031(1998)140[0129:IOSPBF]2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Willson, M.; Gende, S. (2004), "Seed Dispersal by Brown Bears, Ursus arctos, in Southeastern Alaska", Canadian Field-Naturalist, 118 (4): 499–503

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Doak, D.; Loso, M. (2003), "Effects of Grizzly Bear Digging on Alpine Plant Community Structure", Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, 35 (4): 499–503, doi:10.1657/1523-0430(2003)035[0421:EOGBDO]2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Tardiff, S.; Stanford, J. (1998), "Grizzly Bear Digging: Effects on Subalpine Meadow Plants in Relation to Mineral Nitrogen Availabilty", Ecology, 79 (7): 2219–2228, doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2219:GBDEOS]2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Quinn, T.; Carlson, S.; Gende, S.; Rich, H. (2009), "Transportation of Pacific Salmon Carcasses from Streams to Riparian Forests by Bears", Canadian Journal of Zoology—Revue Canadienne de Zoology, 87 (3): 195–203, doi:10.1139/Z09-004

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Hilderbrand, G.; Hanley, T.; Robbins, C.; Schwartz, C. (1999), "Role of Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) in the Flow of Marine Nitrogen into a Terrestrial Ecosystem", Oecologia, 121 (4): 546–550, doi:10.1007/s004420050961

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Helfield, J.; Naiman, R. (2006), "Keystone Interactions: Salmon and Bear in Riparian Forests of Alaska", Ecosystems, 9 (2): 167–180, doi:10.1007/s10021-004-0063-5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b c d Peek, J.; Beecham, J.; Garshelis, D.; Messier, F.; Miller, S.; Dale, S. (2003), Management of Grizzly Bears in British Columbia: A Review by and Independent Scientific Panel (PDF), retrieved October 28, 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Berger, J.; Stacey, P.; Bellis, L.; Johnson, M. (2001), "A Mammalian Predator-Prey Imbalance: Grizzly Bear and Wolf Extinction Affect Avian Neo-Tropical Migrants", Ecological Applications, 11 (4): 947–960, doi:10.2307/3061004

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Inter-species conflict. Which animal is the ultimate carnivore?

- ^ Why are grizzly bears more aggressive than our black bears?

- ^ How Dangerous are Black Bears

- ^ Ministry of Environment. 2002. Grizzly Bears in British Columbia. Retrieved on Oct. 12, 2009 from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/grzzlybear.pdf

- ^ a b MacHutchon, A. Grant; Wellwood, Debbie W. (2002), "Reducing bear-human conflict through river recreation management", Ursus, 13: 357–360

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Austin, M. A., Wrenshall, C. 2004. An Analysis of Reported Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos): Mortality Data for British Columbia from 1978–2003. BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. Retrieved on Oct. 27, 2009 from http://www.elp.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/gb_mortality_analysis.pdf

- ^ a b c Ciarniello, L.; Davis, H.; Wellwood, D. (2002), “Bear Smart” Community Program Background Report (PDF), BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, retrieved October 30, 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - ^ Batin, Christopher (January 31, 2006), "How to Outrun a Grizzly [and other really bad ideas]", Outdoor Life

- ^ Herrero, S.; Higgins, A. (2000), "Human Injuries inflicted by bears in Alberta: 1960–98", Ursus, 14 (1): 44–54.

- ^ "Species at Risk – Grizzly Bear Prairie population". Environment Canada. 2006-05-08. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Public Meetings for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Proposal to Remove Yellowstone Area Population of Grizzly Bears from List of Threatened and Endangered Wildlife", U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, December 29, 2005.

- ^ "Successful Recovery Efforts bring Yellowstone Grizzly Bears off the Endangered List" (PDF), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ^ a b Barnett, Lindsay (September 22, 2009), "Judge renews protected status for Yellowstone's grizzly bears", Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Knibb, David, Grizzly Wars: The Public Fight Over the Great Bear pp. 164–213 (Eastern Washington University Press 2008). ISBN 978-1-59766-037-2.

- ^ Knibb, David, Grizzly Wars: The Public Fight Over the Great Bear pp. 202–04 (Eastern Washington University Press 2008). ISBN 978-1-59766-037-2.

- ^ a b "Wildlife Status – Grizzly bear – Population size and trends". Fish and Wildlife Division of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- ^ Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Team. "Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan 2008–2013, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 15" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-06.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 21 (help) - ^ "Species at Risk – Grizzly Bear Northwestern population". Environment Canada. 2006-05-08. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bear Specialist Group 1996. "Ursus arctos. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Retrieved 2008-04-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Huber, Djuro (January 2010). "Ursus arctos (Brown Bear, Grizzly Bear, Mexican Grizzly Bear)". The IUCN red list of endangered species. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Bear Specialist Group 1996. "Ursus arctos ssp. nelsoni. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Retrieved 2008-04-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hamilton, A.N. "Grizzly Bear Population Estimate for British Columbia. In: Ministry of Environment. 2008" (PDF).

- ^ "Species Profile: Grizzly Bear Northwestern Population. In: Species at Risk Public Registry. 2009". Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Grizzly Bear Recovery. In: US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009".

- ^ "Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary. In: BC Parks".

- ^ "Wildlife and Education: Refuge for Endangered Wildlife". Grouse Mountain: The Peak of Vancouver. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Clevenger, A.P.; Waltho, N (2005), "Performance indices to identify attributes of highway crossing structures facilitating movement of large mammals.", Biological Conservation, 121 (121): 453–464, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.04.025.

- ^ Edwards, M.A.; Nagy, J.A.; Derocher, A.E (2008), "Using Subpopulation structure for barren-ground grizzly bear management", Ursus, 19 (2): 91–104, doi:10.2192/1537-6176-19.2.91.

- ^ Proctor, M.F.; McLellan, B.N.; Strobeck, C (2002), "Population Fragmentation of Grizzly Bears in Southeastern British Columbia, Canda", Ursus, 13: 153–160.

- ^ Miller, S.D. 1990. Impact of increased bear hunting on survivorship of young bears. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 18: 462–467. Retrieved on October 27, 2009 from http://www.jstor.org/pss/3782749.

References

- "Ursus arctos horribilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- Banfield, A. W. F. (1987), The Mammals of Canada, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0802092298

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - CBC News article on possible "grolar bear" (Polar Bear/Grizzly Bear hybrid)

- Committee On The Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Assessment and Update Status Report on the Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos) in Canada, 2002 2.1 MB PDF file.

- Cronin, M. A. (1991), "Interspecific and specific mitochondrial DNA variation in North American bears (Ursus)", Canadian Journal of Zoology, 69: 2985–2992, doi:10.1139/z91-421.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Herrero, Stephen (1985), Bear Attacks, Piscataway, NJ: New Centuries Publishers, ISBN 0832903779

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Waits, L. P. (1998), "Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of the North American brown bear and implications for conservation", Conservation Biology, 12: 408–417, doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.96351.x.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Snyder, Susan (2003), The California Grizzly Bear in Mind, Berkeley: University of California Press

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Berger, J.; Stacey, Peter B; Bellis, Lori; Johnson, Matthew P (2001), "A Mammalian Predator-Prey Imbalance: Grizzly Bear and Wolf Extinction Affect Avian Neotropical Migrants", Ecological Applications, 11 (4): 947–960, doi:10.2307/3061004.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Mattson, J. (2001), "Extirpations of Grizzly Bears in the Contiguous United States, 1850–2000", Conservation Biology, 16 (4): 1123–1136, doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00414.x.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wielgus, R. B. (2002), "Minimum viable population and reserve sizes for naturally regulated grizzly bears in British Columbia", Biological Conservation, 106: 381–388, doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00265-8.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Tardiff, S. E. (1998), "Grizzly Bear Digging: Effects on Subalpine Meadow Plants in Relation to Mineral Nitrogen Availability", Ecology, 70 (7): 2219–2228, doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2219:GBDEOS]2.0.CO;2.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Groom, M. J. (2006), Principles of Conservation Biology (3rd ed.), Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Murie, Adolph (1985), The grizzlies of Mount McKinley, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 0295962046

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Knibb, David (2008), Grizzly Wars: The Public Fight Over the Great Bear, Eastern Washington University Press, ISBN 978-1-59766-037-2

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Peek, J., Beecham, J., Garshelis, D., Messier, F., Miller, S., & Dale, S. 2003. Management of Grizzly Bears in British Columbia: A Review by and Independent Scientific Panel. Retrieved on October 28, 2009 from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/gbear_finalspr.pdf.

- Michael, F.P., Bruce, N.M., & Curtis S. 2002. Population Fragmentation of Grizzly Bears in Southeastern British Columbia, Canada. Ursus, 8: 153–160. Retrieved on October 26, 2009 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3873196.

- McCory, W.P., Herrero, S.M., Jones, G.W., & Mallam, E.D. 1990. A Selection of Papers from the Eighth International Conference on Bear Research and Management, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Bears: Their Biology and Management, 8: 11–16.

- Krebs, C.J. 2009. Ecology: The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco.

- Miller, S.D. 1990. Impact of increased bear hunting on survivorship of young bears. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 18: 462–467. Retrieved on October 27, 2009 from http://www.jstor.org/pss/3782749.

- Proctor, M.F., McLellan, B.N., Strobeck, C., & Barclay, R.M.R. 2005. Genetic analysis reveals demographic fragmentation of grizzly bears yielding vulnerably small populations. Proc Biol Sci., 272: 2409–2416. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3246.

External links

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History species account-Grizzly Bear

- Are Grizzly Bears Dangerous?, grizzlybay.org

- Bear-ly with us: Is the fight to save Alberta's great Bear is a test case for protecting other endangered species in the province?

- Grizzly Bears in the Canadian Rockies

- The Yellowstone Grizzly