Fobos-Grunt: Difference between revisions

Unjustified removal of official reference. Deleted AGAIN unsuported info. |

Undid revision 485643650 by 119.40.118.34 (talk) |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

The spacecraft arrived at [[Baikonur cosmodrome|Baikonur]] on 17 October 2011 and was transported to Site 31 for pre-launch processing.<ref name=russianspaceweb_phobos_grunt_arrives_to_baikonur>[http://russianspaceweb.com/phobos_grunt_2011.html#baikonur Phobos-Grunt arrives to Baikonur]</ref> The Zenit-2SB41 rocket carrying Fobos-Grunt successfully lifted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome at 20:16 UTC on 8 November 2011.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://en.rian.ru/science/20111109/168527324.html|title=|author=|publisher=RIA Novosti|date=2011-11-09}}</ref> The Zenit booster inserted the spacecraft into an initial {{convert|207|x|347|km|abbr=on}} elliptical [[low Earth orbit]] with an inclination of 51.4 degrees.<ref name="psr_profile"/> |

The spacecraft arrived at [[Baikonur cosmodrome|Baikonur]] on 17 October 2011 and was transported to Site 31 for pre-launch processing.<ref name=russianspaceweb_phobos_grunt_arrives_to_baikonur>[http://russianspaceweb.com/phobos_grunt_2011.html#baikonur Phobos-Grunt arrives to Baikonur]</ref> The Zenit-2SB41 rocket carrying Fobos-Grunt successfully lifted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome at 20:16 UTC on 8 November 2011.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://en.rian.ru/science/20111109/168527324.html|title=|author=|publisher=RIA Novosti|date=2011-11-09}}</ref> The Zenit booster inserted the spacecraft into an initial {{convert|207|x|347|km|abbr=on}} elliptical [[low Earth orbit]] with an inclination of 51.4 degrees.<ref name="psr_profile"/> |

||

Two firings of the main propulsion unit in Earth orbit were required to send the spacecraft onto the interplanetary trajectory. Since both engine ignitions would have taken place outside the range of Russian ground stations, the project participants asked volunteers around the world to take optical observations of the burns, e.g. with telescopes, and report the results to enable more accurate prediction of the mission flight path upon entry into the range of Russian ground stations. |

Two firings of the main propulsion unit in Earth orbit were required to send the spacecraft onto the interplanetary trajectory. Since both engine ignitions would have taken place outside the range of Russian ground stations, the project participants asked volunteers around the world to take optical observations of the burns, e.g. with telescopes, and report the results to enable more accurate prediction of the mission flight path upon entry into the range of Russian ground stations. |

||

===Post-launch=== |

===Post-launch=== |

||

Revision as of 05:43, 6 April 2012

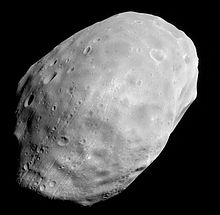

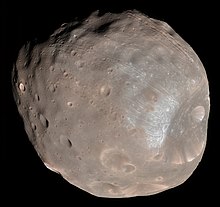

Fobos-Grunt or Phobos-Grunt (Russian: Фобос-Грунт, literally Phobos-Ground) was an attempted Russian sample return mission to Phobos, one of the moons of Mars. Fobos-Grunt also carried the Chinese Mars orbiter Yinghuo-1 and the tiny Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment funded by the Planetary Society.[1]

It was launched on 9 November 2011 at 02:16 local time (8 November 2011, 20:16 UTC) from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, but subsequent rocket burns intended to set the craft on a course for Mars failed, leaving it stranded in low Earth orbit.[2][3] Efforts to reactivate the craft were unsuccessful, and it fell back to Earth in an uncontrolled re-entry on January 15, 2012, reportedly over Pacific Ocean west of Chile.[4][5][6][7][8]

Funded by the Russian space agency Roscosmos and developed by NPO Lavochkin and the Russian Space Research Institute, Fobos-Grunt was the first Russian-led interplanetary mission since the failed Mars 96. The last successful Russian interplanetary missions were Vega 2 in 1985–1986, and the partially successful Fobos 2 in 1988–1989.[9] Fobos-Grunt was designed to become the first spacecraft to return a macroscopic sample from an extraterrestrial body since Luna 24 in 1976 (Hayabusa returned microscopic grains of asteroid material in 2010).[10] The return vehicle, carrying up to 200 g of soil from Phobos, was to have returned to Earth in August 2014.

Project history

Budget

The cost of the project was 1.5 billion rubles ($64.4 million USD).[11] Project funding for the timeframe 2009–2012, including post-launch operations, was about 2.4 billion rubles.[12] The total cost of the mission was to have been 5 billion rubles ($163 million).

According to lead scientist Alexander Zakharov, the entire spacecraft and most of the instruments were new, though the designs draw upon the nation's legacy of three successful Luna missions, which in the 1970s retrieved a few hundred grams of Moon rocks.[13] Zakharov had described the Phobos sample return project as "possibly the most difficult interplanetary one to date."[14]

Development

The Fobos-Grunt project began in 1999, when the Russian Space Research Institute and NPO Lavochkin, the main developer of Soviet and Russian interplanetary probes, initiated a 9 million rouble feasibility study into a Phobos sample-return mission. The initial spacecraft design was to be similar to the probes of the Fobos program launched in the late 1980s.[15] Development of the spacecraft started in 2001 and the preliminary design was completed in 2004.[11] For years, the project stalled as a result of low levels of financing of the Russian space program. This changed in the summer of 2005, when the new government plan for space activities in 2006–2015 was published. Fobos-Grunt was now made one of the program's flagship missions. With substantially improved funding, the launch date was set for October 2009. The 2004 design was revised a couple of times and international partners were invited to join the project.[15] In June 2006, NPO Lavochkin announced that it had begun manufacturing and testing the development version of the spacecraft's onboard equipment.[16]

On 26 March 2007, Russia and China signed a cooperative agreement on the joint exploration of Mars, which included sending China's first interplanetary probe, Yinghuo-1, to Mars together with the Fobos-Grunt spacecraft.[17] Yinghuo-1 weighed 115 kg (250 pounds) and would have been released by the main spacecraft into a Mars orbit.[18]

Partners

The main project contractor was NPO Lavochkin, which was responsible for components' development. The Chief Designer of Fobos-Grunt was Maksim Martynov.[19] Phobos soil sampling and downloading were developed by the GEOHI RAN Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Vernadski Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical chemistry) and the integrated scientific studies of Phobos and Mars by remote and contact methods were the responsibility of the Russian Space Research Institute,[20] where the lead scientist of the mission was Alexander Zakharov.[14]

The Chinese Yinghuo-1 orbiter was launched together with Fobos-Grunt.[21] In late 2012, after a 10-11.5 month cruise, Yinghuo-1 would have separated and entered a 800×80,000 km equatorial orbit (5° inclination) with a period of three days. The spacecraft was expected to remain on Martian orbit for one year. Yinghuo-1 would have focused mainly on the study of the external environment of Mars. Space center researchers expected to use photographs and data to study the magnetic field of Mars and the interaction between ionospheres, escape particles and solar wind.[22]

A second Chinese payload, the Soil Offloading and Preparation System (SOPSYS), was integrated in the lander. SOPSYS was a microgravity grinding tool developed by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.[23][24]

Another payload on Fobos-Grunt was an experiment from the Planetary Society called Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment; its goal was to test whether selected organisms can survive a few years in deep space by flying them through interplanetary space. The experiment would have tested one aspect of transpermia, the hypothesis that life could survive space travel, if protected inside rocks blasted by impact off one planet to land on another.[25][26][27][28][29]

The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences contributed with a radiation measurement experiment on Fobos-Grunt.[30] Two MetNet Mars landers developed by the Finnish Meteorological Institute, were planned to be included as payload of the Fobos-Grunt mission,[31][32] but weight constraints on the spacecraft required dropping the MetNet landers from the mission.[12]

Skipped 2009 launch

The October 2009 launch date could not be achieved due to delays in the spacecraft development. During 2009, officials admitted that the schedule was very tight, but still hoped until the last moment that a launch could be made.[28] On 21 September 2009 the mission was officially announced to be delayed until the next launch window in 2011.[33][34][12][35] A main reason for the delay was difficulties encountered during development of the spacecraft's onboard computers. While the Moscow-based company Tehkhom provided the computer hardware on time, the internal NPO Lavochkin team responsible for integration and software development fell behind schedule.[36] The retirement of NPO Lavochkin's head Valeriy N. Poletskiy in January 2010 was widely seen as linked to the delay of Fobos-Grunt. Viktor Khartov was appointed the new head of the company. During the extra development time resulting from the delay, a Polish-built drill was added to the Phobos lander as a back-up soil extraction device.[37]

2011 launch

The spacecraft arrived at Baikonur on 17 October 2011 and was transported to Site 31 for pre-launch processing.[38] The Zenit-2SB41 rocket carrying Fobos-Grunt successfully lifted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome at 20:16 UTC on 8 November 2011.[39] The Zenit booster inserted the spacecraft into an initial 207 km × 347 km (129 mi × 216 mi) elliptical low Earth orbit with an inclination of 51.4 degrees.[40]

Two firings of the main propulsion unit in Earth orbit were required to send the spacecraft onto the interplanetary trajectory. Since both engine ignitions would have taken place outside the range of Russian ground stations, the project participants asked volunteers around the world to take optical observations of the burns, e.g. with telescopes, and report the results to enable more accurate prediction of the mission flight path upon entry into the range of Russian ground stations.

Post-launch

- Baikonour launch

- First Burn

- Spent fuel tank ejected

- Second Burn (Departure to Martian system)

It was expected that after 2.5 hours and 1.7 revolutions in the initial orbit, the autonomous main propulsion unit (MDU), derived from the Fregat upper stage, would conduct its firing to insert the spacecraft into the elliptical orbit (250 km x 4,150-4,170 km) with a period of about 2.2 hours. After the completion of the first burn, the external fuel tank of the propulsion unit was expected to be jettisoned, with ignition for a second burn to depart Earth orbit scheduled for one orbit, or 2.1 hours, after the end of the first burn.[40][41][42] The propulsion module constitutes the cruise-stage bus of Fobos-Grunt. According to original plans, Mars orbit arrival had been expected during September 2012 and the return vehicle was scheduled to reach Earth in August 2014.[20][43]

However, following what would have been the planned end of the first burn the spacecraft could not be located in the target orbit. The spacecraft was subsequently discovered to still be in its initial parking orbit,[2] and it was determined that the burn had not taken place.[44] Initially, engineers had about three days from launch to rescue the spacecraft before its batteries ran out.[18] It was then established that the craft's solar panels had deployed, giving engineers more time to restore control. It was soon discovered the spacecraft was adjusting its orbit, changing its expected re-entry from late November or December to as late as early 2012.[45] Even though it had not been contacted, the spacecraft seemed to be actively adjusting its perigee (the point it is closest to Earth in its orbit).[45][46][47]

By 22 November 2011, attempts to establish connection with the probe were unsuccessful.[48]

Contact

On 22 November 2011, a signal from the probe was picked up by the European Space Agency's tracking station in Perth, Australia, after it had sent the probe the command to turn on one of its transmitters. The European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt reported that the contact was made at 20:25 UTC on 22 November 2011 after some modifications had been made to the 15 m dish facility in Perth to improve its chances of getting a signal.[49] No telemetry was received in this communication.[50] It remained unclear whether the communications link would have been sufficient to command the spacecraft to switch on its engines to take it on its intended trajectory toward Mars.[51] Roscosmos officials said that the window of opportunity to salvage Fobos-Grunt would close in early December.[51]

The next day, on 23 November, the Perth station again made contact with the spacecraft and during this contact about 400 telemetry "frames" and Doppler information were received.[52] This contact lasted six minutes.[53][54] The amount of information received during this communication was not sufficient, and therefore it was not possible to identify the problem with the probe.[54][55] Further communication attempts made by ESA were unsuccessful and contact was not reestablished.[56] The space vehicle did not respond to the commands sent by the European Space Agency to raise its orbit.[56] Roscosmos provided these commands to ESA.[52]

From Baikonour, Kazakhstan, Roscosmos was able to receive telemetry from Fobos-Grunt on 24 November[57] but attempts to contact it failed.[56] This telemetry demonstrated that the probe's radio equipment was working and that it was communicating with the spacecraft's flight control systems.[57] Moreover, Roscosmos's top officials believed Fobos-Grunt to be functional, stably oriented and charging batteries through its solar panels.[50]

In a late November 2011 interview, the service manager of the European Space Agency for Fobos-Grunt, Wolfgang Hell, stated that Roscosmos had a better understanding of the problem with the spacecraft, saying they reached the conclusion that they have some kind of power problem onboard.[58]

ESA failed to communicate with the space probe in all of the five opportunities the agency had between 28 November and 29 November. During those occasions the spacecraft did not comply with orders to fire the engines and raise its orbit. The Russian space agency then requested that ESA repeat the orders.[59] The European Space Agency decided to end the efforts to contact the probe on 2 December 2011. However, ESA made teams available to assist the Fobos-Grunt mission if indicated by any change in situation.[60] In spite of that Roscosmos stated their intention to continue to try to contact the space vehicle until it entered "the thicker layers of the atmosphere."[61]

The US Strategic Command’s Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) tracked the probe[62] and identified at the start of December that Fobos-Grunt had an elliptical orbit at an altitude of between 130 miles (209 km) and 190 miles (305 km), but falling a few miles each day.[63]

Re-entry

Before reentry, the spacecraft still carried about 7.51 metric tonnes of highly toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide on board.[3][18] This was mostly fuel for the spacecraft's upper stage. These compounds, with melting points of 2°C and -11.2°C, are normally kept in liquid form and were expected to burn out during re-entry.[18] NASA veteran James Oberg said the hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide "could freeze before ultimately entering", thus contaminating the impact area.[3] He also stated that if Fobos-Grunt is not salvaged, it may be the most dangerous object to fall from orbit.[3] Meanwhile, the head of Roscomos said the probability of parts reaching the Earth surface was "highly unlikely", and that the spacecraft, including the LIFE module and the Yinghuo-1 orbiter, would be destroyed during re-entry.[18]

Russian military sources claimed that Fobos-Grunt was somewhere over the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and South America when it re-entered the atmosphere at about 17:45 UTC.[64] Although it was initially feared its remains would reach land as close as 145 km west of Santa Fe, Argentina, the Russian military Air and Space Defense Forces reported that it ultimately fell into the Pacific Ocean, 775 miles (1,247 km) west of Wellington Island, Chile.[5] The Defence Ministry spokesman subsequently revealed that such estimate was based on calculations, without witness reports. In contrast, Russian civilian ballistic experts said that the fragments had fallen over a broader patch of Earth's surface, and that the midpoint of the crash zone was located in the Goiás state of Brazil.[65][66][67]

It was hoped that the re-entry capsule might be recovered, giving at least some scientific information in the form of engineering assessment of the capsule design, and life sciences data with the LIFE module.[68][69]

Aftermath

Initially, the head of Roscosmos Vladimir Popovkin, suggested that the Fobos-Grunt failure of might have been the result of sabotage by a foreign nation.[70][71] He also stated that risky technical decisions had been made because of limited funding. On 17 January 2012, an unidentified Russian official speculated that a U.S. radar stationed on the Marshall Islands may have inadvertently disabled the probe, but cited no evidence.[72] Popovkin suggested the microchips may have been counterfeit,[73][74] then he announced on February 1 that a burst of cosmic radiation may have caused computers to reboot and go into a standby mode. Industry experts cast doubt on the claim citing the how unlikely effects of such a burst are in low earth orbit, inside the protective Earth's magnetic field.[75]

On February 6, 2012, the commission investigating the mishap concluded that Fobos-Grunt mission failed because "a programming error which led to a simultaneous reboot of two working channels of an onboard computer." The craft's rocket pack never fired because of the computer reboot, leaving the craft stranded in Earth orbit.[76][77] Russian president Dmitry Medvedev suggested that those responsible should be punished and perhaps criminally prosecuted.[78][79]

On January 2012, Vladimir Popovkin called for a repeat sample return mission called Fobos-Grunt-2, for launch in 2018 as an improved and simplified version, expecting to be costing less than its predecessor. It would utilize the Soyuz-Fregat launch vehicle rather than a Zenit rocket. He also stated that if Russia was not included in the European Space Agency's ExoMars program, it would attempt to repeat the Fobos-Grunt mission.[80][81][82][83] On March 15 2012, ESA announced an agreement had been reached for the inclusion of Russia as a full project partner.[84][85][86] This meant that the mision will not be repeated, and the insurance money from Fobos-Grunt would go to ExoMars instead.[87]

Objectives

Fobos-Grunt was an intended interplanetary probe that included a lander to study Phobos and a sample return vehicle to return a sample of about 200 g (7.1 oz) of soil to Earth.[88] It was also to study Mars from orbit, including its atmosphere and dust storms, plasma and radiation.

- Science goals

- Delivery of samples of Phobos soil to Earth for scientific research of Phobos, Mars and Martian vicinity;

- In situ and remote studies of Phobos (to include analysis of soil samples);

- Monitoring the atmospheric behavior of Mars, including the dynamics of dust storms;

- Studies of the vicinity of Mars, including its radiation environment, plasma and dust;[20]

- Study of the origin of the Martian moons and their relation to Mars;

- Study of the role played by asteroid impacts in the formation of terrestrial planets;

- Search for possible past or present life (biosignatures);[89]

- Study of the impact of a three year interplanetary round-trip journey to extremophile microorganisms in a small sealed capsule (LIFE experiment).[90]

Payload

- TV system for navigation and guidance[91]

- Gas-Chromatograph package:[92]

- Thermal Differential Analyzer

- Gas-Chromatograph

- Mass-Spectrometer

- Gamma ray spectrometer[93]

- Neutron spectrometer[93]

- Alpha X spectrometer[93]

- Seismometer[93]

- Long-wave radar[93]

- Visual and near-infrared spectrometer[93]

- Dust counter[93]

- Ion spectrometer[93]

- Optical solar sensor[94]

Mission plan

Journey

The spacecraft's journey to Mars would take about ten months. After arriving in Mars orbit, the main propulsion unit and the transfer truss would separate and the Chinese Mars orbiter would be released. Fobos-Grunt would then spend several months studying the planet and its moons from orbit, before landing on Phobos.

On Phobos

The planned landing site at Phobos was a region from 5°S to 5°N, 230° to 235°E.[95] Soil sample collection would begin immediately after the lander touched down on Phobos, with collection lasting 2–7 days. An emergency mode existed for the case of communications breakdown, which enabled the lander to automatically launch the return rocket to deliver the samples to Earth.[96]

A robotic arm would have collected samples up to 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) in diameter. At the end of the arm was a pipe-shaped tool which split to form a claw. The tool contained a piston which would have pushed the sample into a cylindrical container. A light-sensitive photo-diode would have confirmed whether material collection was successful and also allowed visual inspection of the digging area. The sample extraction device would have performed 15 to 20 scoops yielding a total of 3 to 5.5 ounces (85 to 156 g) of soil.[96] The samples would be loaded into a capsule which would then be moved inside a special pipeline into the descent module by inflating an elastic bag within the pipe with gas.[11][97] Because the characteristics of Phobos soil are uncertain, the lander included another soil-extraction device, a Polish-built drill, which would have been used in case the soil turned out to be too rocky for the main scooping device.[10][37]

After the departure of the return stage, the lander's experiments would have continued in situ on Phobos' surface for a year. To conserve power, mission control would have turned these on and off in a precise sequence. The robotic arm would have placed more samples in a chamber that would heat it and analyze its Emission spectra. This analysis might have been able to determine the presence of volatile compounds, such as water.[96]

Sample return to Earth

The return stage was mounted on top of the lander. It would have needed to accelerate to 35 km/h (22 mph) to escape Phobos' gravity. In order to avoid harming the experiments remaining at the lander, the return stage would have ignited its engine once the vehicle had been vaulted to a safe height by springs. It would then have begun maneuvers for the eventual trip to Earth, where it would have arrived in August 2014.[96] An 11-kg descent vehicle containing the capsule with soil samples (up to 0.2 kg (0.44 lb)) would have been released on direct approach to Earth at 12 km/s (7.5 mi/s).[92] Following the aerodynamic braking to 30 m/s (98 ft/s) the conical-shaped descent vehicle would perform a hard landing without a parachute within the Sary Shagan test range in Kazakhstan.[97] The vehicle did not have any radio equipment.[10] Ground-based radar and optical observations would have been used to track the vehicle's return.[98]

Ground control

The mission control center was located at the Center for Deep Space Communications (Национальный центр управления и испытаний космических средств Template:Ref-ru, Євпаторійський центр дальнього космічного зв'язку Template:Ref-uk) equipped with RT-70 radio telescope near Yevpatoria in the Crimea, Ukraine.[99] Russia and Ukraine agreed in late October 2010 that the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, would have controlled the probe.[100]

Communications with the spacecraft on the initial parking orbit are described in a two-volume publication.[101]

Critiques

Barry E. DiGregorio, Director of the International Committee Against Mars Sample Return, criticised the LIFE experiment carried by Fobos-Grunt as a violation of the Outer Space Treaty due to the possibility of contamination of Phobos or Mars with the microbial spores and live bacteria it contains should it have lost control and crash-landed on either body.[102] It is speculated that the heat-resistant extremophile bacteria could survive such a crash, on the basis that Microbispora bacteria survived the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.[103]

According to Fobos-Grunt Chief Designer Maksim Martynov, the probability of the probe accidentally reaching the surface of Mars was much lower than the maximum specified for Category III missions, the type assigned to Fobos-Grunt and defined in COSPAR's planetary protection policy (in accordance with Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty).[97][104]

References

- ^ Jonathan Amos (9 November 2011). "Phobos-Grunt Mars probe loses its way just after launch". BBC.

- ^ a b Molczan, Ted (9 November 2011). "Phobos-Grunt - serious problem reported". SeeSat-L. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Vladimir Ischenkov - Russian scientists struggle to save Mars moon probe (9 November 2011) - Associated Press

- ^ "Russia's failed Phobos-Grunt space probe heads to Earth", BBC News, 14 January 2012

- ^ a b "Russian space probe crashes into Pacific Ocean". Fox News. 15 January 2012.

- ^ "Did a U.S. radar mistakenly send Russia's $170m Mars probe into the Pacific?", Daily Mail, 18th January 2012

- ^ "Russia asks if US radar ruined Phobos-Grunt space probe", msnbc.com, 17 January 2012

- ^ "Maybe Brazil... or possibly off the coast of Chile?", Daily Mail, 16th January 2012

- ^ "Jonathan's Space Report No. 650 2011 Nov 16".

- ^ a b c "Daring Russian Sample Return mission to Martian Moon Phobos aims for November Liftoff". Universe Today. 2011-10-13.

- ^ a b c Zaitsev, Yury (14 July 2008). "Russia to study Martian moons once again". RIA Novosti.

- ^ a b c Zak, Anatoly. "Preparing for flight". Russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ "Russia takes aim at Phobos". Nature. 2011-11-04.

- ^ a b "Mars Moon Lander to Return Russia to Deep Space". The Moscow Times. 08 Nov 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. pp. 326–330. ISBN 978-0-387-71354-0.

- ^ "Russia to test unmanned lander for Mars moon mission". RIA Novosti. 2010-09-09.

- ^ "China to launch probe to Mars with Russian help in 2009". RIA Novosti. 2008-12-05.

- ^ a b c d e http://www.space.com/13618-russia-phobos-grunt-mars-spacecraft-silent.html

- ^ Biography of Maksim MartynovTemplate:Ref-ru

- ^ a b c "Phobos-Grunt". European Space Agency. October 25, 2004. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (May 21, 2007). "With a Russian hitch-hike, China heading to Mars". NASAspaceflight.

- ^ "China and Russia join hands to explore Mars". People's Daily Online. May 30, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- ^ Zhao, Huanxin (27 March 2007). "Chinese satellite to orbit Mars in 2009". China Daily.

- ^ "HK triumphs with out of this world invention". HK Trader. 1 May 2007.

- ^ "Projects: LIFE Experiment: Phobos". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Living interplanetary flight experiment (LIFE): An experiment on the survivalability of microorganisms during interplanetary travel

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (1 September 2008). "Mission Possible". Air & Space Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ a b Zak, Anatoly (2008-09-01). "Mission Possible - A new probe to a Martian moon may win back respect for Russia's unmanned space program". AirSpaceMag.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ "LIFE Experiment: Phobos". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "Проект "Люлин-Фобос" - "Радиационно сондиране по трасето Земя-Марс в рамките на проекта "Фобос-грунт"". Международен проект по програмата за академичен обмен между ИКСИ-БАН и ИМПБ при АН на Русия - (2011-2015)". Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ "MetNet Mars Precursor Mission". Finnish Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Space technology – a forerunner in Finnish-Russian high-tech cooperation". Energy & Enviro Finland. 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt probe launch is postponed to 2011" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 2009-09-21. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "Russia delays Mars probe launch until 2011: report". Space Daily. 16 September 2009.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (2009-04). "Russia to Delay Martian Moon Mission". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Industry Insiders Foresaw Delay of Russia's Phobos-Grunt". Space News. 2009-10-05.

- ^ a b "Difficult rebirth for Russian space science". BBC News. 2010-06-29.

- ^ Phobos-Grunt arrives to Baikonur

- ^ . RIA Novosti. 2011-11-09 http://en.rian.ru/science/20111109/168527324.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Mission profile Phobos-Soil project

- ^ "Phobos-Grunt to be launched to Mars on Nov 8". Interfax News. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt space probe is moved to a refueling station". Roscosmos. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-21.Template:Ref-ru

- ^ "Timeline for the Phobos Sample Return Mission (Phobos Grunt)". Planetary Society. October 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ "Маршевая двигательная установка станции "Фобос-Грунт" не сработала" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b David Warmflash, M.D. - Phobos-Grunt's Mysterious Thruster Activation: A Function of Safe Mode or Just Good Luck? (16 November 2011) - Universe Today

- ^ http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/11/15/60435756.html

- ^ http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/11/14/60345638.html

- ^ "Роскосмос признал, что шансов реализовать миссию "Фобос-Грунт" практически не осталось" (in Russian).

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (23 November 2011). "Signal picked from Russia's stranded Mars probe". BBC News.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (23 November 2011). "It's alive! Russia's Phobos-Grunt probe phones home". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ a b http://www.spacenews.com/civil/111123-esa-establishes-contact-with-phobos-grunt-spacecraft.html ESA Makes Contact with Russia’s Stranded Phobos-Grunt Spacecraft

- ^ a b http://www.spaceflightnow.com/news/n1111/25phobosgrunt/

- ^ "ESA receives telemetry from Russian Mars probe". Ria Novosti. 24 November 2011.

- ^ a b http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/45413483/

- ^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/45529538/ns/technology_and_science-space/t/phobos-grunt-dead-esa-stop-trying-contact-probe/

- ^ a b c http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/45529424

- ^ a b http://en.rian.ru/science/20111125/169033219.html

- ^ http://www.space.com/13710-phobos-grunt-rescue-time-running.html

- ^ http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/258297/20111130/phobos-grunt-esa-slatest-orbit-raising-maneuvers.htm

- ^ Chow, Denise (2 December 2011). "Is Phobos-Grunt dead? Europeans end rescue effort". msnbc.com. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ http://en.rian.ru/science/20111124/169008082.html

- ^ http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1968/1.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Most Popular E-mail Newsletter". USA Today. 1 December 2011.

- ^ Zolotukhin, Alexei (January 15, 2012). "Russian Phobos-Grunt Mars probe falls in Pacific Ocean". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

Phobos-Grunt fragments have crashed down in the Pacific Ocean

- ^ Enoch, Nick (January 16, 2012). "Maybe Brazil... or possibly off the coast of Chile? Russian officials admit having no idea where failed Mars probe has crashed". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Ballistics confirmed the coordinates of the fall of the "Phobos-Grunt" (Google Translate from Russian: Баллистики подтвердили координаты точки падения "Фобос-Грунта")". RIA Novosti. January 16, 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Sanderson, Katharine (January 18, 2012). "Phobos-Grunt Crashes Into the Pacific". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Universe Today, "Russian Space Program Prepares for Phobos-Grunt Re-Entry", David Warmflash, 13 December 2011

- ^ Emily Lakdawalla (January 13, 2012). "Bruce Betts: Reflections on Phobos LIFE". The Planetary Society Blog. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ^ "Foreign sabotage suspected in Phobos-Grunt meltdown", theregister.co.uk, 10th January 2012

- ^ "Russian space chief claims space failures may be sabotage", msnbc.com, 10 January 2012

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 January 2012 http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/oops-radar-may-have-caused-space-crash-20120117-1q4ea.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Phobos-Grunt chips supposedly were counterfeit". ITAR-TASS News Agency. January 31, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

heavy charged particles of space, which caused malfunction of the memory system during the second circuit in the orbit ... may have been counterfeit

- ^ Oberg, James (16 February 2012). "Did Bad Memory Chips Down Russia's Mars Probe?". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Russia Places Phobos-Grunt Failure Blame

- ^ Clark, Stephen (6 February 2012). "Russia: Computer crash doomed Phobos-Grunt". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Programmers are to be blamed for the failure of Phobos mission". ITAR-TASS News Agency. January 31, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ http://blogs.nature.com/news/2011/11/medvedev_punishment_awaits_tho_1.html

- ^ "Medvedev suggests prosecution for Russia space failure". Reuters. 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Russian Lavochkin Center chief calls for new Phobos missions". kyivpost. 2012-01-24. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Warmflash, David (2011-12-08). "Scientist: Russia's Failed Mars' Moon Probe Worth a Second Try". Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Olga, Zakutnyaya (February 2, 2012). Russian and India Report [Russia's ambitious space projects: Phobos-Grunt-2? Russia's ambitious space projects: Phobos-Grunt-2?]. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Russia May Run Repeat Mission to Phobos". RIA Novosti. 2012-01-31. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Europe still keen on Mars missions". BBC News. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Europe Joins Russia on Robotic ExoMars". Aviation Week. Mar 16, 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "ESA Ruling Council OKs ExoMars Funding". Space News. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Insurance from "Phobos-Grunt" to fly to Mars". Gazeta (in Russian). 30 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Fobos-Grunt sent to Baikonur Template:Ref-ru

- ^ Korablev, O. "Russian programme for deep space exploration" (PDF). Space Research Institute (IKI). p. 14.

- ^ "Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment (LIFE)". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "Optico-electronic Instruments for the Phobos-Grunt Mission". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ a b Phobos Soil - Spacecraft European Space Agency

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-71354-0.

- ^ "Optical Solar Sensor". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ "Phobos Flyby Images: Proposed Landing Sites for the Forthcoming Phobos-Grunt Mission". Science Daily. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zak. "Mission Possible".

- ^ a b c "Russia resumes missions to outer space: what is after Phobos?".Template:Ref-ru

- ^ The mission scenario of the Phobos-Grunt project Anatoly Zak

- ^ Russian spacecraft for Fobos-Grunt program to be controlled from Yevpatoria, Kyiv Post (June 25, 2010)

- ^ "Russia's Phobos Grunt to head for Mars on November 9". Itar Tass. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Fobos-Grunt sample return mission.Template:Ref-ru

- ^ DiGregorio, Barry E. (2010-12-28). "Don't send bugs to Mars". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ McLean, R; Welsh, A; Casasanto, V (2006). "Microbial survival in space shuttle crash". Icarus. 181 (1): 323–325. Bibcode:2006Icar..181..323M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.002. PMC 3144675. PMID 21804644.

- ^ "COSPAR Planetary Protection Policy".

Further reading

- M. Ya. Marov, V. S. Avduevsky, E. L. Akim, T. M. Eneev, R. S. Kremnevich, S. D. Kulikovich, K. M. Pichkhadzec, G. A. Popov, G. N. Rogovshyc (2004). "Phobos-Grunt: Russian sample return mission". Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2276–2280. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.2276M. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00515-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Galimov, E. M. (2010). "Phobos sample return mission: Scientific substantiation". Solar System Research. 44: 5. Bibcode:2010SoSyR..44....5G. doi:10.1134/S0038094610010028.

- Zelenyi, L. M.; Zakharov, A. V. (2010). "Phobos-Grunt project: Devices for scientific studies". Solar System Research. 44 (5): 359. Bibcode:2010SoSyR..44..359Z. doi:10.1134/S0038094610050011.

- Rodionov, D. S.; Klingelhoefer, G.; Evlanov, E. N.; Blumers, M.; Bernhardt, B.; Gironés, J.; Maul, J.; Fleischer, I.; Prilutskii, O. F. (2010). "The miniaturized Möessbauer spectrometer MIMOS II for the Phobos-Grunt mission". Solar System Research. 44 (5): 362. Bibcode:2010SoSyR..44..362R. doi:10.1134/S0038094610050023.