Sucralose: Difference between revisions

Only stability is compared in the citation |

→History: citation doesn't say 'nontraditional' or 'chemical intermediaries' Rather it says 'searching for possible synthetic industrial applications of sucrose' |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Sucralose was discovered in 1976 by scientists from [[Tate & Lyle]], working with researchers Leslie Hough and Shashikant Phadnis at [[Queen Elizabeth College]] (now part of [[King's College London]]).<ref name="sucralose.org"/> While researching ways to use sucrose |

Sucralose was discovered in 1976 by scientists from [[Tate & Lyle]], working with researchers Leslie Hough and Shashikant Phadnis at [[Queen Elizabeth College]] (now part of [[King's College London]]).<ref name="sucralose.org"/> While researching ways to use sucrose and its synthetic derivatives for industrial applications, Phadnis was told to test a chlorinated sugar compound. Phadnis thought Hough asked him to 'taste' it, so he did.<ref name="Gratzer2002">{{cite book|last=Gratzer|first=Walter |title=Eurekas and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=4eTIxt6sN2oC&pg=PT32|accessdate=1 August 2012|date=28 November 2002|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-280403-7|pages=32–|chapter=5. Light on sweetness: the discovery of aspartame}}</ref> He found the compound to be exceptionally sweet. |

||

Tate & Lyle patented the substance in 1976; as of 2008, the only remaining patents concern specific manufacturing processes.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.ap-foodtechnology.com/Processing/Tate-Lyle-loses-sucralose-patent-case | title = Tate & Lyle loses sucralose patent case | publisher = ap-foodtechnology.com}}</ref> |

Tate & Lyle patented the substance in 1976; as of 2008, the only remaining patents concern specific manufacturing processes.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.ap-foodtechnology.com/Processing/Tate-Lyle-loses-sucralose-patent-case | title = Tate & Lyle loses sucralose patent case | publisher = ap-foodtechnology.com}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:50, 3 November 2012

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

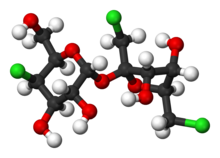

1,6-Dichloro-1,6-dideoxy-β-D-fructofuranosyl-4-chloro-4-deoxy-α-D-galactopyranoside

| |

| Other names

1',4,6'-Trichlorogalactosucrose

Trichlorosucrose E955, 4,1',6'-Trichloro-4,1',6'-trideoxygalactosucrose, TGS, Splenda [2] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.054.484 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E955 (glazing agents, ...) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H19Cl3O8 | |

| Molar mass | 397.64 g/mol |

| Melting point | 125 °C (257 °F; 398 K) |

| 283 g/L (20°C) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Sucralose is an artificial sweetener. The majority of ingested sucralose is not broken down by the body, so is noncaloric.[3] In the European Union, it is also known under the E number (additive code) E955. Sucralose is approximately 600 times as sweet as sucrose (table sugar),[4] twice as sweet as saccharin, and three times as sweet as aspartame. It is stable under heat and over a broad range of pH conditions. Therefore, it can be used in baking or in products that require a longer shelf life. The commercial success of sucralose-based products stems from its favorable comparison to other low-calorie sweeteners in terms of taste, stability, and safety.[5][failed verification] Common brand names of sucralose-based sweeteners are Splenda, Sukrana, SucraPlus, Candys, Cukren and Nevella.

History

Sucralose was discovered in 1976 by scientists from Tate & Lyle, working with researchers Leslie Hough and Shashikant Phadnis at Queen Elizabeth College (now part of King's College London).[3] While researching ways to use sucrose and its synthetic derivatives for industrial applications, Phadnis was told to test a chlorinated sugar compound. Phadnis thought Hough asked him to 'taste' it, so he did.[6] He found the compound to be exceptionally sweet.

Tate & Lyle patented the substance in 1976; as of 2008, the only remaining patents concern specific manufacturing processes.[7]

Sucralose was first approved for use in Canada in 1991. Subsequent approvals came in Australia in 1993, in New Zealand in 1996, in the United States in 1998, and in the European Union in 2004. By 2008, it had been approved in over 80 countries, including Mexico, Brazil, China, India and Japan.[8] In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration amended the regulations for foods to include sucralose as a non-nutritive sweetener in food.[9] In May 2008, Fusion Nutraceuticals launched a generic product to the market, using Tate & Lyle patents.

Production

Tate & Lyle manufactures sucralose at a plant in Jurong, Singapore.[10] Formerly, it was produced at a plant in McIntosh, Alabama. It is manufactured by the selective chlorination of sucrose (table sugar), which substitutes three of the hydroxyl groups with chlorine. This chlorination is achieved by selective protection of the primary alcohol groups followed by acetylation and then deprotection of the primary alcohol groups. Following an induced acetyl migration on one of the hydroxyl groups, the partially acetylated sugar is then chlorinated with a chlorinating agent such as phosphorus oxychloride, followed by removal of the acetyl groups to give sucralose.[11]

Product uses

Sucralose can be found in more than 4,500 food and beverage products. It is used because it is a no-calorie sweetener, and does not promote dental cavities,[12] is safe for consumption by diabetics,[13][14][15] and does not affect insulin levels.[16] Sucralose is used as a replacement for, or in combination with, other artificial or natural sweeteners, such as aspartame, acesulfame potassium or high-fructose corn syrup. Sucralose is used in products such as candy, breakfast bars and soft drinks. It is also used in canned fruits wherein water and sucralose take the place of much higher calorie corn syrup-based additives. Sucralose mixed with maltodextrin or dextrose (both made from corn) as bulking agents is sold internationally by McNeil Nutritionals under the Splenda brand name. In the United States and Canada, this blend is increasingly found in restaurants, including McDonald's, Tim Hortons and Starbucks, in yellow packets, in contrast to the blue packets commonly used by aspartame and the pink packets used by those containing saccharin sweeteners; in Canada, though, yellow packets are also associated with the SugarTwin brand of cyclamate sweetener.

Cooking

Sucralose is a highly heat-stable artificial sweetener, allowing it to be used in many recipes with little or no sugar. It is available in a granulated form that allows for same-volume substitution with sugar. This mix of granulated sucralose includes fillers, all of which rapidly dissolve in liquids. While the granulated sucralose provides apparent volume-for-volume sweetness, the texture in baked products may be noticeably different. Sucralose is not hygroscopic, meaning it does not attract moisture, which can lead to baked goods that are noticeably drier and manifesting a less dense texture than those made with sucrose. Unlike sucrose, which melts when baked at high temperatures, sucralose maintains its granular structure when subjected to dry, high heat (e.g., in a 350 °F or 180 °C oven). Furthermore, in its pure state, sucralose begins to decompose into other substances at temperatures above 119 °C or 246 °F.[17] Thus, in some baking recipes, such as crème brûlée, which require sugar sprinkled on top to partially or fully melt and crystallize, substituting sucralose will not result in the same surface texture, crispness, or crystalline structure.

Packaging and storage

Pure sucralose is sold in bulk, but not in quantities suitable for individual use, although some highly concentrated sucralose-water blends are available online, using 1/4 teaspoon per one cup of sweetness or roughly one part sucralose to two parts water.[18] Pure, dry sucralose undergoes some decomposition at elevated temperatures. In solution or blended with maltodextrin, it is slightly more stable. Most products containing sucralose add fillers and additional sweetener to bring the product to the approximate volume and texture of an equivalent amount of sugar.

Effect on caloric content

Though sucralose itself contains no calories, products that contain fillers, such as maltodextrin and/or dextrose, add about 2-4 calories per teaspoon or individual packet, depending on the product, the fillers used, brand, and the intended use of the product.[19] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allows for any product containing less than five calories per serving to be labeled as "zero calories".[20]

Health, safety, and regulation

Sucralose has been accepted by several national and international food safety regulatory bodies, including the FDA, Joint Food and Agriculture Organization / World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives, the European Union's Scientific Committee on Food, Health Protection Branch of Health and Welfare Canada, and Food Standards Australia-New Zealand (FSANZ). Sucralose is one of two artificial sweeteners ranked as "safe" by the consumer advocacy group Center for Science in the Public Interest. The other is neotame.[21][22][23] According to the Canadian Diabetes Association, the amount of sucralose that can be consumed on a daily basis over a person’s lifetime without any adverse effects is 9 milligrams per kilogram of body weight.[24][25]

"In determining the safety of sucralose, the FDA reviewed data from more than 110 studies in humans and animals. Many of the studies were designed to identify possible toxic effects, including carcinogenic, reproductive, and neurological effects. No such effects were found, and FDA's approval is based on the finding that sucralose is safe for human consumption." For example, McNeil Nutritional LLC studies submitted as part of its U.S. FDA Food Additive Petition 7A3987 indicated that "in the 2-year rodent bioassays...there was no evidence of carcinogenic activity for either sucralose or its hydrolysis products..."[26]

Safety studies

Results from over 100 animal and clinical studies in the FDA approval process unanimously indicated a lack of risk associated with sucralose intake.[27][28][29][30] However, some adverse effects were seen at doses that significantly exceeded the estimated daily intake (EDI), which is 1.1 mg/kg/day.[31] When the EDI is compared to the intake at which adverse effects are seen, known as the highest no adverse effects limit (HNEL), at 1500 mg/kg/day,[31] there is a large margin of safety. The bulk of sucralose ingested is not absorbed by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and is directly excreted in the feces, while 11-27% of it is absorbed.[4] The amount absorbed from the GI tract is largely removed from the blood stream by the kidneys and eliminated in the urine, with 20-30% of the absorbed sucralose being metabolized.[4]

Environmental effects

According to one study, sucralose is digestible by a number of microorganisms and is broken down once released into the environment.[32] However, measurements by the Swedish Environmental Research Institute have shown wastewater treatment has little effect on sucralose, which is present in wastewater effluents at levels of several μg/l (ppb).[33] There are no known ecotoxicological effects at such levels, but the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency warns there may be a continuous increase in levels if the compound is only slowly degraded in nature.[34]

Other potential effects

A Duke University study[35] found evidence that doses of Splenda of between 100 and 1000 mg/kg, containing sucralose at 1.1 to 11 mg/kg (compare to the FDA Acceptable Daily Intake of 5 mg/kg), reduced the amount of fecal microflora in rats by up to 50%, increased the pH level in the intestines, contributed to increases in body weight, and increased levels of P-glycoprotein (P-gp).[36] These effects have not been reported in humans.[4] An expert panel, including scientists from Rutgers University, New York Medical College, Harvard School of Public Health, Columbia University, and Duke University reported in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology that the Duke study was "not scientifically rigorous and is deficient in several critical areas that preclude reliable interpretation of the study results".[37] Another study linked large doses of sucralose, equivalent to 11,450 packets (136 g) per day in a person, to DNA damage in mice.[38]

See also

References

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 8854.

- ^ Anonymous. Scifinder - Substance Detail for 56038-13-2. , October 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "All About Sucralose". Calorie Control Council.

- ^ a b c d Michael A. Friedman, Lead Deputy Commissioner for the FDA, Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Sucralose Federal Register: 21 CFR Part 172, Docket No. 87F-0086, April 3, 1998

- ^ A Report on Sucralose from the Food Sanitation Council, The Japan Food Chemical Research Foundation

- ^ Gratzer, Walter (28 November 2002). "5. Light on sweetness: the discovery of aspartame". Eurekas and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-19-280403-7. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Tate & Lyle loses sucralose patent case". ap-foodtechnology.com.

- ^ "Strong Clinical Database that Supports Safety of Splenda Sweetener Products". McNeil Nutritionals, LLC. Retrieved 2009-12-30.[dead link]

- ^ Turner, James (April 3, 2006). "FDA amends regulations that include sucralose as a non-nutritive sweetener in food" (PDF). FDA Consumer. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ Tate & Lyle Sucralose Production Facility Jurong Island, Singapore

- ^ U.S. patent 5,498,709

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (2006). "Food labeling: health claims; dietary noncariogenic carbohydrate sweeteners and dental caries". Federal Register. 71 (60): 15559–15564. PMID 16572525.

- ^ Grotz, VL; Henry, RR; McGill, JB; Prince, MJ; Shamoon, H; Trout, JR; Pi-Sunyer, FX (2003). "Lack of effect of sucralose on glucose homeostasis in subjects with type 2 diabetes". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 103 (12): 1607–12. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2003.09.021. PMID 14647086.

- ^ FAP 7A3987, August 16, 1996. pp. 1–357. A 12-week study of the effect of sucralose on glucose homeostasis and HbA1c in normal healthy volunteers, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, U.S. FDA

- ^ Facts About Sucralose, American Dietetic Association, 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Ford, HE (2011 Apr). "Effects of oral ingestion of sucralose on gut hormone response and appetite in healthy normal-weight subjects". European journal of clinical nutrition. 65 (4): 508–13. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2010.291. PMID 21245879.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bannach, Gilbert (2009 Dec). "Thermal stability and thermal decomposition of sucralose". Eclética Química. 34 (4): 21–26. doi:10.1590/S0100-46702009000400002.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|pid=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sweetzfree is a clear liquid syrup base, highly concentrated, and made from 100% pure sucralose in a purified water concentrate. http://www.sweetzfree.com/

- ^ Filipic, Martha Chow Line: Sucralose sweet for calorie-counters (for 10/3/04) Ohio State Human Nutrition article on sucralose

- ^ "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2011-04-01. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ "Comparison and Safety Ratings of Food Additives". Center for Science in the Public Interest.

- ^ "Nutrition Action Health Letter" (PDF). Center for Science in the Public Interest. 2008-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Which additives are safe? Which aren't?". Center for Science in the Public Interest.

- ^ "Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Diabetes (PDF). 32 (Supplement 1). Canadian Diabetes Association: S41. 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); line feed character in|title=at position 83 (help) - ^ Goldsmith LA (2000). "Acute and subchronic toxicity of sucralose". Food Chem Toxicol. 38 Suppl 2: S53–69. PMID 10882818.

- ^ "Sucralose". FDA Final Rule. United States: Food and Drug Administration.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help)[dead link] - ^ Frank, Genevieve. "Sucralose: An Overview". Penn State University.

- ^ "Toxicity of sucralose in humans: a review" (PDF). Int. J. Morphol. 27 (1): 239–244. 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Grotz VL, Munro IC (2009). "An overview of the safety of sucralose". Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 55 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.05.011. PMID 19464334.

- ^ Grice HC, Goldsmith LA (2000). "Sucralose--an overview of the toxicity data". Food Chem Toxicol. 38 (Suppl 2): S1–6. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00023-5. PMID 10882813.

- ^ a b Baird, I. M., Shephard, N. W., Merritt, R. J., & Hildick-Smith, G. (2000). "Repeated dose study of sucralose tolerance in human subjects". Food Chemical Toxicology. 38 (Supplement 2): S123–S129. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00035-1. PMID 10882825.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Labare, Michael P; Alexander, Martin (1993). "Biodegradation of sucralose in samples of natural environments". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 12 (5): 797–804. doi:10.1897/1552-8618(1993)12[797:BOSACC]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Measurements of Sucralose in the Swedish Screening Program 2007, Part I; Sucralose in surface waters and STP samples[dead link]

- ^ Sötningsmedel sprids till miljön - Naturvårdsverket[dead link]

- ^ Browning, Lynnley (2008-09-02). "New Salvo in Splenda Skirmish". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Abou-Donia, MB; El-Masry, EM; Abdel-Rahman, AA; McLendon, RE; Schiffman, SS (2008). "Splenda alters gut microflora and increases intestinal p-glycoprotein and cytochrome p-450 in male rats". J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A. 71 (21): 1415–29. doi:10.1080/15287390802328630. PMID 18800291.

- ^ Daniells, Stephen (2009-09-02). "Sucralose safety 'scientifically sound': Expert panel".

- ^ Sasaki, YF; Kawaguchi, S; Kamaya, A; Ohshita, M; Kabasawa, K; Iwama, K; Taniguchi, K; Tsuda, S (2002-08-26). "The comet assay with 8 mouse organs: results with 39 currently used food additives". Mutation research. 519 (1–2): 103–119. PMID 12160896.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help)

External links

- U.S. FDA Code of Federal Regulations Database, Sucralose Section, As Amended Aug. 12, 1999

- Material Safety Data Sheet for Sucralose

- Ferrer, Imma; Thurman, E. M. (2010). "Analysis of sucralose and other sweeteners in water and beverage samples by liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry". J Chromatog. A. 1217 (25): 4127–4134. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)