Alton B. Parker: Difference between revisions

m moving link per principle of least surprise; removing redundant "election" |

→Presidential nomination: silver |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

Parker's long service on the bench proved to be an advantage in his nomination, as he had avoided taking stands on issues that divided the party, particularly that of currency standards. Hill and other Parker supporters remained deliberately silent on their candidate's beliefs. By the time the convention cast their votes, it was clear that no candidate but Parker could unify the party, and he was selected on the first ballot.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=137}} [[Henry G. Davis]], an elderly [[West Virginia]] millionaire and former senator, was selected as the vice presidential candidate in the hope that he would partially finance Parker's campaign.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}}{{sfn|Morris|2010|p=342}} |

Parker's long service on the bench proved to be an advantage in his nomination, as he had avoided taking stands on issues that divided the party, particularly that of currency standards. Hill and other Parker supporters remained deliberately silent on their candidate's beliefs. By the time the convention cast their votes, it was clear that no candidate but Parker could unify the party, and he was selected on the first ballot.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=137}} [[Henry G. Davis]], an elderly [[West Virginia]] millionaire and former senator, was selected as the vice presidential candidate in the hope that he would partially finance Parker's campaign.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}}{{sfn|Morris|2010|p=342}} |

||

The convention was riven by debate over whether to include a [[Free silver]] plank in the campaign's platform, opposing the [[gold standard]] and allowing silver to serve as currency as well. The "free silver" movement was popular among indebted Western farmers who felt that inflation would help them repay their debts, while business interests supported the lower inflation of the gold standard. Bryan, famous for his 1896 [[Cross of Gold speech|"Cross of Gold" speech]] |

The convention was riven by debate over whether to include a [[Free silver]] plank in the campaign's platform, opposing the [[gold standard]] and allowing silver to serve as currency as well. The "free silver" movement was popular among indebted Western farmers who felt that inflation would help them repay their debts, while business interests supported the lower inflation of the gold standard. Bryan, famous for his 1896 [[Cross of Gold speech|"Cross of Gold" speech]] called for "free silver" in order to raise prices the government would mint large numbers of silver dollars, thus driving gold out of circulation and providing orinary people with the cash to pay their debts. Bryan ran on a free silver plank in 1896 and 1900, losing both times to William McKinley and the gold standard favored by "sound money" businessmen.{{sfn|Morris|2010|pp=340–41}} |

||

However, seeking to win the support of the Eastern "sound money" faction, Parker sent a telegram to the convention immediately upon hearing news of his nomination that he considered the gold standard "firmly and irrevocably established" and would decline the nomination if he could not state this in his campaign.{{sfn|Morris|2010|pp=341–42}} The telegram sparked a new debate and fresh opposition from Bryan, but the convention eventually replied to Parker that he was free to speak on the issue as he liked.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}} National support for Parker began to rise, and Roosevelt praised his opponent's telegram in private as "bold and skillful"{{sfn|Morris|2010|p=342}} and "most adroit".{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}} |

However, seeking to win the support of the Eastern "sound money" faction, Parker sent a telegram to the convention immediately upon hearing news of his nomination that he considered the gold standard "firmly and irrevocably established" and would decline the nomination if he could not state this in his campaign.{{sfn|Morris|2010|pp=341–42}} The telegram sparked a new debate and fresh opposition from Bryan, but the convention eventually replied to Parker that he was free to speak on the issue as he liked.{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}} National support for Parker began to rise, and Roosevelt praised his opponent's telegram in private as "bold and skillful"{{sfn|Morris|2010|p=342}} and "most adroit".{{sfn|Gould|1991|p=138}} |

||

Revision as of 05:30, 29 April 2013

Alton B. Parker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals | |

| In office 1898–1904 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Andrews |

| Succeeded by | Edgar M. Cullen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alton Brooks Parker May 14, 1852 Cortland, New York |

| Died | May 10, 1926 (aged 73) New York City |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Mary L. Schoonmaker Parker |

| Alma mater | Albany Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Alton Brooks Parker (May 14, 1852 – May 10, 1926) was an American judge, best known as the conservative Democrat who lost the presidential election of 1904 to incumbent Theodore Roosevelt in a landslide.

A native of upstate New York, Parker practiced law in Kingston before being appointed to the New York Supreme Court and elected to the New York Court of Appeals; he served as Chief Justice of the latter from 1898 to 1904, when he entered presidential politics. In 1904, he defeated liberal publisher William Randolph Hearst as the Democratic Party nominee for President of the United States, opposing popular incumbent Republican President Theodore Roosevelt. After a disorganized and ineffective campaign, Parker was defeated by 336 electoral votes to 140, carrying on the Solid South. He returned to practicing law.

Early life

Parker was born in Cortland, New York to John Brooks Parker, a farmer, and Harriet F. Stratton. Both of his parents were well educated and encouraged his reading from an early age. At the age of 12 or 13, Parker watched his father serve as a juror and was so fascinated by the proceedings that he resolved to become a lawyer.[1]

However, he trained initially as a teacher and taught in Binghampton. There he became engaged to Mary Louise Schoonmaker, the daughter of a man who owned property near his school. Parker married Schoonmaker in 1872 and became a clerk at Schoonmaker & Hardenburgh, a legal firm at which one of her relatives was the senior partner.[1] He then enrolled at Albany Law School. After graduating LL.B. in 1873, he practiced law in Kingston until 1878 as the senior partner of the firm Parker & Kenyon.[2][3]

Parker also became active with the Democratic Party and was an early supporter of future New York governor and US President Grover Cleveland. He served as a delegate to the 1884 Democratic National Convention, at which Cleveland was named the party's presidential nominee; Cleveland went on to narrowly defeat Republican James G. Blaine in the fall election.[2] During this time, Parker also became a protege of David B. Hill, managing Hill's 1884 gubernatorial campaign; Hill won in a landslide.[4]

Judicial career

After his election, Hill appointed Parker to fill an 1885 vacancy on the New York Supreme Court created by the death of Justice Theodore R. Westbrook.[1] In 1886, Parker was elected to his own fourteen-year term in the seat. Three years later, Parker became a trial judge when Hill appointed him to the newly formed Second Division of the Court of Appeals. In November 1897, Parker successfully ran for the post of Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, defeating Republican William James Wallace.[2]

As a judge, Parker was notable for independently researching each case that he heard. He was generally considered to be pro-labor and was an active supporter of social reform legislation. In the 1902 decision Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co, Parker found against a woman whose face had been used in advertisements without her permission, ruling that this use did not violate her common law privacy rights. The decision was unpopular in the press and led to the passage of a privacy law by the New York State Legislature the following year. In the same year, Parker upheld the death sentence given to convicted murderer Martha Place, who became the first woman to be killed by electric chair.[1]

During his time as Chief Judge, Parker and his wife sold their Kingston home and bought an estate in Esopus on the Hudson River, calling the house "Rosemount".[1] The couple had one daughter and one son, the latter of whom died young of tetanus.[2]

Presidential nomination

As the 1904 presidential election approached, the Democrats began to search for a nominee to oppose popular incumbent Republican president Theodore Roosevelt, and Parker's name arose as a possible candidate. Roosevelt's Secretary of War Elihu Root said of Parker that he "has never opened his mouth on any national question",[5] but Roosevelt feared that the man's neutrality would prove a political advantage, writing that "the neutral-tinted individual is very apt to win against the man of pronounced views and active life".[4]

The 1904 Democratic National Convention was held in July in St. Louis, Missouri, then also hosting the 1904 World's Fair and the 1904 Summer Olympics. Parker's mentor David B. Hill—having attempted and failed to capture the nomination himself at the 1892 convention—now led the campaign for his protege's nomination.[4] William Jennings Bryan, who had been nominated but defeated by William McKinley in both 1896 and 1900, was no longer considered by delegates to be a viable alternative.[6] Radicals in the party supported publisher William Randolph Hearst but lacked sufficient numbers to secure the nomination due to opposition from Bryan and the powerful Tammany Hall political machine.[7] Small clusters of delegates pledged support to other candidates, including Missouri Senator Francis Cockrell; Richard Olney, Grover Cleveland's Secretary of State; Edward C. Wall, a former Wisconsin State Representative; and George Gray, a former Senator of Delaware. Other delegates spoke of nominating Cleveland, who had already served two nonconsecutive terms, but Cleveland was no longer popular outside the party or even within it, due to his rift with Bryan.[8]

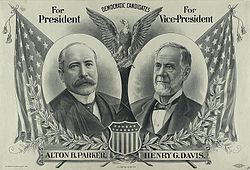

Parker's long service on the bench proved to be an advantage in his nomination, as he had avoided taking stands on issues that divided the party, particularly that of currency standards. Hill and other Parker supporters remained deliberately silent on their candidate's beliefs. By the time the convention cast their votes, it was clear that no candidate but Parker could unify the party, and he was selected on the first ballot.[8] Henry G. Davis, an elderly West Virginia millionaire and former senator, was selected as the vice presidential candidate in the hope that he would partially finance Parker's campaign.[9][10]

The convention was riven by debate over whether to include a Free silver plank in the campaign's platform, opposing the gold standard and allowing silver to serve as currency as well. The "free silver" movement was popular among indebted Western farmers who felt that inflation would help them repay their debts, while business interests supported the lower inflation of the gold standard. Bryan, famous for his 1896 "Cross of Gold" speech called for "free silver" in order to raise prices the government would mint large numbers of silver dollars, thus driving gold out of circulation and providing orinary people with the cash to pay their debts. Bryan ran on a free silver plank in 1896 and 1900, losing both times to William McKinley and the gold standard favored by "sound money" businessmen.[11]

However, seeking to win the support of the Eastern "sound money" faction, Parker sent a telegram to the convention immediately upon hearing news of his nomination that he considered the gold standard "firmly and irrevocably established" and would decline the nomination if he could not state this in his campaign.[12] The telegram sparked a new debate and fresh opposition from Bryan, but the convention eventually replied to Parker that he was free to speak on the issue as he liked.[9] National support for Parker began to rise, and Roosevelt praised his opponent's telegram in private as "bold and skillful"[10] and "most adroit".[9]

Campaign

After receiving the nomination, Parker resigned from the bench. On August 10, he was formally visited at Rosemount by a delegation of party elders to inform him of his nomination. Parker then delivered a speech criticizing Roosevelt for his administration's involvement in Turkish and Moroccan affairs and having failed to give a date on which the Philippines would become independent of American control; the speech was considered even by supporters to be impersonal and uninspiring.[13][14] Historian Lewis L. Gould described the speech as a "fiasco" for Parker from which the candidate did not recover.[15] After this initial speech, Parker retreated into a strategy of silence again, avoiding comment on all major issues.[16]

Parker's campaign soon proved to be poorly run as well.[14] Parker and his advisors opted for a front porch campaign, in which delegations would be brought to Rosemount to see Parker speak on the model of McKinley's successful 1896 campaign. However, due to Esopus' remote location and the campaign's inefficient use of funds to bring in delegates, Parker received few visitors.[14] Rather than introducing issues that would differentiate the two parties, the Democrats preferred to emphasize Roosevelt's character, portraying him as dangerously unstable.[17] Parker's campaign also failed to reach out to traditional Democratic voting blocs such as Irish Catholic immigrants.[14] In contrast, Roosevelt's campaign, headed by George Cortelyou, organized committees to appeal specifically to demographics including Jewish, black, and German-American voters.[17] John Hay, Roosevelt's Secretary of State, wrote of Parker's poor showing to Henry Adams, calling it "the most absurd political campaign of our time".[18]

A month before the election, Parker became aware of the large amount of corporate donations Cortelyou had solicited for the Roosevelt campaign, and made "Cortelyouism" a theme of his speeches, accusing the president of being insincere in previous trust busting efforts.[19] In late October, he also went on a speaking tour in the key states of New York and New Jersey, in which he reiterated the president's "shameless exhibition of a willingness to make compromise with dignity".[20] Roosevelt, enraged, released a statement calling Parker's criticisms "monstrous" and "slanderous".[21]

Parker's attacks came too late to turn the election, however. On November 8, Roosevelt won in a landslide of 7,630,457 to Parker's 5,083,880. Roosevelt carried every northern and western state, including Missouri, for a total of 336 electoral votes; Parker carried only the traditionally Democratic Solid South, accumulating 140 electoral votes.[22][3] Parker telegraphed his congratulations to Roosevelt that night and returned to private life.[23]

In Irving Stone's 1943 book They Also Ran about defeated presidential candidates, the author stated that Parker was the only defeated presidential candidate in history never to have a biography written about him. Stone theorized that Parker would have been an effective president and the 1904 election was one of a few in American history in which voters had two first-rate candidates to choose from. Stone professed that Americans liked Roosevelt more because of his colorful style.[24]

Later life

After the election, Parker resumed practicing law. He represented organized labor in several cases, most notably in Loewe v. Lawlor, popularly known as the "Danbury Hatters' case". In the case, the fur hat manufacturer D. E. Loewe & Company had attempted to enforce an open shop policy; when unions had subsequently boycotted the company, it sued the United Hatters of North America for violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The US Supreme Court found for Loewe, ruling that the union had been acting in restraint of interstate commerce. Parker served as the president of the American Bar Association from 1906 to 1907.[1]

Parker later re-entered politics, managing John A. Dix's successful 1910 gubernatorial campaign and delivering the keynote address of the 1912 Democratic National Convention, which nominated Woodrow Wilson for President.[1] In 1913, he was counsel for the managers of the trial leading to the impeachment of Dix's successor as governor, William Sulzer.[25]

Parker's wife Mary died in 1917. He remarried in 1923 to Amelia Day Campbell. On May 10, 1926, only a few days after recovering from bronchial pneumonia, Parker died from a heart attack while riding in his car through New York City's Central Park.[26] He was buried in Wiltwyck Cemetery in Kingston.[1]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robert M. Mandelbaum. "Alton Brooks Parker". New York State Unified Court System. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Appellate Division First Department: Alton B. Parker". New York State United Court System. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Alton B. Parker". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Morris 2010, p. 340.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 327.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 339.

- ^ Dalton 2002, p. 263.

- ^ a b Gould 1991, p. 137.

- ^ a b c Gould 1991, p. 138.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, p. 342.

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 340–41.

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 341–42.

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 349–50.

- ^ a b c d Gould 1991, p. 139.

- ^ Gould 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 360.

- ^ a b Gould 1991, p. 140.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 361.

- ^ Dalton 2002, p. 265.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 362.

- ^ Dalton 2002, p. 266.

- ^ Dalton 2002, p. 267.

- ^ Gould 1991, p. 143.

- ^ Stone, Irving. They Also Ran, 2nd edition. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968.

- ^

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Obituary in the New York Times on May 11, 1926 (subscription required)

Bibliography

- Dalton, Kathleen (8 October 2002). Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-679-44663-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gould, Lewis L. (1991). The presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0435-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Edmund Morris (24 November 2010). Theodore Rex. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-77781-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Cunniff, M.G. (1904). "Alton Brooks Parker: The Probable Democratic Candidate for President". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. VIII: 4923–4932. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- 1852 births

- 1926 deaths

- Albany Law School alumni

- Chief Judges of the New York Court of Appeals

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- New York Supreme Court Justices

- People from Cortland, New York

- Presidents of the American Bar Association

- Progressive Era in the United States

- United States presidential candidates, 1904